1199 BC

Antigeneia had become accustomed to acting as an equal alongside her husband Muwatalli, and so had many of the Kingdom’s great and good. However, today she acted the part of a full King in court; she sat upon the throne in the main hall, dispensing judgements and taking advice. She had taken this role a few times before, so whilst uncommon this was not a new state of affairs. But despite the power that this offered her, she did not feel fully at ease.The reason that she was acting in the kingly role in the first place was because Muwatalli and her son were both away, and she missed them both with a physical longing. She also felt pressured; she was keenly aware that some felt she was granted far too much power, that it was fundamentally foreign. Despite her previous success when called to be ‘King Antigeneia’, these whispers had never fully disappeared. The throne did not feel entirely comfortable underneath her. The hall was filled with various important persons attached to Muwatalli’s court, and sometimes it was difficult to shake the idea that all of them hated her out of her head.

She had just played arbiter in determining the boundaries of two farmsteads. A dull business but a necessary one. The temporary lull in activity afterwards, however, was ended.

“I announce, Great Queen, Woinewas of Amarendos!”

Ah yes, the most important business of the day.

Woinewas walked into the hall, carrying his helmet respectfully at his side. With him were several attendants carrying what were almost certainly chests of various kinds of tribute, which was pleasing to the eye. However, what immediately catch Antigeneia’s eye was Woinewas’ own demeanour; whilst the man could never be called craven, he was noticeably less confident in his demeanour. Given that his return seemed to herald a successful mission, this was odd.

“My King, I return from Nasoptolis and from ancient Kuwnos with tribute and with good news.”

“I am pleased to hear it Woinewas of Amarendos, tell us of your success.”

“From the King of Hounds at Kuwnos, I bring an Egyptian necklace of carnelian and gold, and a sacred rhyton from Crete in gold leaf. He has opened his city to our ships and has pledged his friendship. From the King of Summer and the King of Winter at Nasoptolis, I bring three fine horses, a panoply inlaid with gold silver and electrum, and a chest of silver. They have opened their city to our ships and pledged their friendship.”

This is good news, so why are you nervous?

“You have served your King well, Woinewas. How did you persuade these Kings to relent?”

There was a moment of uncomfortable silence, which told Antigeneia half the story by itself.

“The King of Hounds was at first... unconvinced by the idea of an alliance. But it became clear that warlords towards Theqai have been threatening the lands of Kuwnos and that he was interested in warriors. I promised him the aid of our king and our warriors should he call upon them. Did I overstep my bounds, my King?”

“You have not Woinewas, we will demonstrate our fidelity to our friends and make predators witness our might. Did you tell him how much support to expect?”

“I did, with wild exaggeration...”

The room broke out into laughter.

“And what of the Kings of Summer and Winter?”

The colour drained a little from Woinewas’ face.

“The Kings of Summer and Winter believe the Northern Abantes are aggressive pelasgoi and wish to gain allies against them. They admire our craftsmanship and our strength and wish to be aligned with it.” There was an uncomfortable pause. “And the King of Winter would not consider an alliance without a marriage being involved.”

“Very well, who is to be married?”

“I am to be married to the niece of the King of Winter.”

Frantic whispering immediately broke in the room, and expectation turned to hostility. Antigeneia wanted to leap from her seat and yell at Woinewas. He had been sent to negotiate an alliance, and instead he had married himself into a foreign dynasty of some power and no small ambition. However, this was not the time or the place for such displays, and so she calmed herself.

“May I, King in the stead of my husband, meet your bride?”

Woinewas turned and called out towards the doors of the hall. A slightly gangly form emerged from the doorway, clad in exquisite black linen and decorated in gold and lapis lazuli. As Antigeneia examined this potential viper in their midst, she noted that the girl’s clothes were a little too loose for her; the hem of her skirt was slightly lower than was usually comfortable, and quite some loose material above the waist was behind held in check with a fashionable girdle. The clothes were beautiful, but had clearly not been made for her originally. They may well have been intended for a daughter of the King of Winter who had died before she could be wed. The girl was also shaking, and unable to lift her head to meet that of Antigeneia. She was trying to steady herself, but unable to do so. And the Queen of Euboea, King in the stead of her husband, felt her heart soften towards this girl. She had lived long enough to tell the difference between feigned modesty and genuine terror. As she considered the dilemma in front of her, she felt herself attracted to the riskier option of the two she was considering. Then she thought of her husband and what he would do; that made up her mind.

“What is your name, honoured guest?”

“My n-name is Kessandara. I am daughter of Hekhanor, brother to the King of W-winter.”

“Kessandara, daughter of Hekhanor, as King and master of this house I take you under my protection. My bread and water are yours, my roof is over your head, my sworn warriors shall protect you as they protect your husband. No harm shall come to you by my hand, lest Poseidon bring down this palace around my ears and the Oath Gods carve out my heart. Woinewas of Amarendos, care for her with all of your power.”

The relief on Woinewas’ face was palpable.

“I swear it, my King. A dowry was given to me by the King of Winter of gold and silver; I offer it to you first.”

“Set aside a seventh for sacred Teleia, and take the rest for yourself as your rightful possession. A feast will be held for this occasion, so I ask that you and Kessandara both stay with us for the night.”

“Of course, my king.”

“You have created powerful alliances for us, this will not be forgotten. Go in peace, lord of Amarendos and daughter of Hekhanor.”

As Woinewas and his retainers passed out of the hall again, conversation erupted between those present. As Antigeneia relaxed a little on the throne, the elderly Ortinawos came up beside the throne.

“My king, forgive my bluntness in my old age, but does this development not trouble you? The King of Winter is older than I am, and is known for his cunning; it seems to me he means to make a mockery, or mischief, with this marriage.”

“I agree with you, Ortinawos. He definitely means to cause mischief. He means to throw a stone at a flock of chickens and see where they scatter. Would you say I am a chicken, Ortinawos?”

“No, my King. Of all animals that is one that least resembles all of your mighty qualities.”

“Well, then I will not act like a chicken. I will not flinch for this Minyan king’s amusement. My husband is not a chicken either. Abantes, and Hittites it seems to me, are made of sterner stuff than this.”

“Very well put, my King. You must agree that this is a risk, though.”

“Yes it is. I’m placing trust in kindness, and in my ability to tell a genuinely frightened girl from a lying harpy. The sure thing would be to execute them both, perhaps, or to refuse the marriage. Or would it? If a governor of our kingdom thinks that he will be executed because a foreign king demanded his betrothal, why would he ever choose to serve?”

“I agree that those are reasons to trust your instincts, but I do not believe that is why you chose to accept the marriage my King.”

Antigeneia glanced at Ortinawos; she could swear he had become much wilier as he had gotten older. And to think the Abantes tell stories about you swearing at an army of Iolkans.

“I would shoot an arrow into the heart of a bronze clad enemy, I would crush the hand of any of the men in this room if they dared raise it against my husband, I will not execute a frightened girl. The King of Winter is not here, or on this island at all, and there are no scribes on this island that I know of. If she is treated with kindness, I don’t think violence is necessary.”

“There may be rumours, my king, that this is because you seek to do another woman a favour.”

“There might be. But when my husband returns and makes exactly the same decision as me, I don’t think those rumours will have much impact.”

“For what it’s worth, I would like to add that I think you chose the right option. Particularly because the twin kings wanted to goad you or your husband into action. I am not convinced they will be faithful allies.”

“They can choose to treat an alliance with my husband as empty words. At which point, we can choose to remain safely in port whilst their city is ransacked by a warlord or a horde of pelasgoi. The choice is theirs.”

Antigeneia had become accustomed to acting as an equal alongside her husband Muwatalli, and so had many of the Kingdom’s great and good. However, today she acted the part of a full King in court; she sat upon the throne in the main hall, dispensing judgements and taking advice. She had taken this role a few times before, so whilst uncommon this was not a new state of affairs. But despite the power that this offered her, she did not feel fully at ease.The reason that she was acting in the kingly role in the first place was because Muwatalli and her son were both away, and she missed them both with a physical longing. She also felt pressured; she was keenly aware that some felt she was granted far too much power, that it was fundamentally foreign. Despite her previous success when called to be ‘King Antigeneia’, these whispers had never fully disappeared. The throne did not feel entirely comfortable underneath her. The hall was filled with various important persons attached to Muwatalli’s court, and sometimes it was difficult to shake the idea that all of them hated her out of her head.

She had just played arbiter in determining the boundaries of two farmsteads. A dull business but a necessary one. The temporary lull in activity afterwards, however, was ended.

“I announce, Great Queen, Woinewas of Amarendos!”

Ah yes, the most important business of the day.

Woinewas walked into the hall, carrying his helmet respectfully at his side. With him were several attendants carrying what were almost certainly chests of various kinds of tribute, which was pleasing to the eye. However, what immediately catch Antigeneia’s eye was Woinewas’ own demeanour; whilst the man could never be called craven, he was noticeably less confident in his demeanour. Given that his return seemed to herald a successful mission, this was odd.

“My King, I return from Nasoptolis and from ancient Kuwnos with tribute and with good news.”

“I am pleased to hear it Woinewas of Amarendos, tell us of your success.”

“From the King of Hounds at Kuwnos, I bring an Egyptian necklace of carnelian and gold, and a sacred rhyton from Crete in gold leaf. He has opened his city to our ships and has pledged his friendship. From the King of Summer and the King of Winter at Nasoptolis, I bring three fine horses, a panoply inlaid with gold silver and electrum, and a chest of silver. They have opened their city to our ships and pledged their friendship.”

This is good news, so why are you nervous?

“You have served your King well, Woinewas. How did you persuade these Kings to relent?”

There was a moment of uncomfortable silence, which told Antigeneia half the story by itself.

“The King of Hounds was at first... unconvinced by the idea of an alliance. But it became clear that warlords towards Theqai have been threatening the lands of Kuwnos and that he was interested in warriors. I promised him the aid of our king and our warriors should he call upon them. Did I overstep my bounds, my King?”

“You have not Woinewas, we will demonstrate our fidelity to our friends and make predators witness our might. Did you tell him how much support to expect?”

“I did, with wild exaggeration...”

The room broke out into laughter.

“And what of the Kings of Summer and Winter?”

The colour drained a little from Woinewas’ face.

“The Kings of Summer and Winter believe the Northern Abantes are aggressive pelasgoi and wish to gain allies against them. They admire our craftsmanship and our strength and wish to be aligned with it.” There was an uncomfortable pause. “And the King of Winter would not consider an alliance without a marriage being involved.”

“Very well, who is to be married?”

“I am to be married to the niece of the King of Winter.”

Frantic whispering immediately broke in the room, and expectation turned to hostility. Antigeneia wanted to leap from her seat and yell at Woinewas. He had been sent to negotiate an alliance, and instead he had married himself into a foreign dynasty of some power and no small ambition. However, this was not the time or the place for such displays, and so she calmed herself.

“May I, King in the stead of my husband, meet your bride?”

Woinewas turned and called out towards the doors of the hall. A slightly gangly form emerged from the doorway, clad in exquisite black linen and decorated in gold and lapis lazuli. As Antigeneia examined this potential viper in their midst, she noted that the girl’s clothes were a little too loose for her; the hem of her skirt was slightly lower than was usually comfortable, and quite some loose material above the waist was behind held in check with a fashionable girdle. The clothes were beautiful, but had clearly not been made for her originally. They may well have been intended for a daughter of the King of Winter who had died before she could be wed. The girl was also shaking, and unable to lift her head to meet that of Antigeneia. She was trying to steady herself, but unable to do so. And the Queen of Euboea, King in the stead of her husband, felt her heart soften towards this girl. She had lived long enough to tell the difference between feigned modesty and genuine terror. As she considered the dilemma in front of her, she felt herself attracted to the riskier option of the two she was considering. Then she thought of her husband and what he would do; that made up her mind.

“What is your name, honoured guest?”

“My n-name is Kessandara. I am daughter of Hekhanor, brother to the King of W-winter.”

“Kessandara, daughter of Hekhanor, as King and master of this house I take you under my protection. My bread and water are yours, my roof is over your head, my sworn warriors shall protect you as they protect your husband. No harm shall come to you by my hand, lest Poseidon bring down this palace around my ears and the Oath Gods carve out my heart. Woinewas of Amarendos, care for her with all of your power.”

The relief on Woinewas’ face was palpable.

“I swear it, my King. A dowry was given to me by the King of Winter of gold and silver; I offer it to you first.”

“Set aside a seventh for sacred Teleia, and take the rest for yourself as your rightful possession. A feast will be held for this occasion, so I ask that you and Kessandara both stay with us for the night.”

“Of course, my king.”

“You have created powerful alliances for us, this will not be forgotten. Go in peace, lord of Amarendos and daughter of Hekhanor.”

As Woinewas and his retainers passed out of the hall again, conversation erupted between those present. As Antigeneia relaxed a little on the throne, the elderly Ortinawos came up beside the throne.

“My king, forgive my bluntness in my old age, but does this development not trouble you? The King of Winter is older than I am, and is known for his cunning; it seems to me he means to make a mockery, or mischief, with this marriage.”

“I agree with you, Ortinawos. He definitely means to cause mischief. He means to throw a stone at a flock of chickens and see where they scatter. Would you say I am a chicken, Ortinawos?”

“No, my King. Of all animals that is one that least resembles all of your mighty qualities.”

“Well, then I will not act like a chicken. I will not flinch for this Minyan king’s amusement. My husband is not a chicken either. Abantes, and Hittites it seems to me, are made of sterner stuff than this.”

“Very well put, my King. You must agree that this is a risk, though.”

“Yes it is. I’m placing trust in kindness, and in my ability to tell a genuinely frightened girl from a lying harpy. The sure thing would be to execute them both, perhaps, or to refuse the marriage. Or would it? If a governor of our kingdom thinks that he will be executed because a foreign king demanded his betrothal, why would he ever choose to serve?”

“I agree that those are reasons to trust your instincts, but I do not believe that is why you chose to accept the marriage my King.”

Antigeneia glanced at Ortinawos; she could swear he had become much wilier as he had gotten older. And to think the Abantes tell stories about you swearing at an army of Iolkans.

“I would shoot an arrow into the heart of a bronze clad enemy, I would crush the hand of any of the men in this room if they dared raise it against my husband, I will not execute a frightened girl. The King of Winter is not here, or on this island at all, and there are no scribes on this island that I know of. If she is treated with kindness, I don’t think violence is necessary.”

“There may be rumours, my king, that this is because you seek to do another woman a favour.”

“There might be. But when my husband returns and makes exactly the same decision as me, I don’t think those rumours will have much impact.”

“For what it’s worth, I would like to add that I think you chose the right option. Particularly because the twin kings wanted to goad you or your husband into action. I am not convinced they will be faithful allies.”

“They can choose to treat an alliance with my husband as empty words. At which point, we can choose to remain safely in port whilst their city is ransacked by a warlord or a horde of pelasgoi. The choice is theirs.”

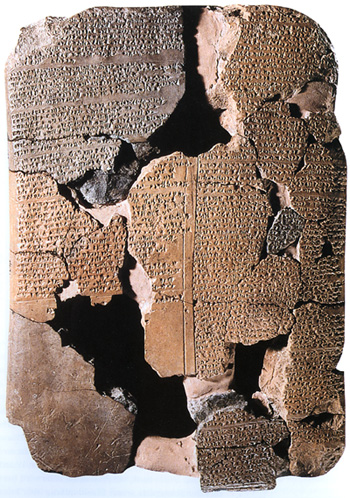

This scene is contained within a shenu, an Egyptian symbol found in a variety of contexts which all relate to eternal protection. The word itself means 'encircle'. The scene itself is of the appearance of the sun, at the birth of the world; here the sun is an infant, on a lilypad. Carnelians were one of the principle semi precious stones associated with Egyptian jewellry, despite being fairly common within Egypt itself; the stone was associated with both the sun and with the red eye of Horus.