This entry is probably going to be the most error-riddled so far; I'm simply not an expert on 1840s military tactics. For that reason, I've tried to paint the battles with as broad strokes as possible. Still, if I've made any egregious errors, please let me know. Also, I haven't included anything on the naval battles during this period; I intend to cover those during a later update. And: maps!

---------------------------------------

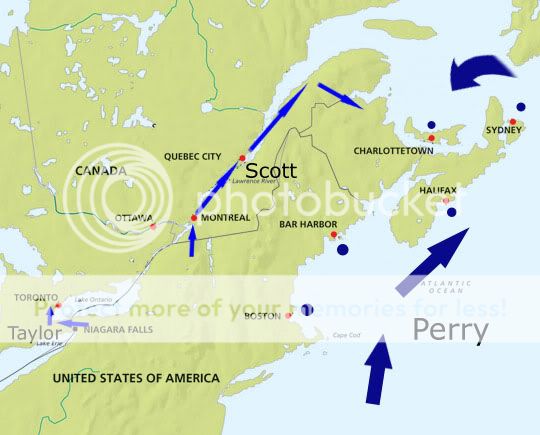

July 1848: While Taylor and Wellington are furiously preparing their respective armies, Winfield Scott, the hero of Mexico City, is returning to the United States as quickly as he can with 8000 men. Cass and Taylor are determined not to make the mistakes that doomed previous American invasions of Canada. Simple strategies, with clear goals and sufficient men to carry them out, are what will carry the day in Canada. With Scott’s army, the American force will have approximately 35,000 men under arms. Fifteen thousand under Taylor are to cross at Niagra and move northeast to capture Toronto. Twenty thousand under Scott will move north across the New York border and capture Montreal, then proceed along the St. Lawrence River to capture Quebec City and eventually secure the New Brunswick coast with the aide of Commodore Matthew Perry. Simple.

American Strategy for Canadian Invasion. Blue circles represent American naval defensive positions.

Over the next month, Scott will move his army from New Orleans up along the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers, and disembark them at Pittsburgh to march overland to northern New York.

September 1848: The British continue recruiting and training their men to cross the Atlantic and fight in Canada. FitzRoy Somerset, Baron Raglan, the military secretary of the Duke of Wellington, is appointed to the rank of General and is named commander of the British force in Canada. He, along with Wellington, hope to have at least 20,000 men ready by the end of the month.

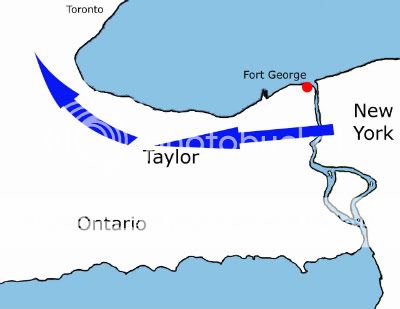

September 8, 1848: The invasion of Canada begins. Taylor’s men successfully force a crossing at the Niagra River south of Fort George. The fort has a garrison of 300 men; Taylor simply ignores it. They are met at the village of Allanburg by approximately 2000 militiamen from Niagra and the surrounding area. Shots are fired, but the militiamen quickly pull back as they realize they are massively outnumbered.

Taylor's movement through Niagra.

Canada’s military forces are commanded by General William Rowan, an able and competent leader. Scott and Taylor have their mission, and Rowan has his, which can be summed up in one word: stall. With a force of only 10,000 regulars, Rowan knows that he can’t last for long against Scott’s army. Rowan’s men are untried and supported by poorly trained militiamen. Scott, by contrast, leads a force of proven soldiers, fresh from a victory in Mexico, who have seen combat and know they can handle themselves. Rowan, therefore, recognizes he can’t hope to defeat the Americans. All he can hope to do is stall them until reinforcements from Britain arrive.

Rowan predicts that Scott (although, of course, he doesn’t know the name of the American commander yet) will move towards Quebec City. The coast is the key to the American strategy, it is clear, and the Americans can let the interior of Canada handle itself. Therefore, Rowan moves his men towards Quebec City, to intercept the Americans, on September 1.

On September 2, a British cavalry scout near Plattsburgh, NY spots a mass of smoke to the southwest--Scott’s army, assembling. The scout rides like a madman back to report to Rowan, who is startled to realize that Scott is not where he should be. In an act of snap leadership, Rowan manages to march his army of approximately 10,000 regulars and 5,000 militia the 160 miles to Montreal in just five days, arriving there on Sept. 8.

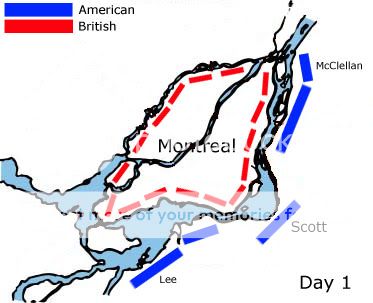

September 10, 1848: Scott’s invasion of Canada has gone well. Crossing over the border north of Plattsburgh, he has encountered little resistance--some militiamen, but nothing his troops can’t handle. Stores are plentiful; the Canadians have had a bountiful harvest. On the morning of Sept. 10, he spurs his horse and crests a small rise to see the picturesque panorama of Montreal spread out before him, still sleepy in the early morning, and commands his men to advance. After that, nothing goes right.

Rowan and his men have arrived two days prior, and spent those two days hard at work fortifying positions around the city. As Scott’s men advance, Rowan’s small accompaniment of artillery fires, signaling a general volley from Rowan’s musket-men behind earthen berms.

Battle of Montreal, Day One

Scott, whose men are hideously exposed on the plain around Montreal, orders a charge from his cavalry under Col. Albert Sidney Johnston. Although Johnston’s men succeed in getting in among the British in the frontline fortifications, they are unable to capitalize on this breach, and are forced back. Scott’s infantrymen, without cover and subject to withering fire, are even less successful. Scott orders a temporary withdrawal.

While Scott’s aide-de-camp, Maj. Thomas Jackson, suggests simply bypassing Montreal, Scott won’t hear of it. Not only is the capture of Montreal vital to America’s war plans, he cannot leave a substantial enemy force at his back. Montreal must be taken.

September 13, 1848: Although it has been slower than he had hoped, Taylor is satisfied with his progress. He now sits on the outskirts of Toronto, which seems to have only minimal defenses. He intends to let his men have a day of rest before continuing the assault, to ensure they are fit and ready.

Scott, meanwhile, is in hell. For the past two days, he has been engaged in an artillery bombardment of the British positions, pouring cannonballs by the dozen down on Rowan’s men, with very little to show for it. Time is running out. He must be at the mouth of the St. Lawrence Seaway by the middle of October to link up with Commodore Perry. That is now only a month away.

September 14, 1848: Battle of Toronto: Taylor’s troops fight 3000 militia with minimal casualties. The militia commander surrenders after just three hours, and Taylor is jovial as he accepts the other man’s sword. Indeed, to the Canadian militia, this battle, even though they have lost, seems a grand adventure.

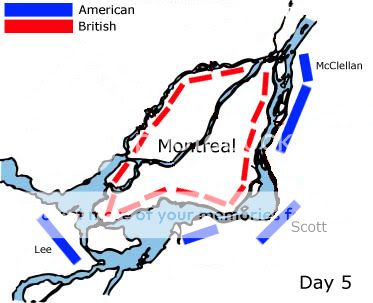

Battle of Montreal, day 5: Scott, having reduced the British defenses at Verdun and Lasalle to heaps of loose dirt, orders his men to attack across the St. Lawrence River. This attack is rebuffed, but at high casualties to the British.

Battle of Montreal, Day Five

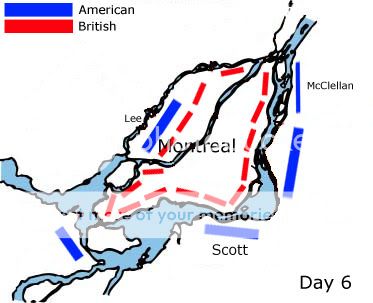

September 15, 1848: Battle of Montreal, day 6: Lt. Col. Robert E. Lee proposes to General Scott a night-time attack, under cover of darkness, near Ile Bizard. After some thought, Scott approves. Although the Americans take tremendous losses, by morning a beachhead has been forced on the northeast side of the Ile de Montreal.

Battle of Montreal, Day Six

September 16, 1848: Battle of Montreal, day 7: House-to-house fighting in Ste. Genevieve and Dollard des Ormeaux. The Americans prove to be good at this; the Mexican veterans being particularly vicious.

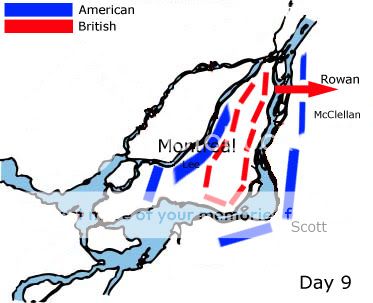

September 18, 1848: Battle of Montreal, day 9: American troops reach Outremont. Recognizing the situation is lost, Rowan and his troops withdraw to the east, fighting their way through Maj. George McClellan’s troops, despite Scott’s explicit orders to McClellan not to allow them to escape. Rowan has lost nearly 3000 men; the Americans, 7500.

Battle of Montreal, Day Nine

September 19 - 26, 1848: Rowan’s troops engage in retreat to Quebec City. Scott attempts to pursue, but is hampered by the arrival of 3,000 militiamen from New Brunswick. Untried, ill-equipped, and badly trained, the militiamen are cut down wholesale by the Americans, but they manage, through dint of sheer courage, to slow the Americans down for a day. That day proves crucial, as it allows Rowan to escape to Quebec City and begin the process of fortifying that city.

Scott is joined by half of Taylor’s army, the remainder having stayed in Toronto for occupation. Bolstered by this increase in numbers, Scott moves at full speed toward Quebec City.

September 28, 1848: Battle of Quebec, day -1: Determined not to make the same mistake twice, Scott immediately dispatches cavalry to scout the full extent of the British fortifications. Any weakness will be exploited. The cavalry, under the command of Albert Johnston, report that the fortifications are far less formidable than those of Montreal. In addition, Quebec is not on an island, which makes assaulting its defenses that much easier. Satisfied with this intelligence, Scott begins drawing up his order of battle. Tomorrow will see a full-fledged attack on the whole of the British defenses.

Writing to his wife, Mary, Lt. Col. Robert E. Lee muses on the possibility of his own death in the forthcoming battle. “I have feared death nowhere, not in Mexico, nor in Texas, or in Montreal, and I do not fear it tomorrow. But I have seen these British in the sting and clash of battle, and though they are outnumbered, outgunned, outsoldiered, I do think they shall fight like lions, for they fought like lions at Montreal. Therefore, it is likely that I may die. Oh Mary, how I long to see you! But my ties of loyalty to this country are undiminished, are as undiminishing as my ties to you, and I can think of no glorious cause to die in the service of than that of this great nation. I shall go into battle tomorrow with a light heart, knowing that we may yet win, with God on our side. And we must win. If we do not win, here and now, then this war shall not be won for ten years.” His words would prove prescient.

September 29, 1848: Battle of Quebec, day 1: “The Day of Reckoning.” So writes Col. Joseph Hooker in his diary, and he is correct. Cold weather is already beginning to move in; within a few weeks, it will be below freezing. By that time, the American army must be at the New Brunswick coast, to prevent the landing of any British troops.

The battle begins at dawn, with a cannon volley designed to demoralize the defending British. It does not work. The British remain steadfast at their defenses. Despite this minor setback, the situation favors the Americans. Their morale is high, having won two victories at Toronto and at Montreal. Quebec is not as easily defensible as Montreal, and the British have had less time to prepare defenses. The American forces number around 19,000 men, the British just 7000 regulars, plus 4000 militia. Rowan needs to hold out for several days, while Scott needs a quick victory in a day or less. Neither man will get their wish.

Although the British defenses are weak, they nonetheless provide enough of a challenge to prevent Johnston and McClellan’s cavalry from getting a toehold inside the British line of battle. It is Robert E. Lee, the recently promoted young colonel from Virginia, who proves most valuable. His regiment successfully crosses the St. Lawrence at Saint Croix, a risky maneuver, since he might be cut off by the British. Instead, he forces a small contingent of roughly 1000 Canadian militia men to retreat through Pont Rouge, thus creating an American beachhead on the north side of the city and preparing the way for an American encirclement. The day ends with much movement but little actual gain by either side.

September 30, 1848: Battle of Quebec, day 2: With a beachhead on the north bank of the St. Lawrence, Scott elects to encircle the British and compel surrender. Rowan, recognizing the danger to his own forces, attempts to contest this, resulting in bloody fighting all through the small villages of Lac-Saint-Charles, Saint-Emile, and Loretteville. Losses are staggering for both sides: at one point, the Americans lose 752 men in twenty minutes, British casualties, though uncounted, are thought to be worse, and eventually it is clear that the British cannot withstand a third day of this carnage.

October 1, 1848: Shortly before dawn, encircled and hemorrhaging men, William Rowan meets with Winfield Scott and surrenders his troops. “I have lost half my men and the whole of my country. I expect you think I am the greatest military fool since Croesus,” Rowan is said to have remarked upon meeting Scott. “No,” replied Scott. “Let history decide who was the fool here.”

October 6, 1848: 20,000 British troops under Lord Raglan land at Riviere-du-Loop, and establish winter quarters there. It is expected that another 20,000 will arrive before the end of the winter.

-------------------------------------------

Your thoughts?