It will become an American state in 1859, just like OTL. The Americans and French arraignment over the Southwest ends in 1856, which will be covered in a future update.Is the Oregon still a joint British-US territory at this point ?

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Californie- French California

- Thread starter The Tai-Pan

- Start date

Is the Oregon still a joint British-US territory at this point ?

America ITTL doesn't have the deep water pacific ports in Los Angeles, San Diego, and San Fransisco, the demand for having a port along the Puget Sound is so much stronger ITTL. Sure the British and the French might like the idea of preventing the Yankees from getting a pacific port to keep the transpacific trade for themselves, but neither have the willpower or the strength to actually fight a war over it, so it's basically assured they would capitulate here as they did OTL.

Considering the settlement of Californie by Americans is at least somewhat stymied, it's likely the PNW ITTL has received a greater number of immigrants and infrastructure than it did at this point OTL. Especially so now that the peak of the gold rush is over. I imagine that instead of going from Iowa to San Francisco, the Americans will probably build the first transcontinental line to go from Minnesota to Seattle, which has all sort of potential downstream effects for the settlement of the west and relationship with the Sioux.

Mix of French, Mexican spanish and american englishI wonder how would Californien French develop as a dialect.

I wonder how would Californien French develop as a dialect.

I would bet it would vary depending on what part of Californien you are currently in. If in the Northeast with all the Mormons, you'll see mostly English, but with a few french loan words early on; but as the territory develops and becomes more interconnected, I'd bet French would become more prevalent, but since it is a border region, English would still remain supreme. In the Southern regions French with heavy Mexican Spanish dialect. Coastal Western and Northern Regions are likely to be mostly French.Mix of French, Mexican spanish and american english

You'd hear quite a riot of languages in the goldfields. French and English would be the biggest, but you'd also hear Gaelic, dialects of Chinese, Spanish (both New World and Old), Portuguese, Russian and a whole raft of native American tongues. Although this won't last, it is important to keep in mind just how crazy diverse those early years are.I would bet it would vary depending on what part of Californien you are currently in. If in the Northeast with all the Mormons, you'll see mostly English, but with a few french loan words early on; but as the territory develops and becomes more interconnected, I'd bet French would become more prevalent, but since it is a border region, English would still remain supreme. In the Southern regions French with heavy Mexican Spanish dialect. Coastal Western and Northern Regions are likely to be mostly French.

I can see English being the unofficial second language, like Spanish in OTL America.

Post #20- L'Arrière-pays

Post #20- The Frontier

Mountains are the beginning and the end of all natural scenery.

John Ruskin

The main areas of European settlement in Californie midway through the nineteenth century could be divided into three major zones. First were the old Spanish and Mexican era communities dating back before the French conquest, generally concentrated in the south. These were made up of the coastal towns, such as Los Angeles, San Diego and Santa Barbara along with a sprinkling of landed estates and old missions in the dry interior. Second were the slightly more Frenchified northern areas about Monte Rey and the still tiny pre-Rush San Francisco.

The rest of the colony, all of the varied arid deserts, snowy mountains, high steppes all fell into the last category. Called the l'arrière-pays (back country) by the French, this vast region was an incredibly diverse region, covering landscapes ranging from the coastal rainforests of the north to the blistering salt wastes of the south. While very thinly populated by Europeans, these expanses were populated by hundreds of diverse Native Americans tribes, many of which were still living their traditional lifestyles, only slightly impacted by the arrival of white settlement.

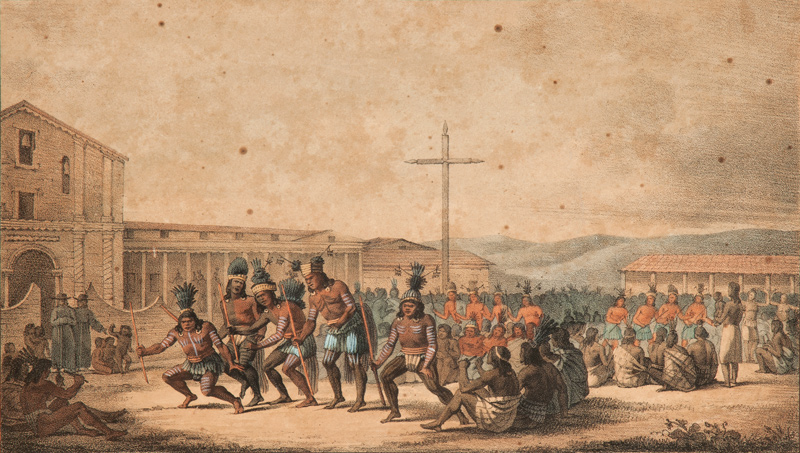

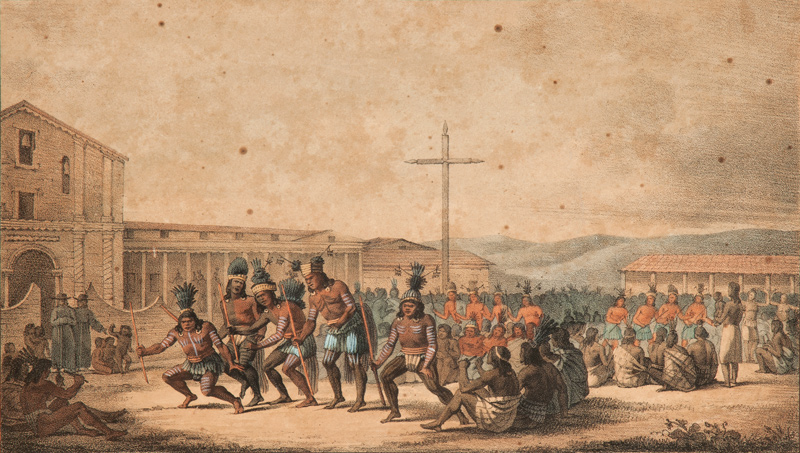

Native American tribes living as they had done for thousands of years

White penetration of the interior dated much farther back than the French annexation of Californie in 1836, of course. Explorers, trappers and traders had been entering the Rocky Mountain region for decades, following the ancient Native American paths forged for the same purposes. The most famous of these were, of course, the Mountain Men. Generally Americans, they were rugged loners who set off into as yet unexplored (by whites) territory, generally as part of the lucrative fur market. For decades these rough frontiersmen roamed the Rocky Mountain region, generally ignoring the shifting national boundaries and agreements in search of valuable beaver pelts. Transient, cosmopolitan and often iconoclastic, these men mingled freely with both the rugged natural landscape around them and the native tribes filling it. Indeed, many of these trappers came to rely on local guides and experts, sometimes even marrying them. Despite finding or even building many of the trails and passes later settlers would use, the fur trade had been in steep decline for years and by the time of French conquest was quickly vanishing. Still, for many years, it was the former Mountain Men who made up the bulk of mule drivers, trail guides and Indian Agents in the l'arrière-pays.

A second group, less regarded but probably more impactful on the land, were the old Catholic missions that dotted the landscape. Established by Francsians the oldest dated back to 1769 and more added through the year until the total stood slightly more than two dozen. Their goal was straight forward, to create oases of European civilization among the vast empty areas of Californie and to help bring Christianity to the native peoples. In the first respect, they generally succeeded. In many places the missions were large and imposing local centers, often consisting of not just churches and schools but workshops, farms and ranches. Local native tribes were compelled to live near them and provide forced labor for the various mission projects and enterprises. Conditions were often terrible in the missions with illnesses running rampant and cruel treatment of the natives common. Children were commonly taken away from their parents at a young age and secluded in Monjeríos (essentially nunneries) where they were converted to Christianity and forced to follow European cultural customs. With little resort Native peoples chafed under these harsh strictures, often either running away or staging revolts. Disliked by both the Europeans settlers (who jealously wished for the land held by the churches), soldiers (who hated guarding the despised organizations) and authorities (who had little control over them) the missions had largely been secularized by Mexico by 1836. Still however some lingered on in various ways as landlords, estate managers or even still operating under old rules and ignoring secularization entirely. The French finally put an end to them, closing the missions and giving the land out to farmers, former soldiers and even native tribes in some cases. By the time of the gold rush in 1850, the missions were only a bad memory.

Locals were keen to combine new faiths and old traditions, even under the watchful eye of Mission priests.

As the Mountain men and missionaries faded away, they were replaced by a menagerie of newcomers with the arrival of the French. Farmers and administrators, soldiers and traders, land speculators and naturalists, outlaws and lawmen, all could be found rubbing elbows in the mountains. They reached out to nearly every corner of the territory, blazing new trails to places where few white settlers had gone before. Small communities, trading posts and forts took root throughout the North American West, forming at strategic locations, such as river fords, crossroad junctions and mountain passes. From these tiny, irregular seeds, isolated farmsteads radiated.

Life in these early frontier settlements was often punishingly primitive. A makeshift log cabin was considered the height of luxury and living in literal caves was not unheard of. In the sequoia forests of the high Sierra Nevada, one rancher lived in a fallen log for a decade. Communications were equally crude, at best a rough dirt track through the wilderness. It was not uncommon for areas to be cut off for long periods due to impassable roads. Food was monotonous at best, consisting only of what the locals could hack out of the soil or trade locally, with starvation being a constant threat that claimed many would-be homesteads.

These hardy frontiersmen (and they were nearly all men) lived in a world dominated by nature. Extreme weather took all forms, from week-long blizzards in the mountains to sandstorms in the arid south. Droughts, floods, lighting strikes and landslides were all common occurrences. The wildlife held dangers as well, with the forests home to grizzly bears, mountain lions and rattlesnakes. More prosaically illness claimed many lives, with such ailments as cholera and typhus being particularly deadly, along with the indigenous Rocky Mountain Spotted fever. With no idea these diseases were spread by germs, settlers continued to use toxic water sources fouled by others, particularly in the winter or in crowded conditions near forts.

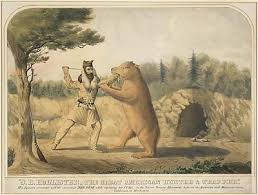

A very rare occurrence, as indicated by the poorly drawn animal.

One common survival tactic was to rely on the local Native Americans for assistance. Such people could make good neighbors and valuable trading partners if peaceable relations could be established. In fact, many settlers came to rely on such partnerships, with the locals providing information, guidance and even supplies to the settlers. Such relationships could go much deeper, with real friendships or martial connections. Native American women could be the ultimate prize for isolated European settlers. Not only did such companionship alleviate the physical loneliness, but it could also allow them to tap into a wider network of indigenous culture, providing any number of benefits. In such a stark struggle for survival, there was frequently strength in community.

So why did these men endure such brutal surroundings? Why venture into such wild and disconnected places, far from the comforts of home? For some, of course, the answer was obvious. The soldiers, Indian agents and surveyors had no choice, they had been ordered to the backcountry by a government eager to exploit it. For them, the time in the wild was akin to an exile, a time to endure. Others headed into the frontier to make money, following the markets to wherever they lead, looking forward to returning to the coast laden with wealth. Yet others were on the run, escaping failed relationships, piled debts or legal difficulties. While few were outright criminals, despite the legends, the mountains did offer a tempting place to remake one’s life.

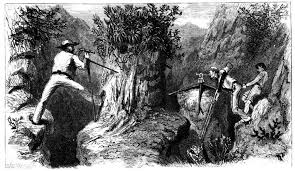

The over-looked land surveyor

For some though, the isolation and freedom was an incentive. The frontier was a land generally devoid of tax collectors, neighbors and regulations. In a time where hierarchies (political, religious, economic) dominated mainstream life, the frontier could be a tempting alternative to such strictures. Far beyond the eyes and attention of society people could live as they wanted, without the burden of responsibilities and expectations. The same inhospitable landscapes could also be a draw, with the majestic and sweeping backdrop stirring the soul. While hard to quantify, it is clear many felt attracted to these wild and seemingly unspoiled locations, nestled in picturesque locations. For people raised in the rolling hills or coasts of France, the imposing Rockies offered a striking and dramatic panorama.

However, the Gold Rush would change everything. Instead of Californie being a sleepy backwater that only sent out the occasional hardy settler, explorer or traveler, soon the explosive goldfields would be sending hordes of men into even the most remote regions. Men who had no regard for wilderness and beauty, those who only saw the towering mountains and rivers as the means to an end, as resources to be plundered.

The age of the prospector had arrived.

Mountains are the beginning and the end of all natural scenery.

John Ruskin

The main areas of European settlement in Californie midway through the nineteenth century could be divided into three major zones. First were the old Spanish and Mexican era communities dating back before the French conquest, generally concentrated in the south. These were made up of the coastal towns, such as Los Angeles, San Diego and Santa Barbara along with a sprinkling of landed estates and old missions in the dry interior. Second were the slightly more Frenchified northern areas about Monte Rey and the still tiny pre-Rush San Francisco.

The rest of the colony, all of the varied arid deserts, snowy mountains, high steppes all fell into the last category. Called the l'arrière-pays (back country) by the French, this vast region was an incredibly diverse region, covering landscapes ranging from the coastal rainforests of the north to the blistering salt wastes of the south. While very thinly populated by Europeans, these expanses were populated by hundreds of diverse Native Americans tribes, many of which were still living their traditional lifestyles, only slightly impacted by the arrival of white settlement.

Native American tribes living as they had done for thousands of years

White penetration of the interior dated much farther back than the French annexation of Californie in 1836, of course. Explorers, trappers and traders had been entering the Rocky Mountain region for decades, following the ancient Native American paths forged for the same purposes. The most famous of these were, of course, the Mountain Men. Generally Americans, they were rugged loners who set off into as yet unexplored (by whites) territory, generally as part of the lucrative fur market. For decades these rough frontiersmen roamed the Rocky Mountain region, generally ignoring the shifting national boundaries and agreements in search of valuable beaver pelts. Transient, cosmopolitan and often iconoclastic, these men mingled freely with both the rugged natural landscape around them and the native tribes filling it. Indeed, many of these trappers came to rely on local guides and experts, sometimes even marrying them. Despite finding or even building many of the trails and passes later settlers would use, the fur trade had been in steep decline for years and by the time of French conquest was quickly vanishing. Still, for many years, it was the former Mountain Men who made up the bulk of mule drivers, trail guides and Indian Agents in the l'arrière-pays.

A second group, less regarded but probably more impactful on the land, were the old Catholic missions that dotted the landscape. Established by Francsians the oldest dated back to 1769 and more added through the year until the total stood slightly more than two dozen. Their goal was straight forward, to create oases of European civilization among the vast empty areas of Californie and to help bring Christianity to the native peoples. In the first respect, they generally succeeded. In many places the missions were large and imposing local centers, often consisting of not just churches and schools but workshops, farms and ranches. Local native tribes were compelled to live near them and provide forced labor for the various mission projects and enterprises. Conditions were often terrible in the missions with illnesses running rampant and cruel treatment of the natives common. Children were commonly taken away from their parents at a young age and secluded in Monjeríos (essentially nunneries) where they were converted to Christianity and forced to follow European cultural customs. With little resort Native peoples chafed under these harsh strictures, often either running away or staging revolts. Disliked by both the Europeans settlers (who jealously wished for the land held by the churches), soldiers (who hated guarding the despised organizations) and authorities (who had little control over them) the missions had largely been secularized by Mexico by 1836. Still however some lingered on in various ways as landlords, estate managers or even still operating under old rules and ignoring secularization entirely. The French finally put an end to them, closing the missions and giving the land out to farmers, former soldiers and even native tribes in some cases. By the time of the gold rush in 1850, the missions were only a bad memory.

Locals were keen to combine new faiths and old traditions, even under the watchful eye of Mission priests.

As the Mountain men and missionaries faded away, they were replaced by a menagerie of newcomers with the arrival of the French. Farmers and administrators, soldiers and traders, land speculators and naturalists, outlaws and lawmen, all could be found rubbing elbows in the mountains. They reached out to nearly every corner of the territory, blazing new trails to places where few white settlers had gone before. Small communities, trading posts and forts took root throughout the North American West, forming at strategic locations, such as river fords, crossroad junctions and mountain passes. From these tiny, irregular seeds, isolated farmsteads radiated.

Life in these early frontier settlements was often punishingly primitive. A makeshift log cabin was considered the height of luxury and living in literal caves was not unheard of. In the sequoia forests of the high Sierra Nevada, one rancher lived in a fallen log for a decade. Communications were equally crude, at best a rough dirt track through the wilderness. It was not uncommon for areas to be cut off for long periods due to impassable roads. Food was monotonous at best, consisting only of what the locals could hack out of the soil or trade locally, with starvation being a constant threat that claimed many would-be homesteads.

These hardy frontiersmen (and they were nearly all men) lived in a world dominated by nature. Extreme weather took all forms, from week-long blizzards in the mountains to sandstorms in the arid south. Droughts, floods, lighting strikes and landslides were all common occurrences. The wildlife held dangers as well, with the forests home to grizzly bears, mountain lions and rattlesnakes. More prosaically illness claimed many lives, with such ailments as cholera and typhus being particularly deadly, along with the indigenous Rocky Mountain Spotted fever. With no idea these diseases were spread by germs, settlers continued to use toxic water sources fouled by others, particularly in the winter or in crowded conditions near forts.

A very rare occurrence, as indicated by the poorly drawn animal.

One common survival tactic was to rely on the local Native Americans for assistance. Such people could make good neighbors and valuable trading partners if peaceable relations could be established. In fact, many settlers came to rely on such partnerships, with the locals providing information, guidance and even supplies to the settlers. Such relationships could go much deeper, with real friendships or martial connections. Native American women could be the ultimate prize for isolated European settlers. Not only did such companionship alleviate the physical loneliness, but it could also allow them to tap into a wider network of indigenous culture, providing any number of benefits. In such a stark struggle for survival, there was frequently strength in community.

So why did these men endure such brutal surroundings? Why venture into such wild and disconnected places, far from the comforts of home? For some, of course, the answer was obvious. The soldiers, Indian agents and surveyors had no choice, they had been ordered to the backcountry by a government eager to exploit it. For them, the time in the wild was akin to an exile, a time to endure. Others headed into the frontier to make money, following the markets to wherever they lead, looking forward to returning to the coast laden with wealth. Yet others were on the run, escaping failed relationships, piled debts or legal difficulties. While few were outright criminals, despite the legends, the mountains did offer a tempting place to remake one’s life.

The over-looked land surveyor

For some though, the isolation and freedom was an incentive. The frontier was a land generally devoid of tax collectors, neighbors and regulations. In a time where hierarchies (political, religious, economic) dominated mainstream life, the frontier could be a tempting alternative to such strictures. Far beyond the eyes and attention of society people could live as they wanted, without the burden of responsibilities and expectations. The same inhospitable landscapes could also be a draw, with the majestic and sweeping backdrop stirring the soul. While hard to quantify, it is clear many felt attracted to these wild and seemingly unspoiled locations, nestled in picturesque locations. For people raised in the rolling hills or coasts of France, the imposing Rockies offered a striking and dramatic panorama.

However, the Gold Rush would change everything. Instead of Californie being a sleepy backwater that only sent out the occasional hardy settler, explorer or traveler, soon the explosive goldfields would be sending hordes of men into even the most remote regions. Men who had no regard for wilderness and beauty, those who only saw the towering mountains and rivers as the means to an end, as resources to be plundered.

The age of the prospector had arrived.

Last edited:

Thank you kindly. I have a French speaker I ask for help, I must have misreadGood to see you again, and as always, an excellent chapter.

But for arrière-pays you should add the l' (l'arrière-pays).

Otherwise, I can't wait to see what happens next.

Post #22- Mining in Californie

Post #21- Mining

“An unprofitable mine is fit only for the sepulcher of a dead mule.”

― T.A. Rickard

Even as the Argonauts rose in rebellion in 1852 and then subsided in defeat the year after, their world was already vanishing.The old Californie dream, that a man could wander up to a stream and fish out a fortune in an afternoon was becoming a fading memory. This was not due to poor French policy, feckless foreign miners or divine disfavor, whatever the varying slogans might have suggested. It was due to simple geology. The easy placer deposits, those fabled streambeds laden with gold, had been thoroughly plundered by 1853, exploited by years of tenacious Gold Rushers. It was not that Californie was out of gold, not by any means. It just meant that the rest of the mineral wealth lay deeper down, in pockets that would require more effort, and ingenuity to reach.

The first method of ‘mining’ in Californie had been the simplest. A would-be prospector would simply find flecks of gold in a streambed or tangled in the roots of overhanging plants and pick them ‘as a man would blackberries’. Even in Californie however, such a bounty was rare and most early mining used simple gold panning methods. The process was basic, where a prospector would use a pan to scoop streambed deposits and ‘wash’ it vigorously, allowing the heavier gold to sink to the bottom. A skilled miner would quickly shake out the lighter dirt and water, leaving only the valued gold flecks. While cheap, panning was back-breaking labor that limited even the most talented prospector to about a single cubic meter of gravel processed per day.

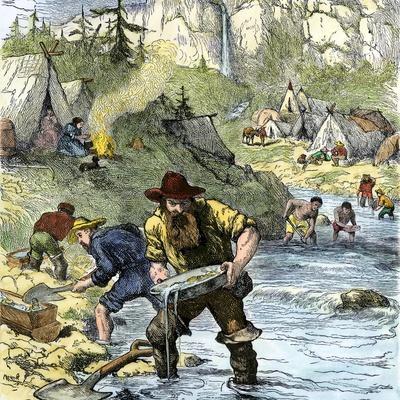

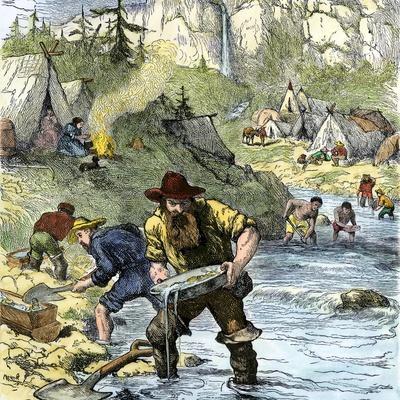

Early miners, busy at work.

A slightly more sophisticated method was using a so-called ‘rocker box’ or ‘cradle’ which was basically a larger, slightly mechanized pan, resting on rockers. The miner would pour in gravel and water, shake the entire machine, and various trays would catch the gold, while allowing the unwanted debris to flow away. While larger than a simple prospectors pan, even a rocker was usually a home-built device that could be managed by a single man, allowing a miner to triple his output, to three cubic meters a day.

It was these simple methods that characterized the initial Gold Rush boom that became globally famous. Images of grizzled men leaning over waterways, panning gold became synonymous with the Rush. Despite the romance and legends of the early goldfields and their ecosystem of ville champignon (mushroom towns) however, gold output in these early years was quite low due to these simple methods. Worse, panning and rocking were inconsistent, impossible to perform during high water floods when streams became inaccessible torrents of whitewater or were frozen solid during frigid winters. To combat these problems, and to deal with the fact of increasingly stripped streambeds, new mining techniques were needed.

The first advancement were simply larger rockers, which eventually morphed into the ‘sluice’, based on mill-races in Europe. Pioneered by French miners, the sluice took the idea of the simple panning for gold to the logical conclusion. Long troughs were made of wood, often over ten feet long, with rough bottoms (sometimes wooden ridges, sometimes simply old carpet) in the bottom to catch the heavy gold, while the water and unwanted rocks ran over. These large contraptions, which often required entire gangs of men to service them, could greatly increase the rate of gravel production. With a well made ‘Long Tom’, as the sluice boxes were nicknamed, a miner could process a cubic meter of gravel an hour, nearly ten times faster than the old prospector and his pan.

A simple drawing of a Long Tom in action, being fed by shovels of gravel

Other techniques were tried as well. Dredging, where a ship would scoop up tons of silt from river bottoms was promising but quickly faltered on poor technology. Drywashing, where air blown by bellows is used to blow off the lighter dirt was also attempted but quickly relegated only to the driest areas due to inefficiencies. In other places entire streams were diverted to erode new areas, or to expose desired gravel beds. However, the entire California mining world, and the local landscape, would be transformed by a Frenchman’s ingenious new method in 1854.

Henri-Émile Bazin was a young French engineer who, like so many miners, had avoided the entire Argonaut rebellion to focus on finding gold. Trained in hydraulics, he put his previous education to use by coming up with an entirely new way to find gold deposits. Previously miners had been forced to only explore deposits near the surface, already exposed by natural erosion. Bazin however, concluded there might be a way to expose as yet hidden gold veins, by use of pressurized water to blast away the topsoil and layers of unwanted overburden.

His first attempt involved creating a small water reservoir, and then forcing the water into ever smaller pipes, focusing the building pressure. Handling the nozzle proved difficult but Bazin came up with an elegant system of counterweights that allowed a single miner to point the gushing torrent. The rushing water could erode entire hillsides in an afternoon, washing into giant sluices built downhill from the mining site. Bazin’s invention, while primitive at first with leather hoses and wooden nozzles, was quickly adopted by many miners throughout the goldfields. The reason was obvious. A large hydraulic mining operation, supplied with adequate water, drainage and men to work the sluices, could process hundreds of cubic meters of gravel an hour, an order of magnitude more efficient than older methods.

Miners could erode away entire hills with Bazin's new methods.

Another way of accessing gold that was too deep even for Bazin’s hydraulic method was the traditional practice of sending shafts under the earth, seeking riches. Called quartz mining in Californie (due to the frequent fact that gold veins were mixed with quartz) it was the most difficult and intensive form of mining, involving considerable engineering and effort. At first it was ignored during the early Gold Rush due to seeming unnecessary. Who wanted to dig down into the earth when gold seemed so plentiful on the surface? As time went on however, and streambed deposits vanished, some started looking deeper.

One of the first was the aptly named Gold Hill, on the outskirts of the northern goldfields. First explored in 1851, it had become a flourishing gold producing site, complete with wild ville champignon. Literally millions of franc’s worth of gold was hauled out of the shallow pits and shafts dug there. By 1856 however, a more serious effort was undertaken and a systematic network of underground tunnels dug with great success. Inspired by such work, other quartz operations began forming throughout the goldfields. Many became considerable concerns hiring hundreds of miners, engineers, managers and experts. Most highly sought after in the latter category were Cornish tin miners, considered the finest underground men in the world.

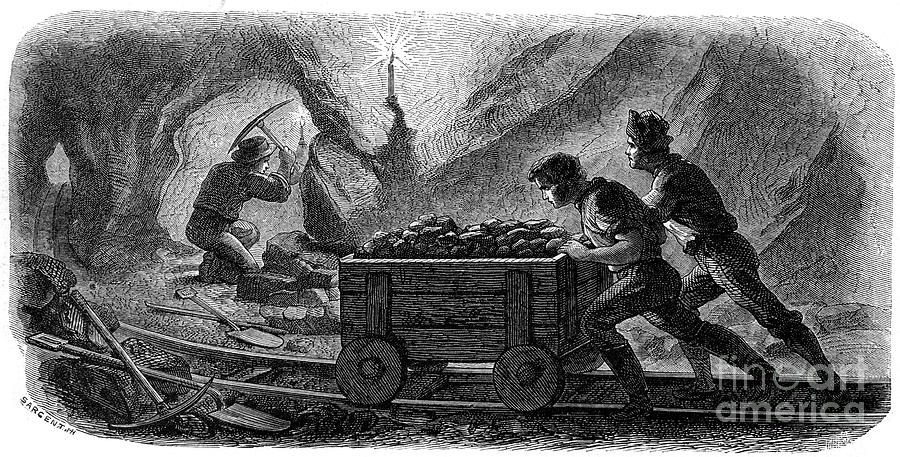

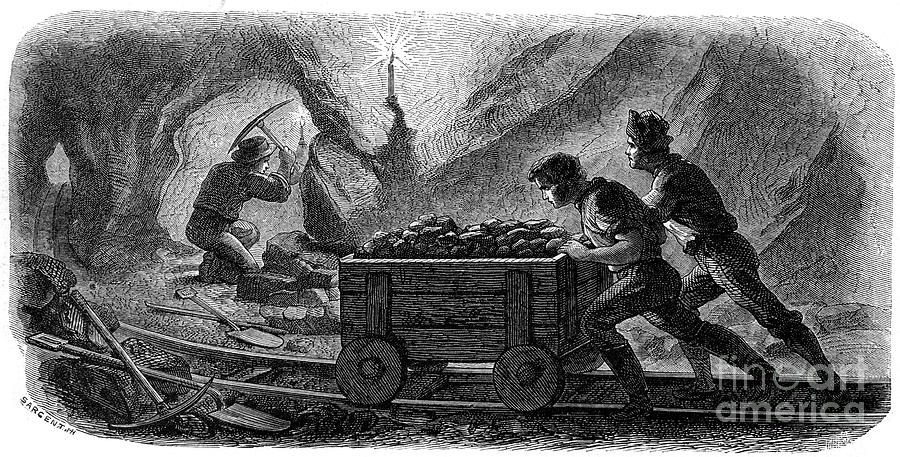

Quartz mining in action. Note the primitive lighting consisting of bare candles.

These new technologies came at a high cost of course, and not merely financial ones. As mining further industrialized, it became ever more dangerous for the workers involved. Poorly built sluices slipped and crushed, cheaply built tunnels collapsed, and men drowned in sudden floods caused by broken hydraulic dams. These brutal results of large scale industry often fell on the poorest and most desperate workers, those without skills or capital. Even more striking were the costs on the landscape. Hydraulic mining in particular was devastating on the ecosystem, consuming not only local water sources but also literally stripping away the soil, and filling every watercourse with tons of gravel and dirt. This pollution caused flooding and erosion downstream and made the water useless for any other purpose. Even quartz mining left considerable tailings and leftover piles of rock littering the landscape, much of it highly acidic.

Other changes were also visible in Californie society. As mining grew more capital intensive, it dramatically altered how the system operated. Gone were the heady days of a single miner and his shovel earning millions due to luck and hard work. Replacing it were large corporations and cartels which required considerable financial, organizational and logistical resources. The small claims that had previously dominated were soon obsoleted by gigantic operations covering many acres of ground. A single miner was transformed from his own master, into a small cog in a much larger gold generating machine. This trend was accelerated by the French authorities who much preferred working with large corporations who they could more easily assess, tax and negotiate with.

This trend marginalized many groups that had flourished during the less ordered and hierarchical periods. Women in particular were losers in this emerging new order. During the Rush they had been merchants, landlords, and in some cases miners themselves. Their skills had been in high demand in the overwhelmingly masculine world of the goldfields but as big business consolidated, they were pushed out. Companies did not hire women, and preferred to do business on a large scale with other male-oreinted enterprises.Female entrepreneurs were pushed out of business, replaced by men.

Native Americans also suffered from a similar shift in attitudes and practices. Their place during the Rush had never been very secure of course, dealing not only with racial animosity and discrimination, but outright violence. Despite intermittent French protection, almost every tribe suffered from the hordes of gold miners. Still, some had managed to hold onto claims and even become rich through mining success. Even this small consolation was swept away however, as mineral extraction became more regimented. Companies would not hire natives and their claims were bought out or taken over, with even less compensation. The newly enhanced destruction of the landscape due to hydraulic mining merely sealed the fate of the coastal Native Americans, who increasingly found fewer palatable choices.

By 1860 the old era of the Gold Rush had faded away, replaced by an increasingly centralized and French set of businesses. The wild ville champignon were slowly replaced by more organized settlements or, in some extreme cases, virtual company towns. Faced with this growing downward economic pressure many miners did the obvious and fled. Heading out for the L'Arrière-pays, these men took their considerable skills and experience out into a search for new finds, where a fortune could still be made by a single man.

Gone were the days of men at the side of a stream, replaced by engineering projects on a vast scale financed by big business.

This questing prospectors took white settlement to the remote interior of Californie, and beyond, in search of gold. Canvassing the Nouveau-Mexique and Transierra, as well as hidden pockets of Californie proper, they set off a number of miniature gold rushes in the 1860’s. Some such as the Kern Rush in 1861 and the Gloire Strike in 1865 turned out to be duds, promising sites undone by geography but others turned out to be substantial. Large finds were made both at the Gila River, near Fort Yuma and most famously in the Transierra at Virginia City, with the fabled Comstock lode. Other small finds also blossomed in this period, only lasting a short time.

All followed the same sequence of events. A small group, or even solitary prospector would find a new promising claim. Word would spread and create a stampede of other miners rushing to the side, eager to stake a claim early. Then, as the diggings started, others would follow. Traders, hustlers, prostitutes and engineers, hoping to profit from the sudden eruption of the mushroom town. For a while the place would flourish, roads built, houses erected, local government established. In some places, such as Virginia City this boom could last years, creating a new metropolis but even in small towns, the change could be dramatic. A rural gulch could host men from all over Californie, with culture, economy and politics seeming to appear out of thin air. Then the surface gold would be played out and the miners faced a stark choice. Move on to the next strike, or hold on for the next inevitable arrivals.

Then, the coastal French businessmen, or at least their agents and money. Claims would be bought up, miners hired as labor and contracts concluded with the local authorities. Real mining would start then, shafts laid deep into mountains and hills, canyons drained or depressions filled with water. The entire landscape would be transformed, just as the old Gold Rush goldfields had been. And such the miners unwilling to endure such conditions would head out, and the cycle began anew.

“An unprofitable mine is fit only for the sepulcher of a dead mule.”

― T.A. Rickard

Even as the Argonauts rose in rebellion in 1852 and then subsided in defeat the year after, their world was already vanishing.The old Californie dream, that a man could wander up to a stream and fish out a fortune in an afternoon was becoming a fading memory. This was not due to poor French policy, feckless foreign miners or divine disfavor, whatever the varying slogans might have suggested. It was due to simple geology. The easy placer deposits, those fabled streambeds laden with gold, had been thoroughly plundered by 1853, exploited by years of tenacious Gold Rushers. It was not that Californie was out of gold, not by any means. It just meant that the rest of the mineral wealth lay deeper down, in pockets that would require more effort, and ingenuity to reach.

The first method of ‘mining’ in Californie had been the simplest. A would-be prospector would simply find flecks of gold in a streambed or tangled in the roots of overhanging plants and pick them ‘as a man would blackberries’. Even in Californie however, such a bounty was rare and most early mining used simple gold panning methods. The process was basic, where a prospector would use a pan to scoop streambed deposits and ‘wash’ it vigorously, allowing the heavier gold to sink to the bottom. A skilled miner would quickly shake out the lighter dirt and water, leaving only the valued gold flecks. While cheap, panning was back-breaking labor that limited even the most talented prospector to about a single cubic meter of gravel processed per day.

Early miners, busy at work.

A slightly more sophisticated method was using a so-called ‘rocker box’ or ‘cradle’ which was basically a larger, slightly mechanized pan, resting on rockers. The miner would pour in gravel and water, shake the entire machine, and various trays would catch the gold, while allowing the unwanted debris to flow away. While larger than a simple prospectors pan, even a rocker was usually a home-built device that could be managed by a single man, allowing a miner to triple his output, to three cubic meters a day.

It was these simple methods that characterized the initial Gold Rush boom that became globally famous. Images of grizzled men leaning over waterways, panning gold became synonymous with the Rush. Despite the romance and legends of the early goldfields and their ecosystem of ville champignon (mushroom towns) however, gold output in these early years was quite low due to these simple methods. Worse, panning and rocking were inconsistent, impossible to perform during high water floods when streams became inaccessible torrents of whitewater or were frozen solid during frigid winters. To combat these problems, and to deal with the fact of increasingly stripped streambeds, new mining techniques were needed.

The first advancement were simply larger rockers, which eventually morphed into the ‘sluice’, based on mill-races in Europe. Pioneered by French miners, the sluice took the idea of the simple panning for gold to the logical conclusion. Long troughs were made of wood, often over ten feet long, with rough bottoms (sometimes wooden ridges, sometimes simply old carpet) in the bottom to catch the heavy gold, while the water and unwanted rocks ran over. These large contraptions, which often required entire gangs of men to service them, could greatly increase the rate of gravel production. With a well made ‘Long Tom’, as the sluice boxes were nicknamed, a miner could process a cubic meter of gravel an hour, nearly ten times faster than the old prospector and his pan.

A simple drawing of a Long Tom in action, being fed by shovels of gravel

Other techniques were tried as well. Dredging, where a ship would scoop up tons of silt from river bottoms was promising but quickly faltered on poor technology. Drywashing, where air blown by bellows is used to blow off the lighter dirt was also attempted but quickly relegated only to the driest areas due to inefficiencies. In other places entire streams were diverted to erode new areas, or to expose desired gravel beds. However, the entire California mining world, and the local landscape, would be transformed by a Frenchman’s ingenious new method in 1854.

Henri-Émile Bazin was a young French engineer who, like so many miners, had avoided the entire Argonaut rebellion to focus on finding gold. Trained in hydraulics, he put his previous education to use by coming up with an entirely new way to find gold deposits. Previously miners had been forced to only explore deposits near the surface, already exposed by natural erosion. Bazin however, concluded there might be a way to expose as yet hidden gold veins, by use of pressurized water to blast away the topsoil and layers of unwanted overburden.

His first attempt involved creating a small water reservoir, and then forcing the water into ever smaller pipes, focusing the building pressure. Handling the nozzle proved difficult but Bazin came up with an elegant system of counterweights that allowed a single miner to point the gushing torrent. The rushing water could erode entire hillsides in an afternoon, washing into giant sluices built downhill from the mining site. Bazin’s invention, while primitive at first with leather hoses and wooden nozzles, was quickly adopted by many miners throughout the goldfields. The reason was obvious. A large hydraulic mining operation, supplied with adequate water, drainage and men to work the sluices, could process hundreds of cubic meters of gravel an hour, an order of magnitude more efficient than older methods.

Miners could erode away entire hills with Bazin's new methods.

Another way of accessing gold that was too deep even for Bazin’s hydraulic method was the traditional practice of sending shafts under the earth, seeking riches. Called quartz mining in Californie (due to the frequent fact that gold veins were mixed with quartz) it was the most difficult and intensive form of mining, involving considerable engineering and effort. At first it was ignored during the early Gold Rush due to seeming unnecessary. Who wanted to dig down into the earth when gold seemed so plentiful on the surface? As time went on however, and streambed deposits vanished, some started looking deeper.

One of the first was the aptly named Gold Hill, on the outskirts of the northern goldfields. First explored in 1851, it had become a flourishing gold producing site, complete with wild ville champignon. Literally millions of franc’s worth of gold was hauled out of the shallow pits and shafts dug there. By 1856 however, a more serious effort was undertaken and a systematic network of underground tunnels dug with great success. Inspired by such work, other quartz operations began forming throughout the goldfields. Many became considerable concerns hiring hundreds of miners, engineers, managers and experts. Most highly sought after in the latter category were Cornish tin miners, considered the finest underground men in the world.

Quartz mining in action. Note the primitive lighting consisting of bare candles.

These new technologies came at a high cost of course, and not merely financial ones. As mining further industrialized, it became ever more dangerous for the workers involved. Poorly built sluices slipped and crushed, cheaply built tunnels collapsed, and men drowned in sudden floods caused by broken hydraulic dams. These brutal results of large scale industry often fell on the poorest and most desperate workers, those without skills or capital. Even more striking were the costs on the landscape. Hydraulic mining in particular was devastating on the ecosystem, consuming not only local water sources but also literally stripping away the soil, and filling every watercourse with tons of gravel and dirt. This pollution caused flooding and erosion downstream and made the water useless for any other purpose. Even quartz mining left considerable tailings and leftover piles of rock littering the landscape, much of it highly acidic.

Other changes were also visible in Californie society. As mining grew more capital intensive, it dramatically altered how the system operated. Gone were the heady days of a single miner and his shovel earning millions due to luck and hard work. Replacing it were large corporations and cartels which required considerable financial, organizational and logistical resources. The small claims that had previously dominated were soon obsoleted by gigantic operations covering many acres of ground. A single miner was transformed from his own master, into a small cog in a much larger gold generating machine. This trend was accelerated by the French authorities who much preferred working with large corporations who they could more easily assess, tax and negotiate with.

This trend marginalized many groups that had flourished during the less ordered and hierarchical periods. Women in particular were losers in this emerging new order. During the Rush they had been merchants, landlords, and in some cases miners themselves. Their skills had been in high demand in the overwhelmingly masculine world of the goldfields but as big business consolidated, they were pushed out. Companies did not hire women, and preferred to do business on a large scale with other male-oreinted enterprises.Female entrepreneurs were pushed out of business, replaced by men.

Native Americans also suffered from a similar shift in attitudes and practices. Their place during the Rush had never been very secure of course, dealing not only with racial animosity and discrimination, but outright violence. Despite intermittent French protection, almost every tribe suffered from the hordes of gold miners. Still, some had managed to hold onto claims and even become rich through mining success. Even this small consolation was swept away however, as mineral extraction became more regimented. Companies would not hire natives and their claims were bought out or taken over, with even less compensation. The newly enhanced destruction of the landscape due to hydraulic mining merely sealed the fate of the coastal Native Americans, who increasingly found fewer palatable choices.

By 1860 the old era of the Gold Rush had faded away, replaced by an increasingly centralized and French set of businesses. The wild ville champignon were slowly replaced by more organized settlements or, in some extreme cases, virtual company towns. Faced with this growing downward economic pressure many miners did the obvious and fled. Heading out for the L'Arrière-pays, these men took their considerable skills and experience out into a search for new finds, where a fortune could still be made by a single man.

Gone were the days of men at the side of a stream, replaced by engineering projects on a vast scale financed by big business.

This questing prospectors took white settlement to the remote interior of Californie, and beyond, in search of gold. Canvassing the Nouveau-Mexique and Transierra, as well as hidden pockets of Californie proper, they set off a number of miniature gold rushes in the 1860’s. Some such as the Kern Rush in 1861 and the Gloire Strike in 1865 turned out to be duds, promising sites undone by geography but others turned out to be substantial. Large finds were made both at the Gila River, near Fort Yuma and most famously in the Transierra at Virginia City, with the fabled Comstock lode. Other small finds also blossomed in this period, only lasting a short time.

All followed the same sequence of events. A small group, or even solitary prospector would find a new promising claim. Word would spread and create a stampede of other miners rushing to the side, eager to stake a claim early. Then, as the diggings started, others would follow. Traders, hustlers, prostitutes and engineers, hoping to profit from the sudden eruption of the mushroom town. For a while the place would flourish, roads built, houses erected, local government established. In some places, such as Virginia City this boom could last years, creating a new metropolis but even in small towns, the change could be dramatic. A rural gulch could host men from all over Californie, with culture, economy and politics seeming to appear out of thin air. Then the surface gold would be played out and the miners faced a stark choice. Move on to the next strike, or hold on for the next inevitable arrivals.

Then, the coastal French businessmen, or at least their agents and money. Claims would be bought up, miners hired as labor and contracts concluded with the local authorities. Real mining would start then, shafts laid deep into mountains and hills, canyons drained or depressions filled with water. The entire landscape would be transformed, just as the old Gold Rush goldfields had been. And such the miners unwilling to endure such conditions would head out, and the cycle began anew.

Gold Hill in those early stages was mostly run by Americans so it has an English name. By the time it is owned and operated by (largely French) big business, the old name is mostly stuck. Also, fittingly, there were many 'Gold Hills' in OTL. The big strike in the Comstock Lode (which will get updates all of it's own later) has a Gold Hill as well.Very good chapter and interesting history of the gold rush that I did not know.

But if Gold Hill is operated by the French, shouldn't it be called " La Colline d'or" ?

In fact, it bears keeping in mind. Many of these roving prospectors are Americans/other non-French, because they have the least role in the rising French interests.

twovultures

Donor

'Gould eel' in the French pronunciation of the English words, maybe later turned into "Gouldille" in a fit of Francofication.Gold Hill in those early stages was mostly run by Americans so it has an English name. By the time it is owned and operated by (largely French) big business, the old name is mostly stuck. Also, fittingly, there were many 'Gold Hills' in OTL. The big strike in the Comstock Lode (which will get updates all of it's own later) has a Gold Hill as well.

In fact, it bears keeping in mind. Many of these roving prospectors are Americans/other non-French, because they have the least role in the rising French interests.

Probably fairly close to OTL, perhaps a bit larger. Say 400,000, most concentrated along the coast of course, with exceptions in Utah, and some old towns in Nouveau-Mexique (although ownership of these is debatable and will be covered in the next update, I think). Native American numbers are much higher then OTL but their numbers were (tens of thousands were killed and enslaved in OTL) too small to really effect the grand total.what's the total population of Californie in 1860s?

I wonder how Californie’s existence as an Overseas Department of France will affect the USA’s internal politics and economy?

I am trying to remain focused on the Californie in this TL but America will be a big part of the next TL installment, so we will get some hints.I wonder how Californie’s existence as an Overseas Department of France will affect the USA’s internal politics and economy?

Share: