Chapter Five: Trouble in Paradise

A Family Feud

~ ~ ~

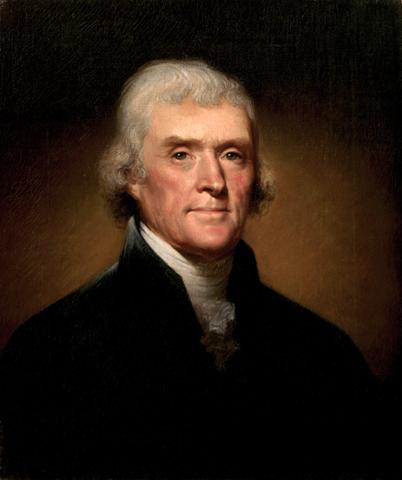

Alexander Hamilton (1797 – 1805), New York, Federalist Party

2nd President of New England and Protector of Her Liberties

“Let us recollect that peace or war will not always be left to our option; that however moderate or unambitious we may be, we cannot count upon the moderation, or hope to extinguish the ambition of others.”

— Alexander Hamilton, from the Federalist Papers

~ ~ ~

Chief Justice: Oliver Ellsworth (Connecticut, 1795 – 1805)

Secretary of State: Rufus King (New York, 1797 – 1805)

Secretary of War: Timothy Pickering (Massachusetts, 1797 – 1805)

Secretary of the Treasury: Oliver Wolcott, Jr. (Connecticut, 1796 – 1805)

Attorney General: Jared Ingersoll (Pennsylvania, 1797 – 1805)

Hamilton took office with just over 70% of the vote. Historians are divided on the issue of his majority in the first election. The flagpinned historians like to say that Hamilton rigged even his first election, that every paving stone on his path was an act of corruption. They paint a picture of Hamilton having run New England all along through a John Adams marionette, but the truth is a finicky thing. Objectivity is an eel that slips through your hands, and it’s been known to bite. The fact of the matter is that while Hamilton had many opponents, they were divided amongst themselves. Hamilton was the sole significant candidate of the Federalist Party, but there were three Republican candidates: Elbridge Gerry, George Clinton, and Aaron Burr. Aaron Burr was still turning Tammany Hall into a political machine that could rival Hamilton’s Society of the Cincinnati, and his feud with Clinton divided the vote. Gerry tried to remain aloof from the catfight of power politics and win the Republican vote by prestige. Unfortunately, his hermitage reduced him in the voters’ minds, and with his prestige came association with the Federalists. In my view, the more level-headed historians agree Hamilton only engaged in vote-rigging in his second-term bid. Then again, I’ve never been called level-headed, and it does take one to know one. Whether or not the Federalists stuffed the ballots for Hamilton in the Presidential Election of 1797, it’s clear he still would have won by a large majority. When my compatriots hear me write this way, they assume I apologize for Hamilton, or even argue in favor of his policies. I never apologize. I point the finger. My dear Yankees, our ancestors voted Hamilton into office. To deny that is not patriotism, but cowardice.

~ ~ ~

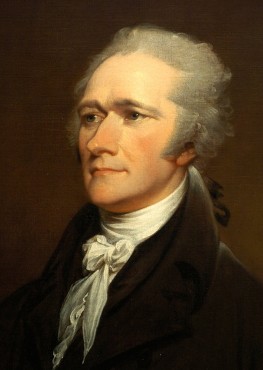

Nathanael Greene (1797 – 1805): Georgia, Democratic-Republican

2nd President of the United States of America

“We fight, get beat, rise, and fight again.”

— Greene on campaign during the Revolutionary War

~ ~ ~

Vice-President: Patrick Henry (Virginia, 1797 - 1799), James Madison (1799 – 1805)

Chief Justice: John Rutledge (South Carolina, 1789 – 1800), Bushrod Washington (Virginia, 1800 – 1829)

Secretary of State: James Monroe (Virginia, 1797 – 1799), Thomas Jefferson (Virginia, 1799 – 1805)

Secretary of War: Thomas Sumter (South Carolina, 1797 – 1805)

Secretary of the Treasury: James Madison (Virginia, 1797 – 1799), James Monroe (Virginia, 1799 – 1805)

Attorney General: John Breckinridge (Kentucky, 1797 – 1805)

Nathanael Greene was elected during the Pre-Party System in the United States. No political parties were officially recognized by the government, and most candidates ran under a “Democratic-Republican” ticket. There was a loose group of Federalists in the United States headed by South Carolina’s C. C. Pinckney, but it could hardly be considered a party. Federalism dominated New England, but it was weak in the South even before the disaster of the First Philadelphia Convention. After Hamilton’s rise to power, the word “Federalist” became a slur, and the Society of the Cincinnati in the United States broke entirely from the New England branch, electing President Nathanael Greene as its own President. Four candidates received significant shares of votes for office. Nathanael Greene won with 53% of the vote, Patrick Henry received 22% of the vote, James Madison 16%, and Charles Cotesworth Pinckney received 6%, with 3% of the vote belonging to various other write-in candidates. None of the candidates ran significant campaigns, but Greene’s particular brand of prestige gave him an edge even over the heady reputations of his opponents. Though he’d largely toed the line of the immensely popular Jefferson, he blanched at Jefferson’s reduction of the navy and relative neglect of the militia. It was evident that the United States could not avoid conflict with New England, and soon. Though Patrick Henry and James Madison were respected ideological leaders, Greene’s legacy seemed more relevant with war on the horizon. The people remembered his salvation of the South during the Revolution, how he’d pushed the British back to the sea where so many others gave ground. Greene was born a Yankee, but the South adopted him. Friends in Georgia offered him land at war’s end, and though he took time to acclimate to the new climate – he suffered sunstroke in 1786, but recovered soon after – he took to the landed life with ease. He retired from his military glory to live a planter’s life, but won second place in the first Presidential race, and agreed to take on the responsibility of Vice-President. When Jefferson declined to run again, Greene was the obvious choice to defend the Southern states once more.

~ ~ ~

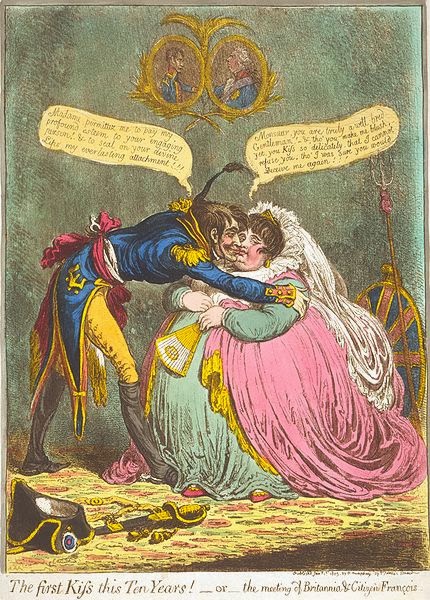

Disputes began to mount between our sister-nations from the moment they forged their separate paths. Besides their ideological divide and their opposing foreign leanings, the nebulous borders between the new states provided a host of flashpoints. Delaware was anything but secure with Maryland at its back. The Chesapeake peninsula was sparsely settled by farmers and fisherman, and the stone markers along the straight line of the Mason-Dixon did not make for a defensible border. The problems on the Chesapeake were only a pale imitation of the issues in the Northwest Territory, where there were no true borders between the claims of Yankee and American states. In the early days, most settlers banded together against outside threats regardless of nationality. After the Northwest Indian Wars solidified their countries’ positions over the Native populace, they shattered the brief peace. Perhaps without the issue of ideology, the settlers would not have been so quick to go for the throat. Yankee settlers knew that Americans like William Henry Harrison wanted to expand the South’s planter economy to the Northwest and encircle New England with slave states. American settlers knew that Yankees wanted to spread their banks and their factories along the Great Lakes, and if New England ate too big a slice of the Northwest cake, they could spread further across the Continent and become an even more dangerous enemy. Adams and Jefferson each battled the Natives of the territories East of the Mississippi. After a string of defeats over the Native confederacies, Adams appointed Henry Knox to headed New England’s campaign, while Jefferson appointed “Mad” Anthony Wayne to organize the United States’ effort. Both commanders recognized the need to train and discipline their disorganized militias, and the Presidents of their respective nations passed Militia Acts in 1792 to allow the necessary measures. In New England, the Whiskey Rebellion would demand a revision and expansion of the Militia Act in 1795 to provide for federal response to insurrection. The Barbary States had been hassling both the United States and New England. As the United States developed its coastguard and New England continued constructing its fleet, the Barbary States each made separates peaces with the twin nations. Adams had wrangled treaties with Algiers and Morocco in his final chaotic years in office, and the documents he’d prepared with Tripoli and Tunis were finalized in the beginning of Hamilton’s term. Adams grumbled as Yankee merchants cheered Hamilton’s name.

Though Henry Knox retired at the end of the Northwest Indian Wars that year, he kept in contact with his friend and ally Hamilton, and Hamilton called on his expertise once more when he took office. Hamilton had promised the post of Secretary of War to Timothy Pickering, his co-conspirator in Adams’ government, but Knox was uninterested in active government or military service. Still, Knox was Hamilton’s most important advisor on the Northwest situation. He advised Hamilton that New England’s position in the Northwest was untenable. New England’s somewhat tighter regulations on land speculation and settlement meant they had fewer boots on the ground, and Virginia’s claims overshadowed that of any other state. Knox was in a unique position to grasp the hanging vine that would lead New England out of her quagmire. He had surprisingly liberal views of the Native populace, despite or because of his battles with their tribes and confederations, and recognized them as sovereign nations, not as mere weeds to be culled from the garden. The fracture of the former colonies had sent the Native states into diplomatic disarray. The split from Britain already made the situation confusing. Before the Revolution, most Native Americans had little reason to differentiate the British from the colonists, and now even the colonists came under two flags. Knox and Hamilton were determined to capitalize on the confusion. Little Turtle was the most famous Native warleader on the Continent and a prominent member of the Miami tribe. The Yankee General St. Clair suffered the first great defeat of the Northwest Indian Wars to Little Turtle, but after being forced to sign a humiliating treaty, Little Turtle championed cooperation to preserve his people. Soon after Hamilton's election, the new President met with Little Turtle and presented the warleader with a ceremonial sword as a symbol of burgeoning alliance.

Little Turtle of the Miami

Hamilton and Greene each took office near the end of 1797, and they each capped the first year of their term with a bit of legislation. Hamilton passed the

Tariff of 1797 to increase the country’s tax base and the

Useful Manufactures Act to further protect and fortify New England’s growing industries, especially its naval factories. Greene passed the

Militia Reorganization Act of 1797, providing for better organization and training of its prospective military, still slapdash after the Militia Act of 1792.

1798 was a flurry of activity in New England. The Senate established the New England Marines and passed the

Naval Expansion Act of 1798, allowing for the construction of four additional frigates to join the six constructed during Adams’ term. The War of the First Coalition had dwindled by October of the previous year, but Britain remained at war, and a new Coalition coalesced. Hamilton expanded his international aims with

King’s Treaty. The Treaty affirmed the kinship between New England and Great Britain and put them on the same page when it came to the Northwest Territory. In the past, the British had funded Native American confederations to undermine their wayward colonials, but the Americans were entering the French orbit as New England mended bridges with her mother. King’s Treaty assured that the British would no longer support the Natives in their fight against Yankee interests. Instead, they’d funnel their funds to stem the tide of Americans coming up from the South. King’s Treaty outraged the United States and Yankee Republicans, but the Federalists dominated the Senate at the apex of their popular support. They passed the

Alien & Sedition Acts under the guise of national security to further entrench their party. The

Naturalization Act of 1798 increased the time required for naturalization to 14 years with 5 years advance notice (largely to restrict Irish immigrants, who usually became Republicans), the

Alien Friends Act and the

Alien Enemies Act allowed the President to imprison or deport aliens “dangerous to the peace and safety of the country,” or any citizen of a hostile nation within their borders over the age of 14, and the

Sedition Act restricted speech critical of the federal government, even allowing imprisonment in extreme cases in times of war. It’s hard to imagine how these autocratic laws could be put in place by a democratic government, but it’s all too easy to gloss it over with the Black Alexander Myth. Even the controversial Sedition Act was met with significant popular support, and that’s a truth we have to stomach.

Fries’ Rebellion broke out among the Pennsylvania Dutch in early 1799, the last insurrection against Federalist tax policies. The government crushed it in months and imprisoned many of the agitators.

Greene enjoyed support from all corners of the country and a cooperative government, but his cabinet still required reorganization. His Vice-President Patrick Henry and Chief Justice John Rutledge both died in 1799, forcing Greene to shake things up. James Madison, who had been his Secretary of Treasury, assumed the role of Vice-President, and Greene appointed Bushrod Washington the new Chief Justice. Jefferson returned from his restless retirement to become Greene’s new Secretary of State, and shifted Monroe to head the essential Treasury Department left open by Madison. Greene passed the

Naval Reconstruction Act, allowing for the construction of four frigates to prepare for impending war, but the Act would prove too little, too late. By the dawn of the next century, New England’s navy sported five frigates armed to the teeth – New York’s

NES President, Massachusetts’

NES Constitution, Pennsylvania’s

NES Federation, New Hampshire’s

NES Senate, and Rhode Island's

NES Liberty – with five more near completion. On February of 1800, the

NES Constitution fought and captured the French privateer Vengeance. After the

Constitution’s victory and capture of

L’Insurgence at the same time the last year, Hamilton felt the window of opportunity was finally open. After many deliberations on the issue, the Senate of New England declared war on the Republic of France for its diplomatic insults and its disruption of trade. Hamilton declared an end to foreign depredations and Jacobin extremism as the country approached the precipice of its destiny.

"For never can true reconcilement grow where wounds of deadly hate have pierced so deep...”

— John Milton, from

Paradise Lost