This kingdom of Syria, I feel like, will define the outremer. It has the potential to be the ulcer of byzantium; it's rich, densely populated, defensible, and looking to be stable. I just can't see a world in which byzantium can deal with them without bleeding themselves dry. And if byzantium can't deal with them cleanly, it'd probably be best to leave them be, and with that leeway they're free to undermine and influence Jerusalem all they want

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

And All Nations Shall Gather To It - Volume I: The Abode of Peace

- Thread starter Ricard (i.e. Rdffigueira)

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 90 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

65. The Fall of the Fatimid Caliphate 66. The Third War Between the Crusaders Interlude 5. The "Crusader States" as Historiographic Models 67. The Twilight of the Seljuks 68. The Jews and the Crusades Friendly Request: Contribute to the newly created Tv tropes Page 69. The Prophesized Emperors (Part 1) A not-so brief comment about my ideas for the TL@lusitano 1996 - Thanks for the compliment! As always, I'm trying to shorten the time between updates, but sometimes it's not easy.

@Sceonn - I believe @Quinkana and @NotAMyth gave entirely correct answers as to why Manuel is so focused in Egypt, from an economic (the expected rewards provide a positive net advantage than the expenditures) and political standpoint (the ideological motivation of restoring a former "core" province of the Roman Empire, seat of one of the five patriarchates).

I'd add another motivation, of more personal nature: Manuel ITTL, similarly to OTL, has had a mostly successful military record, and thus we cannot underestimate the psychological weight of having suffered through a defeat and desiring actual vindication against his former enemies. These points will be addressed in the next chapter, as will the difficulties of prosecuting another large-scale campaign so soon after another.

@St. Just - The point about Mabel's marriage is a narrative inconsistency that you very acutely observed! I should have mentioned in the chapter's commentary, but I "retconned" her second marriage, in-between the previous and the current installment. Indeed, in my original draft for these chapters, I had written some stuff about Ralph de Warenne, so as to explore some possible venue for a more significant Anglo-Norman presence in the Outremer, but I disliked how it was playing out, so, between the previous and the current chapter I changed my mind and "wrote him off" the TL. I'll have to rewrite the corresponding piece of the previous chapter to avoid confusion, but, to all the readers, keep in mind that the current write-up is the "canon": Mabel's second marriage is with Simon III of Montfort, not with Ralph.

[[Now that we've touched the subject, I've detected a not negligible number of minor and more relevant inconsistencies in the overall narrative, which, I figure, is something to be expected in a work going for so long in both years and actual size, with a serial format. I have already diagnosed some of these continuity issues, and I ask for the readers' help in this regard as well, to point out these issues. One example is the mentions I used to make to "Lebanon" and to "Lebanese" cities or peoples, but after some later reading, I found out it was a gross anachronism, considering that the usage of Lebanon for the actual region that the respective nation comprises dates from the middle 19th Century. So, all mentions to Lebanon will have to be substituted for either the rather antique "Phoenicia" or "western Syria" or something like that)

I intend to, once we finish the current Act, to undertake a general revision of all of the TL's chapters. In most of the cases this will result in very minor editions and corrections, but in a few others I'll do some "retcons" that I believe to be necessary to make the narrative more coherent.]]

As for Egypt, there's still a lot to go through! And interesting parallel about the Ottoman's fixture with Vienna. It makes a lot of sense.

The rebuilding of Homs certainly might have significant Oriental (Byzantine, Arab and likely even Armenian) influences in the architectural department. If there's one thing that characterized the Crusader-era building was pragmatism and eclecticism, and they drew from various influences.

@TickTock The Witch's Dead - Good question regarding the European dynasties.

Of all you mentioned the Wittelsbachs are the most likely to rise into prominence ITTL, even if due to different reasons. IOTL, they rose to power in Bavaria elevated by Frederick Barbarossa to eliminate the Welf presence in Bavaria during the wars with Henry the Lion; and they were, at least in their first generation, in the rule of Otto I Wittelsbach, very loyal to the Hohenstaufens. ITTL, as of the time being, the Wittelsbachs exist as an important, but comital-level Bavarian family, under the direct vassalage of Henry the Lion, who, besides being the Holy Roman Emperor, is also the Duke of Bavaria and of Saxony (whose patrimony will likely be partitioned during his own lifetime among his sons). Now, we must consider that, ruling a relatively immense imperial domain, that includes two "stem duchies" of the HRE and various Italian fiefs in Lombardy, Romagna, Tuscany and Spoleto, Emperor Henry the Lion will be expected to defer to the Saxon and Bavarian vassal dynasties to be actually able to reign and rule, meaning that the Wittelsbachs will be expectant of favoritism and feudal patronage. And here we have an interesting possible divergence: while IOTL Duke Henry the Lion focused his attention in Saxony, despite being also the recipient of Bavaria by inheritance (having founded various cities and castles in northern Germany, forming the core of Brunswick-Lunenburg, and championed the Wendish Crusade), the Bavarian vassal dynasties accumulated power and patrimony in his long absences from Bavaria. ITTL, Henry the Lion is the Emperor, and, similarly to Frederick Barbarossa, will often be needing to enter Italy to preserve the feudal control over the Matildine lands and to face the movements that led to the formation of the Lombard League, and this means that he will probably use Bavaria as the entrance from Germany to Italy, seeking to avoid the hostile territory of Swabia, and with this I'm convinced that he'll have to demonstrate some favoritism towards Bavaria and to the Bavarian families instead of towards Saxony and the Saxon nobility (which itself will produce huge divergences to the development of both regions of Germany).

The Luxembourgs also exist as a minor imperial house, but I'm still not sure if they'll become as relevant as OTL (which is predicated on them inheriting Bohemia and Brandenburg during the 14th Century). They probably will never achieve the imperial crown. Nonetheless, I want to explore a bit more the complicated situation and the possible divergences related to the Low Countries, so we might be hearing more about the Luxembourgs then.

Finally, the Habsburgs and the Visconti will certainly never even achieve relevance even on regional level. The causes of their rise into prominence IOTL cannot be replicated in this ATL. The Habsburgs because Austria won't be elevated to a more relevant feudal position, because it also happened due to the actions of Frederick Barbarossa; even if the Habsburgs inherit Austria, they will be vassals of the Duke of Bavaria, and this will severely limit their historical reach. The Visconti because Milan will remain under the direct rule of the Welfs and their later dynastic successors (the details of which I've yet to plan ahead), thus butterflying away the ascension of a local Milanese dynasty of communal origin.

On the other hand, dynasties that never did IOTL should become more relevant ITTL due to the respective divergences.

@DanMcCollum @ImperialxWarlord @galileo-034 - Thanks for the support as always!

Don't give your hopes for a single Crusader State yet (here meaning Palestine and Syria proper. I'm still figuring about Egypt, nothing definitive so far)! I don't want to explain too much right now, because this is obviously a WIP and sometimes I change parts of the writing "on the go" (this latest chapter, in fact, I had a lot of it written various weeks ago, but revised it almost from scratch because I wasn't satisfied with the draft. Sometimes it helps to discard the whole piece and start anew than to constantly revise it), but I find both scenarios - that of a single monarchical Crusader State, and that of at least two Crusader States, based respectively in Palestine and in Central Syria - to be very interesting in their own regard, and I believe that, given the current moment of the TL, there's good arguments to justify the plausibility of both scenarios.

While I have previously sketched and brainstormed both scenarios, and have written a "briefing" to analyze the future implications of both of them, I confess that, in this moment, I particularly "favor" the first scenario, of a united Outremer under a single monarchy. When we get there, I'll explain my reasons, but the main one (Watsonian POV) is that I think a united Frankish Syria and Palestine will have much better chances of survival in the long run, thus fulfilling one of the narrative "goals" of the TL, than a divided one. And from a Doylist POV, I think it should serve as an interesting contrast in relation to OTL. However, as always, let's see how things will play out. Nothing is set in stone in this TL, excepting the Mongols.

In any case, @galileo-034 mentioned, this realm, even if does gets to be politically united, will have important internal divisions driven by cultural and economic factors, which, by themselves, should be enough to foster political disputes for power and influence, and this will be another facet of the Outremerine society we must explore.

@Quinkana and @I HAVE BECOME GOD in the latest two posts brought to excellent observations: it is very much likely that, from their very beginnings in new "royal" format, with new political and administrative frameworks, the Crusader State (or States) will nonetheless see their centers of economic and political power gravitate towards the Syrian metropolises (Damascus, Homs/Emèse and likely also Tyre and Tripoli for the matter) in detriment of the region of Judaea proper. Jerusalem will always ever be the ideological fixture and raison d'étre of the kingdom, but in practical terms, it is far smaller in demographics and economics in comparison to various other cities, meaning that very much likely, ITTL, it won't be far-fetched to see the royal court more comfortable in some coastal metropolis or in even Damascus (if still existing more in an itinerant fashion as some of the royal courts of the period were).

@I HAVE BECOME GOD (#2,782) - As the latest chapters might have foreshadowed, Byzantium will have a rather complicated relationship with the Crusader State from now on. Not "Fourth Crusade" level-sh*tstorm, as I have emphasized in some other posts in this thread, but certainly they will never be really satisfied with playing second-fiddle. Due to the natural bellicosity of the Franks, I figure they are bound to have actual wars in the future, but these will never be existential threats to either of these states (we'd do well that IOTL the Komnenoi even in the height of their power did not go as far as extirpating the Principality of Antioch. I don't think it was about lack of resources, opportunity or conditions to do so, but because they saw a greater benefit in exploiting soft hegemonic power than actual military conquest; here ITTL it will be no different). These conflicts, when they do arise, will be local territorial disputes or settling of diplomatic grievances, but there's one significant advantage for both parties in avoiding the ultimate bad blood that existed ITTL [especially after the historical Second, Third and Fourth Crusades, all of which in any way or another resulted in direct conflicts between the European Crusaders and the Byzantines, and always resultant in a Byzantine humiliation], that is, they'll be much more inclined to preserve a defensive pact against non-Christian enemies than they did IOTL.

Adding Egypt to the equation will bring another whole layer of complexity, so we'll leave to address it later on.

@Sceonn - I believe @Quinkana and @NotAMyth gave entirely correct answers as to why Manuel is so focused in Egypt, from an economic (the expected rewards provide a positive net advantage than the expenditures) and political standpoint (the ideological motivation of restoring a former "core" province of the Roman Empire, seat of one of the five patriarchates).

I'd add another motivation, of more personal nature: Manuel ITTL, similarly to OTL, has had a mostly successful military record, and thus we cannot underestimate the psychological weight of having suffered through a defeat and desiring actual vindication against his former enemies. These points will be addressed in the next chapter, as will the difficulties of prosecuting another large-scale campaign so soon after another.

@St. Just - The point about Mabel's marriage is a narrative inconsistency that you very acutely observed! I should have mentioned in the chapter's commentary, but I "retconned" her second marriage, in-between the previous and the current installment. Indeed, in my original draft for these chapters, I had written some stuff about Ralph de Warenne, so as to explore some possible venue for a more significant Anglo-Norman presence in the Outremer, but I disliked how it was playing out, so, between the previous and the current chapter I changed my mind and "wrote him off" the TL. I'll have to rewrite the corresponding piece of the previous chapter to avoid confusion, but, to all the readers, keep in mind that the current write-up is the "canon": Mabel's second marriage is with Simon III of Montfort, not with Ralph.

[[Now that we've touched the subject, I've detected a not negligible number of minor and more relevant inconsistencies in the overall narrative, which, I figure, is something to be expected in a work going for so long in both years and actual size, with a serial format. I have already diagnosed some of these continuity issues, and I ask for the readers' help in this regard as well, to point out these issues. One example is the mentions I used to make to "Lebanon" and to "Lebanese" cities or peoples, but after some later reading, I found out it was a gross anachronism, considering that the usage of Lebanon for the actual region that the respective nation comprises dates from the middle 19th Century. So, all mentions to Lebanon will have to be substituted for either the rather antique "Phoenicia" or "western Syria" or something like that)

I intend to, once we finish the current Act, to undertake a general revision of all of the TL's chapters. In most of the cases this will result in very minor editions and corrections, but in a few others I'll do some "retcons" that I believe to be necessary to make the narrative more coherent.]]

As for Egypt, there's still a lot to go through! And interesting parallel about the Ottoman's fixture with Vienna. It makes a lot of sense.

The rebuilding of Homs certainly might have significant Oriental (Byzantine, Arab and likely even Armenian) influences in the architectural department. If there's one thing that characterized the Crusader-era building was pragmatism and eclecticism, and they drew from various influences.

@TickTock The Witch's Dead - Good question regarding the European dynasties.

Of all you mentioned the Wittelsbachs are the most likely to rise into prominence ITTL, even if due to different reasons. IOTL, they rose to power in Bavaria elevated by Frederick Barbarossa to eliminate the Welf presence in Bavaria during the wars with Henry the Lion; and they were, at least in their first generation, in the rule of Otto I Wittelsbach, very loyal to the Hohenstaufens. ITTL, as of the time being, the Wittelsbachs exist as an important, but comital-level Bavarian family, under the direct vassalage of Henry the Lion, who, besides being the Holy Roman Emperor, is also the Duke of Bavaria and of Saxony (whose patrimony will likely be partitioned during his own lifetime among his sons). Now, we must consider that, ruling a relatively immense imperial domain, that includes two "stem duchies" of the HRE and various Italian fiefs in Lombardy, Romagna, Tuscany and Spoleto, Emperor Henry the Lion will be expected to defer to the Saxon and Bavarian vassal dynasties to be actually able to reign and rule, meaning that the Wittelsbachs will be expectant of favoritism and feudal patronage. And here we have an interesting possible divergence: while IOTL Duke Henry the Lion focused his attention in Saxony, despite being also the recipient of Bavaria by inheritance (having founded various cities and castles in northern Germany, forming the core of Brunswick-Lunenburg, and championed the Wendish Crusade), the Bavarian vassal dynasties accumulated power and patrimony in his long absences from Bavaria. ITTL, Henry the Lion is the Emperor, and, similarly to Frederick Barbarossa, will often be needing to enter Italy to preserve the feudal control over the Matildine lands and to face the movements that led to the formation of the Lombard League, and this means that he will probably use Bavaria as the entrance from Germany to Italy, seeking to avoid the hostile territory of Swabia, and with this I'm convinced that he'll have to demonstrate some favoritism towards Bavaria and to the Bavarian families instead of towards Saxony and the Saxon nobility (which itself will produce huge divergences to the development of both regions of Germany).

The Luxembourgs also exist as a minor imperial house, but I'm still not sure if they'll become as relevant as OTL (which is predicated on them inheriting Bohemia and Brandenburg during the 14th Century). They probably will never achieve the imperial crown. Nonetheless, I want to explore a bit more the complicated situation and the possible divergences related to the Low Countries, so we might be hearing more about the Luxembourgs then.

Finally, the Habsburgs and the Visconti will certainly never even achieve relevance even on regional level. The causes of their rise into prominence IOTL cannot be replicated in this ATL. The Habsburgs because Austria won't be elevated to a more relevant feudal position, because it also happened due to the actions of Frederick Barbarossa; even if the Habsburgs inherit Austria, they will be vassals of the Duke of Bavaria, and this will severely limit their historical reach. The Visconti because Milan will remain under the direct rule of the Welfs and their later dynastic successors (the details of which I've yet to plan ahead), thus butterflying away the ascension of a local Milanese dynasty of communal origin.

On the other hand, dynasties that never did IOTL should become more relevant ITTL due to the respective divergences.

@DanMcCollum @ImperialxWarlord @galileo-034 - Thanks for the support as always!

Don't give your hopes for a single Crusader State yet (here meaning Palestine and Syria proper. I'm still figuring about Egypt, nothing definitive so far)! I don't want to explain too much right now, because this is obviously a WIP and sometimes I change parts of the writing "on the go" (this latest chapter, in fact, I had a lot of it written various weeks ago, but revised it almost from scratch because I wasn't satisfied with the draft. Sometimes it helps to discard the whole piece and start anew than to constantly revise it), but I find both scenarios - that of a single monarchical Crusader State, and that of at least two Crusader States, based respectively in Palestine and in Central Syria - to be very interesting in their own regard, and I believe that, given the current moment of the TL, there's good arguments to justify the plausibility of both scenarios.

While I have previously sketched and brainstormed both scenarios, and have written a "briefing" to analyze the future implications of both of them, I confess that, in this moment, I particularly "favor" the first scenario, of a united Outremer under a single monarchy. When we get there, I'll explain my reasons, but the main one (Watsonian POV) is that I think a united Frankish Syria and Palestine will have much better chances of survival in the long run, thus fulfilling one of the narrative "goals" of the TL, than a divided one. And from a Doylist POV, I think it should serve as an interesting contrast in relation to OTL. However, as always, let's see how things will play out. Nothing is set in stone in this TL, excepting the Mongols.

In any case, @galileo-034 mentioned, this realm, even if does gets to be politically united, will have important internal divisions driven by cultural and economic factors, which, by themselves, should be enough to foster political disputes for power and influence, and this will be another facet of the Outremerine society we must explore.

@Quinkana and @I HAVE BECOME GOD in the latest two posts brought to excellent observations: it is very much likely that, from their very beginnings in new "royal" format, with new political and administrative frameworks, the Crusader State (or States) will nonetheless see their centers of economic and political power gravitate towards the Syrian metropolises (Damascus, Homs/Emèse and likely also Tyre and Tripoli for the matter) in detriment of the region of Judaea proper. Jerusalem will always ever be the ideological fixture and raison d'étre of the kingdom, but in practical terms, it is far smaller in demographics and economics in comparison to various other cities, meaning that very much likely, ITTL, it won't be far-fetched to see the royal court more comfortable in some coastal metropolis or in even Damascus (if still existing more in an itinerant fashion as some of the royal courts of the period were).

@I HAVE BECOME GOD (#2,782) - As the latest chapters might have foreshadowed, Byzantium will have a rather complicated relationship with the Crusader State from now on. Not "Fourth Crusade" level-sh*tstorm, as I have emphasized in some other posts in this thread, but certainly they will never be really satisfied with playing second-fiddle. Due to the natural bellicosity of the Franks, I figure they are bound to have actual wars in the future, but these will never be existential threats to either of these states (we'd do well that IOTL the Komnenoi even in the height of their power did not go as far as extirpating the Principality of Antioch. I don't think it was about lack of resources, opportunity or conditions to do so, but because they saw a greater benefit in exploiting soft hegemonic power than actual military conquest; here ITTL it will be no different). These conflicts, when they do arise, will be local territorial disputes or settling of diplomatic grievances, but there's one significant advantage for both parties in avoiding the ultimate bad blood that existed ITTL [especially after the historical Second, Third and Fourth Crusades, all of which in any way or another resulted in direct conflicts between the European Crusaders and the Byzantines, and always resultant in a Byzantine humiliation], that is, they'll be much more inclined to preserve a defensive pact against non-Christian enemies than they did IOTL.

Adding Egypt to the equation will bring another whole layer of complexity, so we'll leave to address it later on.

Last edited:

I'm not quite sure of that.The Visconti because Milan will remain under the direct rule of the Welfs and their later dynastic successors (the details of which I've yet to plan ahead), thus butterflying away the ascension of a local Milanese dynasty of communal origin.

The rise of the Viscontis was correlated with the communal movement at large, of which the Lombard league were but a symptom and one especially more powerful in Italy than elsewhere in Europe. Even if the Welfs are more powerful dynasts than the Emperors were IOTL, I don't see how they can squash that movement in Lombardy, and that's especially minding that we are heading towards a long period of conflicts between the Capetians and the Welfs, a HYW style one if that's still the idea. And that's a conflict which will unavoidably lead to increased fiscal pressure across Welf domains, especially in Lombardy and Tuscany; we know from OTL how much the Italian communes loved these taxes.

Probably Phoenicia, since that's the name from ancient times.So, all mentions to Lebanon will have to be substituted for either the rather antique "Phoenicia" or "western Syria" or something like that)

I'll have to check over the updates on my favourite Montpellier guilhemid branch in the Levant ^^. I think they had either Caesarea or Acre at a point, but don't see where they are now.Now that we've touched the subject, I've detected a not negligible number of minor and more relevant inconsistencies in the overall narrative, which, I figure, is something to be expected in a work going for so long in both years and actual size, with a serial format. I have already diagnosed some of these continuity issues, and I ask for the readers' help in this regard as well, to point out these issues.

I wouldn't be so pessimistic. Geopolitically, Jerusalem still commands, with its control of Palestine and Outrejourdain (more likely to gravitate towards Jerusalem than towards Damascus) a strategic position. Being at the crossroads of Egypt, Syria and Hejaz, it controls major trade and pilgrim routes in the region, both for Christians and Muslims, which means a lot of revenues from trade and taxes, provided the roads can be kept safe. Unless Jerusalem is politically and militarily subjected to Damascus, being sovereign over Palestine-Outrejourdain means whoever rules it has a lever effect to balance the sheer demographic and economic weight of Syria, not just because of the symbolic nature of Jerusalem.Jerusalem will always ever be the ideological fixture and raison d'étre of the kingdom, but in practical terms, it is far smaller in demographics and economics in comparison to various other cities, meaning that very much likely, ITTL, it won't be far-fetched to see the royal court more comfortable in some coastal metropolis or in even Damascus (if still existing more in an itinerant fashion as some of the royal courts of the period were).

Really enjoying reading this TL. Just a few questions:

What are community relations like amongst the general population of the Levant/Outremer?

As far as I am aware while the Near East retained a Christian plurality during the time, there was a significant growing Muslim minority, how have they reacted to recent developments with their Christian overlords?

What are community relations like amongst the general population of the Levant/Outremer?

As far as I am aware while the Near East retained a Christian plurality during the time, there was a significant growing Muslim minority, how have they reacted to recent developments with their Christian overlords?

I'd think it's possible that the welfs keep Italy together although the various city states have their own commune that runs their own affairs.The rise of the Viscontis was correlated with the communal movement at large, of which the Lombard league were but a symptom and one especially more powerful in Italy than elsewhere in Europe. Even if the Welfs are more powerful dynasts than the Emperors were IOTL, I don't see how they can squash that movement in Lombardy, and that's especially minding that we are heading towards a long period of conflicts between the Capetians and the Welfs, a HYW style one if that's still the idea. And that's a conflict which will unavoidably lead to increased fiscal pressure across Welf domains, especially in Lombardy and Tuscany; we know from OTL how much the Italian communes loved these taxes.

I think if Jerusalem is in a rough patch tho Syria could easily conquer them if the Syrians play their cards well. It's also the fact that the Mongols are coming. I still think that Jerusalem would do the best as an administrative capital due to the clout/history and it's good defensive position.I wouldn't be so pessimistic. Geopolitically, Jerusalem still commands, with its control of Palestine and Outrejourdain (more likely to gravitate towards Jerusalem than towards Damascus) a strategic position. Being at the crossroads of Egypt, Syria and Hejaz, it controls major trade and pilgrim routes in the region, both for Christians and Muslims, which means a lot of revenues from trade and taxes, provided the roads can be kept safe. Unless Jerusalem is politically and militarily subjected to Damascus, being sovereign over Palestine-Outrejourdain means whoever rules it has a lever effect to balance the sheer demographic and economic weight of Syria, not just because of the symbolic nature of Jerusalem.

The thing that Kingdom of Jerusalem does really well in my opinion, is as a place to send those looking for military glory. You might see a more peaceful Europe to some extent over time compared to OTL just because rebellious sons and those leaders or generals seen as troublemakers looking to make war can be sent to the Holy land instead to fight the Muslim armies.

I am particularly thinking of the HRE'S control of Italy and Germany might be massively impacted by this since the HRE will likely be able to send troublesome leaders to the Holy land instead.

I am particularly thinking of the HRE'S control of Italy and Germany might be massively impacted by this since the HRE will likely be able to send troublesome leaders to the Holy land instead.

Last edited:

I could also see them being sent to North Africa too.The thing that Kingdom of Jerusalem does really well in my opinion, is as a place to send those looking for military glory. You might see a more peaceful Europe to some extent over time compared to OTL just because rebellious sons and those leaders or generals seen as troublemakers looking to make war can be sent to the Holy land instead to fight the Muslim armies.

I am particularly thinking of the HRE'S control of Italy and Germany might be massively impacted by this since the HRE will likely be able to send troublesome leaders to the Holy land instead.

Possible, perhaps. Probable, feasible? Rather not. Too many players, too many ambitions... The Pope, the Normans, the Venitians, the Byzantines, the Capetians...I'd think it's possible that the welfs keep Italy together although the various city states have their own commune that runs their own affairs.

The city states in Italy of OTL weren't just content with running their own affairs in their own corners, they were aggressively pursuing opportunities of trade and commerce, more often than not at the expanse of neighboring cities, a game played by the likes of Milan, Venice, Genoa, Florence to just cite the most famous... Well, who remembers the names of these cities they rolled over during their expansion? Oh, I just remembered Florence subjugating Pisa, Volterra, Siena, or Venice carving up the terra firma.

The Lombard league happened because they didn't quite accept being restrained from expanding by the Emperor. As I see it, the dynamic of OTL is quite unavoidable.

And the strength of the Welf dynasty is not quite at their advantage. A stronger Emperor will likely mean a more affirmed and present authority, which will probably lead to earlier or bigger resentment. If you add the Capetians lurking across the Alps with the Anscarids in their bags as credible rival claimants on the Italian throne, the Byzantines in southern Italy ever in ambush and waiting opportunities of reversing five centuries of losses in the peninsula, or even unreliable Popes ever doing switcharoos between the often conflicting aims of furthering their temporal influence across Italy at the expanse of imperial authority and their spiritual supremacy to defend against heresies and anti popes , you'll find that the Welf position in Italy is quite precarious at this time.

The major difference from Frederick Barbarossa is that they have a permanent presence in the peninsula with their family holdings, but that will at best delay the dynamic. The Welfs can only do so much if they are stretched all the way from the Low countries to Rome.

Feasible indeed. But in the patchwork of competing ambitions, that's the safest way to make unanimity against them. And with Egypt coming into the Franks sphere, you'd have Palestine becoming once again a battleground between Egypt and Syria, like between Fatimids and Seljuks, or between Ptolemaids and Seleucids...I think if Jerusalem is in a rough patch tho Syria could easily conquer them if the Syrians play their cards well. It's also the fact that the Mongols are coming. I still think that Jerusalem would do the best as an administrative capital due to the clout/history and it's good defensive position.

64. The Second Rhōmaíōn War For Egypt

64. The Second Rhōmaíōn War For Egypt

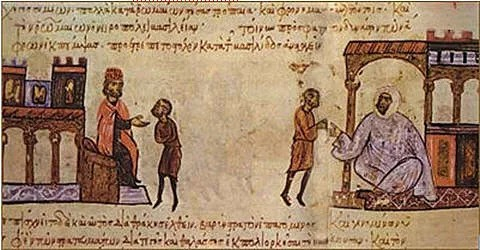

Detail of a Miniature depicting the exchange of envoys between Manuel I Komnenos and a Fāṭimid Prince, who is thought to represented al-Malik al-Ghazi. From a 14th Century Manuscript of the "Summary of the feats of the late emperor and purple-born lord John Komnenos and narration of the deeds of his celebrated son the emperor and purple-born lord Manuel I Komnenos done by John Kinnamos his imperial secretary" of John Kinnamos. The artwork is in fact based in an older manuscript created in Sicily illustrating the Synopsis of History of John Skylitzes

[IOTL, the art comes from the "Madrid Skylitzes]

I. Of the Actions and Vigor of the Last Grand Vizier of the Fāṭimid Caliphate

Detail of a Miniature depicting the exchange of envoys between Manuel I Komnenos and a Fāṭimid Prince, who is thought to represented al-Malik al-Ghazi. From a 14th Century Manuscript of the "Summary of the feats of the late emperor and purple-born lord John Komnenos and narration of the deeds of his celebrated son the emperor and purple-born lord Manuel I Komnenos done by John Kinnamos his imperial secretary" of John Kinnamos. The artwork is in fact based in an older manuscript created in Sicily illustrating the Synopsis of History of John Skylitzes

[IOTL, the art comes from the "Madrid Skylitzes]

I. Of the Actions and Vigor of the Last Grand Vizier of the Fāṭimid Caliphate

In Egypt, the great Turkoman Vizier who had vanquished the Rhõmaîoi and the Franks, al-Malik al-Ghazi al-Mansur [literally meaning "The Most Victorious Prince Devoted to the Holy War"] spent the better part of the previous decade combating the Almohads. The Berbers had come to Egypt first as allies, but soon enough their deception fell and they revealed themselves to be enemies of the Shia Caliphate. Led by the Berber Sheikh Abū Ḥafṣ ʿUmar ibn Yahya [1], they inflicted a significant defeat upon the Fāṭimids, and months later raided the environs of Fustat. Their mobile force of horsemen and camelmen many times eluded the Egyptians, and, while they did not succeed in taking any settlements whatsoever, their raids nonetheless provoked unwanted devastation in the lands irrigated by the Canopic branch of the Nile. The destruction and ransacking of the local farming estates impoverished the rural populations and forced them to flee to more populous settlements, provoking in turn two consecutive years of famine and epidemics due to the abrupt demographic transitions.

Worse even to the Egyptians was the fact the Almohads had convinced many Bedouin chieftains hitherto affiliated to the Fāṭimids to desert to their own side, promising that, once the heretic Imam and Caliph had been dethroned, they would be the actual rulers and governors of Egypt under the purview of the righteous Sunni Almohads. Not a few of them, in fact, converted to from Ismailism to Sunnism, introducing a new religious dimension to the conflict.

Despite their tactical successes, however, the overall strategic advantage still belonged to the Fāṭimids, and soon the Almohads, facing insurmountable logistical constraints and unable to dedicate themselves to long-lasting siege operations, for the Berber and Bedouin soldiers were ever more interested in easy plunder than in capturing fortresses and cities, Abū Ḥafṣ was forced to abandon their encampment near Alexandria in 1170 A.D. and retreat to Cyrenaica. When they fell back to Barqa, though, the Bedouins who had joined him broke off and took their own path, preferring to entrench themselves in the cluster of towns and caravanserai of the Siwa oasis. Thus, even after enjoying significant victories, the Almohad offensive dissipated into a collection of roving warbands dedicated to raiding the extensive frontier of the western desert of Egypt.

Al-Malik al-Ghazi saw the treacherous Bedouins as the more immediate threat to his power, considering that they had been formerly subjects of the Fāṭimid Caliph, and, certainly fearing sedition from among the other segments of the Caliphal army, he launched a dedicated punitive expedition against them. In a single campaign, he stormed the newly-constructed ribāṭ in Siwa, and slaughtered the desert peoples to their last man. Considering that the Bedouins were nomads, however, this hardly impacted in their demographics or in their actual military presence in the western desert, but it did serve to consolidate al-Ghazi’s image as a merciless warrior.

Afterwards, between 1171 and 1173, he marched into Cyrenaica to recover the province back to the Caliphate, and, over the course of three war campaigns, he retook Tobruk, Barca and Berenice, in each occasion giving no quarter to the defeated Berbers, who were slain to the last soldier. Once again, however, these victories, however, did little to secure definitive victory in the war, for the presence of the Almohads east of Ifriqiya was much fluid and elusive; the so-called Almohad Caliph had obtained the allegiance of many tribes and clans who roamed across the Maghreb, and their nomadic lifestyle, while it made them poorly suited to perform long-lasting siege operations or garrison duty, inspired them with hit-and-run tactics and raids that jeopardized the lines of communication and of supply.

The last act of the campaign happened when al-Ghazi’s lieutenants ventured into the desert for the second time and successfully captured the oasis of Awjila, where they demolished another recently-built Berber fortress. But it was in Syrte, in the Tripolitanian coast, that the Fāṭimid mamluks faced another Caliphal army, in 1174 A.D., led by Emir Abū Ḥafṣ, who, this time, suffered a clear defeat.

Only then did the Almohad Caliph sent envoys to conclude a truce between the warring Caliphates. While the human casualties had not been all too significant in the Berber side, and the loss of some coastal settlements under a de facto autonomous rule of local emirs hardly affected the political and economic core of the Almohad Caliphate, situated in the Maghreb al-Aqsa [literally meaning "the Farthest West"], the cost-opportunity of the conflict became too high; Caliph Abū Ya‘qūb Yūsuf had expected an easy conquest to satiate the appetite of his subordinate chieftains for plunder - in this case, more of the Berbers than of the Bedouins -, perhaps trusting that religious fervor alone could animate the soldiers to storm walled cities and citadels. Yet, rapine-minded tribesmen and dispirited mercenaries lacked the necessary resolve to engage in a protracted war so far from their homes, where the logistical network of the Almohads was beyond stretched. The campaign had seen impressive advances, but it was a doomed effort nonetheless, and it was about time for the Moroccans to direct their attention to nearer and more relevant conquests, in Al-Andalus, against the insolent Christian kingdoms of Iberia.

********

Al-Malik al-Ghazi hastily accepted the terms of a five-year truce with the Almohads. In spite of the strategic success, the war in the western Nile and in Cyrenaica had been an ulcer in the manpower of the realm and in the finances of the state, both of which had been gravely afflicted by the destructive Christian invasion of the previous decade. Yet, the tireless warmonger - who had grown since early age in the barracks, and lacked any administrative experience whatsoever - saw in war itself the solution to other predicaments of the realm, believing that unity and stability could be achieved as consequences of military triumphs. This perhaps explains why he failed to see the troubles that had been brewing during his long absences to prosecute military campaigns.

Regardless of his impressive victories, and even of the fact that he was genuinely loyal to the Caliphate, al-Malik’s reign had rapidly grown all too unpopular among the masses, and the disgruntled elements of the central administration and of the army found easy ground to exploit the grievances, even more now that the Shia religious fervor against the Sunni and the non-Islamic minorities became an infallible tool to harness. In an effort to secure his power and his position, he placed his colleagues and trusted officers in the dīwān and other high offices and ministries of the state, in detriment of experienced bureaucrats, and his lieutenants were given the governorship of important provinces such as Alexandria. To demote Christians and Jews from these offices was easy enough, because they could hardly complain; but when he evicted fellow Muslims, he became especially vilified, especially among the palatine eunuchs, who formed an influential political faction in Cairo. In any case, they knew it was but a matter of time before the results of replacing professional clerks by illiterate soldiers to manage the complex governmental machinery revealed themselves. And, indeed, by 1174 A.D., as al-Malik al-Ghazi was in the western Sinai preparing for a campaign against the Franks in Palestine, the problems, rather predictably, had been accumulating, especially due to the rampant administrative inefficiency and fiscal debility of the upper echelon and provincial government, not in the least helped by the fact that most of the Mamluk officers reveled in perpetrating arbitrary acts against civilians, such as wanton expropriations, and in plundering the public coffers.

The straw the broke the camel’s back and ignited an outright rebellion against al-Malik al-Ghazi and his Mamluks occurred after he belatedly attempted to disband the Rayhāniyya, the regiment of the Sudanese [2], one numbering tens of thousands, long since been established in Fustat as a sort of provincial garrison in the capital, and thus also held significant political influence. What the Vizier did not know is that the Rayhāniyya had allied to the Juyūshiyya, the regiment originally formed by Muslim Armenians - by then comprised mostly by native Egyptians, Syrians and Turkomans and only but a few ethnic Armenians - owing to the mediation of Mu’tamin al-Khilāfa, a palatine eunuch who effectively governed Cairo during al-Malik's absence. While perhaps predicting a few instances of insubordination, the Vizier could not have foreseen that these regiments - who were bitter rivals in the disputes to control the government and had barely three decades ago been in opposing sides of a dynastic war, during the reign of Caliph al-Ḥāfiẓ - would join together in a massive mutiny. Even worse, the eunuchs, with the blessing of Caliph al-ʿĀḍid himself, concocted a popular uprising among the inhabitants of Fustat, arguing that al-Malik al-Ghazi was an usurper who intended to depose the Caliphate and install a new Sunni-led regime headed by himself as Imam; a delusional but convincing scenario to the majoritarian Shia population of Fustat, whose dissatisfaction with the growing Sunni presence in Egypt was at its highest point. The frenzied mobs massively bolstered the rebellious army and they easily overpowered and slew the Mamluks - whose discipline had laxed over the course of years of garrison duty in the luxurious Caliphal palace -, before turning their hateful violence against the hapless Sunni Muslims currently living in Fustat.

Ousted from the capital, the Mamluks under al-Malik al-Ghazi retreated to Bilbeis, and from there, once the rebels approached, to Alexandria. Mu’tamin placed the Yemeni Emir Husayn ibn Abu ʾl-Hayjā as de jure vizier, with he himself as the power-behind-the-throne. Then, they pleaded for the assistance of the Hamdanids and the Zurayids of Yemen to defeat the Mamluks, and they, who had long since given allegiance to the Fāṭimids, accepted and sent across the Red Sea reinforcements of two thousand spear-men.

Yet again, Egypt was wrecked by intestine strife [3], in an eerie echo from the catastrophic reign of Caliph al-Mustanṣir, during which, exactly a hundred years before, the realm saw climatic-induced calamities and the usurpation of the legal government by Turkish mercenaries commanded by Nasir al-Dawla ibn Hamdan [4]. At the time, the Turks were humbled and pacified by the efforts of the Armenian general Badr al-Jamali, but the symptoms of the infirmity of the Caliphal government were evident ever since, characterized, as we have previously described in this Chronicle, by violent political factionalism and religious fanaticism. Now, al-Malik al-Ghazi might have very well been a second hope, if not for a genuine restoration of the Caliphate’s fortunes, at least of delaying its seemingly inevitable demise - but even though he was a great man, he was a man nonetheless, and thus incapable of alone overturning the fate of the dynasty and of the state. Now, fortune would not favor the Caliphate, and it was in this context, in which the last figments of Caliphal authority were dissipating due to the infighting of the military contingents, and governmental and institutional organization were collapsing due to corruption, concurred by the constant raiding and violence of the Berbers in the western frontier, that Basileus Manuel Komnenos of the Rhõmaîon Empire, still coveting the riches of Egypt and the glory of a triumph, launched a second invasion of the realm of the Nile.

II. Of Manuel's Desire For an Egyptian Triumph

Even today we can not know for certain of how much the Rhõmaîon Basileus was aware about the domestic strife in Egypt in the year of 1174 A.D. From contemporary sources, we garner that his invasion was produced rather fortuitously, as if the Rhõmaîoi and the Franks simply happened to launch this organized offensive against Egypt and then stumbled upon the Fāṭimid leadership engaged in an intestine war. Modern historians are skeptical of this, and, instead, consider that it was very probable that Manuel and his inner court circle ought to have known, in the very least, that al-Malik al-Ghazi had been expelled from Fustat and a new vizier had been installed, and that this event created the opportunity that he apparently had been awaiting for. A compelling argument has been forwarded in Britannian academic circles claiming that, unlike in the previous opportunity, where the Armenians had provided much-needed intelligence to the Rhõmaîon government, this time Manuel’s agents collected intelligence from among the Constantinopolitan Jews, who had important commercial and social ties with the Jewish community of Alexandria - this being evidenced, for example, by the fact that Maimonides’ works, written during these years became immediately accessible to the Jews living in Greece as well as to those living in al-Andalus [5].

Whatever might be the Manuel’s knowledge about the circumstances, it is very clear from the contemporary sources that he had never quite abandoned the desire of subjugating Egypt; it seems that he had planned to prosecute a second invasion scantily after securing the truce with Sicily and Hungary, but was discouraged from doing so by the Basilissa and his most trusted courtiers, such as John Doukas Komnenos - who had himself coordinated the war theater in the Basileus’ absence - and Theodore Vatatzes, who feared that his departure for another long-lasting campaign would inspire palatine conspiracies and even rebellions. Niketas Choniates mentions that many courtiers feared the growing influence of Manuel’s cousin Andronikos Komnenos - who had returned from exile after the war against the Hungarians, and, once pardoned for having participated in a previous conspiracy, was readmitted into the imperial court, where he became one of the Emperor’s favorites, sharing with him the fascination with astrology and supporting Manuel’s every whims [6].

As it came to be, however, the event of the war itself, with its massive expenditures and significant casualties, had troubled both the aristocrats and the bureaucrats alike - the former because they, under the institutional system crafted by Alexios and John Komnenos, were expected to provide military service and economic assistance to the state in such wars, and the latter because they had to solve complex administrative issues with dwindling resources. Even worse was the fact that the conscription and tax-exaction undertaken in the previous years to replenish the military manpower and public treasury had incurred in the dissatisfaction of the peasantry, especially among the Bulgarians and the Vlachs, who believed to be suffering the worst of the financial burden. Armed insurgency occurred in only a few instances in the Bulgarian countryside, and they were easily quenched by provincial armies, but the situation, to more sensible courtiers in the imperial ministries, was alarming, and they feared more significant revolts. It did not help Manuel the fact that, if before there was at least some quiet moral support to the Crusadist doctrine sponsored by the Basileus, now there was active discontentment from among many Greek bishops and monasteries towards the very idea of a “holy” war, seen as morally abhorrent and as a Latin Catholic, and thus unorthodox, influence. The current Patriarch, Michael III, in spite of being Manuel’s personal friend and one of his most dedicated supporters, made no argument to sustain the Emperor’s cause in this regard, and thus Manuel cautiously and studiously avoided to use the Crusadist rhetoric which he had so eagerly embraced before.

Regardless of these various predicaments, Manuel was still massively popular in Constantinople and in the core provinces of Rhõmãnia, and inspired intense loyalty from the aristocratic families which had been bonded by marriage to the Komnenoi, such as the Doukaioi, the Vatatzioi, the Bryennioi and the Kantakouzenoi, and even from the Armenians, whose bellicose spirit had long since animated rebellious dissent against the Empire, but in his reign were mostly cooperative.

The Basileus held a very pragmatic vision of how to reign and to solve the matters of the state. He believed that the conquest and annexation of Egypt, for all its present riches, for its agrarian production and for its position in the commercial networks of Africa and Asia, would easily compensate for the expenses of the campaign. Even more, he decided to sustain the war effort with minimal casualties from his own subjects by drawing mercenary troops from the foreign races instead of from among the citizenry. And, at last, he once again summoned reinforcements from Hungary - whose new monarch, Béla III was Manuel’s son-in-law [7] and had formerly been a distinguished member of the Constantinopolitan court, before acceding to the Hungarian throne in 1172 - and from Serbia - whose prince, Stefan Nemanja, had accepted Manuel’s suzerainty after the death of the Hungarian King Stephen III [8]. And, of course, he too summoned the allegiance of the Franks of the Levant, under the leadership of Raymond III of Caesarea, who was obliged to present two hundred knights and six thousand infantrymen.

John Kinnamos, who actually participated in the campaign, calls it “a grand army of barbarians” - perhaps unwilling to withhold his prejudice and moral judgment because he wrote his chronicle years after the events, knowing in hindsight about its later disastrous outcome -; he stresses that while the army that Manuel constituted ten years before had been a large army of Rhõmaîoi citizen-soldiers assisted by significant foreign mercenaries, this one was a large army of foreign mercenaries assisted by significant Rhõmaîoi citizen-soldiers. Many of them were not actual mercenaries, such as the Cilician Armenians, the Pechenegs and the Anatolian Turkomans [9], all of whom had been absorbed into the Empire’s social, economic and military structures ever since the very beginning of the 12th Century, being thus imperial subjects, although they were indeed culturally distinctive in relation to the Rhõmaicized Greek and Anatolian peoples, having retained their customs, tribal and clan structures, their languages and, in the case of the Turks, most of them remained Muslims. On the other hand, there was a markedly smaller number of Latinikon troops - most of the active ones in imperial service being Siculo-Normans and Lombards -, with the large part of the actual “foreigners” being the pagan Cumans. There is also the mention of a small contingent of Georgian archers, ceded by King George III.

*****

Whereas the first expedition had been distinguished by the impressive and intricate logistical apparatus devised to sustain the march, the camp and the operation of the army, in this one, Manuel and his agents failed to produce a supportive network adequate to the size of the military host, perhaps due to economic constraints. Foodstuff and basic goods would have to be provided by the provinces nearer Egypt, that is, of the Outremer, and thus the Catepan of Syria, Andronikos Dalassenos Rogerios, was entrusted with the task of procuring adequate resources from among the Franks and from Cyprus and the Syrian provinces.

In an effort to cut expenditures, Manuel had disbanded a part of the imperial navy a few years after the war against Sicily, having paid the mariners and sailors not with stipend, but rather with the booty sacked from Apulia, leaving the better part of the armada operative solely in the Aegean and in the southern littoral of Anatolia. To compensate the diminishment of seapower, he reinstated the treaties of alliance with the Republics of Ancona and Ragusa, who received new harbors in the Black Sea to exploit the tangents of the lucrative Silk Road, as well as with Venice, who received the island of Karpatos as a concession. In any case, adopting the same strategy of dividing the larger army so as to facilitate logistical supply, Manuel ordered the divisions originating from Europe to be gathered in Adrianople, and then to be transported by sea to Antioch, where they would proceed overland across the Outremer into the Sinai, while a second military force, comprising mostly those levied from Asia, such as the Armenians and the Turkomans, would be constituted in Sebasteia and from there they would traverse into Syria across the Taurus range.

Predictably, the decision to impose the burdens of the logistical network upon the Frankish-ruled provinces of Palestine and Syria, both of whom produced little surplus to sustain a massive army for a long period of time, would prove to be a poorly-conceived one, and from the very beginning of the campaign Manuel’s army was faced with operational shortcomings and lack of adequate supplies. This, in turn, exacerbated the already existing ill-sentiments between the Levantine Franks and the Rhõmaîoi - the former because they felt genuinely humiliated by a foreign empire, and the latter because they believed that the Franks were unreliable and insidious coadjutors - which grew particularly noticeable after the middle of summer of 1174 A.D., when Manuel’s army arrived in Caesarea.

The expeditionary army only passed through Palestine, but the Basileus briefly detoured to visit Jerusalem, where he interviewed with Archbishop Walter, at the time sickened by malaria, and with the nobles of the Court of Grandees, who assembled in the Holy City in the tepid days of August. The Basileus barely disguised his indignation, expressed with glacial demeanor and haughty language, when he found out that the Duke of Galilee had only mustered less than half of the numbers he had demanded of knights, soldiers and levies; the paramount aristocrats of the realm, saw themselves forced to prostrate and humiliate themselves to placate the Emperor. It appears that, in this event, the one that garnered the Emperor’s goodwill was none other than Duke Robert of Emèse, whose tactful finesse convinced the Rhõmaîon autocrat that the land had been reaped of brave souls by the recent wars, but many others were to be given to the cause of Christ. At the time, Emèse was hosting the illustrious presence of the French Duke Hugh III of Burgundy and his uncle, Count Stephen of Sancerre, both of whom were trusted advisors in the Parisian court, and the fact that Robert convinced them to join the war in Egypt, thus contributing with thirty knights to the cause, certainly elevated Manuel’s opinion of him and of the French princes [10].

From Palestine they marched into the Sinai by the way of Larizis [OTL El-’Arish], whose actual settlement had become underpopulated over the decades, but had long since been retained in Frankish hands by the Templarians, who operated the famous fortress of Saint Andrew.

One document of the period, which did not survive to our days, but is mentioned in the sources, is a letter from the Lateran Palace to Manuel, in which Pope Sylvester IV forwards a series of complaints from Archbishop Walter of Jerusalem regarding the misbehavior of the Greek army in the Holy Land, and their greediness and rapacity, which offended the pious Christians and thwarted the venture of countless pilgrims in these years. John Kinnamos, who at the time was serving in the Emperor’s administrative-in-march retinue, mentions that Manuel would receive the missive while operating in Egypt, and that he scoffed at its declarations, remarking that he would soon be the master of Egypt and the restorer of the true faith in the land of Saint Athanasius the Great. In any event, this serves to demonstrate that, for all the cordiality between the Rhõmaîon Emperor and the Patriarchate of Rome, their diplomatic relation had been strained due to Manuel’s domineering policy towards the Frankish Outremer.

III. Of the Campaigns in Damietta and Bilbeis and the March to Cairo

Upon entering the Sinai, the soldiers were expected to live off the land and to acquire the resources by the assistance of collaborative communities or by force from unwilling ones.

The first strike against the Fāṭimids was directed against Farama, another settlement that, much like Larizis in the Sinai, had suffered through the various decades of warfare between Egypt and the Franks and Rhõmaîoi, and had thus become mostly depopulated. It had been repurposed by al-Malik al-Ghazi as a fortress, with new battlements and towers, but, in the end, it was an ineffectual defense against the invaders, because the garrison, comprised mostly by Bedouin and Sudanese soldiers, had deserted after the Vizier’s deposition. Having secured a harbor-town and fortress, the Christian army now could be replenished by sea, but a series of storms shipwrecked flotilla of victuals coming from Cyprus in November, and their numbers were too large for them to survive off the nearby lands, so Manuel left a small garrison and marched almost immediately, hoping to reduce Damietta before the arrival of winter.

And this they did; the city fell after a week long siege, after which the city was sacked and its garrison soldiers slain to the last man. It had barely recovered the casualties and structural damages suffered in the previous war, in which it saw through two destructive sieges, and now saw its civilian population, comprised mostly by Muslim Saracens and Jews, submitted wholly into slavery; as per usual, Copts were spared, but they could scantily provide adequate food, goods and utensils to thousands of ravenous warriors. The situation worsened severely after Manuel decided to interrupt campaign and winter in the region; while he disbanded some levies, most of the mercenaries were quartered, and they, all too alien in language and customs, routinely preyed upon the hapless Coptic communities of the region, and regularly harassed the Saracen ones. By the next spring, the surviving Copts had become noticeably impoverished without any sort of compensation to the acts of violence.

Al-Malik al-Ghazi had wrested from the new Caliphal government the rich provinces of the Delta, and became entrenched with his loyal army of Mamluks and recruited Bedouins in Alexandria. He had thus to protect his diminished domain from the Christian invaders, and prepared for a counteroffensive, but was then surprised by the coming of an embassy from Manuel, who, aware about the situation, offered an armistice. In spite of their bitter enmity and of his particular hatred towards the Turkic freedman who had defeated him years before, the Basileus knew that at the time al-Malik was weakened and could not hope to impede the advance of the Christian army; he could, however, harass it and jeopardize their supply network over the Sinai, or, if Manuel advanced into the interior, he could attempt to conquer Damietta, thus cutting off their retreat. Recognizing him as the lesser evil, then, Manuel preferred to appease the Mamluks, and to focus his offensive against Cairo. Al-Malik al-Ghazi delayed negotiations until the opening months of spring in 1175 A.D., perhaps to assess the situation better, but then, once he heard of the assembling of a Caliphal army in Bilbeis, he conceded with Manuel’s offer, likely hoping that both his enemies would bleed themselves to death.

John Kinnamos describes Manuel’s stratagem to surprise and defeat the Saracens: Until the midst of 1175 A.D., the Rhõmaîoi (encompassing the various associated races, from the Cumans to the Armenians) constructed a series of palisades, towers and forts apparently to protect Damietta and the occupied areas in the shores of the Phatnitic lake [11], thus causing the impression that they would adopt a defensive position and await for the coming of the Caliphal army to oust them. This was, however, a deception. As soon as the notice came to Manuel from the approach of a Saracen army from Bilbeis, the Christian army went back to Farama/Pelusium, ferried by sea, and then they marched westward along the shore of the Phatnitic lake, and thus assaulted the Saracens from their rearguard while they prepared to attack the fortifications near Damietta. The strategy was well-conceived, but the execution was marred by poor coordination between the segments of the army; many of the mercenary groups, such as the Cumans and the Turkomans, broke ranks and attacked without awaiting for the coming of the infantry army, and this in turn created confusion when they came back, maneuvering with their customary feigned retreat, which paralyzed the confused Frankish horsemen. All this debacle did not deter the more experienced and battle-readied Christian army from obtaining a clear victory, but it, as per the report of John Kinnamos, might have perhaps frustrated the decisive triumph that Manuel expected. Indeed, broken divisions of the Sudanese and the Armenians managed to retreat to Xois, and the Basileus opted to not pursue them, fearful that al-Malik al-Ghazi could betray the agreement and attack Damietta from his behind, considering that Alexandria was but a couple days’ march away. On the other hand, Manuel was not keen on marching against Alexandria himself at the time being, it was very much well defended and the deposed Vizier was a formidable warmonger and charismatic leader.

Parleys were initiated with Vizier Husayn ibn Abu ʾl-Hayjā to exchange prisoners and collect ransom, and the Caliphal embassy attempted to secure a five-year truce in exchange for tribute and exorbitant payments. The Basileus outright refused, and demanded the unconditional capitulation of the Caliphate. Some of his subordinates, however, from among the Franks and the Armenians, led by Thomas of Tarsus [12], vehemently opposed his decision, arguing that they had provided the due service to their liege and demanded immediate reward in money and in kind. Realizing that together they had enough strength to bargain, the Franks and the Armenians threatened to mutiny and to break off the army, forcing Manuel, all too needful of manpower, to compromise. They accepted the promise of a larger share of booty in the following acts of the campaign, but the debacle severely undermined Manuel’s authority and demonstrated how relatively easy it was to sustain insubordination in a multi-ethnic and unloyal army. In any event, Manuel did not seriously ponder ending the war without obtaining, in the very least, a formal recognition of Constantinopolitan supremacy in regards to Egypt.

******

Notwithstanding the brief paralysis of the campaign by virtue of the diplomatic talks with the Caliphate and of the insubordination of segments of his army, Manuel did not stop the preparations for the upcoming maneuver; while in Damietta, the soldiers received much needed replenishment of goods and workforce by sea, transported by Anconitan and Venetian ships. John Kinnamos records that, until that moment, the army’s horses had become somewhat scarce, hundreds of them having perished to disease and undernourishment, and that Cumans, Turks and Franks fought one another in the very encampment to dispute the remaining mounts.

Thence, the army was on the move again in late 1175 A.D.

Manuel opted for a risky strategy. The Christian army remained inactive, stationed in the region between Damietta and Farama, during the whole of autumn, receiving replenishment and distributing payment and resources to the soldiery, and awaited precisely for the coming of winter to march again. They had, more than once, operated during winter season in the war of 1163-1166 A.D., and were aware that, while the Egyptian climate became particularly cold and rainy, especially during December and January, it was far less of inhospitable if compared to the European and Anatolian climes. But Manuel was especially concerned about acquisition of food: he knew that Egypt usually produced agricultural surpluses, especially in the regions of the Delta and of the Nile course, and that the villages and provincial administrations kept and and preserve foodstuff during winter in granaries and quarters. The Basileus then intended for the army to live off the land during the remainder of the operations, occupying and exploiting these depots in detriment of the local communities. The risks would increase significantly if the army became bogged down in siege operations or if the enemy prevented their access to these warehouses, the result being that they would likely starve.

Despite the existing precedents of the previous conflict, the Fāṭimids were apparently surprised by the fact that the Rhõmaîoi host did not disband in winter and that it in fact marched to Cairo. The consistent raining diminished their combat readiness, but Manuel pressed for them to march. The Egyptians resorted to opening the dams to flood the Nile, but the expedient, which had been successful so many times before in the previous centuries, failed because, during the height of winter, the waters of the Nile had shrunk significantly and did not deter Manuel's march. In the span of a couple days, they were mounting the camp near Bilbeis and encircled the fortified city.

The Rhõmaîoi were not willing to await and starve the defenders into surrender. They would soon be lacking in resources and the Vizier was already mustering the forces of the Rayhāniyya and Juyūshiyya and conscripting levies from Fustat and the other cities to face the Christian threat. Over the course of four other days, the Christian warriors threw themselves against the walls, against the towers and battlements, using ladders, battering rams and trebuchets, and took the city by storm once they defeated the numerous defenders. The price in human lives was heavy for both sides; John Kinnamos estimates the casualties of the Christians in a couple thousands - from an army that certainly numbered, even in an optimistic estimate, below ten thousand men -, and describes the massacre of the Muslim citizens that followed the capture of the settlement. The plundering of their goods and houses was particularly violent and, despite Manuel’s best efforts, it was not even restricted to the Saracens; the sources mention wanton slaughter, arson, torture, rape and other atrocities against both Muslims and Coptic Christians; even if the latter were under imperial protection, there was only so much the Rhõmaîon soldiers could do to prevent the curb of the insubordinate Cumans, Turks and even Franks. To those that were indeed spared, their fate was hardly fortunate in any case: they were evicted from their houses so as to give quarter to the invading soldiers as they prepared to march against Cairo; they were left with scarcely any food during the height of winter and, worse even, many of them were contaminated by the infectious fever sickness that was afflicting the marching men-at-arms.

It seems, indeed, that the most populous and urbanized regions of Egypt at the time were struggling with a devastating epidemic, likely of camp fever, disseminated by the almost interrupt movements of armies, from the Berbers to Bedouins, and from the Sudanese to the foreign Christian invaders. The spread of the disease in the Nile metropolises and in the Mediterranean region of Egypt between 1170 and 1175 A.D. exacted a significant number of casualties among the Egyptian population, especially the urban ones, already afflicted by the overcrowding resultant of the devastation of the northeastern Delta and of the western reaches, and thus also eventually by scarcity of staples.

The chronic incapacity of the Caliphal government to respond to these Biblical-scale calamities during the second Rhõmaîon invasion, perhaps excepting in Fustat and Cairo, where it still exerted absolute rule, inspired as consequence the rebellion of other provincial governors, especially in Upper Egypt, such as from the Banu Kanz, who still held significant influence in the administrative region orbiting Aswan. They were after all, left to their own devices anyway, and wholly despised the moribund Vizierate dominated by palatine eunuchs. In the provinces of Gizeh and Sharqia, fearing the atrocious campaigning of the Rhõmaîoi, the local sheiks proclaimed allegiance to al-Malik al-Ghazi, who still preserved a figment of stability and defensive military consistency in the northwestern region of Egypt and in Cyrenaica, whose main cities, from Tobruk to Berenice, had been garrisoned by loyal Mamluks.

Manuel himself was struck by the illness, according to John Kinnamos report, in January 1176 A.D., but the Rhõmaîon leadership withheld this information from the soldiery, fearing that the physical weakness of the monarch would inspire another wave of insubordination, which, coupled with the alarming spread of the epidemics among them, both of camp fever and of black entrails [i.e. dysentery]. However, Manuel’s stubbornness might have precipitated his own undoing. Suffering with hemorrhagic fever, the brave and insensate Basileus persisted in the march, and refused to be carried in litter or to rest in his tent for little more than a couple days, even while the army struggled through the cold nights of January. The exertions undermined his health, however, and the mild symptoms soon evolved to a far more grave condition. The Emperor, who was well-versed in medicinal knowledge, having read the works of Hippocrates and Galen [13], disputed with his own physicians and advisors about the adequate treatment for his illness, believing to be suffering with malaria. Whatever might have been the nature of the disease, the fact remained that Manuel’s body, aged almost sixty years old, tired by the exertions of military life, and also shivering in the cold nights, did not provide the necessary immune response, and thus, by the very last day of January 1176 A.D., he perished at last, secluded in his pavilion in the siege camp facing the walls of Cairo.

In the next chapter: the consequences of Manuel's death for the Romans, and the effects of the Roman defeat in Egypt to the Fatimids and to the Franks.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Footnotes:

[1] Hafs ibn Yahya is the progenitor of the Hafsid dynasty that ruled Ifriqiya between the early 13th C. and the late 16th C.

[2] “Sūdānī” is the Arabic word referring to black Africans, which might or not be actually Sub-Saharan. I opted to use the Arabic word because it is more comprehensive than the modern-English term “Sudanese”, encompassing the Nubians, the Ethiopians and peoples under the sphere of the Kanem-Bornu empire.

[3] This serves to demonstrate, even if in a short summary, how long and protracted was the decline of the historical Fatimid Caliphate, whose ethnic-based military divisions did more harm than good due to intense factionalism. In retrospect, and with hindsight, it also explains how and why the (first) Crusaders were so amazingly successful once they occupied Jerusalem and consolidated their hold in Palestine wholly unimpeded from Fatimid retaliation until the establishment of the Ayyubids under Saladin. The Fatimid state simply lacked the necessary political energy to counter Frankish expansionism at the time.

[4] Nasir al-Dawla ibn Hamdan played a leading role in the civil war of 1067 to 1073 between the Fatimids' Turkish and Nubian troops as the leader of the former. In this struggle, he requested the assistance of the Seljuks and even tried to abolish the Fatimid caliph al-Mustansir and restore allegiance to the Abbasids. He succeeded in becoming master of Cairo and reduced al-Mustansir to a powerless puppet, while his Turks plundered the palace and the treasury. His rule was ended with the murder of himself and his family in March/April 1073. The anarchic conditions in the country continued until al-Mustansir called upon the governor of Palestine, Badr al-Jamali, for aid in late 1073.

[5] Maimonides is such a fascinating and relevant historical character that I couldn’t go without at least mentioning him, and there’s an interesting butterfly here: IOTL, he went in exile from Morocco to Egypt, in the very last years of the Fatimid Caliphate, and witnessed its usurpation by Saladin and the formation of the Ayyubid Sultanate, and eventually became the Nagid of the Egyptian Jewry. ITTL, due to the complicated domestic situation in Egypt, Maimonides will go elsewhere. I intend to write a specific chapter addressing the Jewish communities and major Jewish figures of the period..

[6] Andronikos Komnenos, IOTL, was discovered implicated in a plot against Emperor Manuel and remained in prison for almost ten years, before escaping in 1165. He then went to the court of his cousin Yaroslav in Galicia, but soon reconciled with the Emperor and returned to Constantinople, only to a few years later be exiled once again. ITTL, his first exile occurs exactly like OTL, but upon his return to the imperial court, he becomes much more influential to a more psychologically distressed Manuel than IOTL.

[7] Béla III IOTL was for a considerable period Manuel’s heir apparent, with the name of Alexios, and was betrothed to Manuel’s daughter Maria Porphyrogenneta. After Manuel’s son Alexios was born, Béla was “removed” from his political positions, but later on became King of Hungary, one with a mixed relationship with the last Komnenoi emperors. ITTL Manuel had a different marriage [see Chapter 59, Section II] and produced three male sons far earlier than IOTL, and thus Béla never became heir designated, but instead remained as an active member of the Byzantine court, and the nuptials to Manuel’s daughter were effectively concluded so as to secure the alliance with Hungary. This will have interesting divergences down the road, because Maria will never marry into the Italian House of Montferrat, while Béla himself will have a different set of progeny, even if we’ll see the birth of his first son Emeric, who has been previously mentioned in the TL [see Interlude 4 (Part III)].

[8] IOTL, during this timeframe, Stefan Nemanja was a fairly loyal vassal of the Empire; he even participated in the campaign of Myriokephalon which resulted in a tactical Byzantine defeat, so I figured it would make sense, here, for him to participate in the Egyptian campaign instead.

[9] The situation of the Anatolian Turkomans will be addressed in better detail in Chapters 67 and 68.

[10] Stephen of Sancerre and Hugh III of Burgundy did historically go to the Holy Land in this timeframe (1170 or 1171), with the latter being considered by OTL King Amalric as a possible suitor for his daughter Sibylla (the same who later married Guy of Lusignan). In this counterfactual TL, they go to the Outremer as pilgrims, and not properly as Crusaders, so they are more illustrious guests than commanders of an army.

[11] Modern Lake Manzala. I’m not sure if it did exist during the Middle Ages, or if it is resultant of the Suez Canal, but there are various historical salt-water lakes in the northeastern region of Egypt, so I went for it.

[12] The historical ruler of Cilician Armenia in this timeframe was Mleh, but considering that he rose to power in a coup, whose very occurrence is butterflied ITTL. Here, the deposed and executed Ruben II of Armenia, son of Thoros II, rules from 1169 without interruption, but in 1174 he was still a child, and thus the representative of the Cilician Armenians is the duchy’s regent, Thomas. Thomas himself is a very obscure individual of whom we only know the first name, so I invented his reference as being from Tarsus, which at the time was one of the largest Cilician cities.

[13] Manuel being knowledgeable in Medicine is factual. IOTL, during the Second Crusade, he himself treated Emperor Conrad of the HRE and King Baldwin III when they fell ill.

Commentary: