You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Alternate Wikipedia Infoboxes VII (Do Not Post Current Politics or Political Figures Here)

- Thread starter BigVic

- Start date

How did he live to 130 and how was he capable of running for and being in office well into his 100's?

Gold lovers GTFO, Silverite patriots are in CONTROL!

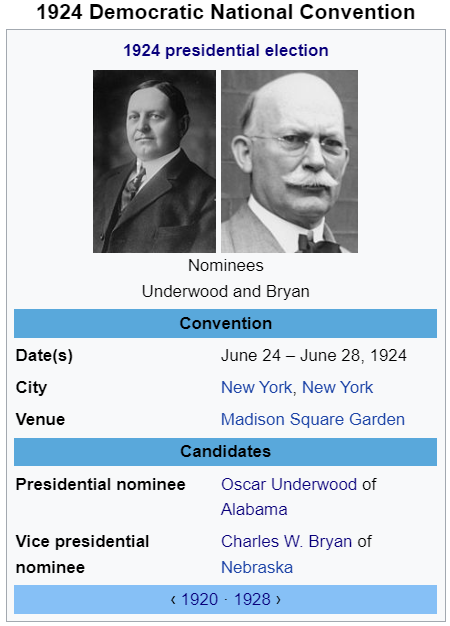

Bargaining With the Devil: The 1924 DNC

Oscar Underwood smiled as he read the telegram from President Harding. He'd won. He would be president. It was time to build a Cabinet. The nice part, he supposed, was that a lot of it had been determined a few months earlier at the DNC, so there was less to think about than there otherwise might have been. The 1924 Democratic National Convention was, at its heart, the story of a narrowly averted disaster. We are familiar of the story of our world, of a convention that went on for an ungodly 103 ballots before finally making John W. Davis the king of a deeply divided party. But this is not that story - this convention lasted just four ballots.

This was enabled mostly because Warren G. Harding's heart attack ended up not being fatal. The president survived, and with his survival came continued scrutiny of the Teapot Dome scandal. Most Democrats were benefitted by this scandal, as it would hurt the Republican Party, and therefore boost their chances of reelection. And all politicians like being reelected. But there was one for whom the scandal was quite the opposite - one William Gibbs McAdoo, who was found to have accepted a donation from Edward L. Doheny, the man accused of bribing Secretary Fall. Once the frontrunner for the Democratic nomination, McAdoo was haunted by the specter of the donation, even though no one ever offered a more serious accusation. As the 1924 Democratic presidential primaries progressed, Oscar Underwood's once-doomed campaign was brought back to life by the scandal. An anti-KKK wet, Underwood was simply out of step with the Democratic Parties of the South. But many were convinced McAdoo could not win the general election. Or simply found McAdoo distasteful. Whatever the reason, Underwood got a nice chunk of delegates from the South, and his campaign remained alive.

This didn't knock out McAdoo, however. His chumminess with the KKK was divisive, but got him the support of a chunk of voters who became McAdoo's bedrock, unwilling to consider a wet like Underwood or, even worse, a wet Catholic like Al Smith. Underwood surviving helped him get another chunk of voters in the Northern primaries who didn't want Smith, but were leery of outright associating with the Klan or thought McAdoo was corrupt. John Davis sandbagged him a bit by competing for these same voters, but Underwood persisted. As the Convention opened, these primaries and closed caucuses had gotten him to a third place in the Convention, and made him almost a lab-grown, "leave everyone unhappy" compromise candidate. He masterminded a motion to put a plank on the party platform denouncing the Klan, which very narrowly passed - a major setback for the McAdoo campaign.

When the presidential balloting began, McAdoo took first place with 282.5 delegates, to Smith's 221 and Underwood's 211.5 (alongside a smattering of favorite sons). This would be the former Treasury Secretary's height of support. After the first ballot, Underwood met with John W. Davis, and after the meeting Davis agreed to endorse him; James Cox, the party's failed 1920 nominee who had received 59 delegates, also endorsed Underwood. Their combined 90 delegates largely went to Underwood on the second ballot, who additionally began to take some of McAdoo's supporters and won over the Louisiana delegation, as the ballot went 330 for Underwood, 277 for McAdoo, and 237 for Smith (who also lost some support to Underwood, but made it up by claiming the delegates of New Jersey favorite son Governor George Silzer). On the third ballot the stampede began; Underwood took the favorite sons' delegates and had won a majority, and everyone knew he would be the compromise nominee. It would take an additional ballot for him to exceed the two-thirds majority required, and meeting with McAdoo and Smith privately, but he had taken the nomination.

When Underwood was elected president, among his Cabinet choices were John W. Davis for Secretary of State, William Gibbs McAdoo for a second stint at the Treasury Department, and former Assistant Secretary of the Navy, 1920 vice-presidential nominee, and Smith ally Franklin D. Roosevelt for Secretary of War.

Oscar Underwood smiled as he read the telegram from President Harding. He'd won. He would be president. It was time to build a Cabinet. The nice part, he supposed, was that a lot of it had been determined a few months earlier at the DNC, so there was less to think about than there otherwise might have been. The 1924 Democratic National Convention was, at its heart, the story of a narrowly averted disaster. We are familiar of the story of our world, of a convention that went on for an ungodly 103 ballots before finally making John W. Davis the king of a deeply divided party. But this is not that story - this convention lasted just four ballots.

This was enabled mostly because Warren G. Harding's heart attack ended up not being fatal. The president survived, and with his survival came continued scrutiny of the Teapot Dome scandal. Most Democrats were benefitted by this scandal, as it would hurt the Republican Party, and therefore boost their chances of reelection. And all politicians like being reelected. But there was one for whom the scandal was quite the opposite - one William Gibbs McAdoo, who was found to have accepted a donation from Edward L. Doheny, the man accused of bribing Secretary Fall. Once the frontrunner for the Democratic nomination, McAdoo was haunted by the specter of the donation, even though no one ever offered a more serious accusation. As the 1924 Democratic presidential primaries progressed, Oscar Underwood's once-doomed campaign was brought back to life by the scandal. An anti-KKK wet, Underwood was simply out of step with the Democratic Parties of the South. But many were convinced McAdoo could not win the general election. Or simply found McAdoo distasteful. Whatever the reason, Underwood got a nice chunk of delegates from the South, and his campaign remained alive.

This didn't knock out McAdoo, however. His chumminess with the KKK was divisive, but got him the support of a chunk of voters who became McAdoo's bedrock, unwilling to consider a wet like Underwood or, even worse, a wet Catholic like Al Smith. Underwood surviving helped him get another chunk of voters in the Northern primaries who didn't want Smith, but were leery of outright associating with the Klan or thought McAdoo was corrupt. John Davis sandbagged him a bit by competing for these same voters, but Underwood persisted. As the Convention opened, these primaries and closed caucuses had gotten him to a third place in the Convention, and made him almost a lab-grown, "leave everyone unhappy" compromise candidate. He masterminded a motion to put a plank on the party platform denouncing the Klan, which very narrowly passed - a major setback for the McAdoo campaign.

When the presidential balloting began, McAdoo took first place with 282.5 delegates, to Smith's 221 and Underwood's 211.5 (alongside a smattering of favorite sons). This would be the former Treasury Secretary's height of support. After the first ballot, Underwood met with John W. Davis, and after the meeting Davis agreed to endorse him; James Cox, the party's failed 1920 nominee who had received 59 delegates, also endorsed Underwood. Their combined 90 delegates largely went to Underwood on the second ballot, who additionally began to take some of McAdoo's supporters and won over the Louisiana delegation, as the ballot went 330 for Underwood, 277 for McAdoo, and 237 for Smith (who also lost some support to Underwood, but made it up by claiming the delegates of New Jersey favorite son Governor George Silzer). On the third ballot the stampede began; Underwood took the favorite sons' delegates and had won a majority, and everyone knew he would be the compromise nominee. It would take an additional ballot for him to exceed the two-thirds majority required, and meeting with McAdoo and Smith privately, but he had taken the nomination.

When Underwood was elected president, among his Cabinet choices were John W. Davis for Secretary of State, William Gibbs McAdoo for a second stint at the Treasury Department, and former Assistant Secretary of the Navy, 1920 vice-presidential nominee, and Smith ally Franklin D. Roosevelt for Secretary of War.

He just refused to die and at some point everyone got used to it.How did he live to 130 and how was he capable of running for and being in office well into his 100's?

Is he the worlds oldest living human at this point?He just refused to die and at some point everyone got used to it.

I meant 163 hereHow did he live to 130 and how was he capable of running for and being in office well into his 100's?

Did Nanjing get atomised?View attachment 888793

same tl as last one, rip bozo

I take that Robert Taft and McCarthy were both Prez in this timeline.He led treasonous opposition to the Taft and McCarthy Administrations

he got captured and shotDid Nanjing get atomised?

From the same wacky timeline as my previous post.

Sportacus (Wellowan: Íþróttaálfurinn: born November 10th, 1994) is a Wellowan Public Health Advocate, Entrepreneur, and Politician currently serving as the 8th President of Wellow.

Sportacus's career began in his home town of Latibær. During his childhood, the town was full of pollution and smog as a result of de-industrialization in Wellow. This led to the citizens adopting unhealthy lifestyles, and life expectancy plummeting across both the town and the nation as a whole. This would inspire Sportacus, who would devote his life to fixing this issue in his homeland.

After spending his first adult years founding various healthy eating establishments and making a name for himself in his hometown, he would run for mayor in 2010. In an upset, he would defeat Nenni Níski by a total of around 2,000 votes. During his 11 years as mayor, he would transform Latibær from a run down rusting town into a healthy, booming city with some of the best life expectancy in the country. By the dawn of the 2020s, he had his sights set on the highest office in land.

The chaos of the Merge severely undermined the popularity of President Milford Meanswell. Taking advantage of this, Sportacus would win a landslide victory in the 2021 Wellowan Presidential election. Taking office in a time of chaos, Sportacus would successfully implement his policies of healthy eating and economic revivalism across his country, leading to a boom in Wellowan finance and culture. In foreign policy, he would pursue a neutral stance in most major world issues, with the exception of a denouncing the Larry Foulke regime during the Second Belkan War.

Through his work in reviving Wellow from its economic decline, and creating one of the healthiest populations in the world, Sportacus has become an icon for health advocates across all of the worlds. His reputation remains stellar and his rule widely popular, despite various challenges to his rule from reactionary leader Robbie Rotten.

Sportacus (Wellowan: Íþróttaálfurinn: born November 10th, 1994) is a Wellowan Public Health Advocate, Entrepreneur, and Politician currently serving as the 8th President of Wellow.

Sportacus's career began in his home town of Latibær. During his childhood, the town was full of pollution and smog as a result of de-industrialization in Wellow. This led to the citizens adopting unhealthy lifestyles, and life expectancy plummeting across both the town and the nation as a whole. This would inspire Sportacus, who would devote his life to fixing this issue in his homeland.

After spending his first adult years founding various healthy eating establishments and making a name for himself in his hometown, he would run for mayor in 2010. In an upset, he would defeat Nenni Níski by a total of around 2,000 votes. During his 11 years as mayor, he would transform Latibær from a run down rusting town into a healthy, booming city with some of the best life expectancy in the country. By the dawn of the 2020s, he had his sights set on the highest office in land.

The chaos of the Merge severely undermined the popularity of President Milford Meanswell. Taking advantage of this, Sportacus would win a landslide victory in the 2021 Wellowan Presidential election. Taking office in a time of chaos, Sportacus would successfully implement his policies of healthy eating and economic revivalism across his country, leading to a boom in Wellowan finance and culture. In foreign policy, he would pursue a neutral stance in most major world issues, with the exception of a denouncing the Larry Foulke regime during the Second Belkan War.

Through his work in reviving Wellow from its economic decline, and creating one of the healthiest populations in the world, Sportacus has become an icon for health advocates across all of the worlds. His reputation remains stellar and his rule widely popular, despite various challenges to his rule from reactionary leader Robbie Rotten.

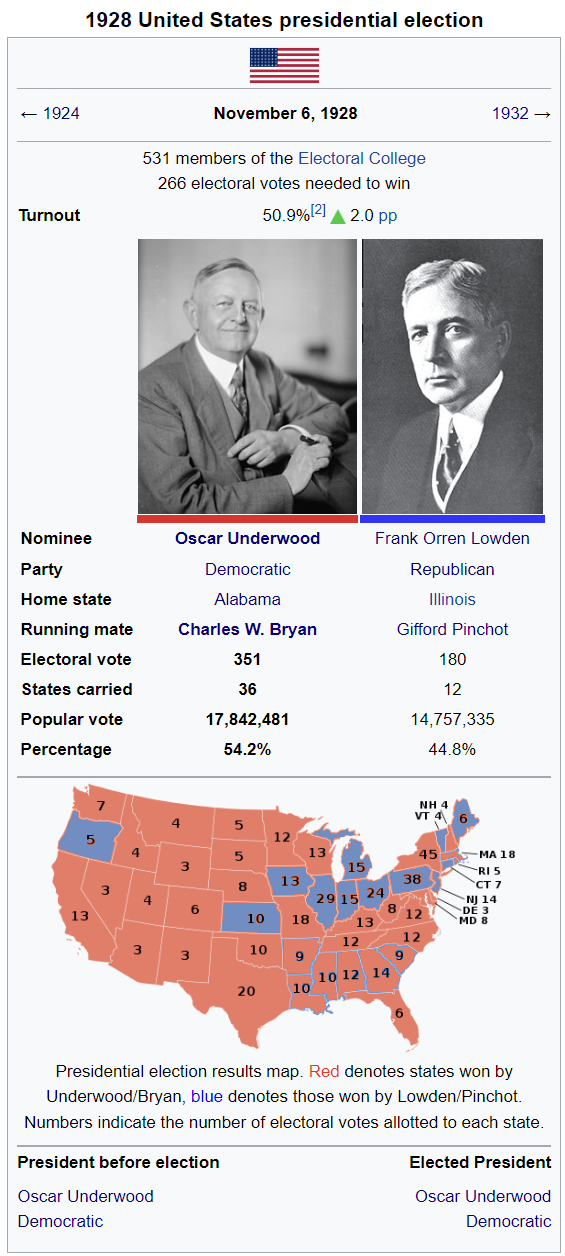

Bargaining With the Devil: When They Go Lowden

If Oscar Underwood was the unhappy compromise that could, then Frank Orren Lowden was the unhappy compromise that couldn't. The Republican Party stood in disbelief at the result. Oscar Underwood had just won 54% of the vote; no Democrat since Jackson had exceeded 51%, and only Van Buren, Pierce, and Tilden, the last of whom had run in 1876, had won a majority at all. Here they stood, the Republican Party's place as the natural party of governance seemingly shattered.

Finger-pointing began immediately. Many said that the economic prosperity of the decade had helped Underwood, and Republicans' attempts at claiming credit for it only reminded people of Warren Harding's unsavory presidency. Others said Lowden ran a bad campaign, that he had failed to distinguish himself sufficiently from Underwood on any issue other than Prohibition (and there, was still advocating for retaining the status quo) and so, when voters were faced with two seemingly identical candidates, many chose the incumbent over the challenger who promised no change. The reality was belied by the finger-pointing: the truth was, the Republican Party was divided. Perhaps had they been in power these differences between progressives and conservatives that seemed to have no end might have been papered over (though, as the 1923 speakership fight had shown, that was by no means a guarantee), but in opposition the two factions brought out the knives and ended up shivving each other - to the Democrats' benefit.

The big thing that had caused the fight this time was the Farm Relief Act of 1927. Many had noticed the prosperity of the Roaring Twenties hadn't spread to farmers, who were dealing with an economic calamity in the form of the Dust Bowl. Underwood's conservative government had been broadly similar to Harding's in many ways, though not quite so aggressively laissez-faire, as Underwood felt more of a need to sate the progressive wing of his party, but the Farm Relief Act had transpired anyways. Part of it was that conservative forces were not as against it as they were other interventionist programs - indeed, several key sponsors of the act included conservative prairie Republicans like Charles McNary - but also the reality of the Farmer-Laborites.

Born as the primary opposition to the Republicans in Minnesota, where the state Democratic Party never recovered its pre-statehood dominance, the Farmer-Labor Party had their first taste of power in the Underwood administration when the 1924 election shook out a Senate composed of 47 Democrats, 47 Republicans, and their 2 Minnesota seats; thus, they held the balance of power in the chamber, and they made sure the Democrats paid them their dues when they wanted legislation through the Senate. The 1926 elections saw this Senate dynamic go away when the Democrats took advantage of an overexposed Republican class from the 1920 landslide to actually gain several seats and the Senate majority, but the Farmer-Laborites gained something far more valuable: the balance of power in the House, where the Democrats retained a plurality but were denied an outright majority. That required an actual coalition to be negotiated in order to elect a speaker, and with calls for farm relief already on the rise since 1924, the Farmer-Laborites made their move.

This once again exposed the divisions of the Republican Party. Conservatives who didn't represent Western seats that knew the pain of the Dust Bowl were rather hostile to the idea, while Progressives, like former Agriculture Secretary Henry C. Wallace's son Henry A. Wallace, were more open to it. When the 1928 RNC convened, it was the key dividing line between the two strongest candidates, Lowden and former Commerce Secretary turned California Governor Herbert Hoover: Hoover, in theory the more "progressive" candidate, was actually against the Farm Relief Act, and advocated instead a plan based around modernization, electrification, and tariffs, as well as a farm board, while Lowden, though more conservative, was in favor of the passed Act. In a bitter convention, the Lowden forces scored a victory when the delegates approved platform plank in favor of the act. This took the wind out of the Hoover campaign and enabled Lowden to win the nomination. But it had been at a cost. The party had been deeply divided both pro-relief vs. anti-relief and progressive vs. conservative lines, and almost everyone in the party had a reason to differed with Lowden on at least one of the lines. Meanwhile, the party platform being pro-relief made it very pro-status quo; indeed, many claimed that the only real difference between Lowden and Underwood was that the former was a dry and the latter a wet, and the only reason no third-party emerged was because Fighting Bob had died in 1925 and no one had yet taken up his mantle. The choice of Gifford Pinchot for the vice-presidency was intended to balance the ticket with a progressive, but many had already decided they were sitting this one out because they just didn't like Lowden, and alienated anti-farm relief conservatives, who ended up also staying home. Charles G. Dawes, a former Harding administration official who had been the early favorite for the vice-presidential nomination, would have been more unifying, but was, like Lowden, an Illinoisian, and so the possibility of constitutional issues over Illinois' electoral votes in the case of a close election precluded his selection; an offer to Hoover was rejected when Lowden refused to countenance the opposite move.

In the end, turnout was only barely higher than 1924's, and arguably only because that election's turnout had already been absurdly low. The results showed danger in other areas, too: Underwood proved his wins in New York, New Hampshire, and Rhode Island four years prior hadn't been flukes by narrowly winning all three and flipping Massachusetts. Many noticed the prodigious influence of Al Smith in turning out Catholics, perhaps in preparation of a presidential bid of his own in four years. But there was a traditionally Democratic demographic Republicans had hoped to compete for in the aftermath of the 1920 result firmly back in their camp for two elections, and which now seemed to making the once-moribund Democratic Parties of the Northeast the vice-president's brother had decimated viable once again. Wisconsin and Minnesota seemed to have flipped as much because of them as because of the Farmer-Laborites' low-key cooperation.

The Republicans were quickly becoming a desperate animal. And there's few things more dangerous.

If Oscar Underwood was the unhappy compromise that could, then Frank Orren Lowden was the unhappy compromise that couldn't. The Republican Party stood in disbelief at the result. Oscar Underwood had just won 54% of the vote; no Democrat since Jackson had exceeded 51%, and only Van Buren, Pierce, and Tilden, the last of whom had run in 1876, had won a majority at all. Here they stood, the Republican Party's place as the natural party of governance seemingly shattered.

Finger-pointing began immediately. Many said that the economic prosperity of the decade had helped Underwood, and Republicans' attempts at claiming credit for it only reminded people of Warren Harding's unsavory presidency. Others said Lowden ran a bad campaign, that he had failed to distinguish himself sufficiently from Underwood on any issue other than Prohibition (and there, was still advocating for retaining the status quo) and so, when voters were faced with two seemingly identical candidates, many chose the incumbent over the challenger who promised no change. The reality was belied by the finger-pointing: the truth was, the Republican Party was divided. Perhaps had they been in power these differences between progressives and conservatives that seemed to have no end might have been papered over (though, as the 1923 speakership fight had shown, that was by no means a guarantee), but in opposition the two factions brought out the knives and ended up shivving each other - to the Democrats' benefit.

The big thing that had caused the fight this time was the Farm Relief Act of 1927. Many had noticed the prosperity of the Roaring Twenties hadn't spread to farmers, who were dealing with an economic calamity in the form of the Dust Bowl. Underwood's conservative government had been broadly similar to Harding's in many ways, though not quite so aggressively laissez-faire, as Underwood felt more of a need to sate the progressive wing of his party, but the Farm Relief Act had transpired anyways. Part of it was that conservative forces were not as against it as they were other interventionist programs - indeed, several key sponsors of the act included conservative prairie Republicans like Charles McNary - but also the reality of the Farmer-Laborites.

Born as the primary opposition to the Republicans in Minnesota, where the state Democratic Party never recovered its pre-statehood dominance, the Farmer-Labor Party had their first taste of power in the Underwood administration when the 1924 election shook out a Senate composed of 47 Democrats, 47 Republicans, and their 2 Minnesota seats; thus, they held the balance of power in the chamber, and they made sure the Democrats paid them their dues when they wanted legislation through the Senate. The 1926 elections saw this Senate dynamic go away when the Democrats took advantage of an overexposed Republican class from the 1920 landslide to actually gain several seats and the Senate majority, but the Farmer-Laborites gained something far more valuable: the balance of power in the House, where the Democrats retained a plurality but were denied an outright majority. That required an actual coalition to be negotiated in order to elect a speaker, and with calls for farm relief already on the rise since 1924, the Farmer-Laborites made their move.

This once again exposed the divisions of the Republican Party. Conservatives who didn't represent Western seats that knew the pain of the Dust Bowl were rather hostile to the idea, while Progressives, like former Agriculture Secretary Henry C. Wallace's son Henry A. Wallace, were more open to it. When the 1928 RNC convened, it was the key dividing line between the two strongest candidates, Lowden and former Commerce Secretary turned California Governor Herbert Hoover: Hoover, in theory the more "progressive" candidate, was actually against the Farm Relief Act, and advocated instead a plan based around modernization, electrification, and tariffs, as well as a farm board, while Lowden, though more conservative, was in favor of the passed Act. In a bitter convention, the Lowden forces scored a victory when the delegates approved platform plank in favor of the act. This took the wind out of the Hoover campaign and enabled Lowden to win the nomination. But it had been at a cost. The party had been deeply divided both pro-relief vs. anti-relief and progressive vs. conservative lines, and almost everyone in the party had a reason to differed with Lowden on at least one of the lines. Meanwhile, the party platform being pro-relief made it very pro-status quo; indeed, many claimed that the only real difference between Lowden and Underwood was that the former was a dry and the latter a wet, and the only reason no third-party emerged was because Fighting Bob had died in 1925 and no one had yet taken up his mantle. The choice of Gifford Pinchot for the vice-presidency was intended to balance the ticket with a progressive, but many had already decided they were sitting this one out because they just didn't like Lowden, and alienated anti-farm relief conservatives, who ended up also staying home. Charles G. Dawes, a former Harding administration official who had been the early favorite for the vice-presidential nomination, would have been more unifying, but was, like Lowden, an Illinoisian, and so the possibility of constitutional issues over Illinois' electoral votes in the case of a close election precluded his selection; an offer to Hoover was rejected when Lowden refused to countenance the opposite move.

In the end, turnout was only barely higher than 1924's, and arguably only because that election's turnout had already been absurdly low. The results showed danger in other areas, too: Underwood proved his wins in New York, New Hampshire, and Rhode Island four years prior hadn't been flukes by narrowly winning all three and flipping Massachusetts. Many noticed the prodigious influence of Al Smith in turning out Catholics, perhaps in preparation of a presidential bid of his own in four years. But there was a traditionally Democratic demographic Republicans had hoped to compete for in the aftermath of the 1920 result firmly back in their camp for two elections, and which now seemed to making the once-moribund Democratic Parties of the Northeast the vice-president's brother had decimated viable once again. Wisconsin and Minnesota seemed to have flipped as much because of them as because of the Farmer-Laborites' low-key cooperation.

The Republicans were quickly becoming a desperate animal. And there's few things more dangerous.

Last edited:

Snip

Looks like Charles W. Bryan as president as the Great Depression starts. Interesting to see how he does.

How is it federal & unitary simultaneously?

Who knowsHow is it federal & unitary simultaneously?

the same way North Korea is a Democratic People's Republic while being a monarchy.How is it federal & unitary simultaneously?

Share: