He Should Belong to the Ages: A Wikibox Series set in a Lincoln Lives TL

The

1868 United States presidential election was held on November 3, 1868. Senator Benjamin Wade of Ohio, running for the incumbent Republican Party with former Vice-President Hannibal Hamlin, defeated the National Union ticket of Vice-President Andrew Johnson of Tennessee and Senator Thomas Hendricks of Indiana and the Democratic ticket of U.S. Congressman George Pendleton of Ohio and former Senator Augustus C. Dodge of Iowa.

That the presidential term stretching from March 4, 1865 to March 4, 1869 was less complicated that the preceding term is a testament to the immense difficulties of the Civil War. Its aftermath was only a marginal improvement, however. Still, President Lincoln entered his second term with high hopes; he was excited to be a peacetime president, and hoped to quickly finish the process of Reconstruction and readmittance of the rebellious states, so that his domestic policy agenda might be passed. This approach died a quick and ignominious death, running up against the demands of Radical Republicans and basic reality, where Lincoln vastly underestimated what the challenges of Reconstruction would be.

The term began somewhat inauspiciously with new Vice-President Andrew Johnson being a drunk embarrassment at the inauguration; despite Lincoln's assertions to the contrary to the press, it quickly became clear to the president that his vice-president was an alcoholic. This would begin the souring of a once-fruitful relationship. Yet there were successes; the president's Second Inaugural Address went on to become one of his most lauded pieces of oratory, and in another speech on April 11, he made clear his support of suffrage for at least some African-Americans. This speech was heard by and infuriated one man by the name of John Wilkes Booth, an actor from Maryland who had long despised the president and sympathized with the Confederacy. Booth, who had been associated with the Confederate Secret Service, had been conspiring to kidnap or kill Lincoln for months at that point; his plans consisted of wide varieties of plots and inconsistent levels of prior planning. He heard on April 14 that Lincoln and Union General Ulysses S. Grant would be attending a play in Ford's Theater, and he immediately began plotting another assassination plot. That night he made an attempt on Lincoln and Grant's lives, along with co-conspirators sent to kill Vice-President Andrew Johnson and Secretary of State William Seward, respectively, but as he moved to take the shot at General Grant, Booth made the slightest sound; the general turned his head in response and noticed him. Moving out of the way, Booth's first shot missed; the other occupants of the presidential box were at this point made aware of Booth's presence. His plot noticed, and deciding to prioritize, Booth attempted to take a shot at the president, but was interfered by General Grant, leading Booth's second and final shot to instead graze Mary Todd Lincoln's leg. In the confusion Booth dropped his pistol, and was ultimately subdued by the president, a former wrestler, himself. He was apprehended afterwards and ultimately hung, but the president had escaped with his life. His co-conspirators were similarly caught, with the attempt on Seward's life also failing and the attempt on Johnson never even occurring, his assigned murderer instead drinking himself into a stupor at a saloon.

Crisis had been narrowly averted, both in keeping the racist drunk Johnson out of the White House and avoiding the federal government becoming a headless chicken, but the rest of Lincoln's term would see just as much as turbulence. Lincoln had always been a moderate in his party, and more radical Republicans had always longed the president would sympathize more with them. Throughout the war the president had slowly moved ideologically towards the Radicals' positions, and it had been hoped he might take their side in the post-war settlement, but Lincoln, as was his wont, initially took the moderate approach. He had been reelected on the

National Union ticket, after all, and intended to make good on the name. He earnestly believed the South would turn the page on the Civil War, and could be convinced to adopt the limited Black suffrage he favored. The president was bound for disappointment, however, when the electoral results of the South throughout 1865 came in. The vast majority of officials elected were former Confederates; the president was particularly galled by Georgia's election of former Confederate Vice-President Alexander Stephens to the Senate. The solidly Republican Congress largely refused to seat them; Lincoln agreed with this move, over the objections of Vice-President Johnson. Nonetheless, the president did place a limit on how far he was willing to take Reconstruction; if he could not have quick Reconstruction he would at least have a moderate but muscular one. Johnson's total opposition to Reconstruction was duly noted and ignored.

Lincoln's main issue throughout his term quickly turned out to be the divide between Congress - firmly dominated by Radical Republicans like Speaker Schuyler Colfax and soon-to-be Senate President Pro Tempore Benjamin Wade - and himself. Nevertheless, he was determined to remain allied to the Radical Republicans, given his long habit of promoting capable rivals to Cabinet positions; his conciliatory tone applied to both to the country as a whole and his party, and his personal tact was instrumental in keeping Radical Republican Cabinet members like James Speed and William Dennison from resigning. Meanwhile, the 39th Congress quickly became busy at passing Radical Reconstruction bills. Vice-President Johnson thought that the president, who considered many of them too radical, should veto them all, but Lincoln, a far cannier politician than Johnson, realized that alienating Congress would be counterproductive, especially because he had a number of economic proposals he wanted to pass (those internal improvements weren't going to build themselves) that would need congressional approval. Throughout 1866 Lincoln negotiated with Congress on these early civil rights bills. He signed the Civil Rights Act of 1866, which would soon be codified into the constitution, granting citizenship to African-Americans, despite considering some amendments in exchange for the passage of a bill on tariff policy, banking, and greenbacks. Several other bills were watered down compared to their original versions in order to avoid a presidential veto; though weaker than they could have been, Lincoln most definitely ensured their enforcement, while Andrew Johnson grumbled that he thought they ought not to be enforced at all. Congress also passed the Thirteenth Amendment, forbidding slavery, and the Fourteenth Amendment, ensuring birthright citizenship, strengthening due process, and establishing equal protection. The former was passed with Lincoln's support; the latter the president was neutral on but acceded to it when it was passed, though it would take until 1868 for the Fourteenth Amendment to garner the support of sufficient states to pass. Johnson acceded to the Thirteenth Amendment but bitterly opposed the Fourteenth. Lincoln also signed laws admitting Nebraska and Colorado as states, though he did vacillate on the latter due to its low population before ultimately signing it.

Soon the 1866 midterms approached. Lincoln's approach, despite his compromises with Radicals, very much dissatisfied them. Meanwhile, many northern Democrats, and even some moderate Republicans were beginning to outright oppose Reconstruction, although in the immediate aftermath of the war this opinion was somewhat oppressed. Anti-Reconstruction political forces soon decided they needed to build themselves up in order to contest the 1868 election. Vice-President Johnson, whom Radical Republicans once wishcasted as more radical than Lincoln, quickly turned himself into the focus of these groups. He had the distinction of being basically the only electable southerner left, and they turned to him as their leader. However, given his 1864 election, he was reluctant to join the Democratic Party. The Republican Party had already abandoned the National Union label; Johnson was drawn to it and used during the 1866 campaign, hoping to become the main opposition to the Republican Party. The National Union Party largely attracted former war Democrats and some moderate Republicans leery of the Radicals but unwilling to ever vote Democratic. Meanwhile, the loss of these sections made former Copperheads the only real ideological faction left in the Democratic Party (though Catholics and immigrants would also largely vote for them in November, these groups largely voted Democratic out of habit and did little to shift the party's platform on issues beyond nativism). This made it easy to brand Democrats as traitors, and the party declined as a result, ultimately coming in third. Meanwhile, Johnson took the unusual step of taking to the stump for the National Union in 1866 campaign. His tour was erratic, bizarre, and full of drunk public speeches that turned off many potential voters; it was labeled a major reason for the National Union's defeat, and would haunt Johnson during the 1868 campaign. Meanwhile, anti-Reconstruction sentiment was yet to set in like it would two years later, so the most motivated voters were, in fact, the Radical Republicans; the final coup de grace was that Lincoln, while by all actions aligned with the Republicans, was more reticent than the rest of the party to drop the National Union label so soon, and despite not really being affiliated with the new party, the president stubbornly continued to call himself a national unionist. That the president and vice-president both seemed to be of it put the stench of incumbency on the National Union, and so the midterm opposition advantage did not seriously hurt the Republicans. Thus the collapse of the National Union and Democratic campaigns, the motivation of Radical Republicans, and an unusual difficulty in telling who was actually the incumbent presidential party all combined to give the Republicans another major victory, holding onto their veto-proof majorities in both houses. Lincoln formally abandoned the National Union label and retook the Republican one in 1867.

The rest of Lincoln's term largely consisted of further compromises with congressional Radical Republicans to continue Reconstruction; though Lincoln disliked the policy, he felt that as long white southerners insisted on relitigating the Civil War it would remain necessary. William Seward did successfully negotiate to purchase Alaska from Russia, mocked by some as "Seward's Icebox" but overall a popular move that solidified the Republican position. However, the nearing election of 1868 began to dominate discussion. Radical Republicans had been making moves to take control of the 1868 convention, but Lincoln believed these did not pose a threat and that he could assure his choice in the 1868 Republican National Convention, which by its opening had long been Seward. Many raised the alarm that only Lincoln running for a third term or a candidacy by Ulysses S. Grant could defeat the Radical candidate - expected to be Senate President Pro Tempore Wade - but President Lincoln refused to even consider running for a third term and Grant indicated he would accept, but not seek, the Republican nomination. In the end the moderate forces followed the president's lead, with Seward the seeming frontrunner for the nomination. At the actual convention, however, the dominance of the Radicals became immediately apparent. Wade took an easy lead on the first ballot, falling just short of a majority, with Seward a distant second and scattered votes for favorite sons, minor candidates, and those who still wanted Grant or Lincoln. Wade clinched the nomination on the second ballot, shocking the nation and the moderates, many of whom now predicted defeat. Hopes that a moderate might be named for vice-president were dashed as a convention now clearly dominated by a radical fever nominated former Vice-President Hannibal Hamlin to return to his former office. Most moderates thought Wade's radicalism electoral poison, especially as anti-Reconstruction sentiment surged in a way it hadn't before 1866. President Lincoln did, though somewhat reluctantly, support his party's nominee. He also used those federal troops stationed in the south to avoid the suppression of eligible Black voters, credited with ensuring Wade's wins in the former Confederacy.

Wade's candidacy would be saved by the missteps of the opposition. Despite his disastrous 1866 tour Johnson still emerged as the only real candidate the National Union Party had, and so was nominated by it without any real difficulty; after considering Francis P. Blair Jr. of Missouri, the namesake son of his good friend, he decided Senator Thomas Hendricks of Indiana, a free-state anti-Reconstructionist, balanced the ticket better. Unusually for the time, he once again toured the nation during the general election; it went as poorly as his 1866 tour, which severely hurt his campaign. Meanwhile the Democrats, dominated by former Copperheads, wanted to nominate Convention Chairman and former New York Governor Horatio Seymour, but he steadfastly refused to be a candidate; in his place they nominated their 1864 vice-presidential candidate former Rep. George H. Pendleton of Ohio, a hugely controversial figure for both his pro-peace position during the Civil War and his economic populism. The latter caused many economically conservative Democratic leaders to abandon Pendleton in favor of Johnson, which ensured the vice-president would secure second place in the election, but Pendleton remained the candidate of many voters, splitting the anti-Wade vote.

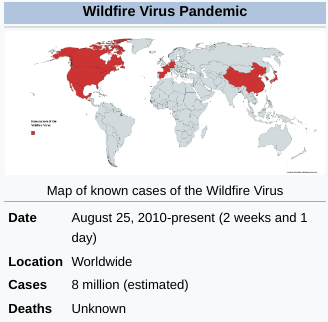

On Election Day, Senator Wade shocked many by not just winning, but winning resoundingly, winning 256 electoral votes and defeating Johnson, his closest competitor, by over 10% in the popular vote, though he won only a plurality of 45.7%. Wade carried all of the south and most of the north, the former largely off the votes of African-Americans. At the state level Republicans did as well, easily holding both houses of Congress and several state legislatures, even in Indiana, a state that Wade had lost, costing Hendricks his Senate seat. Johnson came in second in the national popular vote, and most of the north and Upper South; he won the border states of Maryland and Delaware and the Lower North states of New Jersey and Indiana, long the most south-sympathetic states in the north. Pendleton managed to win powerfully Copperhead Kentucky, one of two states (alongside Maryland) where Wade was pushed to third, and generally polled a narrow second in the Deep South (save the once Whig-leaning state of Louisiana), but otherwise came a distant third nationally in what was to be the Democratic Party's last independent campaign. While it was clear his win was only due to the divisions between the National Union and Democrats, the man who was quite possibly the most Radical Republican of them all had nonetheless just been elected president, and was coming in with a two-thirds majority in Congress. Things were about to get interesting.