I'm bored of all these Romanwanks out there, and, not seeing what I wanted, decided to do a Macedonwank.

I have made a few assumptions here, but I don't think that there are any glaring errors or major clichés.

Anyway, here we go.

**********

In the year 13, Alexander returned to his new capital in Babylon and, after entertaining his admiral Nearchus and drinking with Medius of Larissa, retired to his bed with a fever, which continued to grow worse. Ten days into the fever, Alexander lost the ability to speak, and a day later rumours began to spread that Alexander was dead. His generals gave in to the soldiers’ demands, and allowed them to see the ill emperor, reassuring them that he lived.

Rumours, however, have a habit of growing faster than the truth, and it was midsummer when the city of Athens, believing that Alexander was dead, revolted against him with the aid of several other cities, including Corinth. Alexander, however, had recovered several days previously, and when news arrived that he was marching back home with all the troops he could muster, a second, loyalist rebellion broke out in Greece. Thus, when Alexander arrived in Greece, he found it in a state of almost complete anarchy, with the loyalist rebels losing badly. Alexander came upon Athens with a force of 33,000 men and razed to the ground, and ploughed and salted the land. After this, Corinth tried to surrender, but Alexander had decided that the Greeks had rebelled too many times. Corinth received the same treatment as Athens, and the citizens of both cities were sold into slavery. It was at this time that Alexander's heir, Alexander IV, was born.

Satisfied that Greece was finally subjugated, Alexander returned to Pella for several months, planning new campaigns. Returning to Babylon, Alexander announced a campaign to the north of Asia Minor, subjugating the small states which lay there. He started by invading Bithynia with 30,000 veterans, subjugating it within months. He then left a small garrison in Heraclea, and pushed on to Sinope, where he accepted the surrender of the King of Pontus. He rested his troops here over the winter, before pushing on in the spring. He invaded Egrisi in late spring, and, by mid autumn, had taken his army to the Caucasus mountain range, which he declared as his new northern frontier, before returning to Babylon, where he spent the next year sorting out the myriad of problems beginning to assault his new Empire, sending envoys to the Indian states, promising peace and friendship.

During this time, he was also making final arrangements for the conquest of Arabia. This would be his greatest campaign since his illness, and he relished the challenge, leaving Babylon in early spring, and, with the support of the fleet he commissioned two years previously, began to advance down the Arabian coast of the Persian Gulf. He met little resistance until he reached Magan, where he was received cordially, and informed that they could pass through the realm peacefully. Alexander left behind garrisons in important cities in order to be sure of their loyalty, and replaced these men by recruiting local men into his army.

Sheba also acquiesced peacefully to Alexander, but he was held up by Ma'in, to the north. Ma'in was, however, unable to stand up to his 40,000 strong army, and as Alexander's army appeared on the horizon, many of the cities sued for peace, which pleased Alexander. This, however, was not the case with Karna and Yathill, which both resisted. Yathill was razed and its population enslaved, but Karna, being the capital, was spared, and Alexander left a garrison in the city. This left Alexander with only the Red Sea coast to traverse, and, even with the support of his fleet, the army was beginning to go hungry. By this point, luckily, he was nearing the north of the peninsula, and his fleet was able to raid the Nabataeans for supplies. This, however, left them hostile to Alexander and his army, and though they managed little or no meaningful resistance, they were discontented for many years afterwards.

This campaign was considered to have brought all of Arabia under Macedonian rule, though the centre of the peninsula remained sparsely settled and was not really brought to heel for generations.

Upon his return, Alexander ordered the construction of a canal between the Red Sea and the Nile, along the route of that built by Darius under Persian rule. This was a project which took many years, and was halted twice, first by a revolt in Persia, which Alexander put down with great cruelty, and second, by an invasion of Aksum which took several years to complete. The canal was finally completed in the year 36, taking almost 20 years.

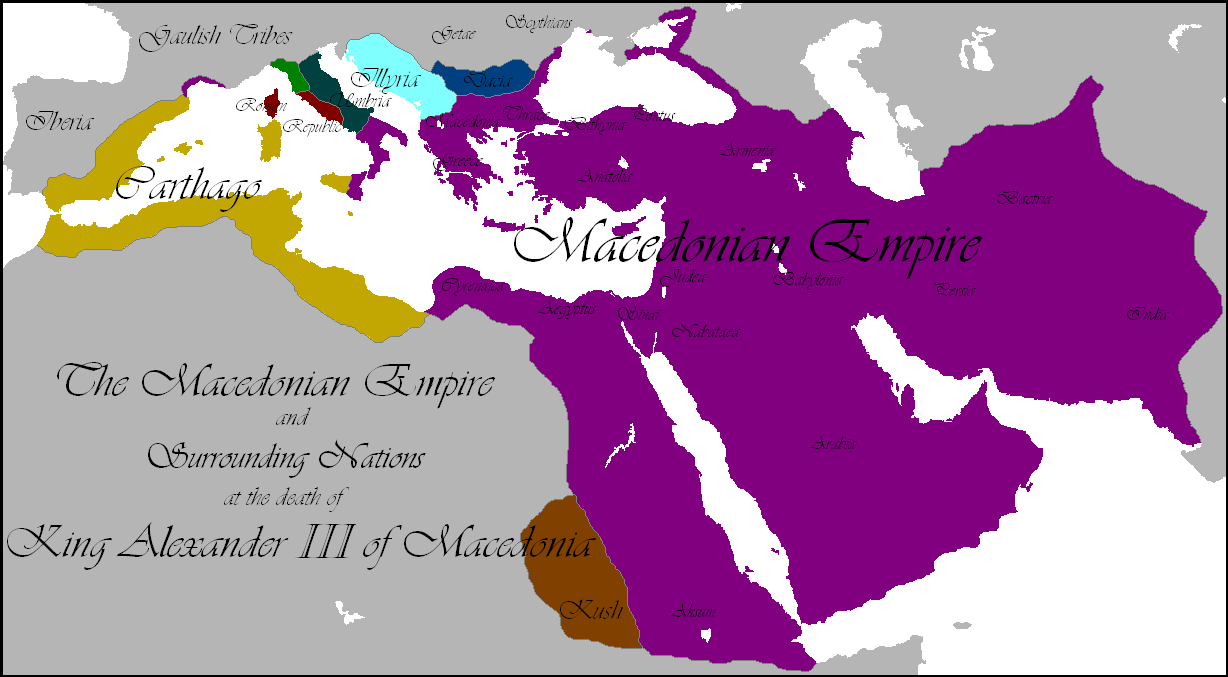

By this time, Alexander was terminally ill, and, with great reluctance, decided that his planned campaign against Carthago would have to be left to his son. In the year 37, just months before his death, Alexander officially named Alexander IV as his heir to the Macedonian Empire, and called all of his governors, satraps, generals and officials to swear loyalty to them. Several from Bactria and India refused, so Alexander IV set off with a force of 30,000 to subjugate them, his first military campaign. He was successful, but on his way home, rich with plunder, news reached him of his father's death and an invasion by Carthago, taking advantage of the lack of troops to conquer much of Egypt.

King Alexander of Macedon, fourth of that name, was now faced with the only other major power in the Mediterranean. He began forcing his men west, but Carthago, faced with little resistance, was growing dangerously close to the Nile...

I have made a few assumptions here, but I don't think that there are any glaring errors or major clichés.

Anyway, here we go.

**********

In the year 13, Alexander returned to his new capital in Babylon and, after entertaining his admiral Nearchus and drinking with Medius of Larissa, retired to his bed with a fever, which continued to grow worse. Ten days into the fever, Alexander lost the ability to speak, and a day later rumours began to spread that Alexander was dead. His generals gave in to the soldiers’ demands, and allowed them to see the ill emperor, reassuring them that he lived.

Rumours, however, have a habit of growing faster than the truth, and it was midsummer when the city of Athens, believing that Alexander was dead, revolted against him with the aid of several other cities, including Corinth. Alexander, however, had recovered several days previously, and when news arrived that he was marching back home with all the troops he could muster, a second, loyalist rebellion broke out in Greece. Thus, when Alexander arrived in Greece, he found it in a state of almost complete anarchy, with the loyalist rebels losing badly. Alexander came upon Athens with a force of 33,000 men and razed to the ground, and ploughed and salted the land. After this, Corinth tried to surrender, but Alexander had decided that the Greeks had rebelled too many times. Corinth received the same treatment as Athens, and the citizens of both cities were sold into slavery. It was at this time that Alexander's heir, Alexander IV, was born.

Satisfied that Greece was finally subjugated, Alexander returned to Pella for several months, planning new campaigns. Returning to Babylon, Alexander announced a campaign to the north of Asia Minor, subjugating the small states which lay there. He started by invading Bithynia with 30,000 veterans, subjugating it within months. He then left a small garrison in Heraclea, and pushed on to Sinope, where he accepted the surrender of the King of Pontus. He rested his troops here over the winter, before pushing on in the spring. He invaded Egrisi in late spring, and, by mid autumn, had taken his army to the Caucasus mountain range, which he declared as his new northern frontier, before returning to Babylon, where he spent the next year sorting out the myriad of problems beginning to assault his new Empire, sending envoys to the Indian states, promising peace and friendship.

During this time, he was also making final arrangements for the conquest of Arabia. This would be his greatest campaign since his illness, and he relished the challenge, leaving Babylon in early spring, and, with the support of the fleet he commissioned two years previously, began to advance down the Arabian coast of the Persian Gulf. He met little resistance until he reached Magan, where he was received cordially, and informed that they could pass through the realm peacefully. Alexander left behind garrisons in important cities in order to be sure of their loyalty, and replaced these men by recruiting local men into his army.

Sheba also acquiesced peacefully to Alexander, but he was held up by Ma'in, to the north. Ma'in was, however, unable to stand up to his 40,000 strong army, and as Alexander's army appeared on the horizon, many of the cities sued for peace, which pleased Alexander. This, however, was not the case with Karna and Yathill, which both resisted. Yathill was razed and its population enslaved, but Karna, being the capital, was spared, and Alexander left a garrison in the city. This left Alexander with only the Red Sea coast to traverse, and, even with the support of his fleet, the army was beginning to go hungry. By this point, luckily, he was nearing the north of the peninsula, and his fleet was able to raid the Nabataeans for supplies. This, however, left them hostile to Alexander and his army, and though they managed little or no meaningful resistance, they were discontented for many years afterwards.

This campaign was considered to have brought all of Arabia under Macedonian rule, though the centre of the peninsula remained sparsely settled and was not really brought to heel for generations.

Upon his return, Alexander ordered the construction of a canal between the Red Sea and the Nile, along the route of that built by Darius under Persian rule. This was a project which took many years, and was halted twice, first by a revolt in Persia, which Alexander put down with great cruelty, and second, by an invasion of Aksum which took several years to complete. The canal was finally completed in the year 36, taking almost 20 years.

By this time, Alexander was terminally ill, and, with great reluctance, decided that his planned campaign against Carthago would have to be left to his son. In the year 37, just months before his death, Alexander officially named Alexander IV as his heir to the Macedonian Empire, and called all of his governors, satraps, generals and officials to swear loyalty to them. Several from Bactria and India refused, so Alexander IV set off with a force of 30,000 to subjugate them, his first military campaign. He was successful, but on his way home, rich with plunder, news reached him of his father's death and an invasion by Carthago, taking advantage of the lack of troops to conquer much of Egypt.

King Alexander of Macedon, fourth of that name, was now faced with the only other major power in the Mediterranean. He began forcing his men west, but Carthago, faced with little resistance, was growing dangerously close to the Nile...