With a POD range as early as 1850 the challenge is to mitigate the Panic of 1873 and Long Depression in Britain in addition to the Great Depression of British Agriculture IOTL from 1873 to 1896.

Am interested to know the consequences of how a better British performance during the period from 1973 to 1896 ITTL would have helped the British not fall completely behind Germany and the United States during the Second Industrial Revolution between 1870 to 1914, since it seems the British approach to the Panic of 1873 below played a role in causing them to fall behind (and led to the Long Depression, etc).

OTL UK in Panic of 1873

OTL UK in the Second Industrial Revolution

Am interested to know the consequences of how a better British performance during the period from 1973 to 1896 ITTL would have helped the British not fall completely behind Germany and the United States during the Second Industrial Revolution between 1870 to 1914, since it seems the British approach to the Panic of 1873 below played a role in causing them to fall behind (and led to the Long Depression, etc).

OTL UK in Panic of 1873

Britain

The opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 was one of the causes of the Panic of 1873 because goods from the Far East had been carried in sailing vessels around the Cape of Good Hope and were stored in British warehouses. As sailing vessels were not adaptable for use through the Suez Canal because the prevailing winds of the Mediterranean Sea blow from west to east, the British entrepôt trade suffered.

When the crisis came, the Bank of England raised interest rates to 9 percent. Despite this, Britain did not experience the scale of financial mayhem seen in America and Central Europe, perhaps forestalled by an expectation that the liquidity-constraining provisions of the Bank Charter Act of 1844 would be suspended as they had been in the crises of 1847, 1857 and 1866. The ensuing economic downturn in Britain seems to have been muted – "stagnant" but without a "decline in aggregate output". However there was heavy unemployment in the basic industries of coal, iron and steel, engineering, and shipbuilding, especially in 1873, 1886 and 1893.

Comparison with Germany

From 1873 to 1896, a period sometimes referred to as the Long Depression, most European countries experienced a drastic fall in prices. Still, many corporations were able to reduce production costs and achieve better productivity rates, with industrial production increasing by 40% in Britain and by over 100% in Germany. A comparison of capital formation rates in both countries helps to account for the different industrial growth rates. During the depression, the British ratio of net national capital formation to net national product fell from 11.5% to 6.0%, but the German ratio rose from 10.6% to 15.9%. During the depression, Britain took the course of static supply adjustment, but Germany stimulated effective demand and expanded industrial supply capacity by increasing and adjusting capital formation. For example, Germany dramatically increased investment of social overhead capital, such as in the management of electric power transmission lines, roads, and railroads, thereby stimulating industrial demand in that country, but similar investment stagnated or decreased in Britain. The resulting difference in capital formation accounts for the divergent levels of industrial production in the two countries and the different growth rates during and after the depression.

OTL UK in the Second Industrial Revolution

United Kingdom

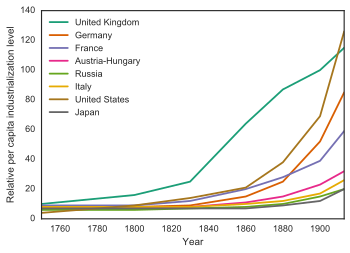

Relative per capita levels of industrialization, 1750–1910.

New products and services were introduced which greatly increased international trade. Improvements in steam engine design and the wide availability of cheap steel meant that slow, sailing ships were replaced with faster steamship, which could handle more trade with smaller crews. The chemical industries also moved to the forefront. Britain invested less in technological research than the U.S. and Germany, which caught up.

The development of more intricate and efficient machines along with mass production techniques (after 1910) greatly expanded output and lowered production costs. As a result, production often exceeded domestic demand. Among the new conditions, more markedly evident in Britain, the forerunner of Europe's industrial states, were the long-term effects of the severe Long Depression of 1873–1896, which had followed fifteen years of great economic instability. Businesses in practically every industry suffered from lengthy periods of low — and falling — profit rates and price deflation after 1873.