Chapter Zero: Election Time Part I (1985 - 12 June 1991)

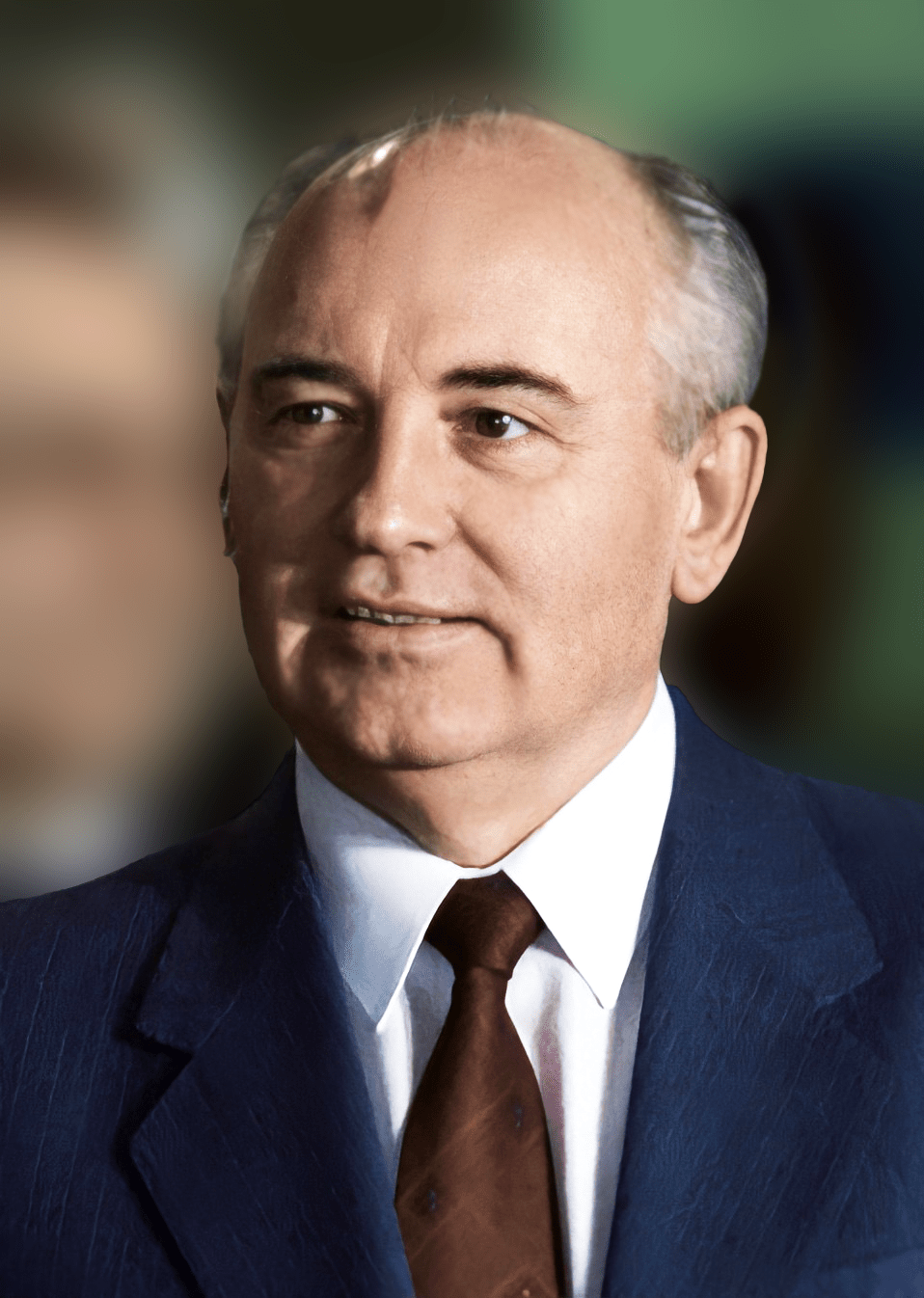

After years of stagnation, the "new thinking" of younger Communist apparatchik began to emerge. Following the death of terminally ill Konstantin Chernenko, the Politburo elected Mikhail Gorbachev to the position of General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) in March 1985. At 54, Gorbachev was the youngest person since Joseph Stalin to become General Secretary and the country's first head of state born a Soviet citizen instead of a subject of the tsar. During his official confirmation on 11 March, Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko spoke of how the new Soviet leader had filled in for Chernenko as CC Secretariat, and praised his intelligence and flexible, pragmatic ideas instead of rigid adherence to party ideology. Gorbachev was aided by a lack of serious competition in the Politburo. He immediately began appointing younger men of his generation to important party posts, including Nikolai Ryzhkov, Secretary of Economics, Viktor Cherbrikov, KGB Chief, Foreign Minister Eduard Shevardnadze (replacing the 75-year-old Gromyko), Secretary of Defense Industries Lev Zaikov, and Secretary of Construction Boris Yeltsin. Removed from the Politburo and Secretariat was Grigory Romanov, who had been Gorbachev's most significant rival for the position of General Secretary. Gromyko's removal as Foreign Minister was the most unexpected change given his decades of unflinching, faithful service compared to the unknown, inexperienced Shevardnadze. More predictably, the 80-year-old Nikolai Tikhonov, the Chairman of the Council of Ministers, was succeeded by Nikolai Ryzhkov, and Vasili Kuznetsov, the acting Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet, was succeeded by Andrei Gromyko, the former Minister of Foreign Affairs.

(Instead of saving the USSR, Gorbachev killed the first proletariat state in the world)

Further down the chain, up to 40% of the first secretaries of the oblasts (provinces) were replaced with younger, better educated, and more competent men. The defense establishment was also given a thorough shakeup with the commanders of all 16 military districts replaced along with all theaters of military operation, as well as the three Soviet fleets. Not since World War II had the Soviet military had such a rapid turnover of officers. Sixty-eight-year-old Marshal Nikolai Ogarkov was fully rehabilitated after having fallen from favor in 1983–84 due to his handling of the KAL 007 shootdown and his ideas about improving Soviet strategic and tactical doctrines were made into an official part of defense policy, although some of his other ambitions such as developing the military into a smaller, tighter force based on advanced technology were not considered feasible for the time being. Many, but not all, of the younger army officers appointed during 1985 were proteges of Ogarkov. Gorbachev got off to an excellent start during his first months in power. He projected an aura of youth and dynamism compared to his aged predecessors and made frequent walks in the streets of the major cities answering questions from ordinary citizens. He became the first leader that spoke with the Soviet people in person. When he made public speeches, he made clear that he was interested in constructive exchanges of ideas instead of merely reciting lengthy platitudes about the excellence of the Soviet system. He also spoke candidly about the slackness and run-down condition of Soviet society in recent years, blaming alcohol abuse, poor workplace discipline, and other factors for these situations. Alcohol was a particular nag of Gorbachev's, especially as he himself did not drink, and he made one of his major policy aims curbing the consumption of it.

East-West tensions increased during the first term of US President Ronald Reagan (1981–85), reaching levels not seen since the Cuban Missile Crisis as Reagan increased US military spending to 7% of the GDP. To match the military buildup, the Soviet Union increased its own military spending to 27% of its GDP and froze production of civilian goods at 1980 levels, causing a sharp economic decline in the already failing Soviet economy. The US financed the training for the Mujahideen warlords such as Jalaluddin Haqqani, Gulbudin Hekmatyar and Burhanuddin Rabbani eventually culminated to the fall of the Soviet satellite the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan. While the CIA and MI6 and the People's Liberation Army of China financed the operation along with the Pakistan government against the Soviet Union, eventually the Soviet Union began looking for a withdrawal route and in 1988 the Geneva Accords were signed between Communist-Afghanistan and the Islamic Republic of Pakistan; under the terms Soviet troops were to withdraw. Once the withdrawal was complete the Pakistan ISI continued to support the Mujahideen against the Communist Government and by 1992, the government collapsed. US President Reagan also actively hindered the Soviet Union's ability to sell natural gas to Europe whilst simultaneously actively working to keep gas prices low, which kept the price of Soviet oil low and further starved the Soviet Union of foreign capital. This "long-term strategic offensive," which "contrasts with the essentially reactive and defensive strategy of "containment", accelerated the fall of the Soviet Union by encouraging it to overextend its economic base. The proposition that special operations by the CIA in Saudi Arabia affected the prices of Soviet oil was refuted by Marshall Goldman—one of the leading experts on the economy of the Soviet Union—in his latest book. He pointed out that the Saudis decreased their production of oil in 1985 (it reached a 16-year low), whereas the peak of oil production was reached in 1980. They increased the production of oil in 1986, reduced it in 1987 with a subsequent increase in 1988, but not to the levels of 1980 when production reached its highest level. The real increase happened in 1990, by which time the Cold War was almost over. In his book he asked why, if Saudi Arabia had such an effect on Soviet oil prices, did prices not fall in 1980 when the production of oil by Saudi Arabia reached its highest level—three times as much oil as in the mid-eighties—and why did the Saudis wait till 1990 to increase their production, five years after the CIA's supposed intervention? Why didn't the Soviet Union collapse in 1980 then?" By the time Gorbachev ushered in the process that would lead to the dismantling of the Soviet administrative command economy through his programs of uskoreniye (speed-up of economic development) and perestroika (political and economic restructuring) announced in 1986, the Soviet economy suffered from both hidden inflation and pervasive supply shortages aggravated by an increasingly open black market that undermined the official economy. Additionally, the costs of superpower status—the military, space program, subsidies to client states—were out of proportion to the Soviet economy. The new wave of industrialization based upon information technology had left the Soviet Union desperate for Western technology and credits in order to counter its increasing backwardness.

(Goods shortage in the USSR)

The Law on Cooperatives enacted in May 1988 was perhaps the most radical of the economic reforms during the early part of the Gorbachev era. For the first time since Vladimir Lenin's New Economic Policy, the law permitted private ownership of businesses in the services, manufacturing, and foreign-trade sectors. Under this provision, cooperative restaurants, shops, and manufacturers became part of the Soviet scene. Glasnost resulted in greater freedom of speech and the press becoming far less controlled. Thousands of political prisoners and many dissidents were also released.Soviet social science became free to explore and publish on many subjects that had previously been off limits, including conducting public opinion polls. The All−Union Center for Public Opinion Research (VCIOM)—the most prominent of several polling organizations that were started then— was opened. State archives became more accessible, and some social statistics that had been kept secret became open for research and publication on sensitive subjects such as income disparities, crime, suicide, abortion, and infant mortality. The first center for gender studies was opened within a newly formed Institute for the Socio−Economic Study of Human Population. In January 1987, Gorbachev called for democratization: the infusion of democratic elements such as multi-candidate elections into the Soviet political process. A 1987 conference convened by Soviet economist and Gorbachev adviser Leonid Abalkin, concluded: "Deep transformations in the management of the economy cannot be realized without corresponding changes in the political system." In June 1988, at the CPSU's Nineteenth Party Conference, Gorbachev launched radical reforms meant to reduce party control of the government apparatus. On 1 December 1988, the Supreme Soviet amended the Soviet constitution to allow for the establishment of a Congress of People's Deputies as the Soviet Union's new supreme legislative body.

Elections to the new Congress of People's Deputies were held throughout the USSR in March and April 1989. Gorbachev, as General Secretary of the Communist Party, could be forced to resign at any moment if the communist elite became dissatisfied with him. To proceed with reforms opposed by the majority of the communist party, Gorbachev aimed to consolidate power in a new position, President of the Soviet Union, which was independent from the CPSU and the soviets (councils) and whose holder could be impeached only in case of direct violation of the law. On 15 March 1990, Gorbachev was elected as the first executive president. At the same time, Article 6 of the constitution was changed to deprive the CPSU of a monopoly on political power. Gorbachev's efforts to streamline the Communist system offered promise, but ultimately proved uncontrollable and resulted in a cascade of events that eventually concluded with the dissolution of the Soviet Union. Initially intended as tools to bolster the Soviet economy, the policies of perestroika and glasnost soon led to unintended consequences.

Relaxation under glasnost resulted in the Communist Party losing its absolute grip on the media. Before long, and much to the embarrassment of the authorities, the media began to expose severe social and economic problems the Soviet government had long denied and actively concealed. Problems receiving increased attention included poor housing, alcoholism, drug abuse, pollution, outdated Stalin-era factories, and petty to large-scale corruption, all of which the official media had ignored. Media reports also exposed crimes committed by Joseph Stalin and the Soviet regime, such as the gulags, his treaty with Adolf Hitler, and the Great Purges, which had been ignored by the official media. Moreover, the ongoing war in Afghanistan, and the mishandling of the 1986 Chernobyl disaster, further damaged the credibility of the Soviet government at a time when dissatisfaction was increasing. In all, the positive view of Soviet life long presented to the public by the official media was rapidly fading, and the negative aspects of life in the Soviet Union were brought into the spotlight. This undermined the faith of the public in the Soviet system and eroded the Communist Party's social power base, threatening the identity and integrity of the Soviet Union itself. Fraying amongst the members of the Warsaw Pact countries and instability of its western allies, first indicated by Lech Wałęsa's 1980 rise to leadership of the trade union Solidarity, accelerated, leaving the Soviet Union unable to depend upon its Eastern European satellite states for protection as a buffer zone. By 1989, following his doctrine of "new political thinking", Gorbachev had repudiated the Brezhnev Doctrine in favor of non-intervention in the internal affairs of its Warsaw Pact allies ("Sinatra Doctrine"). Gradually, each of the Warsaw Pact countries saw their communist governments fall to popular elections and, in the case of Romania, a violent uprising. By 1990, the governments of Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, East Germany, Hungary, Poland and Romania, all of which had been imposed after World War II, were brought down as revolutions swept Eastern Europe.

(Fall of the Berlin Wall)

The Soviet Union also began experiencing upheaval as the political consequences of glasnost reverberated throughout the country. Despite efforts at containment, the upheaval in Eastern Europe inevitably spread to nationalities within the USSR. In elections to the regional assemblies of the Soviet Union's constituent republics, nationalists as well as radical reformers swept the board. As Gorbachev had weakened the system of internal political repression, the ability of the USSR's central Moscow government to impose its will on the USSR's constituent republics had been largely undermined. Massive peaceful protests in the Baltic republics such as the Baltic Way and the Singing Revolution drew international attention and bolstered independence movements in various other regions. The rise of nationalism under freedom of speech soon re-awakened simmering ethnic tensions in various Soviet republics, further discrediting the ideal of a unified Soviet people. One instance occurred in February 1988, when the government in Nagorno-Karabakh, a predominantly ethnic Armenian region in the Azerbaijan SSR, passed a resolution calling for unification with the Armenian SSR. Violence against local Azerbaijanis was reported on Soviet television, provoking massacres of Armenians in the Azerbaijani city of Sumgait. Emboldened by the liberalized atmosphere of glasnost, public dissatisfaction with economic conditions was much more overt than ever before in the Soviet period. Although perestroika was considered bold in the context of Soviet history, Gorbachev's attempts at economic reform were not radical enough to restart the country's chronically sluggish economy in the late 1980s. The reforms made some inroads in decentralization, but Gorbachev and his team left intact most of the fundamental elements of the Stalinist system, including price controls, inconvertibility of the ruble, exclusion of private property ownership, and the government monopoly over most means of production.

The value of all consumer goods manufactured in 1990 in retail prices was about 459 billion rubles ($2.1 trillion). Nevertheless, the Soviet government had lost control over economic conditions. Government spending increased sharply as an increasing number of unprofitable enterprises required state support and consumer price subsidies to continue. Tax revenues declined as republic and local governments withheld tax revenues from the central government under the growing spirit of regional autonomy. The anti−alcohol campaign reduced tax revenues as well, which in 1982 accounted for about 12% of all state revenue. The elimination of central control over production decisions, especially in the consumer goods sector, led to the breakdown in traditional supplier−producer relationships without contributing to the formation of new ones. Thus, instead of streamlining the system, Gorbachev's decentralization caused new production bottlenecks. In the election of the Supreme Soviet of Russia's Congress of People's Deputies of Russia lower chamber members in the 1990 Russian legislative election, communist candidates won 86% of the seats. On 31 May 1990, Boris Yeltsin was elected Chair of the Supreme Soviet of the Russian Federation in a vote by the body's members; this made him the de facto leader of the Russian SFSR. The vote had been relatively close, as Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev had unsuccessfully tried to convince enough members of the Supreme Soviet to vote against Yeltsin. Yelstin made an active effort to push for the creation of an office of president and for a popular election to be held to fill it. Many saw this as a desire by Yeltsin to have a mandate and power separate from the tensely divided legislature. He ultimately succeeded in having Russia hold a referendum on 14 March 1991 on whether Russia should create offices of President and Vice President, and hold elections to fill them. Russians voted in favor of creating and holding elections to these offices. Following the referendum, there was a period of more than a week in which a stalemate had caused the Congress of People's Deputies to go without deciding whether or not to vote on whether the Russian Federation should have a directly elected president. On 4 April the Congress of People's Deputies ordered the creation of legislation to authorize the election. While still failing to set an official date for the election, the Congress of People's Deputies provisionally scheduled the election for 12 June. This provisional date would later become the official date of the election. Ultimately, the Congress of People's Deputies would approve for an election to be held, scheduling its initial round of voting to be held roughly three months after the referendum had been decided. The election would jointly elect individuals to serve five-year terms as president and vice-president of the RSFSR.

(Boris Yeltsin - according to many a future president of Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic)

Several sub-national elections were scheduled to coincide with the first round of the presidential election. This included mayoral elections in Moscow and Leningrad, and executive elections in federal subjects such as Tatarstan. There were also sub-national referendums scheduled to coincide with the presidential election. These included a number of referendums in which cities were determining whether or not residents wanted to revert to their historic city names, such as in Sverdlovsk (historically Yekaterinburg) and Leningrad (historically Saint Petersburg). In a difference to subsequent Russian presidential elections, a vice-presidential candidate stood for election along with the presidential candidate. Similarly to the United States presidential election system, the candidature of Vice President of the RSFSR was exhibited along with the candidacy of the President of the RSFSR as a joint entry on the ballot paper. Preliminary legislation outlining the rules of the election was passed on 24 April by the Supreme Soviet of Russia; however, it ultimately took the Supreme Soviet until three weeks before the day of the election to finalize the rules that would govern the election. Any citizen of the RSFSR between the ages of 35 and 65 were eligible to be elected president. Any citizen of the RSFSR over the age of 18 was eligible to vote. 50% turnout was required in order to validate the election. The winner would need to have captured 50% of the votes cast. The president would be elected to a five-year term, and could serve a maximum of two terms. Originally, the election law stipulated that, once sworn in, the president would be required to renounce their membership of any political parties. On 23 May, the parliament voted to remove this requirement. All candidates needed to be nominated before they could achieve ballot registration. Candidates could be nominated by RSFSR political parties, trade unions, and public organizations. There were two ways for candidates to achieve ballot registration. The first was by providing proof of the having the support of 100,000 voters (a signature drive). The second way for candidates to obtain registration is if they received the support of 25% of the members of the Congress of People's Deputies, which would vote on whether or not to add such candidates to the ballot. On 6 May, it was announced that the deadline for nominations would be 18 May. This was also the deadline for nominating a vice-presidential running mate. Candidates were provided 200,000 rubles in public financing for their campaigns. In May 1991, there were some calls to postpone the election, rescheduling it for September. Those urging the postponement of the elections argued that the time before the scheduled 12 June election day provided too brief of a period for nominating candidates and campaigning. In response to these calls, election commission chairman Vasilii Kazakov argued that the law stipulated that the election would be held on 12 June and that the proposed postponement of the election would only serve to "keep Russia seething" for another three months. In mid-May, election commission chairman Vasilii Kazakov announced that the election would be budgeted at 155 million rubles.

The results of the first round were to be counted and announced by a 22 June deadline. It had ultimately been determined that, if needed, a runoff would be scheduled to be held within two weeks after the first round. Due to the rushed circumstances behind the creation of the office and organization the election, many aspects of the office of President were not clear. Sufficient legislative debates were not held to outline the scope of presidential powers. It was unclear, for example, whether the president or the Congress of People's Deputies would hold ultimate legislative authority. One of the few stipulations that was made was that a two-thirds vote in the Congress of People's Deputies had the power, only if such a vote were recommended by the newly created constitutional court, to remove the president if they violated the constitution, laws, or oath of office. Work on drafting a law to outline the presidency itself began on 24 April, with approximately two months until the inaugural holder was set to occupy the office. Under the initial draft the president was the chief executive in the RSFSR, but did not have the right to dismiss the Supreme Soviet or the Congress of People's Deputies or suspend their activities. The president could not be a people's deputy and, once elected, would have needed to suspend their membership in all political parties.

Now on 12 June 1991 first Russian presidential election in the country's history will take place, where the voters will decide the fate and future of Russia.

(Instead of saving the USSR, Gorbachev killed the first proletariat state in the world)

Further down the chain, up to 40% of the first secretaries of the oblasts (provinces) were replaced with younger, better educated, and more competent men. The defense establishment was also given a thorough shakeup with the commanders of all 16 military districts replaced along with all theaters of military operation, as well as the three Soviet fleets. Not since World War II had the Soviet military had such a rapid turnover of officers. Sixty-eight-year-old Marshal Nikolai Ogarkov was fully rehabilitated after having fallen from favor in 1983–84 due to his handling of the KAL 007 shootdown and his ideas about improving Soviet strategic and tactical doctrines were made into an official part of defense policy, although some of his other ambitions such as developing the military into a smaller, tighter force based on advanced technology were not considered feasible for the time being. Many, but not all, of the younger army officers appointed during 1985 were proteges of Ogarkov. Gorbachev got off to an excellent start during his first months in power. He projected an aura of youth and dynamism compared to his aged predecessors and made frequent walks in the streets of the major cities answering questions from ordinary citizens. He became the first leader that spoke with the Soviet people in person. When he made public speeches, he made clear that he was interested in constructive exchanges of ideas instead of merely reciting lengthy platitudes about the excellence of the Soviet system. He also spoke candidly about the slackness and run-down condition of Soviet society in recent years, blaming alcohol abuse, poor workplace discipline, and other factors for these situations. Alcohol was a particular nag of Gorbachev's, especially as he himself did not drink, and he made one of his major policy aims curbing the consumption of it.

East-West tensions increased during the first term of US President Ronald Reagan (1981–85), reaching levels not seen since the Cuban Missile Crisis as Reagan increased US military spending to 7% of the GDP. To match the military buildup, the Soviet Union increased its own military spending to 27% of its GDP and froze production of civilian goods at 1980 levels, causing a sharp economic decline in the already failing Soviet economy. The US financed the training for the Mujahideen warlords such as Jalaluddin Haqqani, Gulbudin Hekmatyar and Burhanuddin Rabbani eventually culminated to the fall of the Soviet satellite the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan. While the CIA and MI6 and the People's Liberation Army of China financed the operation along with the Pakistan government against the Soviet Union, eventually the Soviet Union began looking for a withdrawal route and in 1988 the Geneva Accords were signed between Communist-Afghanistan and the Islamic Republic of Pakistan; under the terms Soviet troops were to withdraw. Once the withdrawal was complete the Pakistan ISI continued to support the Mujahideen against the Communist Government and by 1992, the government collapsed. US President Reagan also actively hindered the Soviet Union's ability to sell natural gas to Europe whilst simultaneously actively working to keep gas prices low, which kept the price of Soviet oil low and further starved the Soviet Union of foreign capital. This "long-term strategic offensive," which "contrasts with the essentially reactive and defensive strategy of "containment", accelerated the fall of the Soviet Union by encouraging it to overextend its economic base. The proposition that special operations by the CIA in Saudi Arabia affected the prices of Soviet oil was refuted by Marshall Goldman—one of the leading experts on the economy of the Soviet Union—in his latest book. He pointed out that the Saudis decreased their production of oil in 1985 (it reached a 16-year low), whereas the peak of oil production was reached in 1980. They increased the production of oil in 1986, reduced it in 1987 with a subsequent increase in 1988, but not to the levels of 1980 when production reached its highest level. The real increase happened in 1990, by which time the Cold War was almost over. In his book he asked why, if Saudi Arabia had such an effect on Soviet oil prices, did prices not fall in 1980 when the production of oil by Saudi Arabia reached its highest level—three times as much oil as in the mid-eighties—and why did the Saudis wait till 1990 to increase their production, five years after the CIA's supposed intervention? Why didn't the Soviet Union collapse in 1980 then?" By the time Gorbachev ushered in the process that would lead to the dismantling of the Soviet administrative command economy through his programs of uskoreniye (speed-up of economic development) and perestroika (political and economic restructuring) announced in 1986, the Soviet economy suffered from both hidden inflation and pervasive supply shortages aggravated by an increasingly open black market that undermined the official economy. Additionally, the costs of superpower status—the military, space program, subsidies to client states—were out of proportion to the Soviet economy. The new wave of industrialization based upon information technology had left the Soviet Union desperate for Western technology and credits in order to counter its increasing backwardness.

(Goods shortage in the USSR)

The Law on Cooperatives enacted in May 1988 was perhaps the most radical of the economic reforms during the early part of the Gorbachev era. For the first time since Vladimir Lenin's New Economic Policy, the law permitted private ownership of businesses in the services, manufacturing, and foreign-trade sectors. Under this provision, cooperative restaurants, shops, and manufacturers became part of the Soviet scene. Glasnost resulted in greater freedom of speech and the press becoming far less controlled. Thousands of political prisoners and many dissidents were also released.Soviet social science became free to explore and publish on many subjects that had previously been off limits, including conducting public opinion polls. The All−Union Center for Public Opinion Research (VCIOM)—the most prominent of several polling organizations that were started then— was opened. State archives became more accessible, and some social statistics that had been kept secret became open for research and publication on sensitive subjects such as income disparities, crime, suicide, abortion, and infant mortality. The first center for gender studies was opened within a newly formed Institute for the Socio−Economic Study of Human Population. In January 1987, Gorbachev called for democratization: the infusion of democratic elements such as multi-candidate elections into the Soviet political process. A 1987 conference convened by Soviet economist and Gorbachev adviser Leonid Abalkin, concluded: "Deep transformations in the management of the economy cannot be realized without corresponding changes in the political system." In June 1988, at the CPSU's Nineteenth Party Conference, Gorbachev launched radical reforms meant to reduce party control of the government apparatus. On 1 December 1988, the Supreme Soviet amended the Soviet constitution to allow for the establishment of a Congress of People's Deputies as the Soviet Union's new supreme legislative body.

Elections to the new Congress of People's Deputies were held throughout the USSR in March and April 1989. Gorbachev, as General Secretary of the Communist Party, could be forced to resign at any moment if the communist elite became dissatisfied with him. To proceed with reforms opposed by the majority of the communist party, Gorbachev aimed to consolidate power in a new position, President of the Soviet Union, which was independent from the CPSU and the soviets (councils) and whose holder could be impeached only in case of direct violation of the law. On 15 March 1990, Gorbachev was elected as the first executive president. At the same time, Article 6 of the constitution was changed to deprive the CPSU of a monopoly on political power. Gorbachev's efforts to streamline the Communist system offered promise, but ultimately proved uncontrollable and resulted in a cascade of events that eventually concluded with the dissolution of the Soviet Union. Initially intended as tools to bolster the Soviet economy, the policies of perestroika and glasnost soon led to unintended consequences.

Relaxation under glasnost resulted in the Communist Party losing its absolute grip on the media. Before long, and much to the embarrassment of the authorities, the media began to expose severe social and economic problems the Soviet government had long denied and actively concealed. Problems receiving increased attention included poor housing, alcoholism, drug abuse, pollution, outdated Stalin-era factories, and petty to large-scale corruption, all of which the official media had ignored. Media reports also exposed crimes committed by Joseph Stalin and the Soviet regime, such as the gulags, his treaty with Adolf Hitler, and the Great Purges, which had been ignored by the official media. Moreover, the ongoing war in Afghanistan, and the mishandling of the 1986 Chernobyl disaster, further damaged the credibility of the Soviet government at a time when dissatisfaction was increasing. In all, the positive view of Soviet life long presented to the public by the official media was rapidly fading, and the negative aspects of life in the Soviet Union were brought into the spotlight. This undermined the faith of the public in the Soviet system and eroded the Communist Party's social power base, threatening the identity and integrity of the Soviet Union itself. Fraying amongst the members of the Warsaw Pact countries and instability of its western allies, first indicated by Lech Wałęsa's 1980 rise to leadership of the trade union Solidarity, accelerated, leaving the Soviet Union unable to depend upon its Eastern European satellite states for protection as a buffer zone. By 1989, following his doctrine of "new political thinking", Gorbachev had repudiated the Brezhnev Doctrine in favor of non-intervention in the internal affairs of its Warsaw Pact allies ("Sinatra Doctrine"). Gradually, each of the Warsaw Pact countries saw their communist governments fall to popular elections and, in the case of Romania, a violent uprising. By 1990, the governments of Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, East Germany, Hungary, Poland and Romania, all of which had been imposed after World War II, were brought down as revolutions swept Eastern Europe.

(Fall of the Berlin Wall)

The Soviet Union also began experiencing upheaval as the political consequences of glasnost reverberated throughout the country. Despite efforts at containment, the upheaval in Eastern Europe inevitably spread to nationalities within the USSR. In elections to the regional assemblies of the Soviet Union's constituent republics, nationalists as well as radical reformers swept the board. As Gorbachev had weakened the system of internal political repression, the ability of the USSR's central Moscow government to impose its will on the USSR's constituent republics had been largely undermined. Massive peaceful protests in the Baltic republics such as the Baltic Way and the Singing Revolution drew international attention and bolstered independence movements in various other regions. The rise of nationalism under freedom of speech soon re-awakened simmering ethnic tensions in various Soviet republics, further discrediting the ideal of a unified Soviet people. One instance occurred in February 1988, when the government in Nagorno-Karabakh, a predominantly ethnic Armenian region in the Azerbaijan SSR, passed a resolution calling for unification with the Armenian SSR. Violence against local Azerbaijanis was reported on Soviet television, provoking massacres of Armenians in the Azerbaijani city of Sumgait. Emboldened by the liberalized atmosphere of glasnost, public dissatisfaction with economic conditions was much more overt than ever before in the Soviet period. Although perestroika was considered bold in the context of Soviet history, Gorbachev's attempts at economic reform were not radical enough to restart the country's chronically sluggish economy in the late 1980s. The reforms made some inroads in decentralization, but Gorbachev and his team left intact most of the fundamental elements of the Stalinist system, including price controls, inconvertibility of the ruble, exclusion of private property ownership, and the government monopoly over most means of production.

The value of all consumer goods manufactured in 1990 in retail prices was about 459 billion rubles ($2.1 trillion). Nevertheless, the Soviet government had lost control over economic conditions. Government spending increased sharply as an increasing number of unprofitable enterprises required state support and consumer price subsidies to continue. Tax revenues declined as republic and local governments withheld tax revenues from the central government under the growing spirit of regional autonomy. The anti−alcohol campaign reduced tax revenues as well, which in 1982 accounted for about 12% of all state revenue. The elimination of central control over production decisions, especially in the consumer goods sector, led to the breakdown in traditional supplier−producer relationships without contributing to the formation of new ones. Thus, instead of streamlining the system, Gorbachev's decentralization caused new production bottlenecks. In the election of the Supreme Soviet of Russia's Congress of People's Deputies of Russia lower chamber members in the 1990 Russian legislative election, communist candidates won 86% of the seats. On 31 May 1990, Boris Yeltsin was elected Chair of the Supreme Soviet of the Russian Federation in a vote by the body's members; this made him the de facto leader of the Russian SFSR. The vote had been relatively close, as Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev had unsuccessfully tried to convince enough members of the Supreme Soviet to vote against Yeltsin. Yelstin made an active effort to push for the creation of an office of president and for a popular election to be held to fill it. Many saw this as a desire by Yeltsin to have a mandate and power separate from the tensely divided legislature. He ultimately succeeded in having Russia hold a referendum on 14 March 1991 on whether Russia should create offices of President and Vice President, and hold elections to fill them. Russians voted in favor of creating and holding elections to these offices. Following the referendum, there was a period of more than a week in which a stalemate had caused the Congress of People's Deputies to go without deciding whether or not to vote on whether the Russian Federation should have a directly elected president. On 4 April the Congress of People's Deputies ordered the creation of legislation to authorize the election. While still failing to set an official date for the election, the Congress of People's Deputies provisionally scheduled the election for 12 June. This provisional date would later become the official date of the election. Ultimately, the Congress of People's Deputies would approve for an election to be held, scheduling its initial round of voting to be held roughly three months after the referendum had been decided. The election would jointly elect individuals to serve five-year terms as president and vice-president of the RSFSR.

(Boris Yeltsin - according to many a future president of Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic)

Several sub-national elections were scheduled to coincide with the first round of the presidential election. This included mayoral elections in Moscow and Leningrad, and executive elections in federal subjects such as Tatarstan. There were also sub-national referendums scheduled to coincide with the presidential election. These included a number of referendums in which cities were determining whether or not residents wanted to revert to their historic city names, such as in Sverdlovsk (historically Yekaterinburg) and Leningrad (historically Saint Petersburg). In a difference to subsequent Russian presidential elections, a vice-presidential candidate stood for election along with the presidential candidate. Similarly to the United States presidential election system, the candidature of Vice President of the RSFSR was exhibited along with the candidacy of the President of the RSFSR as a joint entry on the ballot paper. Preliminary legislation outlining the rules of the election was passed on 24 April by the Supreme Soviet of Russia; however, it ultimately took the Supreme Soviet until three weeks before the day of the election to finalize the rules that would govern the election. Any citizen of the RSFSR between the ages of 35 and 65 were eligible to be elected president. Any citizen of the RSFSR over the age of 18 was eligible to vote. 50% turnout was required in order to validate the election. The winner would need to have captured 50% of the votes cast. The president would be elected to a five-year term, and could serve a maximum of two terms. Originally, the election law stipulated that, once sworn in, the president would be required to renounce their membership of any political parties. On 23 May, the parliament voted to remove this requirement. All candidates needed to be nominated before they could achieve ballot registration. Candidates could be nominated by RSFSR political parties, trade unions, and public organizations. There were two ways for candidates to achieve ballot registration. The first was by providing proof of the having the support of 100,000 voters (a signature drive). The second way for candidates to obtain registration is if they received the support of 25% of the members of the Congress of People's Deputies, which would vote on whether or not to add such candidates to the ballot. On 6 May, it was announced that the deadline for nominations would be 18 May. This was also the deadline for nominating a vice-presidential running mate. Candidates were provided 200,000 rubles in public financing for their campaigns. In May 1991, there were some calls to postpone the election, rescheduling it for September. Those urging the postponement of the elections argued that the time before the scheduled 12 June election day provided too brief of a period for nominating candidates and campaigning. In response to these calls, election commission chairman Vasilii Kazakov argued that the law stipulated that the election would be held on 12 June and that the proposed postponement of the election would only serve to "keep Russia seething" for another three months. In mid-May, election commission chairman Vasilii Kazakov announced that the election would be budgeted at 155 million rubles.

The results of the first round were to be counted and announced by a 22 June deadline. It had ultimately been determined that, if needed, a runoff would be scheduled to be held within two weeks after the first round. Due to the rushed circumstances behind the creation of the office and organization the election, many aspects of the office of President were not clear. Sufficient legislative debates were not held to outline the scope of presidential powers. It was unclear, for example, whether the president or the Congress of People's Deputies would hold ultimate legislative authority. One of the few stipulations that was made was that a two-thirds vote in the Congress of People's Deputies had the power, only if such a vote were recommended by the newly created constitutional court, to remove the president if they violated the constitution, laws, or oath of office. Work on drafting a law to outline the presidency itself began on 24 April, with approximately two months until the inaugural holder was set to occupy the office. Under the initial draft the president was the chief executive in the RSFSR, but did not have the right to dismiss the Supreme Soviet or the Congress of People's Deputies or suspend their activities. The president could not be a people's deputy and, once elected, would have needed to suspend their membership in all political parties.

Now on 12 June 1991 first Russian presidential election in the country's history will take place, where the voters will decide the fate and future of Russia.

Last edited: