You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

A House Divided: A TL

- Thread starter Utgard96

- Start date

Looks like the British Isles and the Continent will have more common history.

Make me proud, Ernst August von Hannover.

Make me proud, Ernst August von Hannover.

RyanF

Banned

Evil Ernie on the throne, with the Great Famine a few years away...

Suppose one upside is if there is a Whig administration at the time they might make more of an effort to close the ports to exports like in the 1780s, if only because Augustus not wanting would convince them it's probably a good idea.

Suppose one upside is if there is a Whig administration at the time they might make more of an effort to close the ports to exports like in the 1780s, if only because Augustus not wanting would convince them it's probably a good idea.

I'm interested to see what effect this will have on Britain's overseas colonies. And the "Bloody Forties," sounds ominous.

Map of the United States, 1848

Mind if we see a map of TTL United States at this time?

This is as of the 1848 presidential election, but the only real changes from the TL's current state is that Florida, Iowa and Wisconsin have been admitted as states and Itasca and Cimarron Territories have been organized, so I don't think it's too spoilery.

Itasca Territory?

Named for Lake Itasca, positively identified as the source of the Mississippi River by Henry Rowe Schoolcraft's 1832 expedition. Interestingly, the lake was named by Schoolcraft himself, taking the last syllable of the Latin word "veritas" (truth) and the first syllable of the word "caput" (head); the idea was to convey that the lake was the "true head" of the river, so Itasca might pass into historical lore as the only state in the U.S. to have a name derived from Dog Latin.

I knew that, I'm just curious how it came to be known as that, rather than its OTL name.Named for Lake Itasca, positively identified as the source of the Mississippi River by Henry Rowe Schoolcraft's 1832 expedition. Interestingly, the lake was named by Schoolcraft himself, taking the last syllable of the Latin word "veritas" (truth) and the first syllable of the word "caput" (head); the idea was to convey that the lake was the "true head" of the river, so Itasca might pass into historical lore as the only state in the U.S. to have a name derived from Dog Latin.

I knew that, I'm just curious how it came to be known as that, rather than its OTL name.

Call it butterflies. Also the Minnesota River is close to the territory's southern border. Also also, @wilcoxchar used it in his TL (although in that the Minnesota River wasn't part of the territory at all) and I like the name.

I like it as a name, just curious. I feel really bad for the future Republic of Britain.

Does anybody live in Cimarron, by the way?

A couple of thousand homesteaders have crossed over from Arkansas, but overall it's the very frontier of American civilization at this point. By 1860 things will probably be different, if there was one thing southern agriculture was good at, it was expanding.

Huh, I had no idea that's where Itasca came from.Named for Lake Itasca, positively identified as the source of the Mississippi River by Henry Rowe Schoolcraft's 1832 expedition. Interestingly, the lake was named by Schoolcraft himself, taking the last syllable of the Latin word "veritas" (truth) and the first syllable of the word "caput" (head); the idea was to convey that the lake was the "true head" of the river, so Itasca might pass into historical lore as the only state in the U.S. to have a name derived from Dog Latin.

Also really enjoying this TL. Nice work!

#15: Banking on Success

A House Divided #15: Banking on Success

“Whatever policy we adopt, there must be an energetic prosecution of it. For this purpose it must be somebody's business to pursue and direct it incessantly.”

***

From “A History of the U.S. Economy, 1776-1976”

(c) 1979 by Professor Thomas Scotson (ed.)

Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press

Although Willie Mangum is an obscure President among the general public, even by 19th century standards, his legacy for the U.S. economy is far more significant than this would let on. He presided over the annexation of Texas and added four stars to the flag, more than any President since Monroe, kickstarting the second phase of westward expansion – the drive to the Pacific – which in turn created the longest economic boom in our history. He used the tariff passed by a friendly Congress in 1845 to create a funding program for internal improvements, which by this point mainly meant railroads, and many lines across the nation – not least the Union Pacific, our first transcontinental railroad – can credit this scheme alone for their successful completion. And last but definitely not least, it was under Mangum's administration that the Third Bank of the United States was created, a long-time goal of the Republican Party that only became realizable after the 1844 elections produced a majority for the party in both houses of Congress. Between them, these three actions can be credited with kickstarting the thirty-year period of constant economic growth that only ended with the Great Crash of 1874… [1]

***

From “Wheels of Steel: How North America Embraced the Rails”

(c) 1992 by James Manning

Chicago: Illinois United Writers

It is impossible to tell the story of rail in North America without mentioning the Baltimore and Ohio. Chartered in 1827 to carry freight across the Appalachians from Baltimore, Maryland to Wheeling, Virginia (as it then was), the B&O was the first true common carrier in the United States: that is, it was the first railroad whose charter required it to run regular services, accept all paying customers and assume financial responsibility for any cargo lost in transit. The reason for the B&O’s construction was simple: after the opening of the Erie Canal in 1821, New York received a major competitive advantage in trade between the growing western states and the outside world, and the other major cities along the East Coast were fearful of losing their economic lifeblood. In particular, Baltimore had previously had an edge over the other cities as a result of being located at the head of Chesapeake Bay, which meant its harbor was significantly further inland than others, requiring shorter distances transported overland – a great advantage in an era when the fastest and highest-capacity form of overland transportation was the horse-drawn carriage. When the Erie Canal opened, however, it suddenly became possible to get cargo all the way to Lake Erie without needing to move it overland a single foot, and Baltimore’s merchants feared that this would spell their end unless they could come up with a suitable alternative mode of transportation.

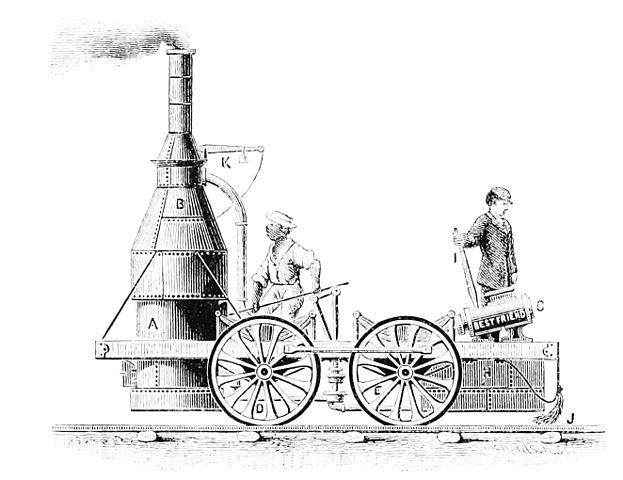

The founding of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad.

The answer came from England, where the world’s first public steam railroad had opened between the towns of Stockton and Darlington in 1825. News reached the U.S. not long after, and Baltimore residents Philip Thomas and George Brown sent a group led by Thomas’ brother Evan to investigate this new mode of transportation. They concluded that a railroad would be the perfect solution to Baltimore’s problems, and on February 12, 1827, a meeting of Baltimore notables signed an agreement founding the Baltimore and Ohio Rail Road Company. They obtained charters from the Maryland and Virginia legislatures within a month, and Thomas was appointed president of the company with Brown as its treasurer. Virtually every citizen of Baltimore bought stock in the B&O, whose total value approached three million dollars after a year of fundraising, and on Independence Day in 1828, the 91-year-old Charles Carroll of Carrollton, last surviving signer of the Declaration of Independence, conducted the groundbreaking ceremony for what may have been the boldest commercial venture in the young nation’s history. Constructing a railroad across the Appalachians would be a challenging proposition today, and we know where the Ohio River is, we know the lay of the intervening land, and we know how a railroad works. The closest one might get to an equivalent to the B&O today would be if Congress were to charter a corporation to provide regular freight service to the planet Mars. [2]

The first stretch of line, from Baltimore to Ellicott’s Mills on the Patapsco River, opened for business on May 24, 1830, and over the next four years the road was extended to Frederick (December 1831), Point of Rocks on the Potomac River (April 1832) and Sandy Hook, the location of the proposed Potomac crossing (December 1834). There, a legal dispute erupted between the B&O and the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal, whose owners wanted to exclude the railroad from its right of way, and it took until 1837 before the crossing to Harper’s Ferry, Virginia could finally be opened. By 1842 the B&O had reached Cumberland, where construction halted a second time before resuming in 1847, with the aid of Virginia’s share of Morehead funds, and in 1851 it finally reached Wheeling [3]. This was not to be the end of the railroad’s expansion, as it set its sights on what would become the hub of the nation’s transportation grid – Chicago, Illinois…

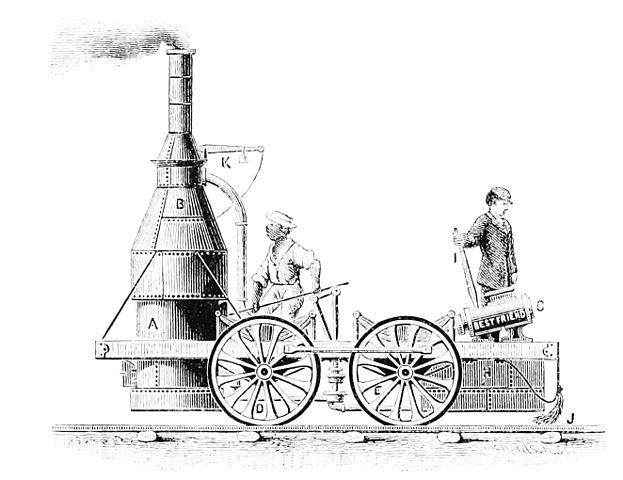

…The B&O is the most celebrated of America’s early railroads for a variety of reasons previously named, but contrary to the common conception it was not the first railroad to offer scheduled passenger service. That honor goes to the South Carolina Rail Road, now folded into the Great Southern system, which opened for business on Christmas Day 1830, after the B&O had opened its first line but before it had begun revenue passenger service. The SCRR was also the first railroad to use an entirely American-built locomotive, the Best Friend of Charleston, which served the line for six months before securing another first by being the first locomotive to fall victim to a boiler explosion on U.S. soil. The owners were not deterred by this, and in 1833 the railroad completed its intended mainline from Charleston to Hamburg, South Carolina, on the Savannah River. This route provided a shortcut for goods from the Upper South that would otherwise have been shipped through Savannah, Georgia, and earned Charleston its place as the South’s premier port into the bargain. Whereas most railroads in the North were constructed to the 4ft 8½in gauge in common usage in Europe, the SCRR was built to a broader gauge of five feet; other roads in the southern states would follow its example, thus giving rise to the division now existing across North America… [4]

Drawing of the Best Friend of Charleston. Note the slave shoveling coal into the boiler.

***

From “Henry Clay: Life of a Statesman”

(c) 1973 by Dr Adam Greene

New Orleans: Stephens & Co.

The 1844 elections, aside from returning Mangum in office as President, also saw huge strides for the Republicans on the congressional level. Both houses of the 29th Congress had Republican majorities, and for the first time ever this was combined with a Republican-held White House. Clay saw at long last the chance to implement the American System in full, and in this he had Mangum’s full cooperation. The first step in this was the Tariff of 1846, also known at the time as the “Black Tariff”, which increased tariff levels from roughly 25% under the Compromise Tariff of 1832 to an average of 37%. This passed through Congress on party-line votes, with a few southern Republicans voting against on conscience, but not enough to strike it down. Ultimately it had been expected given the victory of the Republicans that they’d pass a higher tariff, which may have contributed to the lack of serious opposition. More radical, however, was Clay’s proposal for what to do with the tariff revenue: an allocation of federal funds to subsidize railroad and canal construction.

Internal improvements had been a cornerstone of the American System for as long as the System had been in existence, but there was nonetheless segmented opposition to putting the funds into the hands of the federal government. Calhoun spoke against the idea in the Senate on March 4, 1846, calling it “the greatest intrusion upon the rights of the states to determine their own fate ever committed in the history of our republic”, and numerous less prominent southerners echoed his sentiments, including a large number of Republicans. Nonetheless, Clay was adamant, as were President Mangum and Daniel Webster, and positions appeared to be at a stalemate when Senator James Turner Morehead, Clay's Kentucky colleague, proposed a compromise: the establishment of a formula whereby the money allocated to internal improvements would be distributed among the states according to their census population and existing railroad and canal mileage. This, Morehead hoped, would target the funds toward spurring growth in the South and West rather than providing for the already well-developed rail system in the Northeast. Clay readily agreed to the idea, but Webster took some convincing before he went along with it – he was likely concerned that the small and highly developed New England states would lose out in the compromise. The Morehead Amendment, which set up the distribution formula, passed the Senate 27-22 with one absent member, and when the amended bill came before the House of Representatives it won broad approval and passed by a margin of 127-96…

James Turner Morehead.

…The 1847 session of Congress would prove even more controversial than that of the previous year. Most controversial of all was the Banking Act of 1847, which proposed to resurrect the old National Bank. If it had been proposed during the Harrison years, when the nation was in the throes of an economic crisis, it could’ve been passed very easily, but in the more prosperous 1840s the idea of regulating economic growth was an unappealing one. Nevertheless, Clay and Webster were adamant that the Bank must be resurrected before the end of the 29th Congress, the latter writing in his diary that “if our continued prosperity is to be secured, it is to be done now or never, for the vagaries of politics are such that we may never again enjoy the position we currently find ourselves in”. So the bill was introduced, and one of the oldest battles in American politics began again…

…The battle over the Bank is believed to have been the main contributing factor in the loss of the Republican House majority in the 1846 midterms, but the Bank itself grew increasingly popular over the remainder of Mangum’s term in office as the heightened tariffs resulted in a temporary loss of trade, which might have led to another economic crash had the Bank not helped redistribute financial resources toward the South. The relative quiet of the succeeding two decades, with the exception of the row over slavery in the early 1850s, can in part be attributed to the Bank’s stabilizing effect on the economy, and when its charter expired in 1867, just like that of the Second Bank it kicked off a speculation boom that ultimately led to the 1874 crash…

***

[1] IOTL, the U.S. economy was doing consistently fairly well in the 1850s and 1860s, with the obvious exception of the Civil War years – there were minor crises every few years as usual, but they were all quickly staved off, and the country didn't see a major economic depression until the Panic of 1873.

[2] The last two sentences are borrowed almost wholesale (it’s not plagiarism, it’s an homage) from Trains Magazine’s Historical Guide to North American Railroads, which I heartily recommend to anyone who wants to know more about the OTL history of rail transportation in the US.

[3] This is two years ahead of OTL.

[4] IOTL this was also the case, and a majority of southern railroads retained the 5ft gauge until the Civil War, when the breaks of gauge in Virginia and North Carolina wreaked havoc with the Confederacy’s logistics, ultimately leading to a system-wide regauging in 1886.

“Whatever policy we adopt, there must be an energetic prosecution of it. For this purpose it must be somebody's business to pursue and direct it incessantly.”

***

From “A History of the U.S. Economy, 1776-1976”

(c) 1979 by Professor Thomas Scotson (ed.)

Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press

Although Willie Mangum is an obscure President among the general public, even by 19th century standards, his legacy for the U.S. economy is far more significant than this would let on. He presided over the annexation of Texas and added four stars to the flag, more than any President since Monroe, kickstarting the second phase of westward expansion – the drive to the Pacific – which in turn created the longest economic boom in our history. He used the tariff passed by a friendly Congress in 1845 to create a funding program for internal improvements, which by this point mainly meant railroads, and many lines across the nation – not least the Union Pacific, our first transcontinental railroad – can credit this scheme alone for their successful completion. And last but definitely not least, it was under Mangum's administration that the Third Bank of the United States was created, a long-time goal of the Republican Party that only became realizable after the 1844 elections produced a majority for the party in both houses of Congress. Between them, these three actions can be credited with kickstarting the thirty-year period of constant economic growth that only ended with the Great Crash of 1874… [1]

***

From “Wheels of Steel: How North America Embraced the Rails”

(c) 1992 by James Manning

Chicago: Illinois United Writers

It is impossible to tell the story of rail in North America without mentioning the Baltimore and Ohio. Chartered in 1827 to carry freight across the Appalachians from Baltimore, Maryland to Wheeling, Virginia (as it then was), the B&O was the first true common carrier in the United States: that is, it was the first railroad whose charter required it to run regular services, accept all paying customers and assume financial responsibility for any cargo lost in transit. The reason for the B&O’s construction was simple: after the opening of the Erie Canal in 1821, New York received a major competitive advantage in trade between the growing western states and the outside world, and the other major cities along the East Coast were fearful of losing their economic lifeblood. In particular, Baltimore had previously had an edge over the other cities as a result of being located at the head of Chesapeake Bay, which meant its harbor was significantly further inland than others, requiring shorter distances transported overland – a great advantage in an era when the fastest and highest-capacity form of overland transportation was the horse-drawn carriage. When the Erie Canal opened, however, it suddenly became possible to get cargo all the way to Lake Erie without needing to move it overland a single foot, and Baltimore’s merchants feared that this would spell their end unless they could come up with a suitable alternative mode of transportation.

The founding of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad.

The answer came from England, where the world’s first public steam railroad had opened between the towns of Stockton and Darlington in 1825. News reached the U.S. not long after, and Baltimore residents Philip Thomas and George Brown sent a group led by Thomas’ brother Evan to investigate this new mode of transportation. They concluded that a railroad would be the perfect solution to Baltimore’s problems, and on February 12, 1827, a meeting of Baltimore notables signed an agreement founding the Baltimore and Ohio Rail Road Company. They obtained charters from the Maryland and Virginia legislatures within a month, and Thomas was appointed president of the company with Brown as its treasurer. Virtually every citizen of Baltimore bought stock in the B&O, whose total value approached three million dollars after a year of fundraising, and on Independence Day in 1828, the 91-year-old Charles Carroll of Carrollton, last surviving signer of the Declaration of Independence, conducted the groundbreaking ceremony for what may have been the boldest commercial venture in the young nation’s history. Constructing a railroad across the Appalachians would be a challenging proposition today, and we know where the Ohio River is, we know the lay of the intervening land, and we know how a railroad works. The closest one might get to an equivalent to the B&O today would be if Congress were to charter a corporation to provide regular freight service to the planet Mars. [2]

The first stretch of line, from Baltimore to Ellicott’s Mills on the Patapsco River, opened for business on May 24, 1830, and over the next four years the road was extended to Frederick (December 1831), Point of Rocks on the Potomac River (April 1832) and Sandy Hook, the location of the proposed Potomac crossing (December 1834). There, a legal dispute erupted between the B&O and the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal, whose owners wanted to exclude the railroad from its right of way, and it took until 1837 before the crossing to Harper’s Ferry, Virginia could finally be opened. By 1842 the B&O had reached Cumberland, where construction halted a second time before resuming in 1847, with the aid of Virginia’s share of Morehead funds, and in 1851 it finally reached Wheeling [3]. This was not to be the end of the railroad’s expansion, as it set its sights on what would become the hub of the nation’s transportation grid – Chicago, Illinois…

…The B&O is the most celebrated of America’s early railroads for a variety of reasons previously named, but contrary to the common conception it was not the first railroad to offer scheduled passenger service. That honor goes to the South Carolina Rail Road, now folded into the Great Southern system, which opened for business on Christmas Day 1830, after the B&O had opened its first line but before it had begun revenue passenger service. The SCRR was also the first railroad to use an entirely American-built locomotive, the Best Friend of Charleston, which served the line for six months before securing another first by being the first locomotive to fall victim to a boiler explosion on U.S. soil. The owners were not deterred by this, and in 1833 the railroad completed its intended mainline from Charleston to Hamburg, South Carolina, on the Savannah River. This route provided a shortcut for goods from the Upper South that would otherwise have been shipped through Savannah, Georgia, and earned Charleston its place as the South’s premier port into the bargain. Whereas most railroads in the North were constructed to the 4ft 8½in gauge in common usage in Europe, the SCRR was built to a broader gauge of five feet; other roads in the southern states would follow its example, thus giving rise to the division now existing across North America… [4]

Drawing of the Best Friend of Charleston. Note the slave shoveling coal into the boiler.

***

From “Henry Clay: Life of a Statesman”

(c) 1973 by Dr Adam Greene

New Orleans: Stephens & Co.

The 1844 elections, aside from returning Mangum in office as President, also saw huge strides for the Republicans on the congressional level. Both houses of the 29th Congress had Republican majorities, and for the first time ever this was combined with a Republican-held White House. Clay saw at long last the chance to implement the American System in full, and in this he had Mangum’s full cooperation. The first step in this was the Tariff of 1846, also known at the time as the “Black Tariff”, which increased tariff levels from roughly 25% under the Compromise Tariff of 1832 to an average of 37%. This passed through Congress on party-line votes, with a few southern Republicans voting against on conscience, but not enough to strike it down. Ultimately it had been expected given the victory of the Republicans that they’d pass a higher tariff, which may have contributed to the lack of serious opposition. More radical, however, was Clay’s proposal for what to do with the tariff revenue: an allocation of federal funds to subsidize railroad and canal construction.

Internal improvements had been a cornerstone of the American System for as long as the System had been in existence, but there was nonetheless segmented opposition to putting the funds into the hands of the federal government. Calhoun spoke against the idea in the Senate on March 4, 1846, calling it “the greatest intrusion upon the rights of the states to determine their own fate ever committed in the history of our republic”, and numerous less prominent southerners echoed his sentiments, including a large number of Republicans. Nonetheless, Clay was adamant, as were President Mangum and Daniel Webster, and positions appeared to be at a stalemate when Senator James Turner Morehead, Clay's Kentucky colleague, proposed a compromise: the establishment of a formula whereby the money allocated to internal improvements would be distributed among the states according to their census population and existing railroad and canal mileage. This, Morehead hoped, would target the funds toward spurring growth in the South and West rather than providing for the already well-developed rail system in the Northeast. Clay readily agreed to the idea, but Webster took some convincing before he went along with it – he was likely concerned that the small and highly developed New England states would lose out in the compromise. The Morehead Amendment, which set up the distribution formula, passed the Senate 27-22 with one absent member, and when the amended bill came before the House of Representatives it won broad approval and passed by a margin of 127-96…

James Turner Morehead.

…The 1847 session of Congress would prove even more controversial than that of the previous year. Most controversial of all was the Banking Act of 1847, which proposed to resurrect the old National Bank. If it had been proposed during the Harrison years, when the nation was in the throes of an economic crisis, it could’ve been passed very easily, but in the more prosperous 1840s the idea of regulating economic growth was an unappealing one. Nevertheless, Clay and Webster were adamant that the Bank must be resurrected before the end of the 29th Congress, the latter writing in his diary that “if our continued prosperity is to be secured, it is to be done now or never, for the vagaries of politics are such that we may never again enjoy the position we currently find ourselves in”. So the bill was introduced, and one of the oldest battles in American politics began again…

…The battle over the Bank is believed to have been the main contributing factor in the loss of the Republican House majority in the 1846 midterms, but the Bank itself grew increasingly popular over the remainder of Mangum’s term in office as the heightened tariffs resulted in a temporary loss of trade, which might have led to another economic crash had the Bank not helped redistribute financial resources toward the South. The relative quiet of the succeeding two decades, with the exception of the row over slavery in the early 1850s, can in part be attributed to the Bank’s stabilizing effect on the economy, and when its charter expired in 1867, just like that of the Second Bank it kicked off a speculation boom that ultimately led to the 1874 crash…

***

[1] IOTL, the U.S. economy was doing consistently fairly well in the 1850s and 1860s, with the obvious exception of the Civil War years – there were minor crises every few years as usual, but they were all quickly staved off, and the country didn't see a major economic depression until the Panic of 1873.

[2] The last two sentences are borrowed almost wholesale (it’s not plagiarism, it’s an homage) from Trains Magazine’s Historical Guide to North American Railroads, which I heartily recommend to anyone who wants to know more about the OTL history of rail transportation in the US.

[3] This is two years ahead of OTL.

[4] IOTL this was also the case, and a majority of southern railroads retained the 5ft gauge until the Civil War, when the breaks of gauge in Virginia and North Carolina wreaked havoc with the Confederacy’s logistics, ultimately leading to a system-wide regauging in 1886.

Last edited:

Alex Richards

Donor

Interesting, all of this suggests that the Civil War will be later and a very different beast.

I don't think a lack of Civil War would lead to a break of gauge across across North America. I only think a Southern Victory would do so. A coast to coast railroad even to Oregon would still be wanted, and thus would end up on Northern gauge. Anyone know of the factors and time period when the Mexicans got onto the same gauge as the United States? (OTL, Canada, the US and Mexico are all the same gauge.)

I don't think a lack of Civil War would lead to a break of gauge across across North America. I only think a Southern Victory would do so. A coast to coast railroad even to Oregon would still be wanted, and thus would end up on Northern gauge.

I agree that the US would inevitably standardize gauges on the vast majority of its lines.

Anyone know of the factors and time period when the Mexicans got onto the same gauge as the United States? (OTL, Canada, the US and Mexico are all the same gauge.)

Canada went from 5'6" to standard gauge in 1873, Mexico is very hard to find good information about.

Share: