#6: Nullification Blues

A House Divided #6: Nullification Blues

“The Government of the absolute majority instead of the Government of the people is but the Government of the strongest interests; and when not efficiently checked, it is the most tyrannical and oppressive that can be devised.”

***

From “Waxhaws to White House: The Life and Times of Andrew Jackson”

(c) 1962 by Dr Josiah Harris

Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press

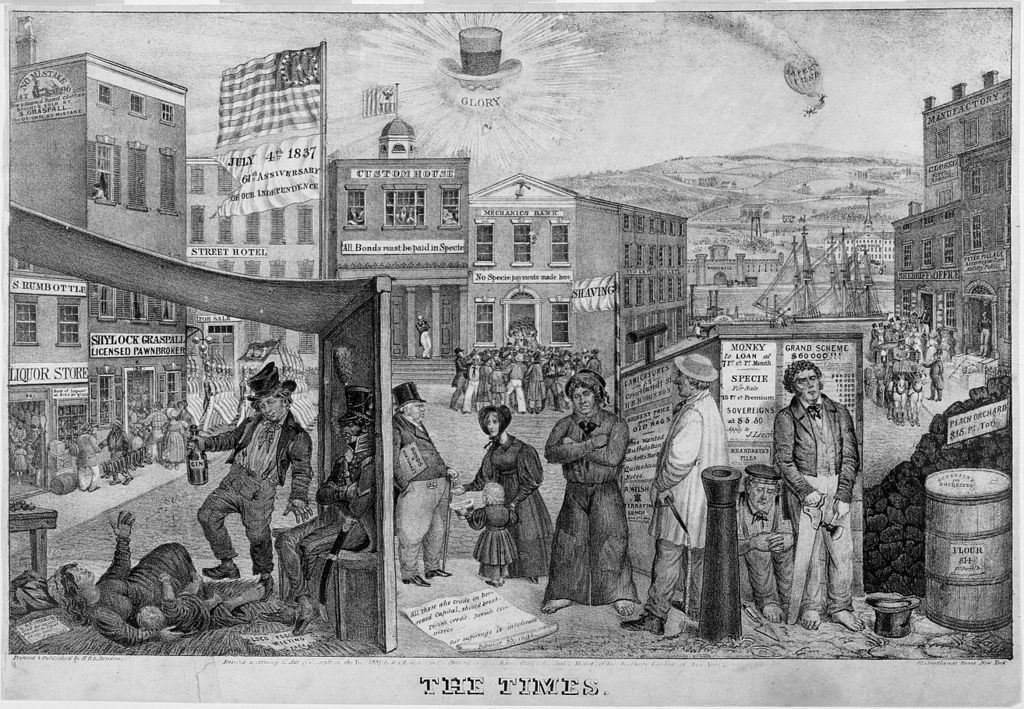

…The greatest test to Jackson's administration came on the issue of tariffs, which would come to be a dominant theme in economic policy during his period in office. The 1820s were a decade of general economic stagnation for the US, and to protect domestic industry, John Quincy Adams had signed into law the Tariff of 1828, which set the highest import rates in US history on industrial goods as well as a number of raw materials. This helped the North recover somewhat – the nationwide GDP grew significantly between 1828 and 1832, mostly spurred by northern industrial growth – but was a complete economic disaster for the South, whose economy was dependent on access to foreign trade. Where the North was able to rise from the ashes, the South appeared to spiral further into economic malaise, and during Jackson's election campaign in 1828, a number of southern Jackson supporters pledged to repeal the tariff once Jackson had been elected. Jackson himself appears not to have noticed or cared about these pledges made on his behalf, because in his first year in office, no action whatsoever had been taken against the tariff…

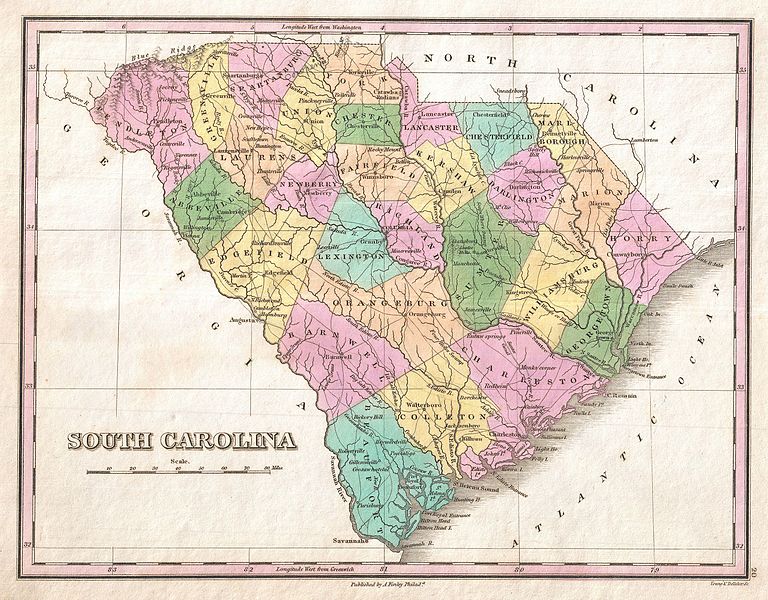

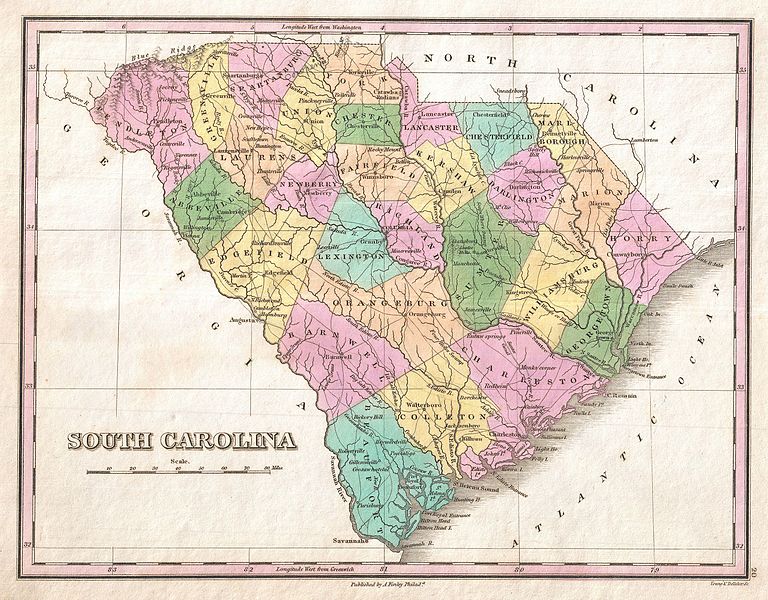

…It was particularly in South Carolina that anti-tariff sentiment ran high. Incidentally, it was of course South Carolina that was home to the Vice President, John Caldwell Calhoun, who penned the “Exposition and Protest” in December of 1828. The Exposition argued that the tariff was unconstitutional, because its purpose was not to provide general revenue but overtly to favor one sector of the economy (industry) over another (agriculture). Moreover, the Exposition argued that it was perfectly within the bounds of legality for a state, having discussed the matter at a duly elected convention, had the right to nullify within its boundaries any federal law it felt violated the Constitution. This nullification doctrine had previously been set out by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison in their protest against the Alien and Sedition Acts, and was a cornerstone of the political philosophy devised by Jefferson and John Randolph, among others. Calhoun saw to it that the Exposition was published anonymously, fearing a break with Jackson might hurt his cause more than it would help, but word of the author's identity soon got out.

The publication of the Exposition reignited the debate over nullification in Washington and across the country. This debate essentially hinged on one's view of the origins of the Constitution and by extension, the federal government – nationalists like Daniel Webster and John Quincy Adams argued that the Constitution was the product of the American people as a whole, while men like Calhoun and Randolph argued that it was a compact between sovereign states, which could decide for themselves what was and wasn't constitutional. Its clearest iteration can be found in a Senate debate between Daniel Webster and Robert Hayne, held in January of 1830, which began when Hayne rose in opposition to a resolution proposed by Senator Samuel Foot of Connecticut, that would have severely restricted the states' power to sell frontier land. This, Hayne felt, constituted a transgression of states' rights, and he attempted to create a South-West alliance against the Eastern states by linking the issue to that of nullification. Webster rose in opposition to this, and the two men had a long series of exchanges that have been recognized as “the most celebrated debate in the Senate's history”. Webster notably created something of a slogan for the nationalists when, in his second reply to Hayne, he referred to the federal government as being “made by the people, made for the people, and answerable to the people”…

…President Jackson first began to hint at his views on nullification when, at the traditional celebration of Jefferson's birthday held by the Democratic Party every year in April, a “battle of toasts” erupted between the party's factions. Hayne proposed a toast to “the Union of the States, and the Sovereignty of the States”, to which Jackson replied by toasting “our Federal Union: it must be preserved”. Then-Senator Benton would write in his memoirs that Jackson's toast “electrified the country”, and from that moment, battle lines appeared to be getting drawn. Certainly Jackson did not try to back down from his position – when asked if he had a message for the people of South Carolina by a visitor from that state, he replied: “Please give my compliments to my friends in your State and say to them, that if a single drop of blood shall be shed there in opposition to the laws of the United States, I will hang the first man I can lay my hand on engaged in such treasonable conduct, upon the first tree I can reach”… [1]

…Perhaps understandably, tensions continued to rise in South Carolina, where the October legislative elections would prove something of a turning point. The increasingly organized “Nullifier party” made it known that they would use any mandate gained in the elections to call a state convention to debate nullification, and anti-nullification groups united in opposition to this. The Nullifiers won a fairly strong majority, and were able to elect the radical Nullifier James Hamilton, Jr. to the governor's office. However, the Nullifier majority fell short of the two thirds required to call a state convention, and so the issue lingered for two more years…

…The 1832 South Carolina elections were held just weeks before that year's presidential election, and saw the nullifiers and anti-nullifiers (or “Unionists”) campaign as organized parties for the first time. The Unionists campaigned to re-elect Jackson to the presidency in tandem with their state campaign, but the Nullifiers did not put much effort into national politics, only letting it be known that a Nullifier legislature would send an electoral slate supporting neither Jackson nor Clay. Ultimately the Nullifiers ended up winning a landslide, and took control of both houses of the legislature with supermajorities large enough to call a convention. Promptly, the legislature was called into session to authorize the convention, and the latter assembled in November of 1832 to hear the case for and against nullification and make a decision for the people of the state. With a large majority of delegates being committed Nullifiers, there was little doubt which way the vote would go. The resolution approved by the convention stated that the tariff of 1828 was in violation of the Constitution, that its enforcement within the state was prohibited from 1833 onwards, and that in case the federal government should attempt to impose its will by force, the governor was authorized to raise and arm a militia of 25,000 men. [2]

Before then, however, Congress had reassembled in Washington, and preventing nullification was the first point on its agenda. Henry Clay and John Calhoun, both now Senators (after Robert Hayne's election as Governor, Calhoun had resigned from the Vice Presidency to take his seat, leaving the latter office vacant), managed to find rare common ground in the desire to embarrass Jackson by resolving the crisis without his intervention, and together the two drafted a new tariff bill which lowered export duties on agricultural products from an average of 45% in the 1828 tariff to an average of 30%. This was rushed through Congress and passed by broad margins in both houses, including the South Carolina Nullifiers (who likely would've preferred to see the duties go down even further, but deferred to Calhoun) and a substantial number of Jacksonians as well as the Republicans who Clay managed to whip with great acumen. Within two weeks of the new year, the tariff was passed, and while Jackson could have vetoed it, he saw no need to look a gift horse in the mouth. The Tariff of 1833 went into effect on March 1, and South Carolina promptly demurred. The Nullification Crisis, at least for the time being, was over… [3]

***

Excerpts from a discussion at fc/gen/uchronia, labeled “WI: South Carolina secedes during Nullification Crisis?”

[1] Jackson said this IOTL as well. That man was not the sort to mince words, to say the least.

[2] My description of the Nullification Crisis up to this point is more or less entirely OTL.

[3] At this point things diverge somewhat – the Republicans, having been energized by Taney's anti-Bank shenanigans, are sufficiently willing to put egg on Jackson's face to agree to a compromise tariff before the Force Bill is floated.

“The Government of the absolute majority instead of the Government of the people is but the Government of the strongest interests; and when not efficiently checked, it is the most tyrannical and oppressive that can be devised.”

***

From “Waxhaws to White House: The Life and Times of Andrew Jackson”

(c) 1962 by Dr Josiah Harris

Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press

…The greatest test to Jackson's administration came on the issue of tariffs, which would come to be a dominant theme in economic policy during his period in office. The 1820s were a decade of general economic stagnation for the US, and to protect domestic industry, John Quincy Adams had signed into law the Tariff of 1828, which set the highest import rates in US history on industrial goods as well as a number of raw materials. This helped the North recover somewhat – the nationwide GDP grew significantly between 1828 and 1832, mostly spurred by northern industrial growth – but was a complete economic disaster for the South, whose economy was dependent on access to foreign trade. Where the North was able to rise from the ashes, the South appeared to spiral further into economic malaise, and during Jackson's election campaign in 1828, a number of southern Jackson supporters pledged to repeal the tariff once Jackson had been elected. Jackson himself appears not to have noticed or cared about these pledges made on his behalf, because in his first year in office, no action whatsoever had been taken against the tariff…

…It was particularly in South Carolina that anti-tariff sentiment ran high. Incidentally, it was of course South Carolina that was home to the Vice President, John Caldwell Calhoun, who penned the “Exposition and Protest” in December of 1828. The Exposition argued that the tariff was unconstitutional, because its purpose was not to provide general revenue but overtly to favor one sector of the economy (industry) over another (agriculture). Moreover, the Exposition argued that it was perfectly within the bounds of legality for a state, having discussed the matter at a duly elected convention, had the right to nullify within its boundaries any federal law it felt violated the Constitution. This nullification doctrine had previously been set out by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison in their protest against the Alien and Sedition Acts, and was a cornerstone of the political philosophy devised by Jefferson and John Randolph, among others. Calhoun saw to it that the Exposition was published anonymously, fearing a break with Jackson might hurt his cause more than it would help, but word of the author's identity soon got out.

The publication of the Exposition reignited the debate over nullification in Washington and across the country. This debate essentially hinged on one's view of the origins of the Constitution and by extension, the federal government – nationalists like Daniel Webster and John Quincy Adams argued that the Constitution was the product of the American people as a whole, while men like Calhoun and Randolph argued that it was a compact between sovereign states, which could decide for themselves what was and wasn't constitutional. Its clearest iteration can be found in a Senate debate between Daniel Webster and Robert Hayne, held in January of 1830, which began when Hayne rose in opposition to a resolution proposed by Senator Samuel Foot of Connecticut, that would have severely restricted the states' power to sell frontier land. This, Hayne felt, constituted a transgression of states' rights, and he attempted to create a South-West alliance against the Eastern states by linking the issue to that of nullification. Webster rose in opposition to this, and the two men had a long series of exchanges that have been recognized as “the most celebrated debate in the Senate's history”. Webster notably created something of a slogan for the nationalists when, in his second reply to Hayne, he referred to the federal government as being “made by the people, made for the people, and answerable to the people”…

…President Jackson first began to hint at his views on nullification when, at the traditional celebration of Jefferson's birthday held by the Democratic Party every year in April, a “battle of toasts” erupted between the party's factions. Hayne proposed a toast to “the Union of the States, and the Sovereignty of the States”, to which Jackson replied by toasting “our Federal Union: it must be preserved”. Then-Senator Benton would write in his memoirs that Jackson's toast “electrified the country”, and from that moment, battle lines appeared to be getting drawn. Certainly Jackson did not try to back down from his position – when asked if he had a message for the people of South Carolina by a visitor from that state, he replied: “Please give my compliments to my friends in your State and say to them, that if a single drop of blood shall be shed there in opposition to the laws of the United States, I will hang the first man I can lay my hand on engaged in such treasonable conduct, upon the first tree I can reach”… [1]

…Perhaps understandably, tensions continued to rise in South Carolina, where the October legislative elections would prove something of a turning point. The increasingly organized “Nullifier party” made it known that they would use any mandate gained in the elections to call a state convention to debate nullification, and anti-nullification groups united in opposition to this. The Nullifiers won a fairly strong majority, and were able to elect the radical Nullifier James Hamilton, Jr. to the governor's office. However, the Nullifier majority fell short of the two thirds required to call a state convention, and so the issue lingered for two more years…

…The 1832 South Carolina elections were held just weeks before that year's presidential election, and saw the nullifiers and anti-nullifiers (or “Unionists”) campaign as organized parties for the first time. The Unionists campaigned to re-elect Jackson to the presidency in tandem with their state campaign, but the Nullifiers did not put much effort into national politics, only letting it be known that a Nullifier legislature would send an electoral slate supporting neither Jackson nor Clay. Ultimately the Nullifiers ended up winning a landslide, and took control of both houses of the legislature with supermajorities large enough to call a convention. Promptly, the legislature was called into session to authorize the convention, and the latter assembled in November of 1832 to hear the case for and against nullification and make a decision for the people of the state. With a large majority of delegates being committed Nullifiers, there was little doubt which way the vote would go. The resolution approved by the convention stated that the tariff of 1828 was in violation of the Constitution, that its enforcement within the state was prohibited from 1833 onwards, and that in case the federal government should attempt to impose its will by force, the governor was authorized to raise and arm a militia of 25,000 men. [2]

Before then, however, Congress had reassembled in Washington, and preventing nullification was the first point on its agenda. Henry Clay and John Calhoun, both now Senators (after Robert Hayne's election as Governor, Calhoun had resigned from the Vice Presidency to take his seat, leaving the latter office vacant), managed to find rare common ground in the desire to embarrass Jackson by resolving the crisis without his intervention, and together the two drafted a new tariff bill which lowered export duties on agricultural products from an average of 45% in the 1828 tariff to an average of 30%. This was rushed through Congress and passed by broad margins in both houses, including the South Carolina Nullifiers (who likely would've preferred to see the duties go down even further, but deferred to Calhoun) and a substantial number of Jacksonians as well as the Republicans who Clay managed to whip with great acumen. Within two weeks of the new year, the tariff was passed, and while Jackson could have vetoed it, he saw no need to look a gift horse in the mouth. The Tariff of 1833 went into effect on March 1, and South Carolina promptly demurred. The Nullification Crisis, at least for the time being, was over… [3]

***

Excerpts from a discussion at fc/gen/uchronia, labeled “WI: South Carolina secedes during Nullification Crisis?”

1990-04-02 18:19 EST, @MikeOfThePlatte wrote:

I recently read a biography on Andrew Jackson, and I came across an interesting potential divergence: As most of us no doubt know, South Carolina tried to nullify the Tariff of 1828, and it took Calhoun and Clay working together to pass a new compromise tariff before they backed down. But did you know that South Carolina actually had plans to secede and raise a militia if the government didn't let them go ahead with nullification?

1990-04-02 18:21 EST, @YosemiteSam wrote:

Oh, it went above and beyond that. Jackson was clearly raring to fight them all throughout, and in fact, at the time the Compromise Tariff was going through the House, he was planning to introduce a bill that would've let him send federal troops into South Carolina to enforce the tariff and strike down opposition to it. If the Compromise Tariff had even been delayed by, say, three months, then things could've turned very ugly indeed.

1990-04-02 18:29 EST, @MikeOfThePlatte wrote:

Fascinating. So if Jackson had stood his ground and Clay his, could we have seen a southern secession?

1990-04-02 18:33 EST, @AgentBlue wrote:

Not this goddamn southern secession trope again. The South was clearly favored by Washington throughout the First Republic – just look at the way it kowtowed to slaveholding interests over Mexico, or *New* Mexico, or the transcontinental railroad, or Kansas. They'd have very little to gain by seceding from a country that let them be on top when the North had twice their population.

1990-04-02 18:36 EST, @YosemiteSam wrote:

Well @MikeOfThePlatte, I don't know about the South as a whole, but South Carolina very definitely could've seceded. Feelings were running very high on both sides throughout the affair, and as you say, the nullification convention did enable the governor to raise a militia to defend the state from any and all comers (read: any federal troops Jackson might send their way). Any attempt by South Carolina to leave the Union on its own would've led to a very short war, and most of the other southern states, while they weren't happy about the tariff, didn't go so far as to try to nullify it, and probably wouldn't have been inclined to walk out of the Union on South Carolina's word. So their only hope in case of secession would've been if Washington would've let them go peacefully, which knowing Jackson… yeah, no.

1990-04-02 18:43 EST, @sonofliberty wrote:

Even if South Carolina couldn't have *successfully* seceded, there's still an interesting scenario to be had here. Say they do secede, Jackson does send in the troops, and the tariff of 1828 is forcibly imposed on the South. IOW, the issue died down pretty quickly after South Carolina managed to more or less force its will on Washington by way of threats, and the federal government more or less demurred from protectionism until […] But if the federal government had instead established a precedent of forcing its will on individual states, I imagine things could've turned out very different. Imagine if Jackson, spurred by his successful defense of the Union, would've used the occasion to push forward with the abolition of the Electoral College, as he wanted to do. I think the whole Southern dominance of Washington that @AgentBlue spoke of (not wrongly) could've been… not averted, but very much lessened in such a scenario. Hell, if the North gets its act together and produces a consolidated political platform, we could even see slavery abolished by, say, 1865 in such a scenario.

***1990-04-02 18:50 EST, @YosemiteSam wrote:

What? I got what you were saying with that post, and even broadly agreed, until the last sentence. What “unified northern agenda” could've done that so quickly? The North was always disunited politically during the First Republic, otherwise every presidential election would've been lopsided. Plus it had more than a few active supporters of slavery, and probably a majority of people who didn't care either way and just wanted economic prosperity. If such a “Northern Party” were to arise, I refuse to believe it could *both* be openly abolitionist *and* maintain its broad support from across the free states.

[1] Jackson said this IOTL as well. That man was not the sort to mince words, to say the least.

[2] My description of the Nullification Crisis up to this point is more or less entirely OTL.

[3] At this point things diverge somewhat – the Republicans, having been energized by Taney's anti-Bank shenanigans, are sufficiently willing to put egg on Jackson's face to agree to a compromise tariff before the Force Bill is floated.

Last edited: