Chapter Five – The Free State Years

John Meredith (1868-1937)

Meredith spent his first term as Chief Minister setting up his new country. It was agreed that there was to be 9 members of the Cabinet – the Chief Minister and President, of course, would be joined by Ministers of Finance, Defence, Foreign Affairs, Interior, Mining, Native Affairs and Agriculture and Fishing. The Alaskan Party held all those roles except President, held by Plaid, and Native Affairs, held by an independent Tagish assemblyman. The Minister of the Interior, Michael James, was given the title of Deputy Minister, the designated successor to the Chief Minister.

Meredith also encouraged immigration to help Alaska's growth. Between 1911 and 1916, the population grew by an estimated 15,000. Though there was more immigration from the US, Canada and Wales, many of those new immigrants were Japanese. Japan desired control over the Aleutians, so they asked the Alaskan government for permission to settle a number of immigrants in those islands, which were purely inhabited by the native Aleuts at that point, since the Russians had all left. Meredith wanted to keep friendly relations with all the local powers, to expand control over the Aleutians, and to grow the population, so he consented.

Most of the Japanese moved into the settlement of Unalaska, where the Russians had built an Orthodox church, both for themselves and the Aleuts, who has converted. Many of the Japanese converted to Russian Orthodoxy too.

With Japanese assistance, Alaska trained a small militia of a thousand men, called the Alaskan Regiment, and converted some trawlers until patrol ships. This cooperation with Japan made Britain worry about Japan's influence on Alaska, so they responded by reaching out to the Welsh Alaskans.

In the 1910s, the Welsh Alaskans were doing rather well. They dominated Trelew, owning most of the saloons and the docks, as well as having many seats on the Council and the Mayorship. The first cars in Alaska were brought over by Dafydd Jenkins, a Welsh businessman who established Jenkins Automobiles, which still exists today. The Welsh Nationalists were now a minority as most of the community supported the moderates led by President John.

Therefore, Britain’s efforts came to naught. They then courted the Union Party, who happily received them. During the Jenkins Presidency, the Alaskan Party evolved into a liberal, pro-Japan, pro-independence party occupying the centre to centre-left of the political spectrum. The Union Party became a conservative, pro-Britain, pro-annexation party occupying the centre-right.

In 1916, the second elections were held. The Union Party were major gainers, having gotten 11 more seats (all 5 American Party seats and 6 from the Alaskan Party), while Plaid and the Independents kept the same number of seats. The composition was then 48 seats for the Alaskan Party, 21 for the Union Party, 9 for Plaid and 2 Independents. Meredith and John both kept their jobs.

In his second term, Meredith decided to open up Alaska to gambling. Trelew and Porth Madryn became famous for their casinos, most famously Casino Crand (Grand Casino) by the river. It was such a famous gambling haven that, The Welsh Casino, the first of the famous John Black spy series by Ian Fleming was set in Trelew.

These reforms weren’t popular among the many Methodists and Orthodox Christians, especially the clergy. This led to a famous meeting between Reverend Llewellyn Roberts, the most prominent Methodist Minister in Alaska and a Welsh Nationalist, and Mikhail, Bishop of Alyeska, in Matsukov. They agreed that a combined Christian front against immorality was needed, so the United Christian Party was formed. To avoid violating the separation of church and state, which was enshrined in the Constitution, a devout Methodist, Michael Williams, and a devout Orthodox, Grigori Petrov, were appointed as co-chairmen. However, the real power lay with Roberts and Mikhail.

Alaska prospered, so the population increased yet again to around 84,000. Of this, around 35,000 were Canadian, English, Irish or Scottish in origin, 16,000 were American in origin, 12,000 were Native Alaskan in Origin, 10,000 were Russian in origin, 9,000 were Welsh in origin and 2,000 were Japanese in origin.

Before the 1921 elections, Meredith and the Alaskan Party decided to grant all the Natives, Russians and Japanese citizenship and suffrage, hoping to gain their votes. The 1921 Election, saw the Alaskan Party lose their majority for the first time, as they won 28 seats, the Union Party won 22, the United Christians won 14, Plaid Cymraeg won 7, Native Independents won 6 and the Russian Bloc (a secular Russian party) won 3. The AP managed to secure a third term in government thanks to a coalition with Plaid and supply and demand from the Natives, but Meredith resigned as Leader. He was replaced by Edward Patrick, a more moderate figure. William John was reappointed as President, which was part of the deal with Plaid.

Patrick decided to continue developing Alaska and encouraging immigration, most of which came from Canada and Japan. As Japan was asserting itself more and more aggressively during this time, he came under increasing pressure from both Tokyo and Ottawa to choose a side. Instead, he initiated the Peaceful Neutrality stance, in contrast to the Armed Neutrality of Switzerland. He kept good relations with both Japan and Britain/Canada but refrained from going with one side definitively. This led to a split in the Alaskan Party. Patrickists supported his neutrality doctrine, while Nipponists favoured a Pro-Japan foreign policy and Canadists favoured a Pro-Canadian foreign policy. These divisions became irreparable and led to the shattering of the Alaskan Party in 1924, an event which caused major changes to Alaskan politics.

Patrick lost a vote of no confidence, leading to snap elections being called. This resulted in a complete mess of an Assembly. Union got the most seats with 21, while the United Christians got 16, the rump AP got 11, the New Alaskans (Nipponites) got 9, Plaid got 8, the Alaskan Alliance (Canadists) got 7, Native Independents got 7 and the Russian Bloc got 1.

A coalition between Union, the United Christians and the Alaskan Alliance was formed. George Farr was elected Chief Minister, with Joseph W. Parsons appointed President. However, the Unionists and Christians had different priorities. Complicating the situation were internal disagreements between Methodists and Orthodox in the UCP. Therefore, Farr couldn’t get anything done before the 1926 Elections, which caused even more mess.

The Christians were the largest party with 16, while both AP and Union had 15, the newly formed Radical Party had 13, Plaid had 9, Native Independents had 7 and the Alaskan Alliance had 5. Coalition negotiations broke down, and everyone wanted to keep the Radicals out of government, so a Popular Front grand coalition was agreed between the UCP, AP, Union, Plaid and AA. Michael Williams was elected Chief Minister, while John Meredith was appointed President as he was a unifying figure.

The Popular Front was unstable but held together, managing to chart a neutral foreign policy while increasing the military to 5,000, with 2,000 of them professional, and securing both Japanese and British military training. They also increased the economy by exporting gold, but that all came to an end with the Great Depression.

With the gold trade drying up, the economy evaporated, and with it the government’s popularity. Miner strikes were common as the popularity of the Radical Party soared, leading to the Popular Front agreeing to an electoral pact for the 1931 Elections. Opposed mainly by the Radicals, the election was close fought but the Radicals managed to eke out a victory with 43 seats, compared to 30 for the Popular Front and 7 for the Natives.

The new Chief Minister was Edwin Burrow, who appointed Welsh Socialist Rhodri Evans as President. They passed laws protecting the Tribes, leading to all of the Native Representatives joining their party. They also enacted welfare and other Keynesian policies to help ease the Great Depression. They were moderately successfully but Alaska became indebted to foreign powers. In foreign affairs, Burrow charted a neutral course that failed to please either Canada or Japan.

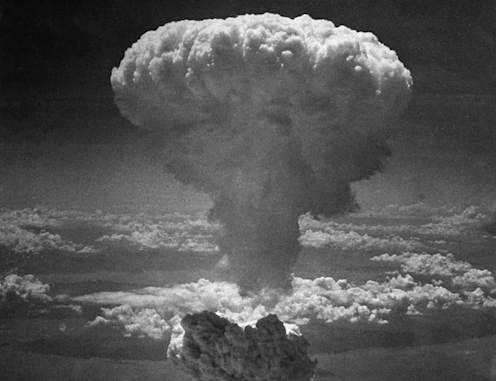

Japan in the early 1930s was getting increasingly militaristic. The militarists were buoyed by the gain of the Russian Far East, which was achieved in the Great European War, they set their sights on Qing China. With tensions growing between the two Asian nations, a supposed Chinese spy assassinating a General was deemed a suitable casus belli. Japan declared war on June 1st 1932, a date which is now considered the start of the Pacific War.

The modern Imperial Japanese Army demolished the out dated Chinese Army and took Manchuria without much hassle, pushing onto Beijing, which fell in 1934. This led to the Qing imploding, as their heartland was occupied, and the Fragmentation of China began. As Japan began to get bogged down in a widening front, they looked elsewhere for gains. An embargo by America meant that they were running out of oil, a crucial resource. The IJA and IJN decided that a coup de grace attack on the Dutch East Indies should secure a reliable oil supply.

The attack was a complete disaster. Japan had overstretched itself, and British code breakers had found out about the attack beforehand, immediately informing the Dutch. This brought the Netherlands into the war, and Britain and France, who wanted to contain Japanese expansion, too. The Pacific War had truly begun.

...

I hope this is a nice Christmas present for you all! Unfortunately progress on this TL stopped but as there is not much left I'm bringing it back with the aim of finishing it by the end of January.