His Martian novels were published in 1908-1912. Lenin used to joke about them.Alexander Bogdanov is a figure of the 20s

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Stars and Sickles - An Alternative Cold War

- Thread starter Hrvatskiwi

- Start date

-

- Tags

- cold war

Threadmarks

View all 121 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 97: The Crowned Crane Bows - Uganda (Until 1980) (Part 1) Chapter 98: The Conqueror? - Uganda (Until 1980) (Part 2) Chapter 99: Slaying the Beast - Uganda (Until 1980) (Part 3) Chapter 100 [SPECIAL] - Ad Astra - Aerospace Competition Between the Superpowers (Until 1980) (Part 1) Chapter 101 [SPECIAL] - Magnificent Desolation - Aerospace Competition Between the Superpowers (Until 1980) (Part 2) Chapter 102: Jadi Pandu Ibuku - Nusantara (Until 1980) Chapter 103: Furtive Seas - South Maluku and West Papua (Until 1980) Chapter 104: Kings and Kingmakers - Post-Independence North Kalimantan (Until 1980)Very true but cultural memory is a funny thing and sometimes certain works really take off in the imaginations of other countries.Alexander Bogdanov is a figure of the 20s - although he is actively remembered by the English-speaking ah-community, he is not so widely known in Russia. If we are talking about the post-war period, then the most outstanding and influential were Ivan Efremov and the Strugatsky Brothers. In those years (as now), among the pre-war ones, Alexander Belyaev and Alexei Tolstoy (in connection with Aelita) were most remembered.

Well Lumumba was assassinated IOTL. There wasnt an ABAKO revolt but Kasa-Vubu (who became president IOTL instead of Bolikango), used his presidential powers to oust Lumumba and several of his supporters from power. Mobutu used this opportunity to seize control of the military and murdered Lumumba, then dissolved his body in acid so that his grave couldnt be honoured. IOTL Dag Hammarskjold was UN secretary general and he was very hesitant to actually intervene in the secessions (although eventually they did against Katanga). ITTL, a more active and involved UN (as a holdover from having administered the territory directly), and no Kasa-Vubu presidency allows Lumumba to prevail.I absolutely loved this latest chapter

Can anyone tell me how this situation is different from otl events? What exactly happened for Lulumba to win the power struggle?

Basically I am asking this because I don't know otl events well and so can't compare them well. @Hrvatskiwi can you tell me in brief what went differently from otl. Like what was the biggest difference which caused events to go Lulumba's way?

I really enjoy his Martian novels, but there are definitely some funny parts about them. But also some interestingly forward-thinking content too, like some musings ok environmental destruction.His Martian novels were published in 1908-1912. Lenin used to joke about them.

Edit: good to see you here @WotanArgead

Also welcome @Cudymcar

Last edited:

Right - sorry. I don’t know why I wrote it like that.His Martian novels were published in 1908-1912. Lenin used to joke about them.

Glad to see that the Congo is not only doing well but also actively funding anti Apartheid forces and helping the MPLA, even if they aren't full on communists, I really hope they'll be able to eventually liberate Southern Africa from minority rule.

With the removal of Uranium from Katanga to Rhodesia would we see Rhodesia and South Africa start to work on nuclear weapons?

Wonder if this could not end up with Congo developing their own nukes in responseWith the removal of Uranium from Katanga to Rhodesia would we see Rhodesia and South Africa start to work on nuclear weapons?

We absolutely could see that happening. South Africa did have its own nuclear weapons programme IOTL.With the removal of Uranium from Katanga to Rhodesia would we see Rhodesia and South Africa start to work on nuclear weapons?

I mean... its only the logical response.Wonder if this could not end up with Congo developing their own nukes in response

I know this is kind of weird, but here lets see 3 characters and what their life is by the 1970s. In the 'Stars and sickles' timeline

1)

Abel Abraha. By late 1970s, this man is extremely unhappy that the damn Somalians defeated his great country in war. He is dejected and broken that despite passing on vital info, Siad Barre's troops were least affected by it and his nation has lost a huge chunk of its land forever. He has now retired and works in an Addis Ababa newspaper.

2)

Kamal Al-Jumblat. In the 1950s and 60s, this man worked as an agent for Gamal Abdel Nasser. He passed on vital inputs to Anti-British movements and the Egyptians. Despite his liberal stance he cooperated with Arab Nationalism. In the mid 60s he supported FLOSY but was unhappy when they were defeated and radical Marxists of the NLF took over instead. Even worse, the new government put him in jail because of his liberal writings (which causes them to suspect that he is a western agent). Thus by the late 70s, he rots in jail.

3)

Ico Ochoa. He was eventually proven right! Portugal did fall in not 10, but just 4 more years. Being in the MPLA, he got some good positions in the city administration of Luanada but after Nito Alves's coup, everything changed. The council communist Ochoa was charged with treason and revisionism and sent to labour camp in the forest where he remains to this day!

Hey @The Banker I'm glad you're enjoying this timeline and all but I'd prefer if you didn't post stuff from your Cold War Generator on here? I don't want to generate any potential confusion about the content of my timeline.

For instance someone reading your post there (since you literally said "in the Stars and Sickles timeline") could believe that these are characters in the timeline, or that details I havent mentioned (such as forest labour camps in Angola) are canon.

Also if you want to promote interest in your Cold War generator you could always do so in your own thread?

Last edited:

Chapter 95: There Isn't a Place Where Peace Reigns at Night - Rwanda and Burundi (Until 1980) (Part 1)

The small but densely populated nations of Rwanda and Burundi have long been intertwined in their history. A long and murky precolonial history was defined by the relationship between the Hutu and Tutsi peoples. The Twa People (in the past referred to as pygmies) were also present; a small ethnic group believed to have inhabited the region far longer than the Hutu and Tutsis. All three of these peoples speak Bantu languages, but seem to have represented waves of migration into the region over the centuries. Prior to the arrival of European colonists, the peoples of Rwanda-Burundi were organised under native kingdoms, where the agrarian Hutu were largely beneath the pastoralist Tutsis. Whilst some Hutus were able to achieve high office by merit, and certain particular sub-groups of Tutsi were very low in the social hierarchy, generally the caste system in Rwanda-Burundi favoured the Tutsis over the Hutu. The arrival of European colonisers, rather than upending this social hierarchy, actually ossified it. The Germans, who annexed the region into their colony of German East Africa, allowed the Rwandan and Burundian monarchies to maintain their authority, albeit at the cost of their sovereignty. The transfer of control over the colony from Berlin to Brussels saw a significant change in the relationship between the European rulers and their colonial subjects. The Belgians were far more involved in the territory than the Germans; the road network was significantly extended, as was the cultivation of cash crops, predominantly coffee and cotton in the rich volcanic soils of the region. This policy of course radically increased the profitability of the territory, but at a significant human cost; four famines ravaged the native population between 1916 and 1944 due to failures of the smaller food crops. Without being compelled to produce the more valuable commodities, it is likely that these famines could have been avoided. The Belgians also bureaucratised the ethnic caste system; formalising the hierarchy of tribal chiefs and sub-chiefs under the two Mwami (kings) in a manner that heavily favoured Tutsis. This hierarchy was based on the pseudoscientific "Hamitic hypothesis", which claimed that the Tutsis were of East African origin and were racially superior to the Hutus, a holdover of the "racial science" of the nineteenth century constructed to favour colonialism and white supremacy. By utilising the Tutsis as intermediaries, the Belgians ensured that most of the Hutu anger at their exploitation was directed at the Tutsi elite, rather than the European colonialists. Identity cards were handed out to subjects which specified their ethnicity (Hutu/Tutsi/Twa). In doing so, the Belgians eliminated the ability to shift between the different castes for their local subjects, something that did occur in the pre-colonial and German colonial periods from time to time. Another major impact the Belgians had was the proselytisation of Catholicism. Protestant missions were also allowed to operate but their influence was limited by a lack of subsidies; whereas the Catholic missions were funded by the government. An elite Catholic secondary school was established in Rwanda, but by the time of independence, there were barely 100 Africans educated beyond the secondary level in Rwanda and Burundi. The dissolution of Belgium and the transfer of Ruanda-Urundi from a UN Trust Territory under Belgian governance to a direct UN administration was largely a formality; the same governing structures remained intact. Unlike in Congo, the UN didn't set a date for independence. The more anachronistic governing structures in Ruanda-Urundi was believed to necessitate a longer presence than in Congo.

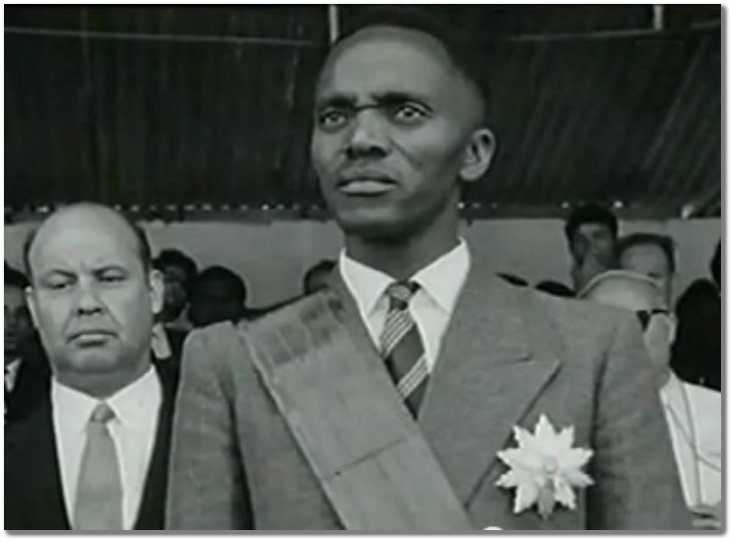

Mwami Mutara III Rudahigwa, the six foot-nine monarch of Rwanda

Nevertheless the growth of anti-colonial settlement in the Congo strongly influenced politics in Ruanda-Urundi. A cash economy had been developed since the end of the war, largely to facilitate movement of Rwandan and Burundian labour to the mines of Katanga province and the sugar plantations of Uganda. There was also a shift in the attitude of the local Catholic church authorities; an old, conservative Walloon generation was largely replaced with a younger Flemish clergy which saw in the Hutus' plights parallels with their own position relative to Walloons prior to Belgium's dissolution. A small group of Hutu notables had been educated by the Catholic Church and sought to push against Tutsi political control. The Church, which had once supported the pre-existing Tutsi hegemony, had now turned against it. Tension between the Hutu and Tutsi peoples began to intensify in the mid-1950s. July 1956 saw the publication in Congolese newspaper La Presse Africaine supposedly written by an anonymous Rwandan priest detailing historic wrongdoings by the Tutsi elite against the Hutu. This was followed up with many other articles about interethnic relations and history in Rwanda and Burundi. In Rwanda, King Mutara III Rudahigwa and the Tutsi elite denied a history of abuse and inequality. In September, a parliamentary election was held, with universal male suffrage. The population were permitted to vote for sub-chiefs, of whom 66% of those elected were Hutu. Higher positions, however, were still appointed and all of these positions were filled by the Tutsi. The results of these elections concerned the Tutsi elite, who feared that their power was slipping. King Mutara and his supporters began to agitate for immediate independence, hoping to solidify their political position. Seeing this, the Hutu counter-elite started to prepare to challenge the Tutsi elite head-on. Notable figures in this Hutu counter-elite were Grégoire Kayibanda and Joseph Gitera. Kayibanda had been active as an editor in at least two Catholic magazines (L'Ami and Kinyamateka) and had also been a board member for the TRAFIPRO food cooperative. Kayibanda founded the Mouvement Social Muhutu (Social Movement for Hutu People, MSM) political party. Gitera was more of a firebrand than Kayibanda. Gitera called for the abolition of the monarchy as early as 1957, but his rhetoric focused on class concerns over ethnic conflict. Gitera founded the Association Pour la Promotion Sociale de la Masse (Association for Social Promotion of the Masses, APROSOMA).

In 1958, Gitera visited King Mutara III at his palace at Nyanza. Mutara III treated Gitera with contempt, seeing him as an unruly subject acting above his station. The king even went so far as to throttle Gitera, and called him and his APROSOMA followers "inyangarwanda" ("haters of Rwanda"). Whilst some in the Hutu counter-elite had maintained hope that the monarchy could be used as a symbol of national unification in a future, equitable Rwanda, the king's abuse of Gitera shattered any such hopes. MSM, APROSOMA and Catholic publications took a harsher stance against monarchical power. The exposure of Mutara III's behaviour caused a rift between the king and the UN authorities, but attempts by the UN to limit his power were met with large demonstrations by Tutsis and regional chiefs (both Hutu and Tutsi). Early 1959 saw the UN establish a commission tasked with preparing Rwanda for independence. Elections were scheduled for the end of that year. Gitera began a campaign seeking the destruction of the kalinga, the royal drum which was a key symbol of monarchical power (akin to the crown jewels for the Queen of England). A paranoid Mutara III fled with the drum to Burundi, where he would die from a brain hemorrhage brought on by alcohol abuse. Persistent rumours that the king was murdered by the French or the Catholic Church further inflamed tensions back in Rwanda. Mutara III's brother was installed by the Tutsi elite, without input from the United Nations authority, as King Kigeli V Ndahindurwa. After Kigeli V's coronation, the Union Nationale Rwandaise (Rwandan National Union, UNAR) party was established under the leadership of François Rukeba. UNAR was a pro-monarchy party, but was not controlled by the king. Instead it was founded by François Rukeba, a Hutu (but of mixed parentage). UNAR was an ethnically-mixed party, but was predominantly Tutsi and aligned itself more with the Tutsi and traditional elites than with the Hutu counter-elite. UNAR promoted a policy of Africanisation, replacing European history with Rwandan history in the education programme, and seeking to limit the power of the Catholic Church and French influence in the economic activity of the kingdom. Gitera falsely claimed that the Catholic Church's anti-UNAR stance represented support for his party, and Kayibanda had the MSM rebranded as the Parti du Mouvement de l'Emancipation Hutu (Party of the Movement for the Emancipation of the Hutu, PARMEHUTU).

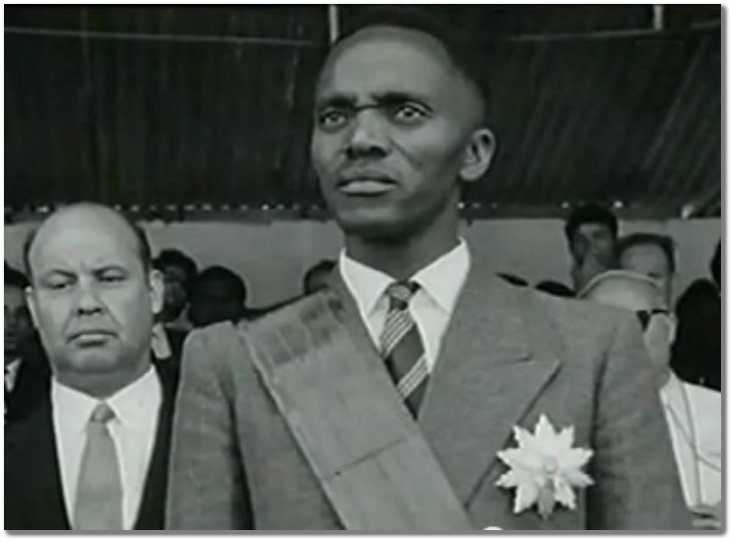

Grégoire Kayibanda, founder of PARMEHUTU

As inter-ethnic rivalry began to heat up, the UN administration attempted to prevent nationwide violence from breaking out. A trio of Tutsi chiefs was arrested by the UN authorities who were calling for violence against PARMEHUTU leaders. The UNAR submitted a protest letter to the UN Trust Territory authority, signed by many sub-chiefs. On 1st Novermber 1959, Dominique Mbonyumutwa, one of the few Hutu subchiefs and a known supporter of PARMEHUTU, was attacked by a gang of Tutsi youths, motivated by his refusal to sign the protest letter. Mbonyumutwa managed to escape with his wife without being seriously harmed, but a rumour swept the nation that Mbonyumutwa was killed. The latter's failure to appear publicly in the aftermath of the attack suggests that he was willing to take advantage of the situation to politically mobilise Hutus. The next two days saw a Hutu protest in Ndiza outside the home of Athanase Gashagaza, a Tutsi chief who was Mbonyumutwa's direct superior in the traditional aristocratic hierarchy. On the second day, violence sparked. Hutu vigilantes, yelling the slogan "for God, the Church, and Rwanda" killed two Tutsi officials and drove Gashagaza into hiding. A Hutu, Mbonyumutwa, was named as Gashagaza's replacement in the hopes of preventing violence. But the spark had already been struck. A wave of arson attacks throughout the country targeting Tutsi dwellings spread throughout the country, and protests turned to riots. The pitiful UN garrison, which was really just a rebranded Belgian colonial force, numbered only 300, and couldn't ensure the safety of Tutsis. A large-scale migration of Tutsis into Congo, Uganda and Tanganyika commenced whilst reinforcements were sent from the UN garrison in Congo. Kigeli V requested permission from the Trust authority to mobilise his own armed force to maintain law and order, but this was refused, as the UN administrators assumed it would lead to civil war. Ignoring the refusal, Kigeli V mobilised a militia (although "mob" might be a more accurate descriptor). On 7th November, Kigeli put his army on the move, and ordered the arrest and killing of a number of prominent Hutu leaders. Gitera's brother was among those killed. Many of the PARMEHUTU leaders who were arrested would be tortured by UNAR officials at the royal palace. Kayibanda had gone into hiding, and could not be found by the royal militia, so they focused instead on the capture of Gitera. An APROSOMA-led militia was quickly scrabbled together, which took a stand at a hill near Save, at the approaches to Gitera's home town of Astrida. The royal militia didn't attempt to storm the APROSOMA position at the top of the hill, lacking the military expertise to attack a prepared enemy on high ground. UN forces arrived on 10th November, preventing bloodshed and allowing Gitera's escape. Whilst UNAR remained more powerful than the Hutu parties, they now saw the UN as no different to the colonial authorities, and believed (falsely) that they had thrown their lot in with the Hutu side[222]. The UN also forced the King to release captured PARMEHUTU leaders or face deposition. PARMEHUTU got a major boost from the Tutsi coup. APROSOMA's ethnically-inclusive policy became much less popular after the violent attempts to suppress opposition by the Tutsi elite, regardless of what had actually sparked the situation. PARMEHUTU leaders, believing that the longer the UN was present in Rwanda, the better they could consolidate their influence, lobbied the Trust authorities to postpone elections scheduled for January 1960 to July. In March a high-level UN delegation arrived in Rwanda. Wanting to give the image of having widespread popular support, all three major parties held demonstrations. This devolved into violence however and the sight of Tutsis homes on fire left a lasting impression on the UN delegation. The United Nations declared the election plans unworkable and cancelled them, instead organising a round-table discussion with representatives from APROSOMA, PARMEHUTU, and UNAR [223]. The Nyanza Conference, held in April, was largely unsuccessful. PARMEHUTU and UNAR in particular were unwilling to work with each other or to share power in a national unity government. The UN representatives argued that if necessary, APROSOMA would be installed in order to maintain ethnic parity. PARMEHUTU and UNAR officials argued that an APROSOMA government would be unpopular and have no mandate. The insurmountability of the different parties' interests forced the UN to set a date for elections in January 1961. They also stated that they would be free elections with UN forces at voting stations to prevent electoral violence or vote-rigging. All parties agreed: APROSOMA believed they could successfully campaign on the promise of peace; PARMEHUTU considered their win a foregone conclusion, and UNAR believed that the Tutsi sub-chiefs could pressure their subjects effectively enough to become the ruling party.

Neighbouring Burundi was also inhabited by Hutu, Tutsi and Great Lakes Twa people, but their monarchy was less committed to ethnic rivalry than in Rwanda. Whilst Burundi also had a disproportionately Tutsi aristocracy, the king and his closest councillors were of the Ganwa people; a distinct social group that regardless of its (uncertain) ancestral origins, was perceived as an ethnic group apart from the Hutu, Tutsi or Twa. This "royal line" was dominated by two clans which often competed for control over the state; the Bezi and the Tare. The most important politician of the independence period in Burundi was Louis Rwagasore. Rwagasore was a son of Mwami Mwambutsa IV, King of Burundi. Rwagasore saw the dissolution of Belgium and the transfer of Burundi to United Nations authority as presenting an opportunity for native control over commercial activity in the kingdom. In June 1957 Rwagasore founded a federation of cooperatives, the Coopératives des Commerçants du Burundi (Traders' Cooperatives of Burundi, CCB) in order to empower native commerce. Whilst the remnants of Belgian colonial interests, now under France's control, opposed the CCB, it proved extremely popular with the Swahili traders of the capital Usumbura. In its first public meeting, the CCB drew a crowd of 200 merchants and managed to secure several favourable contracts with exporters. The CCB would eventually run into financial trouble, the causes of which are uncertain in the historical record. Opponents of Rwagasore claimed that he was embezzling significant sums from the CCB, whilst his supporters claim that French commercial interests were operating to clandestinely undermine the CCB. In any case, the financial trouble necessitated an international campaign seeking investment. This campaign was unsuccessful, although it did allow him to forge a good personal relationship with Julius Nyerere in Tanganyika. Rwagasore would end up acquiring credit for the CCB from the Supreme Land Council, an advisory body with royal oversight which had some influence on the national budget.

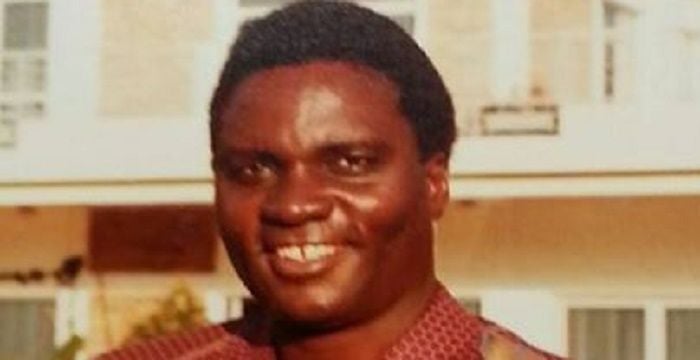

Louis Rwagasore, Prince of Burundi, head of UPRONA and Burundi's first Prime Minister

Shortly after the CCB fiasco, Rwagasore became involved with the nascent Union pour le Progrès national (Union for National Progress, UPRONA) political party. UPRONA was quickly able to secure the early financial support of the Swahili population in Bujumbura, particularly the traders. Rwagasore had sought replication of the concerning inter-ethnic situation in neighbouring Rwanda; rallying Tutsis and Hutus alike to his cause. Nevertheless, UPRONA couldn't avoid being drawn into the competition between the Ganwa clans. The French mercantile interests in Burundi had encouraged the creation of the Parti Démocratique Chrétien (Christian Democratic Party, PDC) affiliated with the Tare clan in order to counteract Rwagasore's appeals to economic nationalism. The PDC was founded by Jean-Baptiste Ntidendereza, whose brother Joseph Biroli would be party president. Both were Tare. The Bezi, of which Rwagasore was a member, were closely associated with UPRONA. Rwagasore also fell out with his father, Mwambutsa IV, with whom he was never particularly close. The Mwami had encouraged prospective political opposition to Rwagasore, as to ensure that his power remained unchallenged. Having benefitted from relationships with the Belgian/French colonial interests in Burundi, Mwambutsa also disliked the manner with which Rwagasore targeted colonialism in his appeals to the Burundian masses. Rwagasore's political programme promised modernisation, and sought to establish a constitutional monarchy. UPRONA sought to be a broad-based coalition that would rule through consensus, and would be non-aligned in the international competition between the Soviet and US-led blocs. Trying to ensure that Burundi wouldn't encounter the pitfalls of the ethnic party system in Rwanda, both Hutus and Tutsis were put into high-level positions in UPRONA, which was intentionally structured to split important positions equitably between the two major ethnic groups. Despite Rwagasore's best efforts, UPRONA hadn't truly cultivated a mass political base. This may have actually helped it maintain its cohesion, however, as a mass political movement would likely skew towards Hutu interests, considering the country's demography. Rwagasore's populist tendencies and dominance of the party did lead many of the chiefs who had initially formed UPRONA to leave, including founding member Léopold Biha, a close confidany of King Mwambutsa IV.

PDC functionaries began a smear campaign against Rwagasore. They claimed (because of rumours that Mwambutsa IV had decided that Rwagasore's younger brother Charles would succeed him instead of the elder brother Rwagasore) that UPRONA was merely a vehicle Rwagasore intended to use to become king; Rwagasore responded with a promise that, king or not, he would fight for the people of Burundi. In 1959, Tare leader Pierre Baranyanka questioned whether Mwambutsa's marriage to Rwagasore's mother Kanyonga was legitimate according to Burundian custom; implying that he was a bastard with no claim to the throne. Antipathy grew, especially as UPRONA made inroads into Baranyanka's district of Ndora-Kayanza, which the Belgians had appointed him chief of in 1929. Baranyanka, enraged, threatened to have Rwagasore's in-laws living in nearby Rukecu raped by Twas. As the political competition between Baranyanka and Rwagasore grew, the latter began to carry a gun on him at all times, fearing assassination. Some hope remained for a peaceful transition to independence, however. On July 15th 1960, as neighbouring Congo began to descend into the chaos of its immediate post-independence, Rwagasore released a joint communique with Joseph Biroli appealing for calm, and stating that Burundi had "the unique chance... to create in the heart of Africa an island of peace, tranquility and prosperity". As parties made preparations for the 1961 legislative elections, the PDC allied with other parties to create an anti-UPRONA coalition, the Front Commun (Common Front, FC). UPRONA won the elections, which had 80% turnout, with 58 of 64 seats in the legislative assembly won by Rwagasore's party. Angered by their loss, PFC supporters in Mukenke, Kirundo Province, rioted and attacked UPRONA members. Rwagasore appealed to his supporters not to be provoked by this violence, and the UN authorities quickly restored order. With a clear mandate as formateur, Rwagasore brought the defeated parties into government. Pierre Ngendandumwe, a well-educated Hutu from the PDC, was named deputy prime minister. Rwagasore's brother-in-law, André Muhirwa, became Minister of the Interior, significantly decreasing the likelihood of a coup. Despite the strong democratic mandate of Rwagasore's national unity government, the Tare were still angered, perceiving Rwagasore's victory as a Bezi takeover, even though the formateur sought to appease them by appointing a Tare as Director of Tourism.

===

[222] IOTL, this was kinda the case. The UN Trust Territory under Belgian administration essentially lead to multiple layers of power in Rwanda and Burundi: Hutu / Tutsi / Belgian / UN (ascending order); but in effect the UN had very little influence over the mechanisms of power. ITTL, with the dissolution of the Belgian state, you have an administrative apparatus largely staffed by Belgians (now French and Dutchmen officially) but where they are overseen by UN superiors. This helps keep things from being too set up to "screw" non-compliant leadership. IOTL the Belgians had decided to side with the Hutus. Many of them, in the church and without, saw this as a good thing, toppling an unfair aristocracy. Others simply saw resurgent monarchical and Tutsi power as a threat to their economic interests. They really opened Pandora's Box though. ITTL however without the direct Belgian administration you don't get figures like Guy Logiest, who stacked things in the Hutus' favour in preparation for independence.

[223] IOTL, the Belgians ignored the UN's recommendations to postpone elections and instead pressed ahead with them.

Mwami Mutara III Rudahigwa, the six foot-nine monarch of Rwanda

Nevertheless the growth of anti-colonial settlement in the Congo strongly influenced politics in Ruanda-Urundi. A cash economy had been developed since the end of the war, largely to facilitate movement of Rwandan and Burundian labour to the mines of Katanga province and the sugar plantations of Uganda. There was also a shift in the attitude of the local Catholic church authorities; an old, conservative Walloon generation was largely replaced with a younger Flemish clergy which saw in the Hutus' plights parallels with their own position relative to Walloons prior to Belgium's dissolution. A small group of Hutu notables had been educated by the Catholic Church and sought to push against Tutsi political control. The Church, which had once supported the pre-existing Tutsi hegemony, had now turned against it. Tension between the Hutu and Tutsi peoples began to intensify in the mid-1950s. July 1956 saw the publication in Congolese newspaper La Presse Africaine supposedly written by an anonymous Rwandan priest detailing historic wrongdoings by the Tutsi elite against the Hutu. This was followed up with many other articles about interethnic relations and history in Rwanda and Burundi. In Rwanda, King Mutara III Rudahigwa and the Tutsi elite denied a history of abuse and inequality. In September, a parliamentary election was held, with universal male suffrage. The population were permitted to vote for sub-chiefs, of whom 66% of those elected were Hutu. Higher positions, however, were still appointed and all of these positions were filled by the Tutsi. The results of these elections concerned the Tutsi elite, who feared that their power was slipping. King Mutara and his supporters began to agitate for immediate independence, hoping to solidify their political position. Seeing this, the Hutu counter-elite started to prepare to challenge the Tutsi elite head-on. Notable figures in this Hutu counter-elite were Grégoire Kayibanda and Joseph Gitera. Kayibanda had been active as an editor in at least two Catholic magazines (L'Ami and Kinyamateka) and had also been a board member for the TRAFIPRO food cooperative. Kayibanda founded the Mouvement Social Muhutu (Social Movement for Hutu People, MSM) political party. Gitera was more of a firebrand than Kayibanda. Gitera called for the abolition of the monarchy as early as 1957, but his rhetoric focused on class concerns over ethnic conflict. Gitera founded the Association Pour la Promotion Sociale de la Masse (Association for Social Promotion of the Masses, APROSOMA).

In 1958, Gitera visited King Mutara III at his palace at Nyanza. Mutara III treated Gitera with contempt, seeing him as an unruly subject acting above his station. The king even went so far as to throttle Gitera, and called him and his APROSOMA followers "inyangarwanda" ("haters of Rwanda"). Whilst some in the Hutu counter-elite had maintained hope that the monarchy could be used as a symbol of national unification in a future, equitable Rwanda, the king's abuse of Gitera shattered any such hopes. MSM, APROSOMA and Catholic publications took a harsher stance against monarchical power. The exposure of Mutara III's behaviour caused a rift between the king and the UN authorities, but attempts by the UN to limit his power were met with large demonstrations by Tutsis and regional chiefs (both Hutu and Tutsi). Early 1959 saw the UN establish a commission tasked with preparing Rwanda for independence. Elections were scheduled for the end of that year. Gitera began a campaign seeking the destruction of the kalinga, the royal drum which was a key symbol of monarchical power (akin to the crown jewels for the Queen of England). A paranoid Mutara III fled with the drum to Burundi, where he would die from a brain hemorrhage brought on by alcohol abuse. Persistent rumours that the king was murdered by the French or the Catholic Church further inflamed tensions back in Rwanda. Mutara III's brother was installed by the Tutsi elite, without input from the United Nations authority, as King Kigeli V Ndahindurwa. After Kigeli V's coronation, the Union Nationale Rwandaise (Rwandan National Union, UNAR) party was established under the leadership of François Rukeba. UNAR was a pro-monarchy party, but was not controlled by the king. Instead it was founded by François Rukeba, a Hutu (but of mixed parentage). UNAR was an ethnically-mixed party, but was predominantly Tutsi and aligned itself more with the Tutsi and traditional elites than with the Hutu counter-elite. UNAR promoted a policy of Africanisation, replacing European history with Rwandan history in the education programme, and seeking to limit the power of the Catholic Church and French influence in the economic activity of the kingdom. Gitera falsely claimed that the Catholic Church's anti-UNAR stance represented support for his party, and Kayibanda had the MSM rebranded as the Parti du Mouvement de l'Emancipation Hutu (Party of the Movement for the Emancipation of the Hutu, PARMEHUTU).

Grégoire Kayibanda, founder of PARMEHUTU

As inter-ethnic rivalry began to heat up, the UN administration attempted to prevent nationwide violence from breaking out. A trio of Tutsi chiefs was arrested by the UN authorities who were calling for violence against PARMEHUTU leaders. The UNAR submitted a protest letter to the UN Trust Territory authority, signed by many sub-chiefs. On 1st Novermber 1959, Dominique Mbonyumutwa, one of the few Hutu subchiefs and a known supporter of PARMEHUTU, was attacked by a gang of Tutsi youths, motivated by his refusal to sign the protest letter. Mbonyumutwa managed to escape with his wife without being seriously harmed, but a rumour swept the nation that Mbonyumutwa was killed. The latter's failure to appear publicly in the aftermath of the attack suggests that he was willing to take advantage of the situation to politically mobilise Hutus. The next two days saw a Hutu protest in Ndiza outside the home of Athanase Gashagaza, a Tutsi chief who was Mbonyumutwa's direct superior in the traditional aristocratic hierarchy. On the second day, violence sparked. Hutu vigilantes, yelling the slogan "for God, the Church, and Rwanda" killed two Tutsi officials and drove Gashagaza into hiding. A Hutu, Mbonyumutwa, was named as Gashagaza's replacement in the hopes of preventing violence. But the spark had already been struck. A wave of arson attacks throughout the country targeting Tutsi dwellings spread throughout the country, and protests turned to riots. The pitiful UN garrison, which was really just a rebranded Belgian colonial force, numbered only 300, and couldn't ensure the safety of Tutsis. A large-scale migration of Tutsis into Congo, Uganda and Tanganyika commenced whilst reinforcements were sent from the UN garrison in Congo. Kigeli V requested permission from the Trust authority to mobilise his own armed force to maintain law and order, but this was refused, as the UN administrators assumed it would lead to civil war. Ignoring the refusal, Kigeli V mobilised a militia (although "mob" might be a more accurate descriptor). On 7th November, Kigeli put his army on the move, and ordered the arrest and killing of a number of prominent Hutu leaders. Gitera's brother was among those killed. Many of the PARMEHUTU leaders who were arrested would be tortured by UNAR officials at the royal palace. Kayibanda had gone into hiding, and could not be found by the royal militia, so they focused instead on the capture of Gitera. An APROSOMA-led militia was quickly scrabbled together, which took a stand at a hill near Save, at the approaches to Gitera's home town of Astrida. The royal militia didn't attempt to storm the APROSOMA position at the top of the hill, lacking the military expertise to attack a prepared enemy on high ground. UN forces arrived on 10th November, preventing bloodshed and allowing Gitera's escape. Whilst UNAR remained more powerful than the Hutu parties, they now saw the UN as no different to the colonial authorities, and believed (falsely) that they had thrown their lot in with the Hutu side[222]. The UN also forced the King to release captured PARMEHUTU leaders or face deposition. PARMEHUTU got a major boost from the Tutsi coup. APROSOMA's ethnically-inclusive policy became much less popular after the violent attempts to suppress opposition by the Tutsi elite, regardless of what had actually sparked the situation. PARMEHUTU leaders, believing that the longer the UN was present in Rwanda, the better they could consolidate their influence, lobbied the Trust authorities to postpone elections scheduled for January 1960 to July. In March a high-level UN delegation arrived in Rwanda. Wanting to give the image of having widespread popular support, all three major parties held demonstrations. This devolved into violence however and the sight of Tutsis homes on fire left a lasting impression on the UN delegation. The United Nations declared the election plans unworkable and cancelled them, instead organising a round-table discussion with representatives from APROSOMA, PARMEHUTU, and UNAR [223]. The Nyanza Conference, held in April, was largely unsuccessful. PARMEHUTU and UNAR in particular were unwilling to work with each other or to share power in a national unity government. The UN representatives argued that if necessary, APROSOMA would be installed in order to maintain ethnic parity. PARMEHUTU and UNAR officials argued that an APROSOMA government would be unpopular and have no mandate. The insurmountability of the different parties' interests forced the UN to set a date for elections in January 1961. They also stated that they would be free elections with UN forces at voting stations to prevent electoral violence or vote-rigging. All parties agreed: APROSOMA believed they could successfully campaign on the promise of peace; PARMEHUTU considered their win a foregone conclusion, and UNAR believed that the Tutsi sub-chiefs could pressure their subjects effectively enough to become the ruling party.

Neighbouring Burundi was also inhabited by Hutu, Tutsi and Great Lakes Twa people, but their monarchy was less committed to ethnic rivalry than in Rwanda. Whilst Burundi also had a disproportionately Tutsi aristocracy, the king and his closest councillors were of the Ganwa people; a distinct social group that regardless of its (uncertain) ancestral origins, was perceived as an ethnic group apart from the Hutu, Tutsi or Twa. This "royal line" was dominated by two clans which often competed for control over the state; the Bezi and the Tare. The most important politician of the independence period in Burundi was Louis Rwagasore. Rwagasore was a son of Mwami Mwambutsa IV, King of Burundi. Rwagasore saw the dissolution of Belgium and the transfer of Burundi to United Nations authority as presenting an opportunity for native control over commercial activity in the kingdom. In June 1957 Rwagasore founded a federation of cooperatives, the Coopératives des Commerçants du Burundi (Traders' Cooperatives of Burundi, CCB) in order to empower native commerce. Whilst the remnants of Belgian colonial interests, now under France's control, opposed the CCB, it proved extremely popular with the Swahili traders of the capital Usumbura. In its first public meeting, the CCB drew a crowd of 200 merchants and managed to secure several favourable contracts with exporters. The CCB would eventually run into financial trouble, the causes of which are uncertain in the historical record. Opponents of Rwagasore claimed that he was embezzling significant sums from the CCB, whilst his supporters claim that French commercial interests were operating to clandestinely undermine the CCB. In any case, the financial trouble necessitated an international campaign seeking investment. This campaign was unsuccessful, although it did allow him to forge a good personal relationship with Julius Nyerere in Tanganyika. Rwagasore would end up acquiring credit for the CCB from the Supreme Land Council, an advisory body with royal oversight which had some influence on the national budget.

Louis Rwagasore, Prince of Burundi, head of UPRONA and Burundi's first Prime Minister

Shortly after the CCB fiasco, Rwagasore became involved with the nascent Union pour le Progrès national (Union for National Progress, UPRONA) political party. UPRONA was quickly able to secure the early financial support of the Swahili population in Bujumbura, particularly the traders. Rwagasore had sought replication of the concerning inter-ethnic situation in neighbouring Rwanda; rallying Tutsis and Hutus alike to his cause. Nevertheless, UPRONA couldn't avoid being drawn into the competition between the Ganwa clans. The French mercantile interests in Burundi had encouraged the creation of the Parti Démocratique Chrétien (Christian Democratic Party, PDC) affiliated with the Tare clan in order to counteract Rwagasore's appeals to economic nationalism. The PDC was founded by Jean-Baptiste Ntidendereza, whose brother Joseph Biroli would be party president. Both were Tare. The Bezi, of which Rwagasore was a member, were closely associated with UPRONA. Rwagasore also fell out with his father, Mwambutsa IV, with whom he was never particularly close. The Mwami had encouraged prospective political opposition to Rwagasore, as to ensure that his power remained unchallenged. Having benefitted from relationships with the Belgian/French colonial interests in Burundi, Mwambutsa also disliked the manner with which Rwagasore targeted colonialism in his appeals to the Burundian masses. Rwagasore's political programme promised modernisation, and sought to establish a constitutional monarchy. UPRONA sought to be a broad-based coalition that would rule through consensus, and would be non-aligned in the international competition between the Soviet and US-led blocs. Trying to ensure that Burundi wouldn't encounter the pitfalls of the ethnic party system in Rwanda, both Hutus and Tutsis were put into high-level positions in UPRONA, which was intentionally structured to split important positions equitably between the two major ethnic groups. Despite Rwagasore's best efforts, UPRONA hadn't truly cultivated a mass political base. This may have actually helped it maintain its cohesion, however, as a mass political movement would likely skew towards Hutu interests, considering the country's demography. Rwagasore's populist tendencies and dominance of the party did lead many of the chiefs who had initially formed UPRONA to leave, including founding member Léopold Biha, a close confidany of King Mwambutsa IV.

PDC functionaries began a smear campaign against Rwagasore. They claimed (because of rumours that Mwambutsa IV had decided that Rwagasore's younger brother Charles would succeed him instead of the elder brother Rwagasore) that UPRONA was merely a vehicle Rwagasore intended to use to become king; Rwagasore responded with a promise that, king or not, he would fight for the people of Burundi. In 1959, Tare leader Pierre Baranyanka questioned whether Mwambutsa's marriage to Rwagasore's mother Kanyonga was legitimate according to Burundian custom; implying that he was a bastard with no claim to the throne. Antipathy grew, especially as UPRONA made inroads into Baranyanka's district of Ndora-Kayanza, which the Belgians had appointed him chief of in 1929. Baranyanka, enraged, threatened to have Rwagasore's in-laws living in nearby Rukecu raped by Twas. As the political competition between Baranyanka and Rwagasore grew, the latter began to carry a gun on him at all times, fearing assassination. Some hope remained for a peaceful transition to independence, however. On July 15th 1960, as neighbouring Congo began to descend into the chaos of its immediate post-independence, Rwagasore released a joint communique with Joseph Biroli appealing for calm, and stating that Burundi had "the unique chance... to create in the heart of Africa an island of peace, tranquility and prosperity". As parties made preparations for the 1961 legislative elections, the PDC allied with other parties to create an anti-UPRONA coalition, the Front Commun (Common Front, FC). UPRONA won the elections, which had 80% turnout, with 58 of 64 seats in the legislative assembly won by Rwagasore's party. Angered by their loss, PFC supporters in Mukenke, Kirundo Province, rioted and attacked UPRONA members. Rwagasore appealed to his supporters not to be provoked by this violence, and the UN authorities quickly restored order. With a clear mandate as formateur, Rwagasore brought the defeated parties into government. Pierre Ngendandumwe, a well-educated Hutu from the PDC, was named deputy prime minister. Rwagasore's brother-in-law, André Muhirwa, became Minister of the Interior, significantly decreasing the likelihood of a coup. Despite the strong democratic mandate of Rwagasore's national unity government, the Tare were still angered, perceiving Rwagasore's victory as a Bezi takeover, even though the formateur sought to appease them by appointing a Tare as Director of Tourism.

===

[222] IOTL, this was kinda the case. The UN Trust Territory under Belgian administration essentially lead to multiple layers of power in Rwanda and Burundi: Hutu / Tutsi / Belgian / UN (ascending order); but in effect the UN had very little influence over the mechanisms of power. ITTL, with the dissolution of the Belgian state, you have an administrative apparatus largely staffed by Belgians (now French and Dutchmen officially) but where they are overseen by UN superiors. This helps keep things from being too set up to "screw" non-compliant leadership. IOTL the Belgians had decided to side with the Hutus. Many of them, in the church and without, saw this as a good thing, toppling an unfair aristocracy. Others simply saw resurgent monarchical and Tutsi power as a threat to their economic interests. They really opened Pandora's Box though. ITTL however without the direct Belgian administration you don't get figures like Guy Logiest, who stacked things in the Hutus' favour in preparation for independence.

[223] IOTL, the Belgians ignored the UN's recommendations to postpone elections and instead pressed ahead with them.

Last edited:

Things are looking tense but hopefully with a powerful Congo at their side, these countries can avoid the chaos that followed and especially avoid the genocide

Chapter 96: When There is Peace, Daggers are Used for Shaving - Rwanda and Burundi (Until 1980) (Part 2)

Burundi's post-independence stability relative to its Rwandan neighbour can largely be traced to Louis Rwagasore's ability to maintain an inclusive, broad-based government. Whilst there was still tension between elements of the Tare clan and Rwagasore's government, the assassination attempt that Rwagasore feared never came to pass [224]. To appease Tare opponents, he appointed several of them as ambassadors to various friendly nations, providing those individuals with a prestigous position in the new government (and the perks of international travel). Rwagasore maintained cordial, if somewhat distant relations with Lumumba's Congo, but his close personal friendship with Tanganyikan President Julius Nyerere faciliated ties not only with Dar es Salaam but with Peking as well. Chinese aid was instrumental in the economic modernisation of Burundi, which saw the construction of two hydroelectric dams [225], the expansion of infrastructure providing drinking water, and the construction of a port on Lake Tanganyika to encourage regional trade. The largely agrarian economy of Burundi also benefitted from Chinese provision of tractors and other agricultural equipment, allowing Burundi to increase production of coffee, tea and sugar. Economic integration between the Burundi-Rwanda economic union (which had been retained from the colonial and UN administration) and Tanganyika was encouraged as steps towards a confederal East African Union. Despite an increase in overall economic prosperity, anxieties about a potential spillover of conflict from Rwanda to Burundi haunted Burundian politics. Rwagasore could not step down from office due to internal divisions in the party between Paul Mirerekano, a Hutu and an old friend of Rwagasore's who had been an important composer of UPRONA's political programme (who had nevertheless not been a member of the first UPRONA government) and André Muhirwa. Rwagasore was still the arbiter of UPRONA's policy, but he would need to see more consensus between his party members before relinquishing his hold on power. Determined not to get directly involved in the events in Rwanda, Rwagasore refused entry of UNAR Tutsi rebels into Burundi in 1963, forcing them instead to operate out of bases in Uganda and Congo[226]. In 1977, Mwami Mwambutsa passed away[227]. Irritated by Rwagasore's move to reduce the monarchy's political influence through the adoption of a new constitution in 1964 which turned Burundi into a constitutional monarchy, Mwambutsa had named his younger son, Charles Ndizege, as monarch. Whilst some supporters of Rwagasore were irritated with this, claiming that Rwagasore was the rightful claimant, in the interests of political stability and separation of powers Rwagasore renounced his claim and congratulated his younger brother on his coronation. Ndizege took the regnal name Ntare V.

In Rwanda, the January 1961 elections resulted in a clear victory for PARMEHUTU. A referendum in July on the issue of whether or not to retain the monarchy gave the government an unambiguous mandate to abolish the monarchy. Kigeli V went into exile, moving between various East African cities. The first government of independent Rwanda was lead by Prime Minister Grégoire Kayibanda, who appointed Dominique Mbonyumutwa as President. The Kayibanda government promoted a policy of international non-alignment, focusing instead on the establishment of ties with various countries around the globe. Kayibanda's government did little to face issues of corruption and economic inefficiency, however. They also instituted a number of 'democratisation' measures that were used in order to dilute the influence of the Rwandan Tutsis. Quotas were established in secondary schools and the civil service which limited Tutsis to a mere 9% of spots, proportionate to their total population. Whilst it is understandable that Tutsis couldn't retain as large a role as they had in administration prior to independence, this pushed a number of experienced civil servants out of work, and exacerbated ethnic tensions due to high unemployment rates. Many of the now jobless Tutsis were unable to find alternative employment. Rather than emphasising a united Rwandan identity regardless of ethnicity, Kayibanda maintained the pre-independence ID system, which still specified ethnic affiliation.

PARMEHUTU policies continued to encourage Tutsi emigration from Rwanda. Some of these Tutsi were allowed into Burundi, although the Rwagasore government limited the influx in order to not upset too much the ethnic balance in their kingdom, and some also fled to Tanganyika, but the majority resettled in the border regions of Uganda and Congo (in the latter these Tutsi refugees were referred to as "Banyamalenge"). Burundi's refusal to let in UNAR rebels, along with Rwagasore's constant efforts to maintain good relations with Kayibanda, convinced the latter to retain the economic union with Burundi[228]. 1963 saw a major incursion by UNAR rebels that crossed the border from Congolese South Kivu into Rwanda. This attack was repelled by the Rwandan gendarmerie, but cross-border night raids from Congo continued to be a problem for Kayibanda and his government. The recruitment of not-insignificant numbers of Banyamalenge into the Congolese military, and the cross-border raids convinced Kayibanda that Lumumba was seeking to overthrow his government and put in place a pliant regime. In reality, Lumumba cared little for the going-ons on in Rwanda, focusing instead on competition with the Rhodesians and South Africans. The vast size of Congo simply allowed UNAR rebels to operate in remote areas of South Kivu without Congolese government support. The language used in anti-Tutsi rhetoric by PARMEHUTU officials became ever graver; the UNAR rebels who infiltrated at night were referred to as inyenzi ("cockroaches") due to their disappearance in the daylight. This dehumanising language was soon extended to the Tutsi population that still lived in Rwanda. The threat of the UNAR rebels to the Rwandan state was also exaggerated in the minds of the PARMEHUTU leadership and their supporters; rather than a multinational conspiracy, the raiding rebels were fractured and largely operated independently. Whilst their raids were a serious threat to the lives of civilians living in the border areas, as well as to security forces personnel, a Tutsi march on Kigali wasn't likely, at least without significant foreign support.

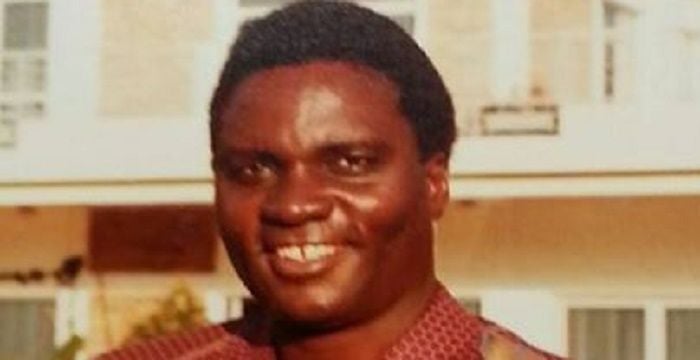

Juvénal Habyarimana

In July 1973, the Kayibanda government was toppled by a coup d'état headed by his defense minister, Major General Juvénal Habyarimana. Despite some initial overtures to the Tutsi population, Habyarimana soon reversed course to perpetuate the anti-Tutsi policies of his predecessor. In 1975, Habyarimana established his own political party, the Mouvement Révolutionnaire National pour le Développement (National Revolutionary Movement for Development, MRND) and outlawed all others. A 1978 constitution implemented by the MRND defined Rwanda as a presidential republic with no term limits. Habyarimana, the only name on the ballot, was also elected to a five-year term as President.

===

[224] IOTL Rwagasore was assassinated by a Greek national in the employ of the PDC. Details are uncertain, but it appears that the factor that pushed the PDC to go through with the assassination was encouragement by the Belgian resident. ITTL no Belgian resident, the PDC don't dare to kill Rwagasore without Western support.

[225] IOTL such economic modernisation wouldn't occur until the late 1970s and early 1980s under the purview of Jean-Baptiste Bagaza, a military dictator of Burundi.

[226] IOTL, the pro-Tutsi governments that came about in the aftermath of Rwagasore's assassination allowed these rebels to operate out of Burundi, which further inflamed ethnic tensions in Burundi itself.

[227] IOTL, a Hutu coup in 1965 toppled the Burundian monarchy, which went into exile and Mwambutsa himself ended up living out the rest of his life in Switzerland. ITTL, the monarchy isn't topped.

[228] IOTL this union was dissolved due to the post-Rwagasore Burundian government's harbouring of UNAR rebels.

In Rwanda, the January 1961 elections resulted in a clear victory for PARMEHUTU. A referendum in July on the issue of whether or not to retain the monarchy gave the government an unambiguous mandate to abolish the monarchy. Kigeli V went into exile, moving between various East African cities. The first government of independent Rwanda was lead by Prime Minister Grégoire Kayibanda, who appointed Dominique Mbonyumutwa as President. The Kayibanda government promoted a policy of international non-alignment, focusing instead on the establishment of ties with various countries around the globe. Kayibanda's government did little to face issues of corruption and economic inefficiency, however. They also instituted a number of 'democratisation' measures that were used in order to dilute the influence of the Rwandan Tutsis. Quotas were established in secondary schools and the civil service which limited Tutsis to a mere 9% of spots, proportionate to their total population. Whilst it is understandable that Tutsis couldn't retain as large a role as they had in administration prior to independence, this pushed a number of experienced civil servants out of work, and exacerbated ethnic tensions due to high unemployment rates. Many of the now jobless Tutsis were unable to find alternative employment. Rather than emphasising a united Rwandan identity regardless of ethnicity, Kayibanda maintained the pre-independence ID system, which still specified ethnic affiliation.

PARMEHUTU policies continued to encourage Tutsi emigration from Rwanda. Some of these Tutsi were allowed into Burundi, although the Rwagasore government limited the influx in order to not upset too much the ethnic balance in their kingdom, and some also fled to Tanganyika, but the majority resettled in the border regions of Uganda and Congo (in the latter these Tutsi refugees were referred to as "Banyamalenge"). Burundi's refusal to let in UNAR rebels, along with Rwagasore's constant efforts to maintain good relations with Kayibanda, convinced the latter to retain the economic union with Burundi[228]. 1963 saw a major incursion by UNAR rebels that crossed the border from Congolese South Kivu into Rwanda. This attack was repelled by the Rwandan gendarmerie, but cross-border night raids from Congo continued to be a problem for Kayibanda and his government. The recruitment of not-insignificant numbers of Banyamalenge into the Congolese military, and the cross-border raids convinced Kayibanda that Lumumba was seeking to overthrow his government and put in place a pliant regime. In reality, Lumumba cared little for the going-ons on in Rwanda, focusing instead on competition with the Rhodesians and South Africans. The vast size of Congo simply allowed UNAR rebels to operate in remote areas of South Kivu without Congolese government support. The language used in anti-Tutsi rhetoric by PARMEHUTU officials became ever graver; the UNAR rebels who infiltrated at night were referred to as inyenzi ("cockroaches") due to their disappearance in the daylight. This dehumanising language was soon extended to the Tutsi population that still lived in Rwanda. The threat of the UNAR rebels to the Rwandan state was also exaggerated in the minds of the PARMEHUTU leadership and their supporters; rather than a multinational conspiracy, the raiding rebels were fractured and largely operated independently. Whilst their raids were a serious threat to the lives of civilians living in the border areas, as well as to security forces personnel, a Tutsi march on Kigali wasn't likely, at least without significant foreign support.

Juvénal Habyarimana

In July 1973, the Kayibanda government was toppled by a coup d'état headed by his defense minister, Major General Juvénal Habyarimana. Despite some initial overtures to the Tutsi population, Habyarimana soon reversed course to perpetuate the anti-Tutsi policies of his predecessor. In 1975, Habyarimana established his own political party, the Mouvement Révolutionnaire National pour le Développement (National Revolutionary Movement for Development, MRND) and outlawed all others. A 1978 constitution implemented by the MRND defined Rwanda as a presidential republic with no term limits. Habyarimana, the only name on the ballot, was also elected to a five-year term as President.

===

[224] IOTL Rwagasore was assassinated by a Greek national in the employ of the PDC. Details are uncertain, but it appears that the factor that pushed the PDC to go through with the assassination was encouragement by the Belgian resident. ITTL no Belgian resident, the PDC don't dare to kill Rwagasore without Western support.

[225] IOTL such economic modernisation wouldn't occur until the late 1970s and early 1980s under the purview of Jean-Baptiste Bagaza, a military dictator of Burundi.

[226] IOTL, the pro-Tutsi governments that came about in the aftermath of Rwagasore's assassination allowed these rebels to operate out of Burundi, which further inflamed ethnic tensions in Burundi itself.

[227] IOTL, a Hutu coup in 1965 toppled the Burundian monarchy, which went into exile and Mwambutsa himself ended up living out the rest of his life in Switzerland. ITTL, the monarchy isn't topped.

[228] IOTL this union was dissolved due to the post-Rwagasore Burundian government's harbouring of UNAR rebels.

Sadly it seems Rwanda falls to a military rule, hopefully this won't last long nor lead into the genocide

I can't give away too much, but even though Rwanda's fate has been pretty convergent with OTL thus far, it won't stay that way.Sadly it seems Rwanda falls to a military rule, hopefully this won't last long nor lead into the genocide

That's a relief to hearI can't give away too much, but even though Rwanda's fate has been pretty convergent with OTL thus far, it won't stay that way.

Chapter 97: The Crowned Crane Bows - Uganda (Until 1980) (Part 1)

The British protectorate of Uganda, in contrast to many of London's other African colonies, was unique in that it was organised into a system of sub-imperialism. After the imposition of British imperial sovereignty, the kingdom of Buganda had largely collaborated with the British against rival kingdoms such as the Bunyoro who had opposed the British. In the post-WWII environment, the native kingdoms jockeyed with the British around local authority. Other significant players in Uganda were the Ugandan Asians, immigrants and their descendants from Britain's South Asian holdings. These Ugandan Asians were given a monopoly over cotton-ginning, a major contributor to the Ugandan economy, due to a British belief that the racist assumption that the Asians were intrinsically more efficient and entrepeneurial. In 1949, disgruntled Baganda (the demonym of Buganda) rioted and burnt down the houses of pro-British chiefs. The rioters put forward three demands to the colonial authorities: the right to bypass government-instituted price controls on export sales of cotton; the removal of the Asian monopoly over cotton ginning; and the right to have their own representatives in local government replace British-appointed chiefs. They were also critical of the Buganda Kabaka (king), Frederick Walumgembe Mutesa II for his inattentiveness to the needs of his people. British governor, Sir John Hall, regarded the riots as the work of communist agitators and rejected the recommended reforms.

Kabaka Frederick Walumgembe Mutesa II, King of Buganda and first President of Uganda

Post-war British retreat from India, the rise of pan-Africanism and a more liberal British Colonial Office set Uganda on a path to self-rule. In 1952 Hall was replaced by the reformist Sir Andrew Cohen, former Undersecretary for African Affairs in the Colonial Office. The new government removed obstacles to African cotton ginning, rescinded price discrimination against African-grown coffee, encouraged cooperatives, and established the Uganda Development Corporation. He reorganised the legislative council to include native representatives from throughout Uganda. Political reform caused a sudden proliferation of political parties, alarming the old guard centred around the traditional kingdoms. A 1953 speech in London by Cohen referring to the possibility of an East African Federation in the vein of Rhodesia-Nyasaland worried Ugandans, who saw the Central African Federation (rightfully) as a vehicle for settler interests. Fearing dominance by the white Kenyan minority (as it turned out, this group would flee Kenya in the aftermath of Kenya's break-up), the political class amongst the Ugandan natives started to view Cohen's reforms with suspicious. Kabaka Mutesa II demanded that Buganda be separated from the protectorate and transferred to Foreign Office jurisdiction, effectively denying Cohen's authority over his kingdom. In response, Cohen had the Kabaka deported to London. This backfired spectacularly, as the once-unpopular Kabaka became a symbol of resistance amongst his people. The Baganda chiefs and administrative apparatuses of the kingdom mounted a two year campaign of obstructionism until Cohen relented and allowed the Kabaka to return to his homeland. Cohen managed to secure Mutesa's agreement to partipate in a future federal Ugandan state, but was forced to concede powers to Mutesa that the Baganda Kabaka hadn't held since 1889, namely the power to appoint and dismiss chiefs in his kingdom, who had prior been appointed by the British governor, effectively making the Kabaka an absolute monarch in his territories.

A new grouping of Baganda referring to themselves as "The King's Friends" rallied around the newly-empowered king. The King's Friends were conservatives who insisted on a primary position for the Buganda kingdom amongst the Ugandans, entertaining participation in a united Uganda only if the Buganda Kabaka was head of state. Another political force in Baganda was the Democratic Party (DP) which emerged from Catholics in Baganda. The Catholic Church had educated a small group of Baganda, including the DP leader Benedicto Kiwanuka. These Catholics felt excluded by the Protestant Baganda establishment (the Kabaka and other high-level positions had to be Anglicans by law). Elsewhere in Uganda, despite often divergent interests between the regions, political unity was prompted by opposition to Bugandan domination. Buganda, after all, composed 2 million of the 6 million total Ugandans. In 1960, Milton Obote, a leader amongst the Nilotic Langi people of northern Uganda, formed a broad-based party, the Uganda People's Congress (UPC), to represent the non-Baganda. That same year, the London Conference was held to outline the future contours of an independent Ugandan state. It quickly became clear that Bugandan autonomy and a strong unitary state were fundamentally incompatible, and no compromise was made. The British announced that they would hold elections in March 1961 for "responsible government", the penultimate step before independence.

Milton Obote, first Prime Minister and Second President of Uganda and head of the Uganda People's Congress

In Buganda, the "King's Friends" urged a total boycott of the election because their attempts to secure provision of future autonomy had been rebuffed by the British. Buganda was allotted 21 out of 82 seats in the National Assembly. Braving public pressure, DP supporters went out to the polls, and as such the Democratic Party won 20 out of 21 Buganda seats. They also won a number of seats outside of Buganda, and despite the UPC winning slightly more of the popular vote, the DP ended up with an artificial majority in the Ugandan legislature. Benedicto Kiwanuka became the first Chief Minister of Uganda, a post equivalent to the Prime Minister but in a not-yet-independent state. Immediately regretting their boycott of the elections, the King's Friends established a political party, the Kabaka Yekka (King Only, KY) and began voicing support for a federated Uganda. In order to take power from the DP, the UPC and KY entered into a marriage of convenience. They reached a compromise that in a coalition government, the Kabaka could appoint Buganda's representatives to the National Assembly, as well as Mutesa taking the position of ceremonial Head of State. This coalition defeated the DP government in the April 1962 election. The coalition took 67 seats (43 UPC, 24 KY) to the DP's 24. The UPC-KY coalition led Uganda into independence in October 1962, with Obote as Uganda's Prime Minister and Mutesa II as President. Whilst on paper the UPC was in a powerful position, in reality it was a full-time job for Obote. Notable regional party bosses in the UPC included Obote himself, George Magezi (who represented the Bunyoro), Grace Ibingira (of the Anhole Bantu people of Uganda's southwest), and the reactionary representative of the neglected West Nile district, Felix Onama. All of these figures expected the government to deliver material benefits for their people, as well as allowing them to exercise patronage and being granted a ministerial position. Furthermore, Obote's politically-motivated acknowledgement of Buganda's special status emboldened other groups to demand such status; the Busoga chiefdoms banded together to demand official recognition of their newly-defined monarch, the Kyabasinga. The Iteso people, who had never recognised a precolonial king, claimed the title "Kingoo" for their political boss, Cuthbert Joseph Obwangor.

In January 1964, Obote's authority was challenged by a mutiny of army officers. Like many other newly independent states in Africa, their armed forces demanded an increase in pay and promotions in exchange for stability. Onama, the Minister of Defense, went to speak with the mutineers face-to-face, but was promptly taken hostage. Obote acceded to the mutineers' demands, and he selected a popular junior officer, Idi Amin, to be his protégé. Amin would be frequently promoted over the next couple of years. Later that year, Ibingira mounted an intra-UPC challenge to Obote's leadership. Conspiring with Ibingira, Mutesa instructed KY MPs to join the UPC, planning to take over the party from the inside by forming an Ibingira-KY alliance. They were unable to pull off this hostile takeover, however, as before all the KY MPs could join the UPC, enough DP and other figures in the National Assembly had drifted over to UPC patronage networks, and Obote was able to dissolve the KY-UPC coalition whilst still maintaining a majority in the National Assembly. Obote finally felt strong enough to push against Buganda and limit their disproportionate power. The vehicle to do so was addressing the issues of the "lost counties" of Bunyoro. These counties had been transferred from Bunyoro to Buganda during the imposition of British authority in the region as a punishment for Bunyoro resistance and a reward for Bugandan collaboration with the imperial power. A plebiscite was held in the lost counties, which overwhelmingly came out in favour of reunification with Bunyoro. During the plebiscite, the Kabaka had mobilised 300 Baganda veterans to intimidate voters, but these were counteracted by the massing of 2,000 Bunyoro veterans on the frontier between the two kingdoms, an implicit threat of civil war in the event of the Kabaka interfering with the plebiscite. This also of course shifted the National Assembly seats from the lost counties outside of KY control. Ironically, the weakening of the perceived threat from Buganda caused some fraying inside the UPC. Dissatisfaction with the plebiscite outcome caused the KY to started agitating for Bugandan independence. Seeking to cow the centrifugal forces in the UPC and finally get the Kabaka in line, Obote ordered Idi Amin to arrest Mutesa II. The Baganda monarch was able to escape from his palace into exile, whilst many of his close advisors were killed as the government troops assaulted his palace. Outraged by this unilateral use of military force against a domestic political figure, DP, KY and many of the UPC representatives pushed through a no confidence vote in the National Assembly. Only the radical John Kakonge didn't vote against Obote. Opposition to the Prime Minister was greatest amongst the southern Bantu representatives. With Amin's assistance, Obote mounted a coup against his own government, and arrested opposition leaders. A new republican constitution was forced through and Buganda was divided into four geographically-defined districts and was placed under direct martial law. Mutesa II would die three years later in London under suspicious circumstances. The official story is that he died from self-inflicted alcohol poisoning, but individuals who saw him earlier that day noted his sobriety and good spirits. Many believe he was assassinated by being force-fed vodka by intruders.

Awon'go Idi Amin Dada, Third President (and Dictator) of Uganda

The UPC became the only legal party. Obote issued the "common man's charter", echoing Nyerere's call for African socialism. However the corrupt Obote placed economic nationalisation plans in the hands of an Asian millionaire who financed the UPC. Obote established a feared secret police, the innocuously-named General Service Unit (GSU). In December 1969 Obote was assassinated with a grenade detonation[229]. Amin immediately moved to take control of the country, claiming that he would punish the murderers, even though its highly likely that Amin himself was behind the assassination. Brigadier Pierino Okoya, one of Amin's only rivals amongst the senior officers, escaped with some loyal troops to neighbouring Tangyanika[230]. Amin quickly went to work arresting political opponents, falsely accusing them of a grand conspiracy against the late President, and having them executed.

===

[229] IOTL, the grenade didn't detonate. Amin would instead coup Obote in 1971 preemptively, as Obote realised that he was planning to take power.

[230] IOTL, Okoya would be assassinated, most likely on Amin's orders in 1970.

Kabaka Frederick Walumgembe Mutesa II, King of Buganda and first President of Uganda

Post-war British retreat from India, the rise of pan-Africanism and a more liberal British Colonial Office set Uganda on a path to self-rule. In 1952 Hall was replaced by the reformist Sir Andrew Cohen, former Undersecretary for African Affairs in the Colonial Office. The new government removed obstacles to African cotton ginning, rescinded price discrimination against African-grown coffee, encouraged cooperatives, and established the Uganda Development Corporation. He reorganised the legislative council to include native representatives from throughout Uganda. Political reform caused a sudden proliferation of political parties, alarming the old guard centred around the traditional kingdoms. A 1953 speech in London by Cohen referring to the possibility of an East African Federation in the vein of Rhodesia-Nyasaland worried Ugandans, who saw the Central African Federation (rightfully) as a vehicle for settler interests. Fearing dominance by the white Kenyan minority (as it turned out, this group would flee Kenya in the aftermath of Kenya's break-up), the political class amongst the Ugandan natives started to view Cohen's reforms with suspicious. Kabaka Mutesa II demanded that Buganda be separated from the protectorate and transferred to Foreign Office jurisdiction, effectively denying Cohen's authority over his kingdom. In response, Cohen had the Kabaka deported to London. This backfired spectacularly, as the once-unpopular Kabaka became a symbol of resistance amongst his people. The Baganda chiefs and administrative apparatuses of the kingdom mounted a two year campaign of obstructionism until Cohen relented and allowed the Kabaka to return to his homeland. Cohen managed to secure Mutesa's agreement to partipate in a future federal Ugandan state, but was forced to concede powers to Mutesa that the Baganda Kabaka hadn't held since 1889, namely the power to appoint and dismiss chiefs in his kingdom, who had prior been appointed by the British governor, effectively making the Kabaka an absolute monarch in his territories.

A new grouping of Baganda referring to themselves as "The King's Friends" rallied around the newly-empowered king. The King's Friends were conservatives who insisted on a primary position for the Buganda kingdom amongst the Ugandans, entertaining participation in a united Uganda only if the Buganda Kabaka was head of state. Another political force in Baganda was the Democratic Party (DP) which emerged from Catholics in Baganda. The Catholic Church had educated a small group of Baganda, including the DP leader Benedicto Kiwanuka. These Catholics felt excluded by the Protestant Baganda establishment (the Kabaka and other high-level positions had to be Anglicans by law). Elsewhere in Uganda, despite often divergent interests between the regions, political unity was prompted by opposition to Bugandan domination. Buganda, after all, composed 2 million of the 6 million total Ugandans. In 1960, Milton Obote, a leader amongst the Nilotic Langi people of northern Uganda, formed a broad-based party, the Uganda People's Congress (UPC), to represent the non-Baganda. That same year, the London Conference was held to outline the future contours of an independent Ugandan state. It quickly became clear that Bugandan autonomy and a strong unitary state were fundamentally incompatible, and no compromise was made. The British announced that they would hold elections in March 1961 for "responsible government", the penultimate step before independence.

Milton Obote, first Prime Minister and Second President of Uganda and head of the Uganda People's Congress

In Buganda, the "King's Friends" urged a total boycott of the election because their attempts to secure provision of future autonomy had been rebuffed by the British. Buganda was allotted 21 out of 82 seats in the National Assembly. Braving public pressure, DP supporters went out to the polls, and as such the Democratic Party won 20 out of 21 Buganda seats. They also won a number of seats outside of Buganda, and despite the UPC winning slightly more of the popular vote, the DP ended up with an artificial majority in the Ugandan legislature. Benedicto Kiwanuka became the first Chief Minister of Uganda, a post equivalent to the Prime Minister but in a not-yet-independent state. Immediately regretting their boycott of the elections, the King's Friends established a political party, the Kabaka Yekka (King Only, KY) and began voicing support for a federated Uganda. In order to take power from the DP, the UPC and KY entered into a marriage of convenience. They reached a compromise that in a coalition government, the Kabaka could appoint Buganda's representatives to the National Assembly, as well as Mutesa taking the position of ceremonial Head of State. This coalition defeated the DP government in the April 1962 election. The coalition took 67 seats (43 UPC, 24 KY) to the DP's 24. The UPC-KY coalition led Uganda into independence in October 1962, with Obote as Uganda's Prime Minister and Mutesa II as President. Whilst on paper the UPC was in a powerful position, in reality it was a full-time job for Obote. Notable regional party bosses in the UPC included Obote himself, George Magezi (who represented the Bunyoro), Grace Ibingira (of the Anhole Bantu people of Uganda's southwest), and the reactionary representative of the neglected West Nile district, Felix Onama. All of these figures expected the government to deliver material benefits for their people, as well as allowing them to exercise patronage and being granted a ministerial position. Furthermore, Obote's politically-motivated acknowledgement of Buganda's special status emboldened other groups to demand such status; the Busoga chiefdoms banded together to demand official recognition of their newly-defined monarch, the Kyabasinga. The Iteso people, who had never recognised a precolonial king, claimed the title "Kingoo" for their political boss, Cuthbert Joseph Obwangor.