You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Kistling a Different Tune: Commercial Space in an Alternate Key

Threadmarks

View all 52 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

RpK Logo, circa 2006 June 4, 2010: Falcon 9 Maiden Launch June 10, 2010: K-1 COTS Demo-2 (Unpressurized Cargo Demo) Launch June 13, 2010: K-1 COTS Demo 2 Berthing and Rocketplane XP First Rollout June 16, 2010: Iridium Contract Awarded K-1 Iridium Arrangement July 15, 2010: Senate Compromise on NASA Budget Introduced in Committee for Commerce, Science, and Transportation July 26, 2010: AIAA Propulsion Conference RpK and SpaceX presentationsChanges in the timeline don't seem to have impacted the budget proposal much if at all. Next question is if they impact the responses to the budget proposal....

Yeah, that's going to be a big question to see if it changes the political response for what happens...

I'm honestly a bit interested on the political response, and again, nice job with the 'snapshots' of the IRC-style chatting with the updates!

Changes in the timeline don't seem to have impacted the budget proposal much if at all. Next question is if they impact the responses to the budget proposal....

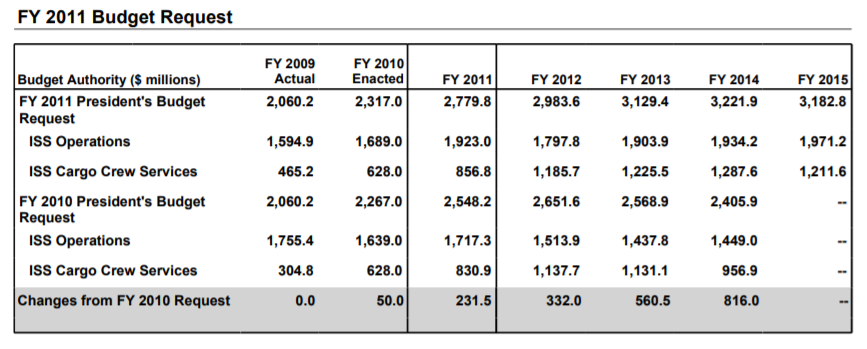

The budget proposal certainly hasn't changed much. It's the politics that have changed. The budget documents from TTL differ mostly on the line for "Space Operations" which deals with the budget for Commercial Cargo operational missions, among other things. IOTL, this was the rundown for details:Yeah, that's going to be a big question to see if it changes the political response for what happens...

I'm honestly a bit interested on the political response, and again, nice job with the 'snapshots' of the IRC-style chatting with the updates!

In this timeline, every year on the "ISS Crew Cargo Services line" is lower by about $142 million. The reasoning behind this is that IOTL, CRS contracts awarded in December of 2008 broke down like so:

SpaceX: 12 flights, $1.6 million

Orbital Sciences: 8 flights, $1.9 billion

These were minimum orders for flights between 2009 and 2016, with the total value of each contract being capped at $3.1 billion and a minimum upmass of 20 tons per provided. The total value for the two combined was $3.5 billion--obviously, they couldn't both get their maximum value.

ITTL, of course, Orbital Science isn't in the contract at all. A K-1 ISS mission probably runs about $35 million ($17 million base launch cost, $3 million in normal launch services, $10 million in additional station cargo module processing, and $5 million in NASA-related additional cost). Thus, a billion goes a long way--honestly, further than NASA needs. With lower costs, NASA does acquire more initially assured launches to the station during the 2010-2015 period, but at a lower overall cost:

SpaceX: 12 flights, $1.6 billion

RpK: 24 flights, $840 million

Elon will pitch a fit at K-1 being awarded twice as many assured flights as SpaceX, and RpK (and most notably minority investor and majority holder of political capital ATK) will pitch a fit that their orders total only half what SpaceX is getting in mission costs. NASA will view this as a good compromise and count a savings of $1 billion over OTL in spite of higher upmass. Annually, this amounts to about $140 million over the period covered by the contract, and the operations budget can be lower by this same amount.

Obviously, however, the real question is how the politicking plays out over the next year. Will there be an SDHLV? How will things shake out with CRS contracts and with the allocation of funding between Obama new priorities like technology demonstrations and exploration precursor missions? Will the K-1's successes pave the way for more reliance on commercial, or will the the ghost of Glushko return to haunt the NK-33 again and "prove" commercial advocates wrong? What do SpaceX and RpK have planned once they get flying?

....Stay tuned.

February 21, 2010: STS-130 Landing and 2010 Budget Reactions

The STS-130 mission was a perfect example of Space Shuttle assembly missions to the International Space Station. Over ten days at the station, the crew berthed the Node 3 module Tranquility to the port side of Node 1, reconfigured the Cupola module to its permanent nadir-facing position on Node 3 from its axial launch position, transferred the PMA-3 module from a temporary position on Node 2 Harmony to a new position at the axial (port) end of Node 3, and conducted three spacewalks to outfit Node 3 and the Cupola into their flight configuration. On Flight Day 10, the Cupola windows had been opened for the first time, granting a new and wider view of the world than had ever been available before through its seven windows, including a 36” main port looking directly down at the Earth below.

However, Endeavour’s 24th spaceflight was also officially to be her second to last--and as currently planned, the last mission of the entire Space Shuttle program. The Earth below might look peaceful, but as mission commander George Zamka and pilot Terry Virts guided Endeavour down over the coast of Washington en route to a landing at KSC, they swept over a country which was in the midst of a furious debate over the future of spaceflight beyond the end of the Shuttle. As many outside the White House had expected, but as had apparently come as a shock to Obama’s staff, the proposal to kill Constellation in the cradle and end development on a Shuttle-derived heavy lifter and the new Orion crew capsule entirely had not only come as an affront to spaceflight fans. It had also met with stark opposition by the powerful interests of the companies involved with those programs. Boeing, whose headquarters Endeavour flashed over at speeds above Mach 20, faced the end of their program for the development of the Ares V core stage, and the sudden absence of a replacement. It represented the loss of tens of billions in development funds and thousands of jobs in Alabama, New Orleans, and Florida. Lobbyists clustered, planning strategies to coordinate messaging over thwarting Obama’s plans to end Constellation--or at least to ensure that the replacement program would include some kind of Shuttle-derived heavy lifter.

The Shuttle itself flashed over these discussions in seconds, continuing on over northern Utah, passing the major operational center for yet another of America’s giants in spaceflight lobbying: ATK. Around ATK headquarters in Eden Park, Minnesota, reactions were somewhat mixed: the Obama plans called for a massive increase in funding for commercial supply of the International Space Station, a role their investment in RpK left them well-positioned to take advantage of, and which promised to end a continuing deadlock with RpK leadership over the contracts to begin integration for the second LAP and second and third OVs. The K-1 might also be positioned for a bid on the billions of dollars the Obama budget called to spend on the development of a commercial crew vehicle. However, a few hundred million here and there from the K-1 program could hardly replace the steady diet of Space Shuttle and Constellation pork for their flagship solid rocket program. And yet...the checks for Ares V and Ares I five-segment booster development (always the most lucrative portion of a program) had largely already been cashed. If a new HLV didn’t include these boosters, it might not be the end of the world as long as their development was completed.

Indeed, if such a new heavy lifter were to call for the use of reusability as demonstrated by RpK, ATK’s contracts and Michoud to manage assembly the K-1 and to conduct much of launch and turnaround operations at RpK’s Woomera launch site meant they were positioned to be the world leaders in integration and operation of reusable vehicles. If such a vehicle went forward, it might be possible for ATK to wrestle the contract for not just the boosters, but the prime contract for the entire vehicle--a prize worth several times the value of simply building five-segment boosters after development. The timing was wrong, however. No suitable engine yet existed for such a monster, and the K-1 was still beginning its early flights. The thought started off small, but began to spread inside the company’s Minnesota headquarters: perhaps there might be more value in Obama’s plans to wait on HLV development than their knee-jerk reaction had indicated, for ATK as a company, and thus certainly for the country as a whole. White-hot rhetoric began to cool as the thoughts circulated, and new calls went out to congressional and senate offices in Utah, Alabama, and Florida.

While lobbyists considered changes in direction below, Endeavour swept through her own graceful banking turns, bleeding off energy with the atmosphere flaring off her wingtips. Control surfaces and thrusters worked in harmony, all reacting to Zamka and Virts’ steady hand on the stick. This was the moments her design was born for. The delicate balance of air and heat had consumed hundreds of thousands of hours of computer time over the decades, and though the ballet might only occur a few more times, Endeavour’s pilot and computers knew all the steps. At hypersonic speeds tens of kilometers above Oklahoma City, the Space Shuttle Endeavour danced, leaving her characteristic sonic booms behind in her flaming wake as she swept on to Florida.

While she continued on to land, however, the team at RpK in Oklahoma City were planning for her replacement. As of that morning, the final closeouts for the K-1 COTS Demo 1 flight were beginning. Jean-Pierre Boisvert’s flight control team were in the simulator, working through the procedures to guide their spacecraft on to berth to the same node, if not the same port, which Endeavour ahd so recently freed up. Other engineers worked through weight and balance checklists with NASA teams in Houston as they planned the loadout for the low-risk cargos of opportunity which would be loaded into the Pressurized Payload Module to be unloaded if the K-1 succeeded in making its berthing to Station. The planned launch date had slipped from March 1st to March 3rd, but that still meant the launch of the next generation of reusable rocket to the space station was less than a week and a half away.

The K-1 was Endeavour’s successor in many ways. The K-1 was technological cousin using many of her systems or a child drawing on shuttle heritage for a fully reusable vehicle of the type Shuttle’s designers had dreamt to build. However,the K-1 lacked Shuttle’s grace in the air. While Endeavour’s sleek form danced with the air, the K-1 simply shoved it aside in frustration. The Shuttle, though long described as like flying a brick by pilots, at least had significant lift. Her massive wings, carried to orbit at the cost of so much payload, let her slip through the air with the relative agility she was once again putting to use to manage her return. The K-1 did not slip, cut, or knife through the air, not by a longshot. On return, the OV’s protective mantle of tiles and blankets wrapped its barrel-like form in the bare minimum required to sustain heat. The Space Shuttle was like flying a brick, but at least it flew. The OV’s return had all the grace of a brick thrown into a pond. The K-1 had even less respect for the air on ascent. Unlike the STS system’s careful ogives and booster noses, the K-1 offered the airstream the same blunt heat shield as on descent, shoving the airstream aside like a linebacker with the power of her AJ-26 main engines. And yet, if the mission proved successful in the coming weeks, the K-1’s two stages could go on to offer the Space Station the vehicle the Shuttle designers had always envisioned. Time would tell if she could weather the storm, not just of entry, but of politics.

While K-1 planners focused on their upcoming missions, Endeavour continued her return to Florida, knifing through the sky over Mississippi and Alabama. Below, at Huntsville, program managers and employees nervously considered what the end of Ares might mean for the center. There was little immediate hope in the 2010 budget, and the center’s employees and their representatives in Congress were beginning to marshall their efforts to fight for a reprieve for Ares. Orion, in the end, they could take or leave, but the heavy lifter and development efforts centered at Huntsville had to continue--there was too much on the line for anything else to happen. In Decatur, employees of ULA cursed that none of their proposals for COTS had been selected, offering no chance for their rockets to benefit from the money thrown to commercial cargo. Perhaps commercial crew, but that was the issue under the most fire from their comrades in industry at Marshall. In Florida itself, however, the issue was less grim. Contractors at United Space Alliance, Kennedy Space Center, and the Cape nervously eyes their continued employment too. However, the reality depended less on the vehicle--launching Shuttle, SDHLV, commercial, or other launchers could amount to much the same as long as the workforce was kept busy. As a songsmith might have put it “If the rockets go up, who cares where they come from?” Launching alone was important, whatever the program which was required to ensure a continuing flight rate, though continued crew programs would be nice for the additional employment requirements--or at least, that was the case being in calls made from phone numbers with 952 area codes. Endeavour was above it all, though, swinging into the landing pattern for the Space Shuttle Landing Facility and finally skidding off the last of her energy into heat in her brakes. Like the Space Shuttle program, Endeavour was rolling to a halt.

However, Endeavour’s 24th spaceflight was also officially to be her second to last--and as currently planned, the last mission of the entire Space Shuttle program. The Earth below might look peaceful, but as mission commander George Zamka and pilot Terry Virts guided Endeavour down over the coast of Washington en route to a landing at KSC, they swept over a country which was in the midst of a furious debate over the future of spaceflight beyond the end of the Shuttle. As many outside the White House had expected, but as had apparently come as a shock to Obama’s staff, the proposal to kill Constellation in the cradle and end development on a Shuttle-derived heavy lifter and the new Orion crew capsule entirely had not only come as an affront to spaceflight fans. It had also met with stark opposition by the powerful interests of the companies involved with those programs. Boeing, whose headquarters Endeavour flashed over at speeds above Mach 20, faced the end of their program for the development of the Ares V core stage, and the sudden absence of a replacement. It represented the loss of tens of billions in development funds and thousands of jobs in Alabama, New Orleans, and Florida. Lobbyists clustered, planning strategies to coordinate messaging over thwarting Obama’s plans to end Constellation--or at least to ensure that the replacement program would include some kind of Shuttle-derived heavy lifter.

The Shuttle itself flashed over these discussions in seconds, continuing on over northern Utah, passing the major operational center for yet another of America’s giants in spaceflight lobbying: ATK. Around ATK headquarters in Eden Park, Minnesota, reactions were somewhat mixed: the Obama plans called for a massive increase in funding for commercial supply of the International Space Station, a role their investment in RpK left them well-positioned to take advantage of, and which promised to end a continuing deadlock with RpK leadership over the contracts to begin integration for the second LAP and second and third OVs. The K-1 might also be positioned for a bid on the billions of dollars the Obama budget called to spend on the development of a commercial crew vehicle. However, a few hundred million here and there from the K-1 program could hardly replace the steady diet of Space Shuttle and Constellation pork for their flagship solid rocket program. And yet...the checks for Ares V and Ares I five-segment booster development (always the most lucrative portion of a program) had largely already been cashed. If a new HLV didn’t include these boosters, it might not be the end of the world as long as their development was completed.

Indeed, if such a new heavy lifter were to call for the use of reusability as demonstrated by RpK, ATK’s contracts and Michoud to manage assembly the K-1 and to conduct much of launch and turnaround operations at RpK’s Woomera launch site meant they were positioned to be the world leaders in integration and operation of reusable vehicles. If such a vehicle went forward, it might be possible for ATK to wrestle the contract for not just the boosters, but the prime contract for the entire vehicle--a prize worth several times the value of simply building five-segment boosters after development. The timing was wrong, however. No suitable engine yet existed for such a monster, and the K-1 was still beginning its early flights. The thought started off small, but began to spread inside the company’s Minnesota headquarters: perhaps there might be more value in Obama’s plans to wait on HLV development than their knee-jerk reaction had indicated, for ATK as a company, and thus certainly for the country as a whole. White-hot rhetoric began to cool as the thoughts circulated, and new calls went out to congressional and senate offices in Utah, Alabama, and Florida.

While lobbyists considered changes in direction below, Endeavour swept through her own graceful banking turns, bleeding off energy with the atmosphere flaring off her wingtips. Control surfaces and thrusters worked in harmony, all reacting to Zamka and Virts’ steady hand on the stick. This was the moments her design was born for. The delicate balance of air and heat had consumed hundreds of thousands of hours of computer time over the decades, and though the ballet might only occur a few more times, Endeavour’s pilot and computers knew all the steps. At hypersonic speeds tens of kilometers above Oklahoma City, the Space Shuttle Endeavour danced, leaving her characteristic sonic booms behind in her flaming wake as she swept on to Florida.

While she continued on to land, however, the team at RpK in Oklahoma City were planning for her replacement. As of that morning, the final closeouts for the K-1 COTS Demo 1 flight were beginning. Jean-Pierre Boisvert’s flight control team were in the simulator, working through the procedures to guide their spacecraft on to berth to the same node, if not the same port, which Endeavour ahd so recently freed up. Other engineers worked through weight and balance checklists with NASA teams in Houston as they planned the loadout for the low-risk cargos of opportunity which would be loaded into the Pressurized Payload Module to be unloaded if the K-1 succeeded in making its berthing to Station. The planned launch date had slipped from March 1st to March 3rd, but that still meant the launch of the next generation of reusable rocket to the space station was less than a week and a half away.

The K-1 was Endeavour’s successor in many ways. The K-1 was technological cousin using many of her systems or a child drawing on shuttle heritage for a fully reusable vehicle of the type Shuttle’s designers had dreamt to build. However,the K-1 lacked Shuttle’s grace in the air. While Endeavour’s sleek form danced with the air, the K-1 simply shoved it aside in frustration. The Shuttle, though long described as like flying a brick by pilots, at least had significant lift. Her massive wings, carried to orbit at the cost of so much payload, let her slip through the air with the relative agility she was once again putting to use to manage her return. The K-1 did not slip, cut, or knife through the air, not by a longshot. On return, the OV’s protective mantle of tiles and blankets wrapped its barrel-like form in the bare minimum required to sustain heat. The Space Shuttle was like flying a brick, but at least it flew. The OV’s return had all the grace of a brick thrown into a pond. The K-1 had even less respect for the air on ascent. Unlike the STS system’s careful ogives and booster noses, the K-1 offered the airstream the same blunt heat shield as on descent, shoving the airstream aside like a linebacker with the power of her AJ-26 main engines. And yet, if the mission proved successful in the coming weeks, the K-1’s two stages could go on to offer the Space Station the vehicle the Shuttle designers had always envisioned. Time would tell if she could weather the storm, not just of entry, but of politics.

While K-1 planners focused on their upcoming missions, Endeavour continued her return to Florida, knifing through the sky over Mississippi and Alabama. Below, at Huntsville, program managers and employees nervously considered what the end of Ares might mean for the center. There was little immediate hope in the 2010 budget, and the center’s employees and their representatives in Congress were beginning to marshall their efforts to fight for a reprieve for Ares. Orion, in the end, they could take or leave, but the heavy lifter and development efforts centered at Huntsville had to continue--there was too much on the line for anything else to happen. In Decatur, employees of ULA cursed that none of their proposals for COTS had been selected, offering no chance for their rockets to benefit from the money thrown to commercial cargo. Perhaps commercial crew, but that was the issue under the most fire from their comrades in industry at Marshall. In Florida itself, however, the issue was less grim. Contractors at United Space Alliance, Kennedy Space Center, and the Cape nervously eyes their continued employment too. However, the reality depended less on the vehicle--launching Shuttle, SDHLV, commercial, or other launchers could amount to much the same as long as the workforce was kept busy. As a songsmith might have put it “If the rockets go up, who cares where they come from?” Launching alone was important, whatever the program which was required to ensure a continuing flight rate, though continued crew programs would be nice for the additional employment requirements--or at least, that was the case being in calls made from phone numbers with 952 area codes. Endeavour was above it all, though, swinging into the landing pattern for the Space Shuttle Landing Facility and finally skidding off the last of her energy into heat in her brakes. Like the Space Shuttle program, Endeavour was rolling to a halt.

Ah, that is one detail I'd overlooked. How K-1 could affect not only how things happen in Congress, but those who build and operate (RpK/ATK) K-1 as well, since, as things stand currently, they have something already in place to take advantage of this particular direction should it go ahead. Those whose contracts were reliant on Ares I/V for Funding however...

Yeah, this is the secret of this particular TL and why I picked this particular PoD (one which preserved RpK, but with them tethered to ATK). I'm interested in Kistler's potential as a vehicle a lot and I have some thoughts on the future development of RpK and how that drives SpaceX to react, but I also really wanted to try out a radically different 2011 budget compromise--and given how hard ATK continued to push solid-first-stage launchers IOTL well past their sell-by date (Liberty and OmegAAAAAAA, anyone?), I knew I had to get them at least neutral on the concept of the K-1 and on waiting on an HLV. The question is for the compromise is: we found the start of ATK's price, but what's Nelson and Shelby's?Ah, that is one detail I'd overlooked. How K-1 could affect not only how things happen in Congress, but those who build and operate (RpK/ATK) K-1 as well, since, as things stand currently, they have something already in place to take advantage of this particular direction should it go ahead. Those whose contracts were reliant on Ares I/V for Funding however...

overninethousands

Banned

I really love this TL. Brilliantly done ! I have my own TL involving Rocketplane Kistler, where they are taken over in 2010 by a milionaire with the name of Elton Dusk (lame pun entirely assumed) which makes some serious cleaning at the company, much needed cleanup they badly needed...

Thank you! I appreciate it. I'm sort of interested in where you're planning to go with your TL, as by 2010 IOTL my understanding is that Rocketplane was pretty much dead...it'd take something like a half a billion to get them back up and on the track to hardware, especially as they've now blown out two generations of investors. Millionaire might not cut it, though a hundred-millionaire could with his entire fortune. It's also a little late to have a huge impact, I'd think, since ,it means they're unlikely to fly, whether orbital or suborbital, much before 2014 by which point a vehicle K-1's size isn't as attractive against the Falcon 9 as it is in 2010 against the Block 1--and it may be too late to get a seat at the table for CRS-2 or CCDev. How are you planning on tackling that? Do you have any speculation on where you think TTL might be going based on your ideas?I really love this TL. Brilliantly done ! I have my own TL involving Rocketplane Kistler, where they are taken over in 2010 by a milionaire with the name of Elton Dusk (lame pun entirely assumed) which makes some serious cleaning at the company, much needed cleanup they badly needed...

overninethousands

Banned

Well, it will be a little convenient... my fictional bilionaire will be half Bezos,half Musk with deep pockets.

Remember that book, The Rocket Company ? I'm inspired by it.

I currently have my head deep into early Internet history to see where I could get some billions for him There is no lack of bifurcations in Amazon, Paypal, or Google (smaller) competitors. One of of them could get big enough to fill my billionaire pockets. That's the basic idea.

There is no lack of bifurcations in Amazon, Paypal, or Google (smaller) competitors. One of of them could get big enough to fill my billionaire pockets. That's the basic idea.

Unlike your story, I consider Kistler needed serious cleanup - I don't like much Lauer and French. The bankruptcy is a way to move them out of the way. I want to pick up the pieces from both Kistler and... Rocketplane and start a saner, more efficient company. In fact my story is more about Rocketplane than Kistler. Not the XP, but rather Pathfinder.

IMTL (In My TL !) the K-1 is to gather experience in spaceflight and throw a wrench into the Musk - Bezos war, notably by flying long before November 2015, the day Bezos poked fun at Musk landing his New Shepard just ahead of Falcon 9.

Would it be realistic, from a 2010 start, to fly the first K-1 in spring 2014 ? the thing was 75% complete and French, for all his flaws, made a good job keeping up all the pieces together, in Michoud and elsewhere.

I remember all to well in the 90's and 2000s I was a die hard fan of the K-1 for the simple reason it was a deceptively simple way to achieve a 100% RLV - parachutes and airbags. Dumb, not elegant, but eminently workable. Much more than all those winged concepts.

thanks to this thread I learned a lot of interesting details. I knew for George Mueller involvement, but not that the K-1 was that well designed. Clever design, really. Also, they got 135 million for SLI in 2001 and SpaceX protested and won ? dang. And then they went bankrupt in July 2003...

Remember that book, The Rocket Company ? I'm inspired by it.

I currently have my head deep into early Internet history to see where I could get some billions for him

Unlike your story, I consider Kistler needed serious cleanup - I don't like much Lauer and French. The bankruptcy is a way to move them out of the way. I want to pick up the pieces from both Kistler and... Rocketplane and start a saner, more efficient company. In fact my story is more about Rocketplane than Kistler. Not the XP, but rather Pathfinder.

IMTL (In My TL !) the K-1 is to gather experience in spaceflight and throw a wrench into the Musk - Bezos war, notably by flying long before November 2015, the day Bezos poked fun at Musk landing his New Shepard just ahead of Falcon 9.

Would it be realistic, from a 2010 start, to fly the first K-1 in spring 2014 ? the thing was 75% complete and French, for all his flaws, made a good job keeping up all the pieces together, in Michoud and elsewhere.

I remember all to well in the 90's and 2000s I was a die hard fan of the K-1 for the simple reason it was a deceptively simple way to achieve a 100% RLV - parachutes and airbags. Dumb, not elegant, but eminently workable. Much more than all those winged concepts.

thanks to this thread I learned a lot of interesting details. I knew for George Mueller involvement, but not that the K-1 was that well designed. Clever design, really. Also, they got 135 million for SLI in 2001 and SpaceX protested and won ? dang. And then they went bankrupt in July 2003...

Last edited:

From what I can tell, the percent complete numbers that the different versions of Kistler often used were how much of the dry mass of the vehicle that they had produced, and from what I can tell, they were including the mass of the AJ26 engines in that. To that end, it really looks like the vehicle itself wasn't as complete as most people think when they hear "75% complete".Would it be realistic, from a 2010 start, to fly the first K-1 in spring 2014 ? the thing was 75% complete and French, for all his flaws, made a good job keeping up all the pieces together, in Michoud and elsewhere.

The solution I found in Rockwell Flyer is that they manage to get some investment in that period before the first bankruptcy.

overninethousands, I hope you don't mind if I shuffle your order around to reply, I think it'll work better with what I want to say:

It's not a bad evaluation to say that both Kistler Aerospace and Rocketplane Global had a problem with trying to run a small newspace startup like a multinational aerospace business, even moreso Kistler's "contract out literally everything" that Rocketplane's strategy, which did a lot more in house. However, Lauer and French do seem to have focused much more on the Rocketplane side, even as the K-1 and the COTS money was the shorter putt, and they didn't reprioritize until Kistler completely lost COTS...at which point they were hemorrhaging money and staff, and then decided to double down on the plane. You'll note even ITTL, they're being a little preferential to the Stupid Plane side of the company--the K-1's COTS milestone payments are being vacuumed off to help keep the plane's integration on track instead of starting to assemble the second set of LAP/OV hardware, a fact which is driving ATK up a wall and may even be annoying NASA. Much like you, they seemed to regard K-1 as a quick way to get flying, and the Rocketplane as the real focus.Unlike your story, I consider Kistler needed serious cleanup - I don't like much Lauer and French. The bankruptcy is a way to move them out of the way. I want to pick up the pieces from both Kistler and... Rocketplane and start a saner, more efficient company.

I think so. About 3-4 years seems about right. The actual vehicle integration process is probably only about two years, and building out the launch site is probably something similar (though this may depend on site prep--it took something insane like a year and a half to let soil compactify at Boca Chica before they could start leveling off the pad). The reason I'd say it's more like the 4-year side of the range is because of the loss of team members between 2006 and 2010. Having all the IP and parts is one thing, but having very very few of the actual engineers and technicians means to a certain extent you have to pick the design up from scratch--a research project stacked on top of a build project. That means a lot of research and a lot building the right team before you start the ~2-2.5 year clock on the way to launch. It's why I figured that the original RpK goal of flying by the end of 2008 for COTS IOTL probably wouldn't hold, and had the K-1 risk reduction demo mission in late 2009 instead.Would it be realistic, from a 2010 start, to fly the first K-1 in spring 2014 ? the thing was 75% complete and French, for all his flaws, made a good job keeping up all the pieces together, in Michoud and elsewhere.

I know, right? The K-1 is a tragedy not of engineering overreach (if anything, it's astoundingly conservative in design), but of luck and finance. I wanted to give it a spotlight, and make it a critical lever at this moment of history--the 2011 budget decision.I remember all to well in the 90's and 2000s I was a die hard fan of the K-1 for the simple reason it was a deceptively simple way to achieve a 100% RLV - parachutes and airbags. Dumb, not elegant, but eminently workable. Much more than all those winged concepts.

thanks to this thread I learned a lot of interesting details. I knew for George Mueller involvement, but not that the K-1 was that well designed. Clever design, really. Also, they got 135 million for SLI in 2001 and SpaceX protested and won ? dang. And then they went bankrupt in July 2003...

The semi-SSTO, semi-TSTO with an expendable second stage dropped off an aerial-fueled rocketplane that then boosts to just barely shy of LEO? That's really one of those pseudo-SSTO two stage designs that make you wonder why they don't just take the same technology and go build a TSTO that'd out-perform it... 2.1 tons for "only" $7 million is basically the same cost per kg as the K-1 they're already flying, and there's ways to make the K-1 cheaper if you...well, that might be getting a bit ahead of the TL.In fact my story is more about Rocketplane than Kistler. Not the XP, but rather Pathfinder.

February 25th: K-1 COTS Demo 1 Preparations

Sixty five days after its maiden launch, the RpK and ATK Woomera teams were gearing up to fly again. It had been just over fifty days since most of the team had returned from holiday vacations, but ever since the K-1 operations staff had been working every day, some nights, and the occasional weekend to see the rocket ready to prove the great unknown of the K-1 system: its complete and rapid reuse. There was little room for error. Unlike other companies, the K-1 team had no margin for “learning incidents,’ at least not any which resulted in a loss of vehicle, and the entire corporate strategy depended on rapidly beginning their two dozen missions to serve the International Space Station. With the much-bemoaned diversion of COTS progress funding awards to help hold schedule on Rocketplane integration back stateside, the Woomera team’s continued success would have to come from their own success--further funding for K-1 vehicles and future projects would be funded by successful K-1 missions to station. For that to begin, their COTS Demo flights had to succeed.

Events stateside had another effect--the world of spaceflight had changed a lot in fifty days. It was long enough for a president to propose a budget which would make commercial vehicles like the K-1 a crown jewel of American spaceflight, inspiring new zeal in vultures circling for any lapse or show of weakness by RpK or their commercial competitors at SpaceX. At a college in Ohio, fifty days was long enough for a freshman student to meet with an astronaut who told them to look into commercial, to suffer a personal crises, and to begin to question if--and how--their dreams might still be achieved. While the Kistler operations staff had labored in the confines of the hangar facilities at Woomera, the attention from the world had turned the pressure up to eleven.

Inside the hangar, the small tasks wrapped up and accumulated into large ones. The Pressurized Cargo Module loading commenced on the 15th. Like tangrams or Tetris blocks, carefully selected racks and cargo bags were loaded through the “back” hatch of the module. Walking on work platforms to the hatch cut into the aft end of the module, moving between the forward thrusters in bunny suits and booties, technicians loaded carefully documented materials into the confines of the K-1’s hold. This was in many ways a dry run. The racks loaded held no critical equipment, no GLACIER freezers or new experiments, and the bags of water and provisions loaded into the remainder of the module were surplus to station needs. Freshly topped off by Endeavour the week before, the supplies were useful, but not critical. Two smaller but unique payloads were last to be loaded, just before the hatch was bolted closed to form the aft bulkhead of the pressure vessel. One had flown in with an RpK executive and a bodyguard, while the latter had been picked up by a pair of interns at a local store to fit the flight plan. The former was heavy enough to require two technicians to help maneuver it into its slot in the carefully planned Tetris board that was the small cargo volume, while the other was lifted one-handed and passed over the threshold to be tied down. The skin-flint payload planning meant only the latter was intended for the crew themselves, while the former were to be returned to the ground.

The mission’s preparations went off like putting away a set of Russian nesting dolls. With the internal cargo loading complete, technicians could focus on the module’s exterior. The thrusters were tested and verified, the CBM boresight cameras were installed and checked, and the Kistler Proximity Operations Detection System (K-PODS) was powered on and verified working, both its Kurs radar and TriDAR LIDAR system. The the PCM was moved out into the main integration hangar, leaving the inner sanctum of the booties-only cleanrooms for the shirtsleeves-and-steel-toes realm of the main hangar where the untried forward payload module could be mounted to the OV propulsion unit and integrated into a single orbital spacecraft with the connections of power and data cables. The scale of the hardware being integrated escalated rapidly, from the loading of cargo bags massing a few kilograms to the OV and PCM massing tons. Finally on February 24th, the OV and LAP were aligned on the main integration rails and brought together. Technicians swarmed with torque wrenches and wire harnesses, binding the two vehicles together into one flight ready stack over the next day. Just 65 days from the maiden flight of the system, almost the entire same stack was ready to go--this time, to prove the vehicle’s suitability for the tremendous role commercial would have to play in the President’s commercial vision.

The risk reduction flight had proven the K-1 could fly, but this mission would bring new challenges. To reach the station’s orbit, the K-1 needed to fly at just the right moment, down to seconds of precision. Any delays would mean waiting a day or more, waiting for precession to carry the ground track of the station back over the launch site to the proper location. Moreover, while for simple orbital delivery missions for satellites the K-1 could literally fly itself, receiving no uploaded commands after launch until a wind report prior to entry, the complexities of an approach to the space station would put real responsibility in the hands of Jean-Pierre’s controllers in Oklahoma City. Like a human pilot, the vehicle’s avionics could still be trusted to carry out individual maneuvers, but the planning and optimization of the trajectory to chase down the station, bring the vehicle to rendezvous, and carry out the final approach while still leaving margin for departure and deorbit would require humans--and the more powerful ground-based computers--in the loop.

As the launch date--March 6th, 2010, 11:52:32 UTC--drew near, Woomera’s population exploded as it had before the maiden flight. The ELDO Hotel bar began to fill in the evenings as the old blockhouses became crowded, both by those involved in the launch and those just there to watch. Sightseers, some native Australians, some from as far away as the US or Europe, began to converge on the tiny Australian town, while representatives of NASA’s oversight and operations teams for station and COTS arrived in button-down shirts and polos. During the day, serious discussions flowed around the vehicle as it rolled out to the pad and the crews carried out the wet dress rehearsals and hardware-in-the-loop simulations required. The data rolled in, feeding the ongoing Flight Readiness Review as item after item was checked off as good for flight. As the launch day closed in, dozens of criteria for safe approach to the station’s keep-out sphere (KOS) still remained open, but many could not be settled until the K-1 and its PCM were in space. At night, the hotel bar and the town’s bowling alley offered a minimal distraction from the next day’s preparations, enough to inspire more than one LAN game or minor hijinx. The ELDO bar’s refrigerator, already home to a “Thales Australia” sticker, acquired a Rocketplane Kistler decal and a copy of the NASA meatball as the last days counted down to launch. Woomera, the once and future spaceport, was officially back on the map.

Events stateside had another effect--the world of spaceflight had changed a lot in fifty days. It was long enough for a president to propose a budget which would make commercial vehicles like the K-1 a crown jewel of American spaceflight, inspiring new zeal in vultures circling for any lapse or show of weakness by RpK or their commercial competitors at SpaceX. At a college in Ohio, fifty days was long enough for a freshman student to meet with an astronaut who told them to look into commercial, to suffer a personal crises, and to begin to question if--and how--their dreams might still be achieved. While the Kistler operations staff had labored in the confines of the hangar facilities at Woomera, the attention from the world had turned the pressure up to eleven.

Inside the hangar, the small tasks wrapped up and accumulated into large ones. The Pressurized Cargo Module loading commenced on the 15th. Like tangrams or Tetris blocks, carefully selected racks and cargo bags were loaded through the “back” hatch of the module. Walking on work platforms to the hatch cut into the aft end of the module, moving between the forward thrusters in bunny suits and booties, technicians loaded carefully documented materials into the confines of the K-1’s hold. This was in many ways a dry run. The racks loaded held no critical equipment, no GLACIER freezers or new experiments, and the bags of water and provisions loaded into the remainder of the module were surplus to station needs. Freshly topped off by Endeavour the week before, the supplies were useful, but not critical. Two smaller but unique payloads were last to be loaded, just before the hatch was bolted closed to form the aft bulkhead of the pressure vessel. One had flown in with an RpK executive and a bodyguard, while the latter had been picked up by a pair of interns at a local store to fit the flight plan. The former was heavy enough to require two technicians to help maneuver it into its slot in the carefully planned Tetris board that was the small cargo volume, while the other was lifted one-handed and passed over the threshold to be tied down. The skin-flint payload planning meant only the latter was intended for the crew themselves, while the former were to be returned to the ground.

The mission’s preparations went off like putting away a set of Russian nesting dolls. With the internal cargo loading complete, technicians could focus on the module’s exterior. The thrusters were tested and verified, the CBM boresight cameras were installed and checked, and the Kistler Proximity Operations Detection System (K-PODS) was powered on and verified working, both its Kurs radar and TriDAR LIDAR system. The the PCM was moved out into the main integration hangar, leaving the inner sanctum of the booties-only cleanrooms for the shirtsleeves-and-steel-toes realm of the main hangar where the untried forward payload module could be mounted to the OV propulsion unit and integrated into a single orbital spacecraft with the connections of power and data cables. The scale of the hardware being integrated escalated rapidly, from the loading of cargo bags massing a few kilograms to the OV and PCM massing tons. Finally on February 24th, the OV and LAP were aligned on the main integration rails and brought together. Technicians swarmed with torque wrenches and wire harnesses, binding the two vehicles together into one flight ready stack over the next day. Just 65 days from the maiden flight of the system, almost the entire same stack was ready to go--this time, to prove the vehicle’s suitability for the tremendous role commercial would have to play in the President’s commercial vision.

The risk reduction flight had proven the K-1 could fly, but this mission would bring new challenges. To reach the station’s orbit, the K-1 needed to fly at just the right moment, down to seconds of precision. Any delays would mean waiting a day or more, waiting for precession to carry the ground track of the station back over the launch site to the proper location. Moreover, while for simple orbital delivery missions for satellites the K-1 could literally fly itself, receiving no uploaded commands after launch until a wind report prior to entry, the complexities of an approach to the space station would put real responsibility in the hands of Jean-Pierre’s controllers in Oklahoma City. Like a human pilot, the vehicle’s avionics could still be trusted to carry out individual maneuvers, but the planning and optimization of the trajectory to chase down the station, bring the vehicle to rendezvous, and carry out the final approach while still leaving margin for departure and deorbit would require humans--and the more powerful ground-based computers--in the loop.

As the launch date--March 6th, 2010, 11:52:32 UTC--drew near, Woomera’s population exploded as it had before the maiden flight. The ELDO Hotel bar began to fill in the evenings as the old blockhouses became crowded, both by those involved in the launch and those just there to watch. Sightseers, some native Australians, some from as far away as the US or Europe, began to converge on the tiny Australian town, while representatives of NASA’s oversight and operations teams for station and COTS arrived in button-down shirts and polos. During the day, serious discussions flowed around the vehicle as it rolled out to the pad and the crews carried out the wet dress rehearsals and hardware-in-the-loop simulations required. The data rolled in, feeding the ongoing Flight Readiness Review as item after item was checked off as good for flight. As the launch day closed in, dozens of criteria for safe approach to the station’s keep-out sphere (KOS) still remained open, but many could not be settled until the K-1 and its PCM were in space. At night, the hotel bar and the town’s bowling alley offered a minimal distraction from the next day’s preparations, enough to inspire more than one LAN game or minor hijinx. The ELDO bar’s refrigerator, already home to a “Thales Australia” sticker, acquired a Rocketplane Kistler decal and a copy of the NASA meatball as the last days counted down to launch. Woomera, the once and future spaceport, was officially back on the map.

75 days from launch to launch is a bit longer than the target of just 9 days, but is a good start, and only a few times did any one orbiter see a turn-around in less time (from what I remember, Challenger, Discovery, and Atlantis each did it once), and to do a sub-90 day turn around after the first launch bodes well for the program's ability to learn and improve.

overninethousands

Banned

Compared to a Space Shuttle immense complexity, the K-1 is very much a Piper Cub or Cessna 172.

Compared to a Space Shuttle immense complexity, the K-1 is very much a Piper Cub or Cessna 172.

Is is really however?

The first stage boosts back, and lands via parachutes.

The second stage, on orbit has two sets of engines (just like the shuttle), as well as an RCS system for three axis control, and the SSMEs have demonstrated in the AR-22 tests rapid turn around. Furthermore, both the OV and the shuttle had reusable TPS that has to be checked. The K-1 does have slightly simpler power systems (batteries vs fuel cells), and no need for APUs (no aerodynamic control surfaces and the doors are electric, not hydraulic), but in terms of actual complexity, it's probably about the same. Where the K-1 OV differs from the shuttle is size - the orbiter (thanks to the wings) has multiples of the OV's surface area that have to be checked on TPS inspections.

Compared to a Space Shuttle immense complexity, the K-1 is very much a Piper Cub or Cessna 172.

Is is really however?

The first stage boosts back, and lands via parachutes.

The second stage, on orbit has two sets of engines (just like the shuttle), as well as an RCS system for three axis control, and the SSMEs have demonstrated in the AR-22 tests rapid turn around. Furthermore, both the OV and the shuttle had reusable TPS that has to be checked. The K-1 does have slightly simpler power systems (batteries vs fuel cells), and no need for APUs (no aerodynamic control surfaces and the doors are electric, not hydraulic), but in terms of actual complexity, it's probably about the same. Where the K-1 OV differs from the shuttle is size - the orbiter (thanks to the wings) has multiples of the OV's surface area that have to be checked on TPS inspections.

No, the K1 is NOT a "Piper Cub or Cessna 172" on comparison. It's a complex and finicky space craft which means it's more apt to say the Shuttle is the XB-70 and the K1 is the SR-71. Sure it's got some less complexity and servicing issues but as noted not that many. One of my pet peeves on the F9 is the idea that it will every be "gas-n-go" because it won't. Period. Likely no orbital launch vehicle will for a very long time because they are NOT airplanes and never will be. Much less higher performance vehicles such as SS2 and RPK can have similar 'turn-around' to an airplane because in the end they ARE airplanes but very high performance ones. They really are not space craft. New Sheppard is likely to have a pretty quick turn around but while it's a complex and finicky rocket ship it's not a very high performance one so again that makes things easier.

At this point and time, (or even today) if you want "aircraft like" operations then you pretty much have to USE an aircraft not a space craft otherwise you take more time because it's FAR less forgiving operational environment.

Randy

overninethousands

Banned

The neat thing with the K-1 is that, unlike New Glenn and Falcon 9, second stage is reusable. In your face, Musk and Bezos ! Of course the K-1 did not launched payloads to GEO, hence stage 2 only has to come back from LEO (which is already dauting enough). Plus K-1 payload was small (10 000 pounds).

The neat thing with the K-1 is that, unlike New Glenn and Falcon 9, second stage is reusable. In your face, Musk and Bezos ! Of course the K-1 did not launched payloads to GEO, hence stage 2 only has to come back from LEO (which is already dauting enough). Plus K-1 payload was small (10 000 pounds).

Actually New Glenn hasn't flown yet and from the designs I've seen it my in fact have a fully reusable second stage

Randy

overninethousands

Banned

That was Kisler solution to the issue. Not reusable, obviously.

http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2002iaf..confE.950L

http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2002iaf..confE.950L

But this still isn't going to allow them to compete in the geostationary launch market. Geostationary comsats are big (as in, 3000+ kg in most cases), and they kind of need to be big to be useful. The K-1 can send a maximum of 1500 kg to GTO (worse for a super-synchronous trajectory), which isn't enough to compete with Arianespace and, (hopefully) later, SpaceX for the big commercial launches. They're going to need to design a whole new vehicle to try and address that market, and designing new vehicles takes time. No, I've said it before and I'll say it again: K-1's big success here, in the near term, is not going to be in eating Arianespace/SpaceX's market (CRS contracts notwithstanding). It's going to be in eating PSLV's market. That kind of small, light payload is exactly what the K-1 was designed to launch. Let's not go looking for markets for K-1 to compete in when they've already got one.That was Kisler solution to the issue. Not reusable, obviously.

http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2002iaf..confE.950L

Threadmarks

View all 52 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

RpK Logo, circa 2006 June 4, 2010: Falcon 9 Maiden Launch June 10, 2010: K-1 COTS Demo-2 (Unpressurized Cargo Demo) Launch June 13, 2010: K-1 COTS Demo 2 Berthing and Rocketplane XP First Rollout June 16, 2010: Iridium Contract Awarded K-1 Iridium Arrangement July 15, 2010: Senate Compromise on NASA Budget Introduced in Committee for Commerce, Science, and Transportation July 26, 2010: AIAA Propulsion Conference RpK and SpaceX presentations

Share: