Story of a Party - Chapter II

"Henceforth, the watchword of every uncompromising abolitionist, of every friend of God and liberty, must be, in a religious as well as political sense - 'NO UNION WITH SLAVEHOLDERS' "

- William Lloyd Garrison

From "The Great Pathfinder" by Abraham Richardson

Yale University Press, 1954

"Around the time of the Minnesota compromise, another issue had sprung up and caught the attention of everyone in the United States: William Walker, an American filibuster, had returned from his first expedition to Nicaragua, where he had installed himself as President, and had been driven out by forces of the neighbouring states. His government had been recognised by President Pierce as the rightful one in that nation, and as such there were many calls for sending him aid for his next expedition, which he was planning at the time. The people who were most strongly in favour of this were democrats, both Southerners like Breckinridge and "dough-faces" like Buchanan. The Republicans were mostly against aiding the expedition, claiming it to be a violation of international law and a dangerous attempt to extend slavery. President Fremont himself, however, were rather ambivalent. He was a well-known frontiersman, and his belief in Manifest Destiny was well-known. He believed that supporting an incursion into Nicaragua, and eventually the other Central American nations, might both create a temporary diversion from the slavery issue, buying the Republican congressmen time to work out new legislation, and eventually, should those areas be annexed into the United States, additional counterweight to the Southern voters who favoured the extension of slavery. On the other hand, however, Walker was a southerner, and his intent in conquering Nicaragua had been to get annexed to the United States, extending slavery into new areas. It was very likely that Walker would refuse any offer of annexation that did not include the provision of making Nicaragua a slave territory.

The decision Fremont made, for whatever reason, was to talk to Walker and see if any bargain could be struck…"

***

The White House

Washington, D.C., United States

12 September 1857

"… so thus is my predicament, Mr President", William Walker said. "My expedition was thrown out of Nicaragua not by the Costa Rican army, as the penny press has it, but by the U.S. Navy! Is there any explanation for this?"

"Calm down" Fremont replied. "This was all in motion before I entered office. If anything, you should be shouting down Mr. Pierce."

"You know as well as I do that he is in Europe with his wife [1]." Walker added. "But that is of no importance. Now, Mr President, I know that you and I are made of the same stuff. We both explored and filibustered in the Mexican desert back in the '40s, only that the parts I captured didn't join the U.S. after the war. So I'm sure that you feel the same way as I do about this expedition. Nicaragua would be an excellent addition to our Union. It has excellent fields, high mountains no one has ever seen the top of, and, most important of all, there is a huge lake in the middle of it, that almost straddles the coastline on one side. It would be an excellent place to build a canal, and that could be significant help to your home state [2]."

"Your proposal has merit, Mr. Walker. Unfortunately, I am worried by your intents. Last time you took the country, you re-instituted slavery there. I want you to know that any venture to extend the institution of slavery to Nicaragua will be vehemently opposed by my government, and by the Republican party."

Walker knew that, of course, and it was true that he did want to establish the peculiar institution in Nicaragua. However, he had not quite had the chance to evaluate the land before he was booted out of the country, and it might well turn out that slavery would be unprofitable. After some thinking, he answered. "Well, Mr President, I shall have to come back to you on that point, once we have surveyed the land more closely. This will, of course, require our expedition to succeed."

Fremont took Walkers less than subtle hint immediately, replying: "Alright, then. I will propose a deal to you. You will receive some food supplies, and all of your men will be outfitted with army-issue rifles. Once you have left us a guarantee that you will not enslave any citizen of Nicaragua or bring any slaves into the country, we will grant you some financial aid and an offer of annexation."

"Mr President, I think we have a deal."

***

From "William Walker: A Biography" by Joseph Martin

Hiedler Publishing, Idaho, Shoshone, 1966

"After receiving support from Fremont, William Walker and his band of soldiers left the United States for Nicaragua. Once they arrived in San Juan del Sur, they easily defeated the local garrison there and sailed up the river using a small armed motorboat that they had carried aboard their ship. The distance up San Juan River was covered readily, and they managed to cross Lake Nicaragua and land at the smouldering ruins of Granada [3].

There, they found a Costa Rican army waiting for them. The Costa Ricans had gotten an advanced warning of Walker's second expedition, and had marched what remained of their old volunteer force back to Granada. Walker and his men were prepared for such an eventuality, and their new armaments proved their worth against the motley group of barely trained soldiers the Costa Ricans had outfitted. It was a long fight, but in the end, when the Napoleon gun the filibusters had purchased from an arms dealer in Savannah, Georgia and brought with them all the way was uncovered, most of the Costa Ricans fled. General Cañas of the Costa Rican army, seeing his troops running through the countryside, had no choice but to surrender. Walker now controlled Nicaragua once again, but he would face new enemies before his rule was stabilised…"

From "The Great Pathfinder" by Abraham Richardson

Yale University Press, 1954

"When news came to Washington of Walker's success, the Southern politicians cheered on the prospect of adding another slave state to the Union, and the Northerners were unsettled at the attempts to do this. The Republicans, who had reluctantly agreed to Fremont's proposal of aiding Walker, now hoped that he would emancipate, as he had informally promised Fremont he would do. When no such notice reached them, the decision was made to impose trade restrictions on Walker's government. There were even proposals for an outright blockade on Nicaragua's coasts. These plans were, however, rebuffed by Fremont, who believed that a better idea was to try to double-cross Walker into accepting annexation as a free territory. Walker was dealing with internal affairs, and had no time to conduct foreign policy.

Fremont did not fret over the lack of response from Walker, however. He had more than his share of work settling down the 'Bleeding Kansas' crisis, and preparing an act to reverse Kansas-Nebraska…"

***

From "From Washington to Fremont: A Political History of the Antebellum United States, 1789-1858"

By Professor Josiah Porter

University of North California Press, 1957

"By the Kansas-Nebraska Act, Kansas Territory had been formed, and like the rest of the West, its fate as slavery regards was to be determined by popular vote. Since Kansas was more heavily settled than Nebraska, and was surrounded entirely by slave states but populated mostly by settlers from free states, this situation quickly escalated into a crisis, when settlers arrived from Missouri to try and spread slavery into the new areas.

The first Missourians to arrive in Kansas were the so-called "border ruffians", who occupied Lecompton (the territorial capital) long enough to force the election of a pro-slavery legislature. In defiance of the resulting lack of representation, the local free-soilers held conventions starting in 1855, at which they put forth different plans for ensuring the eventual freedom of Kansas State. The arrival of slavers and pro-slavery farmers as settlers in the territory, which continued through the years, caused these meetings to be subject to violent opposition, that manifested itself in the Lecompton Massacre of November 1857, as the assembled free-soilers were viciously attacked by pro-slavery settlers and border ruffians.

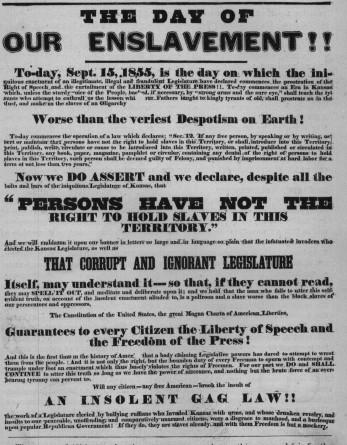

A free-soiler poster from 1855.

The Massacre led to the declaration of martial law in Kansas, and the deployment of a regiment of federal troops in the territory. This only served to further anger the pro-slavery settlers, who began openly referring to the government as "those abolitionist scum" and Fremont as "the fiend in the White House". A raid was conducted against the temporary regimental armoury that had been established in Topeka, aiming to release government issue weapons among pro-slavery farmers, to march on Lecompton and force the territorial government to declare Kansas a slave territory. This raid was firmly rebuffed by federal troops, narrowly avoiding turning the unrest into open civil war.

After this event, the army tightened its control of the countryside, and the local free-soilers, led by John Brown, aided the federal troops in bringing down the pro-slavery forces, who were increasingly being viewed as terrorists, and restoring order. Eventually, in June of 1859, the legislature, now controlled by the free-soilers, began work on a constitution for a new Kansas State, to be admitted into the Union by act of Congress."

***

From "The Great Pathfinder" by Abraham Richardson

Yale University Press, 1954

"On March 14, 1858, right when the Bleeding Kansas crisis was at its height, the Republican Congressmen, led by House Majority Leader Nathaniel Banks of Massachusetts, announced that they were finished drafting the so-called "New West" bill, which would reorganise the American West into a series of territories slightly smaller than the present ones, an action that, it was hoped, would reduce lawlessness by moving local governments closer to settlers. However, the bill was tabled in a vote, since the Republicans lacked a majority in the Senate and the Democrats had voted against it, as all the territories in the West were to be free-soil. The bill was not modified by the Republicans for two reasons: firstly, they did not want to concede any land to popular sovereignty, and secondly, the Kansas crisis was not over yet. However, that summer, with the gradual victory of the free-soilers in Kansas, work was slowly resumed on the revised bill, but it was not finished until November, just in time for the congressional midterm election."

***

From "A Complete History of the United States Congress"

Complied by the Library of Congress, 1955

"1858 midterm election

The 1858 midterm election was a surprisingly anticlimactic moment in all the chaos that was engulfing the United States at the time. After Bleeding Kansas, "Bleeding Sumner" [4], the presidential election of 1856 and the Nicaragua expedition, everyone expected rough, almost violent campaigning, but the elections were generally quite calm, and people went to the polls as usual. When the ballots were counted, the big winners were the Republicans, who gained seats in the House and finally achieved a majority in the Senate, together with the Northern Know-Nothings, who were increasingly becoming a wing of the Republicans. Now, 35 of 65 [5] Senate seats, and 121 of 233 House seats. For a full list of Congressmen during the 35th Congress, see the "Lists" section."

***

Taken from "From Washington to Fremont: A History of Antebellum United States Politics 1789-1858"

By Professor Josiah Porter

University of North California Press, 1957

"Worthy of particular note was the Illinois senatorial contest. Senator Stephen Douglas' seat was up for reelection, and Abraham Lincoln contested the seat for the Republicans. Douglas was favoured by people from the south of the state, as well as a few big business owners, and Lincoln was liked by small-time business owners (who still dominated the Illinoian landscape), northerners, as well as the Republican-majority [6] General Assembly, the state legislature. While Lincoln would most likely be elected by the General Assembly, the senatorial election would take place once the new Assembly had taken office, and after some debating, Lincoln and Douglas decided to hold formal debates once in every congressional district except Chicago and Springfield, where both had already spoken. The debates quickly became public spectacles, and masses of visitors came to each one to hear what the major parties had in store for Illinois, and about the future of slavery, which quickly became the principal subject of the debates.

In the end, the Republicans won the election this time again, sending Lincoln to the Senate, and disgruntling Douglas into a period of inaction. With a majority delegation, including Lincoln, in the Senate to defend the Republican colours in the face of popular sovereignty, the future of slavery in the Union was secured at a stroke."

***

From "The Great Pathfinder" by Abraham Richardson

Yale University Press, 1954

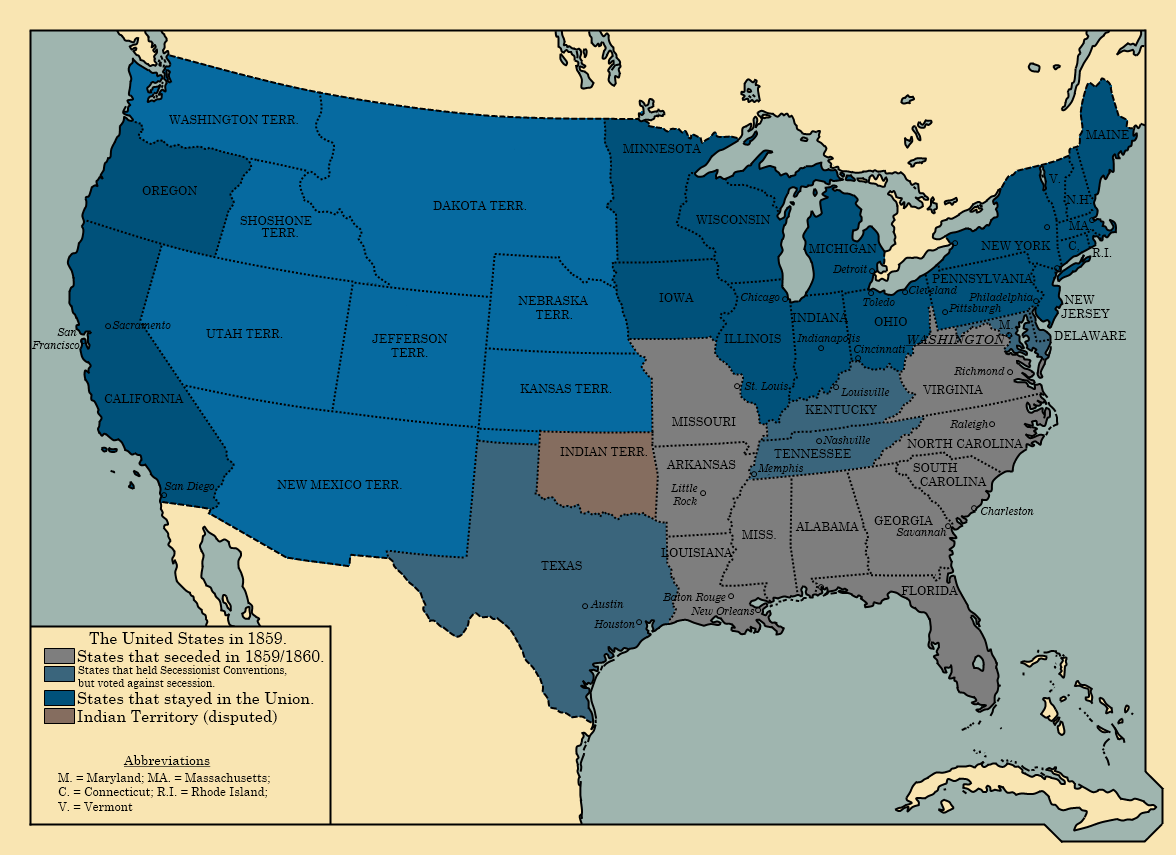

"As soon as the new Congress had entered session, Banks put his "New West" bill, now revised as the Territorial Reorganisation bill, forth to Congress for debate. The new act originally contained a provision that would establish popular sovereignty in New Mexico, but this was struck out when news of the new congressional majorities reached Banks. The provision was replaced by one formally recognising the Territory of Jefferson, which had been set up in the foothills of the Rockies, on land controlled by five different territories, a few weeks prior. A new Territory of Dakota would also be created, covering both the unorganised land left over from Minnesota and land to its west, across the Mississippi. The Territory of Shoshone would be established in the Snake River valley, and Nebraska and Kansas would both lose major land in their west in preparation for statehood.

The bill was vehemently opposed by literally every Southerner in Congress, who felt that their interests were being sufficiently protected by the Kansas-Nebraska Act. The Republicans, however, were almost entirely in favour of it, and since they had a majority in both House and Senate, the vote went in favour. President Fremont signed the bill into law, and on April 14, 1859, the Territorial Reorganisation Act was added into United States legal history."

***

From "To Live and Die in Dixie" by Willie Pearson

Duke University Press, 1946

"The signing of the Territorial Reorganisation Act caused great fury in the South, not only because the compromises of 1850 and 1854 had both been thrown onto the ash heap of history, but also because this was the first time that a major bill had passed into law with every single Southern congressman voting against. The general feeling was one of political castration, and the idea of secession found more and more adherents across the South…"

[1] Pierce did indeed go to Europe with his wife after being humiliated at the polls (or rather at the DNC). He didn't return to Washington until 1859.

[2] California.

[3] Walker's general Charles Frederic Henningsen razed Granada to the ground before leaving, IOTL and ITTL alike.

[4] In May of 1856, Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts gave a speech to Congress, strongly criticising the Southern Congressmen in general and Senators Andrew Butler and Stephen Douglas, the principal authors of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, in particular, for their part in triggering the Bleeding Kansas. He referred to Butler as a pimp and an adulterer, reportedly mocking his methods of speech (Butler was suffering from a stroke at the time). This enraged Representative Preston Brooks, a nephew of Butler, so much that he severely flogged Sumner with his cane in the Senate chamber two days later. Sumner suffered massive head trauma, and was almost killed. South Carolinians were enthusiastic, sending Brooks new canes (one was gold-tipped) and praising him in newspaper editorials, but Northerners were enraged, and turned Sumner into a martyr, furthering the strong divides over slavery.

[5] I'm not counting Sumner's seat, which was vacant as Sumner was still rehabilitating from his head injuries at the time.

[6] Already the elections of 1856 cost the Democrats their control of the General Assembly, as Buchanan's speech in Springfield (which, by the way, consisted mainly of stressing the right of popular sovereignty) caused him to lose significant popularity in the state, whereas Lincoln's response, a flaming speech about the right to freedom for all which is considered one of his best ITTL, made significant progress toward the Republicans gaining the state.