The Last Years of Alexander the Great Part 1

"What an excellent horse do they lose, for want of address and boldness to manage him!"

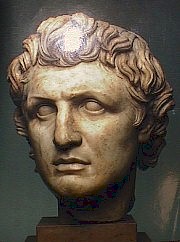

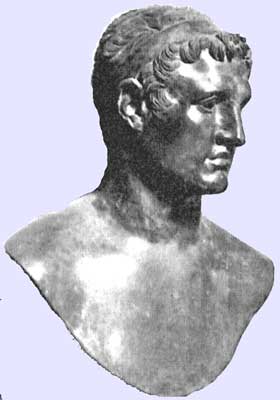

At the start of June in the year 323BCE, the generals and satraps of Alexander’s Empire were confronted with the very real possibility that Alexander the Great was not long for the world. He had fallen into a severe and probably paralytic fever. He was unable to speak, and could barely move without extreme pain. There were fears that he had been poisoned, though others blamed high alcohol consumption. But all of this was laid to rest, as on the 9th of June Alexander’s conditions showed signs of improvement. Whilst movement was still painful for him, his power of speech began to return, and it was clear that he would at least partially recover. By the 15th he was able to walk unaided, and within another week he was able to converse as normal. But the unknown ailment that had afflicted him had left its mark, Alexander could not now perform anything physically taxing without at least some pain and weakness.

This had a profound effect upon his psychology, and left him a noticeably quieter man than before. Later ages would attribute this quote to him in earlier times, “It is only during sex and sleep that I am reminded that I am mortal.” Now he knew for certain that he was mortal. Though some commentators and historians make more of it than is necessary, he had struggled his whole life with the legacy of his father Phillip II. Despite all his conquests, all his victories, and the vast and wealthy empire now under his control, he now felt that he had been pulled down to the same category as his father; afflicted physically. He never shook off the thought that the Gods’ disfavour had been made manifest in his condition.

The most immediate and marked effect this had were the precautions he made with regards to his son, Alexander IV. He realised that the child would be made extremely vulnerable in the event of his early death. He therefore had marked out Perdiccas to be the child’s guardian in the event of his death, whilst assembling the most trusted of his bodyguard to guard his son. It has been rumoured that the Magi of Persia were contacted as potential safeguards as well, though no historical source has ever been found to confirm this. What is certainly true is that the Persian aristocracy placed as much hope in Alexander IV as his own father.

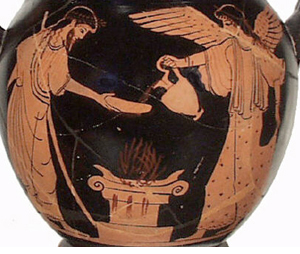

At this stage, Alexander was not finding the territories that he had taken from the Achaemenid Empire hard to police, but he was having extreme difficulty with the Hellenic heartlands. He had never fully trusted most of the Hellenic cities during his Asian campaign, and they had made every effort to thwart Macedonian control. This wave of anti-Macedonian feeling came to a head in the spring of 322BCE, when the Athenian orator Demosthenes led a co-ordinated movement to fire up as many poleis as possible against the Macedonian regime. Alexander’s mother, Olympias, was effectively the satrap of Macedon, and thus she was the one who took control of the situation. She forced the Athenians to arrest the anti-Macedonian ringleaders in Attika, and to arrest on sight anti-Macedonians from other cities. However, rather than be arrested, Demosthenes committed suicide, thus creating both a matyr and a catalyst for the new panhellenic movement that was being born.

This was of great concern to Alexander, who had used the rhetoric of panhellenism to justify and invigorate his campaign in Asia, and thus to legitimise his position among the Hellenic elements of his population. However, beginning in late 322BCE, communicating with Macedon became extremely difficult, and it is clear that Olympias was acting more like a client-queen than a satrap. The dangers of the transition from satrap to client-king was one that would haunt the Argead Empire for its whole span. This would have been less dangerous at the time had Athens not successfully revolted from Macedonian control, along with Achaea. By 320BCE, these would be joined by the majority of the Peloponnesians and the island of Euboea. If the movement spilled over to the islands of the Aegean, it would threaten Argead control over the coast of Anatolia, and from there the revolts might further catalyse.

Alexander made up his mind by Feburary of 321BCE. All of his close circle were against the idea, but the majesty of the King of Kings was enough to prevail. And thus he decided to conquer Arabia. This was not an unknown area or culture to him, especially with the small kingdom of Nabataea nestled closely to Egypt’s eastern border. The south of Arabia was at this time well settled, and rich from the trade in Frankincense. He moved from Babylon, the major capital of his Empire, to Egypt over a few months, taking his time in order to be able to make an impression on the local populations and also to fully assemble the logistics required for a large expedition. In the mean time, Antipater had been sent to the city of Alexandria on the Indus, where the Indus fleet would be awaiting him. The plan was for a pincer movement across the inhabited areas of Arabia. The obvious weakness of this strategy was that communication between the two armies would be almost impossible until they drew relatively near, or would have to be done via ships sailing along a hostile coast.

This coin was minted in 320BCE, and was part of a huge amount of currency minted in order to fund equipping and paying the vast army being assembled.

The Expedition Assembles

Before he left Babylon, Alexander had divided the Macedonian veterans that had remained in Babylonia between himself and Antipater. Skilled leaders such as Perdiccas and Ptolemy were divided between each army as well. Each army would be expected to call on contingents from various Macedonian garrisons and cities, but numbers would be made up with satrapal resources as well. This was hampered by the rebellion of those Saka tribes nominally under the authority of Alexander, Armenia, and parts of Arachosia that occured in the early part of 320BCE. But Alexander had access to Macedonian phalangites, some Macedonian heavy cavalry, and all of the inherited forces from the Achaemenid Empire. This might strike modern readers as strange, but it was general practice in the Near East that when a state was conquered by another, the conqueror would inherit the army of the recently conquered. So ancient Assyria acquired much of its manpower, and thus the brief Babylonian Empire, and the Achaemenids after them. Indeed, some of the forces available to Alexander were descended from brigades originally created in the 9th Century BCE by the Egyptians and Assyrians.

Those troops used to desert conditions were particularly highly prized by Alexander, and thus his force included Libyans, Nubians, Numidians, Egyptians, Medes, and even some Arab populations under his suzerainty. But the core of his forces remained Macedonian phalangites, supplemented by some Iranians, Chaldeans and Aramaics who had been trained as Phalangites. Their numbers were not great, as it would take many more years before the Argead Empire had access to large numbers of professional non-Macedonian phalangites, but it was a sign of developments to come.

The total of Alexander’s force is hard to judge, as it is difficult to trust any of the few extant biographical sources for Alexander with regards to numbers. But for certain it numbered in the tens of thousands. Obviously an army of this size needs feeding and watering, and fortunately Egypt proved an ideal base for exactly that; its huge agricultural produce was of extraordinary value, and would become even more so with the eventual rise of great megapoleis like Philloupolis, Alexandria in Arabia, Aleppo, Damascus, and some Egyptian grain cornels have been discovered in broken amphorae on the site of Alexandria on the Indus. Right now, its task was to feed and water the Royal Army of Alexander, a task it leaped to with what might seem surprising enthusiasm. A more difficult task was the transport of the army, as whilst there was something of a Red Sea fleet it was not in sufficient numbers to be able to transport a force of this size all at once. It seems that Alexander ordered the construction of purpose-built transports, especially ones capable of carrying horses easily, and rather than take the long and parched desert road overland he elected to ferry the army across to the north-west of Yemen in a series of trips. An advance force was sent to the oasis at Lathrippa in the September of 320BCE, and by October the first major force headed by Perdiccas was on its way.

The Vergina Sun, symbol of the King of Macedon and what would also become the symbol of the Argead Emperor.

"What an excellent horse do they lose, for want of address and boldness to manage him!"

At the start of June in the year 323BCE, the generals and satraps of Alexander’s Empire were confronted with the very real possibility that Alexander the Great was not long for the world. He had fallen into a severe and probably paralytic fever. He was unable to speak, and could barely move without extreme pain. There were fears that he had been poisoned, though others blamed high alcohol consumption. But all of this was laid to rest, as on the 9th of June Alexander’s conditions showed signs of improvement. Whilst movement was still painful for him, his power of speech began to return, and it was clear that he would at least partially recover. By the 15th he was able to walk unaided, and within another week he was able to converse as normal. But the unknown ailment that had afflicted him had left its mark, Alexander could not now perform anything physically taxing without at least some pain and weakness.

This had a profound effect upon his psychology, and left him a noticeably quieter man than before. Later ages would attribute this quote to him in earlier times, “It is only during sex and sleep that I am reminded that I am mortal.” Now he knew for certain that he was mortal. Though some commentators and historians make more of it than is necessary, he had struggled his whole life with the legacy of his father Phillip II. Despite all his conquests, all his victories, and the vast and wealthy empire now under his control, he now felt that he had been pulled down to the same category as his father; afflicted physically. He never shook off the thought that the Gods’ disfavour had been made manifest in his condition.

The most immediate and marked effect this had were the precautions he made with regards to his son, Alexander IV. He realised that the child would be made extremely vulnerable in the event of his early death. He therefore had marked out Perdiccas to be the child’s guardian in the event of his death, whilst assembling the most trusted of his bodyguard to guard his son. It has been rumoured that the Magi of Persia were contacted as potential safeguards as well, though no historical source has ever been found to confirm this. What is certainly true is that the Persian aristocracy placed as much hope in Alexander IV as his own father.

At this stage, Alexander was not finding the territories that he had taken from the Achaemenid Empire hard to police, but he was having extreme difficulty with the Hellenic heartlands. He had never fully trusted most of the Hellenic cities during his Asian campaign, and they had made every effort to thwart Macedonian control. This wave of anti-Macedonian feeling came to a head in the spring of 322BCE, when the Athenian orator Demosthenes led a co-ordinated movement to fire up as many poleis as possible against the Macedonian regime. Alexander’s mother, Olympias, was effectively the satrap of Macedon, and thus she was the one who took control of the situation. She forced the Athenians to arrest the anti-Macedonian ringleaders in Attika, and to arrest on sight anti-Macedonians from other cities. However, rather than be arrested, Demosthenes committed suicide, thus creating both a matyr and a catalyst for the new panhellenic movement that was being born.

This was of great concern to Alexander, who had used the rhetoric of panhellenism to justify and invigorate his campaign in Asia, and thus to legitimise his position among the Hellenic elements of his population. However, beginning in late 322BCE, communicating with Macedon became extremely difficult, and it is clear that Olympias was acting more like a client-queen than a satrap. The dangers of the transition from satrap to client-king was one that would haunt the Argead Empire for its whole span. This would have been less dangerous at the time had Athens not successfully revolted from Macedonian control, along with Achaea. By 320BCE, these would be joined by the majority of the Peloponnesians and the island of Euboea. If the movement spilled over to the islands of the Aegean, it would threaten Argead control over the coast of Anatolia, and from there the revolts might further catalyse.

Alexander made up his mind by Feburary of 321BCE. All of his close circle were against the idea, but the majesty of the King of Kings was enough to prevail. And thus he decided to conquer Arabia. This was not an unknown area or culture to him, especially with the small kingdom of Nabataea nestled closely to Egypt’s eastern border. The south of Arabia was at this time well settled, and rich from the trade in Frankincense. He moved from Babylon, the major capital of his Empire, to Egypt over a few months, taking his time in order to be able to make an impression on the local populations and also to fully assemble the logistics required for a large expedition. In the mean time, Antipater had been sent to the city of Alexandria on the Indus, where the Indus fleet would be awaiting him. The plan was for a pincer movement across the inhabited areas of Arabia. The obvious weakness of this strategy was that communication between the two armies would be almost impossible until they drew relatively near, or would have to be done via ships sailing along a hostile coast.

This coin was minted in 320BCE, and was part of a huge amount of currency minted in order to fund equipping and paying the vast army being assembled.

The Expedition Assembles

Before he left Babylon, Alexander had divided the Macedonian veterans that had remained in Babylonia between himself and Antipater. Skilled leaders such as Perdiccas and Ptolemy were divided between each army as well. Each army would be expected to call on contingents from various Macedonian garrisons and cities, but numbers would be made up with satrapal resources as well. This was hampered by the rebellion of those Saka tribes nominally under the authority of Alexander, Armenia, and parts of Arachosia that occured in the early part of 320BCE. But Alexander had access to Macedonian phalangites, some Macedonian heavy cavalry, and all of the inherited forces from the Achaemenid Empire. This might strike modern readers as strange, but it was general practice in the Near East that when a state was conquered by another, the conqueror would inherit the army of the recently conquered. So ancient Assyria acquired much of its manpower, and thus the brief Babylonian Empire, and the Achaemenids after them. Indeed, some of the forces available to Alexander were descended from brigades originally created in the 9th Century BCE by the Egyptians and Assyrians.

Those troops used to desert conditions were particularly highly prized by Alexander, and thus his force included Libyans, Nubians, Numidians, Egyptians, Medes, and even some Arab populations under his suzerainty. But the core of his forces remained Macedonian phalangites, supplemented by some Iranians, Chaldeans and Aramaics who had been trained as Phalangites. Their numbers were not great, as it would take many more years before the Argead Empire had access to large numbers of professional non-Macedonian phalangites, but it was a sign of developments to come.

The total of Alexander’s force is hard to judge, as it is difficult to trust any of the few extant biographical sources for Alexander with regards to numbers. But for certain it numbered in the tens of thousands. Obviously an army of this size needs feeding and watering, and fortunately Egypt proved an ideal base for exactly that; its huge agricultural produce was of extraordinary value, and would become even more so with the eventual rise of great megapoleis like Philloupolis, Alexandria in Arabia, Aleppo, Damascus, and some Egyptian grain cornels have been discovered in broken amphorae on the site of Alexandria on the Indus. Right now, its task was to feed and water the Royal Army of Alexander, a task it leaped to with what might seem surprising enthusiasm. A more difficult task was the transport of the army, as whilst there was something of a Red Sea fleet it was not in sufficient numbers to be able to transport a force of this size all at once. It seems that Alexander ordered the construction of purpose-built transports, especially ones capable of carrying horses easily, and rather than take the long and parched desert road overland he elected to ferry the army across to the north-west of Yemen in a series of trips. An advance force was sent to the oasis at Lathrippa in the September of 320BCE, and by October the first major force headed by Perdiccas was on its way.

The Vergina Sun, symbol of the King of Macedon and what would also become the symbol of the Argead Emperor.

Last edited: