Official Name: Imperio Unido de las Españas (in Spanish), Império Unido das Espanhas (in Portuguese), United Empire of the Spains (in English)

Capital: Madrid

Other important cities: Lisbon, Barcelona, La Habana, Manila

Demonym: Spanish

Government: Unitary parliamentary constitutional monarchy

- King: Leopoldo I

- Prime Minister: Francisco Silvela (Partido Liberal-Conservador) (since 1898)

- Deputy Prime Minister: Francisco Maura

- Legislature: General Courts

- Upper House: Senado

- Lower House: Congreso de los Diputados

Languages:

- Official: Spanish, Portuguese

- Other: Arabic, Catalan, Cebuano, Euskera, Galician, Tagalog, Winaray

Formation:

- Visigothic Kingdom of Toledo: 507

- Muslim Invasion: 711

- Dynastic union between Castile and Aragon: 1479

- De facto union between Castile and Aragon: 1516

- First Unification between Castile, Aragon and Portugal: 1581

- Portuguese Independence: 1640

- De jure union between Castile and Aragon: 1715

- Nation State of Spain: 1812

- Current democracy: 1869

- Restoration of Rosellón and the Oranesado: 1870

- Second Unification between Spain and Portugal: 1892

Population: 45,027,956

Area:

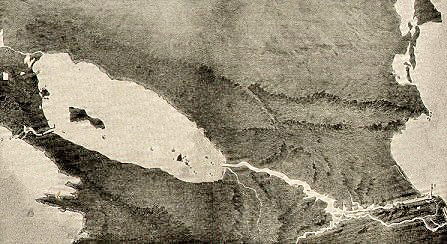

- Total: 2,866,763 km2 (Europe: 599,702; America: 118,988; Africa: 1,774,412.5; Asia: 373,660.5)

- Water: 0.88 %

Density: 15.707 inhabitants/km2

Currency: Peseta

While it is true that it is not as powerful as the Spanish Empire was during Philip II of Spain and I of Portugal's reign, the United Empire of the Spains can certainly say that they are, at least, half the way towards regaining part of that power. Even if they still are under the shadow of other powerful nations, such as the United Kingdom or Germany, any Spaniard can be sure that it will not be long until their homeland becomes a power of its own in the international scene.

Governance

Branches of government

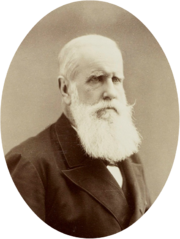

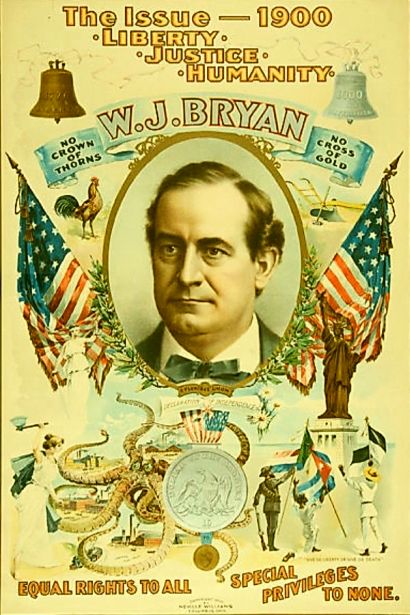

Spain is a constitutional monarchy, with a hereditary monarch. The current monarch is sixty-five-year-old Emperor Leopoldo I, from the House of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen, married to Empress Antonia of Braganza, who was the one that inherited the Portuguese Crown, allowing the unification of Spain and Portugal.

The legislative branch is formed by the

Cortes Generales, made up of the

Congreso de los Diputados, formed by 450 deputies representing the different provinces of the Empire in terms of proportionality of numbers, and the

Senado, formed by 2 senators elected per province by popular vote and 1 per Foral Region by appointment, thus numbering around 150 senators.

The executive branch is formed by the Consejo de Ministros de España presided by the Presidente (the equivalent to the Prime Minister), who is formally nominated and appointed by the monarch and confirmed by Congress after legislative elections that, by law, take place on the first Sunday of April every three years. However,

de facto, the nominee is always the candidate presented by the party with the plurality of seats in the Congress.

The judicial branch is formed by an independent judicature whose members have to pass an exhaustive exam to demonstrate their ability to be impartial and apply the Civil and Penal Codes of Law.

Territorial Organization

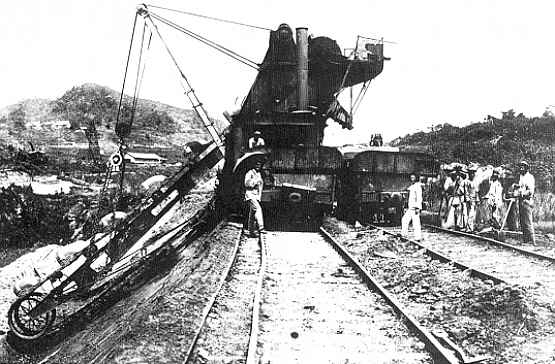

Spain's current territorial organization owes much to the Treaty of Baraguá that put an end to the Cuban Revolutionary War in 1873. This treaty conceded Cuba autonomy to deal with local matters, an event that had already been foreseen in the 1869 Constitution, but that had yet to be implemented due to the chaos of the war and the problems taking place at home. Upon expanding this autonomy to Puerto Rico, and later to the Philippines, the Spanish government realized that this could be also taken to the Metropoli, as it would reduce the pressure of the administrative tasks government had to handle.

The current system has the territories of the United Empire divided in four groups:

- Political Foral Regions: these are regions that have their own parliament and regional government. They are allowed to pass their own legislation and to decide on all local matters, but the central government in Madrid supersedes them, and may overturn any legislation that oversteps their boundaries. Currently, Cuba, Portuguese India, Habagatan, Hilaga, Kabisayan and Puerto Rico are the only political foral regions, although it is expected that others may join in the future.

- Administrative Foral Regions: these regions have administrative autonomy to deal with local matters, such as tax collecting, the allocation of money towards local projects and other powers. Politically, they still depend on Madrid to determine legislation, although several of them might intend to take steps towards political autonomy. The sixteen metropolitan Foral Regions (Algarve, Andalucía, Aragón, Atlántico, Beja, Bética, Castilla La Nueva, Castilla La Vieja, Extremadura, Galicia, León, Levante, Lusitania and Vascongadas) and the Oranesado (in northern Africa) are at this level.

- Colonies: these territories are not developed enough to support a local, autonomous administration. Although there is a Governor that is allowed to make choices, and can decide what to do in emergency events, most things are left to the Ministerio de Ultramar in Madrid to decide. Heavy military presence in these regions ensures the protection of both the settlers and the locals who have sworn allegiance to the Spanish Crown. Spain's colonies are Angola (south-western Africa), Guinea (central Africa), Moçambique (south-eastern Africa) and Río de Oro (western Africa).

- Protectorates: although they are actually not part of the Empire, they can be treated, more or less, as this. The protectorates are independent nations that, nonetheless, have accepted, voluntarily or by force, Spain's guidance in international and commercial affairs, as Spain is the only nation they can – or will – make deals with. Spanish officials are quite influential in these nations' governments, trying to lead them towards taking actions that will benefit Spain, and Spanish businessmen are allowed to establish factories or make trading deals with the locals at low tariffs. The main protectorates are the Dominican Republic, Morocco and Siam, the former of which is slated to offer its citizens the chance to vote for reunification with Spain in 1903.

International Relations

Spain's main ally in the diplomatic sphere is, undoubtedly, the German Empire. Forged in the fires of the Hohenzollerns' War, and kept alive thanks to the many diplomatic, cultural, military and trading exchanges, many a Spaniard looks to Germany as a friend, perhaps even a sibling, in the trying times that currently exist. This, coupled with the familial link between Emperors Leopoldo of Spain and Friedrich Wilhelm of Germany, has all but ensured that the relationship will remain strong, especially after Germany began its political transformation that liberalized the government. In the case either were to get involved in a war, it is clearly assumed that the other would soon follow.

Another ally of Spain is the Kingdom of Italy. Old grudges put aside with the passage of time, Italy has indeed welcomed Spain as a friend. The death of King Umberto's sister in the event that sparked the Portuguese Civil War had easily cemented this alliance, for it had brought with it the unification of Spain and Italy's support in the Santiago Conference where the United Kingdom and France finally accepted the

fait accompli of the unification.

Peru and Bolivia are Spain's best friends in America, the relationship going strong since Spain's aid during the Second Pacific War. The extent of Spanish investment in the two nations has only grown since then, and it has been the pleasure of many to visit each nation, with several people actually encountering relatives that either went to the Americas or returned to the Motherland for one reason or another.

Japan, Spain's main partner in Asia, can count itself to be glad of such friendship, for all it has done is to help reinforce their position in the region thanks to the trade with both them and Germany. Several Spaniards, mainly from those that reside in either the Philippines, Macao or the Spanish embassy in Tokyo, have actually adopted some of Japan's cultural mores, and in turn a few Japanese have acquired not a few Spanish customs.

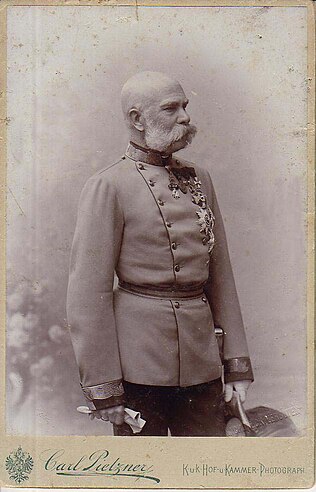

Meanwhile, Austria-Hungary is, at most, a fair-weather ally to Spain. Aging Emperor-King Franz-Joseph is not exactly glad of having Spain as a member of the alliance group he has formed with Germany, not to mention the influence they have with the opposition to his “God-given” right to rule. Still, he is capable of standing them, if only because of those nifty submarines built in Spanish drydocks and sold to the

k. u. k. Kriegsmarine.

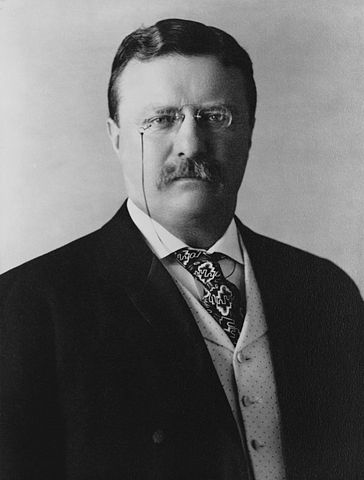

Back to the Americas, the United States is keeping a cold relation with the Empire, the warm feelings from directly after La Gloriosa have been disappearing as Spanish control over Cuba and Puerto Rico strengthened, not to mention Spain's increasing influence over Peru, Bolivia, Nicaragua and Santo Domingo. Many of the most hawkish members of Congress and the Senate are pushing for a war against Spain, to “liberate” Cuba, Puerto Rico and Santo Domingo from Spanish control and enforce the Monroe Doctrine, cries that are starting to be heard by the President and the government.

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland has yet to forget the slight to their honor that was the Santiago Conference, as their “sensible suggestions” were rejected out of hand by the Spanish government. After all, what they want is to preserve the balance of power in Europe! However, when they are reminded that they were, in essence, the catalysts for the Portuguese Civil War, they remain strangely quiet. Any mention of the British within the Algarve, Beja or Lusitania is bound to extract an angry torrent of insults towards Perfidious Albion from any group of people.

Finally, just like Germany is Spain's greatest ally, France is Spain's greatest enemy. Still bitter over the many losses caused by Spain's mere existence – the Roussillon, the Oranesado, Alsace-Lorraine, Morocco, Corsica... – many of France's military plans have as its goal the destruction of Spain's military capabilities before turning to Germany, and Spain's support for the Jewish people that have left France in the wake of anti-Semitic attacks after the Dreyfus Affair became known have only increased these ill feelings towards their southern neighbors.

Armed Forces

The Spanish Royal Armed Forces, whose Commander-in-chief is Emperor Leopoldo I, may be divided in three branches: the Army, the Navy, and the Air Force.

The Army

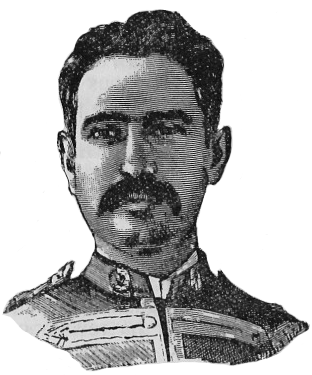

The Army is the biggest group of the SRAF, mostly formed by conscripts around a medium-sized core of professionals. Conscription requires all Spanish males to spend a whole year, training in a military camp, upon the age of 18, with only few exceptions, such as the sons of widows or those who have a disability that prevents them from fulfilling the military service. This training consists of learning how to use weaponry from handguns to rifles, and, depending on which part of the Army they train with, specific tactics or special training: while Infantry learns how to make use of the terrain to better attack the enemy, Cavalry works on ambushes and fast attacks and Artillery practices shooting at far-away targets. At the end of the twelve months, they are given a certificate that states their completion of their military period and reminded that, in case of war, they might be required to join the army.

Those soldiers that desire so may join the Army full-time, becoming professional soldiers. This option tends to be offered to any conscript that proves to be good enough at the task, but they will accept anyone capable of doing a good job. Upon joining as professionals, they are given greater training than what they had as conscripts. Any that shows brilliance in the use and development of tactics and strategy may be invited to one of the four

Escuelas de Oficiales del Ejército that exist in Spain (La Habana, Manila, Zaragoza and Sevilla), while those that prove to be excellent at the task are encouraged to apply for the

Tercios Especiales, the elite unit of the army trained in asymmetrical warfare, infiltration and other things that are not easy to carry out with a normal-sized army.

Currently, the Spanish Royal Army's main service weapon is a RESA R-7 rifle, a bolt-action rifle with an 8 round stripper clip in internal magazine that uses 7x57mm smokeless gunpowder rounds, fired at a speed of approximately 815 m/s, with an effective range of 460 m when using iron sights. Some units, like the

Tercios, use specially modified rifles that have a greater range, and others (such as the

Cazadores regiment in the Cavalry) use a carbine that descends from the model designed by the already deceased Cosme García Sáez back in the 1870s. Another development that has spread out is the use of the RESA A-2 machine-gun, a weapon based on the designs for the Maxim gun, but well improved, capable of firing about 500 rounds per minute, with an effective firing range of 1.8 km.

Meanwhile, the Artillery divisions carry several types of weapons, the most powerful one being the CESA CC-99 cannon, a regimental artillery field gun capable of firing 80x350 mm shells (weighing between 5.5 and 7.5 kg) at ranges surpassing 7 kilometers. Other weapons include the CO-98, a heavy howitzer capable of shooting 50 kg shells with an effective fire range of 5.2 kilometers; the CI-97, a light gun used to support infantry; and the CM-99, a mortar that can be used to fire on entrenched positions.

The Navy

Before the Hohenzollerns' War happened, the Spanish Navy was the fourth most powerful in the world. Thirty years later, the efforts carried out by the drydocks and naval engineers have all but ensured that position remains firmly in their power, perhaps even nearly tying France for the third place.

One of the best additions to the Navy has been the battleship, which has contributed to increasing the power the Navy has, and allowing it to project it anywhere in the world where Spain is involved in a war. The greatest among them is the Spanish Navy's flagship, the

Hispania, and the current

Hispania-class battleship has five completed ships (

Hispania and

Lusitania in the Home Navy,

Juana and

San Juan Bautista in the Caribbean and

Filipina in the Philippines) and two more, which are to be finished in 1901 (tentatively named

Don Pelayo and

Rey Leopoldo, the former of which will join the growing African Fleet in Luanda). There are two other battleship classes in the Spanish Navy: the

Tenerife-class, with five ships (

Tenerife,

Gran Canaria,

Lanzarote,

Fuerteventura and

Gomera), and the

Emperador Carlos I-class with three ships (

Emperador Carlos I,

Rey Felipe II and

Rey Fernando V).

The next ships in size in the navy are the cruisers, of which there are two kinds, armored and protected.

- The best armored cruisers at this time are the Blas de Lezo-class, which has five ships: Blas de Lezo, Méndez Núñez, Francisco Gravina, Manuel Pessanha and Vasco da Gama. There are two other armored cruiser classes in the Navy: the Don Henrique-class, with four ships, and the Lepanto-class, with five ships.

- As for protected cruisers, the main class is the Isla de Cuba-class, that has four ships: Isla de Cuba, Isla de Puerto Rico, Isla de Luzón and Isla de Mindanao. The previous classes are the Cartagonova-class, with three ships, and the Atlántico-class, with three more ships.

Then go the destroyers. An invention developed by Spanish admiral Fernando Villaamil, then an officer in the Ministry of Navy, in response to the torpedo boats other nations were starting to build, it has proven to be a very welcome addition to the navy. The first ship of this class, the

Destructor (after which all ships of this type are called), was built in 1888 in the El Ferrol shipyards. It was after this ship that many more were build. Currently, Spain can boast of having sixteen destroyers: five

Destructor-class, six

Valiente-class and five

Churruca-class destroyers.

The patrol gunboats number twenty-five in the Spanish Navy: ten from the

Rayo-class, eight from the

Neptuno-class and, finally, seven from the

Ebro-class.

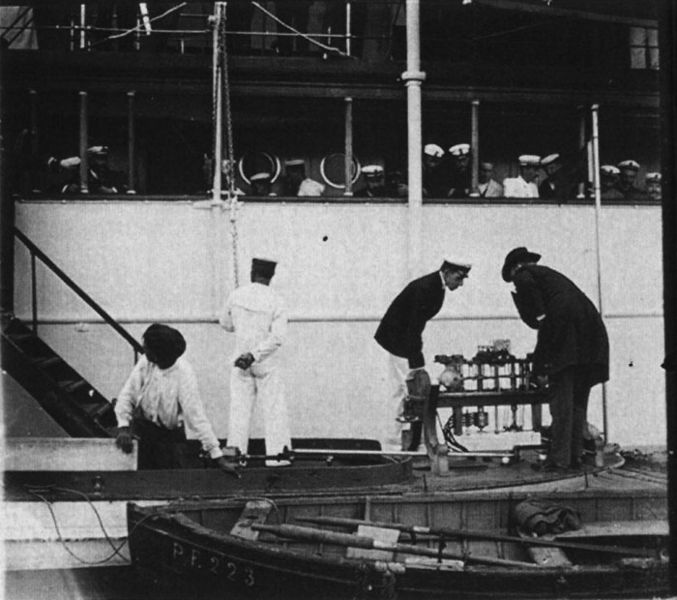

Finally, the submarines. The advantage of having the best submarine engineers in the world, thanks to the efforts of the

Escuela de Ingenieros Navales, one of whose groups is fully dedicated to learning the workings of submarines and presenting new ideas for development of more submarines to add to the navy. Right now, twenty-seven submarine boats have joined the navy: the

Poseidón-class has seven submarines, the

Delfin-class nine, the

Peral-class nine and the

Tempestad-class has two. Several mini-submarines, of small size and tripulation, intended for use in shallow waters and patrols, have also been developed, forming part of the

Rana-class.

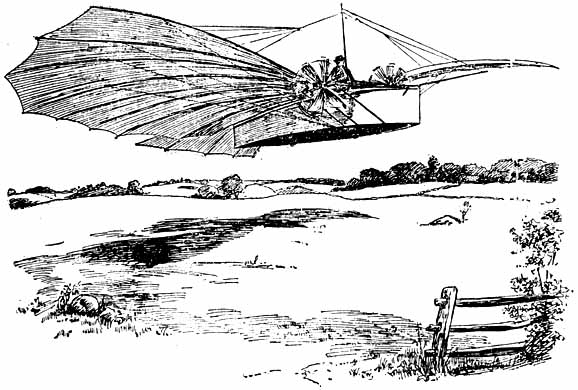

The Air Force

The newest of the Armed Forces, the Air Force is ground-based and their uses are limited, due to the fact that they are formed by globes that can only go with the wind. However, 1901 is to see an expansion of the navy thanks to the construction of a few zeppelins and dirigibles in a collaboration between Spanish and German industries: many have seen in the skies the weapon that can fully change the sign of how war is to be fought. The future flagship of the Air Force is the zeppelin

Iberia, which should take off on October 12th 1901.

Heavier-than-air flight remains a pipe dream for the moment, although, much like everywhere else in the world, engineers are working to develop this idea. However, they are not anywhere near to achieve it.

Culture

Literature

The resurgence of Spain as a world power has greatly increased people's moral and belief in their nation, and the unification with Portugal has also been welcomed with open arms by writers and poets. The changes in policy, the regeneration of the nation and the bright look towards the future have infused many a book.

Ramiro de Maeztu, a member of the group of writers that is being called the

Generación de la Regeneración and journalist for El País, has, after traveling for three years across Spanish Africa (Morocco, Río de Oro, Guinea, Angola and Moçambique) as part of his job, written a book called

Viajes de un Español por África. This book, telling much about the current status of the colonies and protectorates, has brought great interest for the Dark Continent in the Peninsula and the Caribbean, as they learn about the customs of the native people, who Maeztu, although calling them out on some ideas, does praise them for the simple, communal lives they have, urging people to adopt at least parts of these ideals to improve the sense of community within Spain.

A new genre called

ficción científica, based on the writings of Jules Verne and a young Hugh Shelley, has also spread in Spain, divided in two currents:

brillante, that optimistically looks to the future and the changes it can bring, and

oscura, which believes that the unchecked progress of technology will, eventually, bring humanity down to war unless drastic changes take place. In the former group stands out

Los Cien Años de Marte, which tells the story of the one hundred years since the first Earth people (a motley of people from all nationalities) arrive to the Red Planet until they manage to become fully independent, the main group that leads the conquest of the stars.

A smaller genre is the genre of

ucronía, which some people use to say what could have happened if certain historical events had evolved in different ways. The two most sold books of this genre are

Cuatro Siglos de Buen Gobierno, which begins with the tale of Miguel de la Paz, a grandson of the Catholic Monarchs that could have joined the crowns of Castile, Aragon and Portugal but died at the age of two, and works out how a Spain fully united by a living Miguel de la Paz could have changed in the four posterior centuries; and

El Reino de la Cruz Blanca, which posits the idea that, had the French got wind of King Leopoldo's candidacy before the vote, Spain would have ended up having Amedeo di Savoia as the new King of Spain, and, while it does not do as well as in reality (there is no war with France, the Carlist and Cuban Wars last longer) it manages to survive more or less intact, even repelling an unwarranted attack by the United States into Cuba, sparking a war between several European nations and the United States of America, an event that is to take place in the unpublished sequel to that book.

Poetry has also taken off among the

Generación de la Regeneración, with its greatest exponents being the Machado twins (Roberto and Antonio), the former becoming known for his uplifting writing about Spain, and the latter for his work in social realism, particularly talking about the factory workers that toil daily, sometimes for a pittance, in the nation's factories, and trying to bring change to their situations.

The multitude of languages spoken in Spain has also sparked similar movements for each language. For example, famed Filipino politician and writer José Rizal has popularized Tagalog literature in the Philippines, thanks to, among other works,

Noli Me Tangere, that relates the effects of the Spanish government's reforms in the 1870s and the hard opposition of the oligarchs, represented in the story by fanatic Fray Dámaso, lustful Fray Salví and greedy

Peninsular Linares, all of which conspire to ruin protagonist Juan Ibarra's life and prevent him from both gaining justice for his father's death (indirectly caused by Fray Dámaso) and marrying his betrothed, María Clara de los Santos (who Salví lusts over and Linares wants to marry in order to be able to take over María Clara's inheritance), but the aid of Elías, another

Peninsular married to a Filipina, Ibarra manages to ruin their plans and bring about the successful construction of a school that had once been planned by his father (a symbol of Spain's reforms, which had started in the schools), which becomes inaugurated on the same day he finally marries his beloved.

Kinematography

The art of kinematography, invented barely a decade ago, has started to gain some influence in the Spanish cultural sphere. So far, Madrid, Barcelona, Lisbon, Santiago de Cuba and Manila are the only places where studios have started to appear, what with their importance to the national economy, but they are nonetheless starting to make good films that last for a few minutes – so far, the longest, a comic encounter between two circus clowns, barely reaches ten minutes – for the enjoyment of the people that can afford to pay for the entrance. The foremost Spanish film directors are Eduardo Jimeno and Víctor Aurelio Chomón.

Sports

Many are the sports enjoyed by the Spanish people in this time and age. One of the most popular sports is pelota, in which two people or couples must hit a ball against a wall in such a way that the other cannot do the same before it bounces twice on the ground. Pelota games are so popular that even the Royal Family attends games when they are held in Madrid or when they travel somewhere where a game is taking place. In the most recent Olympic Games, held in Paris, a pelota tourney was held, and Spain won the gold medal, to the anger of the French spectators that expected an easy victory for their country's pelotari.

Many sports also practiced in the Olympic Games are spreading, as well. Athletics, at least in part, has been a part of the teachings in many schools, following the mens sana in corpore sano motto for teaching, and swimming was quite common in cities near the sea or with deep enough lakes and rivers.

Another sport that has also spread out to Spain is football, although no one knows it by that name at all. If you go to the Spanish-speaking regions, they will tell you it is called balompié, and in Anglo-phobic Algarve, Beja and Lusitania, it has become quite popular as balompé. Teams have appeared in the main cities of Spain, particularly in the industrial regions, but by the end of the century every capital of province has at least one team. The first team that was officially constituted as a football team was the Recreativo de Huelva in 1878, the first recorded game between teams of different cities was a Madrid – Getafe in 1880, and a game was celebrated between Spanish and Portuguese players in 1892, as part of the celebrations for the Unification. The Federación Española de Balompié was founded in 1895, organizing the first tournament between teams in 1896, named Copa de España, a competition won by the Cañoneros de Getafe in its first edition. The Caribbean and the Philippines are also seeing the slow spread of the sport thanks to the travels of many Spaniards that wish to play their games even there, with the Habaneros de La Habana being established in 1887 and the Indios de Manila in 1888, with each island or archipelago starting their own internal competitions. There are talks of starting a tournament that teams from all of the Empire of the Spains can join in, with tentative marking of 1902 for such an event.