This is from December 1941. It makes mention of Cecil Brown reporting from the attack on HMS Repulse. One way of confirming messages are received could come on a 0110Z broadcast from JLG4 15105 Kc or JZJ 11800 Kc Tokyo. This is found under Short-Wave Program Listings for an English speaking audience. You can follow the war from home.Yes, but. Shortwave is affected in hard-to-understand ways by environmental and atmospheric factors, and even geology. A sender has no way to know for certain if their sent-once message will have reached a particular distant listener. Reliable shortwave communication involves sending repeatedly, at different times of day, preferably from multiple transmitting antennas; and the other end having many listening stations at distributed locations with complex antenna arrays, all noting what they've received and collating a combined transcript.

Shortwave antennas must be raised above their surroundings (vegetative, buildings and the terrain) to have much range. Historically one of the hardest aspects of operating a clandestine shortwave system has been concealing the antenna. A "20 meter band" vertical array needs a radiator of about six and a half meters, and multiple other elements. A horizontal dipole's main element is about ten meters long, and...ideally...raised above its surroundings by twenty meters or so.

A favorite competitive shortwave hobbyist activity is DXing...listening for, and keeping records of, distant senders you've heard. If there was more consistency to shortwave as a communications method, shortwave reception would be a simple matter of power, antenna configuration and a few other factors...but it's not so simple.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Malaya What If

- Thread starter Fatboy Coxy

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 264 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

MWI 41120514d Royal Navy Eastern Fleet OOB MWI 41120618 Shuffling The Pack MWI 41120617 The Ongoing Development Of The Airfields MWI 41120617a RAF Far East Command MWI 41120618 Rommel Retreats To The Gazala Line MWI 41120619 Kondo’s Dilemma MWI 41120620 Matador Is On MWI 41120702 The Race BeginsHow large is the transceiver? My guess is that 5W may beI know ham radio operators who use CW and get around the world and then some by CW, morse code, on just 5 watts.

How large is the transceiver? My guess is that 5W may be about 100 lbs?I know ham radio operators who use CW and get around the world and then some by CW, morse code, on just 5 watts.

It's a towed target for practice! The IJA mentions it as your Malayan Air component is delaying deployment of IJA air assets to the Makassar campaign. The IJN perforates the banner raised up!Hi Nevarinemex, I'm, with you on this one, the Kido Butai would only pass through the Makassar Straits after both Borneo and Celebes have been fully occupied, but I'm not sure why they have to come into the fight yet, if at all.

One of the ones that they used in Europe, other models were used in different places.How large is the transceiver? My guess is that 5W may be

How large is the transceiver? My guess is that 5W may be about 100 lbs?

Paraset radio

When you are doing something with CW and 5watts it doesn't take much, one of the ways they did this was to use crystals for the radio that plugged in individually for each unit so they would not compromise other units if they were captured. You might only have 4 or 5 crystals to use over different days or check ins with maybe a set to be used if you were captured to let them know because you are transmitting on a certain frequency you were done.

I was thinking along the lines of the size of the power generator for the set. It appears that the Paraset had upwards of six (6) input power taps on 50 cycles. However, the power supply requires a 50 cycle AC source. The indications are that its range was upwards of 850 miles. So Manado to Palau is doable.One of the ones that they used in Europe, other models were used in different places.

Paraset radio

When you are doing something with CW and 5watts it doesn't take much, one of the ways they did this was to use crystals for the radio that plugged in individually for each unit so they would not compromise other units if they were captured. You might only have 4 or 5 crystals to use over different days or check ins with maybe a set to be used if you were captured to let them know because you are transmitting on a certain frequency you were done.

The German 5W Sender CW looks like it had vibrator tubes. I don't know if that is accurate or not. If it was, then batteries, 6V or 12V might suffice.

I know ham radio operators who use CW and get around the world and then some by CW, morse code, on just 5 watts.

For shortwave, antenna optimization is an alternative to power. If you can build a good antenna up in the air...particularly a highly directional, high gain antenna...your set can be quite modest. But, usually clandestine radios had to use much less optimal antennas to avoid visual discovery.

Shortwave radio can be quite directional...or more precisely, it can have relatively sharply defined nulls in its transmission pattern...if a horizontal-type antenna with high gain is used. If a clandestine operator knew the exact compass direction to an enemy listening station, that clandestine operator could orient his/her antenna array, not so much for optimal signal strength toward his intended receiver, but instead for close-to-zero signal strength at the enemy listening station. But if the enemy may have multiple distributed listening stations, that option is unavailable. And signals do weird things sometimes, so what might be a null at the antenna might not be zero signal at long distance.

tell that someone is transmitting (...) from Java.

At long distances, it's not reliable to attempt to direction-find the source of a transmission. Shortwave signals can be reflected and deflected in curious ways by environmental conditions. Direction-finding at long range is guesswork. Aside from that, the reason that clandestine operators try to keep their messages as short as possible is that direction finding in the 1940s was a manual process, involving rotating a highly directional antenna to find the orientation where the received signal was minimized. Then the source...maybe if being received at long range, or very likely if at shorter range...was at ninety degrees to that null-axis. But that process took a bit of time. If the transmission was short enough, maybe there wouldn't be enough time to direction-find its source, and the clandestine operator would not be found out that time.

Last edited:

Part of the success of the British Huff-Duff system was that it was not manual. Using an oscilloscope and an array of antennas receiving from different angles, it was basically instantaneous. For quite some time the Germans Navy thought they were safe transmitting as they used a burst cypher system that kept messages to under a minute. But Huff Duff picked them up anyway.Aside from that, the reason that clandestine operators try to keep their messages as short as possible is that direction finding in the 1940s was a manual process, involving rotating a highly directional antenna to find the orientation where the received signal was minimized.

When you watch the old movies you might see someone cranking a generator by hand, and by generator it is the size of one that would be in your car. You are not running ac power it is DC power into the radios. The advantage of that is you don't have to lug heavy batteries around with you and can set up anywhere that is convenient.I was thinking along the lines of the size of the power generator for the set. It appears that the Paraset had upwards of six (6) input power taps on 50 cycles. However, the power supply requires a 50 cycle AC source. The indications are that its range was upwards of 850 miles. So Manado to Palau is doable.

The German 5W Sender CW looks like it had vibrator tubes. I don't know if that is accurate or not. If it was, then batteries, 6V or 12V might suffice.

Antenna can be a simple as using ladder line to make both the feed line and antenna itself. Using a antenna calculator on a 7mhz frequency you get 33 ft. for both legs of a dipole for a total length of around 66 ft for dipole with both legs and then how much you have for your feed line. Then have between 50 and a hundred feet of the actual feed line for a length around 150 feet length. All easily hidden in different parts.

MWI 41112312 The Gurun Line

Fatboy Coxy

Monthly Donor

1941, Sunday 23 November;

There had been plans for this, going back to when Lord Gort and Percival had first toured the country on their arrival in December 1940. The plans had taken on more detailed, with the arrival of the III Indian Corps commander, Godwin-Austen, who had increasingly pressed for such a defence. The Jitra line was good for a political statement of defending all of Malaya, but its defensive qualities were badly wanting. What was wanted was a solid backstop.

When they had discussed what units might be used for Operation Matador, it quickly became apparent that most of the Indian units were not sufficiently proficient for mobile operations, being only capable of fixed defensive roles. That meant only the Australians and a few supporting units could be the sword, while the Indian Army, in the main, would have to be the shield. The adoption of Matador, if it should happen, would give them a delaying action option, buying more time for the shield to prepare for what could become the ‘Battle for Malaya’. But whether Matador happened or not, the Indians would hold the Jitra Line, and now this one, with the Australians as the strategic reserve.

Frustratingly, little had been done other than planning and surveying, owing to Civil Government restrictions, but the passing of the Malaya War Act, had sweep them away, and before the end of September, the work had begun. The rail stations at Gurun, Bedong and back in Sungai Petani were all being enlarged with passing loops, and more sidings being added, with a number of magazines, bunkers, and widely spaced warehouses, located in rubber plantations nearby being built.

The Gurun line ran for twenty miles north easterly, from the coast just north of Kedah Peak to Perak Mountain. The first six and a half miles were behind a large drainage canal, with extensive padi fields north of it, and a metalled road running from Yan to the crossroads at the village of Chempedak, sitting behind it. Crossing the main road heading north, the line ran for another 3 miles easterly, again with padi in front, and the lateral road continuing behind. It then met the foothills of the Bintang mountain range, where jungle took over, and the road stopped.

Now the line became a series of outposts, centred on high points or across the trails to be found running through the jungle. Access to, and servicing these outposts was a major concern, and the ones close to Perak Mountain were served from the village of Jeniang, which was accessed by a small metalled road from Gurun, and had a well-defined trail heading north to the mountains. Behind the lines sat Kedah Peak, then extensive rubber plantations for about 5 miles, and then again, the jungle closed in.

Plantation trails were being improved, keeping the twists and turns, not allowing long straight stretches, making it more difficult to follow from the air, but as the work progressed further east, the move into jungle slowed this development. Among the plantations or in small clearings cut from the jungle, buildings or sheds were to be built, for housing men and supplies.

Further forward would come the gun pits, with 1-2 trees removed, sufficient for firing, but plenty of cover from air observation. Again, winding trails or tracks leading to small bunkers to house munitions or command posts, accommodation huts and vehicle parks. And then the defensive fortifications, with pill boxes, bunkers, trenches, shielded by wire and minefields. Both on Kedah Peak, and the peaks up to Perak Mountain, observation posts were being built as high as possible above the defensive works.

The whole area was now under a security blanket, the trains running through the area having to have their blinds pulled down, and not stopping at Gurun, while all motor traffic was escorted through in convoys. And there was a heavy police presence, both Civil and Military, with check points and patrols.

To build this, two of the five Indian Auxiliary battalions, the 24th and 29th were here, having only arrived in Malaya, late August, along with a company of both the 5th and 8th, while the 13th was at Jitra. The 13th, 24th and 29th battalions were used for general labour work, while the 5th specialised in rail work and the 8th in road/bridge work. Most of the engineer companies of III Indian Corps were also here, and a heavy policed FMSR rail workforce, grading the rail beds, then laying sleepers and track. A number of Canadian and New Zealand drivers had been borrowed from the airfield construction companies, to operate recently delivered, new earth moving equipment.

As yet there were no fighting units here, except for some advance parties from artillery regiments, the 15th Indian Bde was planned to move in early December. Brigadier Crawford, Chief Engineer of III Corps had his offices in Gurun village, along with an engineering staff, and a couple of artillery officers, while Brigadier Simson, Chief Engineer, Malaya Command, and a number of other staff officers were visiting on a regular basis to co-ordinate the arrival of supplies, stores, and other materials, and review the progress.

In tandem, the work on the Jitra line was continuing to proceed, with the propaganda machine in full swing, promoting its defensive capabilities, with news reel reports of how good it was going to be. In truth, the news reels show the same few pill boxes and trenches, shot at different angles, and with a rotation of different regiments occupying them, but to the outside world the Jitra Line was beginning to look like a defensive fortification worthy of national acclaim.

There had been plans for this, going back to when Lord Gort and Percival had first toured the country on their arrival in December 1940. The plans had taken on more detailed, with the arrival of the III Indian Corps commander, Godwin-Austen, who had increasingly pressed for such a defence. The Jitra line was good for a political statement of defending all of Malaya, but its defensive qualities were badly wanting. What was wanted was a solid backstop.

When they had discussed what units might be used for Operation Matador, it quickly became apparent that most of the Indian units were not sufficiently proficient for mobile operations, being only capable of fixed defensive roles. That meant only the Australians and a few supporting units could be the sword, while the Indian Army, in the main, would have to be the shield. The adoption of Matador, if it should happen, would give them a delaying action option, buying more time for the shield to prepare for what could become the ‘Battle for Malaya’. But whether Matador happened or not, the Indians would hold the Jitra Line, and now this one, with the Australians as the strategic reserve.

Frustratingly, little had been done other than planning and surveying, owing to Civil Government restrictions, but the passing of the Malaya War Act, had sweep them away, and before the end of September, the work had begun. The rail stations at Gurun, Bedong and back in Sungai Petani were all being enlarged with passing loops, and more sidings being added, with a number of magazines, bunkers, and widely spaced warehouses, located in rubber plantations nearby being built.

The Gurun line ran for twenty miles north easterly, from the coast just north of Kedah Peak to Perak Mountain. The first six and a half miles were behind a large drainage canal, with extensive padi fields north of it, and a metalled road running from Yan to the crossroads at the village of Chempedak, sitting behind it. Crossing the main road heading north, the line ran for another 3 miles easterly, again with padi in front, and the lateral road continuing behind. It then met the foothills of the Bintang mountain range, where jungle took over, and the road stopped.

Now the line became a series of outposts, centred on high points or across the trails to be found running through the jungle. Access to, and servicing these outposts was a major concern, and the ones close to Perak Mountain were served from the village of Jeniang, which was accessed by a small metalled road from Gurun, and had a well-defined trail heading north to the mountains. Behind the lines sat Kedah Peak, then extensive rubber plantations for about 5 miles, and then again, the jungle closed in.

Plantation trails were being improved, keeping the twists and turns, not allowing long straight stretches, making it more difficult to follow from the air, but as the work progressed further east, the move into jungle slowed this development. Among the plantations or in small clearings cut from the jungle, buildings or sheds were to be built, for housing men and supplies.

Further forward would come the gun pits, with 1-2 trees removed, sufficient for firing, but plenty of cover from air observation. Again, winding trails or tracks leading to small bunkers to house munitions or command posts, accommodation huts and vehicle parks. And then the defensive fortifications, with pill boxes, bunkers, trenches, shielded by wire and minefields. Both on Kedah Peak, and the peaks up to Perak Mountain, observation posts were being built as high as possible above the defensive works.

The whole area was now under a security blanket, the trains running through the area having to have their blinds pulled down, and not stopping at Gurun, while all motor traffic was escorted through in convoys. And there was a heavy police presence, both Civil and Military, with check points and patrols.

To build this, two of the five Indian Auxiliary battalions, the 24th and 29th were here, having only arrived in Malaya, late August, along with a company of both the 5th and 8th, while the 13th was at Jitra. The 13th, 24th and 29th battalions were used for general labour work, while the 5th specialised in rail work and the 8th in road/bridge work. Most of the engineer companies of III Indian Corps were also here, and a heavy policed FMSR rail workforce, grading the rail beds, then laying sleepers and track. A number of Canadian and New Zealand drivers had been borrowed from the airfield construction companies, to operate recently delivered, new earth moving equipment.

As yet there were no fighting units here, except for some advance parties from artillery regiments, the 15th Indian Bde was planned to move in early December. Brigadier Crawford, Chief Engineer of III Corps had his offices in Gurun village, along with an engineering staff, and a couple of artillery officers, while Brigadier Simson, Chief Engineer, Malaya Command, and a number of other staff officers were visiting on a regular basis to co-ordinate the arrival of supplies, stores, and other materials, and review the progress.

In tandem, the work on the Jitra line was continuing to proceed, with the propaganda machine in full swing, promoting its defensive capabilities, with news reel reports of how good it was going to be. In truth, the news reels show the same few pill boxes and trenches, shot at different angles, and with a rotation of different regiments occupying them, but to the outside world the Jitra Line was beginning to look like a defensive fortification worthy of national acclaim.

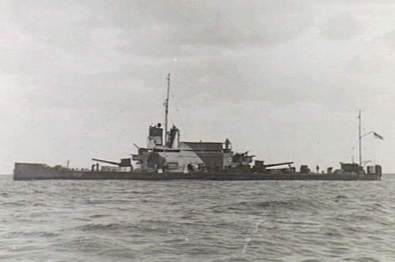

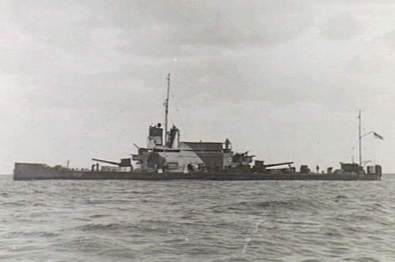

I must applaud your detail & research. As a ex-RN rating who is into history, I must say that I had never heard of this class of ship & their service record before. Kudos.HMCS Prince Henry had arrived mid-morning, and had immediately been given a berth on the north wall of the Naval Dockyard. A very disgruntled looking Insect class river gunboat, HMS Scarab was anchored in the straits, having given up the berth, the servicing of her six-inch guns,

Insect-class gunboat - Wikipedia

Driftless

Donor

As yet there were no fighting units here, except for some advance parties from artillery regiments, the 15th Indian Bde was planned to move in early December.

The defensive works are shaping up, but it sounds like a race to occupy the starting line ahead, I think.

Huff Duff didn't require rotation of antennas, but did have other manual characteristics. Huff Duff required that there first be a detection of a transmitted signal so that the HFDF system could be tuned to that frequency. Land systems were not equipped with rapid automatic signal scanning and detection until 1942, with shipboard systems following later. In the early history of HFDF, a significant part of the time required for a successful direction-find was due to the need to initially detect the signal and tune the HFDF system to that frequency.Part of the success of the British Huff-Duff system was that it was not manual. Using an oscilloscope and an array of antennas receiving from different angles, it was basically instantaneous. For quite some time the Germans Navy thought they were safe transmitting as they used a burst cypher system that kept messages to under a minute. But Huff Duff picked them up anyway.

And, for the first part of the war, signal direction finding aboard aircraft often still involved rotation of directional antennas. There weren't nearly enough HFDF sets to put one on every search aircraft...it was several years into the war before there were enough to have HFDF capability for each British airbase, to detect locations of friendlies so they could be effectively vectored to enemy-aircraft radar contacts...and the HFDF system's own antennas were too large and un-aerodynamic for many aircraft

HFDF was most effective across the frequency range usually used for communication to and from submarines. Longer-wavelength frequencies were less often monitored prior to the extension of automatic scanning to a wider frequency range, because submarines did not have physical space for antennas sized for those longer-wavelength frequencies. So, land-based transmitters operated at such frequencies were, for the first part of the war, mostly not subject to HFDF detection.

And, HFDF based on single detection systems had poor directional accuracy for distant-source signals. This was especially so for shipboard HFDF systems because the EM field effects of the metallic ship structure caused phase distortion of the arriving signal. This was greatly improved by 1944, by establishment of networks of land-based HFDF systems that merged their data in near real time to establish much more accurate source locations, and by extensive engineering development of painstaking calibration procedures for individual ships/antennas/HFDF systems across needed frequency bands.

Ramp-Rat

Monthly Donor

A number of interesting points and questions regarding Anglo Dutch naval matters have arisen. First I believe that the resent post indicates that the British Far East Fleet has just gained its first infantry landing ship. Which while it would soon find itself sunk, if it were to operate of the Malayan East Coast, will provided it operates along the West Coast, will prove itself extremely useful. As the preparations made will ensure that the Japanese have little to no access to shipping in the region, and thus can not land forces behind the British front line. While the British will be able to land commandos behind the Japanese front line, and seriously disrupt their supply chain, and force them to leave significant forces to defend the coast. As for the question of if the Japanese Navy can launch an attack on Sumatra or Java, first of why would they unless they have captured Malaya and Singapore first. There is a massive difference between launching a surprise attack against Pearl Harbour, an isolated island in the vast Pacific Ocean, and driving your fleet into the increasingly constricted waters off the South China Sea. The first was a minor success, were as the second would be a major disaster, costing the Japanese a significant number of losses. Without the capture of Malaya, Singapore and the Philippines, there is no possibility of a surprise. The Japanese fleet would have to fight their way through a series of air, surface and subsurface attacks, in highly restricted waters, by the Americans, British and Dutch. Those old biplane torpedo bombers that the British have, which wouldn’t stand a snowballs chance in hell, of conducting an attack in daylight, will during a night attack inflict significant damage. And it should be remembered that by the time that the Japanese fleet gets level with Singapore, the ships crews will be effectively dead on their feet, having been at action stations, and subjected to repeated attacks for two days. Both the officers and men, will be making increasing mistakes, large and small and small, all leading to a serious loss of efficiency. Such an attack has a very high probability of becoming a catastrophic disaster, with serious losses for the Japanese, and a major boost to allied morale.

The establishment of the series of defence lines in northern Malaya, while very much old school thinking, reminiscent of WWI. Is in the present situation, given the lack of training of the majority of the Indian forces a very good idea. It takes a highly trained and experienced army to conduct truly mobile operations, but simply holding the line and defending prepared positions is a much simpler task. One that is well suited to troops that have gone through basic and basic advanced training. But who have as yet not been in action, or learned the highly advanced skills required to conduct mobile warfare. Unlike in WWI, were such defensive works would have been constructed in a landscape that had been repeatedly subjected to aerial surveillance, and possibly artillery fire, the area picked is essentially virgin territory, with the majority of its cover intact. The British have taken extensive precautions to prevent the Japanese from gaining accurate information or intelligence about the location and formation of these defensive positions. And it will only be when the Japanese run into them that they will begin to develop an understanding of the extent of what they face. Aerial reconnaissance is going to tell them little to nothing, their on the ground intelligence assets will have seen very little, and I doubt that a single Japanese has been allowed into this defence zone. The standard Japanese tactic of executing a hook around the defensive position, and cutting it off from the rear, isn’t going to work, as the only semi open flank is the jungle in land, as the rest is a continuous line. This defensive line serves a number of purposes, as it forces the Japanese to fight on British terms, and to British strengths and Japanese weaknesses. It also serves to protect Singapore from air attacks along with the rest of Malaysia, Japanese aircraft that are attacking these defensive positions, can not be attacking elsewhere. The Japanese do not have the resources or aircraft to carry out attacks against multiple targets, which will allow the British to rotate their fighter aircraft between the northern front and Singapore, thus ensuring that British pilots get some rest.

For the Japanese ground forces, once they have driven the British defenders away from the border, their route south will bring them up to the defence zone. And while they will know of its existence, they will have little to no knowledge of its peculiarities. So once the initial British defenders have retired behind the defence line, and been moved back to rest and reform, the Japanese have the problem of what next. Do they try to bully their way through with an overwhelming attack against one of the strong points defending a route south, while trying to probe for a gap in the line to infiltrate through an exact their standard hook manoeuvre. Or do they seek to close up to the British line and conduct a series of reconnaissance missions, as they try to establish the extent and location of the defences before them. While seeking aerial surveillance, and awaiting the arrival of more artillery other then the organic allocated to the front line divisions. Either way they have a problem, if they try a blitz attack odds are they will get a very bloody nose and find that are no gaps to be exploited. Where as stopping to carry out a complete reconnaissance and prepare a integrated attack plan, including artillery and aircraft, is going to take time. And time is something along with resources that the Japanese are short of, once their advance gets bogged down, their poor logistics in comparison to the British, and the British ability to reinforce their forces with new and fresh formations. Mean that the Japanese have only a limited time frame to achieve their objectives, if they go beyond this time scale, a lot of other operations become increasingly difficult. As the Japanese are forced to increase the limited resources they have available to them, to attempting to achieve their goals in Malaya, to the detriment of their planed operations elsewhere. Should the Japanese take the time to develop a integrated battle plan to break through this British defence line, not only will this allow the British time to develop another defence line behind this one. And they will have added at least a week to their campaign, with no guarantee that their attack will achieve its objectives. As the Japanese are going to have to learn the lessons that it took the British took years to learn, on how to unlock a prepared dug in defensive position during WWI. In just a few weeks given that the last time they encountered such conditions was during the Russian Japanese war of 1904/5, when they had much better logistics and artillery provision. This line stands a very good chance of completely disrupting the Japanese plans, and inducing their first major failure.

RR.

The establishment of the series of defence lines in northern Malaya, while very much old school thinking, reminiscent of WWI. Is in the present situation, given the lack of training of the majority of the Indian forces a very good idea. It takes a highly trained and experienced army to conduct truly mobile operations, but simply holding the line and defending prepared positions is a much simpler task. One that is well suited to troops that have gone through basic and basic advanced training. But who have as yet not been in action, or learned the highly advanced skills required to conduct mobile warfare. Unlike in WWI, were such defensive works would have been constructed in a landscape that had been repeatedly subjected to aerial surveillance, and possibly artillery fire, the area picked is essentially virgin territory, with the majority of its cover intact. The British have taken extensive precautions to prevent the Japanese from gaining accurate information or intelligence about the location and formation of these defensive positions. And it will only be when the Japanese run into them that they will begin to develop an understanding of the extent of what they face. Aerial reconnaissance is going to tell them little to nothing, their on the ground intelligence assets will have seen very little, and I doubt that a single Japanese has been allowed into this defence zone. The standard Japanese tactic of executing a hook around the defensive position, and cutting it off from the rear, isn’t going to work, as the only semi open flank is the jungle in land, as the rest is a continuous line. This defensive line serves a number of purposes, as it forces the Japanese to fight on British terms, and to British strengths and Japanese weaknesses. It also serves to protect Singapore from air attacks along with the rest of Malaysia, Japanese aircraft that are attacking these defensive positions, can not be attacking elsewhere. The Japanese do not have the resources or aircraft to carry out attacks against multiple targets, which will allow the British to rotate their fighter aircraft between the northern front and Singapore, thus ensuring that British pilots get some rest.

For the Japanese ground forces, once they have driven the British defenders away from the border, their route south will bring them up to the defence zone. And while they will know of its existence, they will have little to no knowledge of its peculiarities. So once the initial British defenders have retired behind the defence line, and been moved back to rest and reform, the Japanese have the problem of what next. Do they try to bully their way through with an overwhelming attack against one of the strong points defending a route south, while trying to probe for a gap in the line to infiltrate through an exact their standard hook manoeuvre. Or do they seek to close up to the British line and conduct a series of reconnaissance missions, as they try to establish the extent and location of the defences before them. While seeking aerial surveillance, and awaiting the arrival of more artillery other then the organic allocated to the front line divisions. Either way they have a problem, if they try a blitz attack odds are they will get a very bloody nose and find that are no gaps to be exploited. Where as stopping to carry out a complete reconnaissance and prepare a integrated attack plan, including artillery and aircraft, is going to take time. And time is something along with resources that the Japanese are short of, once their advance gets bogged down, their poor logistics in comparison to the British, and the British ability to reinforce their forces with new and fresh formations. Mean that the Japanese have only a limited time frame to achieve their objectives, if they go beyond this time scale, a lot of other operations become increasingly difficult. As the Japanese are forced to increase the limited resources they have available to them, to attempting to achieve their goals in Malaya, to the detriment of their planed operations elsewhere. Should the Japanese take the time to develop a integrated battle plan to break through this British defence line, not only will this allow the British time to develop another defence line behind this one. And they will have added at least a week to their campaign, with no guarantee that their attack will achieve its objectives. As the Japanese are going to have to learn the lessons that it took the British took years to learn, on how to unlock a prepared dug in defensive position during WWI. In just a few weeks given that the last time they encountered such conditions was during the Russian Japanese war of 1904/5, when they had much better logistics and artillery provision. This line stands a very good chance of completely disrupting the Japanese plans, and inducing their first major failure.

RR.

In this scenario the Japanese would be steamrolling through the central and eastern Dutch East Indies so they don't have to go through South China Sea.As for the question of if the Japanese Navy can launch an attack on Sumatra or Java, first of why would they unless they have captured Malaya and Singapore first. There is a massive difference between launching a surprise attack against Pearl Harbour, an isolated island in the vast Pacific Ocean, and driving your fleet into the increasingly constricted waters off the South China Sea. The first was a minor success, were as the second would be a major disaster, costing the Japanese a significant number of losses. Without the capture of Malaya, Singapore and the Philippines, there is no possibility of a surprise. The Japanese fleet would have to fight their way through a series of air, surface and subsurface attacks, in highly restricted waters, by the Americans, British and Dutch. Those old biplane torpedo bombers that the British have, which wouldn’t stand a snowballs chance in hell, of conducting an attack in daylight, will during a night attack inflict significant damage. And it should be remembered that by the time that the Japanese fleet gets level with Singapore, the ships crews will be effectively dead on their feet, having been at action stations, and subjected to repeated attacks for two days. Both the officers and men, will be making increasing mistakes, large and small and small, all leading to a serious loss of efficiency. Such an attack has a very high probability of becoming a catastrophic disaster, with serious losses for the Japanese, and a major boost to allied morale.

The Insect class gunboats are one of those units that even post war had lots of potential to be used for other missions. Instead of th 6" guns for and aft, having a set of 40mm bofors onboard to provide some AA and surface attack would make them a good riverine inshore unit, changing them to a high angle mount with something like a 4.5" howitzer would work good also. IIRC they also had a tunnel propulsion, where the prop is in a half pipe under the ship, and that let it have a lower draft hull.

The OTL Battle of Kampar is perhaps a good example of what can happen. That action saw cobbled together forces holding their own. If the Malayan Command can force the 5th IJA Division to a standstill, it's awhile until the Imperial Guards can get there to back them up. Even when the Imperial Guards get there, they are less than compliant with GEN Yamashita.For the Japanese ground forces, once they have driven the British defenders away from the border, their route south will bring them up to the defence zone. And while they will know of its existence, they will have little to no knowledge of its peculiarities. So once the initial British defenders have retired behind the defence line, and been moved back to rest and reform, the Japanese have the problem of what next. Do they try to bully their way through with an overwhelming attack against one of the strong points defending a route south, while trying to probe for a gap in the line to infiltrate through an exact their standard hook manoeuvre.

RR.

If Jitra holds for longer than it does in OTL, lessons are learned. If Gurun holds for longer than the OTL, lessons are coalescing. If there is a left flank at Kampar, lessons are applied. The 5th IJA Division may have been bled to less than 50% effectives, with their reinforcements are still weeks away.

A fighting and cohesive retreat is not a dishonor. And it generally saps the attacker/pursuer of its strengths too.

Ramp-Rat

Monthly Donor

The Insect class gunboats are one of those units that even post war had lots of potential to be used for other missions. Instead of th 6" guns for and aft, having a set of 40mm bofors onboard to provide some AA and surface attack would make them a good riverine inshore unit, changing them to a high angle mount with something like a 4.5" howitzer would work good also. IIRC they also had a tunnel propulsion, where the prop is in a half pipe under the ship, and that let it have a lower draft hull.

Personally I think that the failure to put these vessels through a thorough refit in the early thirties, which replaced their steam plant with diesel engines, along with the aft 6 inch gun with a 6 inch howitzer, while replacing the 12 pounders with twin 2 pound Pom Poms, was a serious mistake.

RR.

Fatboy Coxy

Monthly Donor

Hi Cuchulainn, thank you, Wiki doesn't do true justice to how well they did around Tobruk.I must applaud your detail & research. As a ex-RN rating who is into history, I must say that I had never heard of this class of ship & their service record before. Kudos.

Insect-class gunboat - Wikipedia

en.wikipedia.org

Fatboy Coxy

Monthly Donor

Hi jlckansas, wow, where did you get that from!The Insect class gunboats are one of those units that even post war had lots of potential to be used for other missions. Instead of th 6" guns for and aft, having a set of 40mm bofors onboard to provide some AA and surface attack would make them a good riverine inshore unit, changing them to a high angle mount with something like a 4.5" howitzer would work good also. IIRC they also had a tunnel propulsion, where the prop is in a half pipe under the ship, and that let it have a lower draft hull.

Threadmarks

View all 264 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

MWI 41120514d Royal Navy Eastern Fleet OOB MWI 41120618 Shuffling The Pack MWI 41120617 The Ongoing Development Of The Airfields MWI 41120617a RAF Far East Command MWI 41120618 Rommel Retreats To The Gazala Line MWI 41120619 Kondo’s Dilemma MWI 41120620 Matador Is On MWI 41120702 The Race Begins

Share: