Excerpt from “And the Forest Floor Ran Red: The French and Indian War” by Harold D. Weaver (Pittsburgh: Fort, 2007)

Britain’s second success in 1758 has, over the course of time, been called ironic, fitting, and even a strange twist in the war, almost as if written by someone for a script. The taking of Fort Frontenac, a strategic location which helped put Britain on the path to victory in North America over the French, had its plans drawn up by an Acadian. Jean-Baptiste (or John) Bradstreet, a Nova Scotian with an Acadian mother and a British military father, had always been a military man starting with his childhood, growing up in his father’s regiment. It was he who had helped to persuade William Shirley in 1744 to assault and capture Louisbourg from the French during King George’s War[1], and had in fact taken part in the expedition itself. While there, his driving initiative to take part in the action and outstanding organizational capability led to Shirley seeking him out again during the French and Indian War to create and manage a transportation service from Albany to Fort Oswego. He did so with great success, managing to stay in his post when Lord Loudoun took over operations, even being promoted to lieutenant colonel in the process. He greatly improved the logistics and capabilities of the army, as well as improving his own financial situation; Bradstreet would become quiet rich in the process[2]. Despite the welcome wealth, however, what Bradstreet really desired was military glory.

To this end, Bradstreet constantly promoted a plan of his own design, first devised in 1755. Perhaps driven by a desire for more wealth or the trained eye of one who himself delt with supply, Bradstreet focused on the capture of Fort Frontenac on Lake Ontario. This single post was perhaps the most important in all of Canada for it was a strategic location for the French war effort. During times of peace the warehouses at the fort would be overflowing with furs and pelts to be shipped to peace, and even now the same would hold true. However, the flow of goods in the opposite direction was the true prize: arms, ammunition, and the trade goods that were key to maintaining the trade and alliance system that had developed between the Indian nations and the French. From this one point all aid from the French went to their native allies, either south into the backcountry of Pennsylvania and Virginia or farther west, out past the French post at Detroit in into the region around the Great Lakes. Such a strike, if carried out successfully, would wield multiple benefits for the British and colonists alike: the removal of the main French naval base on Lake Ontario, the capture of a vast quantity of trade goods which could be sold elsewhere, depriving all of the forts in the Great Lakes basin essential supplies for the upcoming winter, and the removal of trade goods which bought the native’s services in raiding the frontiers of Pennsylvania and Virginia, lessen the amount of raids while straining the French-Native relationship.

Such a plan was surely impressive, especially after Bradstreet informed Loudoun that he would personally finance the expedition himself. It was made a part of the year’s campaign, but was removed by William Pitt at the same time that Loudoun himself was removed and replaced by James Abercromby. The situation all changed following Ticonderoga; as Abercromby returned from Fort Carillon Bradstreet badgered the defeated commander to give him the men and arms to attack the fort. Humiliated with defeat, and looking for some form of success in what was becoming a disastrous campaign, Abercromby relented on July 13th. Bradstreet would have his operation.

He would work with lightning speed to put his plan into operation; within two weeks Bradstreet had assembled a force of over 5,000 provincials, almost 200 British regulars, and 70 Iroquois warriors. He had also managed to equip them all with bateaux, supplies, and field artillery. Soon after they were on their way westward. The destination was a location known as the Great Carrying Place, as Bradstreet had told his men (and the entire town of Schenectady). After traveling up the Mohawk River, this area was a portage that connected it with Wood Creek, a westward flowing creek which drained into Lake Oneida and, eventually, Lake Ontario. Once they arrived at the Great Carrying Place they would erect a fort to replace Oswego. This would allow the British to trade again with the Six Nations in the area, who had been without easy access to such trade goods for two years. Of course, such elaborately told intentions were not fully true, and it was only after the expedition arrived at the portage were the true plans told. It was true that a fort would be built; however, a majority of the men would continue on with Bradstreet and move to capture Fort Frontenac. At this point, half of the warriors left Bradstreet, while bribes kept the others along with him.

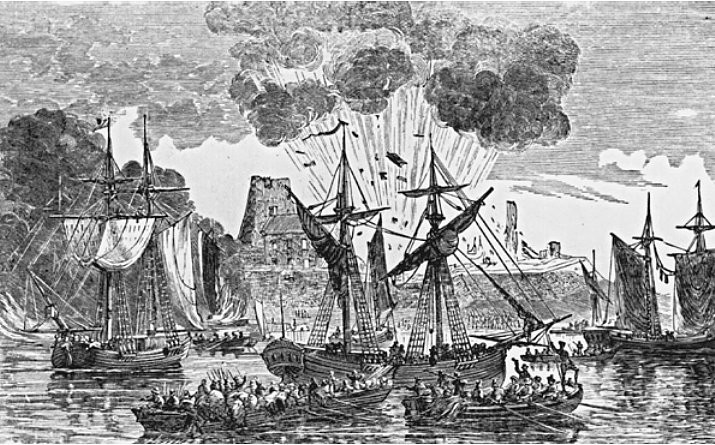

As Brigadier General John Stanwix[3] built the fort with two thousand men, the rest continued on with Bradstreet, lugging their boats and supplies across the portage and into Wood Creek to continue their journey. By August 21st they had made it as far as the ruins of Fort Oswego, camping overnight there. Four days later they beached their boats within a mile of the fort, undetected this entire time, and began to build defenses. The French, surprised at what they were seeing, began to fire cannonballs at them, but it was already too late. The next morning Bradstreet’s men landed the field guns they brought with them, and by August 27th all eight guns were firing on the fort from battery works within 150 yards of the fort. Within an hour and a half a flag of truce was raised over the fort.

For what Bradstreet had seen as such a critical and strategic location for the French in North America, he was dumbfounded by the lack of opposition from the French. The oddity was readily apparent once the truce had been raised: the majority of the men at the fort had, in fact, been called to help defend Fort Carillon. There were only 110 men stationed at the fort, while inside countless women and children, the families of the men stationed there and who had left, huddled for protection. There were plenty of guns and ammunition to defend the fort, but not enough manpower. The French commander, sixty-three year old Major Pierre-Jacques Payen de Noyan[4], understood that he could not maintain his position long enough for reinforcements, nor subject those seeking shelter to the horrors that would befall them in the fort. Bradstreet quickly accepted the surrender of the fort, noticing the amount of fresh bread which he would use to feed his own men, unsure himself of how far away a relief expedition was. The French were allowed to leave the fort provided that they released an equal number of British captives would be released in Canada as well.

With that, Bradstreet and his men began to plunder the fort. Insides was almost unfathomable wealth: hundreds of bales of cloth, seemingly thousands of coats, shirts, and other clothing, deerskins, beaver pelts, furs, ammunition, guns, powder – all seemed to stack up to the roofs of the buildings and then overflow them. There were not enough men to carry everything back with them; instead, they made off with £35,000[5] in their boats while destroying the rest of the goods, the fort, and the entire French fleet on the lake. The troops began their return leg on August 28th, the French supply system in shambles and likely broken beyond repair – all done by a man who had Acadian blood himself, and made all the sweeter by knowing that not a single man had been lost on this expedition.

___

[1] Bradstreet was actually at

the French raid on Canso, which is where he would get the idea for the raid on the fort later on during that war. This, as well as growing up in the area, helped to provide his opinions with weight, along with the passion behind his plan which will be seen in his plan for the French and Indian War.

[2] This, of course, is not uncommon for quarter masters at this time; after all, surely one can take a little off the top is less of a loss than what was happening before they put their skills to use?

[3] Born about 1690, Stanwix entered the army in 1706 and rose through the ranks. Besides his military career he was also appointed to the government of Carlisle in 1750, after he represented it in Parliament 1741. This provides an ironic footnote in history, as he was stationed in Carlisle, Pennsylvania during this war before being reassigned north to take part in Bradstreet's expedition.

[4] Sadly, I was not able to find more information on this individual, other than what was stated above

[5] This was quite a haul; the comperative cost to today would exceed $700,000