Devvy

Donor

1992 - Cardiff

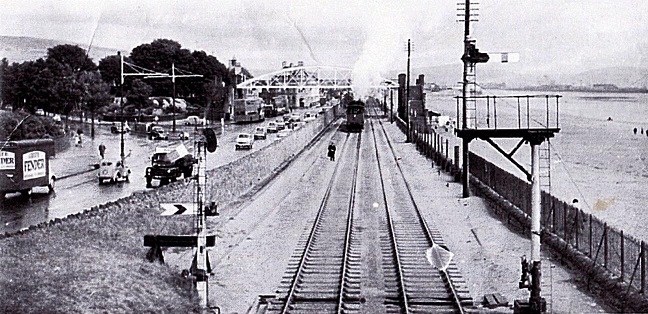

Cardiff Bay before renovation.

(*1) The city was recognised as the capital city of Wales on 20 December 1955, by a written reply by the Home Secretary Gwilym Lloyd George. Welsh local authorities had been divided on the issue of where a new capital of Wales should be, with only 76 out of 161 opting for Cardiff in a 1924 poll, organised by the South Wales Daily News. Because of the divided opinion, discussions had not been revived on the issue until 1950, and Cardiff thus took steps to promote its 'Welshness'. The stalemate between Cardiff and Caernarfon (and Aberystwyth) wasn't broken until Cardiganshire County Council decided to support Cardiff and, in a new local authority vote, 134 out of 161 voted for the city. Although the city hosted the Commonwealth Games in 1958, Cardiff only became a centre of national administration with the establishment of the Welsh Office in 1964, which later prompted the creation of various other public bodies such as the Arts Council of Wales and the Welsh Development Agency, most of which were based in Cardiff.

However, the coal exports from which Cardiff had grown had already began to dwindle by the 20th Century. By 1932, in the depths of the Great Depression which followed the 1926 United Kingdom general strike, coal exports had fallen to below 5 million tons, and dozens of locally owned ships were laid-up. It was an era of depression from which Cardiff never really recovered, and despite intense activity at the port during the Second World War, coal exports continued to decline, finally ceasing in 1964.The East Moors Steelworks closed in 1978 and Cardiff lost population during the 1980s, consistent with a wider pattern of counter urbanisation in Britain. During this period the Cardiff Bay Development Corporation was founded in 1987, and was active in promoting the redevelopment of south Cardiff. It had several objectives, but it's primary one (as befit it's name) was the regeneration of the areas around Cardiff Bay, which had been extremely neglected following the withdrawal of dock activities, and working with other regeneration projects in South Wales; a region struggling overcome deindustrialisation.

One of the major projects in Cardiff at the turn of the decade, was the construction of the Cardiff Bay Barrage, to stablise the dock waters, and the regeneration of the areas around it. The area was ripe for rebuilding, and looked set to play host to a large array of new housing, as well as an entertainment area and plenty of watersport mini-hubs dotted around the Bay. Tied in to this, were new roads - wide avenues intended not just for motor traffic, but pedestrians and ideally a rapid transit system for the area (*2). Funds, however, were not forthcoming for such an expensive conversion, given that the new light rail system would have to be threaded around central Cardiff itself as well to be of any use. The scheme was overhauled in 1988 to create a regional metro system, winning backing from major institutions such as (the then) University College Cardiff for new halls of residence for students, the growing Welsh Development Office (prior to it's financial controversy) and a new International Exhibition Centre.

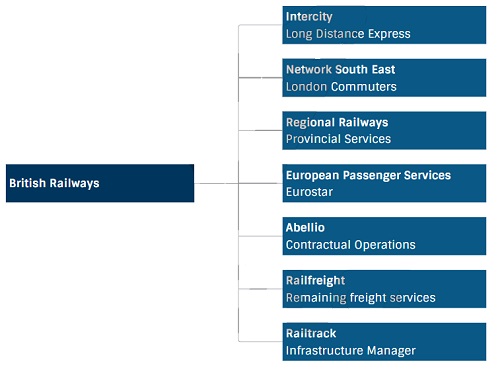

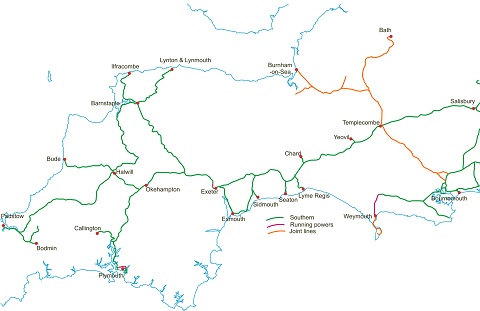

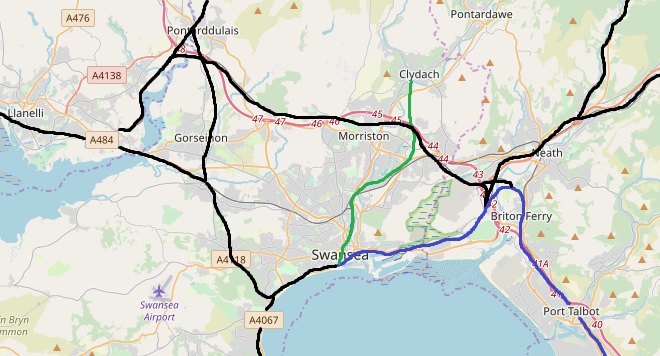

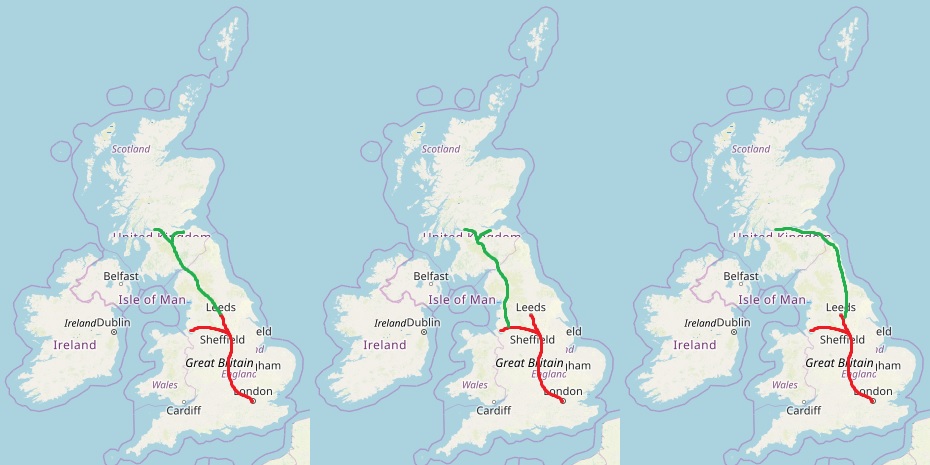

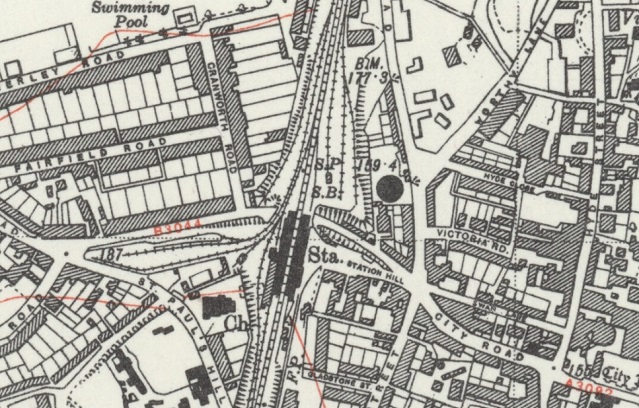

The Cardiff Metro map

As with other cities, British Rail was only more than happy to reduce it's network size, handing over expensive urban track mileage and the responsibility for operating services which attracted complaints from crowding at peak rush hour, and had little usage outside of this window. Only minor works would be needed to reroute trains from the tracks to be handed over, and from Cardiff's view, only minor changes were needed to form the transit network (*3), although station construction at new sites would continue over the following decade, thanks to EEC funding to what remains a European region less developed than the rest.

1992 - "Crossing the Severn", by Bob McAlpine

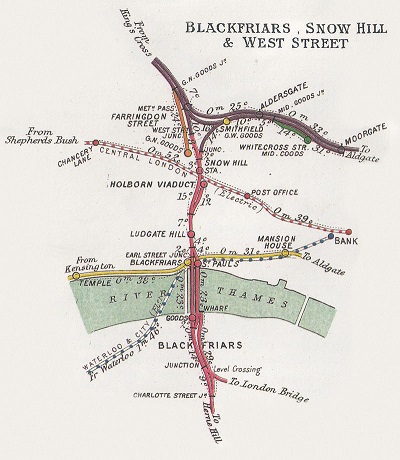

The Severn Channel has long presented a barrier to traffic between England and South Wales. The old Aust Ferry, dating from 1829 ferried goods, and later vehicles across the Severn - the only other option was otherwise a 60 mile round trip via Gloucester, far upstream. Bridge proposals had come and gone for decades, until the coming of the railways, and growing coal industry in South Wales demanded faster connections. A rail bridge at Sharpness opened in 1879, and later followed by the major Severn Tunnel in 1886 brought South Wales firmly on to the UK rail network - and allowed the GWR to operate a train-based car shuttle to operate under the Severn.

The original Severn Bridge under construction.

Post World War II, plans advanced for the motorway network, and the road based Severn Bridge began construction in 1961, and completed in 1966. Within 20 years though, the rise in road traffic had rendered the bridge "busy", with projections that by 1990 the bridge would be at full capacity. Consultants reported in 1986 that a new bridge should be built, shortly downstream from the existing bridge.

Tied in to this road-based decision were other factors. The Severn Tunnel, now owned by the national British Rail, was sound and of good clearances, but leaked water at such a rate that continual pumping was required to keep it from flooding. Despite attempts to brickline the tunnel to make it more watertight, the water pressure in the surrounding groundwater began to pop bricks out of the lining. Water pressure was such that if the pumps and fans were turned off, it was estimated the tunnel would completely flood in less then 30 minutes (*4). The necessity to keep the tunnel operating, was made all the more important following the closure of the route across the Severn Rail Bridge; two barges had collided with the bridge in 1960, followed by another tanker hitting another pier later, resulting in BR assessing the bridge as "beyond economic repair". Without the Severn Tunnel, trains from London to Cardiff would have to be routed via Gloucester, adding on almost an hour to travel time. Added to this was the existing electrification from London as far as Didcot Junction, with the density of traffic encouraging further extension of this system as far as Bath, Bristol and Swansea for both passenger and freight traffic.

Other energy-based proposals came to the fore at the same time. A 1987 study for a tidal barrage suggested using a site just downstream from the Severn (Road) Bridge, costing approx £1.5 billion, and generating 2.75TWh of electricity per year, or an average of 313MW throughout the year. Using the site over the English Stones would avoid any issue with the docks at Cardiff or Portishead, and so far smaller locks could be used to facilitate boat access up the River Severn towards Gloucester. All these factors slowly coalesced during the 1980s, and then during the concept build of Dornoch Firth Bridge, a combined rail & road bridge in Scotland. It's success in delivering the combined solution allowed other larger schemes combining different concepts to provide an integrated piece of infrastructure to be suggested with realism.

With the Government in power looking for a private sector solution, bids were duly received from three consortia. The new combined crossing would be built roughly where the Severn Tunnel sat, between England and Wales, and making use of the English Stones as a point to build upon. The eventual design would see a motorway of three lanes in each direction, as well as a full four track railway in between the motorway carriageways across the bridge, underneath which would sit a barrage, with sets of turbine sluices between each set of supports. A small set of locks at the middle, where the road & rails were at the highest would allow continued boat access to the River Severn. A set of windbreakers on either side of each motorway carriageways would reduce any crosswind effects on road vehicles, with trains protected by a further inner set of windbreakers to further reduce any crosswinds. (*5)

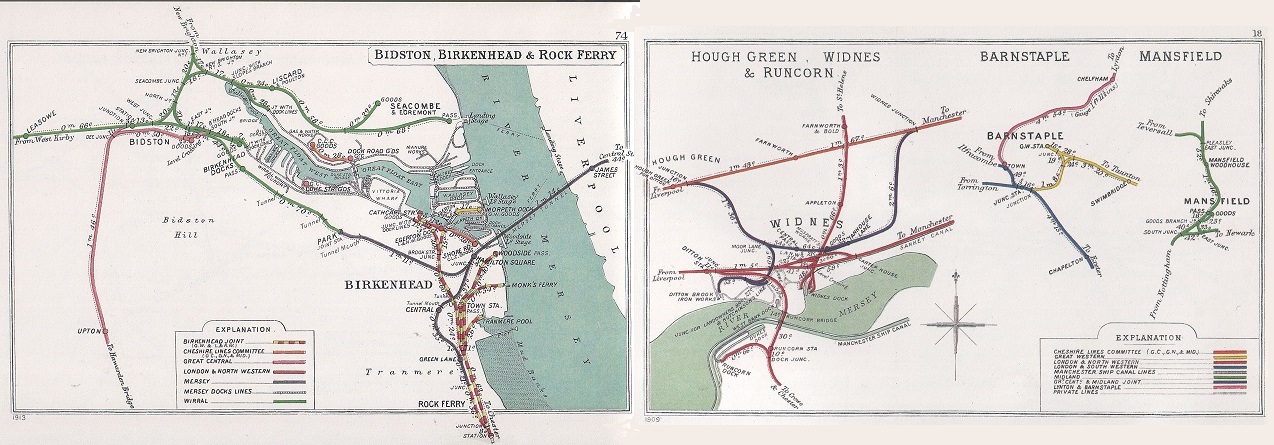

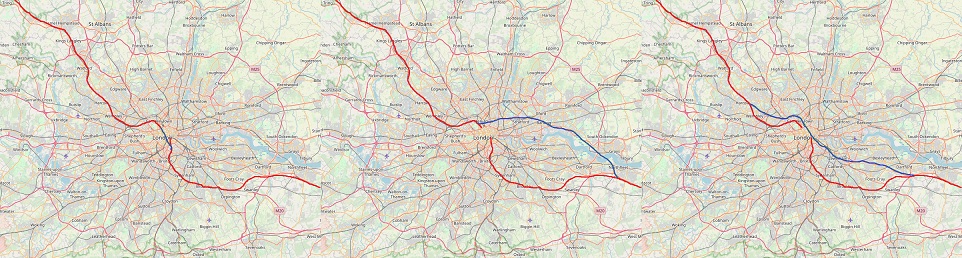

The new bridge links in to existing road and rail routes.

Disagreements over the subsidy for the electricity generated in order to make the power generation economically viable continued to hamper discussions between the Government and all three consortia, along with a vocal minority (*6) involved in environmental protests. With the eventual withdrawal of the barrage, the project fell back to a combined road-rail bridge. Disagreements over even that arrangement, given the lack of subsidised electricity profits to justify the construction costs continued to hamper the agreement when two consortia suggested billing British Rail for each train crossing the bridge, at which point BR would threaten to walk away and continue using the Severn Tunnel which required significant maintenance, but would still be cheaper then the private sector suggestions.

A subsequent agreement reached later allowed the builder to levy tolls on the cars crossing the bridge, whilst a defined contribution from British Rail, matched by the Ministry of Transport ensured untolled rail access across it with a convoluted maintenance regime. This meant the Severn Tunnel could eventually be closed - saving a large amount of expenditure on maintenance and water pumping. It would also provide the stepping stones for electrification, which currently terminated just west of Didcot, covering suburban services but not the Intercity services; something which was under heavy study by British Rail for extension given the short distances to electrify to convert services to Bristol, and then Swansea to electric traction. The four track solution would provide capacity for the future, with passenger numbers having continued to rise on average throughout the 1980s. Linking in directly to the quadruple track westbound to Newport and Cardiff, it would allow separation between the local passenger & freight workings (*7) on one set of tracks, and the faster Intercity services to/from London and elsewhere on the other track, whilst also providing redundancy. This meant the total bridge width would be circa 50 metres - one of the widest bridges in the world, although supported every 80 metres. The bridge, later named the "Bevan Bridge" (*8) in memory of the famous Welsh politician, chiefly responsible for the creation of Britain's NHS, opened in 1999 in a ceremony attended by the Prince of Wales on the day after the 40th anniversary of his investiture as the Prince of Wales. The Severn Tunnel was filled (to avoid any subsidence to the bridge above), and the pumps turned off. Today it is a thing of speculation for enthusiasts and historians, with trains today taking the trip over the bridge with passengers able to admire the spectacular view between the windbreaker slats.

--------------------

(*1) Credit where it's due; basically the background chapters are from Wikipedia.

(*2) OTL plans were to ditch the Cardiff Bay Branch and convert it to light rail / tram system.

(*3) See map, but the routes are easily segregateable. BR Rhymney Line services now transit via a short rebuilt chord (closed during Beeching but still existing) from Energlyn to Taffs Well, and then continue down to Cardiff via the City Route (via western Cardiff).

(*4) All true.

(*5) I ummed and arred over including this project. The Severn Barrage has been suggested repeatedly over the decades, and the Second Severn Crossing is going ahead anyway. The barrage went ahead in the first draft of this chapter, and was subsequently removed following discussion in the comments in this thread. Rail is included, unlike OTL; you only have to look at the troubles in OTL for the difficulties in providing electrification through a very damp and wet tunnel to see the difficulties. See: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-wales-politics-44690614

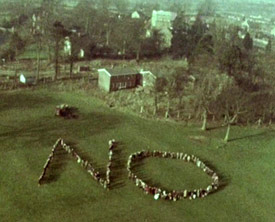

(*6) As always, it's only a minority who can be bothered to actually protest something.

(*7) Due to the many heavy freight workings in South Wales.

(*8) The best name I could come up with!

-------------------

Other notes;

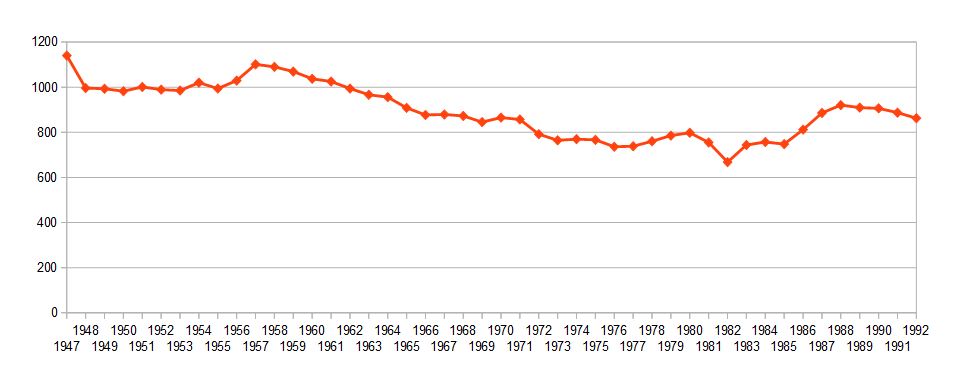

Well by this point it's fairly obvious BR is still under heavy financial pressure; small rail routes which go nowhere are still closing. Electrification is still continuing at a slow pace with Government funding only slightly different to OTL, and much of the infrastructure works tied in to the major projects; Pullman, Channel Tunnel, Britannia Airport. This is a BR network which is still too large for the 1970s and 1980s - but obviously that will shift around when the 1990s/2000s come with rising congestion, especially around the cities.

Cardiff Bay before renovation.

(*1) The city was recognised as the capital city of Wales on 20 December 1955, by a written reply by the Home Secretary Gwilym Lloyd George. Welsh local authorities had been divided on the issue of where a new capital of Wales should be, with only 76 out of 161 opting for Cardiff in a 1924 poll, organised by the South Wales Daily News. Because of the divided opinion, discussions had not been revived on the issue until 1950, and Cardiff thus took steps to promote its 'Welshness'. The stalemate between Cardiff and Caernarfon (and Aberystwyth) wasn't broken until Cardiganshire County Council decided to support Cardiff and, in a new local authority vote, 134 out of 161 voted for the city. Although the city hosted the Commonwealth Games in 1958, Cardiff only became a centre of national administration with the establishment of the Welsh Office in 1964, which later prompted the creation of various other public bodies such as the Arts Council of Wales and the Welsh Development Agency, most of which were based in Cardiff.

However, the coal exports from which Cardiff had grown had already began to dwindle by the 20th Century. By 1932, in the depths of the Great Depression which followed the 1926 United Kingdom general strike, coal exports had fallen to below 5 million tons, and dozens of locally owned ships were laid-up. It was an era of depression from which Cardiff never really recovered, and despite intense activity at the port during the Second World War, coal exports continued to decline, finally ceasing in 1964.The East Moors Steelworks closed in 1978 and Cardiff lost population during the 1980s, consistent with a wider pattern of counter urbanisation in Britain. During this period the Cardiff Bay Development Corporation was founded in 1987, and was active in promoting the redevelopment of south Cardiff. It had several objectives, but it's primary one (as befit it's name) was the regeneration of the areas around Cardiff Bay, which had been extremely neglected following the withdrawal of dock activities, and working with other regeneration projects in South Wales; a region struggling overcome deindustrialisation.

One of the major projects in Cardiff at the turn of the decade, was the construction of the Cardiff Bay Barrage, to stablise the dock waters, and the regeneration of the areas around it. The area was ripe for rebuilding, and looked set to play host to a large array of new housing, as well as an entertainment area and plenty of watersport mini-hubs dotted around the Bay. Tied in to this, were new roads - wide avenues intended not just for motor traffic, but pedestrians and ideally a rapid transit system for the area (*2). Funds, however, were not forthcoming for such an expensive conversion, given that the new light rail system would have to be threaded around central Cardiff itself as well to be of any use. The scheme was overhauled in 1988 to create a regional metro system, winning backing from major institutions such as (the then) University College Cardiff for new halls of residence for students, the growing Welsh Development Office (prior to it's financial controversy) and a new International Exhibition Centre.

The Cardiff Metro map

As with other cities, British Rail was only more than happy to reduce it's network size, handing over expensive urban track mileage and the responsibility for operating services which attracted complaints from crowding at peak rush hour, and had little usage outside of this window. Only minor works would be needed to reroute trains from the tracks to be handed over, and from Cardiff's view, only minor changes were needed to form the transit network (*3), although station construction at new sites would continue over the following decade, thanks to EEC funding to what remains a European region less developed than the rest.

1992 - "Crossing the Severn", by Bob McAlpine

The Severn Channel has long presented a barrier to traffic between England and South Wales. The old Aust Ferry, dating from 1829 ferried goods, and later vehicles across the Severn - the only other option was otherwise a 60 mile round trip via Gloucester, far upstream. Bridge proposals had come and gone for decades, until the coming of the railways, and growing coal industry in South Wales demanded faster connections. A rail bridge at Sharpness opened in 1879, and later followed by the major Severn Tunnel in 1886 brought South Wales firmly on to the UK rail network - and allowed the GWR to operate a train-based car shuttle to operate under the Severn.

The original Severn Bridge under construction.

Post World War II, plans advanced for the motorway network, and the road based Severn Bridge began construction in 1961, and completed in 1966. Within 20 years though, the rise in road traffic had rendered the bridge "busy", with projections that by 1990 the bridge would be at full capacity. Consultants reported in 1986 that a new bridge should be built, shortly downstream from the existing bridge.

Tied in to this road-based decision were other factors. The Severn Tunnel, now owned by the national British Rail, was sound and of good clearances, but leaked water at such a rate that continual pumping was required to keep it from flooding. Despite attempts to brickline the tunnel to make it more watertight, the water pressure in the surrounding groundwater began to pop bricks out of the lining. Water pressure was such that if the pumps and fans were turned off, it was estimated the tunnel would completely flood in less then 30 minutes (*4). The necessity to keep the tunnel operating, was made all the more important following the closure of the route across the Severn Rail Bridge; two barges had collided with the bridge in 1960, followed by another tanker hitting another pier later, resulting in BR assessing the bridge as "beyond economic repair". Without the Severn Tunnel, trains from London to Cardiff would have to be routed via Gloucester, adding on almost an hour to travel time. Added to this was the existing electrification from London as far as Didcot Junction, with the density of traffic encouraging further extension of this system as far as Bath, Bristol and Swansea for both passenger and freight traffic.

Other energy-based proposals came to the fore at the same time. A 1987 study for a tidal barrage suggested using a site just downstream from the Severn (Road) Bridge, costing approx £1.5 billion, and generating 2.75TWh of electricity per year, or an average of 313MW throughout the year. Using the site over the English Stones would avoid any issue with the docks at Cardiff or Portishead, and so far smaller locks could be used to facilitate boat access up the River Severn towards Gloucester. All these factors slowly coalesced during the 1980s, and then during the concept build of Dornoch Firth Bridge, a combined rail & road bridge in Scotland. It's success in delivering the combined solution allowed other larger schemes combining different concepts to provide an integrated piece of infrastructure to be suggested with realism.

With the Government in power looking for a private sector solution, bids were duly received from three consortia. The new combined crossing would be built roughly where the Severn Tunnel sat, between England and Wales, and making use of the English Stones as a point to build upon. The eventual design would see a motorway of three lanes in each direction, as well as a full four track railway in between the motorway carriageways across the bridge, underneath which would sit a barrage, with sets of turbine sluices between each set of supports. A small set of locks at the middle, where the road & rails were at the highest would allow continued boat access to the River Severn. A set of windbreakers on either side of each motorway carriageways would reduce any crosswind effects on road vehicles, with trains protected by a further inner set of windbreakers to further reduce any crosswinds. (*5)

The new bridge links in to existing road and rail routes.

Disagreements over the subsidy for the electricity generated in order to make the power generation economically viable continued to hamper discussions between the Government and all three consortia, along with a vocal minority (*6) involved in environmental protests. With the eventual withdrawal of the barrage, the project fell back to a combined road-rail bridge. Disagreements over even that arrangement, given the lack of subsidised electricity profits to justify the construction costs continued to hamper the agreement when two consortia suggested billing British Rail for each train crossing the bridge, at which point BR would threaten to walk away and continue using the Severn Tunnel which required significant maintenance, but would still be cheaper then the private sector suggestions.

A subsequent agreement reached later allowed the builder to levy tolls on the cars crossing the bridge, whilst a defined contribution from British Rail, matched by the Ministry of Transport ensured untolled rail access across it with a convoluted maintenance regime. This meant the Severn Tunnel could eventually be closed - saving a large amount of expenditure on maintenance and water pumping. It would also provide the stepping stones for electrification, which currently terminated just west of Didcot, covering suburban services but not the Intercity services; something which was under heavy study by British Rail for extension given the short distances to electrify to convert services to Bristol, and then Swansea to electric traction. The four track solution would provide capacity for the future, with passenger numbers having continued to rise on average throughout the 1980s. Linking in directly to the quadruple track westbound to Newport and Cardiff, it would allow separation between the local passenger & freight workings (*7) on one set of tracks, and the faster Intercity services to/from London and elsewhere on the other track, whilst also providing redundancy. This meant the total bridge width would be circa 50 metres - one of the widest bridges in the world, although supported every 80 metres. The bridge, later named the "Bevan Bridge" (*8) in memory of the famous Welsh politician, chiefly responsible for the creation of Britain's NHS, opened in 1999 in a ceremony attended by the Prince of Wales on the day after the 40th anniversary of his investiture as the Prince of Wales. The Severn Tunnel was filled (to avoid any subsidence to the bridge above), and the pumps turned off. Today it is a thing of speculation for enthusiasts and historians, with trains today taking the trip over the bridge with passengers able to admire the spectacular view between the windbreaker slats.

--------------------

(*1) Credit where it's due; basically the background chapters are from Wikipedia.

(*2) OTL plans were to ditch the Cardiff Bay Branch and convert it to light rail / tram system.

(*3) See map, but the routes are easily segregateable. BR Rhymney Line services now transit via a short rebuilt chord (closed during Beeching but still existing) from Energlyn to Taffs Well, and then continue down to Cardiff via the City Route (via western Cardiff).

(*4) All true.

(*5) I ummed and arred over including this project. The Severn Barrage has been suggested repeatedly over the decades, and the Second Severn Crossing is going ahead anyway. The barrage went ahead in the first draft of this chapter, and was subsequently removed following discussion in the comments in this thread. Rail is included, unlike OTL; you only have to look at the troubles in OTL for the difficulties in providing electrification through a very damp and wet tunnel to see the difficulties. See: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-wales-politics-44690614

(*6) As always, it's only a minority who can be bothered to actually protest something.

(*7) Due to the many heavy freight workings in South Wales.

(*8) The best name I could come up with!

-------------------

Other notes;

Well by this point it's fairly obvious BR is still under heavy financial pressure; small rail routes which go nowhere are still closing. Electrification is still continuing at a slow pace with Government funding only slightly different to OTL, and much of the infrastructure works tied in to the major projects; Pullman, Channel Tunnel, Britannia Airport. This is a BR network which is still too large for the 1970s and 1980s - but obviously that will shift around when the 1990s/2000s come with rising congestion, especially around the cities.

Last edited: