Mishin and TsKBEM were enjoying mixed - but improving - fortunes in 1968. While they had managed to see a Soviet Cosmonaut reach the Moon ahead of the Americans, they couldn’t achieve either the Lunar Orbital or Landing missions until the N1 was working reliably, and that was their main pacing item. Following the decidedly below-expected results of the first two launches, it was eventually determined that the Pogo Oscillations that almost ended the 2nd N1 launch was induced by a complex interaction of the many propellant lines vibrating at a frequency that was harmonic with the launch vehicle structure. Furthermore, when the pre-programmed shutdown of some of the first stage engines (to reduce the accelerative stresses on both the launch vehicle and, when manned, the crew) occurred, the sudden 25% reduction in thrust caused the lowermost portion of the Block A, where the engines were mounted, to ‘ping’ back a bit, which affected the propellant flow to the remaining engines. Once the rest of the N1 fell a bit back into them, the propellant flow would increase again and push the engines into the LV again. If these two events were to match in their frequency, the result would be an ever-increasing oscillation that, if left unchecked, carried the strong potential to tear the entire LV apart.

With these likely causes of Launch Vehicle Failure identified, a series of measures were introduced to mitigate them. The use of bellows in some of the propellant lines, while others had their pipes modified to allow inert gas to surround them to change their resonance frequency, combined with dampening mechanisms were hoped to suppress the oscillations and permit successful flights. The biggest problem, however, was that there was no time to install them into the next N1 flight. They would just have to hope for the best.

In the February of 1968, the N1 was launched on its third launch attempt. As was feared, once the first engine shutdown occurred, the Pogo built up rapidly, and before the point where they could safely fire the Block B to allow mission continuation, the N1 began to break apart, and Range Safety were forced to destroy it 136.14 seconds into the flight. Again, the N1 had failed before the Block A had finished its job.

Again, the failure was investigated, but it was obvious to the engineers what had caused this third N1 to fail. And all they could really do at this point was wait until the modifications to the N were complete, and that meant losing perhaps several months as the American Saturn V was put through its paces. The fear for Mishin was that any more delays like this would allow the US to overtake them, and he knew that they were slowly catching up.

Indeed, in the January of that year, Apollo 5 had been launched. An unmanned test of their Lunar Module (LEM) launched on the Saturn IB, in fact, the same Saturn IB that had been intended for Apollo 1 which had escaped damage in that Fatal Accident.

Apollo 5 had been delayed due to numerous difficulties with the LEM, mainly with building it, and most recently with the failed test of another LEM at the Grumman manufacturing plant, when the right glass windows and acrylic glass cover had shattered when attempting the cabin pressurisation test, resulting in the decision to replace the LM-1 windows with aluminium plates as a precaution.

Once in Orbit, despite some problems with the Descent Stage, mainly that its onboard guidance computer terminated the first burn after just 4 seconds, the next two manually controlled tests worked well enough to permit the mission to continue. Following this, a “fire in the hole” ignition of the ascent stage engine was performed, to simulate a landing abort during descent to the Lunar Surface, after which another burn was made of the ascent engine. After less than 12 hours, the test was concluded, and the two stages controls were terminated, their low orbits ensuring they would re-enter within weeks at the most.

NASA’s next big test came in the April of that year. Through reports from the CIA, certain, select NASA staff were aware that the USSR had recently had a failed N1 launch, and that they weren’t out of the Race yet. But they needed their Saturn V to work reliably and that meant another launch to be sure that Apollo 4 hadn’t been a fluke.

The objective was to send the unmanned Apollo CSM on an effective Trans-Lunar Trajectory before using the SM engine for a Direct-Return Abort, to demonstrate the ability to do so. For the first 120 seconds of the flight, it was flawless.

Following the centre-engine shutdown of the first stage, the Saturn V began to experience severe Pogo Oscillations, and at T+133 seconds, pieces of the spacecraft adapter that attached the CSM to the Saturn V were recorded to be breaking off. Then the J-2 engines of the S-II experienced their own problems, with the No.2 engine suffering a performance drop at T+225s, worsening at T+319s before being shut off altogether by the IU at T+412s, after which engine No.3 shut down as well. The IU compensated for this by burning the remaining J-2 engines for almost a minute longer than planned, with a 29 second extension in the S-IVB stage burn time. Even so, the orbit was rather elliptical as opposed to the planned circular 100nm orbit. In spite of this, once the two-orbit vehicle readiness checkout was completed, the S-IVB was commanded to fire again for simulated TLI, and didn’t.

With the S-IVB unable to be restarted, it was decided to use the CSM itself to repeat the Apollo 4 test with the CSM placing itself into a high orbit before being re-entered using the SM engine. Despite the engine failures, NASA had already been aware of some of the problems and decided that they had gathered sufficient data from the flight, so a potential third unmanned test was scrubbed.

The next flight in the Apollo Programme was Apollo 7, the first NASA three-man mission, taking Walter M. Schirra, Donn F. Eisele, and R. Walter Cunningham into LEO for an 11-day shakedown flight of the Apollo Block II. The flight itself was good, the Saturn IB taking the Apollo CSM into LEO. Once in orbit, they separated from the S-IVB and simulated the Lunar Module Rendezvous and Docking procedure, where one of the adapter panels had failed to properly deploy, reinforcing the decision to completely separate and jettison the panels on all subsequent flights.

Things began to go South quickly following the SM engine burns, Schirra had already been unhappy about the less-than-ideal Launch Abort conditions (given that Apollo 7 still had the Block I seats which weren’t as capable with Hard Land Landings than the Block II seats), he then developed a severe head cold which combined with the dissatisfaction with the food selection and the cumbersome waste collection system (that needed 30 minutes to use and made a bad smell), led Schirra to begin to “talk back” to Mission Control. The result of this was that even though Apollo 7 did complete all of its technical objectives, and therefore allowing Apollo 8 to proceed, these particularly terse exchanges led to NASA management deciding to reject Eisele and Cunningham for future missions, Schirra having already announced that Apollo 7 would be his last mission.

Although originally planned to be the second CSM/LEM test in MEO, in the August of 1968, it was decided to make Apollo 8 a special C-Prime mission that would take only the CSM to the Moon. NASA was aware that the Soviets had a launch vehicle that could take their own Cosmonauts to the Moon, and that they’d likely be working out its flaws, and if they managed to enter Lunar Orbit first, they would have good as won the race.

On the 21st December 1968, the Saturn V carried the CSM with astronauts Frank F. Borman (Cmdr), James A Lovell (CMP), and William A. Anders (LMP). Once TLI was completed, the CSM was jettisoned from the S-IVB stage which five fours later had its remaining propellant vented changing its trajectory to a 0.99 x 0.92 AU Solar Orbit. The only really serious issue came when Borman vomited twice and suffered about of diarrhoea, which was initially attributed to either a 24-hour flu or an adverse reaction to the Seconal sleeping pill he’d taken earlier - it wouldn’t be until later that it would be determined that he had experienced Space Adaptation Syndrome.

Three days later, and Apollo 8 conducted a 4m13s burn to brake the CSM into Lunar Orbit, since this burn had to occur while the Moon was between Apollo 8 and the Earth, Mission Control would only be aware of if it succeeded after they were safely in Lunar Orbit. Fortunately, at exactly the expect time of reacquisition, the signal from Apollo 8 came back and the status of the spacecraft was given, before Lovell described the Lunar Surface. In it’s fourth orbit, the Apollo 8 crew witnessed Earthrise for themselves, the Earth rising over the bleak Lunar Landscape, and on the ninth orbit, the crew read the first ten verses of the Book of Genesis.

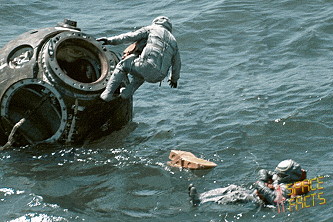

At the tenth orbit, the crew had to fire the SPS again to take them out of Lunar Orbit and back to Earth, and again, the burn had to be performed while they were at the Moon’s Far Side. And again, the spacecraft telemetry was reacquired at the exact predicted moment, Apollo 8 was on its way home, slashing down South of Hawaii on the 27th of December.

As for the Soviets, with the modifications made to the N1 Block A, it received its first completely successful launch at the end of October, and it was hoped that they could perform a Lunar Orbit Mission early in the next year. Vladimir Komarov and Gherman Titov were selected for this mission. Komarov’s skill with manually piloting the malfunctioning Soyuz 1 spacecraft made him a good choice for piloting the Soyuz LOK should its onboard guidance systems fail for any reason.

The announcement of the Apollo 8 mission actually going to the Moon caught them all off-guard, they had not expected NASA to take the risk with as little experience with the Saturn V and Apollo as they had under their belts. Based on this new revelation, they concluded that NASA would likely be able to get their own Men on the Moon by Apollo 11, if not 10. This was worrying news for the TsKBEM, their existing plans called for a Lunar Orbital Test Flight of the LOK and LK individually, followed by testing them together before committing to the Manned Lunar Landing. With NASA accelerating their schedule, they would need to cut some of their missions if they wanted to come first.

It was decided that the N11 flights had provided sufficient data on the Soyuz 7K-LOK, LK Lander, and the Block D stage to permit an acceleration of their own schedule. It was decided that the next N1 would perform its planned Lunar Orbit mission, before the next two would be used for the first Lunar Landing Mission. Such a profile was extremely risky, but they concluded that all the individual components of the N1-L3 complex were working well now, and that the risks could be afforded.