You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

FOR WANT OF THE HAMMER

- Thread starter tuareg109

- Start date

tuareg109

Banned

I thought Scaurus' co-consul Titus something died, not the alive-in-the-update Vettius.

Scaurus is not Consul, he is Princeps Senatus.

Titus Bruttius was assassinated.

Lucius Vettius escorted Saturninus to Ostia and stayed for several days, arriving back in Rome in today's update.

EDIT: Nevermind, found it! Sorry! Fix't.

tuareg109

Banned

.....Meanwhile in Hispania?

Aaaand that's being planned as I write; I've only planned to mid-October, after all.

tuareg109

Banned

FOR WANT OF THE HAMMER

THE FIRST GREAT GRAIN ROBBERY PART 7, 647 AVC

THE FIRST GREAT GRAIN ROBBERY PART 7, 647 AVC

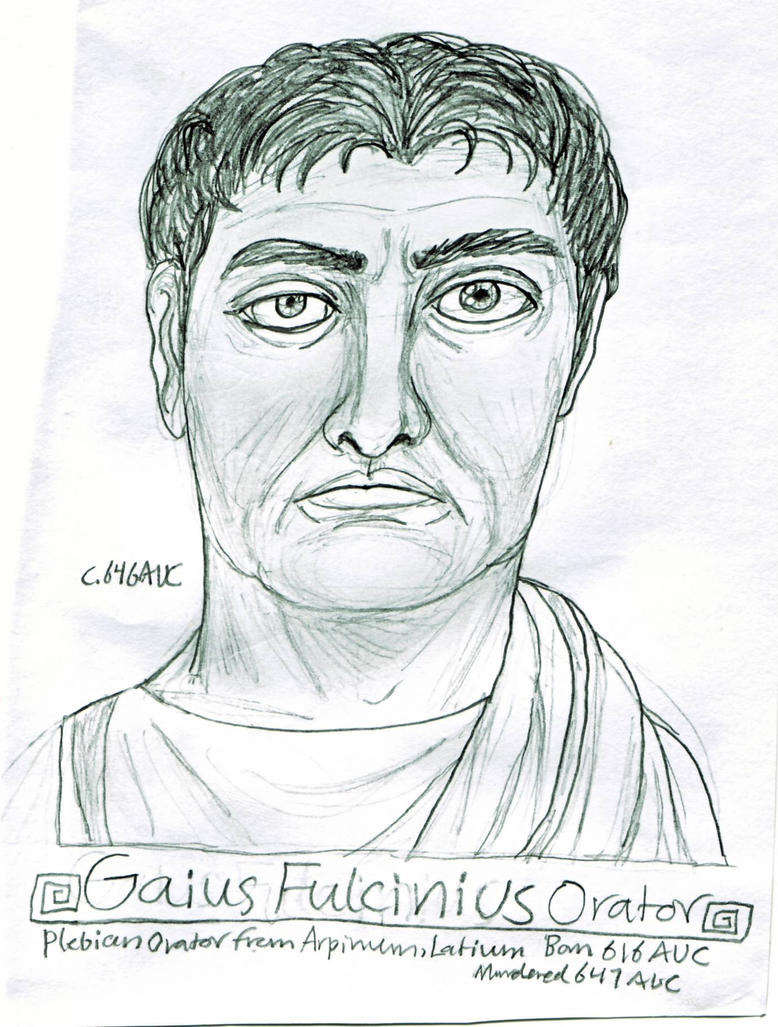

The 23rd day of Quintilis dawned bright and hot and early. The day of shock had passed, and now Rome rose up in indignation. The Senators and their hangers-on had been very uneasy the previous day in the Forum, which had been the day after the Battle in the Forum. Gaius Fulcinius had been giving out that the Senators had wantonly slaughtered a few hundred unarmed, innocent men who had gone to the Forum to keep an eye on things; that the Senators were scheming and planning among themselves to defraud the people of their wealth and their grain was obvious.

The indignation, however, did not rise against the Senators that now formed a solid core around Scaurus--who had relented and adopted Metellus Nepos as his second-in-command in this unofficial conflict. Deplore Nepos's tactics though he might, Scaurus was aware that they were almost necessary; indeed, had Nepos's ex-gladiators not been there to save the day, half the Senate would now lay dead in the lime pits outside the city.

The indignation rose instead against Memmius and Fimbria, and against Fulcinius himself. For months a shut-in, he had grown suspicious to the People of Rome, who now asked themselves: What exactly was it he had done? A grain law and he thinks he's King? And he let Catulus Caesar get away with losing twenty-odd legions? There hadn't bee much mumbling and grumbling before Marcus Antonius death, and even after he had lain low and not drawn attention; then Titus Bruttius had been assassinated. The storm had broken, Gaius Fulcinius put himself in the forefront, and found...that he had lost the love of the Crowd.

That which had been a drug to him during his days condemning Catulus Caesar and toying with men like Lucullus and Scaurus was gone; nor, he thought, could it ever come back. He believed in the innocence of Memmius and Fimbria, but did not much care either way; whether he won or lost, his life had lost all passion and purpose. So he would try to drag the damned Senate as far down with him as possible.

Aware that his plans would hurt Memmius and Fimbria, he did not much care about that either. He simply made preparations...and sprung the trap. Though most men were fairly law-abiding, there were always some thousands in a city of about a million souls who were ready to do the worst evil for gold, or silver, or even a sliver of food. It was to these souls, and not the hard-working hearts of the Fifth Class and Head Count, that Gaius Fulcinius now catered.

The five hundred he had sent yesterday made up about a quarter of the gang members at his disposal, and were the most that he'd every used at once; of all the men who worked for him, he--secretive that he was--only ever met about a hundred. He met about sixty of the most powerful and prolific gang chiefs on the 23rd of Quintilis.

Mostly wiry, dirty men with nondescript features and bristling stubble, some had bright and happy eyes--liking to trick and steal--and others had dull and colorless eyes--the ones he could depend on to torture and terrorize. Some half of them were of the Head Count, but even the Head Count had great enough pride in its citizen status to not wish public violence upon their city; the other half were non-citizen freemen--free immigrants, ex-gladiators, and some stranded sailors from all over the Middle Sea. Though they made up half of Fulcinius's forces, their number in the city was smaller, and so it could actually be said at that time that more non-citizen freemen were for Fulcinius than not--not surprising, since he promised them citizenship, wealth, and enrollment into a rural Tribe instead of a worthless urban one.

Gaius Fulcinius, aware that the end was nigh and willing to do anything to accelerate its approach, told them exactly what to do. The Senate was meeting every day, but Fulcinius would no longer attend. That day he sat atop the Esquiline Hill and watched the beauty unfold.

Gaius Servilius Glaucia, for one, did not plan to be far from the action when it occurred. Since his friend Saturninus's revelation only a little more than a month ago, the world had turned upside-down with the deaths of the Propraetor and the senior Consul. Glaucia, astonished at these upheavals of the established order of things, had yet exercised his right as a Roman; that is, namely, to wait it out and see what advantage he could reap out of the whole affair.

His opinion that Lucius Cassius Longinus Ravilla would be difficult to defeat in the consular elections had been reinforced when Ravilla was awarded a Triumph by the Senate in May; he was said to be marching to Rome--much to the populace's relief--as the situation in the Forum worsened. Now Glaucia--not a Patrician Servilius, of course, but wishing to be no man's client--needed a solid feat of bravery and intelligence, the better to defeat or at least match Ravilla with; one also never knew what latecomer might run for Consul and be, by a fluke of fate, elected.

So he waited and thought, and sat in the background at every meeting of the Senate or stood quietly at the unofficial gatherings of its members in the Forum. He didn't miss Scaurus's fall, or the Battle of the Forum, or the ascendancy of the "Youngbloods" as Scaurus termed the crew of Nepos and Ahenobarbus not unkindly.

Oh, the Youngbloods! When Glaucia was elected, he would have to deal with a multitude of them as Quaestors, and as Tresviri Monetalis--the three young men in their mid-twenties of Senatorial class who supervised the minting of coin, and as Military Tribunes, and as clerks and other unofficial officials. For he knew that if they defeated Fulcinius in this war--it was truly a war, now--they would win a larger portion of the vote in this year's election than the Populists had in last year's. If Gaius Fulcinius won...well, then Glaucia wouldn't have to worry about being Consul; he was too close to their overly-perceptive enemy Saturninus to be safe.

And if the magistracies would be chock-full of Youngbloods and their friends and allies, then why not cultivate them? Glaucia after all had not a Populist bone in his body; he was in this world for himself only, and had only joined them last year to cause a splash as Tribune of the Plebs. Well, he and his mediocre colleagues were being quite outdone by Gaius Fulcinius, so what remained to be done but to find another route to glory?

He ventured out on that morning of the 23rd having already sent his slave out to deliver the request for an audience; the one-word reply was immediate. Come, it said. Apparently the novelty of being visited by a Tribune of the Plebs was too much for Metellus Nepos to resist.

From what he saw of Metellus Nepos, Glaucia was impressed but not tempted at all spiritually; what he saw was a useful alliance with an intelligent person, nothing more. The young man was quite the fanatic for the Senatorial class, and would clearly kill to maintain that class's superiority. Ahenobarbus was a more interesting figure; ostensibly on the side of Senatorial right, certain rumors had said that he'd orchestrated his own acquittal with Fulcinius last year. That he was willing to deal with a man such as Fulcinius indicated that he was more like Glaucia than he seemed: he did things for the aid of himself only.

He entered the spacious, impeccably-decorated house that had belonged to Metellus Balearicus while the sun wasn't too high over the horizon. No spendthrift but also no peasant, Balearicus had chosen a frugal and stylish way to decorate his home; he had taken every precious and valuable Punic and Celtiberian jewel and statue and effigy to be had on the Balearic Islands which he had conquered, and brought them home, along with every other kind of delicacy and artwork. Since the clientship of most of the Baleares had transferred to Nepos on his father's death, he still enjoyed a table covered with the famous cavaticae snails that all gourmands and connoisseurs cherished, and the cheese of Mahon, and that famous olive oil. In his house walls were covered with vivid paintings using pigment of Sinope Earth, and strange and alien potteries and figurines of that same compound. Ancient statues of tin mined on the tin isles past the Pillars of Hercules adorned the plinths around the walls and in the hallways of the home; some of these plinths were the millennia-old cyclopean blocks of the talaioti structures.

Many other fascinating statues and artworks were stored in the basement of the Metellus Nepos house, and would have doubled their owner's wealth had he only cared to look for them. Metellus Nepos, alas, was no lover of art; still, he had so little need for the money that he missed it not at all. He was not a greedy fellow, and such was the impression that he immediately made upon Glaucia, and quite unconsciously.

"Ah, our unusual guest!" he cried unselfconsciously as Glaucia was ushered into the room by the steward. Looking around, he found no room--he liked having open space unhindered by couches unless absolutely needed--and, plucking a priceless tin-and-silver statue from its plinth, chucked it at the steward with little warning. "I need somewhere to sit," he explained cheerfully, and nimbly sat upon the plinth, which left Glaucia with nowhere to sit but the couch his host had just vacated.

Cool Ahenobarbus, with his cool Domitian eyes, inclined his head. "Good morning, Gaius Servilius."

"Good morning," Glaucia nodded back, and formally greeted Metellus Nepos again. Knowing that they were consumed with curiosity, and not one to delay or take pleasure in others' discomfort, Glaucia simply began: "I've come here today as a Senator, my colleagues. What has been happening in the Forum and in the world at large for the past month or so is intolerable."

"I quite agree," said Metellus Nepos, an expression of intensely curious interest on his face.

Glaucia continued, "Of course you do, and I see you as one of the best at trying to rectify it. Your action two days ago saved hundreds of lives--not the least of which was my own! Though violence should be the last resort, some forget that it is a resort, and that it must sometimes be used."

"Excellent, yes, good!" cried Metellus Nepos. "As I've tried explaining to the Boni many times now. So far you're with us...I guess." He shared a private smile with Ahenobarbus.

"Yes, I'm with you," said Glaucia. "Remember--you should know by now, you're in the know about everything--that my great friend Lucius Appuleius was the first to notify Scaurus that something was wrong, only a day before poor Antonius's murder. You know I'm his best friend; he told me everything days before."

"So we can trust you," said Ahenobarbus, arms splayed from where he reclined on his couch perpendicular to Glaucia. "What now?"

"I'll be frank, because you two are frank men and not devious...as far as I can tell," Glaucia added with a devious smile. Ahenobarbus chuckled at that, but Nepos motioned for him to continue. "Any action against the two swindlers and their poor lackey--martial, legal, subterfuge, anything--is action for me. I want to be in the middle of it."

"And then you'll be Consul," said sharp Nepos, hand rolling in midair. "What's in it for us?"

"When we win, you two will be heroes. You'll both be elected at the top of the polls no matter what you run for. You, Quintus Caecilius, will obviously be Quaestor; I imagine that Gnaeus Domitius will want Gaius Fulcinius's current post--that is, his official post. When I am Consul and you two in your offices, we will work together; you'll face no obstruction from me, I promise you that, and I hope that you don't do anything to discredit me...or to piss me off."

"Not that you could ever do much about it," grinned Nepos nastily, remind Glaucia who held greater power at the moment. "You had better be true to your word, Gaius Servilius; if you do veto us--well, me; you can't veto a Tribune of the Plebs as Consul--at any moment next year, you will be very sorry for it."

"Of that I am well aware, Quintus Caecilius," said Glaucia, not grinning at all. After a pause he said, "I do really hope that the battle is a legal one; the Tribunes of the Plebs being sacrosanct, and too much sacrilege and misfortune having happened this year, I shudder to think what the murder of a Tribune of the Plebs might bring."

"All politics, Gaius Servilius!" said Ahenobarbus brightly. "It's only politics."

tuareg109

Banned

FOR WANT OF THE HAMMER

THE FIRST GREAT GRAIN ROBBERY PART 8, 647 AVC

THE FIRST GREAT GRAIN ROBBERY PART 8, 647 AVC

"Are we ready?" asked Metellus Nepos in that carrying voice of his. Not that it needed to carry, seeing as the entire group was in the Curia Hostilia; his voice bounced off the walls and the closed double bronze doors, and came to every ear. The men, who had been checking and re-checking their gear and equipment for hours now, sprang up enthusiastically.

It was the 25th of Quintilis, and every Senator who could be contacted and trusted now knew that the time was ripe for action. Glaucia had in fact been one of those completely prepared to visit the Forum on the 23rd, after he visited Nepos and Ahenobarbus, and to wait for whatever situation might arise; Metellus Nepos, with his contacts and underground web, had dissuaded him. He'd only said that "something big" would happen, and he'd been right.

Glaucia had stayed as a guest in the fine house on the Palatine until sometime before noon on that day, the 23rd, when they moved to the house of Ahenobarbus. Only the Marcus Livius Drusus house had a better view of the Forum, and no Ahenobarbus was too welcome there these days; in return, Drusus was not invited to the Ahenobarbus house. Neither was Ahenobarbus's brother Lucius Pontiff. The house's terrace, which stood in "front" and faced the Forum, was above the house and stood some thirty or forty feet above the floor of the Forum only a few hundred feet away; it truly provided the ideal view. Here Ahenobarbus took his guests--Metellus Nepos, Glaucia, Scaurus Junior, Nepos's brothers-in-law the two Licinii Crassi, Lucius Julius Caesar, his blood brother Catulus Caesar, his brother-in-law Quintus Servilius Caepio Senior, his brother Gnaeus, Nepos's cousins the Metelli Caprarilli, the brothers Valerii, Gnaeus Pompeius Strabo, Lucius Cassius Longinus Junior, a few other younger Senators and Senators' sons, and--surprise to all of them but Ahenobarbus--Spurius Dellius.

Now 52 years old and glowing with vitality and youth, Spurius Dellius still had about twenty years on most of the men present; the next-oldest men, Catulus Caesar and Caepio, were nine years younger than he--Glaucia was two years behind them. He'd been married to Julia for little more than a month, and the novelty of married life hadn't worn out; in fact, he thought that it never would! Every day he came home from days at his tribunal--eventful or boring, violent or calm--brightened when he saw her smile and felt her kisses and smelled the flowers that she still gathered with her mother; before her his ambition had had no direction or purpose, now he knew that it was all for her, and the half-Julian child that would soon be growing in her. She was not pregnant yet--or it hadn't showed after only a month--but she would be soon! If the strength of Spurius Dellius and the couple's enthusiasm were anything to go by, the child would indeed be growing soon.

There was very little breeze that day, so Ahenobarbus ordered his slaves to unravel the tent-cloth that was attached to 20-foot poles at intervals along the edge of the terrace; this provided shade for the watchers. Comfortable in the warm, dry shade and drinking for the most part very diluted wine, the watchers mingled and conversed.

Spurius Dellius wandered around until he saw Catulus Caesar and Caepio standing at the edge of the blob formed by the group, looking uncomfortable; both men were sticklers for tradition and authority, and both deplored yet viewed as necessary the tactics that Metellus Nepos and his like employed. Spurius Dellius slid up to them and said, "Good morning Quintus Lutatius, Quintus Servilius." After they mumbled greetings of their own, he continued, "How is Caninia coping with Marcus Antonius's death, now that it's been quite some time? She looked well even when she visited my tribunal with your wife about half a month ago."

"Why would she visit your tribunal?" asked Catulus Caesar suspiciously, suspicious man that he was.

"Oh, they were just taking a stroll," said Spurius Dellius, brows raised.

Caepio, who had grown up not nearly as jealous of women, rolled his eyes at his brother-in-law. "Don't worry, Quintus Lutatius! My sister's a pain when it comes to the Forum; can't be stopped from going, even for the most important of functions!"

"I put a stop to that!" said Catulus Caesar harshly. "She wanted to go shopping on the day my son put on the toga virilis and became a man; can you believe that?"

Caepio shook his head and said, "I must apologize for my father's sake, Quintus Lutatius. We allowed her to be a bit too free; still, I do not like broken and spiritless women. Just look at Drusus's daughter! Poor thing."

Catulus Caesar shrugged. "I thank you for the apology, and agree with you about Livia Drusa. The Caesars are always stern yet fair; you both know the old adage about Julias always making their men happy. Well I, as a Lutatius Catulus, will try to make that true for my family."

Spurius Dellius had chuckled at Catulus Caesar's adage, and said with feeling, "Oh, how true that is, Quintus Lutatius! Now that a Julia loves me, I feel as though I could walk through walls!"

"Good for you," said Catulus Caesar pleasantly enough, though personally he thought that allowing a New Man like Spurius Dellius to marry a Julia was to make a mockery of the Patriciate, and of the institution of marriage.

A few hours passed in this way, until Quintus Caecilius Metellus Caprarillus cried out, "Look!" as the day was passing from noon into afternoon. The men moved forward and crowded to the edge of the terrace; there, down in the Forum! From three directions--for Ahenobarbus's house afforded quite the excellent view--a crowd of seething, club-wielding men came at a jog. It looked as though the Argiletum, the Via Sacra, and the wide space that was the lower Forum coming up from the Velabrum were full of ants crowding toward the rostra and the Senate house.

Forum frequenters and stray Senators and Knights scattered left and right and into buildings and a few even onto roofs as this host poured into the Forum from three directions. The slower and unlucky few were seized and pushed about; those who protested loudly or cursed were beaten quickly with the clubs. They were dispassionate beatings; once the victim was senseless, he was dropped then and there and left untrampled and alive. The few that were close enough to the Clivus Capitolinus ran up to barricade themselves in the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus; they were not pursued.

Quintus Accius, President of the Guild of Lictors, would not run to barricade himself anywhere. He led about 50 other Lictors out of their headquarters near the Senate House and they began to beat the crowd, using their fasces as clubs. However, 50 were no match against 1,000; they were surrounded and beaten senseless. Quintus Accius alone died.

The Senators on Ahenobarbus's terrace watched open-mouthed as the Comitia Well was filled; however, when viewed in the open space of the Forum, the mass at least seemed smaller. There were perhaps a thousand men gathered; what made them dangerous was their willingness--and indeed their determination--to do violence.

"And now," said Metellus Nepos sarcastically, "you can all appreciate the need for violence." Heads nodded absently, absorbed in the spectacle below. The Forum Romanum belonged to Gaius Fulcinius, and the First and Second Classes had not the numbers to retake it.

The first two Classes had not the numbers, but they had the quality.

"Are we ready?" asked Metellus Nepos two days later, and the men stood up to his command. The Senate House, meant to accommodate 300 Senators and their servants, as well as a few clerks, held five hundred armed men quite easily. The Curia was not quite roomy, but a man could spin in a circle with his arms outstretched and touch no other.

"Then let's go." After the invasion of two days ago, Metellus Nepos had simply kept in contact with his people, and learned of what would happen today. Communication was unhindered, as the Forum invaders hadn't bothered to take the Palatine or the Capitol; it was the Forum, political center that it was, that they needed. Without the Forum, the Senate could do nothing.

Or so the invaders thought. While the gangs slept on those warm flagstones and waited and patrolled under the sun, Metellus Nepos received his news with regularity, and he knew; Gaius Fulcinius would speak from the rostra at about noon to promulgate several new laws--citizenship and rural tribes for his non-citizen supporters; membership in a new, Popular Senate for all of them; ten iugera of good land for every Roman and one hundred for the supporters; grain would cost one sestertius per the modius instead of the current five; and more. Since the Plebeian Assembly was tribal in nature, Gaius Fulcinius technically only needed 35 men--one from each tribe. This he accomplished with ease, by sifting through his supporters and--when no man could be found of a certain tribe--by abducting a man and slapping him about until he agreed to vote.

It was about noon in the Curia Hostilia, and a small, fleet slave hidden behind the Curia had indicated that Gaius Fulcinius was now on the rostra. It was time. The bronze doors of the Senate house were opened slowly and without sound--they had been smeared with grease the night before--and the 500 or so supporters of the Senate filed out. They had been in the shade, well-rested and well-watered all day; Gaius Fulcinius's men had been standing, sometimes thirsty, under the hot sun all day. Also, they had the element of surprise, for Gaius Fulcinius faced away from the Senate House, and his men had eyes only for him; the men facing the Senate House would in any case be gazing adoringly up at him.

Methodically and without panic, the Senators and their supporters set a table up on the small Senate portico, just above the steps. They dragged out the bags full of heavy stones and set them up by the stairs, and those strongest among them took up the spears and ringed themselves at the top of the Senate steps, in front of the table and stones, and facing out, toward the Forum. There they sat at ease, waiting, every man trusting the planning of Metellus Nepos with his life.

Gaius Fulcinius spoke, and spoke. He extolled the virtues--such as they were--of the men assembled before him, and of their bravery and their virtue. He spoke of the legal order of things, and of assemblies and votes weighted against certain people--specifically those arrayed before him, and of the need for a vote. He detailed every measure of his Lex Fulcinia de civitas, extending the citizenship to his supporters. Then he said the magic words, majestically. Gesturing to the 21 smiling and the 14 ruffled isolated men in the deep Well of the Comitia, he said loudly, "Let the voting commence!"

"VETO!" roared Tribune of the Plebs Gaius Servilius Glaucia from atop the table. Deep and loud and regal in the silence following Fulcinius's demand, thin and reedy by comparison, it caused an immediate stir; men turned their heads to look, and those in the Well of the Comitia scrambled up the circular steps that made up its sides in order to see above its rim. The silence was extended; all waited to see what Gaius Fulcinius would say.

The legal way was over for him. If he did not accept Glaucia's Veto--which he could not; the crowd would tear him apart--then he was impeding a Tribune of the Plebs in his duty, and could legally be thrown off the Tarpeian Rock as a traitor. His men would never do it of course, but it did not matter; the legal way of doing things was over. "No!" he shouted back. "I Veto you, Glaucia, boot-licking scum that you are. The Plebs elected you to protect their interests, and not the Senate's! Scum! Scum!"

His men took up the chant of "Scum!", and began to advance on the Curia Hostilia. But the Senators and supporters were ready. Sharp, heavy rocks began to fly before the rabble was in range, and many were struck down before the throwers even had time to get used to throwing, and to get good at it. They chucked harder and harder, striking brows and eyes and shoulders everywhere; some fell, and many fell back, hindering and slowing their friends.

Still, there were 300 throwers but about 1,000 opponents, and not all could be struck at once. The gangs were faltering, but they still advanced up the Senate steps--straight into the spears of those biggest and burliest men. Tall, strong Spurius Dellius was one of them; though he did not enjoy burying his spearhead in this man's guts or that man's thigh, he had been a soldier for long enough to be completely removed from it emotionally. Rome was Rome, and she required sacrifices.

The crowd broke when Glaucia--who had a bag of stones for himself and was throwing after his proclamation of Veto--flicked a superbly-aimed stone at Gaius Fulcinius, whose brow was suddenly covered in blood and who toppled down into the Well of the Comitia, and onto the 35 hapless electors. Unluckily for the Senators, he was alive, and was half-walking half-carried out of the Forum at a run, with the spearmen in hot pursuit. However, there were three ways for the rabble to split up, and only 200 spearmen; they decided to stick together and go after Gaius Fulcinius, up the Via Sacra and into the Subura.

They gave up their pursuit after encountering the eerie alleys and quiet streets of that usually busy district, but not after seeing some citizens chucking stone blocks and blocks of firewood down at the fleeing rabble, and desisting when the spearmen ran past. It seemed as though the sacrilegious killing of a Lictor two days ago--which had spread through the city like wildfire; a third nefas killing in two months!--had not endeared Gaius Fulcinius, Memmius, and Fimbria to the people of Rome.

The spearmen jogged back to the Forum victorious, having lost no man of their number, and having killed about 100 rabble, seriously wounded 300--who would be crucified if not Roman, and hurled of the Tarpeian Rock if they were, and wounded almost every man who had gone home running. Yes, things were looking up for the Senate.

Glaucia's name was on every man's lips that day, for his Veto and for his lucky throw. Yes, things looked up for Glaucia as well.

Last edited:

Need any help with that?

Aaaand that's being planned as I write; I've only planned to mid-October, after all.

tuareg109

Banned

Need any help with that?

I doubt anybody could help or improve my excellent writing! As for planning; no, I think I've got it under control. It's just that I don't want to get ahead of myself. After all, when I write a full sheet (about 4-6 months) of dates and events, I only get halfway through before I have to start on another, because of how obsolete the second half is.

For example, I had originally planned for Marcus Antonius to survive, and to be elected Consul. I also had Catulus Caesar being solidly convicted at one point.

Last edited:

tuareg109

Banned

FOR WANT OF THE HAMMER

SETTLING ACCOUNTS, 647 AVC

SETTLING ACCOUNTS, 647 AVC

Peace reigned, paradoxically, for the next three days. The Senators and their supporters and Metellus Nepos's ex-gladiators and ex-centurions and the Lictors were vigilant and strategic enough to hold the Forum, and to organize their own gangs made up of upper-class youth and aspiring athletes to guard the Palatine and the wealthier neighborhoods of the Velia, the Carinae, and the Oppian, Esquiline, Viminal, and Quirinal Hills.

The gangs of Gaius Fulcinius, now limited to the Subura, did not dare run around looting. The patriotic Romans--which meant almost all Romans--were sick of the public violence, and would indeed quite enjoy lynching politically-motivated troublemakers on sight. Gaius Fulcinius planned and planned on how to get his power and the love of the People back, but he just could not find a way; Gaius Memmius and Gaius Flavius Fimbria were out of their minds with terror. They had never thought it would go this far.

They sat in the rented ground-floor apartment of a large insula in the heart of the Subura. Nobody but their most important gang leaders even knew that it was they who lived there, and their meetings were few and far enough in between to avoid arousing any suspicion. Across from the peristyle-garden from them lived a nondescript, politically uninvolved plutocrat Knight-businessman who asked no questions, and who indeed was not at home for most of the year. His wife had made several subtle advances toward the handsome Gaius Memmius who, penis shriveled with fear, naturally declined; if because of her the other residents thought they were homosexuals, so what? It would only decrease any desire to ask questions or get close.

It was on the fourth day after the Second Battle of the Forum, the 29th of Quintilis, that four of their major gang leaders came to see them, somewhat unexpectedly. "Ah, is there news? Good news, I hope!" said Gaius Fulcinius, who was growing his stubble out again after having had to shave for his failed legislative appearance.

Numerius Victicus--a very strange name!--was the nominal leaders of the confederacy of gangs that worked for and reported to Gaius Fulcinius. He was a tall, narrow but not skinny man with long legs and long arms, who always seemed to be ready to pounce. He was about forty years old or somewhere thereabouts; wiry brown hair flecked with grey linked around his face with a beard of the same hue, which covered and accentuated his pleasantly simian face. His wide lips were, when neutral, always forming a strange smile that raised his lips' ends and centers, but lowered their mid-sides. His looks lent themselves to humor and to jollity, which made him all the more dangerous in his line of work.

Numerius Victicus threw a long leg over the side of the empty couch and sat down upon it in this way, always ready for action. "Hmm, some news; not too good," he said as the other three leaders moved around and looked about, especially toward the perisyleum behind the reclining housemates.

Gaius Fulcinius started, hissed; Memmius and Fimbria reared up, staring at him. In the last few days this strange behavior, especially at the mention of setbacks or mistakes, had become more common. It unnerved them immensely. Numerius Victicus, for his part, was not unnerved; he gazed curiously at Gaius Fulcinius, with one eyebrow raised. "Please continue," sighed Memmius.

"Well," said Numerius, jerking his limbs and looking lively, "I've just discovered that men have begun deserting from our cause; what's more is that we can't punish most of them, as the Suburans jump on us--they've killed thirteen men!--when we try. This emboldens more deserters and traitors; I've heard talk that there are even some gang leaders who are in Metellus's pay."

"That damned man!" shouted Gaius Fulcinius at the top of his lungs. The six observers of this yell heard the sounds outside in the street stop for a few seconds, and then resume slowly.

"Yes," said Memmius gently, always having to defuse the situation--though he had caused most of it. "Yes, my friend, that man belongs in Hades."

Numerius shrugged, "Each man belongs where he ends up," he said sagely, and unhelpfully.

Memmius scowled, annoyed at the man's fatalism. "So we belong here, cooped up in this insula while the Senate owns the Forum?" he snapped sarcastically.

A subtle change came over Numerius as he said "Yes", and Memmius stood quickly, so that the sword of one of the gang members didn't even have to strike down into the vulnerable meat above his collarbone. His shriek became a strangled gurgle, and was the loudest cry any of the three of them had made.

When it was done, and with no witness in the form of steward or slave or servant, the four gang leaders stepped over and around the three still bodies. "Let's go," said Numerius. "Enough of this."

Later that day, after the news had been confirmed throughout Rome and Senators walked unmolested from the Quirinal to the Capitol, Numerius had his pay. "Keep yourself in Rome, Numerius Victicus; I suspect I'll be needing you soon," said Metellus Nepos.

The man gave a grinning salute, lifting the bag of gold that was his pay to eye height before letting it sag to the ground. "Oh, so much!" he grinned at Metellus Nepos. "And I'm no weedy weakling! Rest assured, Quintus Caecilius, that I will stay in the neighborhood." With another salute, this time sans gold, Numerius departed for parts unknown.

"And that," said Metellus Nepos as he turned to Ahenobarbus, "is that." Numerius had just exited his study, which was clean and uncluttered, in contrast to its state during the previous few weeks. His cleaning servants would be so grateful to have a clear desk to clean again, instead of a paper-strewn, occupied war room.

"That's that!" paraphrased Ahenobarbus with a grin. "Splendidly accomplished, Quintus dear. Your role in all this will come out; you'll come in as the top-polling Quaestor, I'm sure of it."

"Oh hush," lisped Metellus Nepos in mock-modesty, and the two collapsed into giggles, giddy with victory. Metellus Nepos, as honest? AHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHHAHAHAHAH!

"So, what else do you plan on doing?" asked Ahenobarbus, recovering slowly from that spasm of laughs.

"Oh, I know what I have to do with my newfound fame!" cried Metellus Nepos. "I must marry Aurelia Cotta!"

Ahenobarbus took a slow, long sip from his wine cup and ruminated on this. Finally he set the cup down and said with straight face and gleaming eye, "I don't think she'll have you, Quintus."

"Oh shut up Gnaeus you bastard!" shouted Metellus Nepos, draining his own cup and throwing it at Ahenobarbus--aiming to miss, of course. Which he did; the cup glanced off of Ahenobarbus's toga and skittered on the floor, only to land exactly facing down in the Atrium pool. Both men were consumed with laughter after that, and it took many minutes for them to calm down.

The crisis was over.

OR WAS IT? DUN DUN DUNNNN!

Well, this particular crisis may be over, but I'm sure the Boni and the Populares will find new and ingenious ways to cock up Rome's domestic political situation. Which, knowing your sympathies, will allow Sulla to become dictator or two-centuries-earlier Octavian or some business.

Hope the crisis is over, at least. I do note that this last update lacked the Great Grain Robbery appellation, which would, in any case, indicate the end of the Memmius-Fimbra-Fulcinius fraca. Glad to see their unholy triumvirate laid low.

Hope the crisis is over, at least. I do note that this last update lacked the Great Grain Robbery appellation, which would, in any case, indicate the end of the Memmius-Fimbra-Fulcinius fraca. Glad to see their unholy triumvirate laid low.

tuareg109

Banned

Oh certainly, of course. It's not called "The Crisis of the Roman Republic" for no reason, after all. As for Sulla, he has his own flaws; his support base isn't broad and varied enough for him to become any sort of Augustus-figure (Father of Rome, Savior of the State, etc.).

Yes, but at the end of the day I still feel sort of sorry for Gaius Fulcinius. A fluke in the weather, the bully-boy tactics of Metellus Nepos, and thus his impossible loss of what was a sure case caused the mental deterioration that led to his believing the charming Memmius and tag-along Fimbria.

Remember that Fimbria's son--historically an utterly disgusting and unscrupulous character--also exists in this TL, as he was in OTL, as he is old enough to avoid any butterflies. Though, since he is young and intellectually unformed, the disgrace of his father might push him to become a hard-line Constitutionalist and anti-corruption fanatic (if there is such a thing as being too much against corruption).

Also I think Memmius had a son (or, more important politically, grandson?)...I'll have to see.

Then there's the Marcus Aemilius Lepidus (14 years old now) who married Saturninus's daughter Appuleia (about 4 years old now); they're the parents of THE Lepidus. I'll have to see if I can set that up. I'm not normally convergent at all, so I'll see what happens/what I cook up.

Yes, but at the end of the day I still feel sort of sorry for Gaius Fulcinius. A fluke in the weather, the bully-boy tactics of Metellus Nepos, and thus his impossible loss of what was a sure case caused the mental deterioration that led to his believing the charming Memmius and tag-along Fimbria.

Remember that Fimbria's son--historically an utterly disgusting and unscrupulous character--also exists in this TL, as he was in OTL, as he is old enough to avoid any butterflies. Though, since he is young and intellectually unformed, the disgrace of his father might push him to become a hard-line Constitutionalist and anti-corruption fanatic (if there is such a thing as being too much against corruption).

Also I think Memmius had a son (or, more important politically, grandson?)...I'll have to see.

Then there's the Marcus Aemilius Lepidus (14 years old now) who married Saturninus's daughter Appuleia (about 4 years old now); they're the parents of THE Lepidus. I'll have to see if I can set that up. I'm not normally convergent at all, so I'll see what happens/what I cook up.

tuareg109

Banned

Aren't we forgetting somebody?

Hold on, hold on! The Germans can't take over/become noticeable in Spain in only a month (which is the timespan of the last 10 updates!). Remember also that it takes two weeks to a month for communication from Spain to Rome.

tuareg109

Banned

FOR WANT OF THE HAMMER

DIVERSIONS PART 5, 647 AVC

DIVERSIONS PART 5, 647 AVC

"Oh!" groaned Lucius Cassius Longinus Ravilla, stretching his hairy arms over his head. "Oh, it's good to be home after so long on the road!" The sun had just barely peeked over the horizon, but his men were already poking their heads out of their tents and stumbling out into the warm air to relieve themselves and to begin the day. He had arrived the night before, and camped on the Campus Martius, as every Triumphing general did; messages had been sent to the city's leaders, merely to inform them that he had arrived.

Now they stood in front of him--Scaurus and Lucius Pontifex Maximus only; quite the meager homecoming committee. "It's great to see you home, Lucius Cassius," said Lucius Caecilius Metellus Pontifex Maximus, smiling widely. "I thought you'd never come home!"

"Well, I profess that I was going to take my time; then I heard of events in Rome! How are you holding up against Gaius Fulcinius?"

Scaurus laughed uneasily--he didn't laugh very easily these days--and said, "Oh, we should've sent a letter. Gaius Fulcinius and his co-conspirators were killed--assassinated, I presume, by their gang leaders."

Ravilla's eyes widened. "That is excellent news. I was beginning to think that we would have to bring soldiers inside of Rome; not that that hasn't happened already, right?" he added slyly.

Scaurus looked uncomfortable. "The Senate was attacked, and the Senate defended itself. You, being a Senator, should understand that."

"Of course, of course!" Internally, however, Longinus Ravilla couldn't quite condone such a use of force in the Forum, or within the city's sacred Pomerium. "However, the gang leaders still murdered three Senators, one of whom was an inaugurated Tribune of the Plebs; Tribunes are sacrosanct, and these murderers should be hunted down."

Lucius Pontifex Maximus, who had something of a hunch that the blessed end to public violence had something to do with his cousin's son Metellus Nepos, pretended ignorance and said, "The Urban Praetor is working day and night to find them, and to find other men involved. He's questioning people all over the Subura, asking whether they know anyone who's been absent from work or common life in the past few weeks. Any man who has...well, he's probably one of the Forum rabble."

"Good thinking," said Ravilla, nodding. "Spurius Dellius always seemed a very capable man to me; I'm sure he'll catch the murderers." After a brief silence that Ravilla allowed for any input, he asked, "By the way, has a specific date been set for my Triumph? I want to walk free in the city, and I should start on my election campaign as soon as possible."

"Ah, excellent! You will be Consul, Lucius Cassius, I know it!" said Scaurus jubilantly; here was one man he could wholeheartedly support.

"But not," said Ravilla shrewdly, "senior Consul, right? I've heard of Gaius Servilius Glaucia's exploits; I can say, though, that he quite deserves the top spot! Though I do hope my friend Marcus Aurelius Cotta manages to beat him," he added hopefully.

Scaurus grimaced. "The man is certainly brave, and capable, but I can't say that he's as qualified as you are. He was elected in this year with all those Populists, after all!"

Ravilla shook his head. "I don't think he was with them, I think he ran for Tribune of the Plebs for the hell of it, to fill in a year between being Propraetor and Consul, and to collect some fame and renown. He's done it, for sure."

"Oh, any Tribune could have Vetoed like he did!" snapped Scaurus disdainfully. "Nothing special!"

"Every other Tribune," grinned Ravilla, "is a friend of Gaius Fulcinius's, and probably a wretched coward besides. No, Marcus Aemilius, you must give credit where credit is due."

Scaurus subsided, and it was Lucius Pontifex Maximus who continued, "Speaking of which, what's Quintus Servilius Caepio Junior to be credited with when he comes home? I hope you don't go back to your province to find it burning."

Ravilla snorted. "You leading lights are such...backstabbers! Caepio is one of your most solid comrades, but his son is beneath your dignity."

"We do what's best for Rome," said Lucius Pontifex Maximus with a snort of his own.

That set Ravilla laughing. "Okay, okay; the young man's in charge, but I don't think there's a man there who likes him. They wouldn't follow him to an exotic whorehouse, let alone into the woods and mountains of wild Macedonia."

"Oh, good! No Catulus Caesar-like blunder in Macedonia; that would set us back ten years or more," reacted Lucius Pontifex Maximus.

That set Ravilla to laughing yet again. "Oh, oh, oh! Bitter about that, are we? The letters I got--what a hoot! I take it you two think he should have been convicted?"

Scaurus answered, growling, "In a way. A huge fine would have been in order, but Gaius Fulcinius wanted to basically lynch the man; we had to argue for acquittal, you see."

"I see, I see," said Ravilla, still chuckling. "I wonder, though, how Quintus Lutatius himself feels about this whole business? Is he floating on air at the apparently divine retribution against every man who was set permanently against him? Marcus Antonius dead, Titus Bruttius dead, Lucius Vettius revealed as something of a coward, Gaius Fulcinius dead...I'm sure Memmius and Fimbria are there for some reason or other as well."

"That is not how the gods work, Lucius Cassius!" cried Lucius Pontifex Maximus, immediately angry and indignant. "The spirit of Quirinus would never allow the other gods to visit such disproportionate retribution upon elected officials!"

"All right, all right," said Ravilla, backing down quickly. The anger of Lucius Pontifex Maximus was always a shock after his universally placid and pleasant demeanor. To fill the silence, during which Scaurus beamed happily, Ravilla said, "Speaking of the Germans who beat Catulus Caesar, do we have any news from Publius Rutilius in Gallia?"

"Oh, do we!" hooted Scaurus, clean beaming smile becoming a grin. "The Germans have for the most part moved over the Pyrenees; they're in Hispania Citerior now!"

"Oh dear, does Marcus Aurelius have a war on his hands! What a good way to ride into the Consulship."

Scaurus's smile fell and he shook his head. "Oh, this will be bad news for you, then. He left his province before he knew of the Germans' advent; he's on his way here as we speak."

Oh, that was a terrible blow! Marcus Aurelius could be slandered with cowardice and dereliction of duty, and he wouldn't win the Consulship. "How fate conspires against us," said Lucius Cassius, shaking his head. "Well, how is Publius Rutilius faring otherwise?"

Publius Rutilius Rufus was faring rather well, about a week later. Though the news that the Germans had crossed the Pyrenees into Hispania was something of a blow, it by no means ended his diplomatic duties. The Aquitanian Gauls were very grateful for Sulla's actions against the Germans, and allowed the Romans to make trading and cultural inroads into their lands; the Comatan Gauls, happy that Gnaeus Pompeius Strabo had put an end to the vicious raids of the wild Massif Central tribes, were more apt to lend an ear to Rome's opinions, and to use the governor as a mediator in disputes. Which earned Publius Rutilius many friends.

Still, Publius Rutilius couldn't shake himself of the feeling that Sulla had deliberately failed to inform him of the Germans' movements. Nothing in his behavior had changed, but Publius Rutilius still suspected....

Ah, there he was just now! His milky-white skin still stood out brilliantly against the worn brown leather of his cuirass and accouterments. Both of these items--skin and useful cuirass--clashed with his scarlet Legate's cape and his scarlet sash of imperium. In his right hand was a letter--a letter! Publius Rutilius, natural gossip, was always starved of information--and in his left was the big floppy hat he wore everywhere to protect himself from the sun and to mark himself out to his men.

"Publius Rutilius, I have a letter from Rome!"

"Excellent, excellent! I haven't had a letter from anybody in Rome in almost a month; most unusual!" Publius Rutilius moved to Sulla's side as the letter was being opened. Both of them slowly sagged into the chairs in the general's tent as they read. When they were done, Sulla folded it up slowly and almost reverently.

"Edepol!" shouted Publius Rutilius, grabbing the letter and re-reading.

This mild profanity in response to such a huge mess tested Sulla's sense of appropriateness, and found it wanting; he broke into gales of laughter. "Aha, Publius Rutilius, what a mild insult! I say What the fuck! What in the name of Hades and all the gods is going on in Rome? A Propraetor killed, a Consul assassinated in the city, Marcus Aemilius Scaurus belittled by men not fit to lick his gardener's slave's feet!"

"This is horrible," croaked Publius Rutilius, dejected. Slowly, he set the letter on his desk. "Drusus!" he hollered; the young man, on guard duty, came in quickly.

"Sir," he said, presenting himself. He betrayed no surprise at seeing both men sitting and looking so anxious.

"Call the other Legates and Military Tribunes here; we must have a conference." The men were gathered within ten minutes; Publius Rutilius Rufus, Lucius Cornelius Sulla, Marcus Livius Drusus, Gaius Julius Caesar Strabo Vopiscus, Gnaeus Octavius Ruso, Marcus Antonius Gallus, Gaius Atilius Serranus, Gnaeus Mallius, and several others, all with a vested interest in Rome. When the situation was explained, the governor was bombarded with curses and murmurs and cries of anger and sadness.

"What can we do; everything's falling apart!" cried Gaius Atilius Serranus.

Lucius Cornelius Sulla, quite unable to fathom at times how this man had ever managed to succeed in being elected Praetor, snapped, "Do shut up, you old woman! Rome has faced worse in her time; Lars Porsenna, the Great Samnite War, the Second Punic War, the idiocies of the Brothers Gracchi. Rome will survive, she always has; it's our duty to make sure that she survives the right way."

"So what are we to do, Lucius Cornelius?" asked Quintus Caecilius Metellus the Piglet. He was Sulla's protege now, and could be depended upon to ask such questions, meaning the questions that allowed Sulla to detail what should be done.

"I, for one, won't hesitate. With your permission, Sir," he said to Publius Rutilius, "I would like to depart for Rome, to aid the Senate against this ludicrous uprising. It's been almost three weeks since this letter was sent, so it might all be over; in case it is not, I would like to be as close as possible to the action."

"I agree," said Publius Rutilius, nodding. "In fact, I think we should all go. The danger from the Germans is over here in Gallia Provincia, and we can be of much more use politically and physically in Rome. Marcus Antonius Gallus, I leave you as Deputy-Governor here in Gallia Narbonensis until the Senate should choose to send a replacement.

Marcus Antonius Gallus nodded solemnly, but inside he was jubilant. He was Sulla's man through and through, and knew that, without Sulla, he wouldn't be Deputy-Governor; in fact, he probably wouldn't even be a Legate. Any other aristocratic Roman would have put him under the command of Drusus Junior or Caesar Strabo, and humiliated him in that way; Who are you, that would have indicated, you worm, to want to command a legion in service to Rome?

Well, Sulla wasn't the typical aristocrat, and tall, handsome, capable Marcus Antonius Gallus was no worm. As the party of thirty men including Governor, Legates, Military Tribunes, Lictors, clerks, and best centurions departed, Marcus Antonius Gallus was left with twelve legions of excellent veteran troops.

tuareg109

Banned

FOR WANT OF THE HAMMER

ROMA ET ITALIA PART 9, 647 AVC

ROMA ET ITALIA PART 9, 647 AVC

"Spurius Dellius, I haven't seen you since that day of the 23rd, when the rabble occupied the Forum. You're looking wickedly fit!" Metellus Nepos was sitting on the rooftop terrace of Ahenobarbus's ornate house. As it was early morning, the shadow of the Palatine Hill still covered about half of the terrace, so he and Spurius Dellius had some refuge from the midsummer heat.

"Why thank you, Quintus Caecilius," said Dellius with a wry smile of his own. "I daresay I should feel fit, with all the running around I've been doing in the past week."

"Mmm," said Metellus Nepos, motioning for Dellius to join him in leaning on the balustrade and taking in the magnificent view over the Forum. "Gnaeus Domitius's father was so shrewd in purchasing this house."

Spurius Dellius chuckled, "I still imagine that Marcus Livius Drusus was somewhat quicker."

Nepos's face turned sour. "A more jealous man would have hated Drusus for it, but the late and great Ahenobarbus was his best friend. Still, I'm glad that my friend has the sense not to be Drusus's."

"Though it was really Drusus who wouldn't have him," said Spurius Dellius tactlessly. In fact, he wanted to get his conversational partner riled up.

His quarry didn't quite take the bait. "More idiot Drusus," Nepos said in a matter-of-fact voice. "Gnaeus Domitius only worked for Rome, and Drusus thought him violent and--how did he put it?--unconstitutional for it!" Nepos scoffed, "I ask you!" He turned to Dellius smoothly and said, "Well, now that I think about it, I do ask you. What do you have to ask of me?"

"On to the official business, then. Quintus Caecilius, I'm gathering evidence that could lead to the arrest and trial of anybody connected to the murder of three Senators. To be blunt, we all know that Fulcinius, Memmius, and Fimbria were traitors, but the fact stands that they weren't tried in a court of law; in fact, Gaius Fulcinius couldn't be tried during his term in office. So they were Roman citizens--and Senators besides--who were murdered; that warrants action."

One of Nepos's thin black eyebrows went up. "I would have thought everybody grateful for the end to public strife."

It was Spurius Dellius's turn to raise an eyebrow. "Murder is public strife, Quintus Caecilius, and worse than simple violence. These men were Senators."

"They were rogue villains, and elected by those idiots of the lower classes," snapped Nepos, though his face remained eerily calm. "In any case," he relented wearily, voice calm again, "I know nothing."

"And those two hundred men you had hired in the Velabrum? To be blunt, I would prosecute you myself if your foresight hadn't saved the lives of most of the Senate."

Nepos's eyes narrowed and he said, "Why thank you, Urban Praetor, for letting me know never to trust you!"

Spurius Dellius, seeing that the interview was going south quickly, said, "I apologize. Your foresight was useful." When Nepos didn't answer, he went on, "In any case, the landlord and the other tenants of that insula where the three...men in question lived out their last few days know nothing; the men coming and going were nondescript, and visited infrequently. If there's anything you know, I'd be grateful."

Not wishing to give this unimpressive New Man any information but knowing full well that seeming ignorant would be suspicious, Metellus Nepos sighed. "Though I know little from the traitors' side of things, I do still have clients in the Subura; I'm sure others do too, but I probably know the name of one gang leader."

"Oh, that'll be great!" exclaimed Spurius Dellius, elevated.

"They say he is Marcus Anicius, though it could be Anicus, or something of the like."

"Yes, I've had four others tell me that name so far. Well," Spurius Dellius slapped his side, "that settles it! I am definitely looking for this man." He added, "What about one other...seems as though he's the ringleader, and with such an unusual name. A...Numerius. Numerius Viccius, or some such thing."

"Numerius! Well, that's the first time I've heard of a living person with that name. And Viccius...what is that, Sabine? Samnite?"

"Campanian...I think," replied Spurius Dellius, set on unraveling the mystery. "Of course, his name might not even be Viccius. Well," he ended loudly, "if there's nothing else for you to add, I should be going. The past nundinum has been very hectic, and there are more to go until my job is done. Next on my list is Marcus Atilius Serranus."

Nepos laughed out loud. "That goose; what's he done? He hid in the Great God's temple when the time for fighting came! No, wait, he was in Jupiter Stator's! Imagine, running from battle and hiding in the temple of the god who heartens and stays fleeing and flagging soldiers!"

Spurius Dellius laughed with him as he walked over the now sunlit terrace to the stairs leading down. "Ah, but one must still ask! I must ask every man in Rome!" And he was gone.

A minute later Ahenobarbus darted up, taking the steps two at a time. "Well, how was it?" he asked with an amused grin.

"The gall of that man, though he looks to have no Gaul in him!" snarled Nepos. "Marrying a Julia, and then talking to me as if he's somebody. Well, I can tell you that some allies of mine have set a great false trail; he's on it now!"

It was the 15th of Sextilis, and Rome was healing. The hot weather struck the elderly down where they stood, and precluded any kind of political activity; well enough for Rome, who would be torn apart by any other kind of turbulent political activity. The most that had happened in the sixteen days between the murder of Gaius Fulcinius and the 15th of Sextilis was the election of Suffect Consul; the Senate, so subdued and quiet, had naturally submitted to Scaurus's wishes and simply allowed him to be the only candidate. A very small and quiet election was held, and the disgraced Lucius Vettius now had a strong colleague in the curule chair with him.

The Tribunes of the Plebs were quiet; no laws were even being promulgated, let alone Vetoed, and it seemed as though Glaucia's sensational Veto would be the last of the year. The Quaestors were doggedly doing their duties and the Treasury, usually in an uproar about the spending of money, were quite satisfied; nothing was being spent. It was like a nice holiday for those in politics, with nothing to be done...except for Spurius Dellius, of course.

And it was to this holiday atmosphere that Marcus Aurelius Cotta had returned on the 14th of Sextilis, to find his wife and children simultaneously delighted and crestfallen. "Whatever's the matter?" he'd asked his nephew-stepson Lucius, who had returned with Longinus Ravilla from Macedonia about a week ago, as they walked to the latter's command tent on the Campus Martius--Triumphing generals were not allowed into Rome's sacred Pomerium boundary until their Triumph--on the night of the 15th.

"Gah, Uncle"--oho, so it was Uncle! This must be something embarrassing! "How do I put this.... After you left Spain, some news was received in your province, and left for Rome...on a faster ship that yours, I supposed. The messenger arrived some ten days ago, and had a message to the effect that the Germans have invaded the Hispaniae."

"What?" Marcus Aurelius Cotta could not credit this news at all.

"I swear to you that it's true! There...there was nothing you could do." Lucius made a wry face and turned away to hide the inevitable tears.

"My son," Marcus Aurelius chuckled, seeming amused. "Lucius, why are you crying? That's not very Roman of you!"

"Gah!" the young man slapped at his own face and wiped the tears away hastily. "Oh, they'll make such fun of you for it! Glaucia--that man's a villain! You won't hear the end of it."

"That's all right," said Marcus Aurelius, putting his arm around his nephew-stepson. Marcus Aurelius Cotta's brother had been more than fifteen years older than him, and so had never suffered the need that second children often needed for dazzling success; his ambition was not too high, and he would certainly never harm or kill a person for his own purposes. No, he was disappointed, but did not hate Fate or the messenger or his own self for this blow to his campaign for the Consulship; it did not matter, so long as it was not disgrace. "Life is life, I hope you're well-adjusted enough to know that. No special dispensations are made for Roman Senators, you know. I might have another chance some years down the road, but the most important thing for me right now is that the futures of you and your brothers are secure--and they are, no doubt about it. My brother"--Lucius's biological father--"was Consul, and I may yet be Consul; your brothers and you have the birth and the brains and the friends to make it all the way. Don't worry any more."

Lucius Aurelius had sobered and taken these words to heart; he appeared sufficiently reassured to crack a smile. "I won't, Dad. Oh, we're almost here."

They were admitted into Lucius Cassius Longinus Ravilla's very nice and spacious tent by the steward, and immediately conducted to the small triclinium. "Aha, the man of the hour!" cried Longinus Ravilla upon seeing Cotta. "And how was Spain, then?" Cotta was seated on the Locus Consularis, the place of honor next to his host, while Lucius Cotta took the couch to the right and Lucius Longinus Junior the couch to the left; since Cotta's women were not present and they would discuss only men's business, no chairs were drawn up for female diners.

When a pause in the conversation allowed for Longinus Junior to butt in, he said, "Why didn't Aurelia come as well? And Rutilia; we could have made it a family dinner," he added brightly--or so he thought--to disguise his true intentions.

Marcus Cotta looked sternly first at Longinus Ravilla, who was giving Longinus Junior a withering look, and then at the young man himself. "This is a conference of men, Lucius Cassius; women should not be present." Marcus Cotta then glanced at his own son, and saw a curiously wry smirk on his face. Lucius Cotta had told his uncle-stepfather of Longinus Ravilla's interest in Aurelia's hand in marriage for Longinus Junior, and it seemed as if contemplation of Aurelia's life with such a dull and unremarkable fiend had drawn Lucius Cotta away from him. No kid himself, Lucius Cotta was ten years older than his sister; he was 28 and not far from the Quaestorship. He would need political allies soon, and Aurelia's hand in marriage was the best way to gain them; since Lucius Longinus would not be a good ally, the Cottae had to look elsewhere.

"Anyway," Lucius Cassius Longinus Ravilla continued uncomfortably. "As I was saying, it will be hard for anybody to beat Gaius Servilius Glaucia. I know that the electors usually like to see two men running for Consul as a team, but they won't be able to resist the...heroics of the man. Truly, you have to admire that about him."

Marcus Aurelius was nodding slowly. "I see that. How can I hope to even try, then? He's a hero of the Forum and of the recent violence, whereas you're Triumphing tomorrow; you're a war hero."

"I can only think of one thing," said Longinus Ravilla, and got a crafty gleam in his eye. "We must show the electors that we are absolutely in concord, and that we will do everything together. I know that they are quite anti-Populist right now, but we will promise them stability; we'll argue that an radically conservative backlash is no way to go. That it is, in fact, just as bad as Populist sentiment; where did thoughtless backlash get them, when Catulus Caesar lost his army, if not into the hands of Gaius Fulcinius?"

"Very sensible," said Marcus Cotta, letting Longinus Ravilla do the talking. He thought he knew where the man was headed.

Lucius Cassius confirmed Cotta's suspicions. "So we'll promise them stability, and must show absolute unity." Slowly and somewhat regretfully he said, "I think, Marcus Aurelius, that a marriage is in order."

Cotta did not ape surprise or ignorance; Longinus Ravilla had no children besides the one son. "I see what you mean, friend. I'll have to think on it."

"What's more is our children will be great allies. Intelligent, noble, knowledgeable...and more. As will we be much greater friends after the union is joined. Don't you agree?" Coming from Longinus Ravilla in the present situation, this question sounded menacing.

"I do quite agree!" said Marcus Cotta, betraying no nervousness, and none of the slow, low anger that he felt. Peddle his daughter off like a whore just to gain the Consulship! Pah! That was for lesser men, who valued political office over their own flesh and blood. "As I said, I shall think on it; it is a generous offer, but remember that my list of suitors for Aurelia's hand is, once unraveled, the length of the Forum!"

On their way home later that night, and in company of two burly and tight-lipped Gallic slaves who loved their kind master and would never give his secrets away, they stopped at a latrine to relieve themselves. "Father," began Lucius when they emerged. "You're not really going to think on giving Aurelia away to Lucius Cassius, right? That's no alliance to speak of, one idiot like him with me and my three brilliant brothers! We'll spend much more effort helping him out than he can helping us."

"Oh," Cotta nodded. "I quite agree, my son."

"Then why didn't you just tell him straight out?"

"I must talk to Rutilia; she'll find me a way to break the news to him after the Triumph. You know she's better at emotional...stuff."

"Mother is great at that," admitted Lucius Cotta, who loved the stepmother he'd had since the age of nine more than he had ever loved his dead biological mother. He frowned, "I don't know how you'll avoid offending Lucius Cassius, though; he really wants Aurelia for Junior."

"Simple enough," said Cotta amicably as they neared home. "He knows me, and he knows what I value. I'll just say that Glaucia and he deserve the Consulship more than me this year, and that I'll wait for a year with better prospects. He'll believe me, you know."

"He'll still be offended," said Lucius dubiously, "that you won't accept his son. He really thinks the boy has brains in him."

"I'll say that Rutilia wants grandchildren that will smite with their beauty," said Cotta, thinking on his feet. "Since she and Claudia"--who was Longinus Ravilla's wife and Junior's mother--"aren't on the best terms anyway, it should be no loss for their relations to deteriorate further. As for you, my son," said a grinning Cotta, "they need never know that you oppose the marriage! Just say that I wasn't willing to listen to you."

"Father, you're a genius!"

"What can I say?" shrugged Cotta as they reached the door. He knocked for the steward and said, before they were admitted, "It's in the lap of the gods."

tuareg109

Banned

FOR WANT OF THE HAMMER

HOMECOMINGS, 647 AVC

HOMECOMINGS, 647 AVC

Lucius Cornelius Sulla pushed past the stunned doorboy and shouted, "What does a man have to do to get some wine around here?" He stomped loudly into the Atrium and it only took a moment for a smooth, oily Greek--Sulla presumed it was the new steward, Trophimus, bought after his dear old steward's death a month ago--to skitter into the room.

Both men stopped, staring at each other. Sulla stood relaxed, stunning eyes half-lidded and arms akimbo, in impressive military trappings; Trophimus's arms were tense at his sides, and he stood on the balls of his feet, eyes wide. Who was this stunning, fair, godlike man? Oh, so beautiful! Trophimus had his answer when the mistress brushed past him and launched herself at the man.

"Lucius Cornelius, you're home!" Caecilia Metella Sullana squealed, and lifted her feet clear off the ground. His athletic frame clearly belied his strength, as her weight didn't even cause his neck to bend.

"It's great to be home, wife!" he growled lustily, and grabbed her waist, kneading her soft, healthy body. "My, aren't you positively glowing!"

"Because you're home, Lucius Cornelius!" she piped in a very high voice. Oh, so cute! What would he do? Her feet met the floor again and she jumped up and down, up and down, and the effect of her body on his, even through her thick, modest stola and his leather pteryges [military skirt] and cuirass, soon became apparent. She stopped jumping and her eyes went wide; not surprising, as she hadn't seen anything of an erection for some ten months.

"You're so energetic! Well, I'll soon fix that," he snarled. He picked her, shrieking with laughter, up and, with a wink and grin for Trophimus, ran to the bedroom. For some hours they laughed and moaned and banged on the walls of the regal bedroom that Sulla, Clitumna, and Nicopolis had once shared; they took breaks, calling for wine and honey cakes; and they muttered intimately of the past few months and events in Rome in between bouts.

After that stunning and long-awaited sex marathon--for Sulla had been traveling for some fifteen days with his peers and thus without any relief--Caecilia Sullana promptly fell asleep, loving dark eyes closing inevitably with tiredness until she began to breath lightly with the vision of her beloved in her head. Sulla watched her for a few minutes before uncoiling lithely and striding naked out of the bedroom. "Trophimus!" he called.

The steward entered, eyes boggling at the snow-white skin of this man, and the twin golden halos surrounding head and groin. How handsome, how well-built. Sulla, typical of him, fancied making the Greek flustered; he put on his most winning smile and used his eyes to great effect. "Come here."

"Yes D-dominus," Trophimus stuttered, and shuffled over to where Sulla stood. Sulla took his shoulder and pulled him close, stroking his arms and then his sides.

"Fine muscles you have, Trophimus. You'll be an excellent steward if you have such a mind; how old are you?"

"T-twenty-six, Lucius C-cornelius."

"Tsk," said Sulla, stroking the back of his neck. "We can't have you butchering my name." He turned abruptly to walk back into the bedroom. At the door he turned his upper body and head back, leaving pure white buttocks exposed to Trophimus's hungry gaze. "Have water for my bath heated, will you?" He entered the room and shut the door, then shook with silent laughter. Ah, he'd been doing it since his youth, and he would never tire of doing it; confounding men and women with his beauty never stopped amusing him.

He sat next to Caecilia Sullana on the bed and thought. His servants were sufficiently afraid of him to not gossip about anything very serious; could he possibly have Metrobius hired as his steward? How old would the boy be now? No, he would be a man; fully nineteen years old, grown into his full beauty, and Sulla hadn't seen him in all those years! No...sadly, it was impossible. The young man's life was the theater, and the role of steward didn't suit him; unfortunately, respectable Senators typically had no need for actors. Sulla, to attain the Consulship which was his birthright, definitely needed to remain respectable.

"Fate does play tricks on me," he muttered to himself. Then the soft knock came at the door and he exited to lead Trophimus into the bathing room. Sulla enjoyed the feeling of the hot, hot water against his skin, and spent some minutes sitting under water, holding his breath. It was an hour before he tired of that old bronze tub in which he had had much fun with Clitumna and Nicopolis, and their slaves; he called the body servant, ready with a towel, perfumed oil, strigilis, and robe, to him.

"Fetch me Trophimus," he said. When the boy couldn't help himself from smirking as he turned, Sulla called him back and, with a vise-like hold on the boy's wrist, dealt a cracking backhand slap to the face. "I've been gone for months, and must see to my accounts you ingrate. Display such a dirty mind before myself or the mistress again and I'll have you crucified."

Eyes watering and lip bleeding, the boy nodded and apologized many times before Sulla let his wrist go; the boy stumbled for the room and Trophimus appeared a minute later. Sulla pointed to the cleaning implements the boy had left and said, "You should know how to use those, Greek."

"Yes Dominus, I do."

Sulla stood and stepped out of the tub. He walked over to the comfortable massage table and laid down. "Massage me first, then oil and scrape me. Tell me of my accounts, my lands, and any believable rumors you've heard."

Trophimus began to rub; as Sulla listened, he couldn't help but notice how soft and graceful Trophimus's hands were. Sulla had spent months at war, with only the hard and callused handshakes of military men to experience; he couldn't help but get hard again, despite the morning with his wife. When Trophimus was done massaging him, he turned over and propped himself up on his elbows, displaying fully the proud member.

Trophimus gasped slightly and his eyes widened; he was transfixed by Sulla's beauty. Sulla's steady gaze drew Trophimus's eyes. "I trust you can be discreet? You're my creature now, you know."

"Y-yes Dominus," said Trophimus. Sulla drew Trophimus to him.

Marcus Livius Drusus Junior's homecoming was somewhat different; in fact, it was very different. For one, he was greeted by his father, not his wife--well, he had no wife. Also, he was allowed no relaxation or leisure; he was pushed straight into politics. Not that he didn't enjoy it! Oh no, Marcus Livius Drusus Junior was nothing if not a born politician. Many of his friends came to visit their new war hero, and his father crowed far and wide of his son's achievements; three sets of three golden phalerae [disks hanging from a cuirass during parade], and three golden armbands! Though Publius Rutilius Rufus was Drusus Junior's commanding officer and uncle, he was also known as being a fair man who tolerated no nepotism; no, Drusus Junior's decorations had merit, and all who knew him believed it instantly.

"It looks like Aurelia's taken, son," said his father after some hours of more important talk. "I know how much you wanted her but...so did half of noble Rome, so you're not the only one."

"Wow, what a comfort that is," said Junior to his father. The father just grinned. "By whom? Who has Marcus Aurelius chosen?"

Marcus Livius Drusus's face twisted. "Ugh, that insufferable mite named Lucius Cassius Longinus Junior."

"What! That piddling fart Longinus over a war hero like me?" Drusus was dumbfounded, and his large dark eyes appeared even larger. "Is this true for certain, or just a rumor?"

Drusus, somewhat less intelligent than his son, looked uncomfortable. "Well, it is technically a rumor, but I don't see how Cotta can hope to run for Consul with Lucius Cassius and win if they don't present the most unified front since Metellus Diadematus and Scaevola Augur!"

"Maybe Marcus Aurelius knows he doesn't stand a chance. Maybe he's running for the hell of it," said stubborn Drusus Junior; his father, exasperated and out of his depth, threw his arms up in the air and conceded the point with alacrity.

Soon they departed for the home of Quintus Servilius Caepio, who was holding a banquet in honor of Marcus Livius Drusus Junior, who was his dead wife's brother's wife's nephew; Caepio had been married to a Rutilia Rufa, who had died before bearing him any children. She was the sister of Publius Rutilius Rufus, of course, who was married to a Livia Drusa, the sister of Marcus Livius Drusus Senior. Caepio's current wife was a Domitia Ahenobarba, and mother of young Caepio, who was currently in command at Bylazora in Longinus Ravilla's stead.

Also invited were Drusus's wife Cornelia Scipionis and daughter Livia Drusa; Gaius Julius Caesar Strabo Vopiscus, who had served with Drusus in Gallia Narbonensis, albeit with less decorations; his brothers Lucius Julius Caesar and Quintus Lutatius Catulus Caesar; Quintus Lutatius's son by the dead Domitia Ahenobarba; and Quintus Lutatius's wife Servilia Caepionis, who was Caepio's sister. The family connections made foreigners' heads spin, and gave many a New Man grief; to noble Romans, however, it was mother's milk.

"A shame Publius Cornelius couldn't be here," said Caepio. Publius Cornelius Scipio Nasica, hero of justice that he claimed to be, was busy actually collaborating with Spurius Dellius to find the murderers of Gaius Fulcinius and his merry men; the only difference was that Scipio Nasica, when he found the murderers, planned to thank them heartily and hide them from the Urban Praetor's court until the whole thing blew over. If the conservatives had their way in the elections and a Boni man was elected Urban Praetor next year, which looked very likely, then the whole thing would indeed blow over and be forgotten. Traitors had gotten their just desserts, and the whole matter wouldn't be pursued for long.

Besides, Scipio Nasica was married to a Caecilia Metella; since her whole family had gone over to supporting conviction against Catulus Caesar in the big trial now five months past, inviting them would have been awkward, even though Scipio Nasica had wholeheartedly supported Catulus Caesar during the entire trial.

Drusus Junior had been thinking about this, and so his mind was on the elections, which would be held in eleven days; today was the 3rd of September. "I'm sure he's too busy fuming that Glaucia will manage to beat Marcus Aurelius." Since none of them liked an opportunistic man with no concrete morals like Glaucia, and all knew Scipio Nasica's upright and aristocratic nature, this comment was not at all deemed to be in poor taste.

"The poor boy takes things too seriously," said Catulus Caesar. "He should be calm and collected...cool," he drawled.

"Scipio Aemilianus," said Caepio with a nod to Drusus's wife Cornelia Scipionis, who was the man's daughter, "was cool. But not a Cornelius Scipio by blood, of course."

"If being cool entails being like Quintus Caecilius Metellus Nepos, then I want no part of it!" said Marcus Livius Drusus Senior. Given that one woman present was a Domitia and Quintus Lutatius's dear dead wife was a Domitia, he couldn't well have included Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus in his diatribe.

"Where did that come from, I wonder! Stay cool, Marcus Livius," said Caepio, and the party laughed. "Truly though, I for one am finding it very hard to stay cool. All and well," he said to Drusus Junior, "that your uncle Publius Rutilius is Cotta's friend, but I for one am no friend of his friend Lucius Cassius! Gaius Servilius Glaucia is at least an intelligent man; I think I'll vote for him!"

"What's this," asked Drusus Junior, eyes wide. "Something about Macedonia?" Oh, he was shrewd!

"Yes, absolutely! My son writes me that those wretched peasants that make up the legions there refuse to listen to him! A force of Dardani ride by, positively begging to be followed and annihilated--wearing so much gold, young Quintus writes me--and the legions just refuse to follow him."

"Astonishing," said Drusus Senior, eyes rolling in his head at this injustice.

"Go on," said Drusus Junior, who disliked Caepio's tone. Fully indoctrinated before serving in Uncle Publius's legions, experiences there had opened his eyes to the life of a ranker soldier. If they refused to do a job, they had a very good reason. And that aside about gold--well, all knew that a Quintus Servilius Caepio could never resist gold. It honestly sounded like an ambush waiting to happen.