You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

FOR WANT OF THE HAMMER

- Thread starter tuareg109

- Start date

tuareg109

Banned

FOR WANT OF THE HAMMER

A NEW YEAR'S TRAGEDY, 645-646 AVC

A NEW YEAR'S TRAGEDY, 645-646 AVC

Publius Rutilius Rufus was woken on the 29th of December by the gentle shaking of his shoulder. Like most active men living on a proper diet, no matter what age, Publius Rutilius, once over the walls of sleep, opened his eyes and sat up immediately, not tired at all and able to think clearly. He saw that it was his attentive steward, an educated Greek with the very regal name of Eudamidas, who had woken him up.

He frowned at the torch Eudamidas was carrying; no light filtered through the door behind him, for it was completely dark outside, a moonless night. "What is it, Eudamidas?" he asked curiously.

"Dominus," said Eudamidas, holding out a sealed letter. "A most urgent letter from the Pontifex Maximus; his messenger was distraught." Publius Rutilius's eyebrows went up and he took the letter, standing, pulling on his slippers, and following Eudamidas to his study. Publius Rutilius saw his own breath, ghost-like in front of him, as Eudamidas lit two of the lamps; Publius Rutilius was no wastrel, and in any case more lamps would not aid his sight or the cold of the night.

Publius Rutilius shivered as he sat in the cold high-backed wooden chair with only his wool tunic separating it from his skin, and bent his head to the desk to read the letter. It was simply a folded sheet of paper, sealed with the ring of the Pontifex Maximus hastily blotted on wax, and with the writing: Lucius Caecilius Metellus L. f. Q. n. Dalmaticus Pontifex Maximus to Consul-Designate Publius Rutilius Rufus scrawled under the seal in Greek.

Frowning again at such formality, Publius Rutilius picked up his letter-opener. Something terrible has happened, I know it. The apprehension made him arrest his hand's movement through the air; it was Pandora's Box all over again, and he would release the evils of the world into his household. He chuckled at such dramatics and slit the seal, though still with his heart beating hard and slow.

Consul-Designate Publius Rutilius Rufus, a matter of great urgency concerning the Consuls' inauguration on the 1st of January in three day's time requires our immediate attention. Please assemble at my house, the Domus Publica, as soon as possible. Be it day or night, sunshine or rain or snow or thunder, convey yourself to the Domus Publica immediately.

Lucius Caecilius Metellus L. f. Q. n. Dalmaticus Pontifex Maximus

Publius Rutilius set the letter down gravely. An electoral irregularity was indeed a grave matter; he would hurry to the Forum Romanum with all haste. "Eudamidas," Publius Rutilius commanded, "get your thickest tunic and cloak on, and then ready my own toga and cloak. We're going to the Domus Publica."

Half an hour later they stood in front of the Domus Publica just a bit out of breath, thanking the gods for warm thick felt boots. Eudamidas banged urgently on the door and they were immediately let in by a tired- and harassed-looking doorman. The Pontifex Maximus's steward, not so harassed, waved for Publius Rutilius to follow him, which he did; Eudamidas was left waiting in the reception room.

Publius Rutilius was led to the left, through an open arch to the Regia part of the Domus Publica; the Vestal Virgins too lived in the Domus Publica, separated completely from the Pontifex Maximus except through their own door into the reception room. Through the walls he heard their own shuffling, and some muted whispers.

They quickly came to the atrium, where a large stone brazier had been set up. Around it, all wrapped up in wool cloaks and wraps as if in cocoons, were the Pontiffs Lucius Caecilius Metellus Dalmaticus Pontifex Maximus, Marcus Livius Drusus, Marcus Aemilius Scaurus, Publius Cornelius Scipio Nasica, and Quintus Mucius Scaevola--only Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus Senior was missing. Then there were this year's Consuls Servius Sulpicius Galba--looking dour and with dark circles under his eyes--and Quintus Hortensius--looking very tired and flabby. Last of all were the Consuls-Designate Quintus Lutatius Catulus Caesar and Publius Rutilius Rufus himself.

[Yay name dump!]

"Come join us, Publius Rutilius," said Lucius Pontifex Maximus, wearing the voluminous crimson cloak of his station well upon his frame. "Tonight's one bastard of a cold night."

Not astounded by this familiarity--for in the Roman culture formality often only extended to official missives--Publius Rutilius did as he was asked. When he had vigorously rubbed his hands together and had the warmth flowing through him, Lucius Caecilius began to speak.

"One of our number, integral to the inauguration of the Consuls, is missing today; nor shall we see him alive again."

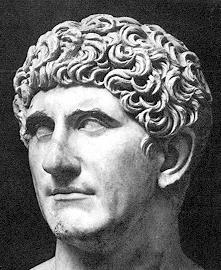

Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus Senior (589-645) at the age of 56, the day before his death

They immediately began to speak all at once; some in genuine grief, others politely expressing sorrow. Lucius Caecilius, Publius Rutilius noted, had a mischievous glint in his eye to go along with a dutifully sorrowful expression; few people had liked the abrasive, venal, temperamental, and somewhat lazy Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus. Even fewer liked his son, who was likely to take his place. Though it was a tradition not backed up by law, it was still common practice that when a Pontiff died, his eldest son--if suitable and of age--took his place. This kept pontifical power in the same few families, and ensured that the ancient ratio of three Patricians to three Plebeians--set during the Conflict of the Orders over three hundred years ago--remained in balance.

However, there had been slight deviations. Only Publius Rutilius couldn't see why Lucius Caecilius's eye was glinting so. "How did he die?" Publius Rutilius broke the expected chatter.

"In his sleep," said Lucius Caecilius simply. "Coronary failure, stroke, who knows? The God Somnus of sleep delivered him to his brother Mors of Death, and we know no more."

There followed a short silence that was broken by Marcus Aemilius Scaurus, who burst out into laughter. Scipio Nasica and Marcus Livius Drusus, the dead man's best friends, stared at him resentfully until he raised his arms and said, "Okay, okay, don't kill me; but, I do believe I've seen what our Pontifex Maximus is getting at."

Catulus Caesar's lips held a small smile too. "How exquisite," he drawled, "to be rid of that vile temper." He stood taller and shouted, when Scipio Nasica and Drusus began to move, "I do not mean the dead man! Think! What is three days from now?"

"The inauguration," said Consul Servius Sulpicius said quickly, eager to be deemed intelligent, but not having understood.

"What does that have to do with anything?" snapped Quintus Hortensius, whose mind served well in the law courts but not in the political arena. "Who cares?"

Publius Rutilius, who had been in Africa for the past two years, understood as soon as Catulus Caesar said "vile temper". "Oh, it's wonderful!" he said, and spoiled the fun of the four--for tight-lipped Quintus Mucius Scaevola, while contributing nothing to the conversation, shook in silent mirth--revelers. "An inauguration of any elected magistrates requires the full College of Pontiffs to preside. Since Gnaeus Domitius is dead, you Pontiffs must select a new one within the next two days, instead of being allowed the usual two or three weeks to decide. This means that poor dead Gnaeus Domitius's poor elder son Gnaeus isn't going to be in Rome on time."

Drusus and Scipio Nasica, very loyal to their friend, didn't like it, but the logic could not be fought. There was simply no way for word to be sent to Africa, and then for a man to journey from Africa to Rome, in time for the inauguration. Still, the haughty Scipio Nasica made an abortive attempt all the same: "We could postpone the inauguration and have interreges appointed by the Senate," he suggested. Drusus immediately latched onto this, but the two were shouted down by the other seven men present, who held no love for Ahenobarbus Junior.

Marcus Aemilius Scaurus hooted, "Try to postpone the inauguration and I'll have my Tribune of the Plebs veto it so fast that your heads will spin!"

"Thank you," said Scipio Nasica icily, "for admitting to being partner to bribery."

That made Scaurus hoot all the harder, and it was this amusement that won Drusus over; for though Drusus had loved Ahenobarbus Senior as a friend, the situation was truly too impossible to go through all the trouble, and have to deal with an unruly young man besides. After this defection, Scipio Nasica too gave in.

Now all--except for Drusus and Scipio Nasica--in a healthy degree of camaraderie after this comedy, they listened to Lucius Pontifex Maximus. "And so, who will replace our late colleague?"

"Well, let's keep it in the family," said Publius Rutilius craftily. "Why not give the job to Lucius Domitius?" Scaurus burst into peals of laughter again, and even Scipio Nasica had to give an ironic smile.

The five Pontiffs, being Romans all and lovers of the bizarre besides, decided to make Gnaeus Domitius's younger brother Lucius, currently in Rome and all of twenty-eight years old, Pontiff in his father's stead.

Gauda was busy playing the fascinating game of chess, imported from the Seleucid Empire, when he heard the vicious screech from across the Governor's House in Utica. His opponent spun around and Gauda, already desperately looking for a way out of his predicament, found it; he screeched and stood, leaning forward, and thus sent the board flying. His Numidian companion, Nabdalsa, looking dejected, hurried to pick up the pieces of his victory while Gauda hurried to the screech with a smile on his face. Beat the King of Numidia, would he? Well, that showed him!

The other side of the house being only a few dozen paces away, Gauda reached the doorway to the Governor's Study, which was blocked by several soldiers. "Out, all of you! Idiots, leave, I'm fine!" The men hurried away, well aware of Gnaeus Domitius Junior's temper, and had no qualms about letting him spend his fury on Gauda.

"Why, Governor Gnaeus Domitius, whatever is the matter?" asked Gauda, leaning against the door frame.

Gnaeus Domitius stared with hatred and red-rimmed eyes up at that idiot grinning face of Gauda's. Completely useless, never doing anything productive, and always being taken care of by others--which ironically also described Gnaeus Domitius quite aptly--was Gnaeus Domitius's opinion of Gauda, and it all came to a head today, for two days ago had been New Year's Day.

Gnaeus Domitius had started drinking on the morning of the Eve, and had not stopped until nightfall on January 1st, when he passed out after 36 hours of nonstop drinking. 36 hours after that, on the morning of January 3rd, he had woken up puking again, and still a little drunk; in addition, there was blood in his vomit and in his stool. Little hammers banged mercilessly in his head and thousands of suns appeared in his eyes at the slightest instigation. Gauda's idiot grin was the icing on the cake.

He rose to his feet and raced to Gauda's side, mindlessly pummeling him with fists and elbows, and then anything within reach. A dozen old missives and letters from Rome were torn up and rubbed into Gauda's wet--from tears and snot--and bloody--from cuts, of course--face. The guards, having let this go on for about a minute, decided to intervene before King Gauda became seriously injured; their real commander, after all, was Quintus Caecilius. What would he think if they let Gauda come to real harm?

They pulled Gnaeus Domitius off of Gauda with difficulty; all the while he screeched, "You're Romans, you're all Romans! Don't stand for this barbarian filth, let me kill him! I'm only here because of him, I could have been a Pontiff!" All his life Gnaeus Junior had lived in the shadow of his father's disappointment; instead of enduring it quietly like Marcus Aemilius Scaurus Junior, he had sought escape through wine and whores, which just added to his father's contempt.

Now, being eclipsed by the younger and more inexperienced Sulla and his own goody-two-shoes brother Lucius--darling of their father--had driven him over the edge. He struggled and struggled, until the twenty guards that changed shifts of holding him back succeeded in tiring him out, and he dissolved into a wretched pile of tears. Warily and wearily, they backed away and left him alone, closing the door behind them. Gauda was by now locked away in his rooms, shakily taking a nice hot bath with two young women.

The Pontiff Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus upon being selected in 645 AVC, at the age of 28; he was bald his entire life

After many minutes Gnaeus Domitius recollected himself and rose to his full height, which was not so great. "I will destroy them."

Is it too over the top? What do you guys think?

Last edited:

tuareg109

Banned

This TL is great.

Grouchio said:It's perfect. If gnaeus starts a civil war, Roman support/supplies are fucked along with Sulla's army!

Actually, this is just a minor diversion, an event of drama and family strife. The legions are propertied men, and wouldn't blindly follow a Proquaestor.

Man, I'm just bursting your bubbles left and right, aren't I?

tuareg109

Banned

FOR WANT OF THE HAMMER

ROMA ET ITALIA PART 1, 646 AVC

ROMA ET ITALIA PART 1, 646 AVC

For a man of action, Sulla was having a great time at his villa in Circei. With no important news from Gnaeus Domitius in Africa, Quintus Caecilius and the rest of his staff stayed in Rome or elsewhere pleasant in Italy until the weather in Africa and Numidia improved--or worsened, depending on who was being asked. Winters in Africa and Numidia were wetter than the summers--which wasn't saying much; Rome's yearly precipitation was about three times Africa's or Numidia's--and this extra water, along with the extra snowmelt from the Atlas Mountains, meant that every dry stream bed and little trickle in Africa and Numidia turned into a torrent in the winter. This climatic phenomenon precluded large army movements, and so Roman Africa was safe until April.

And Sulla would indeed enjoy being in Rome and Circei with his wife and friends until April. The temperature in Italy had dramatically improved in mid-February so that now, in early March, a man could walk outside clad only in tunic and toga and yet begin to sweat a bit. It was the perfect time to furlough to Circei; far removed from the political and gossip machines of Rome, and with only each other and a few cheerful slaves for company, it was just what Sulla and Caecilia Metella needed.

The beautiful Mount Circei, which provides a great view for hikers and a pretty sight for tourists and vacationers; it is a steep 1,700 foot mount surrounded by the sea and very low marshes

Indeed, Sulla had softened a bit after marriage. Caecilia Metella had endeared herself to him by being a good, dutiful, unassuming, and efficient wife. From his talks with Publius Rutilius--less likely by far to lie than the girl's father and brother, the two Quintuses--he knew that she had the intelligence and the know-how to manage her slaves properly, and choose out the best ones with no regard for looks or charm. She had a very good head about her, and Sulla knew from his own walks with her that no trader could ever fleece her. In addition to all that, she wasn't even boring. She knew the Comedies as well as the old, boring, expected Classics; she knew how to discretely poke fun of this person or the other; she was politically witty and savvy. After overcoming the initial shock--for she had been a complete virgin on their marriage night--she had also taken to her marital duties and the learning of them with gusto, for she truly loved Sulla, and both of them fell asleep quite satisfied almost every night at Circei.

It was indeed a proper honeymoon, but it was broken by the father-in-law, perhaps jealous for his daughter. Or so it would have been had Sulla's life been a comedy, but Sulla's life was--alas--mostly bizarre tragedy mixed with dabs of myth and sacrifice. Quintus Caecilius Metellus Senior wrote for a more important reason:

Greeting dear Lucius, good son-in-law. How are you? How is my dear daughter doing? No doubt your vacation at Circei is excellent for the general health and well-being; however, if you wish to be my Legate this year you must cut this honeymoon short.

As temperatures in Italy rose, so did temperature in Africa Province. The campaigning season began earlier than usual, and I must be there as soon as possible. Enclosed is a copy of Gnaeus Domitius's letter to me; I dare say that its contents won't please you.

Take care and send a response immediately.

Regards, Quintus Caecilius Metellus

Sulla frowned over across the desk, where Caecilia Metella sat in the client's chair quite indecently dressed in his own tunic and with her legs folded under her; she was reading a letter from her infamous aunt Metella Calva, brows creased. Well, Quintus Caecilius was no Publius Rutilius Rufus; Sulla knew if a letter was by that old dog when he had to lift its weight with both hands.

Sulla bent to his desk once again and removed the second letter from the packet. This was simply a Greek scribe's copy of Gnaeus Domitius's letter, folded in half, and didn't bear a seal or distinction of any kind. Sulla unfolded it and read:

Proconsul Quintus Caecilius, I'm writing to you because the warm weather I've heard of in Italy has extended down to Africa Province. The rivers have for the most part dried up, and--thinking half a year ahead--I invaded coastal Numidia with four of the six legions left to garrison the Province. They had much grain stockpiled, Sir, and I took it upon myself to transport this to Africa, where it will serve us well this year and next, for the early summer means less grain production.

I have also come into battle with a Numidian army of about 10,000 men, which we ambushed in the treacherous twists and turns of the Tell Atlas foothills; I myself commanded a little over 19,000, which is a fair advantage. I doubt that King Jugurtha was the commander, given his legendary military prowess, for we chased almost every single Numidian down, and lost only 3,000 of our own men. Having collected sufficient grain to feed the City of Rome for three years, I retreated to Africa Province, and now await your command.

All other things in Africa remain the same. Prince Gauda is the same as ever.

Your loyal servant, Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus

Sulla's pale, pale, snow white face--so quick to return to its original state after the adventures under the sun in Africa--began to mottle with red as he read; by the time he finished, the deep angry flush of his face complemented his fiery gold hair quite handsomely. Caecilia Metella, sensing something amiss, looked up at that moment and audibly caught her breath; he was the most beautiful creature she had ever seen. Given the color of any Roman he would have been simply handsome, as Gaius Memmius was and all of the Julius Caesar clan were. However, the absence of any color from most of him made him different; where Gaius Memmius or Sextus Julius Caesar had the beauty of a model, Sulla had the alien beauty of a snake or a scorpion.

The anger in that stern face, and in those hard lips, and in those icy eyes, only served to enhance that beauty; it looked august and dignified now, instead of prancing and artificial. Caecilia Metella shuddered as Sulla continued digesting the contents of the letter. Great Numina! Sulla's mind raged. Dereliction of duty, usurpation of the Proconsular prerogative, illegal warfare...there wasn't anything that Gnaeus Domitius hadn't done wrong, in military terms.

He had even fought an army before ascertaining its allegiance; Sulla knew very well, for example, of the revolt against Jugurtha and for Gauda in coastal Numidia. Given the "enemy's" obvious inferiority when considering that it lost a battle against an idiot dullard such as Gnaeus Domitius, it was quite likely that this was some of the peasant and city rabble that supported Gauda. Now, Rome would have less allies in coastal Numidia, and perhaps the rebellion would end; better King Jugurtha that you knew, than crazed Romans who attacked allied armies, right?

It was also clear that, instead of just conducting a military campaign, he had gone raiding and marauding with the legions; how else could one stockpile so much grain? Gnaeus Domitius's actions were not tantamount to an act of war against the Republic, but they weren't too far either.

And yet...to avoid Jugurtha's pincer movement, and to get a head start on him, invasion had been a clever idea. Sulla would be lying--unashamedly, he admitted, but still lying--if he said that he too would not have gone to war with six legions at his command...in different circumstances. Ahenobarbus knew, since Quintus Caecilius and Publius Rutilius had briefed all the staff on the revolt in coastal Numidia and the possibility of seduction or infiltration. With the northern theater secure, any knowledgeable general would have moved south and tried to stifle the power of the desert tribes. However, there were little riches to be taken out of the hills and deserts. It was all about the grain...was Ahenobarbus aiming to manipulate the price? In any case, Sulla could not condone Ahenobarbus's actions--he would give him a stern talking-to, indeed--but he could still understand them. When the vote comes up for whether or not to convict him, I will write ABSOLVO.

Sulla drew out of his musings to find his wife still staring at him in adoring awe. Unable to find the heart to snap at her, his scowl became a twitch that tugged the corners of his mouth up, and he asked, "What news do you have, dear?"

She coughed and blushed, for Sulla could make even the most intimate women blush, and blurted out, "Oh Lucius Cornelius, isn't it wonderful! Lucius Licinius's cousin Licinia Crassa and Quintus Mucius Scaevola have had a little girl!"

Marcus Antonius and Gaius Memmius were lounging in the former's large, lavish dining room, in his large, lavish house in the Carinae, an exclusive neighborhood of large mansions, the most modern baths, and several open parks that sprawled over the Velia, the Fagutal, and the western end of the Oppian Mount--all part of the Esquiline. It afforded a beautiful view over the Forum; the Palatine; the Subura; and the area between the Palatine, the Carinae, and the Caelian Mount, which mostly housed craftsmen wealthy enough to avoid the stews of the Subura.

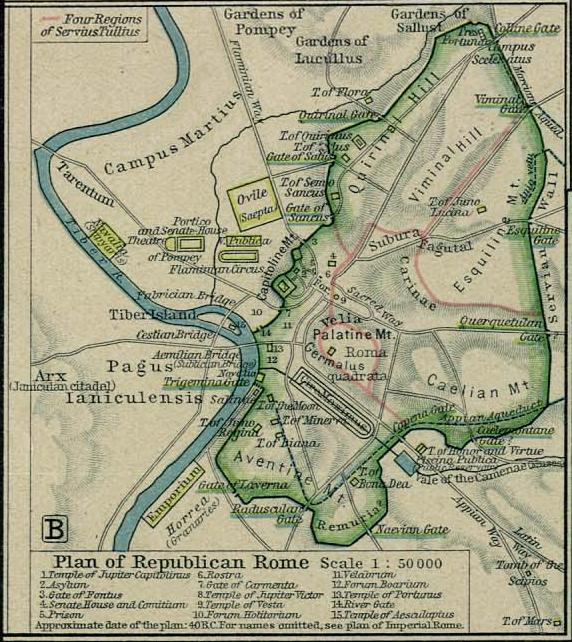

Map of Roma Urbs in OTL's 702 AVC. Ignore Pompey's Theater and Curia

Marcus Antonius's family had been noble for three generations, and he was considered quite safe--if a bit remote and unorthodox--by his senatorial peers; what was more, though, was that he was utterly dependable, as his father had been. "Give Marcus Antonius a job," they said, "and it is sure to be done right." So they had said of his father and grandfather both. His great-grandfather they had probably cursed as a New Man parasite, but that was so far in the past that he didn't give it any mind; who could know for sure?

Gaius Memmius was unorthodox in the extreme; it had been he who, as Tribune of the Plebs in 643, one-upped Gaius Mamilius in his accusations and indictments of men suspected of supporting Jugurtha. Where Gaius Mamilius was now commonly known to have acted in self-interest, for the silver of Spurius Postumius, Gaius Memmius had done it solely because it was the right thing to do; in the political arena of Rome, that made him a dangerous and unstable creature. Then, as top-polling Quaestor and thus Curator of the Grain Supply in the previous year (645 AVC), he had cleverly eluded all of the attempts of Marcus Aemilius Scaurus Princeps Senatus, that bastion of Republican virtue and conservatism, to uncover evidence of wrongdoing.

Lucky for the hounded Gaius Memmius that he had hid his wrongdoing well, for there was indeed a lot of it. Only he and his good friend Gaius Flavius Fimbria, by a happy stroke of luck elected Praetor in charge of grain and trade disputes that same year, knew of this. With the inside information available in both their posts, and with Fimbria's senatorial boot on many merchants' necks, the two had managed to amass an enormous quantity of grain, now privately and secretly stored, to be sold at high prices when the normal supply ran out--for Memmius and Fimbria together had bought over 10% of the market. It spoke for Memmius's skills as an accountant and webmaster that Scaurus hadn't found anything; it spoke for the integrity of all his other friends that they knew nothing of it, having been deemed much too likely to divulge the secret.

Fimbria wasn't at Marcus Antonius's lunch party because, as Propraetor, he had been assigned the province of Sicily to govern; oh, how much more grain he could wheedle out of them! And Gaius Memmius with barely a cut in the deal!

To the detriment of them both, however, that rebellious ass Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus had shit upon all customs and traditions when his brother was elected Pontiff instead of him, and now there were three year's worth of grain sitting in Utica. If Gaius Memmius would've risked it he could've sent a slave or agent to burn the whole stock to the ground, but he regarded that as too chancy. No, it looked as if Gaius Memmius and Gaius Flavius Fimbria would not be Consuls in a long time--for they had poured all their resources into the grain manipulation venture, in the hopes that it would yield profits enormous enough to comfortably run for high office--unless some miracle occurred.

Not revealing his distress to Marcus Antonius, Gaius Memmius said, "What on Gaia's great Earth do you think that idiot Ahenobarbus is doing in Africa?"

Having been over this topic countless times before with countless other men, Marcus Antonius shrugged, eyes closed. "Trying to show his worth? Trying to lure Quintus Caecilius there so he can kill him? Trying to make the legions mutiny? Anything he could be doing, is stupid," Marcus Antonius concluded.

A bust of Marcus Antonius Orator at the age of 37, in 646 AVC

"What was all that idiocy about the grain? We always have Italian Gaul if all the other provinces fail miserably, which will never happen."

Marcus Antonius, who was not blind--physically or metaphorically--opened one shrewd eye and focused it on Gaius Memmius. "I don't know why that should concern you so much, Gaius."

Gaius Memmius, a career politician, kept his cool. "First off, my position as Grain Curator last year has made me quite anal about such things; and second off, three thousand Roman men of quality died to supply this grain. Not everlasting peace, not an annuity of grain from Jugurtha, but a supply that could rot in Utica the next winter; I've heard that their granaries aren't of any acceptable quality."

"So we ship it to Rome," said Marcus Antonius, who had closed his eye in the middle of this diatribe. "As for the rest, I can see--and do indeed feel--your concern. Oh, Gaius Memmius, where will these aristocrats lead us?"

So I want to make sure of the clarity of my writing. It seemed to me that the whole Memmius/Fimbria partnership and the other persons involved would seem, to an outsider, very complicated. Can anybody confirm or deny this?

Thanks.

Last edited:

tuareg109

Banned

FOR WANT OF THE HAMMER

ROMA ET ITALIA PART 2, 646 AVC

ROMA ET ITALIA PART 2, 646 AVC

Lucius Licinius Lucullus called on his friend Gaius Fulcinius late in April, after the uncharacteristic warmth and dryness of February and March had given way to light afternoon showers that left the streets steaming and humid sicknesses in the air. Though Lucullus was very wary of New Men in general, this Gaius Fulcinius was a good sort. He didn't want to rise far above his station, and he was willing to help senatorial colleagues in certain matters that might benefit him, and all Romans besides.

"Lucius Licinius!" cried Gaius Fulcinius expansively, arms stretched wide. He had moved from his study into the hallway, for one in Gaius Fulcinius's position did not make a Lucullus sit in the client's chair. "Let us take a stroll in my garden!"

Lucullus let himself be led into the peristyle garden, which was thick with heavy, aromatic trees that gave much shade. The garden immediately set him at ease, and he smiled as his pace slowed. Gaius Fulcinius, a native of Arpinum on the Samnite border, had spared no expense in the selection of his home; it was ideally suited to his purposes. It was small and efficient, for he did not intend to entertain many people, and its garden was enormous as peristyle gardens go, with a few interweaving paths and many different types of tree, bush, and flower. Gaius Fulcinius loved nature; and, though his own nature meant that city living was to be his fate, he didn't care about the expense--monetary and in prestige--that it took to have such a large garden.

Portrait of Gaius Fulcinius in the year he entered the Senate as Tribune of the Plebs, 646 AVC

"So," began Gaius Fulcinius, "how is your family?" The socially able Gaius Fulcinius had learned very quickly that any explicit mention of Lucius Licinius's wife other than in the guise of the general "family" resulted in tiny but perceptible changes to Lucius Licinius's dispositions. These changes were important enough that they could change agreement to argument; Gaius Fulcinius, well aware of these little tricks, used them as often and as effectively as he could. And they got him far.

"Oh, doing quite well," Lucullus grinned. "Lucius is really getting the hang of riding horses, and Marcus beats every comer when it comes to wrestling. Soon I'll just have to send them to the Campus Martius with a slave; I can't go every day."

"Oh, congratulations, Lucius Licinius, on such strong boys. Indeed, they must be put in a slave's charge, for you have important work to do."

"Of course," said Lucullus, drawn easily to this conclusion. "In fact, that is why I've come to see you today." They turned a corner and reached the center of the garden where a stone bench, worn by years of enduring Gaius Fulcinius's backside, stood in the sunlight. Not saying anything, the host motioned for Lucullus to sit, and did so as well.

Eventually Lucullus simply continued. "It's somewhat of a difficult matter, this thing that I'm going to propose, and a lot of the Senate will be against it."

There was a pause, which Gaius Fulcinius filled by properly saying, "That is right up my alley, Lucius Licinius, believe me."

Lucullus grinned almost as ferally as Sulla could, and continued quickly, "What I want, essentially--the outcome of the law--will be that no man can misuse the trust of the Republic and the People. I want every man who loses an army, and every man who goes marauding without permission, and every man who rapes provinces of gold and grain to the detriment of society, to be prosecuted to the full extent of the law, and either be sent into distant exile, or thrown off the Tarpeian Rock."

Gaius Fulcinius swallowed after this uncontrolled diatribe; he saw that Lucullus was sweating--whether from passion or nervousness, he did not know. "I know," he said gravely, "exactly what you want, my friend."

"I'm no legal genius," said Lucullus. "Guide me through it."

"It's simple. Both criminal and civil juries now, no matter for what crime, are Senatorial juries. A jury made up of Senators is almost 100% sure to acquit one of their own, of course; and even if a man's crimes outweigh his influence, enough of the selected voters don't care enough to observe the facts of the case. They just vote to acquit no matter what. So it has been since the death of Gaius Gracchus. The Senatorial jury will let Senators off the hook--except those like Marcus Junius Silanus, who have erred greatly and--more importantly!--have very few connections--in almost every case. So we give the courts back to the equestrians."

Lucullus's breath hissed between his teeth. "Are you sure that's possible, Gaius? You'd be viewed as the worst kind of demagogue, trying to divide the classes of quality."

Gaius gave a flashing smile. "Of course it's possible, and they see me as a demagogue no matter what I do, so long as it's what they don't want. With the equestrians in charge, any Senator who commits any one of these offences--each grievously damaging to business and trade--will come under the total ire of the equestrians. There's no question that any guilty man coming under that jury's power will be convicted and shipped off to Massilia or Smyrna or Alexandria or whatever."

"Gaius Fulcinius," said Lucullus smiling, "that's exactly what I want. Do it, and you shall be famous!"

"Not as famous, I should hope," said Gaius Fulcinius, grimacing, "as the Brothers Gracchi!"

Mini-update?

tuareg109

Banned

The Roman Republic confuses me, but the writing is great.

This should help.

Pururauka said:Have to say my friend, your writing is top notch!

Thank you!

Massa Chief said:Good TL- I like the pace of updates!

Yeah, I'm wondering whether I've broken a record or something. 12 pretty substantial updates in 8 days, and I ain't even feeling it.

Thank you.

tuareg109

Banned

The Roman Republic confuses me, but the writing is great.

EDIT: Just read every word of that image, and I must correct/add a few things. The Aediles did not assist tribunes/other magistrates; they were responsible for the holding of public games, and for the upkeep and cleaning of public buildings, monuments, and sanitary structures (aqueducts and sewers), all this often out of their own purse. To be Aedile was an expensive but surefire way to bolster your popularity and notability.

Only Plebeian Citizens could be Plebeian Aedile or Tribune of the Plebs; any citizen fulfilling other requirements could hold all other magistracies.

The Senate debated on issues and gave out its opinion, which was usually listened to; however, in the event that their decision was unpopular or didn't fit with some demagogue's plan, a Tribune of the Plebs could veto it and make his own law about the topic at hand.

2 Censors (having already been Consuls) were elected every five years. They let building and tax-collecting contracts, and sometimes funded and oversaw the building of important new roads. They took the Census, added and removed citizens from the official tablets, raised or lowered a citizen's property class depending on financial changes, and could add or remove Senators from the Senate due to moral or financial laxity. One Censor could veto the other.

2 Consuls (by tradition aged 40+) were elected per year; the Senior trumped the Junior's military command, and held the fasces (convened Senate, etc.) for January, March, May, etc. and his Junior every other month. After his term expired, a Consul became Proconsul and often went to govern an unruly province with a lucrative/dangerous border war, or else perhaps commanded an army on some special job. One Consul could veto the other.

6 Praetors were elected per year (by tradition aged 36 or 38+); the top-polling one became Praetor Urbanus, who dealt with civil and criminal cases between citizens. The Praetor Peregrinus dealt with cases involving non-Romans. The other Praetors assisted them and took on the workload, acting as judges. After his term expired, a Praetor became Propraetor and often went to govern more peaceful provinces. Praetors had considerable influence with each other, but no official veto per se.

2 Aediles (by tradition aged from 31 to 35, 1 Curule and 1 Plebeian) elected per year. I've already described them above. They also hire contractors to do cleaning and repairs on public buildings; the Treasury (depending on who's running it) sometimes foots the bill.

10 Quaestors were elected per year (by tradition aged 30); the top-polling one became Curator/Praefectus Annonae, or Curator of the Grain Supply. He basically lived at Rome's seaport of Ostia, and had to keep in constant communication with ship captains, grain merchants, and the caretakers of the public granaries. The other 9 Quaestors served various clerk/secretarial functions; a Consul-elect or Consul or Proconsul, or--much less often--a Praetor-elect or Praetor or Propraetor, could request a specific man to be his Quaestor, and the electors usually complied. This way, many Quaestors got a good amount of military experience with their secretarial duties, and not a few had to govern provinces and fight wars because of a superior's death.

10 Tribunes of the Plebs were elected per year (aged 30+ with no traditional limit); the top-polling was President of the College, though his role was purely as an agenda-setter, and he had little authority over his fellow Tribunes. The Tribunes suggested and drafted laws ranging on anything from the grain dole to jury composition to a governorship (notably, Quintus Caecilius Senior was stripped of his Proconsular Imperium in Africa by a Tribunal Law, and replaced by Gaius Marius). Tribunes could veto any other magistrate, action, assembly, election, etc.; anything that physically existed, a Tribune of the Plebs could veto it...as long as he was there in person. Thus many a march was sometimes stolen on inattentive Tribunes of the Plebs. The Tribune was sacrosanct, and a man who interfered with his duties (except for another Tribune, using veto) could be immediately thrown off the Tarpeian Rock. This was rarely if ever used; when it got to that point, most Tribunes were too intimidated by their more powerful fellows (they were always at loggerheads) to try a veto.

24 Military Tribunes or Tribunes of the Soldiers were elected per year (aged 24-29); these were the sons of Senators and Equestrians who had the means and connections to serve in the staff of a general of some kind ((Pro)Consul, (Pro)Praetor, any Legate, etc.). Family connections often had a lot to do with this. Since 24 was too small a number to fit the bulging amount of legions serving in the Late Republic, a law came into affect distributing them evenly among generals, and then allowing those generals to appoint their own replacement Tribunes.

Unknown number of Treasurers/Moneyers. It is known that young men about to be Quaestor (aged maybe 27-29), and who had connections or were very good with numbers, would become one of three Supervisors of the Mint. They decided the composition of the currency, and the design on the coins. The Treasurers are more mysterious, and those posts seemed to have been held for life; a governor, upon returning from his province, was expected to give a full report on all assets and transactions to the Treasurers.

Lictors were civil servants, often ex-Centurions, who served as mostly ornamental bodyguards for all holders of Imperium (Curule Aedile, Praetor, Propraetor, Consul, Proconsul, anybody with a Propraetorian or Proconsular command--bestowed by Senate or Plebeian Assembly/Tribunes of Plebs). Lictors received a salary and usually had idle days, though they were often called upon to do various odd jobs.

The Augurs took Auspices at public ceremonies, temple dedications, and convocations of assemblies or meetings (the Senate, all Assemblies, etc.). There was a complex code and varied number of things that could occur (birds flying, lightning strikes, anything) that could be considered "lucky" or "unlucky"; mostly it was all basically made up mumbo-jumbo (like most or all religion, I guess). Augurs often abused their powers, dissolving Assemblies that would oppose them in the name of the gods, through declarations of inauspiciousness.

The Pontiffs guarded the public records, managed the jumbled Roman calendar, wrote down the year's chief events, and served as communicators (the word Pontifex means "Bridge-Builder") to the gods. The Pontifex Maximus was their leader, and he regulated ceremonies, consecrated temples, administered burial, superintended the strictest (conferratio, oldest Patrician) marriages, regulated adoption and family succession, and regulated public morals. Toward the Late Republic, moral sort of fell by the wayside, but regulation of adoption and succession was a powerful political tool. He also had authority over the 15 Flamines (priests) of the State cults (like Jupiter Optimus Maximus, Mars, Quirinus, Ceres, etc.), which all had various duties and restrictions (the main one probably being that they had to collect more money than they spent

This should help, it's basically an outline of their form of government.

tuareg109

Banned

FOR WANT OF THE HAMMER

CLAMORS PART 2, 646 AVC

CLAMORS PART 2, 646 AVC

The loggia of the Marcus Livius Drusus house was huge, as was the rest of the house. Marcus Livius Drusus Senior--and his late father--were known as connoisseurs of fine art and noble extravagance. Six full-grown lotus trees adorned the peristyle garden, brought there by Scipio Africanus, who had owned the house at the time, and they filled the whole house with perfume; genuine bronze statues hundreds of years old by Myron and Lysippus adorned the pool in the middle of the garden; the floor was polished terrazzo, and the walls were painted vividly with greens, blues, and yellows; some of the worlds greatest paintings--by renowned artists such as Zeuxis--hung on the walls; the magnificent atrium, 100 by 60 feet, held another great pool, with life-sized sculptures painted to be life-like surrounding it, and more magnificent paintwork on the walls besides, with eight-foot tall chandeliers illuminating the entire space, for the hole in the ceiling above the pool often did not admit enough light to brighten the walls; and a wide, long, decorated loggia--an open-air gallery.

Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus stood on Marcus Livius Drusus's loggia, leaning against the stone sill and looking down onto his own house below. Marcus Livius's house was often regarded as the best situated in Rome, for it stood on a high spur of the Palatine--the residence of most of Rome's political and social greats--and opened up onto the Clivus Victoriae, which formed part of the path of triumping generals, as well as the path Consuls took to their inauguration. The house, on its high spur, looked down a steep slope over the entire Forum Romanum, the political and legal center of the Republic. Looking a little to the left, one saw the Capitol and the Capitoline Arx, and the magnificent many-stepped temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus, approximately at eye-level; straight ahead was the Senate House and the Well of the Comitia--where Assemblies met to vote and discuss matters, almost hidden by the other Forum buildings; to the right were other temples, the Domus Publica of the Pontifex Maximus, and the Porticus Margaritaria--full of jewels, silks, and other gew-gaws for Roman elites and their wives.

House of Marcus Livius Drusus (32) just to the right of FORUM PISCINUM, and overlooking the House of Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus (33)

So it was that Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus could look down thirty or forty feet and see the loggia of his own house, devoid of people except for the occasional servant scurrying across and cleaning rapidly. Having long been immune to great works of art--he had visited Marcus Livius's house regularly, and in any case was surrounded by it in the house of his father, another connoisseur--his only diversion when his host or his son were not home was to stand on the loggia and look out over Rome. Gnaeus Domitius was under house arrest.

He was treated as an important--if not honored--guest; though no serious attempt was made to keep him inside the house, escape would mean admitting guilt, and that would defeat his purpose, which was to get himself acquitted and somehow use this horrible fiasco to his benefit.

He was very confused as to why he had been put under house arrest. He had gone out to raid Numidia, to gather boatloads of wheat, and to try to even win the war; with this mass of influence and minor scandal he could have breezed to Praetor and then Consul easily, all in suo anno, or the youngest possible appropriate age--a rare feat at any time of the Republic.

There were whispers that he had wanted to lure Quintus Caecilius and Sulla--oh, that enigmatic man! How Sulla had humiliated him, and made him feel like a child! What a lecture (private, thank all the gods)!--to Africa to kill them, or had tried to get his men to mutiny; of course, it wasn't true. That wasn't his style at all. He wanted the influence and the cash to destroy those six men--the five Pontiffs, including his own brother, and the Pontifex Maximus--upon returning to Rome and dabbling in politics, slowly and with relish.

The four legions he took with him did indeed love him, and didn't understand the odium; didn't he act in Rome's interest? Didn't he drive Jugurtha out of coastal Numidia? Didn't he offer them plenty of chances to grab loot on the way? Still, they were propertied men owing little else to Gnaeus Domitius, and so they had--as was proper--immediately begun following the quiet, clearly angry Quintus Caecilius's command.

Not that Quintus Caecilius had blamed the men. No, his ire turned on Gnaeus Domitius in the worst way; he had heard from the wounded Gauda and the white-faced guards what had happened when Gnaeus Domitius heard of his brother's election as Pontiff, and suspected Gnaeus Domitius's motives. So Gnaeus Domitius was packed off to Rome, and informed that some Tribune named Gaius Fulcinius would be prosecuting him. Great, after all that he'd done.

His only--and greatest--consolation was the fact that most Senators would admire his gusto, and that many had been friends or clients of his father; with the courts in the hands of the Senators, he was sure to be acquitted. His thoughts were disturbed by the clicking sounds of heels on the atrium floor, coming his way.

He turned and saw that it was Marcus Livius Drusus Junior, and Quintus Servilius Caepio Junior; though they were some eight years younger than him, he had seen much of both on the Campus Martius as youths, and in the law courts. Because of the ties between their fathers, he knew them quite well. Marcus Livius he had seen much of since arriving in Rome; Quintus Servilius he hadn't seen at all.

"Gnaeus Domitius, Gnaeus Domitius!" Caepio lamented at once. "Look at what that damned Tribune is trying to do to you." Gnaeus Domitius remained silent. "Ah, I can understand your silence; the pain of being betrayed by one of your own class! That Quintus Caecilius would send you off to Rome instead of allowing you to finish out the year under his command is unimaginable."

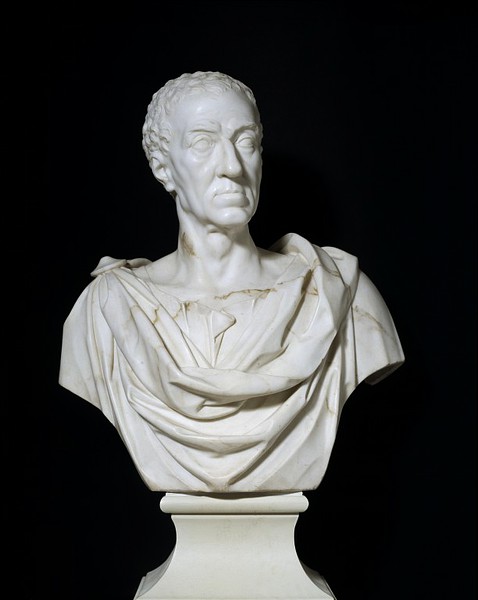

Quintus Servilius Caepio Senior, the father of Junior and his near likeness, in 655 AVC at the age of 51

Having ascertained that Caepio was earnest and sympathetic, Ahenobarbus nodded. "My thanks for your sympathy. I've really got to get to work on my defense."

"Oh, Marcus Livius and I will help you there as much as we can! Isn't that right?"

Drusus Junior made a noncommittal noise, a fact that Ahenobarbus noted. Drusus Junior, though known for being somewhat dull socially, had great legal and political brains about him; this, along with the fact that his father was one of the Pontiffs who had spurned Gnaeus Domitius, meant that he probably aimed to distance himself from Ahenobarbus, if not from the entire affair.

Gazing at Drusus Junior ironically, Gnaeus Domitius said, "I thank you both for your support. It's ridiculous that the jealousy of a select few at my skill in securing so much grain should damage me so much."

Caepio shook with anger. "The--the--the impunity of it! An unknown Demagogue of the Plebs from some Samnite shithole prosecuting a successful, noble Roman general! What's next, that barbarian wins the African war?"

It was May, a month since Gnaeus Domitius had been shipped off to Rome to face charges of treason--helpfully laid by Quintus Caecilius's client Gaius Fulcinius--and Africa Province was again ruled by a Proquaestor. Sulla had woken up two nundinae--about half a month--ago and ventured out to find that Quintus Caecilius Metellus Senior had died in the middle of the night; whether due to stroke, or organ failure, or some other reason, nobody could ascertain. They were camped on the Bargradas, far upriver where the current was strong and the river narrow, and ready to cross the hills into coastal Numidia.

Quintus Caecilius, knowing what his own agents and those of Publius Rutilius had found out, aimed to ignore Gnaeus Domitius's errors--for one could never admit to a foreigner that a Roman had been wrong--and magnanimously forgave the loyal residents of coastal Numidia for ever following the evil usurper Jugurtha. Judging by Sulla's later (partial) success, he would have succeeded had it not been for his death--and one other future event [NO SPOILERS!].

So Sulla was left in command of a surprised--if not demoralized, for they all knew Sulla's skill and care for them--army a hundred miles from its headquarters. He was also in command of an expedition that would fail if he let its momentum stagger at this moment; Gaetuli and other tribal raids in southern Africa had been increasing--Jugurtha was desperate, and Sulla had to strike at the heart of his country to achieve any kind of superiority.

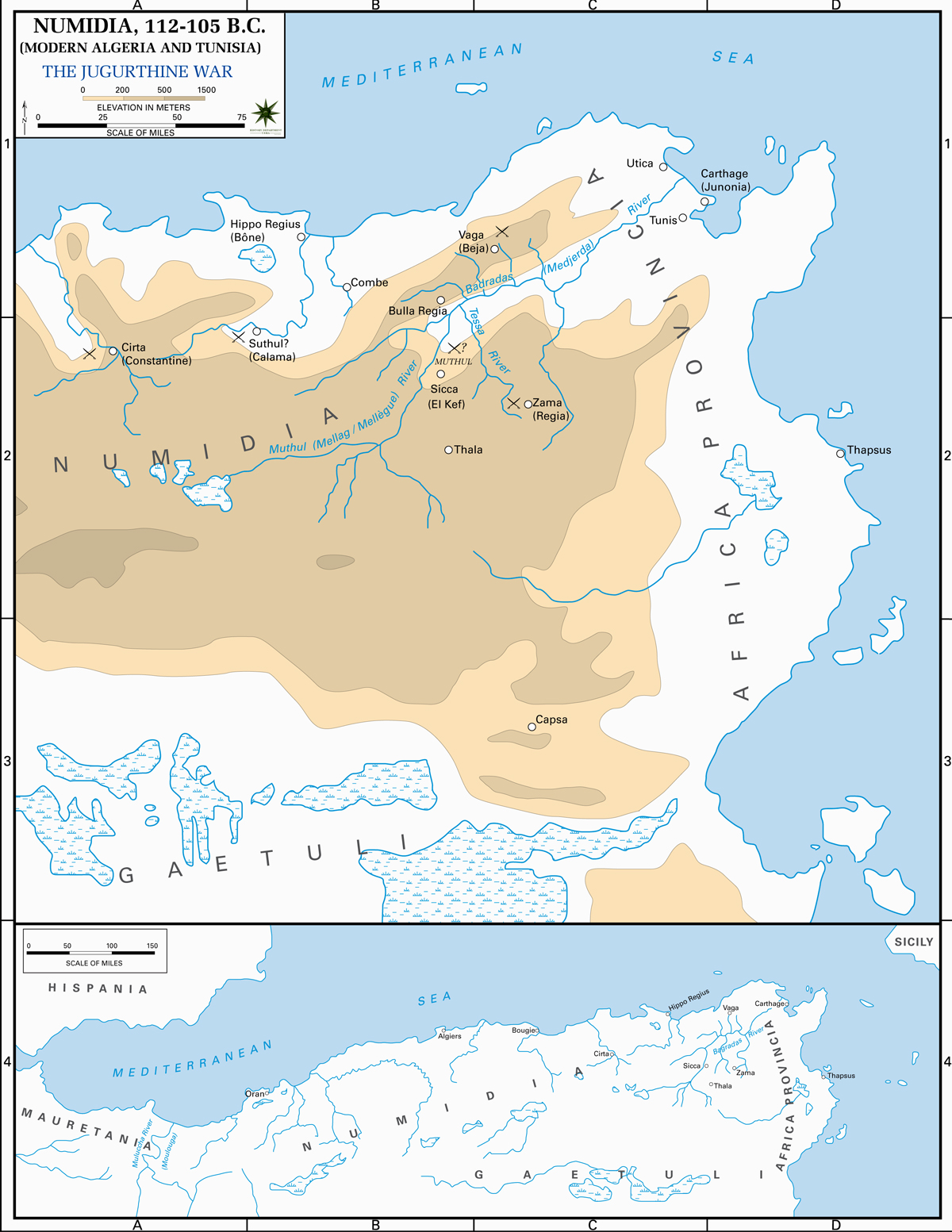

Numidia during the Jugurthine War, 641-646 AVC. Ignore strange crossed swords and confusing "B.C." dates

Sulla knew that, after that idiot Ahenobarbus's debacle, the Senate would act immediately in sending a proper replacement for Quintus Caecilius, and not simply allow Sulla to persecute the war as he saw fit, as it--and the furloughing Quintus Caecilius--had often done before. Ahenobarbus had ruined it for all intelligent, ambitious men left leaderless.

So Sulla didn't send any letters to Utica or to Rome; he could pretend later that the messengers had been caught by raiders and killed, the important letters detailing Quintus Caecilius's death forgotten. It was for Rome's own good that Sulla should command instead of some incompetent Consular--like Hortensius or Galba--looking for latent glory. Luckily enough, he had also intimidated his fellow Legates into allowing him to dictate and send out all dispatches; they would trust him to it, and not bother him. The only two people--both great friends, ironically--who would have caused him trouble were Publius Rutilius (in Rome as Consul) and Quintus Caecilius Metellus Junior--no, wait, he was simply Quintus Caecilius Metellus (Little Piggy/Piglet) now that his father was dead--who was Military Tribune in Gallia Provincia with the Consul Quintus Lutatius Catulus Caesar.

Two nundinae after Quintus Caecilius's death, Sulla was positioned near Cirta. One of Jugurtha's capitals and treasure stores, Cirta was on the cusp between mountain Numidia and coastal Numidia; since any invasion of Numidia was expected to come from the direction of Bulla Regia or Zama, Sulla's army could slide quickly along the coast unseen. And the people of the coast, having not suffered Ahenobarbus's ravages quite like the people just a few miles inland, welcomed Sulla with open arms; his movement along the coast would not be reported to Jugurtha. Nor could Jugurtha's spies survive on the very coast of Numidia; every man in every village knew his neighbor, and outsiders were viewed with extreme suspicion as possibly being Jugurtha's spies. Not a few innocent men had been lynched due to this suspicion, but a few spies had indeed also been killed this way--which, to Sulla, justified it.

For a day now his army--his army, not his superior's!--had been camped a few miles north of Cirta, around a volcanic outcrop that hid them completely from the road. They were capturing everybody that passed along the road nearby, and had learned that Jugurtha was arriving in Cirta tomorrow with his army of 25,000 men. Sulla had with him the four full legions--units had been rearranged, and understrength ones left in Utica for rest and reinforcement--that numbered 20,000 men. Having already been in several battles, and knowing himself to possess that elusive genius of command and charisma with the soldiers, Sulla was confident that he could win.

This was Jugurtha's ground, but Sulla would force Jugurtha to come to him. He would move up into the main road, which winded between the rocky hills--impossible for cavalry or infantry to negotiate in time, so Sulla would not be outflanked--and offer Jugurtha an obvious choice: stay, and fight an even battle on this even ground; or go, and be revealed as a coward, and leave your most important capital city wide open to conquest and plunder. Or Jugurtha could cool his heels in Cirta, supplied well; however, Sulla knew for certain that that didn't suit Jugurtha's personality or style at all. He would venture out for battle.

Sulla, a Patrician Roman, viewed this as no choice at all; Jugurtha felt the same way.

"Damn him, Bomilcar!" Jugurtha was stamping around his tent, punching his right fist into the palm of his left hand. His face was as stormy as usual, but there was something missing. Instead of being angry and regal, as he had been before, he seemed petulant and childish.

Bomilcar shrugged off this shiver of doubt, and said, "Well, we certainly didn't expect him. With Publius Rutilius as Consul, we thought that there were no competent Romans left to oppose us."

"Well, we sure as hell were wrong, weren't we?" Jugurtha spat acidly. "Oh, when will I be rid of these Romans? All I wanted was a peaceful, prosperous kingdom, trading with them. Oh, I admired them so much, Bomilcar! So much. And then Spurius Postumius and those other corrupt shits had to go and ruin it all."

"And Gaius Mamilius, don't forget him. Paid by Spurius Postumius to convict right-minded Romans who wanted to avoid war of collusion with you." Bomilcar gave a wry smile, "Never mind that they were colluding with you."

"Well, and what does that matter when I'm in the right?" raged Jugurtha. "I'm the great king, I'm the great administrator, I'm the great judge; all my 'legitimate'--" he sneered this word "--cousins and nephews and what-have-you combined don't add up to my greatness."

The angry, regal Jugurtha was back. Bomilcar nodded gravely, "I don't deny that, brother."

They were silent for a moment, and then Jugurtha sighed, though he did not look tired at all. "Well, so much for my admiration for the Romans. Scipio Aemilianus must have been the last great Roman; since him, they've only been in a constant decline. Ah, well. Are you ready to kill twenty thousand Romans tomorrow, brother?" King Jugurtha held out his arm to receive the Roman handshake he'd adopted for his own armies.

Bomilcar walked up to him and clasped the offered forearm warmly. "My King, I am ready to kill to you, or to die for you."

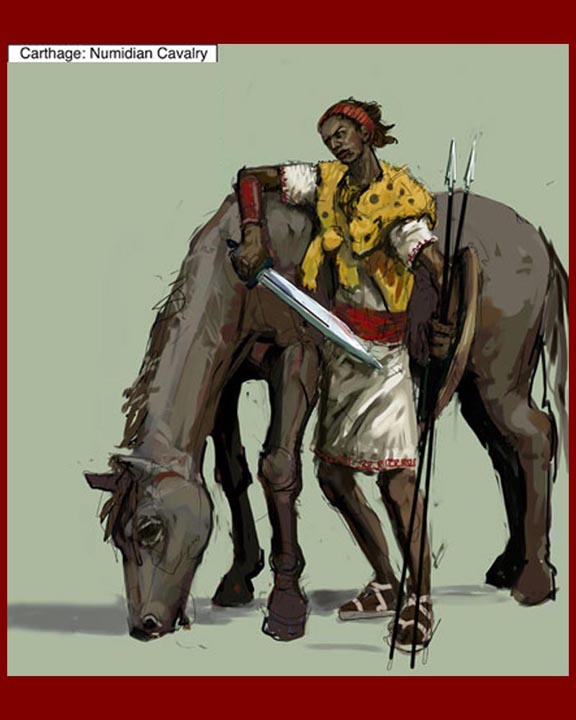

Numidian tribal cavalry, typical of the kind that will be in the battle; this man holds a sword stolen or looted from a Roman soldier

NOTE: That map of Numidia takes about 2 minutes to load well on my notoriously shitty connection; just give it a few minutes

Last edited:

tuareg109

Banned

Tacked a bit on to Sulla's reaction to Ahenobarbus's letter and his actions in Africa and Numidia; also added several tiny fragments (all together in one place) on to Ahenobarbus's section of Clamors Part 2. You get a cookie if you can find the fragments added in Ahenobarbus's section.

EDIT: Wow, I'm going on a long editing spree. Two pictures whose hosting sites have deleted them or malfunctioned or whatever have been replaced.

EDIT: Wow, I'm going on a long editing spree. Two pictures whose hosting sites have deleted them or malfunctioned or whatever have been replaced.

Last edited:

tuareg109

Banned

FOR WANT OF THE HAMMER

THE BATTLE OF CIRTA, 10 Days Before the Kalends of Iunius (May 19th) 646 AVC

THE BATTLE OF CIRTA, 10 Days Before the Kalends of Iunius (May 19th) 646 AVC

Today was the day.

Today Sulla would prove that he was worthy of his birthright. He would prove that he was an adornment to the gens Cornelia, and that he advanced their prestige boundlessly simply by existing. He would whip Jugurtha like a cur, and pursue the war until a peace very favorable to Rome was reached.

The previous day, early in the morning, King Jugurtha, not trusting this unknown Roman, had sent a lowly scribe to negotiate, and it had been agreed upon: the battle would be today, on the honor of both parties. From Sulla's talks with Publius Rutilius Rufus, he knew that Jugurtha could be trusted; the man put much store by honor, which would be his downfall.

Sulla's 20,000 men had been put to work then, sharpening weapons, improving defenses, and training as hard as they could against the day--tomorrow. Sulla had chosen a good spot, well in the foothills of the Tell Atlas range and quite close to Cirta. It was a wide, bone-dry ravine that could fit a legion of men five deep--meaning that it was about 3,000 feet wide--at a particularly narrow point. Sulla had had the Ligurian horse troopers--renowned for their rock climbing skills, for they hailed from the massive Alps and the tall Appenines, mountain-bred and mountain-born--climb up the vertical ravine sides and scout the plateau above. They reported that the land was so broken and covered in deep trenches and fissures, with vertical spires making up the only (barely) navigable terrain, that there was no chance they would be outflanked, or that Jugurtha could position archers up there to rain arrows down on the Romans.

The width of the ravine meant that Sulla could only use a legion at a time, which suited him quite well. Roman armies worked best with the patient grinding technique; and, though Jugurtha's armies were Roman-like, they were not Roman. And that made all the difference, for in Sulla's--quite right--opinion, there was no army in the world more organized and composed as a proper Roman army. With the ravine's width not varying much all the way behind the army, he could simply order an organized retreat for the fighting legion when they got too tired; his men, knowing what to do, would step backwards through their fresh comrades behind them, and go to the nearby camp to refresh themselves. The second legion, completely fresh, would now continue the fight against the Numidians, whose organization wasn't advanced enough to complete this maneuver.

Sulla's main danger would be from the tribal cavalry, who would be able to shoot arrows very accurately into his ranks, and easily gallop away if the Numidian infanty broke and routed...which they would, eventually. For them Sulla had placed a surprise. About 1,000 feet ahead of his position was a tall volcanic outcrop, a black spire rising and leaning into the void of the ravine, looking as if one push would send it toppling onto the road below. What one scout had discovered, by chance, was a long, narrow, secluded recess in the volcanic wall; an optical illusion made it seem like a solid wall from any angle unless you were standing right next to it. Ten horsemen could ride comfortably abreast into and out of this recess, and about a thousand horsemen could fit into the round high- and steep-walled box valley at the end.

Sulla would put most of his horse into this ravine, to wait for the signal to ride out into the valley, and into the Numidian flank. The Numidian horse would wear itself out whooping in circles and shooting arrows into the Romans ranks; Sulla's own remaining horse--for it would be suspicious if he had no cavalry--had in some cases 5 extra mounts each--for the thousand men in the ravine needed no replacement horses--and would use them well, riding fast and hard round and round, raising dust and fooling Jugurtha into thinking that a full cavalry complement was just behind Sulla's infantry, helping to moralize the Romans but otherwise useless.

Sulla's luck had found that hidden corridor into the box valley that would be so useful; he was sure of it. He would have been victorious in any case, but would have lost more men. This way he would slam into the Numidian flank when they were tired and overexerted, having been under the hot sun for hours while his horsemen had been in the shade of the box valley. If they did bring men in the ravine behind Sulla to outflank him that way, he had 3 legions of infantry ready to go there, and one legion could fight on each flank while the two extras rested, and then switched out. It was foolproof.

Initial dispositions at the Battle of Cirta. I am no artist

His only worry was that Jugurtha--being the talented general that he was--would not allow his troops to tire, and would also draw back in an orderly fashion, and then use his cavalry to decimate the Romans with arrows. So he needed something to incense the Numidians--who were not so disciplined, especially the tribes--into attacking as fervently as possible, and ignoring Jugurtha's orders. So he sent the cruelest, most avaricious man he had under his command, a Military Tribune--for the loss of Quintus Caecilius meant that one legion had no Legate--of twenty-eight years named Gnaeus Pompeius Strabo--for his cross-eyed condition--with a legion of men to a nearby town of about 1,000 people the day before the battle.

It revealed much about Sulla's personality, that he viewed the slaughter of 1,000 men, women, and children as justifiable if it won him his battle. He had been scandalized when Jugurtha murdered or ejected all Romans within his borders, but would not hesitate to murder every person in Numidia if it would bring him his victory.

Well, Gnaeus Pompeius and his men had spared no expense. They had murdered the residents of the town and brought them to the front line of the battle; then--it was amazing, thought Sulla, what horrors soldiers would commit when simply commanded to; what power he wielded, in the name of Rome!--they had mutilated the corpses and set them 500 feet in front of the planned front line of tomorrow's battle. Gnaeus Pompeius, who had not gotten quite his fill of blood yet, requested that his legion have the honor of joining battle tomorrow.

In the privacy of his command tent, Sulla said, "I'm sure your men won't like that."

Gnaeus Pompeius, fresh from a quick, inefficient bath and sniffing the blood gathered under his fingernails, said, "My men can go shit, I don't care what they like or don't like."

Sulla's white eyebrows jumped on his red face. "That's no way to go through life, Gnaeus Pompeius. You'll never make Quaestor if certain stories are spread..." he said matter-of-factly.

Gnaeus Pompeius's eyes narrowed as he looked at Sulla--well, to Sulla it looked as if one eye was looking at him and the other high up and to his right--and calculated: is that a threat, or a warning of stories that the men might spread? Gnaeus Pompeius had thought that he'd had Sulla's measure; but now, being alone in the same room with him, he had second thoughts. Those eyes--so unlike his own accursed orbits--hid so much in their pale, pale depths.

Gnaeus Pompeius came from an extravagantly wealthy, but frugal, equestrian family in Picenum. His elder brother Sextus having resolved to continue being an equestrian country-squire like their father, would leave Gnaeus with next to nothing upon their father's death. So Gnaeus had resolved--despite the handicap that his eyes and stocky build presented in the public life of the Roman elite--to serve bravely and viciously in the legions, and be elected Military Tribune through pure merit, and make connections and climb on up from there.

He had been a good subordinate to Quintus Caecilius, and quite a willing accessory to Ahenobarbus's marauding and reaving campaign; now, he had served Sulla very well in this venture. Why should over-zealousness nip his career in the bud? So he nodded assent slowly, as if making a difficult decision--which it was not--and said, "I understand, Lucius Cornelius. I'll tell my men that we were given this honor by you."

Sulla gave one of those deep-throated lunatic laughs of his that so unnerved everybody that heard them, and Gnaeus Pompeius shivered. Is this a man, or a beast? Then Pompeius snapped back to reality and heard Sulla say, "You're not shifting the blame on me, you shifty half-Gaul brute!" That was quite a calculated insult, and it cleaved to the bone; for, despite the Senatorial aspirations of the Pompeiuses of Picenum, they were still descended from the Gauls that had settled there in the 300s AVC, and looked the part, too. Gnaeus Pompeius's mother Lucilia's quite Roman blood hadn't been able to disguise countless generations of pure Gual: He had straw-yellow hair, beady light brown eyes, a very short and very straight nose with a rounded end, wide cheeks, and a big chin. He and his descendant--unless they married pure Roman women every step of the way--wouldn't be rid of these features for at least ten generations.

"I had the feeling," Sulla continued, still chortling, "that would stab me in the back at the first opportunity, and it seems that I was right." Seeing that Gnaeus Pompeius was stunned at this brutal honesty, Sulla laughed all the harder and said, through tears, "Oh, get out of here, do! Tell your men whatever you want!"

Which again left Gnaeus Pompeius so confused that he told the truth: He himself had requested the front line, and fight in the front they would. But not after doing one little thing, in full view of all the Numidian forces. On the morning of the battle they were to close those 500 feet to the corpses of the Numidian townspeople, and kick them, hack at them with swords, and piss on them. This was Sulla's very effective method for raising the ire of the Numidian army, and destabilizing Jugurtha's command.

Battle was joined with the sun just visible over the lip of the ravine, 10 days before the Kalends of Iunius.

ONLY ONE IMAGE? AM I CRAZY?

So...any feedback on this update? I know that it's so much more disjointed and..."out there" than any other update; there's some moving back and forth, and much more simple description. Note: This isn't a permanent chance, but something specific to the description of this battle. I've left the ending as a cliffhanger deliberately, and the result will of course be explored in the next update.

Last edited:

tuareg109

Banned

You've got to host your images on an image hosting site, like imgur, instead of hotlinking them.

I don't have many pictures this time because there's not really a reason for so many.

Yes, it is hosted on imgur. Are you perhaps seeing it differently than me? I see an image..."embedded", I think is the right word, on the page; meaning that I can't click to enlarge or open in another tab, but I can "Save Image As" and "Save URL". Is that right? It looks excellent to me.

Good updates though. I don't think the last one's too disjointed.

Thanks, alright. I didn't know if my description of the field of battle was going to come across very well.

Share: