Conscript Training in the 1920's

Conscript soldiers and women

Up to this point we have studied Finnish conscript soldiers with reference only to military hierarchies and comradeships, the disciplinary methods and strategies of resistance or submission and their army experiences, with almost no reference made to women. This reflects how most men chose to recollect their military service. Their social relationships to women who were important in their lives at the time – mothers, sisters, female friends, girlfriends or wives – are largely left out of the narrative. However, this exclusion is not complete. In brief passages, even mere sentences or subordinate clauses, women are glimpsed now and again. In the 1972–1973 collection, some men mention in passing that they had a girlfriend or a wife either in their home district or in the garrison town. E.g. Kalle Leppälä (b.1913) had a girlfriend and even became engaged to her during his year in military training. He only mentions her existence as if by accident when accounting for the number of leaves of absence he obtained during his service. In his 357 pages of army memories, the longest story in the material examined by the author of this thesis, he writes nothing at all about what the forced separation from his partner felt like, how he coped with it or how they stayed in touch. Eero Tuominen, whose narrative is extraordinary in its emotional openness and articulateness, is an absolute exception, as he describes the longing for his girlfriend after reporting for service, the bliss of spending time with her on his one precious home leave, the anxiousness that she should find someone else while he was gone, and his sorrow and bitterness as her letters grew increasingly infrequent and their contact eventually flagged.

In Mika Waltari’s otherwise so open-hearted army book, the author only mentions the existence of his own girlfriend on page 91. According to Waltari’s autobiography, he met and fell in love with the woman who later became his wife one month before he reported for military service. In Where Men Are Made, however, he never tells the reader anything about her more than that she has blue eyes and a blue hat. It is not clear whether this was to guard his privacy or because he felt she did not really have a place in a book about his military service. Nevertheless, Waltari effectively omits the woman he chose to share his life with, although she evidently was an extremely important element in his life during his military training. He only hints at the happiness of four days on home leave having something to do with being in love, but he is rapturous in describing his return to camp after “a short sad goodbye” from his fiancée. It is ambiguous whether his happiness that night, back at camp, is due to being in love with his girlfriend or with the return to his groupd of soldier-comrades: “I undress in the dark, in the midst of sleeping boys breathing, the familiar smell of foot cloths and boots. Oh, everything, everything is beautiful.”

Seducers, beaux and innocents

An important part of the military culture reigning in interwar Finnish Army barracks seems to have been the repertoire of “naughty” marching songs. These songs ranged in content from raw pornographic and sometimes misogynist imagery to joyful celebration of the mutual pleasures for both man and woman of sexual intercourse. In all of them, however, a self-image of soldiers was cultivated – sometimes soldiers in general, sometimes the soldiers of one’s own unit in particular – as irresistible seducers of women, always on the move towards the next conquest. The soldier’s relationship to women in these songs, sung on heavy marches to cheer up the mood and copied in the soldiers’ autograph albums, was that of a classic Don Juan. This was also the image of soldiers’ relationships to women in popular Finnish films of the 1930’s. Advertisements for military farces alluded to the power of attraction military uniforms had for women. Using military metaphors for soldiers “conquering” women was usual in the screenplays. Recounting their own time as conscript soldiers, however, men gave a much more diverse picture of the conscripts’ force of attraction on women than in the wish-fulfilling fantasies of indecent songs. Some did not mention the soldiers having had any contact with women during their year of Service – apart from the “Sisters” at the service club, who were usually older than the soldiers, extremely highly respected and regarded as sexually out-of-bounds – whereas others mention that dating local women was common among the soldiers.

In these army memories, men do not brag about having been successful among women as they were soldiers. Some point out that it was hard to find female company in a large garrison town, with a considerable surplus of conscripts. An ordinary penniless infantry man had great difficulty competing with conscripts in the artillery, cavalry and navy who had fancier uniforms – not to mention the NCOs and officers with their well-fitted uniforms and golden insignia of rank. The class barriers in interwar society reoccur in some stories about how girls in finer clothes had to be “left to the officers” at a large ball at the theatre of Kuopio in 1929, or how ordinary soldiers from the countryside mainly dated country girls who worked as housemaids in the town houses of Oulu in 1925–1926. Many conscripts seem to have been rather sexually innocent at 21, as mention often is made of “experienced” or “more experienced” comrades, “womanisers”, who told their comrades wild stories about their sexual adventures or were observed with obvious fascination by their comrades. Contacts between soldiers and prostitutes are mentioned in a small number of stories – although none of the informants admit having paid for sex themselves – but they were evidently extensive enough to worry the military authorities, because of the spread of venereal disease. In this regard, the military system sent the conscripts a double message; the military priests demanded self-restraint and abstinence, lecturing the soldiers on the irresponsibility, filthiness and devastating effects on future marital happiness of contacts with prostitutes. The army medical service, however, took a more pragmatic approach, instructing conscripts who had sexual intercourse during leaves to visit the hospital when they returned for preventive treatment. Concealing venereal disease was punishable.

Mika Waltari, who was the most enthusiastic describer of warm and close comradeship among male soldiers in the author’s material, is also the only one to write at length about the significance of women within the military. His soldiers talk and dream about women when they are in camp and they eagerly date girls when they are back at their town barracks in Helsinki. However, women appear as distant and exotic in this world of men. To some they are creatures to be pursued, seduced and conquered, big game to brag to one’s friends about. Yet to Waltari and his close friends, who are middle-class and with a “good upbringing”, they are above all associated with a vision of the future, of marriage, of emotional satisfaction and security in a stable partnership. One night in camp, Waltari and his comrades lie around talking shyly about these things. “Of course we could talk and brag about the most incredible erotic adventures we have had, which are more or less fantasy. In fact most of us are very innocent, in the dangerous borderlands of manhood. Now that we are healthy and a new strength is growing in our limbs, we all feel distaste for brute erotic looseness. A dark night in some bushes or naked hostel room would be a heavy fall for us. Now that we have something to give, we want to keep ourselves pure – that same word that made such an irritating and banal impression in Christian morality lectures. Now we want to some day, when our true moment has come, give our whole strong youth. Get engaged and married when that time comes. In all of us glitters the beautiful illusory dream of a home of our own. Without our knowing, we are growing closer to society. Free, unfettered youth and the social system are always each other’s enemies. But here, through submitting, a deeper and greater solidarity has unconsciously been impressed upon us.”

In the depiction of this scene, Waltari reproduces an image, familiar from the storys by middle-class men writing in Suomen Sotilas, of conscripts as “pure” young men, living a stage of their lives centred on the community of conscripts, predestined although not yet ready for marrying and heading a household. This image was actually a vital precondition for the notion that the army was the place ‘where men were made’. If the recruits were already living in mature relationships, they would already have been real men and military training could not have been legitimised by claiming it brought them into this state of being. Waltari also makes an association here between submission, military service, becoming a loyal, responsible and useful male citizen, and getting married. Soldiering and fatherhood – in the sense of being responsible for a family of one’s own – thus join each other as two significant currents taking the young man towards adult, mature manhood and patriotic useful citizenship. The silence around marriage and serious partnerships in the other sources does not mean that they were not an important among the lower classes as well. In Pentti Haanpää’s army book, this is only hinted at through a few clues in his stories, yet in analysis it emerges as a key factor behind Haanpää’s criticism of military life. The Jäger sergeant major in his opening story not only goes home to take over his family’s little farm, as previously cited. He “fetches” a girl from the garrison town to live and form a family with her. She is not mentioned before the third to last sentence of the whole story although the Jäger evidently has had a lasting relationship with her. Haanpää lets the reader understand that the Jäger eventually finds a fulfilment that army life can never give him in a classic rural Finnish lifestyle based on marriage, fatherhood, land ownership and productive work. Twice he uses the word “barren” to describe the gritty military training fields, implicitly contrasting them to the proper place of a Finnish man, a field of corn or a timber forest where his labour bears fruit.

One explanation for the omission of girlfriends and wives in army stories and memories might be the habit of “undercommunicating” one’s marital status that ethnologist Ella Johansson has noted in the barracks and working camp culture of Swedish mobile workers in the early twentieth century. Being married and thus head of a family was strongly a part of the ideal for adult men. Yet this was played down among the workers, together with social and economic differences, in order to create a conflictfree atmosphere (one might say an illusion) of equality between men. This would seem to apply to both army barracks culture and the narrative tradition stemming from it. Sexual adventure with women was over-emphasised in army stories, whereas serious commitment with women was under-emphasised.

Finally, the silence of most men on what it was like being separated from one’s mother, sisters and possible female partners – sometimes for a whole year without a single home leave – should probably also be understood as informed by the narrative tradition of commemorating military service. This tradition was reflected and reproduced by the ethnologists organising the 1972–1973 collection. Among the more than two hundred questions they asked their informants, the only one touching upon the existence of women in the conscripts’ lives was a subquestion’s subquestion, under the topic of how evenings off-duty were spent in the barracks: “Was alcohol ever brought into the barracks? What about women?” The otherwise exhaustive questionnaire omitted any references to how the soldiers’ families related to their departure; if and how the conscripts stayed in touch with their families during the service; how they took care of possible problems arising at home due to their absence; or what home-coming was like. These subjects evidently did not belong to the story of a military experience shared by all conscripts. In a sense, leaving out women from the story of Finnish soldiering had a similar effect of strengthening the taken-for-granted notion that women and military matters had nothing to do with each other.

Conclusions: Class, Age and Power in Conscript Stories

Memories and stories about military training in the 1920’s show that popular images and notions varied and partly contradicted the pro-defence viewpoint. Many depictions of the disciplinary practices in use lie closer to the critique of the cadre army delivered by Social Democrats and Agrarians in the period, although men who recounted their own experiences of military training did not subscribe to the notions of its morally corruptive effects on conscripts. Class and age affected how men’s army experiences were formulated. Comparing Pentti Haanpää’s and Mika Waltari’s army books, the contemporary class divisions and politics of conscription serve as an explanatory pattern for the differences between them. From the vantage point of the 1970’s and old age, other men mixed the polarized interpretations of the interwar period into a kind of synthesis that did not serve the purpose of defending or criticising the cadre army, but of crafting a part of their own life-history.

Through his description of military comradeship, Mika Waltari conveyed an image of Finnish conscripts as boyish youngsters, blue-eyed boy scouts on the threshold of manhood and adult life. This was a prerequisite for the notion that military training could project them on a path to a higher level of being, to mature citizenship. That effect gave a positive meaning to the hardships they had to endure along that path. Through forming a community of comrades, a brotherhood-in-arms, Waltari’s citizen-soldiers supported and spurred on each other to learn and train for the task of men, defending the country. At the same time they were taught the self-control and unselfishness needed to submit. This experience, Waltari claimed, endowed conscripts with the self-confidence to face adult manhood with its responsibilities. The effect of Waltari’s narrative – whether it was his intention or not – was to defend the cadre army system by offering an attractive solution to the paradox between adulthood and submission, and claiming that it only changed men for the better.

Pentti Haanpää, on the contrary, suggested an image of Finnish conscripts who were no compliant young boys when they arrived for military service, but rough-hewn adult workmen. Military training had no personal value for them, and without a war to fight the hardships and humiliations involved appeared to them as meaningless sadism and oppression. Haanpää’s soldiers felt offended by military discipline and reacted by resistance and recalcitrance in any form available – shirking, cheating and lying. Haanpää had no use for the sedative notion of supportive comradeship that lessened the strain of life in a cadre army. In his portrayal, comradeship was more about an inflicted life together. He did not attempt to idealise military comradeship or even describe the conscripts’ ways of being men as particularly sympathetic. The message emerging from his stories was rather that this was what common Finnish men are like, like it or not, and if the cadre army system stood in contradiction to it, the military system had to change. To Haanpää’s workmen, the army was an oppressive interruption robbing them of autonomy and dignity, but to Waltari’s middle-class students it offered an opportunity to boost their white-collar self-image with the prestige of being not only warriors, but also the military leaders of their generation. Waltari wrote in the “white” tradition, describing an affinity between men in military service, united across all other differences by gender, nationality and soldiering. Haanpää’s images of soldiering were closely aligned with the political critique of the standing cadre army as an institution corrupting men, both through the oppressive violence of a detached officer caste and through the roughness of comradeship in the “unnatural” circumstances of men living isolated from society in an all-male military hierarchy.

These differences are interestingly congruent with those between the ‘modern’ middle class and traditional rural and working class views. Industrialisation and urbanisation, it has been argued in previous research, robbed the middle-class of its traditional stable foundations: landownership or autonomy as a self-employed artisan. In the emerging modernity, every middle-class man had to prove and demonstrate through “making himself” in the fierce competition of the marketplace. This notion of a need to demonstrate an ability that was not inherited as a social position from one’s father is strikingly similar to Mika Waltari’s eagerness to demonstrate that “he can make it where the others do”. Pentti Haanpää’s conscripts, on the other hand, navigate within a largely rural value system where great value is put on the autonomy based on controlling one’s own labour. The soldiers depicted by Haanpää try to claim a degree of self-determination by using strategies of obstinacy and wilfulness, similar to the contemporary culture in teams of male workmen, for example in forestry or railroad construction, as described by Ella Johansson.

The culture of shirking and malingering could also be conceptualized as Eigensinn, a term that Alf Lüdtke has used to describe how contemporary industry workers on the continent temporarily distanced themselves from the hierarchies and demands of the workplace, refusing co-operation and gaining some sensation of pleasure through teasing fellow workers, walking around, talking to people, taking unauthorized breaks or just daydreaming; anything one was not supposed to do during working hours. Eigensinn or wilfulness, as outlined by Lüdtke, is thus not a form of resistance against the system, but rather attempts by individuals to temporarily ignore or evade the system, to create moments and places of independence from and disregard of the surrounding social order, insisting on time and space of one’s own. Conscripts displaying Eigensinn thus did not necessarily want to challenge or change the military system. Rather, they needed some space to breath within it. In spite of the variations and differences across the 1972–1973 reminiscences, and the evident development towards better treatment of conscripts over the course of the interwar period, the collection as a whole reflects many experiences of military discipline, especially during recruit training, as containing elements of meaningless harassment reminiscent of Haanpää’s imagery. The explanations offered for superiors’ bullying, in terms of NCOs and officers taking out their personal frustrations and aggressions on their subordinates, are also in line with Haanpää. Yet none of the men who wrote about their military training after the Second World War really attacked the pre-war cadre army system in the same wholesale fashion as Haanpää. The cadre army had proven its worth in the war, and even if some men expressed bitterness over how they had been treated and wanted to expose the power abuses that had occurred, the general tenor in 1972–1973 was that interwar military training in its very hardness was necessary and useful.

Since it was not necessary any more to either attack or defend the institution itself, the stories written down in the 1970’s are actually less black-and-white than the interwar literary depictions. They needed neither the demonising story about an officer corps rotten throughout, nor the idealised myth of conscript soldiers’ unreserved solidarity and comradeship. Accounts of bullying and sadistic superiors could be accommodated in the same narrative with very appreciative descriptions of well-liked officers. Good comradeship and group spirit were mentioned in the same breath as violent conflicts among the conscripts were revealed. In the final analysis, many former soldiers evidently adopted the notion of military service as “a school for men”, a place where conscripts grow, harden and develop self-confidence through the very hardships they suffer, in order to invest a largely disagreeable or partially even degrading experience with a positive meaning. However, they did not idealise submission in itself nor the collectivist fusion with the group as Waltari did; theirs were individualist stories of their ability to cope.

Historian Thomas Rohkrämer has found the same pattern of a “growth narrative” surrounding nineteenth century German military service. The training, Rohkrämer claims, was intentionally laid out with an extremely hard and even humiliating recruit training in the beginning followed by slowly ameliorating circumstances. Once the soldier had adjusted to army discipline and taken on the behaviour his superiors wanted, he could enjoy certain rewards; a high social status in relation to civilians, an economically carefree existence, and a boosted attractiveness with women due to the “military bearing” and the gaudy uniforms of the epoch. Rohkrämer asks why so many men rallied round the cult of the military in the Kaiserreich and offers the explanation that military service was understood as an initiation that was accepted and celebrated afterwards. Once the hardships of military training had been endured they could reap the benefits from public notions of men with military education as characterised by energy, vigour and resolution.

From the early 1930’s on, a political consensus over the military system gradually emerged. As we have seen, the conscript army of independent Finland started out with severe image problems. Some of these were inherited from the standing armies of the authoritarian monarchies that served as organisational models for the Finnish cadre army. Other problems burdening the Finnish Army derived from the fact that it had been created in the midst of a civil war where its main task was to crush an internal socialist revolution. This initial ballast was further exacerbated through reports of the bad conditions that conscript soldiers were exposed to throughout much of the 1920’s. The pro-defence debate in interwar Finland must largely be understood against the background of widespread negative images of the existing military system. While pro-defence advocates made great efforts to disseminate positive images of military service, they had to compete with popular notions of the conscript army as a morally and physically unhealthy place for conscripts, as well as a culture of story-telling about personal experiences of military training that often highlighted the brutal treatment and outright bullying of conscripts.

Military service was described as strongly formative of conscripts’s physical and moral development, both by the critics and by the supporters of the existing military system. As the military system became a part of cultural normality, as the worst conditions were corrected, and as people grew accustomed to conscription and increasingly came to accept it – although not necessarily to like it – there was less need to talk about its impact. However, this was more the case in the political arena and the ideological propaganda of “civic education” than in the popular culture of telling stories about individual experiences of military training. Even if the notorious bullying of conscripts obviously diminished over the period, men still found personal use for the claim that going through a harsh and demanding training had made a positive difference to their personal life history.

Analysis of the parliamentary debates over the conscription system shows a prolonged scepticism and reluctance within civilian society towards the conscription system created by professional officers during the Civil War. There was a swift transition during the Civil War from widespread pacifism and doubtfulness over the expediency of any national armed forces towards a broad acceptance of the general principle of conscription. The need for maintaining a Finnish army was no longer disputed. However, peacetime military service within a standing cadre army was initially criticised by the parties of the political left and centre. They drew on a long international tradition of republican, liberal and socialist critiques of standing armies. The liberal and conservative MPs, on the other hand, were conspicuously restrained as they presented the existing military system as a grim necessity. They largely refrained from celebrating any character building effects of military service. In spite of their glorification of the feats of the White Army in the “Liberation War” of 1918, politicians at the centre and right were wary of expressing any opinions that could be labelled as militarist. They were susceptible to public concerns over bad conditions in the garrisons and the maltreatment of conscripts and throughout the 1920’s resisted the military’s requests for more money and increased conscripted manpower.

Those politicians who wanted a people’s militia centred their critique of the cadre army on its alleged moral dangers for conscripts and the threat to democracy of a closed caste of professional officers. However, their reasons for doing so evidently had much to do with other issues of a political and economic nature; namely, the control over the armed forces in society, the enormous costs of creating and maintaining national armed forces, and the importance of conscripts in the workforce of a poor and largely agrarian society. In their rhetoric can be identified references to both idealised images of the Finnish national character and visions of egalitarian citizenship in the new democratic republic. The Agrarians alluded to a stereotype of Finns as autonomous freeholders, with a natural patriotic instinct to defend their property and families, yet averse to authorities and submissiveness. The Social Democrats expressed a more anxious notion of working-class men as susceptible to indoctrination and political corruption through military service. Nonetheless, they simultaneously tried to describe young workers as class-conscious, strongwilled men who would fight only for the good of the people and not the for the bourgeoisie.

Over the course of time, the parliamentary debates demonstrate a slow movement from strong scepticism towards acceptance of a conscripted standing cadre army; from strong notions that such an army could form a threat to democracy towards embracing it as a safeguard of the democratic republic; and from intense concerns that army life would corrupt conscripts towards confidence that it would at least do them no harm. One objective of the interwar commemoration of the “Liberation War” was to portray a view of the recent past that supported interwar patriotic mobilisation and military preparedness and counteracted the scepticism and reluctance surrounding the conscript army.

The heroic stories about the Jägers conveyed images of the Finnish nation as ready for action, notions that national freedom and prosperity were based on military force and valorous heroism, and a message of the invincible strength of passionate, self-sacrificing patriotism. According to the heroic stories, the Jägers were zealous young warriors, driven by flaming patriotism and antithetical to old-school aristocratic officers, such as the older and more experienced Finnish officers who had served in the Russian army before the war. In the campaign to oust “Russian” officers from leading positions in the armed forces, it was claimed that the Jägers represented a new kind of officer, capable of motivating and filling conscripted soldiers with enthusiasm for military service and patriotic sacrifice. The Jägers of heroic stories were living examples of a Finnish military readiness that was now demanded of every young conscript in order to secure national independence. The national-warrior attitude to soldiering incarnated by the Jägers was made the objective of the military education of conscripts – with Jägers as models, planners, executors and leaders. Military thinkers within and associated to the Jäger movement claimed that Finland’s military and political situation demanded soldiers who had received a moral

education instead of being drilled into mechanical obedience. These “new” national soldiers had to be strong-willed soldiers, motivated by patriotism, self-discipline, a sense of duty and a spirit of sacrifice. Moreover, they had to be led by officers embodying these same virtues to the highest degree; officers like the Jägers themselves.

The project of idealistic officers and educators to morally train a “new” kind of Finnish citizen-soldier was put into concrete form with the project of giving the conscripts a “civic education”. The magazine for soldiers, Suomen Sotilas, used the rhetorical technique of associating the wished-for, well-disciplined citizen-soldier with strength and courage in an attempt to influence the readers’ self-understanding and behaviour. The magazine offered its readers images of military training as a process where conscripts matured into adult citizens marked by vigour, a sense of duty and self-restraint. Acquiring the skills and virtues of a good soldier, the young man would simultaneously develop into a useful and successful citizen. The hardships he had to endure would be meaningful and rewarding in the end, both for the nation and himself as an individual.

The magazine wrote abundantly on Finnish military history, challenging the readers to honour their forebears’ sacrifices and meet the standards set by previous generations, but also reassuring present-day conscripts by conjuring a sense of sameness, affinity and a shared national character, marked by hardy, valorous and unyielding character among Finnish men in both the past and present. However, the notion that army life could be corrupting of conscripts’s morals was also surprisingly conspicuous in the magazine, mainly in storys written by clergymen. These “moralist” writers obviously regarded “false” notions among the young conscripts as a great challenge to their educational project and attempted to push their own definitions of true character, centred on self-restraint and dutifulness.

Finally, this study has contrasted the official rhetoric surrounding conscription with the stories that conscripted men told about their personal experiences of military service. The analysis of Pentti Haanpää’s and Mika Waltari’s accounts of military service connected the stark differences between them to both contemporary political disagreements over conscription and the class background and social prospects of the men they served with. As demonstrated by Haanpää,

Waltari, and the collection of reminiscences written in 1972–1973, the social practices of military service in the 1920s were often divisive as they confirmed the class hierarchies and political conflict lines in civilian society. Educated young men such as Mika Waltari were confirmed in their consciousness of belonging to the nation’s elite. They were given an opportunity to prove their physical fitness and leadership qualities. Men from working-class environments, on the other hand, could find that disciplinary methods perceived as bullying and harassment confirmed their understandings of the “white” army and capitalist state as oppressive of lower-class men. Most men did not find much use for the trope of military comradeship in their army stories. It was important to Mika Waltari in his construction of military service as a development process within a tightly knit collective, but not to either Pentti Haanpää who attacked the military system by portraying it as corrupting human relationships, or the men writing down their memories of the army in the 1970’s, who essentially wanted to tell a story of their individual ability to cope and their personal development.

As this analysis has shown, the images of soldiering in oral popular culture largely contradicted the loftiness of military propaganda. These popular images underscored the hardships and abuses that conscripts had to endure. Superiors’ incessant shouting, formal and distant relationships between officers and men, exaggerated emphasis on close-order drills, and indoor duties such as making beds and cleaning rifles, gratuitous punishments and widespread bullying of subordinates – these were all central elements of a “dark story” about soldiering especially in the 1920’s. Even those with positive personal memories indicated an acute awareness of these negative popular images. It was usual to ascribe seemingly meaningless harassment to “Prussian” military customs unsuitable in Finland and ineffective on Finnish men. Individual superiors prone to bullying could be disparaged as weak in character and lacking real leadership qualities. Another strategy was to belittle and play down the harassments as only “proper” to military life and something a man could take with good humour.

The dominant narrative form in the army reminiscences was, however, to construct the story about soldiering as a process of personal growth, through hardships and even humiliating experiences, towards selfconfidence, independence and adult citizenship. Here, the rhetoric of military propaganda and popular stories met. Although the origin of this narrative model is uncertain, military educators and army authorities undoubtedly worked hard to repeat and reinforce it in official military ideology. Yet to the extent that men accepted this offering of prestige and recognition in exchange for their allegiance, they put it into the much bleaker constory of their own experiences of hardships, conflicts and bullying. Thereby, they maintained a counter-narrative to official images of soldiering. The fact that politicians and military educators abstained from playing on language nationalism in their rhetoric on conscripting conscripts is more intriguing. In a sense it is natural that national defence would be a constory where national unity was emphasised and internal differences in domestic matters were downplayed. Yet as we have seen, internal class differences did push their way into debates on conscription and even military propaganda. In this particular constory, the class divide was evidently deeper and more poisoned by mutual distrust than the language divide. In the wake of the Civil War, it was perhaps easier to imagine a national community of “white” Finnish- and Swedish-speaking soldiers once more defending the country against the Bolsheviks than to imagine the workers and the bourgeoisie as brothers-in-arms united in valorous patriotism.

Modernity and tradition

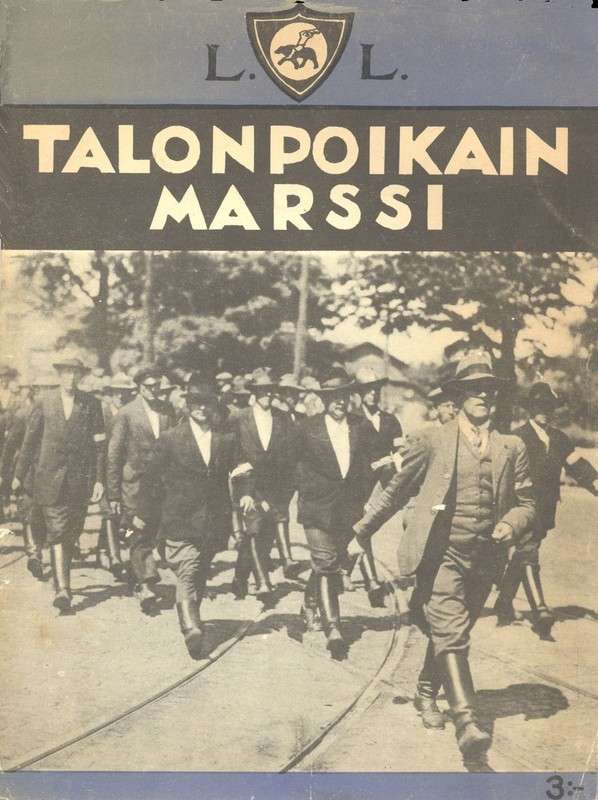

The mass parties of the political left and centre at first associated the standing conscript army with authoritarian, warlike monarchies of the past, an insular aristocratic officer caste and oppressive treatment of the rank-and-file. The Social Democrats and Agrarians saw the cadre army as an obstacle to democratisation and antithetical to a new era of equality, social progress and societal reforms - the kind of modernisation they themselves envisioned. In the Agrarian’s arguments for a militia, no need to change or modernise Finnish men was expressed. On the contrary, they argued against the cadre army by celebrating a timeless masculine national character, an inherent aptitude for warfare in Finnish men, which they claimed had been proven once again in the Civil War of 1918. The Finn’s love of freedom and fighting spirit would only be stifled and corrupted if he was incarcerated in barracks and drilled into mechanical obedience by upper-class officers. In a people’s militia, on the other hand, soldiers would remain inseparable parts of civilian society, mainly occupied with productive labour and impossible to corrupt morally or politically. In their own vision of social progress, the Social Democrats hoped that conscripts would form part of a politically self-conscious workers’ movement that would force through a modernity marked by social justice. The cadre army system threatened to put a check on that movement by defending capitalist interests and drilling young workers into compliant tools of the propertied classes.

The war hero cult surrounding the Jägers, as well as the military propaganda aimed at giving the conscripts a “civic education”, included powerful images of the “Liberation War”, marking the dawn of a new era of Finnish military. The heroic stories about the Jägers supported notions of the brand new national armed forces as representing something new and progressive in Finnish society. They powerfully associated the “liberation” of Finland from Russia with a national “coming of age” manifested in military action. Military reformers wrote about a “new” age of warfare that needed strong-willed, self-propelled and self-disciplined soldiers who fought for their nation out of their own free will and patriotic conviction. In nationalist propaganda, the Jäger officers were constructed as a “new” kind of youthful and modern military leader who could fulfil the moral and technical requirements of a new era. The military propaganda directed towards conscripts in training strongly connected this “new” military image with citizenship. Military training was supposed to educate the conscripts for modern citizenship. This not only included preparing for defending the new nation and enduring the horrors of modern warfare. It also meant acquiring the energy, discipline and precision that characterised a member of an industrialised civilised nation. The army was ‘a school for men’ – the kind of men that the new Finland needed.

.

The stories of men who did their military service in the 1920’s testify that the “corporal spirit” criticised as old-fashioned and dysfunctional by contemporary military educators was alive and well in the Finnish armed forces. The “dark stories” about tyrannical superiors browbeating the conscripts resonated with critical claims about the questionable ideological and moral impact of this particular military training on conscripts. Their persistence through much of the 1920’s was highly problematic for those who wanted to represent the cadre army as part of national modernity and progress. The literary scandal surrounding the publication of Pentti Haanpää’s Fields and Barracks in 1928 provides an ample illustration of the frictions between those in Finnish society who hoped the army would change Finnish men and those who thought the army itself was the problem, not the solution. The press reviews deserve some attention, since they present us with a condensed picture of how conscription was connected with conflicting visions of modernity.

The socialist press lauded the book as a truthful and realistic depiction of army life from the perspective of ordinary soldiers. The non-socialist press, on the other hand, greeted the book with dismay. The magazine of the Civil Guards, Hakkapeliitta, accused Haanpää of downright lying, “poisoning young souls” with mendacious and coarse rubbish. The reaction it evoked in the pro-defence establishment was summarised in the headline of an editorial in Suomen Sotilas: “A desecration of the army”. Yet many book reviews and commentaries in the centrist and conservative civilian press also admitted that there was some truth to Haanpää’s stories. There were nuanced comments made, for example by the military philosophy teacher Hannes Anttila, about undeniable deficiencies in the conscripts’ conditions and the need for officers to read Haanpää to understand some of their conscripts better. Still, the non-socialist press claimed that Haanpää had limited his description to only the bleakest and gloomiest aspects of military life. It was said that he lacked self-criticism, “true education” and the analytical capability of putting his observations into a larger constory. Professor V.A. Koskenniemi, one of the greatest literary authorities of the era, dismissed the book as “sketch-like minor art” and noted that Haanpää’s laudable prose was tainted by the cheap trick of “boyishly defiant exaggeration”.

To many non-socialist reviewers, the types of men Haanpää portrayed seem to have been a greater concern than his images of the bad treatment of conscripts. The conservative newspaper Uusi Suomi criticised him for having identified himself with “the worst and most immature sections of the conscripts”. An editorial in Suomen Sotilas claimed that there was a minority among the conscripts who lacked “a clear understanding that military service is not meant for pampering and enjoyment, but a severe and difficult school preparing for war”. These elements among the soldiers, wrote the editors, were “morally often quite underdeveloped, unpatriotic, even criminal”. A columnist in the agrarian Ilkka newspaper branded Haanpää’s book as mostly expressing “hatred of lords and masters” and its author as “one of those men still serving in the army who are impossible to educate because they do not comprehend what it means to be under somebody else’s command”. The critic Lauri Viljanen wrote, “In accordance with his nature as a writer [Haanpää] feels the greatest sympathy for those individuals who find it the hardest thing in the world to grow accustomed to any form of societal discipline.” These reviews implied that beyond some fine adjustments, it was not the military system that needed fundamental change. Haanpää’s obstinate conscripts were the ones that really needed to be thoroughly reformed. They were seen as remnants of a primitive Finnish society of isolated villages, characterised by wilfulness and a smouldering hatred of any authority, unable to adjust to a new and changed society and citizenship.

On this point, the young modernist author and critic Olavi Paavolainen was the most outspoken, as he reviewed Fields and Barracks for Tulenkantajat (The Torchbearers), a cultural magazine and mouthpiece of young artists oriented towards Western European culture and modernity. Paavolainen had done his own military service at about the same time as Haanpää. He found Field and Barracks “disgusting” because its author never rose above “the same low and unintelligent level of thinking and feeling” inhabited by the human types he depicted. Since Haanpää was no town dweller, but “the disciple of untamed conditions” – i.e., underdeveloped rural regions – he lacked “the intellectual and theoretical passion to solve problems”. Nevertheless, Paavolainen asserted that “anybody who has served in the army can testify that the majority of conscripts think and feel like Private Haanpää”. Yet he continued, “How one learns to hate [the Finnish] people during military service! Not because it is supine, incapable and slow, which qualities are offset by its honesty, tenaciousness and toughness – but because it has an insurmountable dread of any order, regulation and – without exception – any commands. It holds resisting any instructions as a matter of honour. (…) This desire for recalcitrance expresses a basic trait in the Finnish national character.”

Paavolainen thus actually agreed with Haanpää’s description of Finnish men and their reactions to military discipline, but saw the reason for their mentality not in some deep-rooted folk culture, but in nineteenth century nationalist agitation by the educated classes. The Finns, he wrote, had always been told in speeches and historical works that their hallmark was not to obey orders and not to accept the yoke of any masters – because these masters had always been foreign. The notion that every command and all lords and masters were bad things had been impressed upon the Finns by both national romanticism and socialism, claimed Paavolainen. It was time for Finnish men to liberate themselves from “the idealisation of a nation of virginal people living in the wilderness and a national culture of lumberjacks”, replicated by Haanpää. Paavolainen saw the cure in modern military training: “Look at the boys who come home from the army: how differently they move, walk, talk, eat and think. Their brains, used to executing orders, work keenly, their bodies shaped by exercises and sports are lithe and obedient. In them is the stuff of a modern civilised nation. Military service has been a first-rate school. (…)”

For want of anything better, Paavolainen found military training to be an excellent instrument for implanting a notion of “a new rhythm of life” in the Finnish people. Life in the modern world, he wrote, with its “telephones, offices, newspapers, street traffic, universities, radios, sports, transatlantic liners, train timetables and stock exchange news” was impossible if people had no concepts of discipline, exactitude and timetables. In the wake of the traumatic events of 1918, optimistic and idealistic visions of the Finnish citizen shaped by military training held out the promise that such military training would defuse the threatening revolutionary potential in Finnish men from the lower classes and mould them into self-disciplined, dutiful, patriotic soldiers ready to sacrifice themselves for the nation. Their sense of comradeship with their fellow soldiers from all layers of society would ensure their loyalty to the existing social structure and direct their armed force outwards, towards a common enemy. The Jäger myth displayed how the dangerous passions of youth could be channelled and disciplined through nationalism and military training into a force that had a burning zeal, yet protected existing society against inner and outer foes instead of threatening it. The editors of Suomen Sotilas assured their readers that when the well-trained and self-disciplined citizen-soldier returned from the barracks to civilian society he was indelibly marked with characteristics that would support the nation’s progress towards modernity and prosperity without internal strife.

Yet a neat dichotomy cannot, after all, be made between a modernist middle class supporting a thorough re-education of Finnish men in the fields and barracks of the cadre army on the one hand, and recalcitrant peasants and workers resisting change on the other. The same circles that envisioned the military producing patriotic and useful male citizens often – whenever it suited their purposes – referred to the heroic national past, military traditions and an inherent unyielding bravery and coarse fighting skill in Finnish men. For example, the Jägers stood for the new nation and its ideal citizens, but in their strong and bold manliness also evoked memories of the Finnish forefathers, linking the modern nation to a mythical past. “The spirit of the forefathers” was presented as binding obligation on conscripts to show that they were not lesser men.

On the other hand, the political opposition and resistance to the cadre army and prolonged peacetime military service were not necessarily based on an opposition to modernity or modernisation as such – although Pentti Haanpää did idealise an archaic, agrarian way of life. Social Democrats and Agrarians also wanted progress into modernity, only they each had different visions of what kind of modernity was desirable for Finland. Neither of these parties really resisted the militarisation of Finnish manhood, although conscription would have looked very different if the militia army they proposed had been realised. The militia project expressed another view of the relationship between a man’s task as a soldier and his task as a productive peasant or worker, a son, a husband or a father, where only open war was reason enough to tear a man away from his proper and primary places as a man. In this sense, the militia model implied a weaker polarisation and separation of male and female citizenship than the cadre army model that was realised.

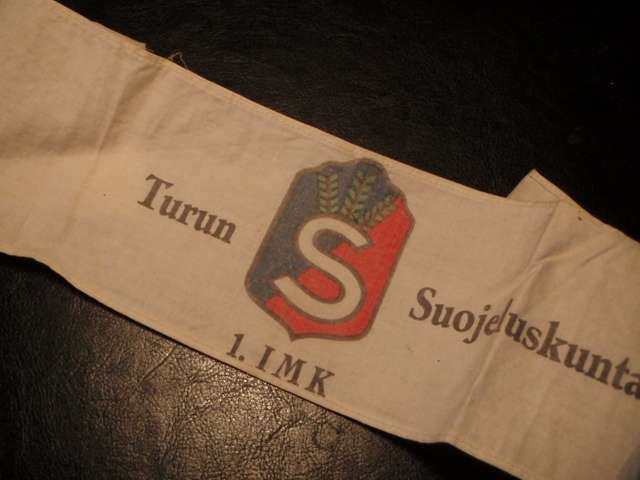

Cultural conflict and compromise

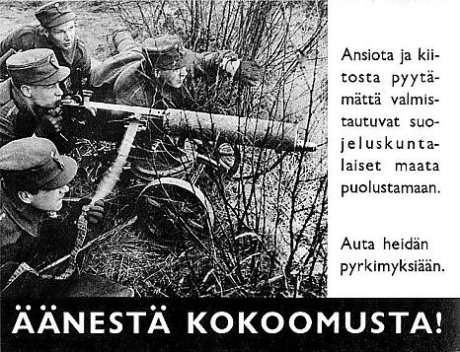

The scandal surrounding Fields and Barracks appears as the last great furore of the tensions surrounding conscripted soldiering in the early years of national independence. A gradual movement from an atmosphere marked by conflict towards political and cultural compromises can be discerned throughout the interwar period. In the political sphere, the politics of conscription slowly converged as first the Agrarians and then the Social Democrats gave up on the idea of a people’s militia and embraced the existing regular army, as the apparently most realistic protection against Bolshevik Russia and a safeguard of parliamentary democracy in the face of rising right-wing extremism. The professional military establishment met the Agrarians halfway by incorporating the Suojeluskuntas movement ever more firmly into the national armed forces.

A great deal of the officer corps obviously only realised very slowly how radically the conditions for the military training and the treatment of soldiers had changed after 1918, when universal male conscription was combined with national independence and parliamentary democracy. Incompetent NCOs were allowed to terrorise contingent after contingent of conscripts and severe hazing of younger soldiers was tolerated or even thought to serve the recruits’ adjustment to the military world. However, the material scarcity and shortage of officers and NCOs with adequate training that had plagued the army in the early 1920’s slowly eased. In the face of massive public criticism as well as the emergence of new ideas about military philosophy, the armed forces eventually seem to have responded and made some partial adjustments to how conscripts were trained and treated. As a result, the regular armed forces’ image in the public improved towards the end of the 1920’s and was mainly positive in the 1930’s. Conscription and military training became less controversial as the population became used to its existence and ever more men returned from their year in the army without having been noticeably corrupted.

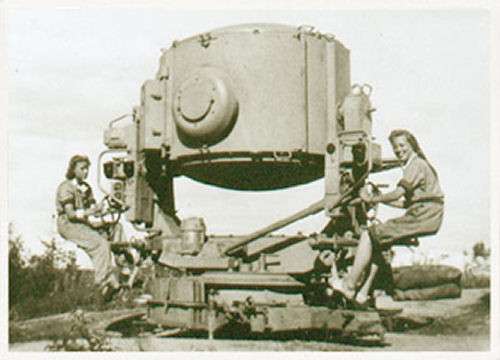

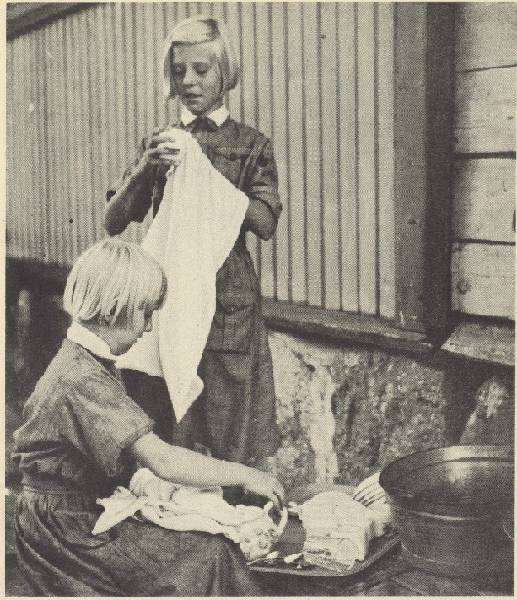

Over the 1930’s, the public image of the Finnish conscript army improved, as it became associated with the protection of positive national values among ever broader layers of society. Men’s (and in the last half of the 1930’s, many young women’s) experiences of military service became ever more positive and surviving its hardships and challenges became a matter of pride. Society was undeniably militarised to some degree as ever more men and women thought of military service as “a natural part of every citizen’s duties” and “a matter of honour for a Finnish man or women”. However, the political compromises and easing tension around conscription did not mean that Finnish men from all layers of society suddenly and wholeheartedly embraced the army’s civic education curriculum. At least within military training, the antagonisms between young conscripts and the disciplinary projects of both moralist educators and drillmasters continued, albeit in gradually less harsh forms. Writers in Suomen Sotilas continued to complain about the “false ideals of manliness” among the soldiers. Conscripted men continued to report on experiences of abusive treatment or excessive disciplinary harshness.

The interwar period was a period of contest between different notions of the military. Yet to judge by the materials studied, there was no clear winning party in that contest, no unambiguous persuasion to consent, no evident hegemonisation” taking place. The proponents of the cadre army system and the particular form of a self-disciplined military associated with it certainly benefited from the factor of institutionalisation; military training in the cadre army was a fact throughout the period and most conscripts had to undergo its practices, whether they wanted to or not. However, the comprehensive picture of developments in the 1930’s is one of incomplete convergence and persistent lines of division. Army stories display how both conscripts and officers often reproduced the social and political demarcation lines of civilian society within the military sphere. Many men certainly enjoyed the training and comradeship in the military, but few wanted or were able to verbalise friendship and intimacy in their reminiscences. Instead, their stories highlighted how group solidarity often meant either violently establishing outward boundaries towards civilians, other contingents or other units, or “comrade discipline” within the group in the form of ritualised group beatings. When the fact is added that the military treated conscripts differently depending on their educational background and political outlook – barring suspected socialists from officer’s training – one must question to what extent military training in practice really served the cause of a greater national unity.

There was a recurrent notion that the Finnish common man was a brave soldier, but jealous of his self-determination, reluctant to conform to hierarchies and suspicious of “lords and masters”. This unyieldingness was sometimes criticised, but actually more often idealised as evidence of a particularly Finnish manliness. This becomes apparent in images of the civil guardsmen in the Civil War, in the political rhetoric of the Agrarians, as well as in Pentti Haanpää’s and many other men’s army stories. Men who were too eager to comply with the military educational objectives were derided as “war crazy” by their comrades in military training. According to the army stories, exaggerated expressions of dutifulness and patriotism were shunned among the conscripts. Sociologist Knut Pipping described a similar mindset among the soldiers in his own machine gun company during the Second World War in his 1947 dissertation. Heroism or bravery was appreciated only to the extent that it served the wellbeing and survival of the group, not as an end in itself. Historian Ville Kivimäki has analysed Pipping’s account as displaying how the soldiers used their own standards for evaluating each other, including heavy drinking and womanising, certainly not the ideals of the “conservative” military. The most iconic Finnish post-war Finnish war novel, Väinö Linna’s The Unknown Soldier (1954), depicted Finnish soldiers in the same vein as Pipping, brave and tough fighters, scornful of ostentatious discipline and lofty patriotic rhetoric. However, Kivimäki points out that even if Finnish soldiers in the Second World War openly rejected many of the values of the military, their own values took for granted that a man had to, and would, fight and defend the nation.

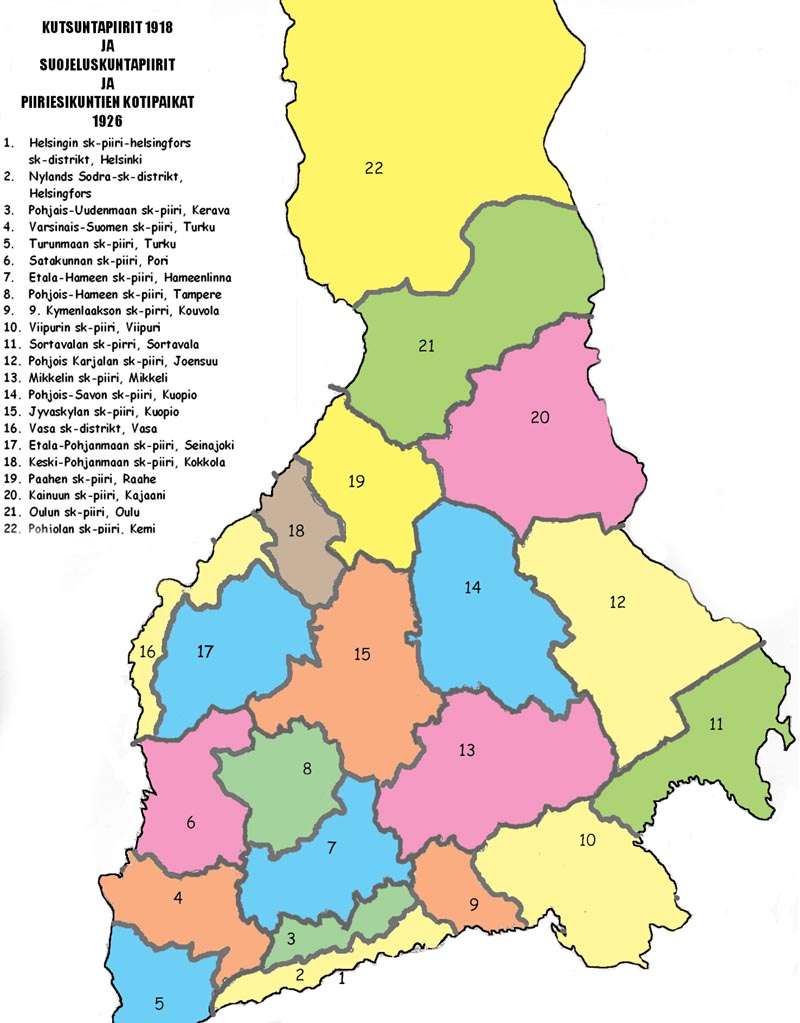

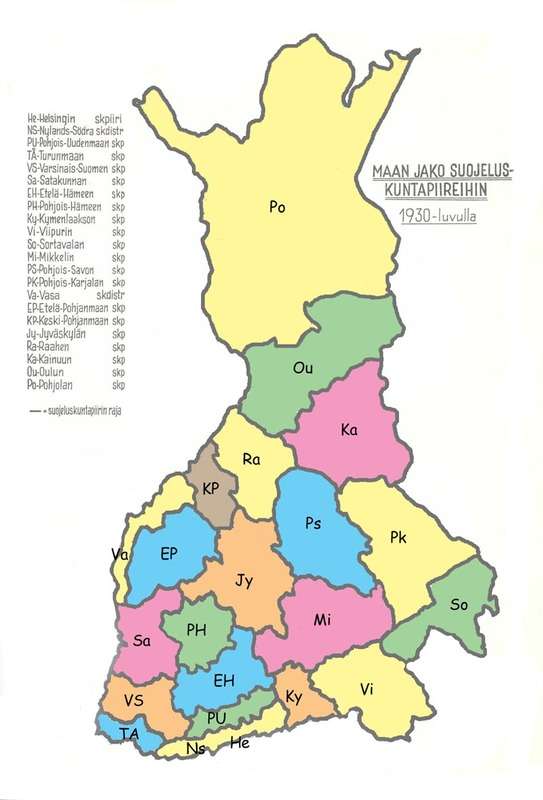

This concludes the Posts on Conscript Service in the 1920’s. Next will be a look at the Suojeluskuntas and Lotta Svard organisations in the 1920's, followed by a quick look at the origins and early years of the Suomen Ilmavoimat (Finnish Air Force).

Conscript soldiers and women

Up to this point we have studied Finnish conscript soldiers with reference only to military hierarchies and comradeships, the disciplinary methods and strategies of resistance or submission and their army experiences, with almost no reference made to women. This reflects how most men chose to recollect their military service. Their social relationships to women who were important in their lives at the time – mothers, sisters, female friends, girlfriends or wives – are largely left out of the narrative. However, this exclusion is not complete. In brief passages, even mere sentences or subordinate clauses, women are glimpsed now and again. In the 1972–1973 collection, some men mention in passing that they had a girlfriend or a wife either in their home district or in the garrison town. E.g. Kalle Leppälä (b.1913) had a girlfriend and even became engaged to her during his year in military training. He only mentions her existence as if by accident when accounting for the number of leaves of absence he obtained during his service. In his 357 pages of army memories, the longest story in the material examined by the author of this thesis, he writes nothing at all about what the forced separation from his partner felt like, how he coped with it or how they stayed in touch. Eero Tuominen, whose narrative is extraordinary in its emotional openness and articulateness, is an absolute exception, as he describes the longing for his girlfriend after reporting for service, the bliss of spending time with her on his one precious home leave, the anxiousness that she should find someone else while he was gone, and his sorrow and bitterness as her letters grew increasingly infrequent and their contact eventually flagged.

In Mika Waltari’s otherwise so open-hearted army book, the author only mentions the existence of his own girlfriend on page 91. According to Waltari’s autobiography, he met and fell in love with the woman who later became his wife one month before he reported for military service. In Where Men Are Made, however, he never tells the reader anything about her more than that she has blue eyes and a blue hat. It is not clear whether this was to guard his privacy or because he felt she did not really have a place in a book about his military service. Nevertheless, Waltari effectively omits the woman he chose to share his life with, although she evidently was an extremely important element in his life during his military training. He only hints at the happiness of four days on home leave having something to do with being in love, but he is rapturous in describing his return to camp after “a short sad goodbye” from his fiancée. It is ambiguous whether his happiness that night, back at camp, is due to being in love with his girlfriend or with the return to his groupd of soldier-comrades: “I undress in the dark, in the midst of sleeping boys breathing, the familiar smell of foot cloths and boots. Oh, everything, everything is beautiful.”

Seducers, beaux and innocents

An important part of the military culture reigning in interwar Finnish Army barracks seems to have been the repertoire of “naughty” marching songs. These songs ranged in content from raw pornographic and sometimes misogynist imagery to joyful celebration of the mutual pleasures for both man and woman of sexual intercourse. In all of them, however, a self-image of soldiers was cultivated – sometimes soldiers in general, sometimes the soldiers of one’s own unit in particular – as irresistible seducers of women, always on the move towards the next conquest. The soldier’s relationship to women in these songs, sung on heavy marches to cheer up the mood and copied in the soldiers’ autograph albums, was that of a classic Don Juan. This was also the image of soldiers’ relationships to women in popular Finnish films of the 1930’s. Advertisements for military farces alluded to the power of attraction military uniforms had for women. Using military metaphors for soldiers “conquering” women was usual in the screenplays. Recounting their own time as conscript soldiers, however, men gave a much more diverse picture of the conscripts’ force of attraction on women than in the wish-fulfilling fantasies of indecent songs. Some did not mention the soldiers having had any contact with women during their year of Service – apart from the “Sisters” at the service club, who were usually older than the soldiers, extremely highly respected and regarded as sexually out-of-bounds – whereas others mention that dating local women was common among the soldiers.

In these army memories, men do not brag about having been successful among women as they were soldiers. Some point out that it was hard to find female company in a large garrison town, with a considerable surplus of conscripts. An ordinary penniless infantry man had great difficulty competing with conscripts in the artillery, cavalry and navy who had fancier uniforms – not to mention the NCOs and officers with their well-fitted uniforms and golden insignia of rank. The class barriers in interwar society reoccur in some stories about how girls in finer clothes had to be “left to the officers” at a large ball at the theatre of Kuopio in 1929, or how ordinary soldiers from the countryside mainly dated country girls who worked as housemaids in the town houses of Oulu in 1925–1926. Many conscripts seem to have been rather sexually innocent at 21, as mention often is made of “experienced” or “more experienced” comrades, “womanisers”, who told their comrades wild stories about their sexual adventures or were observed with obvious fascination by their comrades. Contacts between soldiers and prostitutes are mentioned in a small number of stories – although none of the informants admit having paid for sex themselves – but they were evidently extensive enough to worry the military authorities, because of the spread of venereal disease. In this regard, the military system sent the conscripts a double message; the military priests demanded self-restraint and abstinence, lecturing the soldiers on the irresponsibility, filthiness and devastating effects on future marital happiness of contacts with prostitutes. The army medical service, however, took a more pragmatic approach, instructing conscripts who had sexual intercourse during leaves to visit the hospital when they returned for preventive treatment. Concealing venereal disease was punishable.

Mika Waltari, who was the most enthusiastic describer of warm and close comradeship among male soldiers in the author’s material, is also the only one to write at length about the significance of women within the military. His soldiers talk and dream about women when they are in camp and they eagerly date girls when they are back at their town barracks in Helsinki. However, women appear as distant and exotic in this world of men. To some they are creatures to be pursued, seduced and conquered, big game to brag to one’s friends about. Yet to Waltari and his close friends, who are middle-class and with a “good upbringing”, they are above all associated with a vision of the future, of marriage, of emotional satisfaction and security in a stable partnership. One night in camp, Waltari and his comrades lie around talking shyly about these things. “Of course we could talk and brag about the most incredible erotic adventures we have had, which are more or less fantasy. In fact most of us are very innocent, in the dangerous borderlands of manhood. Now that we are healthy and a new strength is growing in our limbs, we all feel distaste for brute erotic looseness. A dark night in some bushes or naked hostel room would be a heavy fall for us. Now that we have something to give, we want to keep ourselves pure – that same word that made such an irritating and banal impression in Christian morality lectures. Now we want to some day, when our true moment has come, give our whole strong youth. Get engaged and married when that time comes. In all of us glitters the beautiful illusory dream of a home of our own. Without our knowing, we are growing closer to society. Free, unfettered youth and the social system are always each other’s enemies. But here, through submitting, a deeper and greater solidarity has unconsciously been impressed upon us.”

In the depiction of this scene, Waltari reproduces an image, familiar from the storys by middle-class men writing in Suomen Sotilas, of conscripts as “pure” young men, living a stage of their lives centred on the community of conscripts, predestined although not yet ready for marrying and heading a household. This image was actually a vital precondition for the notion that the army was the place ‘where men were made’. If the recruits were already living in mature relationships, they would already have been real men and military training could not have been legitimised by claiming it brought them into this state of being. Waltari also makes an association here between submission, military service, becoming a loyal, responsible and useful male citizen, and getting married. Soldiering and fatherhood – in the sense of being responsible for a family of one’s own – thus join each other as two significant currents taking the young man towards adult, mature manhood and patriotic useful citizenship. The silence around marriage and serious partnerships in the other sources does not mean that they were not an important among the lower classes as well. In Pentti Haanpää’s army book, this is only hinted at through a few clues in his stories, yet in analysis it emerges as a key factor behind Haanpää’s criticism of military life. The Jäger sergeant major in his opening story not only goes home to take over his family’s little farm, as previously cited. He “fetches” a girl from the garrison town to live and form a family with her. She is not mentioned before the third to last sentence of the whole story although the Jäger evidently has had a lasting relationship with her. Haanpää lets the reader understand that the Jäger eventually finds a fulfilment that army life can never give him in a classic rural Finnish lifestyle based on marriage, fatherhood, land ownership and productive work. Twice he uses the word “barren” to describe the gritty military training fields, implicitly contrasting them to the proper place of a Finnish man, a field of corn or a timber forest where his labour bears fruit.

One explanation for the omission of girlfriends and wives in army stories and memories might be the habit of “undercommunicating” one’s marital status that ethnologist Ella Johansson has noted in the barracks and working camp culture of Swedish mobile workers in the early twentieth century. Being married and thus head of a family was strongly a part of the ideal for adult men. Yet this was played down among the workers, together with social and economic differences, in order to create a conflictfree atmosphere (one might say an illusion) of equality between men. This would seem to apply to both army barracks culture and the narrative tradition stemming from it. Sexual adventure with women was over-emphasised in army stories, whereas serious commitment with women was under-emphasised.

Finally, the silence of most men on what it was like being separated from one’s mother, sisters and possible female partners – sometimes for a whole year without a single home leave – should probably also be understood as informed by the narrative tradition of commemorating military service. This tradition was reflected and reproduced by the ethnologists organising the 1972–1973 collection. Among the more than two hundred questions they asked their informants, the only one touching upon the existence of women in the conscripts’ lives was a subquestion’s subquestion, under the topic of how evenings off-duty were spent in the barracks: “Was alcohol ever brought into the barracks? What about women?” The otherwise exhaustive questionnaire omitted any references to how the soldiers’ families related to their departure; if and how the conscripts stayed in touch with their families during the service; how they took care of possible problems arising at home due to their absence; or what home-coming was like. These subjects evidently did not belong to the story of a military experience shared by all conscripts. In a sense, leaving out women from the story of Finnish soldiering had a similar effect of strengthening the taken-for-granted notion that women and military matters had nothing to do with each other.

Conclusions: Class, Age and Power in Conscript Stories

Memories and stories about military training in the 1920’s show that popular images and notions varied and partly contradicted the pro-defence viewpoint. Many depictions of the disciplinary practices in use lie closer to the critique of the cadre army delivered by Social Democrats and Agrarians in the period, although men who recounted their own experiences of military training did not subscribe to the notions of its morally corruptive effects on conscripts. Class and age affected how men’s army experiences were formulated. Comparing Pentti Haanpää’s and Mika Waltari’s army books, the contemporary class divisions and politics of conscription serve as an explanatory pattern for the differences between them. From the vantage point of the 1970’s and old age, other men mixed the polarized interpretations of the interwar period into a kind of synthesis that did not serve the purpose of defending or criticising the cadre army, but of crafting a part of their own life-history.

Through his description of military comradeship, Mika Waltari conveyed an image of Finnish conscripts as boyish youngsters, blue-eyed boy scouts on the threshold of manhood and adult life. This was a prerequisite for the notion that military training could project them on a path to a higher level of being, to mature citizenship. That effect gave a positive meaning to the hardships they had to endure along that path. Through forming a community of comrades, a brotherhood-in-arms, Waltari’s citizen-soldiers supported and spurred on each other to learn and train for the task of men, defending the country. At the same time they were taught the self-control and unselfishness needed to submit. This experience, Waltari claimed, endowed conscripts with the self-confidence to face adult manhood with its responsibilities. The effect of Waltari’s narrative – whether it was his intention or not – was to defend the cadre army system by offering an attractive solution to the paradox between adulthood and submission, and claiming that it only changed men for the better.

Pentti Haanpää, on the contrary, suggested an image of Finnish conscripts who were no compliant young boys when they arrived for military service, but rough-hewn adult workmen. Military training had no personal value for them, and without a war to fight the hardships and humiliations involved appeared to them as meaningless sadism and oppression. Haanpää’s soldiers felt offended by military discipline and reacted by resistance and recalcitrance in any form available – shirking, cheating and lying. Haanpää had no use for the sedative notion of supportive comradeship that lessened the strain of life in a cadre army. In his portrayal, comradeship was more about an inflicted life together. He did not attempt to idealise military comradeship or even describe the conscripts’ ways of being men as particularly sympathetic. The message emerging from his stories was rather that this was what common Finnish men are like, like it or not, and if the cadre army system stood in contradiction to it, the military system had to change. To Haanpää’s workmen, the army was an oppressive interruption robbing them of autonomy and dignity, but to Waltari’s middle-class students it offered an opportunity to boost their white-collar self-image with the prestige of being not only warriors, but also the military leaders of their generation. Waltari wrote in the “white” tradition, describing an affinity between men in military service, united across all other differences by gender, nationality and soldiering. Haanpää’s images of soldiering were closely aligned with the political critique of the standing cadre army as an institution corrupting men, both through the oppressive violence of a detached officer caste and through the roughness of comradeship in the “unnatural” circumstances of men living isolated from society in an all-male military hierarchy.

These differences are interestingly congruent with those between the ‘modern’ middle class and traditional rural and working class views. Industrialisation and urbanisation, it has been argued in previous research, robbed the middle-class of its traditional stable foundations: landownership or autonomy as a self-employed artisan. In the emerging modernity, every middle-class man had to prove and demonstrate through “making himself” in the fierce competition of the marketplace. This notion of a need to demonstrate an ability that was not inherited as a social position from one’s father is strikingly similar to Mika Waltari’s eagerness to demonstrate that “he can make it where the others do”. Pentti Haanpää’s conscripts, on the other hand, navigate within a largely rural value system where great value is put on the autonomy based on controlling one’s own labour. The soldiers depicted by Haanpää try to claim a degree of self-determination by using strategies of obstinacy and wilfulness, similar to the contemporary culture in teams of male workmen, for example in forestry or railroad construction, as described by Ella Johansson.

The culture of shirking and malingering could also be conceptualized as Eigensinn, a term that Alf Lüdtke has used to describe how contemporary industry workers on the continent temporarily distanced themselves from the hierarchies and demands of the workplace, refusing co-operation and gaining some sensation of pleasure through teasing fellow workers, walking around, talking to people, taking unauthorized breaks or just daydreaming; anything one was not supposed to do during working hours. Eigensinn or wilfulness, as outlined by Lüdtke, is thus not a form of resistance against the system, but rather attempts by individuals to temporarily ignore or evade the system, to create moments and places of independence from and disregard of the surrounding social order, insisting on time and space of one’s own. Conscripts displaying Eigensinn thus did not necessarily want to challenge or change the military system. Rather, they needed some space to breath within it. In spite of the variations and differences across the 1972–1973 reminiscences, and the evident development towards better treatment of conscripts over the course of the interwar period, the collection as a whole reflects many experiences of military discipline, especially during recruit training, as containing elements of meaningless harassment reminiscent of Haanpää’s imagery. The explanations offered for superiors’ bullying, in terms of NCOs and officers taking out their personal frustrations and aggressions on their subordinates, are also in line with Haanpää. Yet none of the men who wrote about their military training after the Second World War really attacked the pre-war cadre army system in the same wholesale fashion as Haanpää. The cadre army had proven its worth in the war, and even if some men expressed bitterness over how they had been treated and wanted to expose the power abuses that had occurred, the general tenor in 1972–1973 was that interwar military training in its very hardness was necessary and useful.

Since it was not necessary any more to either attack or defend the institution itself, the stories written down in the 1970’s are actually less black-and-white than the interwar literary depictions. They needed neither the demonising story about an officer corps rotten throughout, nor the idealised myth of conscript soldiers’ unreserved solidarity and comradeship. Accounts of bullying and sadistic superiors could be accommodated in the same narrative with very appreciative descriptions of well-liked officers. Good comradeship and group spirit were mentioned in the same breath as violent conflicts among the conscripts were revealed. In the final analysis, many former soldiers evidently adopted the notion of military service as “a school for men”, a place where conscripts grow, harden and develop self-confidence through the very hardships they suffer, in order to invest a largely disagreeable or partially even degrading experience with a positive meaning. However, they did not idealise submission in itself nor the collectivist fusion with the group as Waltari did; theirs were individualist stories of their ability to cope.

Historian Thomas Rohkrämer has found the same pattern of a “growth narrative” surrounding nineteenth century German military service. The training, Rohkrämer claims, was intentionally laid out with an extremely hard and even humiliating recruit training in the beginning followed by slowly ameliorating circumstances. Once the soldier had adjusted to army discipline and taken on the behaviour his superiors wanted, he could enjoy certain rewards; a high social status in relation to civilians, an economically carefree existence, and a boosted attractiveness with women due to the “military bearing” and the gaudy uniforms of the epoch. Rohkrämer asks why so many men rallied round the cult of the military in the Kaiserreich and offers the explanation that military service was understood as an initiation that was accepted and celebrated afterwards. Once the hardships of military training had been endured they could reap the benefits from public notions of men with military education as characterised by energy, vigour and resolution.

From the early 1930’s on, a political consensus over the military system gradually emerged. As we have seen, the conscript army of independent Finland started out with severe image problems. Some of these were inherited from the standing armies of the authoritarian monarchies that served as organisational models for the Finnish cadre army. Other problems burdening the Finnish Army derived from the fact that it had been created in the midst of a civil war where its main task was to crush an internal socialist revolution. This initial ballast was further exacerbated through reports of the bad conditions that conscript soldiers were exposed to throughout much of the 1920’s. The pro-defence debate in interwar Finland must largely be understood against the background of widespread negative images of the existing military system. While pro-defence advocates made great efforts to disseminate positive images of military service, they had to compete with popular notions of the conscript army as a morally and physically unhealthy place for conscripts, as well as a culture of story-telling about personal experiences of military training that often highlighted the brutal treatment and outright bullying of conscripts.

Military service was described as strongly formative of conscripts’s physical and moral development, both by the critics and by the supporters of the existing military system. As the military system became a part of cultural normality, as the worst conditions were corrected, and as people grew accustomed to conscription and increasingly came to accept it – although not necessarily to like it – there was less need to talk about its impact. However, this was more the case in the political arena and the ideological propaganda of “civic education” than in the popular culture of telling stories about individual experiences of military training. Even if the notorious bullying of conscripts obviously diminished over the period, men still found personal use for the claim that going through a harsh and demanding training had made a positive difference to their personal life history.