Maavoimat Signals equipment through the 1920s and into the 1930s

Maavoimat Signals equipment through the 1920’s and into the 1930’s

As I mentioned a few Posts ago, please note that the content of this Post as far as OTL Finnish Army Radio and Signal’s equipment (and photos) is concerned is sourced from Antero Tanninen’s wonderfully detailed website, http://personal.inet.fi/koti/antero.tanninen/ - and more specifically, http://personal.inet.fi/koti/antero.tanninen/Radiotaulukko.htm - and is reused with Antero’s permission. If you’re interested in Finnish Radio equipment, Antero’s site goes into this subject in far greater detail than I’ve used – the content is primarily in Finnish but if you use Google Translate, you’ll get a pretty good idea of what it’s all about.

Suomen Maavoimat war-time field radios and field telephone / switchboard equipment at the time of the Winter War.

Note that this is not a complete listing of WW2 Maavoimat Radios, as the Maavoimat ended up with a wide range of equipment from many different sources – but it does give you an idea of the type of equipment that was in use as well as its capabilities.

In general terms, there were four types of Field Radios that were in common use by the Maavoimat. These were the:

AB-Radio: Used by the higher echelons of the Maavoimat (Army Bases, Headquarters, etc) for communications over very long distances;

B-Radio: Used at Corps, Division and Regimental Headquarters for commmunications between Headquarters units;

C-Radio: Radio communications within the Infantry Regiment and at Battalion HQ Level for the Battalions and major supporting units that make up a Regiment

D-Radio: Infantry Company, Artillery Fire Control, Close Air Support and smaller units within the Regiment.

Below, as well as examples of Field Telephones, we will list examples of each type of Field Radio together with capabilities (and photos).

Field Telephone and Field Telephone Switchboard Equipment

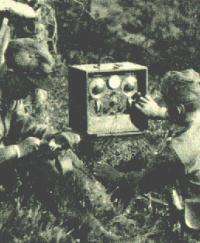

Signals Battalion soldier at work. Field Telephone Switchboard. Suomen Maavoimat, 1920’s

Signals Battalion soldier at work. Field Telephone Switchboard. Suomen Maavoimat, 1920’s

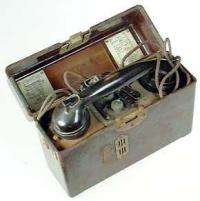

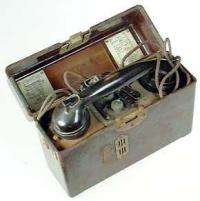

Two early-model Field Telephones used by the Maavoimat: The top phone is a Siemens & Halsken produced field telephone model "Grosser Feldfernsprecher" made in 1917. The phone in the lower image is also a Siemens & Halsken – a "Feldfernsprecher" model from 1916. These remained in service with the Maavoimat until 1939, after which they were replaced by the new models. However, with the Winter War, they remained in stock as war reserve material and were used to replace combat losses.

Virolaisen kenttäpuhelimen vanhempi malli 1920 vuoden loppupuolelta. Valmistaja Tartu Telefoni Vabrik. / Field Telephone manufactured for the Maavoimat by Tartu Telefonika of Estonia (at this stage not yet owned by Nokia) – an older P-1-8 1920 model.

Field phones boxes were originally made of hardwood such as oak. Wood as a construction material was however relatively expensive and ill-suited to mass production. Thus, in the 1930’s, resin’s quickly replaced wood as the material of choice for casings. Bakelite was perfectly suited to mass production because the cases could be made using die-casting molds. This Field Telephone was one for the early models constructed with a bakelite casing. The cases were also more robust, lighter and more waterproof than the older wood cases.

Suomen armeijan toisessa maailmansodassa käytössä ollut Helvarin sotilasradio. Luultavasti P-12-12u "Kukkopilli" malli. Kuvattu Hangon rintamamuseossa / Helvar military radio-telephone used by Finnish army in World War 2. Likely a P-12-12u "Kukkopilli" model. Photographed in Hanko front museum.

The Early Days of Radio in the Maavoimat

But first, an explanation of the Finnish four or five digit device code that you will see associated with almost all Radios:

V = communications (/ signals) device

R = radio (wireless)

G = D station / radio for artillery fire control and infantry company

K = producer (and/or country of origin): ASA

[none], A, B, C... = version

Radioasema toiminnassa metsässä 1928 / A radio station operating in the woods – 1928. The figure shows a wintry forest, and two men on skis, one standing, one leaning over the sled. The leaning man is recording a message. Both men are soldiers,

As mentioned above, there were four types of Field Radios that were in common use by the Maavoimat. These were the:

AB-Radio: Used by the higher echelons of the Maavoimat (Army Bases, Headquarters, etc) for communications over very long distances;

B-Radio: Used at Corps, Division and Regimental Headquarters for commmunications between Headquarters units;

C-Radio: Radio communications within the Infantry Regiment and at Battalion HQ Level for the Battalions and major supporting units that make up a Regiment

D-Radio: Infantry Company, Artillery Fire Control, Close Air Support and smaller units within the Regiment.

The use of radio as a field artillery fire control device began to develop rapidly within the Maavoimat from about 1925. Prior to this, in 1923 General Vilho Petter Nenonen, a versatile and brilliant artillery commander of whom we will see much more, had sought to gain experience in the use of radio as an arillery fire control tool. As far as is known, at this stage no other country had carried out such experiments with the use of suitable and lightweight radio equipment for this task. Nenonen’s first experiments were carried out using heavy horse and cart-based radios. As a result of the experiments, Nenonen ordered two radio stations as a trial and these were completed in 1924. The two-man portable radios were designed to have a voice range of about 10km but on completion, it was found that the range was as much as 50-60km. The experiment resulted in further action, and on 26 May 1924 the Artillery Inspector ordered the Artillery Regiment to select from among its members one officer and one NCO for training with the Signals Branch.

In Order No 403/27.6.24, Nenonen explained to the Army C-in-C the reasons why he considered it important that the artillery should use light-weight, portable radio equipment. The statement also explained the technical requirements of stations, and suggested that each Artillery Battalion should be allocated 2 radio stations to communicate with higher headquarters, regiments and forward artillery observation and control stations. In addition Nenonen in 1925 gave the technical a written order that a Radio Battalion was to be created for experimental training purposes, and 10 portable radio stations were to be built in accordance with the already-advised specifications.

Radio stations made by the Radio Battalion, however, were still quite bulky and difficult to use. Continued work on improvements to reduce the weight and improve ease of use was carried out but it proved more or less impossible for the Radio Battalion to reduce the weight to less than 13kg. In June 1925, Nenonen presented the Radio Battalion woth a simple wiring diagram which was based on amateur radio circuit designs. Slowly, due to the bureaucracy that then reigned, the Radio Battalion built Nenonen two stations. These smaller and lighter“Perkjärvellä” radios were tested and they worked very satisfactorily for the Artillery. The new Artillery portable radio stations began to be used for LTJ-radioiksi (mobile artillery fire control). Thus, thanks to Nenonen’s foresight and the measures he took, by 1927 Finnish Field Artillery was already using portable Radios as well as wire-based communications in all peace-time exercises. In this, the Maavoimat was significantly ahead of all other militaries – and it was a lead that would continue to grow through the 1930’s, as we will see.

The A-Radio and AB-Radio

The VRBIA was large, usually permanently installed and was used by the highest formations and levels of leadership (Military HQ, Corps HQ, large Air Bases). It was also used for air and sea forces and later, by the Border Guard Department. The device operated in both short and long-wave, or both depending on the configuration. It could send both voice and telegraphy and Transmit power was hundreds of watts. The transmitter shown was usedthrough to the beginning of the 1970s.

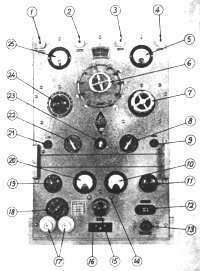

An AB radio transmitter-receiver: This was a large Field Radio, usually transported in a Car or Trailer and operated inside a building, tent or bunker. Range was approximately 500km for Morse and about 100km for Voice. Power was provided by a Generatorwhich kept the batteries charged and three different length rubber-coated antennae were used – 8, 20 and 25 metres (the length of the antenna to be used was determined by the frequency on which the radio was to operate). The radio equipment and tools were packed in a total of four cases for transport. The full equipment weight was 462 kg.

The B-Radio

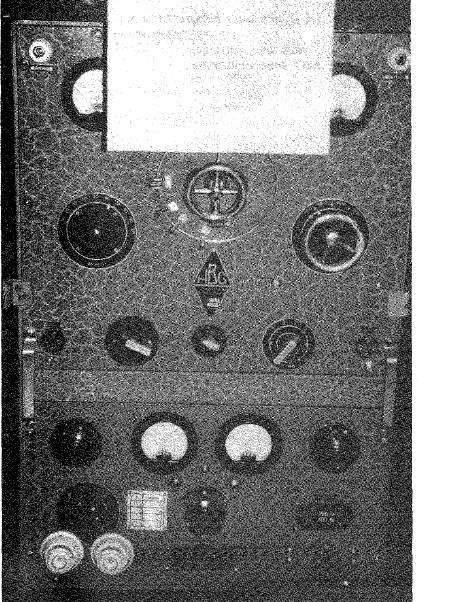

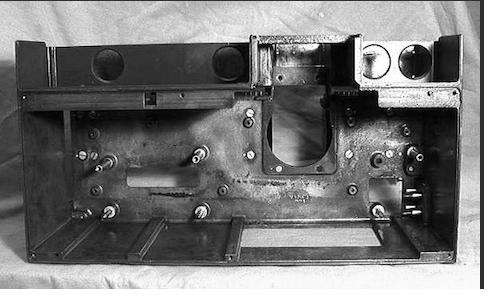

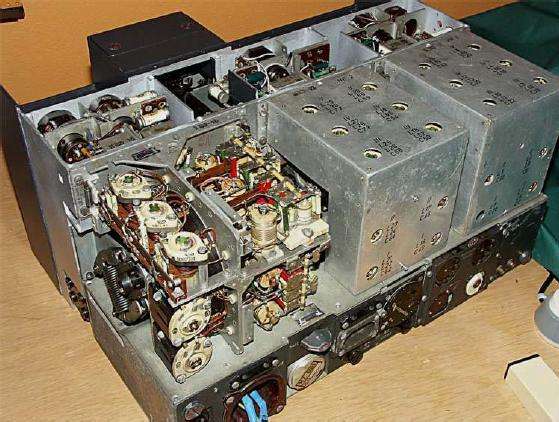

This P-12-5 B-Radio was in fact the same as a C-Radio, but built to a higher current rating. The transmitter and the receiver were in the same box.

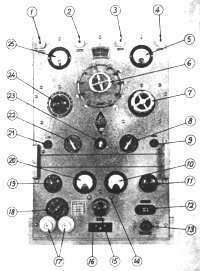

Below, a Helvar P-12-6 (RL20) VREH “Bertaa” B-Radio

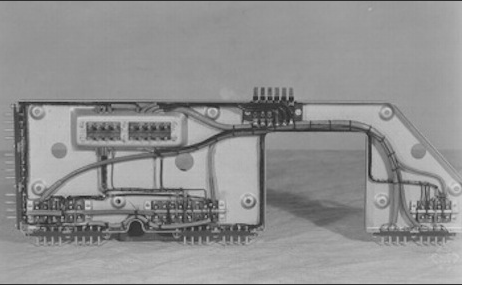

A HELVAR B station, P-12-6, VREH (B) Two-channel transmitter and receiver. The Transmit power was 20 W CW and voice-6 W. Morse range was about 200-300 km, about 60 km for speech. The Radio is a medium-duty vehicle transported, two-channel field \radio, which was carried in five shipping cases: a transmitter-receiver box, the machine converter box, 2 boxes for the batteries and battery charger and the generator which powered the battery charger. The Equipment weighed a total of 185 kg without the battery charger. The radio was equipped with two rubber-coated antenna with a length, of 20 and 10 m and a 3-arm 3 x 8m long rubber-coated counterweight. The antenna length was chosen dependent on the working frequency selected.

The C-Radio and the C-D Radio

C-Radio: Powered by a 4.5 V battery, this was both a Voice and Morse Transmitter-Receiver.

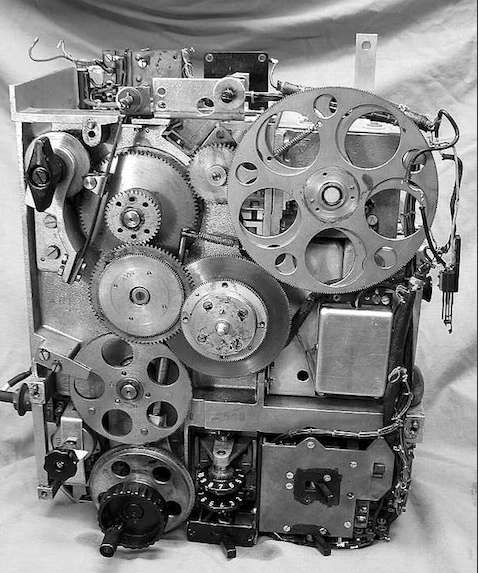

C-D Radio: This was a portable two-channel field radio. The transmitter and receiver are in different boxes. The power supply and accessories are housed in four cases in total. Range was 30 km for morse and 15 km for speech. The equipment weighed 65 kg in total and was powred from batteries charged from a small generator.

The D-Radio

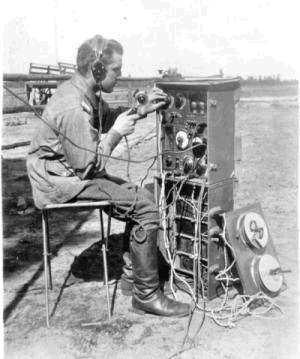

D-Radio station. The photo was taken at Santahamina on 21 October 1932. The Radio belonged to 1/Kenttätykistörykmentti 3

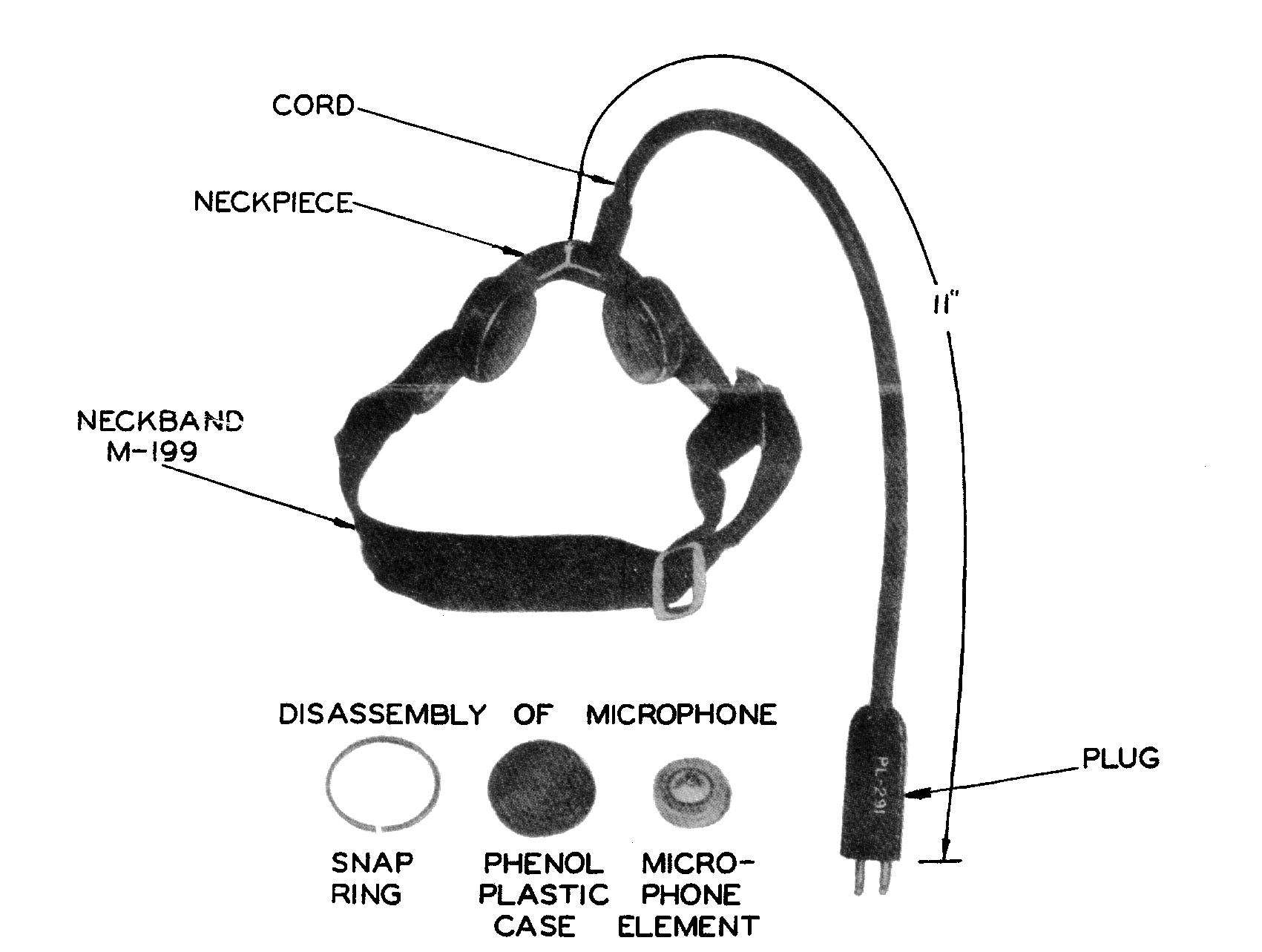

The D and C radio receivers were similar, but the D-station transmitter, however, was completely different from the C- radio. (Image above is the receiver.) The antenna was made of metal tubing and was a collapsible loop antenna, which is attached to the box sides. The antenna is shown in the upper image (slightly). Power source was a 4.5 V light battery, which was placed in a separate battery box. The transmitter could be used for speech, as well as for morse. The angle of the Ring antenna was manually adjusted to achieve optimum reception.

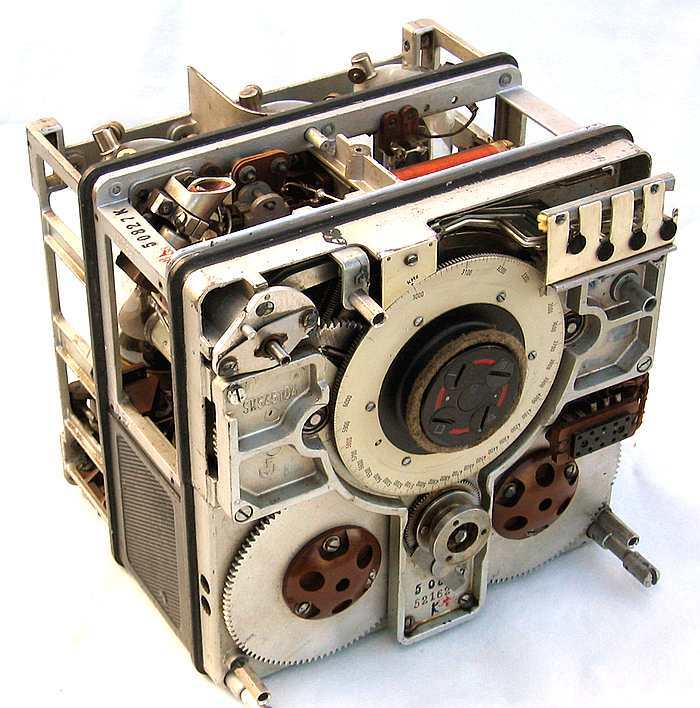

Suomalainen P-12-15 VRGK sotilasradio. D-luokan eli tykistön tulenjohtoradio, valmistanut ASA vuonna 1941. Antenniteho 0,4 W, taajuusalue 4,6-6,6 MHz, yhteysväli sähkötyksessä 20 km, puheyhteydessä 12 km. Kuvattu Hämeenlinnan tykistömuseossa / Finnish P-12-15 VRGK military radio. Artillery fire control (class D) radio, manufactured by ASA in 1941. Transmission power 0.4 W, frequency 4.6-6.6 MHz, wireless telegraph range 20 km, radiotelephony range 12 km. Photographed in Hämeenlinna artillery museum.

Suomalaiset VRLK (oikealla) radiovastaanotin ja VRGK sotilasradio, molemmat Asa radion valmistamia. Kuvattu Jalkaväkimuseossa / Finnish VRLK (right) radio receiver and VRGK military radio, both manufactured by ASA Radio. Photographed in Mikkeli Infantry museum.

Tornister Funkgert d2 Military Radio: The Finnish marking is VRKS, it is probably a mortar team radio, of German origin.

This is a Finnish made P-12-15 (or VRGK) portable single channel field radio (sender - receiver) produced by ASA Oy. It was classed as a "D radio" which meant it was mainly used by forward artillery observers and by infantry companies. The D-Radio could be used in telegraph (A1) and voice (A3) modes, and could be used with a separate telephone. The total weight was about 30kg, packed in two plywood boxes (one for the radio, one for the batteries). The antennae was a 10m long rubber-coated “throwable” aerial. A number of different versions were built, incorporating a number of improvements with each. The price per unit was approx. 15,000 Markka – they weren’t cheap, but despite this they equipped around half the Finnish infantry units in the Winter War, together with a large number of supporting units, air surveillance posts and the like, with some 1,800 in service in late 1939 (with a total cost of some 27,000,000 markka, this was not an insignificant cost)

The Signals Branch of the War Department – a brief history

The War Department’s Radio Telegraph Branch had been founded in the summer of 1918. It was based at the military headquarters in Mikkeli and initially consisted of the Radio School, and later included the Heavy Field Radio Division which had been formed during the civil war from radio men and willing volunteers. The Light Field Radio Department in Helsinki (based at Santahamina) later also joined the Branch. The Heavy Field Radio Department was based first at the University of Helsinki Department of Physics, but in the autumn of 1918 it was transferred to Santahamina. Conscripts began training om Signals from August 1918. The Heavy Field Radio Department’s radio station was responsible for radio communications over the whole of Finland to naval and merchant ships as well to the state-owned icebreakers.

The Branch also began to teach civilians radio and telegraph skills. In 1920, a Radio Workshop was established and both military and civilian radio communications were carried out. Signals Branch strength from 1922-1925 was between 180-250 conscripts, of whom 85% studied and completed Signals courses successfully. From 1923, the armed forces Divisional radio sets were assembled at Santahamina and in 1924 the Radio units of the Signals Branch were grouped into the newly formed Radio Battalion. At that time, the Post and Telegraph Office was taken over by civilian broadcasting, as were the the fixed point radio stations, with the Santahamina being the last position handed over in May 1925. After the transfer of the civilian radio stations, the Radiopataljoonassa (Radio Battalion) had two radiokomppaniaa, as well as both a depot and a repair workshop. By 1926, the Radiopataljoonassa strength was about 20 officers, 40 NCO’s and approximately 200-250 conscripts.

Organizing the Signals Branch:

In the early 1930’s, the Signals Branch began to be substantially reorganized as part of the overall restructuring and reorganization of the Maavoimat as a whole. Up until 1933, the Signals Branch had been combined as part of an overall scientific-technological forces grouping which consisted of the Engineers, Transport and Armoured forces as wekk as Signals. But in 1933, the Signals Branch was finally made an independent Branch of the Armed Forces and in 1934 the Signals Regiment was established, based from Viipuri, where the Signals School was also constructed. At the same time, the Signals units within the Maavoimat were reorganized at the Divisional, Regimental and Battalion level with the end result outlined below.

The Maavoimat’s combat formation signals units….

On the outbreak of the Winter War in late 1939, the Suomen Maavoimat military communications structure within a standard Division was largely organized as set out below. Keep in mind that in 1939, following a decade of organizational restructuring to optimize combat capabilities, the standard Maavoimat combat formation was a Regimental Battle Group, three of which were organized into a Division for logistical support and command oversight purposes. As such, the composition of a Regimental Battle Group was in practice intended to be flexible and suited to the assigned mission objectives: for the purposes of this post, a standard formation will be assumed (Maavoimat Unit Organisation will be covered in a separate Post or Posts).

As such, a Regimental Battle Group was intended to be a self-sufficient fighting force with all necessary supporting units integrated into its structure. Thus, many supporting formations that in other Armies were commanded at a Divisional level were, in the Maavoimat, built into the Regiment. With Signals, where other Armies had a Signals Battalion at the Divisional Level, the Maavoimat had an overstrength Signals Company at the Regimental level. Maavoimat signals structure is laid out below.

Division (Divisoona): At Divisional level, there was a Divisional Signals Commander, typically a Captain, in charge of a Divisional Signals Company (Viestikomppania, VK) and a Line Contruction Company (Linjanrakennuskomppania, LRak.K) which were intended to meet all Divisional-level signals requirements. Divisional Signals units were responsible for establishing and maintaining links to Regimental Battle Groups and to all independent units attached to the Division as well as for the establishment and maintenance of lines and radio communications to Army Corps Headquarters as well as to Divisional observation and forward artillery control aircraft (while these were Ilmavoimat aircraft, they were attached to, and under the operational command of, Maavoimat Divisional HQ’s).

Divisional Signals Company (Viestikomppania, VK)

Company Commander – Officer, usually a Captain who, when needed, could be used as a substitute for the Divisional Signal Commander

Telephone Switchboard Platoon (Keskusjoukkue)

2 Telephone Switchboard Squads

1 Field Telegraph Squad

Radio Platoon (Radiojoukkue)

6 x C-asema (C Station) (0+1+3 = 4) [4 person team per C Radio]

1 x Ilmaviestiryhmä (specialised Radio Squad for communicating with Divisional Observation and Forward Artillery Control Aircraft)

Messenger Platoon (Lähettijoukkue)

3 x Messenger Squads (Motorcycle, Bicycle or Horse messengers)

Signal Equipment Repair Shop (Viestivälinekorjaamo)

Supplies Platoon (Toimitusjoukkue)

Divisional Line Contructing Company (Linjanrakennuskomppania, LRak.K)

Company Commander – Officer, usually a Lieutenant

3 x Telephone Line Platoons (Puhelinjoukkue)

each Platoon, 3 x TelephoneSquads (responsible for laying and fixing cables)

Supplies Platoon (Toimitusjoukkue)

Regimental Battle Group: All Signals units and detachments within the Regimental Battle Group were the responsibility of a Viestikomentaja (Signals Commander), although in practice the Signals Detachments formed part of the unit they were attached too and were under the direct command of the unit commanding officer. By mid-1939, with the growth of the Signals Network, each Regimental Battle Group contained a Regimental Signals Company (Viestikomppania, VK) which was also responsible for Field Telephone Lines where these were used. In addition to Regimental signals companies there were smaller Signals Detachments (Viestielin) in attached Artillery Batteries and also with other specialized units directly under the control of Regimental HQ (examples being the Heavy Mortar, Anti-Tank and Pioneeri companies);

In Artillery Batteries and Heavy Mortar Companies, the Signals Detachments (Viestielin) were primarily responsible for the connections with Regimental and Battalion HQ’s and with the Fire Observing Squads (Tulenjohtue) attached to each Infantry Company. Signals Detachments (Viestielin) strength at the Artillery Battery / Mortar Company level was generally 8 men – 2 NCO’s and 6 Privates. The Fire Observing Squads (Tulenjohtue) were made up of 3 men – 1 NCO and 2 Privates.

Regimental Battle Group Signals Company (Viestikomppania, VK)

Company Commander – Officer, sometimes a Captain but often a Lieutenant

Telephone Platoon (Keskusjoukkue)

1 x Telephone Switchboard Squad

2 x Telephone Squads (responsible for laying and fixing cables)

Radio Platoon (Radiojoukkue)

6 x C-asema (C Station) (0+1+3 = 4) [4 person team per C Radio]

1 x Ilmaviestiryhmä (specialised Radio Squad for communicating with Divisional Observation Aircraft and Close Air Support aircraft)

Messenger Platoon (Lähettijoukkue)

3 x Messenger Squads (Motorcycle, Bicycle or Horse messengers)

Signal Equipment Repair Shop (Viestivälinekorjaamo)

Supplies Platoon (Toimitusjoukkue)

Battalion (Pataljoona): Each Battalion contained a Signals Platoon (Viestijoukkue, VJ) which was responsible for establishing radio connections and field telephone connections down to the individual Companies (and at times to Platoons) and to attached units such as the Battalion Anti-Tank Gun Platoon, Mortar Platoon and the AA Gun Platoon. Total strength of the Signals Platoon was 1 Officer + 10 NCOs + 36 men = 47 men in total. The Signals Platoon was theoretically organized as follows:

Joukkueenjohtaja (Platoon Leader - Officer)

Joukkueenvarajohtaja (Deputy Platoon Leader - NCO)

Radio Personnel: (total 0+4+12 = 16)

3 x C-asema (C Station) (0+1+3 = 4) [4 person team per C Radio]

1 x Ilmaviestiryhmä (0+1+3 = 4) (specialised Radio Squad for communicating with Divisional Observation Aircraft and Close Air Support aircraft)

Telephone personnel: (total 0+3+18 = 21)

Asemaryhmä (Station Squad) (0+1+3 = 4)

2 x Linjarakennusryhmä (Line Constucting Squad) (0+1+7 = 8)

Hevosajoneuvot (horse vehicles) (0+1+7 = 8) [6x telephone vehicles, 2x radio vehicles]

Infantry Company: There was no specific Signals Unit in an Infantry Company. Instead, the Company Command Squad (Komentoryhmä) included a 3 man Signals Team (1 NCO, 2 Privates) with a single “D” Radio. There was also a 4-Man Security and Combat Messenger Detachment made up of an NCO Combat Messenger [Aliupseeritaistelulähetti] and three Combat Messengers [Taistelulähetti] who doubled as a Company level Linjarakennusryhmä (Line Constucting Squad) responsible for running Field Telephone Lines down to the individual Infantry Platoons within the Company. In addition there were also two Combat Messengers [Taistelulähetti] for contact between company and battalion in the event that both Radios and Telephone Lines were down. Generally, there was also a Fire Observing Squad (Tulenjohtue) made up of an NCO Observer [Aliupseeritähystäjä] and two Observers [Tähystäjä] attached to each Infantry Company Command Squad (Komentoryhmä) and also equipped with a “D” Radio. Where the situation was static, there was generally a single Field Telephone with each Platoon Command Team. This was the situation at the start of the Winter War, but as the new, more compact one-man Nokia Backpack Combat Radios began to be available in mid-1940, these were issued first at the Platoon Level, with one of the new Radios per Platoon.

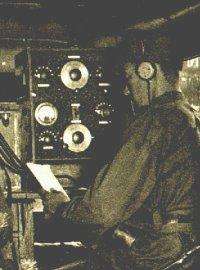

Maavoimat Lotta Svard Signals personnel operating a “B-Radio” – Summer 1940: Lotta Svard volunteers made up some 80% of rear-area Signals Personnel – With some 16,000 rear-area signals personnel, the Lotta Svard volunteers made a substantial contribution to the Maavoimat’s combat strength, freeing up enough men to form an additional 3 Regimental Battle Groups (more or less one additional Division). These Lotta’s were likely part of a Regimental Battle Group Headquarters Signals Company (Viestikomppania), although Lotta’s filled slots as far down as Battalion Signals Units.

Rear-area Signals Lotta, probably a Divisional or Corps Headquarters Signals Unit

Viestintälotat (Signals Lotta’s): Summer 1940, near the frontline. From the radio, probably part of a Battalion (Pataljoona) Signals Platoon.

And I just had to throw this in: “Mummosoti”(“War-Granny”) – don’t mess with a Finnish Grandma who used to be a front-line Viestintälotat in the Winter War – and who kept her trusty assault rifle hanging around afterward in case those pesky Russki’s decided to give it another go……. and be on your best behavior when you arrive for dinner with her granddaughter……

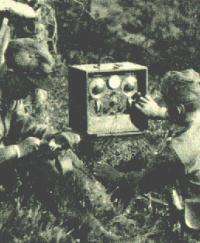

A signals repairman has started repairing a D-radio in the field. Photographed Summer-1940 on the Syvari, in the sector of Regimental Battle Group 56

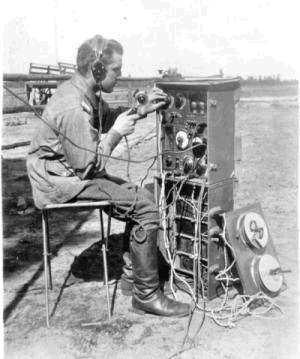

The D-radio in action during the Winter War: The photograph is from an artillery observation post. Finnish Artillery units trained their own Signals personnel for Signals duties. There were usually 2 “D” Radios per Company at a minimum – one for communications to Battalion HQ and one for Artillery Fire Control. Where Platoons were equipped with Radios (unsual in 1939), there were at times up to 5 Radios per Company, although this was the exception and not the Rule, given that a Radio Team consisted of 3 men.

The Finnish Radio Industry Moves to a War Footing – December 1938

As has been mentioned, following the Munich Crisis of late 1938 the Government approved substantial increases in Defence Spending as well as emergency financial appropriations. Much of this funding was directed towards weapons but there was also a sizable amount budgeted for communications equipment and some directed to R&D work, with interesting results. The funds made available were largely directed towards rush orders for the production of Field Telephone and Radio Equipment that was already in service but which was required in greater numbers to ensure units were equipped up to their ToE. Initially these orders were met by a partial reduction in production for the civilian market and the addition of an extra Shift by the manufacturers in order to meet the military orders. However, with the threat of war far higher in the summer of 1939, all radio manufacturing facilities were shifted to full war production, resulting in the almost complete curtailment of production for the civilian market.

With Finnish radio manufacturers already producing radios for the military, the switch to full war production was rapid. Civilian radio manufacturing ceased, equipment specific to civilian radio production was placed in storage and output for the military doubled almost overnight. Military Radio’s were not cheap items – a standard “D” type radio for example cost in the region of 15,000 Markka. But the end result was that by the late Autumn of 1939, all military units were equipped up to the TOE with radio and field telephone equipment and supplies and a substantial war reserve had been built up. This was fortuitous as it turned out – it meant that after the fighting started, combat losses could be quickly replaced and as foreign volunteer units began to arrive, they could be equipped with standard Finnish military communications equipment.

On the eve of World War 2, all nations employed generally similar methods for military signaling. The messenger systems included foot, horse-mounted, motorcycle, automobile, airplane, homing pigeon, and the messenger dog. Visual agencies included flags, lights, panels for signaling airplanes and pyrotechnics. The electrical agencies embraced wire systems providing telephone and telegraph service, including the printing telegraph. Both radiotelephony and radiotelegraphy were in wide use, but radiotelephony for tactical military communication was still in its infancy in most countries – Finland being rather further along than most. The navies of the world entered World War 2 with highly developed radio communication systems, both telegraph and telephone, and with development under way of many electronic navigational aids. Blinker-light signaling was still widely used. The use of telephone systems and loud-speaker voice amplifiers on naval vessels had also come into common use. Air forces employed wire and radio communication to link up their bases and landing fields and had developed airborne long-range, medium-range, and short-range radio equipment for air-to-ground and air-to-air communication.

In communications electronics, World War II was in one sense similar to World War I: the most extravagant prewar estimates of military requirements soon proved to represent only a fraction of the actual demand. The need for all kinds of communication equipment and for improved quality and quantity of communications pyramided beyond the immediate capabilities of industry. An increase in manufacturing plant became vital, and research and development in the communications–electronics field was unprecedented.

The German blitzkrieg of 1940, with its highly visible use of armoured formations operating in conjunction with close air support, emphasized a new order of importance for reliable radio communication. The early development (mid-1930’s) within the Maavoimat of the combined arms infantry, artillery, and armoured team with close air support had created new requirements for split-second communication by radio among all members. Portable radio sets were provided as far down in the military echelons as the company (and by mid-1940, the Platoon). At the start of the Winter War, every Maavoimat tank was equipped with at least one radio and in some command tanks as many as three. Multiconductor cables provided wire communications; they could be reeled out rapidly and as many as four conversations could take place on them simultaneously through the use of carrier telephony. The Finns were, after the Germans, the first to use this type of military long-range cable. High-powered mobile radio sets were pervasive within the Maavoimat at Division, Regimental Battle Group and even at Battalion level where the Battalion operated independantly. With these sets telegraph communication could be conducted at distances of more than 100 miles (160 kilometres) with vehicles in normal motion on the road. Major telephone switchboards of much greater capacity were needed and by late 1939 these were developed, manufactured, and issued for use at all Maavoimat tactical headquarters to satisfy the need for the greatly increased number of telephone channels required to coordinate the movements of field units whose mobility had been expanded many times.

Radio relay, born of the necessity for mobility, became the outstanding communication development of World War II. Sets employing frequency modulation and carrier techniques were developed by Nokia post Winter-War and used, as were also radio relay sets that used radar pulse transmission and reception techniques and multiplex time-division methods for obtaining many voice channels from one radio carrier. Nokia designed and developed radio relay, telephone and teletypewriter circuits spanned the Gulf of Finland after the invasion of Estonia (E-Day) in late April 1944 and later furnished critically important communication services for Kenraaliluutnantti (Lt-Gen) Karl Lennart Oesch, after his breakout from the Estonia beachhead.

Commander of the E-Day Invasion, Kenraaliluutnantti Karl Lennart Oesch (on the left) monitors the situation in the Estonian beachhead, early May 1944. The commander of the Maavoimat’s Estonian 31st Field Infantry Division, Lt-Gen Nikolai Reek stands second from the right.

Nikolai Reek (Estonian Cross of Liberty, Latvian Order of Lāčplēsis, Polish Order of the White Eagle, Lithuanian Grand Cross of the Order of Vytautas the Great, Mannerheim Cross, 2nd Class (posthumous)): born Nikolai Bazõkov; February 1, 1890 Tallinn, Estonia – April 8, 1945 Germany) was commander of the Maavoimat’s Estonian 31st Field Infantry Division in the E-Day landings of late April 1944 along the Estonian coastline which took the Germany Army (and the Red Army for that matter) by surprise. An Estonian military commander during the Estonian War of Independence, Reek graduated from the Tasarist Russian Chuguyev Military Academy in 1910. He fought in World War I, and in 1917 graduated from the Imperial Nicholas Military Academy. Reek joined Estonian units in 1917 and was Estonian Army Chief of Staff until dissolution of these units. After that he organized the Estonian Defence League in Virumaa. In the Estonian Liberation War Reek was firstly commander of the 5th regiment on the Viru Front and then in January 1919 he became Chief of Staff of the 1st Division. In April he became Chief of Staff of the 3rd Division. Reek played an important role in winning the war against the Baltische Landeswehr. In September 1919 he was promoted to Colonel and served as Chief of Staff on the Viru Front. After the war Reek repeatedly served in positions of Estonian Army Chief of Staff, Minister of Defence and Commander of the 2nd Division. In 1938 Reek was promoted to Lieutenant General.

In September 1939, when Estonia reluctantly agreed to allow 25,000 Red Army troops to be based on Estonian soil, Reek was once again Commander of the Estonian Army’s 2nd Divison. With the Estonian Army’s 5 Infantry Divisions (mostly Reservists) fully mobilized over late 1939 and into early 1940 and in complete sympathy with Finland as the Winter War was fought, Stalin had ordered the seizing of Estonia in the Summer of 1940 despite, or perhaps because of, the hammering that the Red Army was taking from the Maavoimat. The Red Army assembled 160,000 men, supported by 600 tanks and 1,150 aircraft. The Soviet NKVD was ordered to be ready for the reception of 100,000 Estonian prisoners of war. On 13 June 1940, Soviet forces began to move.

The Soviets had seemingly learnt nothing from the debacle of their attack on Finland. The entire tale is for another day, suffice it to say that Reek led the Estonian Army’s 2nd Division in the defense of the western sector of the Latvian Front, fighting a withdrawal battle that has gone done in history as a classic example of a successful fighting retreat against overwhelming odds. With the Narva Line holding the eastern flank of Estonia’s defences almost to the end, the Estonian forces over the month of July 1940 slowly fell back on the Tallinn Redoubt, from where they fought a bitter defensive battle over the month of August. The Finns were unable to provide much in the way of assistance as they themselves were holding off a massive Soviet offensive along the entire Front Line, from the White Sea to the Gulf of Finland. At the last, the surviving Estonian forces, together with as many civilians as possible, were evacuated from the Tallinn Redoubt in a seaborne operation by the Merivoimat that again, has gone down in military history as a classic example of its kind. Reek commanded the Estonian forces in Tallinn to the end, and was one of the last Estonian soldiers to board ship.

Finnish negotiations to end Finland’s war with the USSR were unable to bring any relief to Estonia and in Finland, the surviving Estonian Army forces were regrouped into the Maavoimat’s 31st Field Infantry Division (made up of JR200, JR201 and JR201) where they watched and waited through the grim days of the Soviet occupation of their homeland. There was momentary relief as the German’s attacked the Soviet Union and occupied their homeland, but this was followed by the dawning realization that the German plans for Estonia differed little from those of the Soviet Union. On the Finnish attack on the German occupiers of Estonia in April 1944, the Estonian 31st Division under Reek led the way in the liberation of their homeland. Reek continued to command the 31st Field Infantry Division as the Maavoimat moved southwards rapidly, taking the Germans from the rear and racing the Red Army to successfully liberate Latvia and Lithuania before the Red Army advance reached that far. He continued to command the 31st Field Infantry Division in the relief of Warsaw and then onwards towards Berlin. Reek was killed in action in April 1945 by Red Army forces as, leading his Division from the front as was his usual practice, he ordered his men into action to protect German civilian refugee columns who were being attacked and massacred by Red Army units. With Reek’s death in action at Russian hands, the Estonian 31st Division responded with an all-out attack on all Red Army units in their vicinity, an action in which Kenraaliluutnantti Ruben Lagus’ 21st Pansaaridivisoona, the Polish 1st Armoured Division and the Maavoimat’s 8th Infantry Division happily joined in. Only the personal and forceful intervention of Kenraaliluutnantti Oesch prevented the situation from escalating further.

The Finnish R&D Program accelerated through 1939 and into the War, as we will see in this and in subsequent Posts. In the remainder of this Post, we will cover two Finnish R&D Programs which would prove to be invaluable – the first being the development and production of the Kynnel Radio, which was used by all Finnish units operating behind the Soviet frontline over the course of the Winter War – and the second being the Nokia one-man portable Combat Radio, which began to enter service in early 1940 – and which by the end of Summer 1940, equipped every Maavoimat Infantry Platoon.

Next Post: The Maavoimat’s “Kynnel” Long-Range Patrol Radio and the Nokia one-man Backpack Portable Combat Radio

Maavoimat Signals equipment through the 1920’s and into the 1930’s

As I mentioned a few Posts ago, please note that the content of this Post as far as OTL Finnish Army Radio and Signal’s equipment (and photos) is concerned is sourced from Antero Tanninen’s wonderfully detailed website, http://personal.inet.fi/koti/antero.tanninen/ - and more specifically, http://personal.inet.fi/koti/antero.tanninen/Radiotaulukko.htm - and is reused with Antero’s permission. If you’re interested in Finnish Radio equipment, Antero’s site goes into this subject in far greater detail than I’ve used – the content is primarily in Finnish but if you use Google Translate, you’ll get a pretty good idea of what it’s all about.

Suomen Maavoimat war-time field radios and field telephone / switchboard equipment at the time of the Winter War.

Note that this is not a complete listing of WW2 Maavoimat Radios, as the Maavoimat ended up with a wide range of equipment from many different sources – but it does give you an idea of the type of equipment that was in use as well as its capabilities.

In general terms, there were four types of Field Radios that were in common use by the Maavoimat. These were the:

AB-Radio: Used by the higher echelons of the Maavoimat (Army Bases, Headquarters, etc) for communications over very long distances;

B-Radio: Used at Corps, Division and Regimental Headquarters for commmunications between Headquarters units;

C-Radio: Radio communications within the Infantry Regiment and at Battalion HQ Level for the Battalions and major supporting units that make up a Regiment

D-Radio: Infantry Company, Artillery Fire Control, Close Air Support and smaller units within the Regiment.

Below, as well as examples of Field Telephones, we will list examples of each type of Field Radio together with capabilities (and photos).

Field Telephone and Field Telephone Switchboard Equipment

Two early-model Field Telephones used by the Maavoimat: The top phone is a Siemens & Halsken produced field telephone model "Grosser Feldfernsprecher" made in 1917. The phone in the lower image is also a Siemens & Halsken – a "Feldfernsprecher" model from 1916. These remained in service with the Maavoimat until 1939, after which they were replaced by the new models. However, with the Winter War, they remained in stock as war reserve material and were used to replace combat losses.

Virolaisen kenttäpuhelimen vanhempi malli 1920 vuoden loppupuolelta. Valmistaja Tartu Telefoni Vabrik. / Field Telephone manufactured for the Maavoimat by Tartu Telefonika of Estonia (at this stage not yet owned by Nokia) – an older P-1-8 1920 model.

Field phones boxes were originally made of hardwood such as oak. Wood as a construction material was however relatively expensive and ill-suited to mass production. Thus, in the 1930’s, resin’s quickly replaced wood as the material of choice for casings. Bakelite was perfectly suited to mass production because the cases could be made using die-casting molds. This Field Telephone was one for the early models constructed with a bakelite casing. The cases were also more robust, lighter and more waterproof than the older wood cases.

Suomen armeijan toisessa maailmansodassa käytössä ollut Helvarin sotilasradio. Luultavasti P-12-12u "Kukkopilli" malli. Kuvattu Hangon rintamamuseossa / Helvar military radio-telephone used by Finnish army in World War 2. Likely a P-12-12u "Kukkopilli" model. Photographed in Hanko front museum.

The Early Days of Radio in the Maavoimat

But first, an explanation of the Finnish four or five digit device code that you will see associated with almost all Radios:

V = communications (/ signals) device

R = radio (wireless)

G = D station / radio for artillery fire control and infantry company

K = producer (and/or country of origin): ASA

[none], A, B, C... = version

Radioasema toiminnassa metsässä 1928 / A radio station operating in the woods – 1928. The figure shows a wintry forest, and two men on skis, one standing, one leaning over the sled. The leaning man is recording a message. Both men are soldiers,

As mentioned above, there were four types of Field Radios that were in common use by the Maavoimat. These were the:

AB-Radio: Used by the higher echelons of the Maavoimat (Army Bases, Headquarters, etc) for communications over very long distances;

B-Radio: Used at Corps, Division and Regimental Headquarters for commmunications between Headquarters units;

C-Radio: Radio communications within the Infantry Regiment and at Battalion HQ Level for the Battalions and major supporting units that make up a Regiment

D-Radio: Infantry Company, Artillery Fire Control, Close Air Support and smaller units within the Regiment.

The use of radio as a field artillery fire control device began to develop rapidly within the Maavoimat from about 1925. Prior to this, in 1923 General Vilho Petter Nenonen, a versatile and brilliant artillery commander of whom we will see much more, had sought to gain experience in the use of radio as an arillery fire control tool. As far as is known, at this stage no other country had carried out such experiments with the use of suitable and lightweight radio equipment for this task. Nenonen’s first experiments were carried out using heavy horse and cart-based radios. As a result of the experiments, Nenonen ordered two radio stations as a trial and these were completed in 1924. The two-man portable radios were designed to have a voice range of about 10km but on completion, it was found that the range was as much as 50-60km. The experiment resulted in further action, and on 26 May 1924 the Artillery Inspector ordered the Artillery Regiment to select from among its members one officer and one NCO for training with the Signals Branch.

In Order No 403/27.6.24, Nenonen explained to the Army C-in-C the reasons why he considered it important that the artillery should use light-weight, portable radio equipment. The statement also explained the technical requirements of stations, and suggested that each Artillery Battalion should be allocated 2 radio stations to communicate with higher headquarters, regiments and forward artillery observation and control stations. In addition Nenonen in 1925 gave the technical a written order that a Radio Battalion was to be created for experimental training purposes, and 10 portable radio stations were to be built in accordance with the already-advised specifications.

Radio stations made by the Radio Battalion, however, were still quite bulky and difficult to use. Continued work on improvements to reduce the weight and improve ease of use was carried out but it proved more or less impossible for the Radio Battalion to reduce the weight to less than 13kg. In June 1925, Nenonen presented the Radio Battalion woth a simple wiring diagram which was based on amateur radio circuit designs. Slowly, due to the bureaucracy that then reigned, the Radio Battalion built Nenonen two stations. These smaller and lighter“Perkjärvellä” radios were tested and they worked very satisfactorily for the Artillery. The new Artillery portable radio stations began to be used for LTJ-radioiksi (mobile artillery fire control). Thus, thanks to Nenonen’s foresight and the measures he took, by 1927 Finnish Field Artillery was already using portable Radios as well as wire-based communications in all peace-time exercises. In this, the Maavoimat was significantly ahead of all other militaries – and it was a lead that would continue to grow through the 1930’s, as we will see.

The A-Radio and AB-Radio

The VRBIA was large, usually permanently installed and was used by the highest formations and levels of leadership (Military HQ, Corps HQ, large Air Bases). It was also used for air and sea forces and later, by the Border Guard Department. The device operated in both short and long-wave, or both depending on the configuration. It could send both voice and telegraphy and Transmit power was hundreds of watts. The transmitter shown was usedthrough to the beginning of the 1970s.

An AB radio transmitter-receiver: This was a large Field Radio, usually transported in a Car or Trailer and operated inside a building, tent or bunker. Range was approximately 500km for Morse and about 100km for Voice. Power was provided by a Generatorwhich kept the batteries charged and three different length rubber-coated antennae were used – 8, 20 and 25 metres (the length of the antenna to be used was determined by the frequency on which the radio was to operate). The radio equipment and tools were packed in a total of four cases for transport. The full equipment weight was 462 kg.

The B-Radio

This P-12-5 B-Radio was in fact the same as a C-Radio, but built to a higher current rating. The transmitter and the receiver were in the same box.

Below, a Helvar P-12-6 (RL20) VREH “Bertaa” B-Radio

A HELVAR B station, P-12-6, VREH (B) Two-channel transmitter and receiver. The Transmit power was 20 W CW and voice-6 W. Morse range was about 200-300 km, about 60 km for speech. The Radio is a medium-duty vehicle transported, two-channel field \radio, which was carried in five shipping cases: a transmitter-receiver box, the machine converter box, 2 boxes for the batteries and battery charger and the generator which powered the battery charger. The Equipment weighed a total of 185 kg without the battery charger. The radio was equipped with two rubber-coated antenna with a length, of 20 and 10 m and a 3-arm 3 x 8m long rubber-coated counterweight. The antenna length was chosen dependent on the working frequency selected.

The C-Radio and the C-D Radio

C-Radio: Powered by a 4.5 V battery, this was both a Voice and Morse Transmitter-Receiver.

C-D Radio: This was a portable two-channel field radio. The transmitter and receiver are in different boxes. The power supply and accessories are housed in four cases in total. Range was 30 km for morse and 15 km for speech. The equipment weighed 65 kg in total and was powred from batteries charged from a small generator.

The D-Radio

D-Radio station. The photo was taken at Santahamina on 21 October 1932. The Radio belonged to 1/Kenttätykistörykmentti 3

The D and C radio receivers were similar, but the D-station transmitter, however, was completely different from the C- radio. (Image above is the receiver.) The antenna was made of metal tubing and was a collapsible loop antenna, which is attached to the box sides. The antenna is shown in the upper image (slightly). Power source was a 4.5 V light battery, which was placed in a separate battery box. The transmitter could be used for speech, as well as for morse. The angle of the Ring antenna was manually adjusted to achieve optimum reception.

Suomalainen P-12-15 VRGK sotilasradio. D-luokan eli tykistön tulenjohtoradio, valmistanut ASA vuonna 1941. Antenniteho 0,4 W, taajuusalue 4,6-6,6 MHz, yhteysväli sähkötyksessä 20 km, puheyhteydessä 12 km. Kuvattu Hämeenlinnan tykistömuseossa / Finnish P-12-15 VRGK military radio. Artillery fire control (class D) radio, manufactured by ASA in 1941. Transmission power 0.4 W, frequency 4.6-6.6 MHz, wireless telegraph range 20 km, radiotelephony range 12 km. Photographed in Hämeenlinna artillery museum.

Suomalaiset VRLK (oikealla) radiovastaanotin ja VRGK sotilasradio, molemmat Asa radion valmistamia. Kuvattu Jalkaväkimuseossa / Finnish VRLK (right) radio receiver and VRGK military radio, both manufactured by ASA Radio. Photographed in Mikkeli Infantry museum.

Tornister Funkgert d2 Military Radio: The Finnish marking is VRKS, it is probably a mortar team radio, of German origin.

This is a Finnish made P-12-15 (or VRGK) portable single channel field radio (sender - receiver) produced by ASA Oy. It was classed as a "D radio" which meant it was mainly used by forward artillery observers and by infantry companies. The D-Radio could be used in telegraph (A1) and voice (A3) modes, and could be used with a separate telephone. The total weight was about 30kg, packed in two plywood boxes (one for the radio, one for the batteries). The antennae was a 10m long rubber-coated “throwable” aerial. A number of different versions were built, incorporating a number of improvements with each. The price per unit was approx. 15,000 Markka – they weren’t cheap, but despite this they equipped around half the Finnish infantry units in the Winter War, together with a large number of supporting units, air surveillance posts and the like, with some 1,800 in service in late 1939 (with a total cost of some 27,000,000 markka, this was not an insignificant cost)

The Signals Branch of the War Department – a brief history

The War Department’s Radio Telegraph Branch had been founded in the summer of 1918. It was based at the military headquarters in Mikkeli and initially consisted of the Radio School, and later included the Heavy Field Radio Division which had been formed during the civil war from radio men and willing volunteers. The Light Field Radio Department in Helsinki (based at Santahamina) later also joined the Branch. The Heavy Field Radio Department was based first at the University of Helsinki Department of Physics, but in the autumn of 1918 it was transferred to Santahamina. Conscripts began training om Signals from August 1918. The Heavy Field Radio Department’s radio station was responsible for radio communications over the whole of Finland to naval and merchant ships as well to the state-owned icebreakers.

The Branch also began to teach civilians radio and telegraph skills. In 1920, a Radio Workshop was established and both military and civilian radio communications were carried out. Signals Branch strength from 1922-1925 was between 180-250 conscripts, of whom 85% studied and completed Signals courses successfully. From 1923, the armed forces Divisional radio sets were assembled at Santahamina and in 1924 the Radio units of the Signals Branch were grouped into the newly formed Radio Battalion. At that time, the Post and Telegraph Office was taken over by civilian broadcasting, as were the the fixed point radio stations, with the Santahamina being the last position handed over in May 1925. After the transfer of the civilian radio stations, the Radiopataljoonassa (Radio Battalion) had two radiokomppaniaa, as well as both a depot and a repair workshop. By 1926, the Radiopataljoonassa strength was about 20 officers, 40 NCO’s and approximately 200-250 conscripts.

Organizing the Signals Branch:

In the early 1930’s, the Signals Branch began to be substantially reorganized as part of the overall restructuring and reorganization of the Maavoimat as a whole. Up until 1933, the Signals Branch had been combined as part of an overall scientific-technological forces grouping which consisted of the Engineers, Transport and Armoured forces as wekk as Signals. But in 1933, the Signals Branch was finally made an independent Branch of the Armed Forces and in 1934 the Signals Regiment was established, based from Viipuri, where the Signals School was also constructed. At the same time, the Signals units within the Maavoimat were reorganized at the Divisional, Regimental and Battalion level with the end result outlined below.

The Maavoimat’s combat formation signals units….

On the outbreak of the Winter War in late 1939, the Suomen Maavoimat military communications structure within a standard Division was largely organized as set out below. Keep in mind that in 1939, following a decade of organizational restructuring to optimize combat capabilities, the standard Maavoimat combat formation was a Regimental Battle Group, three of which were organized into a Division for logistical support and command oversight purposes. As such, the composition of a Regimental Battle Group was in practice intended to be flexible and suited to the assigned mission objectives: for the purposes of this post, a standard formation will be assumed (Maavoimat Unit Organisation will be covered in a separate Post or Posts).

As such, a Regimental Battle Group was intended to be a self-sufficient fighting force with all necessary supporting units integrated into its structure. Thus, many supporting formations that in other Armies were commanded at a Divisional level were, in the Maavoimat, built into the Regiment. With Signals, where other Armies had a Signals Battalion at the Divisional Level, the Maavoimat had an overstrength Signals Company at the Regimental level. Maavoimat signals structure is laid out below.

Division (Divisoona): At Divisional level, there was a Divisional Signals Commander, typically a Captain, in charge of a Divisional Signals Company (Viestikomppania, VK) and a Line Contruction Company (Linjanrakennuskomppania, LRak.K) which were intended to meet all Divisional-level signals requirements. Divisional Signals units were responsible for establishing and maintaining links to Regimental Battle Groups and to all independent units attached to the Division as well as for the establishment and maintenance of lines and radio communications to Army Corps Headquarters as well as to Divisional observation and forward artillery control aircraft (while these were Ilmavoimat aircraft, they were attached to, and under the operational command of, Maavoimat Divisional HQ’s).

Divisional Signals Company (Viestikomppania, VK)

Company Commander – Officer, usually a Captain who, when needed, could be used as a substitute for the Divisional Signal Commander

Telephone Switchboard Platoon (Keskusjoukkue)

2 Telephone Switchboard Squads

1 Field Telegraph Squad

Radio Platoon (Radiojoukkue)

6 x C-asema (C Station) (0+1+3 = 4) [4 person team per C Radio]

1 x Ilmaviestiryhmä (specialised Radio Squad for communicating with Divisional Observation and Forward Artillery Control Aircraft)

Messenger Platoon (Lähettijoukkue)

3 x Messenger Squads (Motorcycle, Bicycle or Horse messengers)

Signal Equipment Repair Shop (Viestivälinekorjaamo)

Supplies Platoon (Toimitusjoukkue)

Divisional Line Contructing Company (Linjanrakennuskomppania, LRak.K)

Company Commander – Officer, usually a Lieutenant

3 x Telephone Line Platoons (Puhelinjoukkue)

each Platoon, 3 x TelephoneSquads (responsible for laying and fixing cables)

Supplies Platoon (Toimitusjoukkue)

Regimental Battle Group: All Signals units and detachments within the Regimental Battle Group were the responsibility of a Viestikomentaja (Signals Commander), although in practice the Signals Detachments formed part of the unit they were attached too and were under the direct command of the unit commanding officer. By mid-1939, with the growth of the Signals Network, each Regimental Battle Group contained a Regimental Signals Company (Viestikomppania, VK) which was also responsible for Field Telephone Lines where these were used. In addition to Regimental signals companies there were smaller Signals Detachments (Viestielin) in attached Artillery Batteries and also with other specialized units directly under the control of Regimental HQ (examples being the Heavy Mortar, Anti-Tank and Pioneeri companies);

In Artillery Batteries and Heavy Mortar Companies, the Signals Detachments (Viestielin) were primarily responsible for the connections with Regimental and Battalion HQ’s and with the Fire Observing Squads (Tulenjohtue) attached to each Infantry Company. Signals Detachments (Viestielin) strength at the Artillery Battery / Mortar Company level was generally 8 men – 2 NCO’s and 6 Privates. The Fire Observing Squads (Tulenjohtue) were made up of 3 men – 1 NCO and 2 Privates.

Regimental Battle Group Signals Company (Viestikomppania, VK)

Company Commander – Officer, sometimes a Captain but often a Lieutenant

Telephone Platoon (Keskusjoukkue)

1 x Telephone Switchboard Squad

2 x Telephone Squads (responsible for laying and fixing cables)

Radio Platoon (Radiojoukkue)

6 x C-asema (C Station) (0+1+3 = 4) [4 person team per C Radio]

1 x Ilmaviestiryhmä (specialised Radio Squad for communicating with Divisional Observation Aircraft and Close Air Support aircraft)

Messenger Platoon (Lähettijoukkue)

3 x Messenger Squads (Motorcycle, Bicycle or Horse messengers)

Signal Equipment Repair Shop (Viestivälinekorjaamo)

Supplies Platoon (Toimitusjoukkue)

Battalion (Pataljoona): Each Battalion contained a Signals Platoon (Viestijoukkue, VJ) which was responsible for establishing radio connections and field telephone connections down to the individual Companies (and at times to Platoons) and to attached units such as the Battalion Anti-Tank Gun Platoon, Mortar Platoon and the AA Gun Platoon. Total strength of the Signals Platoon was 1 Officer + 10 NCOs + 36 men = 47 men in total. The Signals Platoon was theoretically organized as follows:

Joukkueenjohtaja (Platoon Leader - Officer)

Joukkueenvarajohtaja (Deputy Platoon Leader - NCO)

Radio Personnel: (total 0+4+12 = 16)

3 x C-asema (C Station) (0+1+3 = 4) [4 person team per C Radio]

1 x Ilmaviestiryhmä (0+1+3 = 4) (specialised Radio Squad for communicating with Divisional Observation Aircraft and Close Air Support aircraft)

Telephone personnel: (total 0+3+18 = 21)

Asemaryhmä (Station Squad) (0+1+3 = 4)

2 x Linjarakennusryhmä (Line Constucting Squad) (0+1+7 = 8)

Hevosajoneuvot (horse vehicles) (0+1+7 = 8) [6x telephone vehicles, 2x radio vehicles]

Infantry Company: There was no specific Signals Unit in an Infantry Company. Instead, the Company Command Squad (Komentoryhmä) included a 3 man Signals Team (1 NCO, 2 Privates) with a single “D” Radio. There was also a 4-Man Security and Combat Messenger Detachment made up of an NCO Combat Messenger [Aliupseeritaistelulähetti] and three Combat Messengers [Taistelulähetti] who doubled as a Company level Linjarakennusryhmä (Line Constucting Squad) responsible for running Field Telephone Lines down to the individual Infantry Platoons within the Company. In addition there were also two Combat Messengers [Taistelulähetti] for contact between company and battalion in the event that both Radios and Telephone Lines were down. Generally, there was also a Fire Observing Squad (Tulenjohtue) made up of an NCO Observer [Aliupseeritähystäjä] and two Observers [Tähystäjä] attached to each Infantry Company Command Squad (Komentoryhmä) and also equipped with a “D” Radio. Where the situation was static, there was generally a single Field Telephone with each Platoon Command Team. This was the situation at the start of the Winter War, but as the new, more compact one-man Nokia Backpack Combat Radios began to be available in mid-1940, these were issued first at the Platoon Level, with one of the new Radios per Platoon.

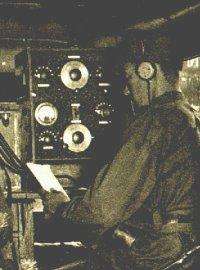

Maavoimat Lotta Svard Signals personnel operating a “B-Radio” – Summer 1940: Lotta Svard volunteers made up some 80% of rear-area Signals Personnel – With some 16,000 rear-area signals personnel, the Lotta Svard volunteers made a substantial contribution to the Maavoimat’s combat strength, freeing up enough men to form an additional 3 Regimental Battle Groups (more or less one additional Division). These Lotta’s were likely part of a Regimental Battle Group Headquarters Signals Company (Viestikomppania), although Lotta’s filled slots as far down as Battalion Signals Units.

Rear-area Signals Lotta, probably a Divisional or Corps Headquarters Signals Unit

Viestintälotat (Signals Lotta’s): Summer 1940, near the frontline. From the radio, probably part of a Battalion (Pataljoona) Signals Platoon.

And I just had to throw this in: “Mummosoti”(“War-Granny”) – don’t mess with a Finnish Grandma who used to be a front-line Viestintälotat in the Winter War – and who kept her trusty assault rifle hanging around afterward in case those pesky Russki’s decided to give it another go……. and be on your best behavior when you arrive for dinner with her granddaughter……

A signals repairman has started repairing a D-radio in the field. Photographed Summer-1940 on the Syvari, in the sector of Regimental Battle Group 56

The D-radio in action during the Winter War: The photograph is from an artillery observation post. Finnish Artillery units trained their own Signals personnel for Signals duties. There were usually 2 “D” Radios per Company at a minimum – one for communications to Battalion HQ and one for Artillery Fire Control. Where Platoons were equipped with Radios (unsual in 1939), there were at times up to 5 Radios per Company, although this was the exception and not the Rule, given that a Radio Team consisted of 3 men.

The Finnish Radio Industry Moves to a War Footing – December 1938

As has been mentioned, following the Munich Crisis of late 1938 the Government approved substantial increases in Defence Spending as well as emergency financial appropriations. Much of this funding was directed towards weapons but there was also a sizable amount budgeted for communications equipment and some directed to R&D work, with interesting results. The funds made available were largely directed towards rush orders for the production of Field Telephone and Radio Equipment that was already in service but which was required in greater numbers to ensure units were equipped up to their ToE. Initially these orders were met by a partial reduction in production for the civilian market and the addition of an extra Shift by the manufacturers in order to meet the military orders. However, with the threat of war far higher in the summer of 1939, all radio manufacturing facilities were shifted to full war production, resulting in the almost complete curtailment of production for the civilian market.

With Finnish radio manufacturers already producing radios for the military, the switch to full war production was rapid. Civilian radio manufacturing ceased, equipment specific to civilian radio production was placed in storage and output for the military doubled almost overnight. Military Radio’s were not cheap items – a standard “D” type radio for example cost in the region of 15,000 Markka. But the end result was that by the late Autumn of 1939, all military units were equipped up to the TOE with radio and field telephone equipment and supplies and a substantial war reserve had been built up. This was fortuitous as it turned out – it meant that after the fighting started, combat losses could be quickly replaced and as foreign volunteer units began to arrive, they could be equipped with standard Finnish military communications equipment.

On the eve of World War 2, all nations employed generally similar methods for military signaling. The messenger systems included foot, horse-mounted, motorcycle, automobile, airplane, homing pigeon, and the messenger dog. Visual agencies included flags, lights, panels for signaling airplanes and pyrotechnics. The electrical agencies embraced wire systems providing telephone and telegraph service, including the printing telegraph. Both radiotelephony and radiotelegraphy were in wide use, but radiotelephony for tactical military communication was still in its infancy in most countries – Finland being rather further along than most. The navies of the world entered World War 2 with highly developed radio communication systems, both telegraph and telephone, and with development under way of many electronic navigational aids. Blinker-light signaling was still widely used. The use of telephone systems and loud-speaker voice amplifiers on naval vessels had also come into common use. Air forces employed wire and radio communication to link up their bases and landing fields and had developed airborne long-range, medium-range, and short-range radio equipment for air-to-ground and air-to-air communication.

In communications electronics, World War II was in one sense similar to World War I: the most extravagant prewar estimates of military requirements soon proved to represent only a fraction of the actual demand. The need for all kinds of communication equipment and for improved quality and quantity of communications pyramided beyond the immediate capabilities of industry. An increase in manufacturing plant became vital, and research and development in the communications–electronics field was unprecedented.

The German blitzkrieg of 1940, with its highly visible use of armoured formations operating in conjunction with close air support, emphasized a new order of importance for reliable radio communication. The early development (mid-1930’s) within the Maavoimat of the combined arms infantry, artillery, and armoured team with close air support had created new requirements for split-second communication by radio among all members. Portable radio sets were provided as far down in the military echelons as the company (and by mid-1940, the Platoon). At the start of the Winter War, every Maavoimat tank was equipped with at least one radio and in some command tanks as many as three. Multiconductor cables provided wire communications; they could be reeled out rapidly and as many as four conversations could take place on them simultaneously through the use of carrier telephony. The Finns were, after the Germans, the first to use this type of military long-range cable. High-powered mobile radio sets were pervasive within the Maavoimat at Division, Regimental Battle Group and even at Battalion level where the Battalion operated independantly. With these sets telegraph communication could be conducted at distances of more than 100 miles (160 kilometres) with vehicles in normal motion on the road. Major telephone switchboards of much greater capacity were needed and by late 1939 these were developed, manufactured, and issued for use at all Maavoimat tactical headquarters to satisfy the need for the greatly increased number of telephone channels required to coordinate the movements of field units whose mobility had been expanded many times.

Radio relay, born of the necessity for mobility, became the outstanding communication development of World War II. Sets employing frequency modulation and carrier techniques were developed by Nokia post Winter-War and used, as were also radio relay sets that used radar pulse transmission and reception techniques and multiplex time-division methods for obtaining many voice channels from one radio carrier. Nokia designed and developed radio relay, telephone and teletypewriter circuits spanned the Gulf of Finland after the invasion of Estonia (E-Day) in late April 1944 and later furnished critically important communication services for Kenraaliluutnantti (Lt-Gen) Karl Lennart Oesch, after his breakout from the Estonia beachhead.

Commander of the E-Day Invasion, Kenraaliluutnantti Karl Lennart Oesch (on the left) monitors the situation in the Estonian beachhead, early May 1944. The commander of the Maavoimat’s Estonian 31st Field Infantry Division, Lt-Gen Nikolai Reek stands second from the right.

Nikolai Reek (Estonian Cross of Liberty, Latvian Order of Lāčplēsis, Polish Order of the White Eagle, Lithuanian Grand Cross of the Order of Vytautas the Great, Mannerheim Cross, 2nd Class (posthumous)): born Nikolai Bazõkov; February 1, 1890 Tallinn, Estonia – April 8, 1945 Germany) was commander of the Maavoimat’s Estonian 31st Field Infantry Division in the E-Day landings of late April 1944 along the Estonian coastline which took the Germany Army (and the Red Army for that matter) by surprise. An Estonian military commander during the Estonian War of Independence, Reek graduated from the Tasarist Russian Chuguyev Military Academy in 1910. He fought in World War I, and in 1917 graduated from the Imperial Nicholas Military Academy. Reek joined Estonian units in 1917 and was Estonian Army Chief of Staff until dissolution of these units. After that he organized the Estonian Defence League in Virumaa. In the Estonian Liberation War Reek was firstly commander of the 5th regiment on the Viru Front and then in January 1919 he became Chief of Staff of the 1st Division. In April he became Chief of Staff of the 3rd Division. Reek played an important role in winning the war against the Baltische Landeswehr. In September 1919 he was promoted to Colonel and served as Chief of Staff on the Viru Front. After the war Reek repeatedly served in positions of Estonian Army Chief of Staff, Minister of Defence and Commander of the 2nd Division. In 1938 Reek was promoted to Lieutenant General.

In September 1939, when Estonia reluctantly agreed to allow 25,000 Red Army troops to be based on Estonian soil, Reek was once again Commander of the Estonian Army’s 2nd Divison. With the Estonian Army’s 5 Infantry Divisions (mostly Reservists) fully mobilized over late 1939 and into early 1940 and in complete sympathy with Finland as the Winter War was fought, Stalin had ordered the seizing of Estonia in the Summer of 1940 despite, or perhaps because of, the hammering that the Red Army was taking from the Maavoimat. The Red Army assembled 160,000 men, supported by 600 tanks and 1,150 aircraft. The Soviet NKVD was ordered to be ready for the reception of 100,000 Estonian prisoners of war. On 13 June 1940, Soviet forces began to move.

The Soviets had seemingly learnt nothing from the debacle of their attack on Finland. The entire tale is for another day, suffice it to say that Reek led the Estonian Army’s 2nd Division in the defense of the western sector of the Latvian Front, fighting a withdrawal battle that has gone done in history as a classic example of a successful fighting retreat against overwhelming odds. With the Narva Line holding the eastern flank of Estonia’s defences almost to the end, the Estonian forces over the month of July 1940 slowly fell back on the Tallinn Redoubt, from where they fought a bitter defensive battle over the month of August. The Finns were unable to provide much in the way of assistance as they themselves were holding off a massive Soviet offensive along the entire Front Line, from the White Sea to the Gulf of Finland. At the last, the surviving Estonian forces, together with as many civilians as possible, were evacuated from the Tallinn Redoubt in a seaborne operation by the Merivoimat that again, has gone down in military history as a classic example of its kind. Reek commanded the Estonian forces in Tallinn to the end, and was one of the last Estonian soldiers to board ship.

Finnish negotiations to end Finland’s war with the USSR were unable to bring any relief to Estonia and in Finland, the surviving Estonian Army forces were regrouped into the Maavoimat’s 31st Field Infantry Division (made up of JR200, JR201 and JR201) where they watched and waited through the grim days of the Soviet occupation of their homeland. There was momentary relief as the German’s attacked the Soviet Union and occupied their homeland, but this was followed by the dawning realization that the German plans for Estonia differed little from those of the Soviet Union. On the Finnish attack on the German occupiers of Estonia in April 1944, the Estonian 31st Division under Reek led the way in the liberation of their homeland. Reek continued to command the 31st Field Infantry Division as the Maavoimat moved southwards rapidly, taking the Germans from the rear and racing the Red Army to successfully liberate Latvia and Lithuania before the Red Army advance reached that far. He continued to command the 31st Field Infantry Division in the relief of Warsaw and then onwards towards Berlin. Reek was killed in action in April 1945 by Red Army forces as, leading his Division from the front as was his usual practice, he ordered his men into action to protect German civilian refugee columns who were being attacked and massacred by Red Army units. With Reek’s death in action at Russian hands, the Estonian 31st Division responded with an all-out attack on all Red Army units in their vicinity, an action in which Kenraaliluutnantti Ruben Lagus’ 21st Pansaaridivisoona, the Polish 1st Armoured Division and the Maavoimat’s 8th Infantry Division happily joined in. Only the personal and forceful intervention of Kenraaliluutnantti Oesch prevented the situation from escalating further.

The Finnish R&D Program accelerated through 1939 and into the War, as we will see in this and in subsequent Posts. In the remainder of this Post, we will cover two Finnish R&D Programs which would prove to be invaluable – the first being the development and production of the Kynnel Radio, which was used by all Finnish units operating behind the Soviet frontline over the course of the Winter War – and the second being the Nokia one-man portable Combat Radio, which began to enter service in early 1940 – and which by the end of Summer 1940, equipped every Maavoimat Infantry Platoon.

Next Post: The Maavoimat’s “Kynnel” Long-Range Patrol Radio and the Nokia one-man Backpack Portable Combat Radio