You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

What If - Finland had been prepared for the Winter War?

- Thread starter CanKiwi

- Start date

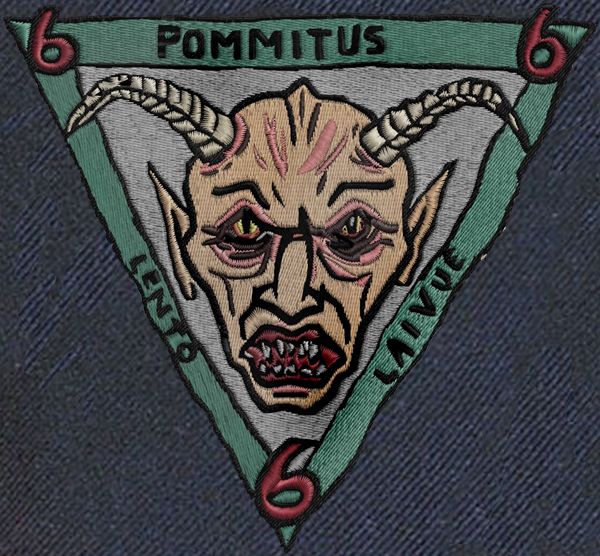

You just made my unit crest invalid, thank you so much

Edited: I corrected the crest.

My mistake originally!

However, "Originally sketched free-hand in a rare moment of quiet shortly after the commencement of hostilities between the SU and (as it then seemed) little defenceless Finland by then-Yliluutnantti Erkki Tempponen, the B/N of the squadron CO's plane (who was unfortunately dyslexic and to the amusement of the rest of the squadron personnel, always had problems with his spelling - and as a result was the butt of many jokes - the original drawing reflected this, but while the spelling was correct on almost every aircraft in the Squadron, Tempponen's was painted with his original spelling to the amusement of everyone, including Tempponen, who had long learned to live with the problem).

The corrected unit crest is shown previously, Temponnen (who over the course of the war became known by the nickname of Temppunen, "the Tricky!"). Temponnen's original, complete with dyslexix spelling, is shown below. Below is a scan of the original paper sketch on display at the Finnish Winter War museum in Tampere"

BTW, thx again for these Jotun, this is a classic unit crest - and I was planning a bit of Finnish heavy metal later on in the actual war!

Why shouldn't they. I imagine this could well be a tradition copied from the Brits or Americans pre-war...

Is that an actual patch you made or a computer-generated approximation?Awesome!

I believe there were some unit patches worn in uniforms, but checking to see. In any case, this is an ATL and if not, they can sure wear them in this timeline

Thanks to you both for the outstanding artwork......

and from axishistory where I also post this thread...

by John Hilly on Today, 19:04

An ugly looking bastard indeed!

Must be "Vanha Vihtahousu" - "The Old Devil Himself"!

Again a Finnish expression almost impossible to translate.

Terveisin...............Juha-Pekka

“Die Blechtrommel trommelt noch !!“

Redrawn clearly, vectorized and computer generated with a special prog that turns vector graphics into stitchings, and a bit of photoshop. The fabric background is a bit of the M27 finnish air force uniform. ( http://www.rathbonemuseum.com/FINN/FINM27Lt/FINM27LT.html )

Feel free to use it.

Feel free to use it.

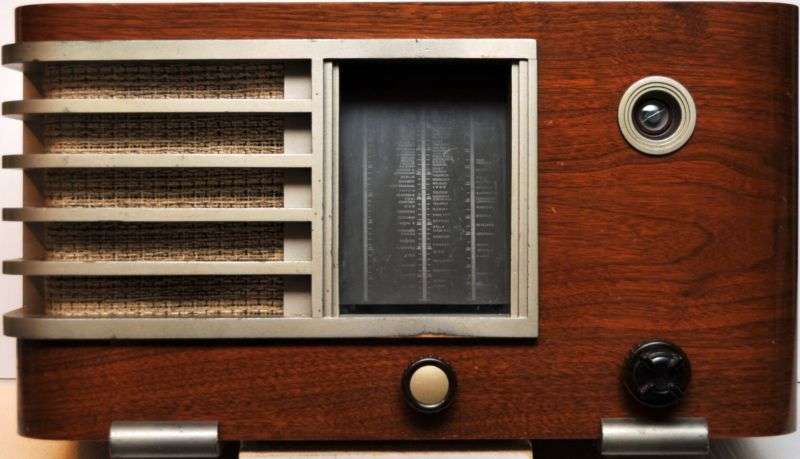

Radios / Signals in the Suomen Maavoimat - Part I

The early origins of Radio

It’s hard to imagine what military communications were like before the radio, which in turn was derived from the electric telegraph – which in turn had its origins in the earlier optical semaphore systems. Such optical signal systems have been in existence in one form or another for centuries and were faster than the physical transfer of messages by horse-rider or runner. The distance thry could bridge was however limited by geography and weather; thus, in practical use, most optical semaphore systems used lines of relay stations to bridge longer distances. The first comprehensive non-electric optical semaphore telegraph system was invented by Claude Chappe for the French military in 1794. This system was visual and used semaphore, a flag-based alphabet, depended on a line of sight for communication and was widely adopted across Europe for both commercial and military use. They succeeded in covering France with a network of 556 stations stretching a total distance of 4,800 kilometres which was used for military and national communications until the 1850s.

Sweden was the second country in the world, after France, to introduce an optical sempahore network. The Swedish network was restricted to the archipelagoes of Stockholm, Gothenburg and Karlskrona. Like its French counterpart, it was mainly used for military purposes. In the UK, Lord George Murray, stimulated by reports of the Chappe semaphore, proposed a system of visual telegraphy to the British Admiralty in 1795. A Rev. Mr Gamble also proposed two alternative systems in the same year. The British Admiralty accepted Murray's system in September 1795, and the first system was the 15 site chain from London to Deal. Messages passed from London to Deal in about sixty seconds (a distance of 68 miles), and sixty-five sites were in use by 1808. Once it had proved its success, the optical semaphore system was imitated in many other countries, especially after it was used by Napoleon to coordinate his empire and army. In most of these countries, the postal authorities operated the semaphore lines.

In Canada, the first semaphore line in North America was in operation by 1800, running between the city of Halifax and the town of Annapolis in Nova Scotia, and across the Bay of Fundy to Saint John and Fredericton in New Brunswick. In 1801, the Danish post office installed a semaphore line across the Great Belt strait, Storebæltstelegrafen, between the islands Funen and Zealand with stations at Nyborg on Funen, on the small island Sprogø in the middle of the strait, and at Korsør on Zealand. It was in use until 1865. The Kingdom of Prussia began with a line 750 kilometres long between Berlin and Coblenz in 1833, and in Russia, Tsar Nicolas I inaugurated the line between Moscow and Warsaw (1200 km) in 1833; this needed 220 stations manned by 1320 operators. In the United States the first semaphore system was a 104-kilometre line connecting Martha's Vineyard with Boston, and its purpose was to transmit news about shipping. One of the principal hills in San Francisco, California is also named "Telegraph Hill", after the semaphore telegraph which was established there in 1849 to signal the arrival of ships into San Francisco Bay.

The semaphores were successful enough that Samuel Morse failed to sell the electrical telegraph to the French government. However, France finally committed to replace semaphores with electric telegraphs in 1846. The last stationary semaphore link in regular service was in Sweden, connecting an island to a mainland telegraph line. It finally went out of service in 1880. In general terms, the old sempahore systems were quickly superceded by electric telegraph systems after these became commercially viable. While today the electric telegraph is a virtually forgotten and outdated communication system that transmitted electric signals over wires from location to location that translated into a message, 130 years ago it was as revolutionary as the Internet is today and was the direct ancestor of both the telephone and the radio – two devices that revolutionsed military communications.

While the electric telegraph itself had its origins some 250 years ago (in 1746 the French scientist, Abbé Jean-Antoine Nollet, gathered about two hundred monks into a circle about a mile (1.6 km) in circumference, with pieces of iron wire connecting them. He then discharged a battery of Leyden jars through the human chain and observed that each man reacted at substantially the same time to the electric shock, showing that the speed of electricity's propagation was very high) and there were many intermediate steps along the way, it only became a commercially practical means of communication in the 1840’s. Knowledge and commercial application of the telegraph percolated quickly throughout North America and Europe, and development of the technology was rapid. In the UK, the electric telegraph entered commercial use on the Great Western Railway over the 13 miles (21 km) from Paddington station to West Drayton on 9 April 1839 while in the USA, the first commercial telegraph line in the United States ran along a railroad right-of-way between Lancaster and Harrisburg, Pennsylvania in 1845. Dispatching trains by telegraph started in the USA in 1851, the same year Western Union began business. On 24 October 1861, the first transcontinental telegraph system was established. Spanning North America, an existing network in the eastern United States was connected to the small network in California by a link between Omaha and Carson City via Salt Lake City.

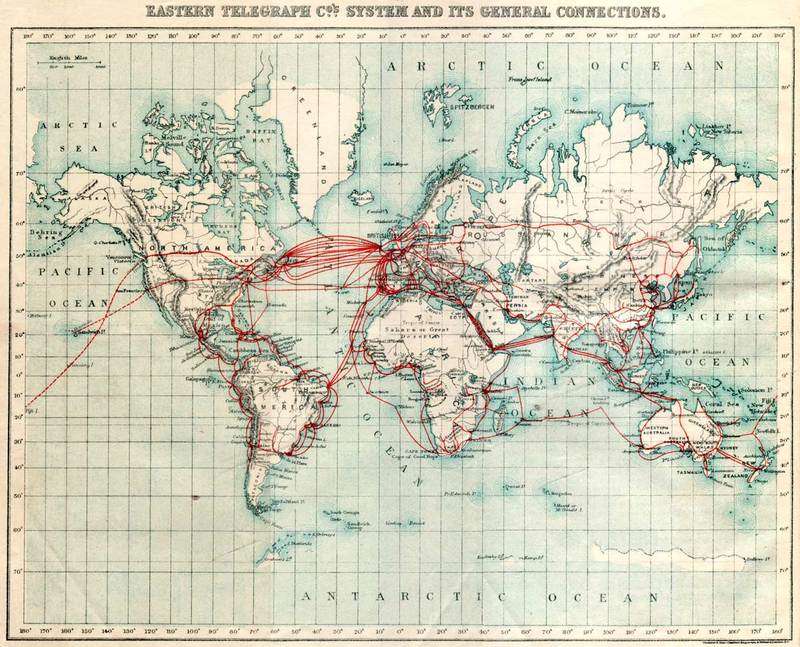

Experiments with a transatlantic telegraph cable began in 1857 and 1858, but these failed after only a few days or weeks – but by 1866 a working transatlantic telegraph cable was successfully in operation. Within 29 years of its first commercial introduction, the telegraph network connected every continent in the world except Antarctica, making instant global communication possible for the first time. The telegraph thus liberated information transfer from transportation.

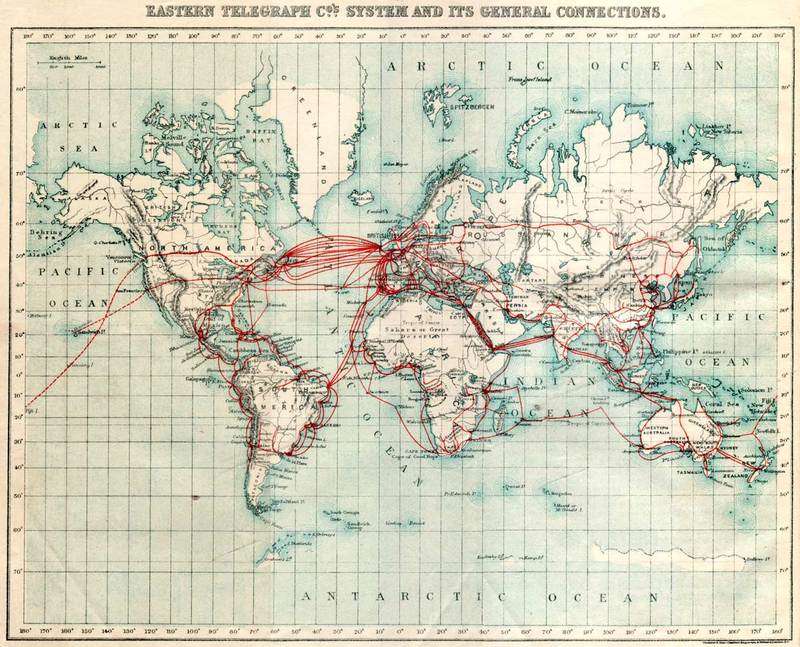

World Map of Undersea Cables from 1901

Early military utilization of the Electric Telegraph

Military organizations were quick to see the utility of the electric telegraph, with the first such recorded use in war being during the Crimean War between Russia, Britain and France. A combined British and French force landed in the Crimea and began a long-term siege of the city and naval base of Sebastopol. Britian, the home of the “Industrial Revolution” put its industrial skills to use in warfare through a series of different applications of engineering knowhow - the railway contractor Morton Peto and his partner Thomas Brassey created a Railway Construction Corps from their own army of labourers and built a full-scale railway from the base port at Balaklava to the front line. The mining industry in Leeds contributed two steam engines to work it. Joseph Paxton, architect of the Crystal Palace, organised an Army Works Corps to erect a township of wooden huts to protect the troops in the bitter winter. I K Brunel, the railway engineer, designed and had built a huge hospital from prefabricated components. William Fairbairn, the ironmaster and shipbuilder, constructed a pair of floating workshops to undertake all manner of repair and maintenance tasks for the besieging army.

The telegraph companies and their suppliers joined in with this war euphoria. In late 1854, the government in London created a military Telegraph Detachment for the Army commanded by an officer of the Royal Engineers. It was to comprise twenty-five men from the Royal Corps of Sappers & Miners, a cadre of which were trained by the Electric Telegraph Company to construct and work the first Field Electric Telegraph, as it was called.

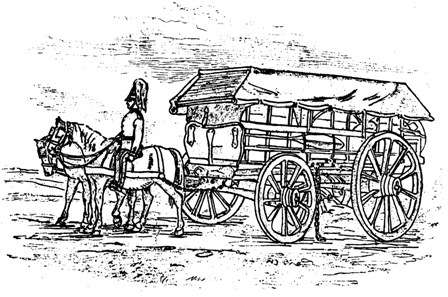

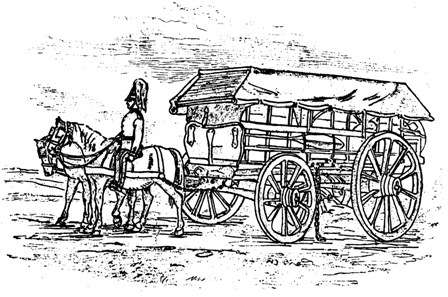

The Electric Telegraph Company’s War Wagon 1854: The outfit for the first war telegraph, usually hauled by three pair of horses, even had a gutta percha boat inverted on the top. The sketch shows a heavy cavalry trooper riding postillion rather than a sapper.

The Telegraph Detachment’s lines allowed Lord Raglan (the C-in-C) to communicate within a few minutes with his generals at any time and the Telegraph Detachment eventually possessed eight Field Electric Telegraph stations, 24 miles of line around Sebastopol, connecting the Headquarters, Kazach, the Monastery, the Engineer Park, the Right Attack, the Light Division, Kadikoi and Balaklava.. A temporary 310 mile long submarine cable also connected British headquarters in Balaklava to Varna in Turkish Bulgaria. This connected to the European circuits via a French Army-built land line to existing Austrian circuits at Bucharest, hence to London and Paris in autumn 1855. A cable for the British government was also run from Varna direct to Constantinople, the Turkish capital, where another land circuit existed to Vienna and the European capitals.

After the Crimea, the British Army rapidly adopted the electrical telegraph for internal communication in its fortresses at Malta and then at Gibraltar, then elsewhere in the late 1850s. Three years after the Crimean War, in the Indian Mutiny, the newly established telegraph, which was controlled by the British, was a deciding factor. The Royal Engineers also despatched telegraph detachments, similar to those assembled for the Crimea, with the expeditions to China in 1859 and Hazara in Afghanistan during 1868. The French Empire had learned from observing their allies in the British Army during the Crimea war and for their brief and bloody campaign in northern Italy against Austria in 1859 they organised a “service télégraphiques” which laid 400 kilometres of line and created thirty-five telegraph stations along the advance to keep the army in touch with metropolitan France. It was claimed that at the decisive battle of Solferino on June 24, 1859 “the movement of the whole army was known and regulated like clockwork” by telegraph.

Between October 1859 and April 1860 Spain was at war with Morocco, with an army under General Leopoldo O’Donnell based from the Spanish enclave of Ceuta. The Royal government in Madrid commissioned a war telegraph, the largest element of which was a 25 mile underwater cable linking the mainland at Tarifa, near Algeciras, across the Mediterranean to Ceuta on the Moroccan coast. Use was also made of Field Telegraph detachments.

(please note that most of the above military telegraph information was sourced from http://distantwriting.co.uk/default.aspx, “A History of the Telegraph Companies in Britain between 1838 and 1868 by Robert Stevens – the site has a vast amount of really interested information on the Electric Telegraph in Britain)

In the American Civil War (1861–65), wide use was made of the electric telegraph. In addition to its employment in spanning long distances under the civilian-manned military telegraph organization, a mobile field service was provided in the Union army by wagon trains equipped with insulated wire and lightweight poles for the rapid laying of telegraph lines. Immediately before and during the Civil War visual signaling also received added impetus through the development of a system applying the Morse code of dots and dashes that spelled out messages with flags by day and lights or torches by night. Another development for light signaling placed a movable shutter, controlled by a key, in front of a strong light. An operator, opening and closing the shutter, could produce short and long flashes to spell out messages in Morse code.

Simultaneously, the Prussian and French armies also organized mobile telegraph trains. During the short, decisive Prussian campaign against Austria in 1866, field telegraphs enabled Count Helmuth von Moltke, the Prussian commander, to exercise command over his distant armies. Soon afterward the British organized their first permanent field telegraph units in the Royal Engineers. Until 1877, all rapid long-distance communication depended upon the telegraph. That year, a rival technology developed that would again change the face of communication -- the telephone. The invention of the telephone in 1876 was not followed immediately by its adoption and adaptation for military use. This was probably due to the fact that the compelling stimulation of war was not present and to the fact that the development of reliable long-distance telephone communication was not achieved for many years. The telephone was used by the U.S. Army in the Spanish-American War, by the British in the South African (Boer) War, and by the Japanese in the Russo-Japanese War. This military use was not extensive, and it made little material contribution to the development of voice telephony. Before the outbreak of World War I, military adaptation of the telephone did take place, but its period of growth had not yet arrived.

Near the close of the 19th century, a new means of military signal communication made its appearance—the wireless telegraph, or radio. The major powers throughout the world were quick to see the wonderful possibilities for military and naval signaling. Development was rapid and continuous, and, by 1914, it was adopted and in extensive use by all the armies and navies of the world. It soon became apparent that wireless telegraphy was not an unmixed blessing to armies and navies, because it lacked secrecy and messages could be heard by the enemy as well as by friendly forces. This led to the development of extensive and complicated codes and ciphers as necessary adjuncts to military signaling. The struggle between the cryptographer and the cryptanalyst expanded greatly with the adoption of radio and continued to be a major factor affecting its military use.

Military usage and evolution of telephone and radios in WW1

The onset of World War I found the opposing armies equipped to a varying degree with modern means of signal communication but with little appreciation of the enormous load that signal systems must carry to maintain control of the huge forces that were set in motion. The organization and efficiency of the armies varied greatly. At one end of the scale was Great Britain, with a small but highly developed signal service; and at the other end stood Russia, with a signal service inferior to that of the Union Army at the close of the American Civil War. The fact that commanders could not control, coordinate, and direct huge modern armies without efficient signal communication quickly became apparent to both the Allies and the Central Powers. The Germans, despite years of concentration on the Schlieffen Plan, failed to provide adequately for communication between higher headquarters and the rapidly marching armies of the right wing driving through Belgium and northern France. This resulted in a lack of coordination between these armies, which caused a miscarriage of the plan, a forced halt in the German advance, and the subsequent withdrawal north of the Marne. On the Allied side, the debacle of the Russian forces in East Prussia — a crushing defeat of the Starist Russian Army at the hands of General Paul von Hindenburg in the Battle of Tannenberg — was in large part due to an almost total lack of effective signals communication by the Russian forces.

As the war progressed there was a growing appreciation of the need for improved electrical communications of much greater capacity for the larger units and of the need within regiments for electrical communications, which had heretofore been regarded as unessential and impractical. Field telephones and switchboards were soon developed, and those already in existence were improved. An intricate system of telephone lines involving thousands of miles of wire soon appeared on each side. Pole lines with many crossarms and circuits came into being in the rear of the opposing armies, and buried cables and wires were laid in the elaborate trench systems leading to the forwardmost outposts. The main arteries running from the rear to the forward trenches were crossed by lateral cable routes roughly parallel to the front. Thus, there grew an immense gridwork of deep buried cables, particularly on the German side and in the British sectors of the Allied side, with underground junction boxes and test points every few hundred yards. The French used deep buried cable to some extent but generally preferred to string their telephone lines on wooden supports set against the walls of deep open trenches. Thus electrical communication in the form of the telephone and telegraph gradually extended to the smaller units until front-line platoons were frequently kept in touch with their company headquarters through these mediums.

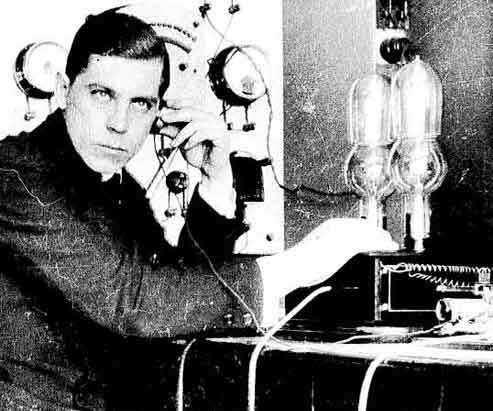

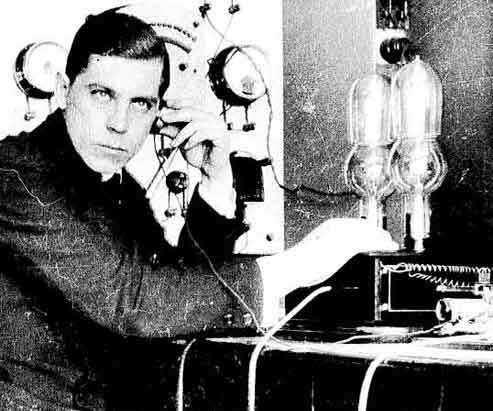

Radio Equipment in a WW1 Dugout

Marconi Trench Set

Marconi Motorcycle Set

Marconi Pack Set

Marconi Wireless Pack Set

Marconi Horse Set

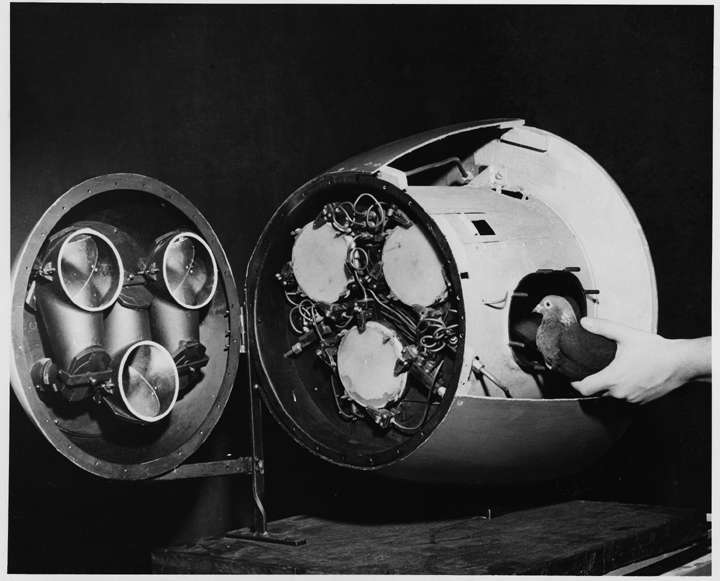

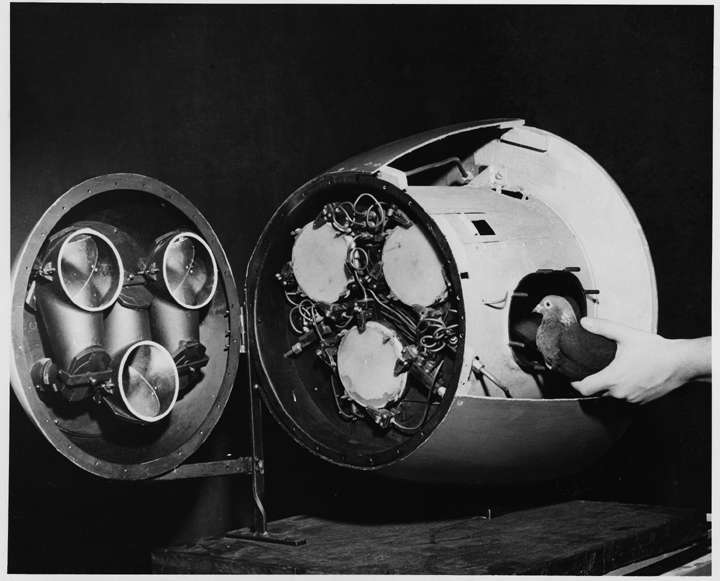

Despite efforts to protect the wire lines, they were frequently cut at critical times as the result of the intense artillery fire. This led all the belligerents to develop and use radio (wireless) as an alternate means of communication. Prewar radio sets were too heavy and bulky to be taken into the trenches, and they also required large and highly visible aerials. Radio engineers of the belligerent nations soon developed smaller and more portable sets powered by storage batteries and using low, inconspicuous aerials. Although radio equipment came to be issued to the headquarters of all units, including battalions, the ease of enemy interception, the requirements for cryptographing or encoding messages, and the inherent unreliability of these early systems caused them to be regarded as strictly auxiliary to the wire system and reserved for emergency use when the wire lines were cut. Visual signaling returned to the battlefield in World War I with the use of electric signal lamps. Pyrotechnics, rockets, Very pistols, and flares had a wide use for transmitting prearranged signals. Messenger service came to be highly developed, and motorcycle, bicycle, and automobile messenger service was employed. Homing pigeons were used extensively as one-way messengers from front to rear and acquitted themselves extremely well. Dogs were also used as messengers and, in the German army, reached a high degree of efficiency.

A new element in warfare, the airplane, introduced in World War I, immediately posed a problem in communication. During most of the war, communication between ground and air was difficult and elementary. To make his reports the pilot had to land or drop messages, and he received instructions while in the air from strips of white and black cloth called “panels” laid out in an open field according to prearranged designs. Extensive efforts were made to use radiotelegraph and radiotelephone between the airplanes and ground headquarters. The closing stages of the war saw many planes equipped with radio, but the service was never entirely satisfactory or reliable and had little influence on military operations. During World War I however, wireless telegraph (radio) communication was employed extensively by the navies of the world and had a major influence on the character of naval warfare. High-powered shore and ship stations made wireless communication over long distances possible. One of the war lessons learned by most of the major nations was the compelling need for scientific research and development of radio equipment and techniques for military purposes.

An over-view of Inter-war Developments.

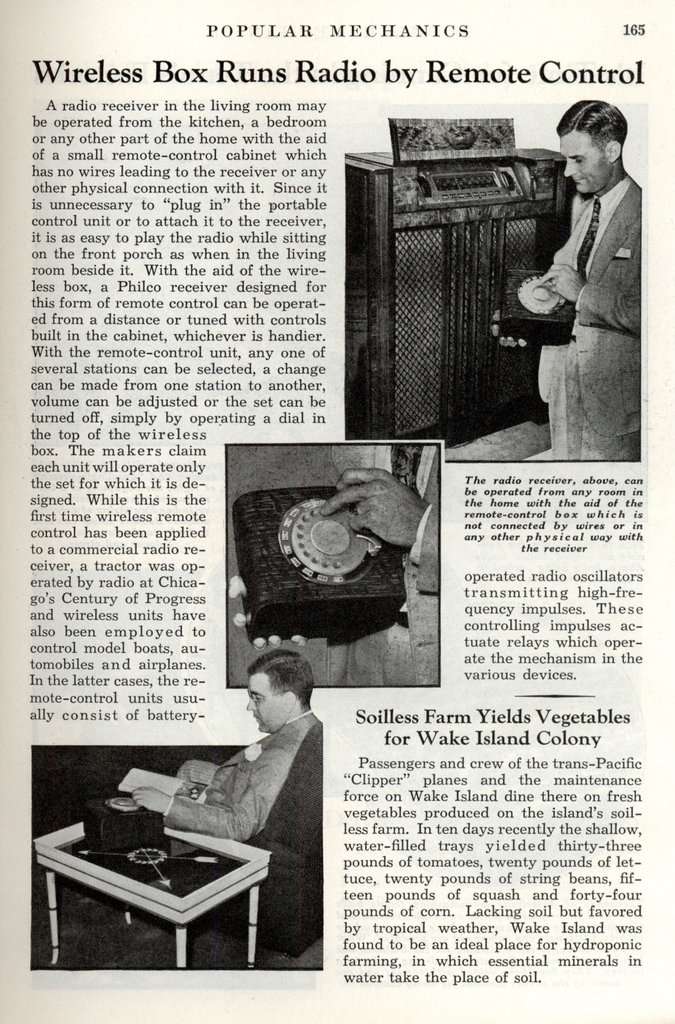

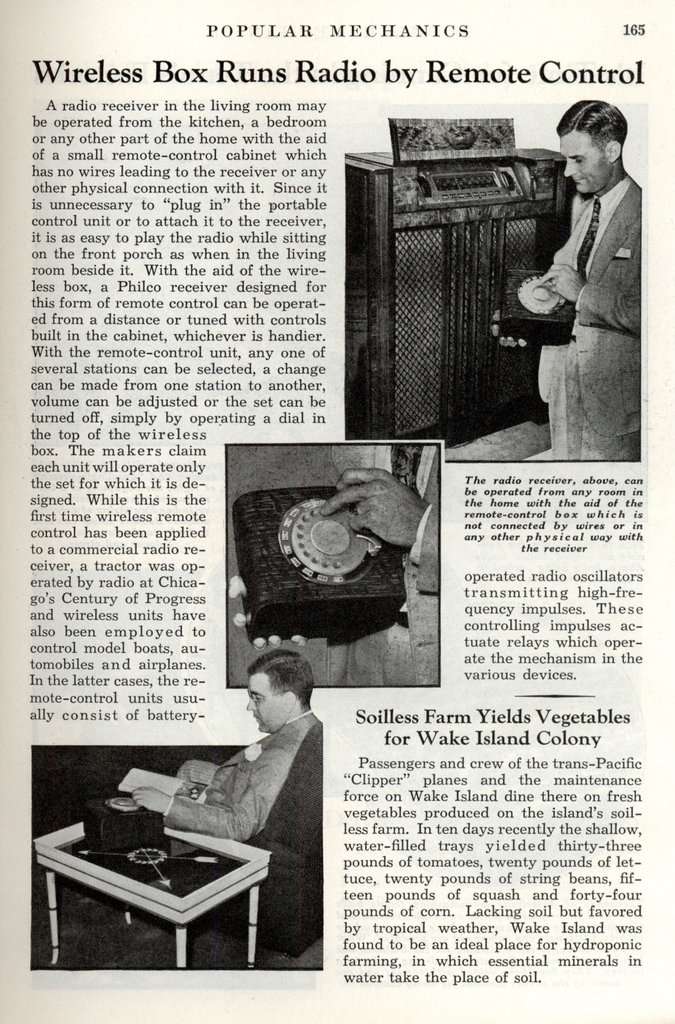

Although the amount of funds devoted to military development during the period from World War I to World War II was relatively small, the modest expenditures served to establish a bond between industry, science, and the armed forces of the major nations. Of great importance in postwar radio communication was the pioneering by amateurs and by industry and science in the use of very high frequencies. These developments opened up to the armed services the possibilities of portable short-range equipment for mobile and portable tactical use by armies, navies, and air forces. Military work in these fields was carried out actively in Germany, Great Britain and the United States among others. Of the major powers, Germany as early as 1938 had completed the design and manufacture of a complete line of portable and mobile radio equipment for its army and air force.

Between World Wars I and II the printing telegraph, commonly known as the teleprinter or teletypewriter machine, came into civilian use and was incorporated in military wire-communication systems, but military networks were not extensive. Before World War II, military radioteleprinter circuits were nonexistent. Another major communication advance that had its origin and early growth during the period between World Wars I and II was frequency-modulated (FM) radio. Developed during the late 1920s and early 1930s by Edwin H. Armstrong, an inventor and a major in the U.S. Army Signal Corps during World War I, this new method of modulation offered heretofore unattainable reduction of the effect of ignition and other noises encountered in radios used in vehicles. It was first adapted for military use by the U.S. Army, which, prior to World War II, had under development tank, vehicular, and man-pack frequency-modulated radio transmitters and receivers. The British Army had also conducted a series of combined arms exercises with radios which, while largely ignored by the British Army, were assessed and analysed by others - such as the Germans (and the Finns, as we will see).

On the eve of World War II, all nations employed generally similar methods for military signaling. The messenger systems included foot, mounted, motorcycle, automobile, airplane, homing pigeon, and the messenger dog. Visual agencies included flags, lights, panels for signaling airplanes, and pyrotechnics. The electrical agencies embraced wire systems providing telephone and telegraph service, including the printing telegraph. Both radiotelephony and radiotelegraphy were in wide use, but radio-telephony had not as yet proved reliable and satisfactory for tactical military communication. The navies of the world entered World War II with highly developed radio communication systems, both telegraph and telephone, and with development under way of many electronic navigational aids. Blinker-light signaling was still used. The use of telephone systems and loud-speaking voice amplifiers on naval vessels had also come into common use. Air forces employed wire and radio communication to link up their bases and landing fields and had developed airborne long-range, medium-range, and short-range radio equipment for air-to-ground and air-to-air communication.

Suomen Maavoimat Signals and Radio

Please note that the content of this and subsequent Posts as far as OTL Finnish Army Radio and Signal’s equipment (and photos) is concerned is largely sourced from Antero Tanninen’s wonderfully detailed website, http://personal.inet.fi/koti/antero.tanninen/ - and more specifically, http://personal.inet.fi/koti/antero.tanninen/Radiotaulukko.htm - and is reused with Antero’s permission. If you’re interested in Finnish Radio equipment, Antero’s site goes into this subject in far greater detail than I’ve used – the content is primarily in Finnish but if you use Google Translate, you’ll get a pretty good idea of what it’s all about.

Suomen Maavoimat Signals units in the 1920’s

Within the Suomen Maavoimat, Signals units largely originated from the experience of the Finnish Jaeger movement within the German Army, as the Tsarist Russian Army allowed only infantry units for the military of the Grand Duchy of Finland, with no technical branches authorised. Consequently, there was no passing down of the Russian military expertise and experience with military communications, such as it was, into the Army of the nacent Finnish Republic on its formation. On independance from the Russian Empire, the ex-Tsarist Army Finnish officers largely came from the Infantry, Cavalry and Artillery branches only, while the Maavoimat’s technical branches were largely established by former Jaegers based on their German training and knowledge. Suomen Maavoimat Signals units were as a consequence primarily based on the experience and training of the Communications Section of the Finnish 27th Jaeger Battalion of the WWI German Army. The Jaegers returned to Finland in February 1918 and formed the Jaeger Kenttälennätinpataljoona (Field Telegraph Battalion) to meet Finnish Civil War needs. Initially, a significant part of their activities consisted of establish Field Telegraph stations (Kenttälennätinasemat) and running cables to connect field telephones.

WWI Field Telephone Team

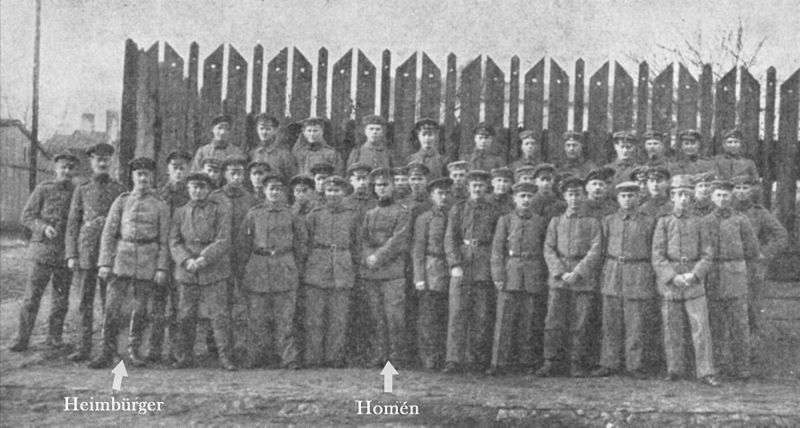

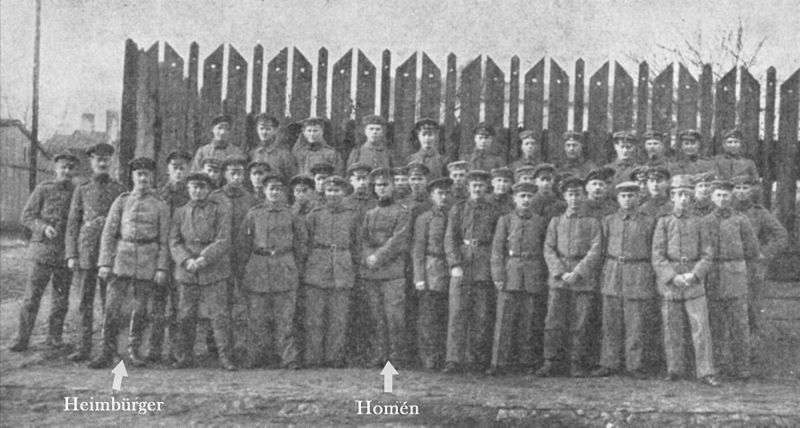

The Communication Section of the 27th Jaeger Battalion, commanded by Lars Homén and Eric Heimbürger (we will see more of Eric Heimbürger during the Winter War).

Eric Alexander Amandus Heimbürger (1888 - 1954):

Eric Alexander Amandus Heimbürger (Espoo, June 16, 1888 - February 1, 1954) was a Finnish Jaeger Colonel. His parents were the ownera of a manor, Nicolai Heimbürger and Therese von Jessen. Heimbürger completed matriculation at the Nya Svenska Läroverket in Helsinki in 1908 and then joined the Uusimaa Students' Association. He studied at the University Law Faculty in 1908-1909 and then at the University of Technology mechanical engineering department from 1909-1912, followed by a further year at the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology. Heimbürger joined one of the first groups of volunteers whose goal was to go to Germany for military training purposes and then fight for Finnish independance. He enrolled on 25 March 1915 and trained in northern Germany in the Lockstedter Lager training area. Initially he was placed in 1 Komppaniaan of the Prussian Jaeger Battalion 2. On 2 October 1917, he was transferred from the 1st Komppaniaan, together with 53 other men, to the battalion's Signals unit, where he served as the Finnish unit commander. He took part in a number of battles on the German Eastern Front, including Misse River, the Gulf of Riga and the Aa River. In the Spring of 1917, Heimbürger ran courses at Libau on Signals and was later moved to Commander of the Battalion’s Radio unit.

Heimbürger arrived in Finland (Vaasa), with the main group of Jaeger troops and was promoted to the rank of Senior Lieutenant on 25 February 1918. During the Civil War, ge was assigned commander of the 15th Jaeger Battalion 1st Company, after which he was transferred on 6 April 1918 to Headquarters as the Signals Commander. On 5 June 1918 he was moved to the General Staff and appointed Signals Force Commander. He worked as the supervisor of Signals courses, which in July 1918 were implemented in Helsinki. He taught Officer courses in 1920 and was a teacher on Signals at the Cadet School from 1919 to 1926. On 22 March 1920 he was ttransferred to military forces headquarters and placed in charge of Signals and on 8 December 1920 he was made Inspector of Technical Staff.

Heimbürger was the armed forces representative on the Telegraph Committee in 1919 and was a member of the Radio Committee in 1920 and also a member of the Committee responsible for planning the number and strength of bicycle troops in 1922. In 1923 he was a member of the Committee which drew up the proposals for the strength of the Telephone / Signals Troops and was Signals Troops honor court chairman in 1921. He was married in 1924, to Aune Emilia-Rekolan. Heimbürger was also posted to Lithuania in the 1924 period. In addition, he completed the General Staff course over 1927-1929. In April 1927 he was the Senior Staff teacher for Signals at the Military Academy. On 31 October 1927 he was appointed head of the Separate Signals Company (Kenttälennätin Komppanian, later the Independent Signals Battalion, where he was again Commanding Officer).

From 1 July 1933 he was appopinted to Army Corps headquarters, where he was Pioneer and Signals Commander. He also carryied out Chief of Staff duties in 1925. Over the Winter War, Heimbürger was Signals Commander for one of the Army Corps, then was appointed to Military Headquarters, during which time he made several trips abroad. He held this position until 1947, when he resigned from active service. He is buried in the Hietaniemi Cemetery, Helsinki.

The establishment of the Light Field Radio Department

In April 1918 a Field Radio Department was established and took over the radio stations in Helsinki and Suomenlinna from the Russian garrison troops. The unit also restored the former Santahamina fixed radio station which had been used by the Russian Baltic Fleet. The radio-type taken over from the Russians was a Telefunken with a 10W power level and a range which stretched from the Baltic Sea region to as far as Austria. Also during the Finnish Civil War, Suojeluskuntas Signals units were setup at Santahamina where radio stations were assembled. Their first commander was Jaeger Lieutenant Karl Edvard Nyström who in June 1918 formed the Field Radio Department (which later that year was changed to Field Radio Division).

Karl Edvard Nyström (born July 8 1894, Kokkola - March 1, 1964, Helsinki) was the child of copper smith Solomon Fredrik Nyström, and Edla Amanda Sandstrom. He received his early education at the Swedish School in Kokkola, then worked as a Telegrapher before travelling to Germany and joining the Finnish 27th Jaeger Battalion (2 Company). In December 1915 he was transferred to the Battalion’s Signals unit, going on to take part in battles on the Misse River , the Gulf of Riga and the Aa River over 1916, where he had his baptism of fire. In 1917 he organized special courses at Libau, before returning to Finland in December 1917 on the second trip of the S/S Equity, which carried many of the members of Jääkäripataljoona 27 from Germany back to Finland. On arrival in Finland, he traveled to Vaasa, where he trained Suojeluskuntas men from the the local and surrounding area in Signals work.

He participated in the civil war as Column Deputy Director for the seizing of Vaasa. After the takeover of Vaasa, he was assigned to the Vaasa Radio and Telegraph station on 7 February 1918. On 24 April 1918, he was transferred to Headquarters at Mikkeli. From Mikkeli, he was transferred to Viipuri as the station manager on 2 May 1918. In the post-Civil War period Nyström continued to serve as the Viipuri station manager, until 1 August 1918 when he was appointed Signals Company Commander, and then on 1 September 1921 temporary commander of the Signals Battalion. He was married in 1924 to Sigrid Maria Adelia Johanssonin and went on to complete further military educational courses in 1925. Nyström resigned from the army on 28 May 1926, having reached the rank of Major.

After leaving the Army, Nyström worked for Reko Ltd from 1927 to 1928. He later worked in a number of positions, including as a warehouse manager (from 1934 to 1935). During the Winter War, Nyström served in IV Corps Headquarters, later moving to Coastal Battalion 4 and then to a position as deputy CO of the Signals School. Following the Winter War, he served as an officer in the home office staff of the Army and was released from military service in 1942, after which he worked at a Machinery company and then as a businessman in Helsinki. He died in 1964 and was buried in Helsinki.

...To be continued......

The early origins of Radio

It’s hard to imagine what military communications were like before the radio, which in turn was derived from the electric telegraph – which in turn had its origins in the earlier optical semaphore systems. Such optical signal systems have been in existence in one form or another for centuries and were faster than the physical transfer of messages by horse-rider or runner. The distance thry could bridge was however limited by geography and weather; thus, in practical use, most optical semaphore systems used lines of relay stations to bridge longer distances. The first comprehensive non-electric optical semaphore telegraph system was invented by Claude Chappe for the French military in 1794. This system was visual and used semaphore, a flag-based alphabet, depended on a line of sight for communication and was widely adopted across Europe for both commercial and military use. They succeeded in covering France with a network of 556 stations stretching a total distance of 4,800 kilometres which was used for military and national communications until the 1850s.

Sweden was the second country in the world, after France, to introduce an optical sempahore network. The Swedish network was restricted to the archipelagoes of Stockholm, Gothenburg and Karlskrona. Like its French counterpart, it was mainly used for military purposes. In the UK, Lord George Murray, stimulated by reports of the Chappe semaphore, proposed a system of visual telegraphy to the British Admiralty in 1795. A Rev. Mr Gamble also proposed two alternative systems in the same year. The British Admiralty accepted Murray's system in September 1795, and the first system was the 15 site chain from London to Deal. Messages passed from London to Deal in about sixty seconds (a distance of 68 miles), and sixty-five sites were in use by 1808. Once it had proved its success, the optical semaphore system was imitated in many other countries, especially after it was used by Napoleon to coordinate his empire and army. In most of these countries, the postal authorities operated the semaphore lines.

In Canada, the first semaphore line in North America was in operation by 1800, running between the city of Halifax and the town of Annapolis in Nova Scotia, and across the Bay of Fundy to Saint John and Fredericton in New Brunswick. In 1801, the Danish post office installed a semaphore line across the Great Belt strait, Storebæltstelegrafen, between the islands Funen and Zealand with stations at Nyborg on Funen, on the small island Sprogø in the middle of the strait, and at Korsør on Zealand. It was in use until 1865. The Kingdom of Prussia began with a line 750 kilometres long between Berlin and Coblenz in 1833, and in Russia, Tsar Nicolas I inaugurated the line between Moscow and Warsaw (1200 km) in 1833; this needed 220 stations manned by 1320 operators. In the United States the first semaphore system was a 104-kilometre line connecting Martha's Vineyard with Boston, and its purpose was to transmit news about shipping. One of the principal hills in San Francisco, California is also named "Telegraph Hill", after the semaphore telegraph which was established there in 1849 to signal the arrival of ships into San Francisco Bay.

The semaphores were successful enough that Samuel Morse failed to sell the electrical telegraph to the French government. However, France finally committed to replace semaphores with electric telegraphs in 1846. The last stationary semaphore link in regular service was in Sweden, connecting an island to a mainland telegraph line. It finally went out of service in 1880. In general terms, the old sempahore systems were quickly superceded by electric telegraph systems after these became commercially viable. While today the electric telegraph is a virtually forgotten and outdated communication system that transmitted electric signals over wires from location to location that translated into a message, 130 years ago it was as revolutionary as the Internet is today and was the direct ancestor of both the telephone and the radio – two devices that revolutionsed military communications.

While the electric telegraph itself had its origins some 250 years ago (in 1746 the French scientist, Abbé Jean-Antoine Nollet, gathered about two hundred monks into a circle about a mile (1.6 km) in circumference, with pieces of iron wire connecting them. He then discharged a battery of Leyden jars through the human chain and observed that each man reacted at substantially the same time to the electric shock, showing that the speed of electricity's propagation was very high) and there were many intermediate steps along the way, it only became a commercially practical means of communication in the 1840’s. Knowledge and commercial application of the telegraph percolated quickly throughout North America and Europe, and development of the technology was rapid. In the UK, the electric telegraph entered commercial use on the Great Western Railway over the 13 miles (21 km) from Paddington station to West Drayton on 9 April 1839 while in the USA, the first commercial telegraph line in the United States ran along a railroad right-of-way between Lancaster and Harrisburg, Pennsylvania in 1845. Dispatching trains by telegraph started in the USA in 1851, the same year Western Union began business. On 24 October 1861, the first transcontinental telegraph system was established. Spanning North America, an existing network in the eastern United States was connected to the small network in California by a link between Omaha and Carson City via Salt Lake City.

Experiments with a transatlantic telegraph cable began in 1857 and 1858, but these failed after only a few days or weeks – but by 1866 a working transatlantic telegraph cable was successfully in operation. Within 29 years of its first commercial introduction, the telegraph network connected every continent in the world except Antarctica, making instant global communication possible for the first time. The telegraph thus liberated information transfer from transportation.

World Map of Undersea Cables from 1901

Early military utilization of the Electric Telegraph

Military organizations were quick to see the utility of the electric telegraph, with the first such recorded use in war being during the Crimean War between Russia, Britain and France. A combined British and French force landed in the Crimea and began a long-term siege of the city and naval base of Sebastopol. Britian, the home of the “Industrial Revolution” put its industrial skills to use in warfare through a series of different applications of engineering knowhow - the railway contractor Morton Peto and his partner Thomas Brassey created a Railway Construction Corps from their own army of labourers and built a full-scale railway from the base port at Balaklava to the front line. The mining industry in Leeds contributed two steam engines to work it. Joseph Paxton, architect of the Crystal Palace, organised an Army Works Corps to erect a township of wooden huts to protect the troops in the bitter winter. I K Brunel, the railway engineer, designed and had built a huge hospital from prefabricated components. William Fairbairn, the ironmaster and shipbuilder, constructed a pair of floating workshops to undertake all manner of repair and maintenance tasks for the besieging army.

The telegraph companies and their suppliers joined in with this war euphoria. In late 1854, the government in London created a military Telegraph Detachment for the Army commanded by an officer of the Royal Engineers. It was to comprise twenty-five men from the Royal Corps of Sappers & Miners, a cadre of which were trained by the Electric Telegraph Company to construct and work the first Field Electric Telegraph, as it was called.

The Electric Telegraph Company’s War Wagon 1854: The outfit for the first war telegraph, usually hauled by three pair of horses, even had a gutta percha boat inverted on the top. The sketch shows a heavy cavalry trooper riding postillion rather than a sapper.

The Telegraph Detachment’s lines allowed Lord Raglan (the C-in-C) to communicate within a few minutes with his generals at any time and the Telegraph Detachment eventually possessed eight Field Electric Telegraph stations, 24 miles of line around Sebastopol, connecting the Headquarters, Kazach, the Monastery, the Engineer Park, the Right Attack, the Light Division, Kadikoi and Balaklava.. A temporary 310 mile long submarine cable also connected British headquarters in Balaklava to Varna in Turkish Bulgaria. This connected to the European circuits via a French Army-built land line to existing Austrian circuits at Bucharest, hence to London and Paris in autumn 1855. A cable for the British government was also run from Varna direct to Constantinople, the Turkish capital, where another land circuit existed to Vienna and the European capitals.

After the Crimea, the British Army rapidly adopted the electrical telegraph for internal communication in its fortresses at Malta and then at Gibraltar, then elsewhere in the late 1850s. Three years after the Crimean War, in the Indian Mutiny, the newly established telegraph, which was controlled by the British, was a deciding factor. The Royal Engineers also despatched telegraph detachments, similar to those assembled for the Crimea, with the expeditions to China in 1859 and Hazara in Afghanistan during 1868. The French Empire had learned from observing their allies in the British Army during the Crimea war and for their brief and bloody campaign in northern Italy against Austria in 1859 they organised a “service télégraphiques” which laid 400 kilometres of line and created thirty-five telegraph stations along the advance to keep the army in touch with metropolitan France. It was claimed that at the decisive battle of Solferino on June 24, 1859 “the movement of the whole army was known and regulated like clockwork” by telegraph.

Between October 1859 and April 1860 Spain was at war with Morocco, with an army under General Leopoldo O’Donnell based from the Spanish enclave of Ceuta. The Royal government in Madrid commissioned a war telegraph, the largest element of which was a 25 mile underwater cable linking the mainland at Tarifa, near Algeciras, across the Mediterranean to Ceuta on the Moroccan coast. Use was also made of Field Telegraph detachments.

(please note that most of the above military telegraph information was sourced from http://distantwriting.co.uk/default.aspx, “A History of the Telegraph Companies in Britain between 1838 and 1868 by Robert Stevens – the site has a vast amount of really interested information on the Electric Telegraph in Britain)

In the American Civil War (1861–65), wide use was made of the electric telegraph. In addition to its employment in spanning long distances under the civilian-manned military telegraph organization, a mobile field service was provided in the Union army by wagon trains equipped with insulated wire and lightweight poles for the rapid laying of telegraph lines. Immediately before and during the Civil War visual signaling also received added impetus through the development of a system applying the Morse code of dots and dashes that spelled out messages with flags by day and lights or torches by night. Another development for light signaling placed a movable shutter, controlled by a key, in front of a strong light. An operator, opening and closing the shutter, could produce short and long flashes to spell out messages in Morse code.

Simultaneously, the Prussian and French armies also organized mobile telegraph trains. During the short, decisive Prussian campaign against Austria in 1866, field telegraphs enabled Count Helmuth von Moltke, the Prussian commander, to exercise command over his distant armies. Soon afterward the British organized their first permanent field telegraph units in the Royal Engineers. Until 1877, all rapid long-distance communication depended upon the telegraph. That year, a rival technology developed that would again change the face of communication -- the telephone. The invention of the telephone in 1876 was not followed immediately by its adoption and adaptation for military use. This was probably due to the fact that the compelling stimulation of war was not present and to the fact that the development of reliable long-distance telephone communication was not achieved for many years. The telephone was used by the U.S. Army in the Spanish-American War, by the British in the South African (Boer) War, and by the Japanese in the Russo-Japanese War. This military use was not extensive, and it made little material contribution to the development of voice telephony. Before the outbreak of World War I, military adaptation of the telephone did take place, but its period of growth had not yet arrived.

Near the close of the 19th century, a new means of military signal communication made its appearance—the wireless telegraph, or radio. The major powers throughout the world were quick to see the wonderful possibilities for military and naval signaling. Development was rapid and continuous, and, by 1914, it was adopted and in extensive use by all the armies and navies of the world. It soon became apparent that wireless telegraphy was not an unmixed blessing to armies and navies, because it lacked secrecy and messages could be heard by the enemy as well as by friendly forces. This led to the development of extensive and complicated codes and ciphers as necessary adjuncts to military signaling. The struggle between the cryptographer and the cryptanalyst expanded greatly with the adoption of radio and continued to be a major factor affecting its military use.

Military usage and evolution of telephone and radios in WW1

The onset of World War I found the opposing armies equipped to a varying degree with modern means of signal communication but with little appreciation of the enormous load that signal systems must carry to maintain control of the huge forces that were set in motion. The organization and efficiency of the armies varied greatly. At one end of the scale was Great Britain, with a small but highly developed signal service; and at the other end stood Russia, with a signal service inferior to that of the Union Army at the close of the American Civil War. The fact that commanders could not control, coordinate, and direct huge modern armies without efficient signal communication quickly became apparent to both the Allies and the Central Powers. The Germans, despite years of concentration on the Schlieffen Plan, failed to provide adequately for communication between higher headquarters and the rapidly marching armies of the right wing driving through Belgium and northern France. This resulted in a lack of coordination between these armies, which caused a miscarriage of the plan, a forced halt in the German advance, and the subsequent withdrawal north of the Marne. On the Allied side, the debacle of the Russian forces in East Prussia — a crushing defeat of the Starist Russian Army at the hands of General Paul von Hindenburg in the Battle of Tannenberg — was in large part due to an almost total lack of effective signals communication by the Russian forces.

As the war progressed there was a growing appreciation of the need for improved electrical communications of much greater capacity for the larger units and of the need within regiments for electrical communications, which had heretofore been regarded as unessential and impractical. Field telephones and switchboards were soon developed, and those already in existence were improved. An intricate system of telephone lines involving thousands of miles of wire soon appeared on each side. Pole lines with many crossarms and circuits came into being in the rear of the opposing armies, and buried cables and wires were laid in the elaborate trench systems leading to the forwardmost outposts. The main arteries running from the rear to the forward trenches were crossed by lateral cable routes roughly parallel to the front. Thus, there grew an immense gridwork of deep buried cables, particularly on the German side and in the British sectors of the Allied side, with underground junction boxes and test points every few hundred yards. The French used deep buried cable to some extent but generally preferred to string their telephone lines on wooden supports set against the walls of deep open trenches. Thus electrical communication in the form of the telephone and telegraph gradually extended to the smaller units until front-line platoons were frequently kept in touch with their company headquarters through these mediums.

Radio Equipment in a WW1 Dugout

Marconi Trench Set

Marconi Motorcycle Set

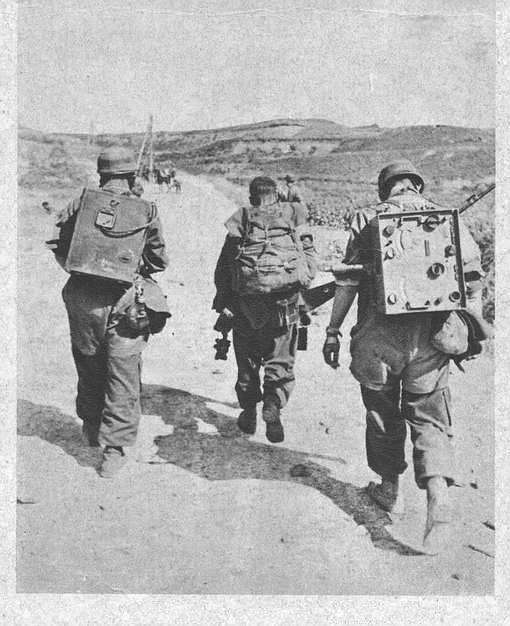

Marconi Pack Set

Marconi Wireless Pack Set

Marconi Horse Set

Despite efforts to protect the wire lines, they were frequently cut at critical times as the result of the intense artillery fire. This led all the belligerents to develop and use radio (wireless) as an alternate means of communication. Prewar radio sets were too heavy and bulky to be taken into the trenches, and they also required large and highly visible aerials. Radio engineers of the belligerent nations soon developed smaller and more portable sets powered by storage batteries and using low, inconspicuous aerials. Although radio equipment came to be issued to the headquarters of all units, including battalions, the ease of enemy interception, the requirements for cryptographing or encoding messages, and the inherent unreliability of these early systems caused them to be regarded as strictly auxiliary to the wire system and reserved for emergency use when the wire lines were cut. Visual signaling returned to the battlefield in World War I with the use of electric signal lamps. Pyrotechnics, rockets, Very pistols, and flares had a wide use for transmitting prearranged signals. Messenger service came to be highly developed, and motorcycle, bicycle, and automobile messenger service was employed. Homing pigeons were used extensively as one-way messengers from front to rear and acquitted themselves extremely well. Dogs were also used as messengers and, in the German army, reached a high degree of efficiency.

A new element in warfare, the airplane, introduced in World War I, immediately posed a problem in communication. During most of the war, communication between ground and air was difficult and elementary. To make his reports the pilot had to land or drop messages, and he received instructions while in the air from strips of white and black cloth called “panels” laid out in an open field according to prearranged designs. Extensive efforts were made to use radiotelegraph and radiotelephone between the airplanes and ground headquarters. The closing stages of the war saw many planes equipped with radio, but the service was never entirely satisfactory or reliable and had little influence on military operations. During World War I however, wireless telegraph (radio) communication was employed extensively by the navies of the world and had a major influence on the character of naval warfare. High-powered shore and ship stations made wireless communication over long distances possible. One of the war lessons learned by most of the major nations was the compelling need for scientific research and development of radio equipment and techniques for military purposes.

An over-view of Inter-war Developments.

Although the amount of funds devoted to military development during the period from World War I to World War II was relatively small, the modest expenditures served to establish a bond between industry, science, and the armed forces of the major nations. Of great importance in postwar radio communication was the pioneering by amateurs and by industry and science in the use of very high frequencies. These developments opened up to the armed services the possibilities of portable short-range equipment for mobile and portable tactical use by armies, navies, and air forces. Military work in these fields was carried out actively in Germany, Great Britain and the United States among others. Of the major powers, Germany as early as 1938 had completed the design and manufacture of a complete line of portable and mobile radio equipment for its army and air force.

Between World Wars I and II the printing telegraph, commonly known as the teleprinter or teletypewriter machine, came into civilian use and was incorporated in military wire-communication systems, but military networks were not extensive. Before World War II, military radioteleprinter circuits were nonexistent. Another major communication advance that had its origin and early growth during the period between World Wars I and II was frequency-modulated (FM) radio. Developed during the late 1920s and early 1930s by Edwin H. Armstrong, an inventor and a major in the U.S. Army Signal Corps during World War I, this new method of modulation offered heretofore unattainable reduction of the effect of ignition and other noises encountered in radios used in vehicles. It was first adapted for military use by the U.S. Army, which, prior to World War II, had under development tank, vehicular, and man-pack frequency-modulated radio transmitters and receivers. The British Army had also conducted a series of combined arms exercises with radios which, while largely ignored by the British Army, were assessed and analysed by others - such as the Germans (and the Finns, as we will see).

On the eve of World War II, all nations employed generally similar methods for military signaling. The messenger systems included foot, mounted, motorcycle, automobile, airplane, homing pigeon, and the messenger dog. Visual agencies included flags, lights, panels for signaling airplanes, and pyrotechnics. The electrical agencies embraced wire systems providing telephone and telegraph service, including the printing telegraph. Both radiotelephony and radiotelegraphy were in wide use, but radio-telephony had not as yet proved reliable and satisfactory for tactical military communication. The navies of the world entered World War II with highly developed radio communication systems, both telegraph and telephone, and with development under way of many electronic navigational aids. Blinker-light signaling was still used. The use of telephone systems and loud-speaking voice amplifiers on naval vessels had also come into common use. Air forces employed wire and radio communication to link up their bases and landing fields and had developed airborne long-range, medium-range, and short-range radio equipment for air-to-ground and air-to-air communication.

Suomen Maavoimat Signals and Radio

Please note that the content of this and subsequent Posts as far as OTL Finnish Army Radio and Signal’s equipment (and photos) is concerned is largely sourced from Antero Tanninen’s wonderfully detailed website, http://personal.inet.fi/koti/antero.tanninen/ - and more specifically, http://personal.inet.fi/koti/antero.tanninen/Radiotaulukko.htm - and is reused with Antero’s permission. If you’re interested in Finnish Radio equipment, Antero’s site goes into this subject in far greater detail than I’ve used – the content is primarily in Finnish but if you use Google Translate, you’ll get a pretty good idea of what it’s all about.

Suomen Maavoimat Signals units in the 1920’s

Within the Suomen Maavoimat, Signals units largely originated from the experience of the Finnish Jaeger movement within the German Army, as the Tsarist Russian Army allowed only infantry units for the military of the Grand Duchy of Finland, with no technical branches authorised. Consequently, there was no passing down of the Russian military expertise and experience with military communications, such as it was, into the Army of the nacent Finnish Republic on its formation. On independance from the Russian Empire, the ex-Tsarist Army Finnish officers largely came from the Infantry, Cavalry and Artillery branches only, while the Maavoimat’s technical branches were largely established by former Jaegers based on their German training and knowledge. Suomen Maavoimat Signals units were as a consequence primarily based on the experience and training of the Communications Section of the Finnish 27th Jaeger Battalion of the WWI German Army. The Jaegers returned to Finland in February 1918 and formed the Jaeger Kenttälennätinpataljoona (Field Telegraph Battalion) to meet Finnish Civil War needs. Initially, a significant part of their activities consisted of establish Field Telegraph stations (Kenttälennätinasemat) and running cables to connect field telephones.

WWI Field Telephone Team

The Communication Section of the 27th Jaeger Battalion, commanded by Lars Homén and Eric Heimbürger (we will see more of Eric Heimbürger during the Winter War).

Eric Alexander Amandus Heimbürger (1888 - 1954):

Eric Alexander Amandus Heimbürger (Espoo, June 16, 1888 - February 1, 1954) was a Finnish Jaeger Colonel. His parents were the ownera of a manor, Nicolai Heimbürger and Therese von Jessen. Heimbürger completed matriculation at the Nya Svenska Läroverket in Helsinki in 1908 and then joined the Uusimaa Students' Association. He studied at the University Law Faculty in 1908-1909 and then at the University of Technology mechanical engineering department from 1909-1912, followed by a further year at the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology. Heimbürger joined one of the first groups of volunteers whose goal was to go to Germany for military training purposes and then fight for Finnish independance. He enrolled on 25 March 1915 and trained in northern Germany in the Lockstedter Lager training area. Initially he was placed in 1 Komppaniaan of the Prussian Jaeger Battalion 2. On 2 October 1917, he was transferred from the 1st Komppaniaan, together with 53 other men, to the battalion's Signals unit, where he served as the Finnish unit commander. He took part in a number of battles on the German Eastern Front, including Misse River, the Gulf of Riga and the Aa River. In the Spring of 1917, Heimbürger ran courses at Libau on Signals and was later moved to Commander of the Battalion’s Radio unit.

Heimbürger arrived in Finland (Vaasa), with the main group of Jaeger troops and was promoted to the rank of Senior Lieutenant on 25 February 1918. During the Civil War, ge was assigned commander of the 15th Jaeger Battalion 1st Company, after which he was transferred on 6 April 1918 to Headquarters as the Signals Commander. On 5 June 1918 he was moved to the General Staff and appointed Signals Force Commander. He worked as the supervisor of Signals courses, which in July 1918 were implemented in Helsinki. He taught Officer courses in 1920 and was a teacher on Signals at the Cadet School from 1919 to 1926. On 22 March 1920 he was ttransferred to military forces headquarters and placed in charge of Signals and on 8 December 1920 he was made Inspector of Technical Staff.

Heimbürger was the armed forces representative on the Telegraph Committee in 1919 and was a member of the Radio Committee in 1920 and also a member of the Committee responsible for planning the number and strength of bicycle troops in 1922. In 1923 he was a member of the Committee which drew up the proposals for the strength of the Telephone / Signals Troops and was Signals Troops honor court chairman in 1921. He was married in 1924, to Aune Emilia-Rekolan. Heimbürger was also posted to Lithuania in the 1924 period. In addition, he completed the General Staff course over 1927-1929. In April 1927 he was the Senior Staff teacher for Signals at the Military Academy. On 31 October 1927 he was appointed head of the Separate Signals Company (Kenttälennätin Komppanian, later the Independent Signals Battalion, where he was again Commanding Officer).

From 1 July 1933 he was appopinted to Army Corps headquarters, where he was Pioneer and Signals Commander. He also carryied out Chief of Staff duties in 1925. Over the Winter War, Heimbürger was Signals Commander for one of the Army Corps, then was appointed to Military Headquarters, during which time he made several trips abroad. He held this position until 1947, when he resigned from active service. He is buried in the Hietaniemi Cemetery, Helsinki.

The establishment of the Light Field Radio Department

In April 1918 a Field Radio Department was established and took over the radio stations in Helsinki and Suomenlinna from the Russian garrison troops. The unit also restored the former Santahamina fixed radio station which had been used by the Russian Baltic Fleet. The radio-type taken over from the Russians was a Telefunken with a 10W power level and a range which stretched from the Baltic Sea region to as far as Austria. Also during the Finnish Civil War, Suojeluskuntas Signals units were setup at Santahamina where radio stations were assembled. Their first commander was Jaeger Lieutenant Karl Edvard Nyström who in June 1918 formed the Field Radio Department (which later that year was changed to Field Radio Division).

Karl Edvard Nyström (born July 8 1894, Kokkola - March 1, 1964, Helsinki) was the child of copper smith Solomon Fredrik Nyström, and Edla Amanda Sandstrom. He received his early education at the Swedish School in Kokkola, then worked as a Telegrapher before travelling to Germany and joining the Finnish 27th Jaeger Battalion (2 Company). In December 1915 he was transferred to the Battalion’s Signals unit, going on to take part in battles on the Misse River , the Gulf of Riga and the Aa River over 1916, where he had his baptism of fire. In 1917 he organized special courses at Libau, before returning to Finland in December 1917 on the second trip of the S/S Equity, which carried many of the members of Jääkäripataljoona 27 from Germany back to Finland. On arrival in Finland, he traveled to Vaasa, where he trained Suojeluskuntas men from the the local and surrounding area in Signals work.

He participated in the civil war as Column Deputy Director for the seizing of Vaasa. After the takeover of Vaasa, he was assigned to the Vaasa Radio and Telegraph station on 7 February 1918. On 24 April 1918, he was transferred to Headquarters at Mikkeli. From Mikkeli, he was transferred to Viipuri as the station manager on 2 May 1918. In the post-Civil War period Nyström continued to serve as the Viipuri station manager, until 1 August 1918 when he was appointed Signals Company Commander, and then on 1 September 1921 temporary commander of the Signals Battalion. He was married in 1924 to Sigrid Maria Adelia Johanssonin and went on to complete further military educational courses in 1925. Nyström resigned from the army on 28 May 1926, having reached the rank of Major.

After leaving the Army, Nyström worked for Reko Ltd from 1927 to 1928. He later worked in a number of positions, including as a warehouse manager (from 1934 to 1935). During the Winter War, Nyström served in IV Corps Headquarters, later moving to Coastal Battalion 4 and then to a position as deputy CO of the Signals School. Following the Winter War, he served as an officer in the home office staff of the Army and was released from military service in 1942, after which he worked at a Machinery company and then as a businessman in Helsinki. He died in 1964 and was buried in Helsinki.

...To be continued......

A quick look at the overall state of Maavoimat Signals in late 1939

Before we go on to look at Signals equipment and Signals units, primarily of the Maavoimat, we'll first take a quick look at the overall state of Maavoimat Signals in late 1939

The overall state of Maavoimat Signals in late 1939

To understand just how effective the Suomen Maavoimat’s communication systems were in 1939, and the advantage that they gave to the Finnish military in battle, it is necessary to have a basic understanding of the state of military communications at the time. Today, it is almost impossible to understand what it was like to operate without an effective means of rapid communication. But even today, the Fog of War can descend on a battlefield, rendering headquarters out of touch with subordinate units and unable to make timely decisions based on up to the minute information. The practical experience of the fog of war is most easily demonstrated in the tactical battlespace. It may include military commanders' incomplete or inaccurate intelligence about the enemy's numbers, disposition, capabilities, and intent, regarding features of the battlefield, and incomplete knowledge of the state of their own forces. Fog of war is caused by the limits of reconnaissance, by the enemy's feints and disinformation, by delays in receiving intelligence and difficulties passing orders, and by the difficult task of forming a cogent picture from a very large (or very small) amount of diverse data. The Maavoimat was very much aware of this, as was every military in theory. The difference however, was that the Maavoimat had studied and theorized the problem, then actively sought ways to lift the fog for their own forces, and thicken it for the enemy.

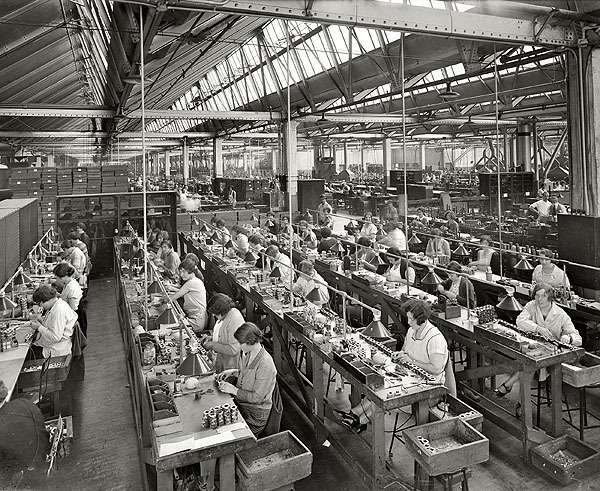

In late 1939, the primary combat formation of the Suoment Maavoimat was the Regimental Battle Group, an over-sized Brigade formation which incorporated infantry, artillery, support units, the use of close air support and, where available and necessary for specific operations, armoured formations and other supporting units. The development of the highly flexible combined arms Regimental Battle Group by the Suomen Maavoimat had been an evolutionary process through the 1930’s, initially based on experimentation in exercises and then at the last incorporating a large dose of practical experience from the involvement of the Finnish Volunteers in the Spanish Civil War. Both the exercises and the experiences in the crucible of Spain had graphically illustrated both the advantages and necessities of real-time communication within units at all levels. With a high degree of emphasis on mobility, the tactical offensive and rapid attacks and withdrawals, all of which required a high degree of coordination, the Suomen Maavoimat had from 1932 on placed a remarkable and ongoing emphasis on the development of effective communications systems.

Within the Suomen Maavoimat, portable radio sets were provided as far down in the military echelons as the infantry company – and in many cases down to the infantry platoon. In every tank there was at least one radio and in some command tanks as many as three – as there were with artillery batteries. High-powered mobile radio sets equipped Headquarters Units at Army Group, Divisional, Regimental Battle Group and Battalion level. With these sets radio communications could be conducted at distances of more than 100 miles (160 kilometres) with vehicles in normal motion on the road. Multiconductor cables were provided for wire communications; they could be reeled out rapidly and as many as four conversations could take place on them simultaneously through the use of carrier telephony. The Germans had been the first to use this type of military long-range cable, and their example was followed promptly by the Finns, who kept in close contact with German telephone and radio equipment developments. Major telephone switchboards of much greater capacity were needed and had been developed, manufactured and issued for use at all tactical headquarters to satisfy the need for the greatly increased number of telephone channels required to coordinate the movements of highly mobile field units.

A Maavoimat ParaJaeger Signals Team on a route march, Lapland, Summer 1939. Similar 3-man Radio Teams were a part of every Infantry unit down to the Company and at times the Platoon level and would form the backbone of the Maavoimat’s front-line communications network through the Winter War, considerably enhancing the combat effectiveness of Finland’s soldiers.

On the outbreak of the Winter War, the Suomen Maavoimat also possessed a highly capable Signals Intelligence unit which we will cover in detail when we review the Maavoimat’s major units in a later Post. Seperately, we will also look at a further initiative of the Signals Intelligence which would have a major impact on the air war in the later stages of the Winter War. Likewise, the Ilmavoimat possessed a highly capable photographic reconnaissance unit, while the Artillery and Air Support Observer Aircraft provided a highly effective coverage of front-line areas and the immediate enemy rear. In addition, there were also the Maavoimat’s highly effective Deep Recconnaisance Teams who operated far behind the enemy’s front lines, providing strategic information to Military Headquarters to great effect and communicating using the outstanding (and top-secret) Finnish-designed and developed “Kynnel” Radio.

The Maavoimat to a large extent emphasized small-unit fighting – with the exception of the Karelian Isthmus, the forest, lake and swamp terrain of much of Finland lent itself to small-unit maneouvering and fighting with combined arms teams operating in small semi-autonomous groups but with the ability to quickly regroup and work together to fight major engagements. The tactics developed by the Maavoimat in the late 1930’s resembled what we would now call “swarming” – combat teams cooperating closely through simple decision rules, a shared situational awareness and the ability to communicate planned actions and call in artillery and with close air support virtually on demand. The essence of the strategy was to create psychological shock and resultant disorganization in enemy forces through the employment of surprise, speed, and localised superiority in firepower. Tested by the Finnish Volunteers during the Spanish Civil War over the period 1937-38, the tactic proved to be a formidable combination of land and air action. The essence of the tehcnique was the use of mobility, shock, and locally concentrated firepower in skillfully coordinated attacks to paralyze an adversary’s capacity to coordinate his own defenses, rather than attempting to physically overcome them, and then to exploit this paralysis.

During the Spanish Civil War, the Ilmavoimat’s leading theorist and commander of the Finnish Volunteer air force units, Richard “Zimbo” Lorentz, conceptualized the combat process and applied this to the logic of military operations, both tactical and strategic. As Lorentz stated, “In order to win, we should operate at a faster tempo or rhythm than our adversaries - or, better yet, get inside our adversary's “Havaita-Punnita-Ratkaisu-Taistelu (Perceive-Weigh in one’s mind-Solution-Combat Action) loop. ... Such activity will make us appear unpredictable and thereby generate confusion and disorder among our adversaries--since our adversaries will be unable to adapt to the faster rhythm of combat they are competing against. ….. The key is to obscure our intentions and make them unpredictable to our opponent while we simultaneously clarify his intentions. That is, we operate at a faster tempo to generate rapidly changing conditions that inhibit our opponent from adapting or reacting to those changes while suppressing or destroying his awareness. Thus, a hodgepodge of confusion and disorder occurs to cause him to over- or under-react to conditions or activities that appear to be uncertain, ambiguous, or incomprehensible. The proper mindset is to work with the chaos of the battlefield, allow this to become part of our thought system, and to use it to our advantage by simply creating more chaos and confusion for the opponent. We will funnel the inevitable chaos of the battlefield in the direction of the enemy and use this to our advantage.”

The primary observation made by Lorentz was that at both a strategic and tactical level it was important to think, decide and act faster than the enemy could think and act – i.e., “get inside our adversary's “Havaita-Punnita-Ratkaisu-Taistelu” loop and thereby producing opportunities for the enemy to react inappropriately. The approach favored agility over raw power and as such, was a further step in the development of the Maavoimat’s combat doctrine and again, emphasized excellent communications as a co-requisite of the tactics. The pervasiveness of portable radios at all levels together with an excellent field telephone network within the Maavoimat on the outbreak of the Winter War combined with superb air-based strategic and tactical reconnaissance (reconnaissance photos were generally available for analysis within an hour of the aircraft landing and the results available to front-line units shortly thereafter. The Ilmavoimat / Maavoimat aerial mapping service for example was so good that it usually took on average of only 48 hours from taking the picture to distributing printed maps to the troops) made this possible.

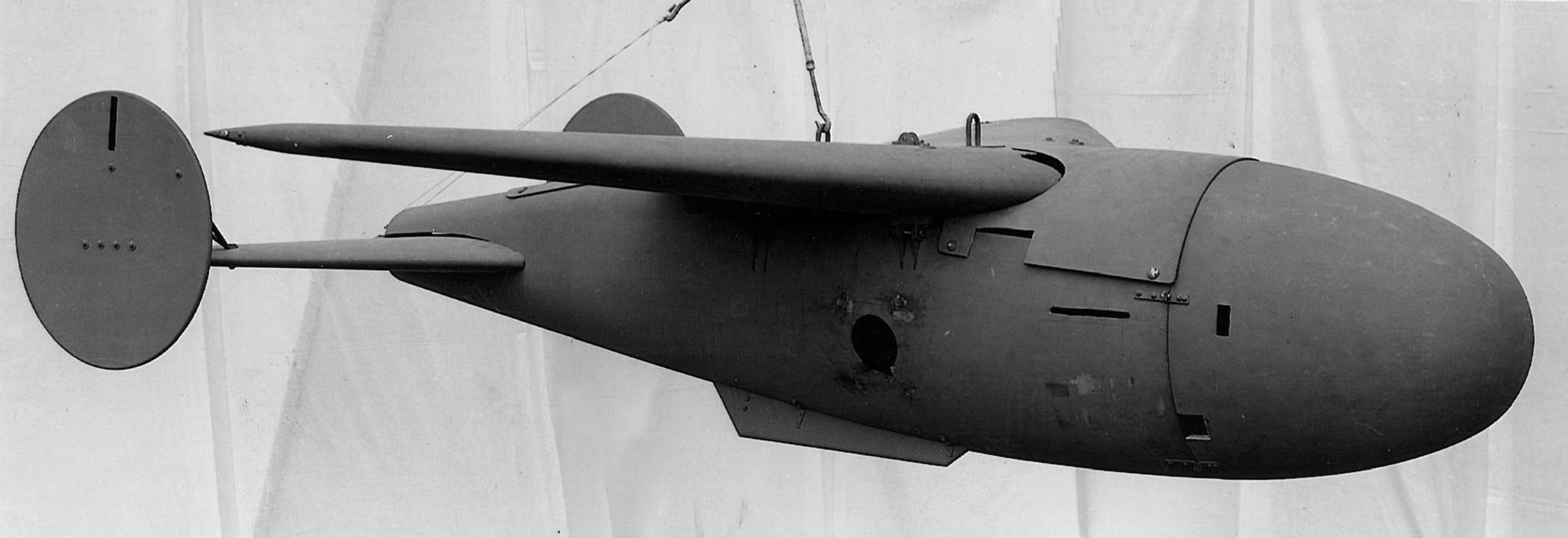

The same doctrine of creating psychological shock and resultant disorganization in the enemy forces that drove the improvement and pervasiveness of the Maavoimat’s communications network would go on to drive the formation of a range of what we now call “special forces” units within the Maavoimat, some focused on reconnaissance and some on attacks against the enemy rear – with one specific mission focus being the identification and annihilation of headquarters units, either through identification and elimination by close air support or artillery, or via direct action. The cutting of the enemy’s communications and logistical supply lines was another important mission of these units. Other (far smaller) units focused on misdirection and misinformation. “Mannerheims Wizards: The Finnish Genius for Deception 1939-1945” (Otava, 1975), describes Finnish military deception activities through WW2. The Finnish military enlisted the aid of an array of Finnish artists, film-makers, stage designers from theatres and as well as an array of scientists and oddballs to conceal, confuse and mislead. For example, to mislead Soviet bombers at night, an entire “false Helsinki” was created. Near the frontlines, dummy artillery positions were built using painted wooden mockups. Real defensive positions of all types were carefully concealed while “fake” defensive positions were created. “Fake” airfields complete with mockup aircraft were created to draw Soviet air force attacks and special attention was also paid to individual vehicle and team-manned weapons concealment as well as to individual camflauge (the well-known whiter smocks the Finnish soldiers wore during the Winter of 1939-40 were only one aspect of this concealment strategy).

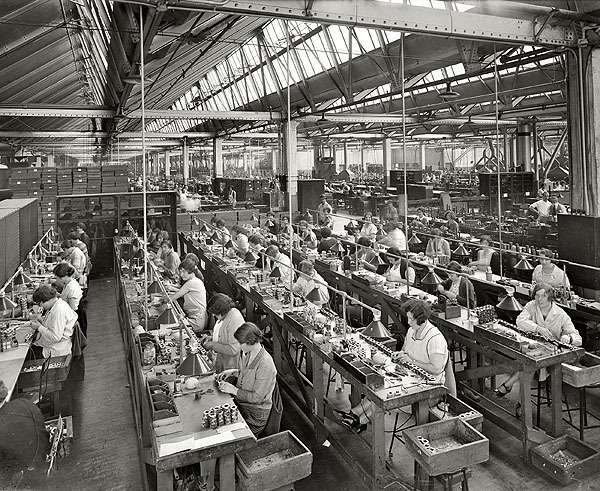

Most films at this time were made under cover, but so good were the film crews that they could make sets look very realistic. With lighting and paint and mock ups of buildings and streets many an audience watching a film would have never guessed it had been made entirely under cover, the main reason of making films this way was the weather was not reliable enough to make them outside on location, and film equipment at that time was not so robust as now. The film men from the Finnish film industry became the backbone of this unit, where they mass produced dummy aircraft and equipment to be used on decoy airfield sites as well as items such as dummy tanks and artillery and even complete Infantry Divisions.

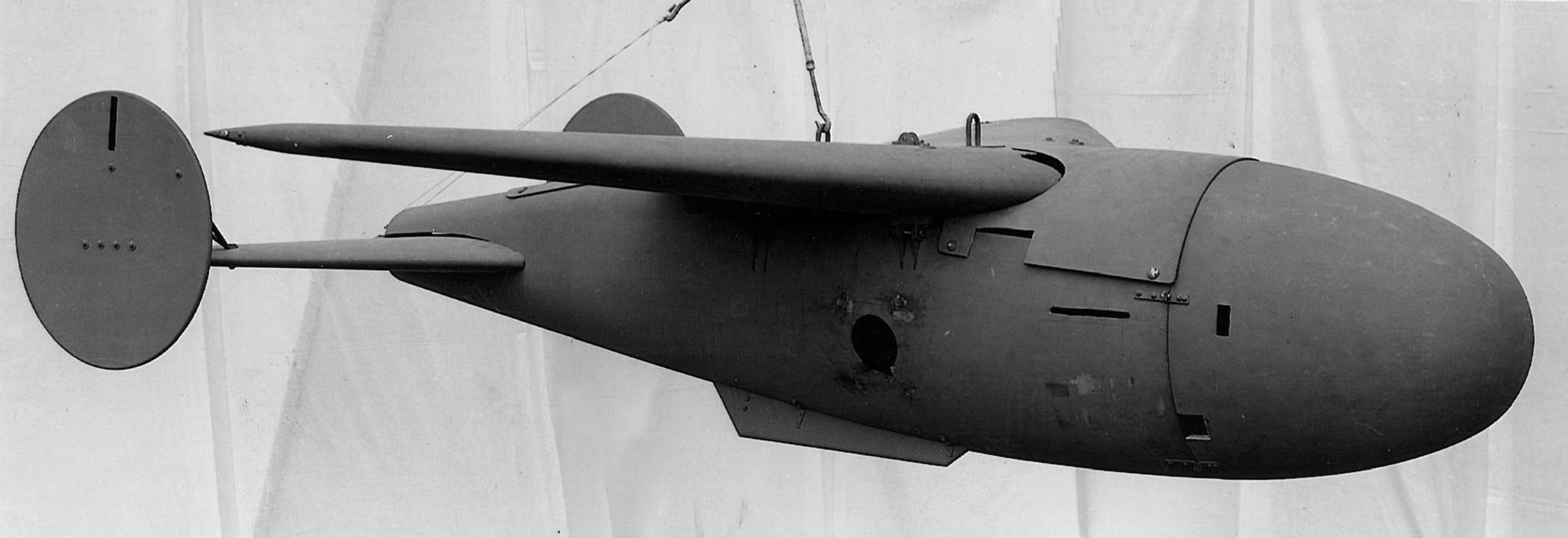

Dummy Ilmavoimat Hurricane built for a fake airfield: Summer 1940 (the dummy aircraft was constructed from wood, canvas and paint and was designed to look completely realistic from the air). The Soviet Air Force wasted some 80% of their attacks on Ilmavoimat airfields on such dummy targets.

On the front line, the Maavoimat placed a strong emphasis on the use of trained snipers to eliminate the enemy command structure – and as we will see when we review the Maavoimat’s structure, all infantry units down to the Platoon included specialist sniper teams. But that’s an aside to the main thrust of this Post, which has been to illustrate the Communications equipment used by the Maavoimat in the Winter War, and the pervasiveness of the Maavoimat’s radio and telephone communications network.