“The people will govern through a properly-constituted government but never through the trade union movement, irrespective of the dreams of some.”

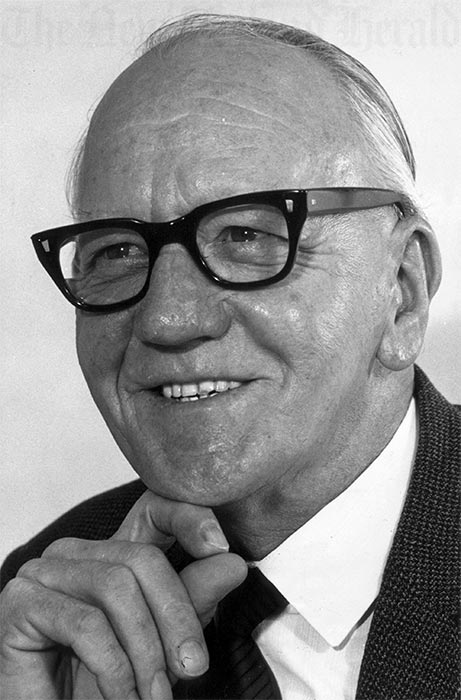

Norman Douglas (1968-1971)

“Big Norm” Douglas was not, of course, the biggest Norman in the Third Labour Government, but had been given the nickname according to the law of comedic inversion – Norman Kirk, the jovially enormous man who at six foot two and fourteen stone bestrode the benches like a colossus, was named “Little Norm.” Big Norm wasn’t a particularly small man, but his pinned-up left sleeve (he’d lost his arm duck-shooting at age sixteen) and the rather overshadowing presence of Little Norm meant the monikers stuck once both were seen standing next to each other in caucus.

After the 1962 washout he wasn't the frontrunner for the leadership either; Douglas had broken with the Labour frontbench over the Lee Affair in 1940 and joined Lee’s briefly extant Democratic Labour Party in 1941, just in time to get thrashed. After spending the 1940s in the wilderness (if you can call it that, given how much happier he was agitating on behalf of the workers), Lee was further estranged by the events surrounding the abortive waterfronters’ strike of 1951, when Nordmeyer had stated the Labour Party’s opposition to the “counterproductive” motion by the trade union movement and deregistered the Carpenters’ Union, and never mind the sop he’d made to the movement by expressing “Labour’s continued principled support”.

As a big wheel within the trade union movement, Douglas was incandescent at the perceived abandonment of labour by Labour, and decided to wade back into the party to agitate from within. Lee – Douglas’ business partner in the booksellers they’d set up together in 1944 – approved of this, his immense ego seeing it as a way to manoeuvre a proxy into the commanding heights of the party and eventually bring about Truer Socialism. On the other side of events, and looking to broaden the party’s support and reconcile feuding factions he’d been sympathetic to at one time or another, Nordmeyer decided it would look rather good in the lead-up to 1952 to try and make sure the unions were firmly back on side: welcoming Douglas, a former secretary of the Brewers, Wine and Spirit Merchants’ Employees’ Union, the Coach and Car Builders’ Union, and the Auckland Trades Council, back in from the cold sent a good signal. After the Bloody Budget – during which Douglas, as a representative of the working-class wing of the party who stood to lose the most from raising taxes on the common man’s pleasures, made a name for himself as a stalwart of the workers – Big Norm began to emerge as a potential contender for the leadership.

So when a vote of no confidence was launched against Nordmeyer in 1963, Douglas emerged as the darling of the party’s leftist-conservative wings, promising to keep the party on the formula which had worked for it so far: social security for all, damn the Tories, keep on selling to the Brits and

maybe the Yanks. It didn’t take so well in 1965 – Marshall was unassailable on the grounds of policy or personality, having yet to make his commitment to Vietnam – but in 1963 it certainly looked good enough to the riled left (the 1951 affray remains the most public instance of internal dissent within Labour, as branches up and down the country held bitterly-debated votes on the unions’ proposed action) to support Douglas. And so, after three kaleidoscopic ballots, Norman Douglas came from the rear, sweeping aside his competition (Little Norm was seen as inexperienced, Nash was past it, Mason was loyal to Nordmeyer and refused to have his name put forward, Skinner had unexpectedly dropped dead in 1962, and nobody else was really prominent enough to take the stand) and becoming leader.

All of this meant that the old one-armed bandit, as he was often known, was the most working-class PM the country had had in decades, possibly ever. His nasal drawl lacked the stentorian qualities of Holyoake, but was reminiscent of Marshall’s faintly rasping voice and Nordy’s straight talking. Although usually soft-spoken in the manner of Marshall, Douglas was also more prone than most of his predecessors to getting roused into fiery rhetoric, a quality which allowed him to take the fight to Gentleman Jack on the televised 1968 election debate. Although he was seen as rude by many National supporters, the fire in his belly he showed when responding quite passionately to a question on the subject of the voluntary union scheme gave people confidence in his ability to lead the country quite capably.

For a while, it seemed like he’d do just fine: 1969 was the peak of Big Norm’s popularity, not least due to the referendum which led the government to end six o’clock closing in pubs. But it wasn’t just alcoholism; atop the wave of booze floated a raft of social security policies comprising a Domestic Purposes Benefit (right-wing readers: please direct your hate mail to the editor, who will delight in giving me live readings of your comments), incentives for rural GPs, a national shipping company, utility price controls, a removal of practically all penalties on strike and union actions, the abolition of National Service, a disability allowance, and so on and so forth.

Where the Third Labour Government failed – and indeed signed its own death warrant – was its abject failure to navigate Britain’s accession to the European Economic Community, forerunner to today’s European Union. While Marshall had famously “caught the first flight to London” in 1961 when Britain first expressed an interest in joining, and campaigned throughout his time in office on New Zealand’s behalf to keep open a number of options and exceptions to maintain continued tariff-free access for New Zealand agricultural goods to the UK market. Pulling New Zealand’s soldiers out of Vietnam, although it was domestically popular and medical forces remained, did not help the cause of trade diversification either in regard to Australia or the US.

It’s not so much that the Third Labour Government didn’t see these issues – by 1968 you had to be blind not to see them coming – but rather that it had prioritised domestic concerns over maintaining New Zealand’s international commitments. Little Norm did his damnedest as Minister of Foreign Affairs to remind Big Norm of the external realities facing New Zealand as he advocated on the world stage for New Zealand’s “moral foreign policy”, but Douglas was nothing if not determined. He was devoted to expanding the welfare net in a way nobody since Nash had been, and that was where his intrinsic tragedy lies: unionism was the only way he knew how to bring that about, but their time as the primary vehicle of people’s wellbeing was passing.

The Third Labour Government has been called “the last of the traditional Labour governments”, and to a large extent this is true. Big Norm was the last gasp of the “Big Union” phase of the Labour Party, with the backlash against the power of unions leading him to make the comment I’ve quoted today. Listening to the interview where he said it you get a sense of his disillusionment and disappointment in the New Zealand worker for it; here is a man who is accepting that the order he had worked to bring about for his entire adult life is no longer desired by those for whose benefit it was designed. While he accepted it with a certain graceful resignation, it didn’t make for an inspiring governing choice, knowing that the PM didn’t entirely believe in the choices forced upon him by caucus and the electorate. People certainly knew or at least felt by 1971 that Big Norm and the Labour Party cared about them, but they also felt that the way in which that care was expressed was not the right way.

National made a lot of political hay from Douglas’ socialism, with the Dancing Cossacks ad shown during the election campaign playing on the faint rumours of his ties to Moscow. Whether or not it worked, Labour was doomed. The election was a shambles, with attempts to paint National as opportunists failing to resonate with the nation’s mood as news broke of Britain securing EEC membership and the economy looked to be in doubt. Come election night, Labour had lost in a landslide, with strongholds like Mount Albert falling to the blue wave. Douglas was promptly ‘encouraged’ to step down into the obscurity where he remained for the rest of his life, and Labour fell into an identity crisis as the 1970s stretched languidly along. National was back in the saddle, and would stay there for twelve long years.