its a map!

And a double whammy, I've got a post to update you with as well!

The Aquitainian Rebellion

The Lankan capture of Olizpo [Lisbon] and the Amuricushi invasion that followed on its heels put the Ispanian state on the back foot. The Amuricushi were able to take Gades and Valencia by surprise, seizing most of Ispania's southern coast and putting the Straits of Gibraltar under their sole control. At first, King Francisau and his court dithered, knowing the Moors had ill intentions, but completely unable to read the intentions of the Lankans. As the Lankan fleet remained in port, however, it was decided the Moors were the larger threat, and the Ispanian army under Duke Tomas of Toledo fended off the Moorish expeditionary force just outside of Cortoba. They might have pushed forward and expelled the invasion there, but word had reached Saragosta of a new problem...

The nobles of Aquitaine had found their tacit acceptance of division at the hands of the Burgundians and Spaniards had bought them nothing but penury and ever-lower expectations. The flow of New World silver into Bordeu had, for the most part, stopped after the exile of the Golden Fleet and the de Agdes' supporters. Once a contender for cultural capital of Europe, the city was now decidedly shabbier, littered with the hulks of half-finished construction projects which had not seen work for decades. Aquitaine's other possessions, its sugar islands in particular, had also passed under Ispanian control and now sent their tariffs to Saragosta. Many of the supporters and opponents of King Alphonse alike had found their fortunes ruined by the Ispanian embargo of New Aquitaine, and after the failed Ispanian invasion of that kingdom, a fair number attempted to elude the Ispanian embargo (often through Breton and Vasconian intermediaries) and sailed to New Aquitaine regardless, taking possession of lands their families had, until then, been absentee landlords of. Thus there were many noble families with branches on both sides of the Atlantic and who maintained a continual, if attenuated, correspondence with each other. Those who remained in Aquitaine, then, saw an opportunity in Ispania's ongoing humiliation....

Aquitaine's orphan daughter, New Aquitaine, while massively successful through sheer weight of silver, still had several critical strategic weaknesses. It had a critical shortage of skilled manpower, particular of those skilled enough in the maintenance of Old World crops and livestock, and especially in skilled manufacturers and guildsmen. The Chimor and increasingly, a select few other ethnic groups like the Chincha had become acquainted in these skills, but the state's wide expansion threatened to stretch their small numbers thin. African, and later, southeast Asian slaves would fill this gap. More than this, though, none of these groups (other than, to an extent, the Chimor) could really be trusted to fight, and so this more than anything else left them hungering for Europeans to act as soldiers, leading to the model of "franchise feudalism" that recruited from the Frankish heartlands and Angland, and to their dependence on martial orders like the Lorenzian Brothers and the Knights of St. Peter. But New Aquitiane was running out of new lands to grant Votive venturers. Furthermore, they maintained little naval presence in the Atlantic beyond a bare bones coast guard; the Moors, and to a lesser degree the Antillians, Knights and Bretons served as their de facto navy and merchant fleet there - and amply took their cut. New Aquitaine had adapted to its orphanhood, but its ruler, Emperor Jerome, was always reminded of the loss of the motherland.

Things came to a head after the proclamation of Pope John XXII in Rome. Exarch Leo II of Sardinia, of the cadet Tolosa branch of the de Agde dynasty, was one of the first European rulers to recognize the new Pope. Sardinia, after the Division of Aquitaine, had become another home for exiled de Agde loyalists and various malcontents from the Northern Papal order. They were a close ally of the Two Africas, whose other allies, the "holy republics" in the boot and heel of Italy, had also fallen behind the new Pope. The Two Africas' ruler, King Warmaksanes, also had reason to dislike the Northern order; it was widely resented, for example, that the Pope had never granted official recognition of New World claims to anyone outside the old Frankish realm (which was also a point of contention for other realms like Angland and Denmark [1]). Furthermore, the Mauri people broadly had a greater sympathy for the more heterodox and egalitarian ideas coalescing around the Southern Pope. Thus it was not hard for Exarch Leo II to bring together a plot bringing all these elements together...

With confirmation of foreign support (including large donations of silver channeled through the New World branch of the Knights of St Peter) the new Pope's backers discussed how to respond to the Pope in Aachen, Urban III's, proclamation of excommunication for the so-called "anti-pope" and his followers. In consultation with his council and the magnates of Rome, including Grand Prior Ignacio of the Italian Langue of the Knights of St Peter, and the Nuncio of the Novaquitianian Langue[2], the Pope in Rome, John XXII, would be moved to make a proclamation excommunicating Urban III in turn, and denouncing a number of "worldly" acts and policies of the Northern Papacy, such as the Division of Aquitaine, the sale of Church offices to power-hungry nobles, and the use of Papal slave soldiers as tax farmers (which weighed heavily on Neustria and the Rhineland in particular[3]), calling for a new Ecumenical Council be called in Rome to discuss the issues of the Church in the Votive Age and concluding with a withering critique of Pope Urban III and his predecessors, lamenting the "Babylonian Captivity of the Mother Church by the Counterfeit Patriarchs of Aachen" (this passage was believed to be written by Grand Prior Ignacio himself.)

This was the opportunity the de Agdes had been waiting for. With the promise of the backing of both the Pope of Rome and New Aquitaine, long-laid plans were moved into action. In 1364, Count Luic of Gironde led a small force of de Agde loyalists and Breton mercenaries to capture the citadel of the Ispanian viceroy in Bordeu, and proclaimed his support for the Southern Pope, and for the rightful ruler of Aquitaine, Emperor Jerome de Agde. Other loyalists, acting out of Brittany and Pictavia to the north, mounted incursions of their own.

Now, Emperor Jerome did not have any shortage of problems to attend to already; in Tolteca, the Chicomoztoca and the Chimalhuacan were on the march, and in the south, a major Aymara revolt was brewing. Yet, it was said, he was one who always had the flash of new crowns in his eyes. Therefore, when word of the seizure of Bordeu reached him, he sailed to the Knights' ostensibly neutral stronghold of Sant-Bartolomeu [Tobago] on the remaining vessels of the old Golden Fleet, along with a chartered Moorish flotilla. There, he gathered a collection of men, including a large number of Knights and Lorenzian native auxillaries, and Anglo-Norse, Frankish, and Moorish mercenaries. His general, Valentin Garat, led a cohort that sailed first to take back St Joan [St Lucia] and the Islas Sucradas [Grenadines], then sailed on to Bordeu. Emperor Jerome sailed with the remaining cohort shortly after.

His landing sparked celebrations that one day would later inspire many famous paintings; proto-national and religious fervor became merged on the figure of Jerome returning as liberator from across the sea. This won their hearts; his generosity in silver won their purses. Emperor Jerome settled in to establish court in Bordeu, while Valentin Garat and the Count of Gironde led an army inland to liberate Tolosa. Yet, he found his new throne awkward, especially at first. Jerome, now getting on in years, had last seen Aquitaine as a young boy, when he was smuggled out from his relatives' home by de Agde loyalists. He had become used to having an army of native attendees and riding in a palanquin as their magnates did; and used to having cooperative, subservient nobles, who accepted his dictates with little pushback; this led him to make some major faux pas in his popular and political relations. Nevertheless, de Agde power and money helped smoothed this over, along with his own not inconsiderable personal charm, and his position was bolstered after Tolosa fell and his forces repulsed a hastily assembled Ispanian army crossing the Pyrennes near the Garats' old family seat, the original Morlans.

Emperor Jerome was excommunicated by Northern Pope Urban III after news of his landing reached Aachen. This forced open multiple faultlines within the church and its hierarchy. The Knights, in particular, suffered fraught internal division; the Novaquitainean tail had started to wag the European dog. The Nuncio of the New Aquitainian Langue had wide influence with the Roman nobility, thanks to the influence of New World silver renovating the port of Ostia and many other places in and around Rome. And, de facto, this branch of the Order was simultaneously a branch of the Novaquitainian state, owning vast estates in the Andes, particularly the frontier regions. The current Grandmaster of the Order, Agostin de Icosi, was Mauri in background and also sympathetic to Pope John XXII. Yet the Grand Priors of many Langues remained loyal to the Northern Pope and vicious infighting broke out among the leadership, and the Grand Prior of Italy and the Nuncio of New Aquitaine were excommunicated; Grand Master Agostin was himself, in turn, excommunicated for refusing to remove them from their positions.

This led to a schism in the Order; The Ispanians, feeling vindicated on treating the Knights like a fifth column, seized their assets in Ispania (at least, those not behind Amurichushi lines.) The Burgundian, Rhaetian, and other northern Langues fell behind the new, Pope Urban-approved Grandmaster (former Grand Prior of Burgundy) Bernard of Lyons, while the others fell in solidly with Grandmaster Agostin or were evenly divided. The split permeated down to the ground level, though, and there was a period of chaos where vessels and men defected to one side or another, sometimes multiple times. Knight-on-Knight violence broke out in divided commanderies like those of Niza and Mantova. Unit cohesion, in the Mediterranean branch at least, suffered a blow it would not quickly recover from. The commanderies of Arles and Barcino became refuges for Pope Urban III's loyalists from across the Mediterranean (and also kept the Count of Barcino firmly in the Northern camp...)

The Burgundians, solid Northern backers to begin with, entered the war quickly, knowing Jerome would soon come calling for their half of Aquitaine as well. They sent a large and well-trained army to march on Tolosa, with the Pope's blessing. On the other hand, King Giovanni of Italy, of the same dynasty, had been taken by surprise by the news of the new Pope's ascent, and dithered on how to respond, giving the Roman Pope's faction hope he would declare for their side; meanwhile, Grand Prior Ignacio of Italian Langue consolidated control of the Knights' extensive fortresses and holdings in Italy, including the fortress of Heneto [Venice]; the Northern Loyalists would organize around the commandery of Medilano. When King Giovanni eventually, on the urging of his co-dynasts, came down on the side of the Pope in Aachen, revolts broke out in Pisa, Siena, and other Italian cities. The Italian Knights, accustomed from their beginning to acting covertly against the state, lent their support to these revolts and the Italian Langue widely recruited among the rebels and turned into something of a religious mob (in more than one sense of the word), to a degree that disconcerted even Grandmaster Agostin, as "Holy Republics" were proclaimed in Pisa, Siena, and Genua under various local nobles and holy men. With the Italian kingdom in chaos, the Free City of Ravenna moved to expand its territory, and King Giovanni penned a desperate letter for help to Burgundy.

Exarch Leo II landed a Sardinian-Mauri force at Narbo shortly after Jerome's arrival in Europe, and deposed the Burgundian Legate, allowing the Conseila to declare support for Aquitaine. Jerome's forces were battle-hardened from the New World, but comparatively few in number, while Burgundy had many well-trained knights; thus the Burgundians were able to best the Aquitainians outside of Carcassona and prevent them from linking up with the Sardinians and Narbonese. Yet, they were unable to decisively crush Jerome and his forces either, being distracted by the outbreak of rebellion in Italy, and moved to send their armies to help their co-dynasts in the west. Leo II would strike again, landing in Provence and securing the support of its own Exarch to re-assert its old privileges versus the Kings of Burgundy, and the Burgundians would be further split fighting in the south.

Jerome, now in secure control of most of Aquitaine, moved to reward his supporters. His general, Valentin Garat, would be made new Count of his family's ancestral Bearn; the Count of Gironde was promised the currently-defunct County of Auvernia, which belonged to Burgundy for now. He ruffled some feathers in Narbo when he even appointed one of his generals, Petre Aznar, as their new Legate. Petre, who was used to having the run of his vast rural family lands around Lake Nicoya [Nicaragau], might have initially seemed a poor fit to negotiate with the fractious Conseila, but he quickly developed a rapport with many of the younger members of the Conseila through his boisterous style, and this, along with the prospect of lower taxes(the Aquitanians could afford to be generous...) and access to New World markets, was enough to get the Narbonese to firmly commit to being part of the Aquitanian state again.

Jerome could not rest easy, however, for the armies of Neustria, and behind them, of Pope Urban III himself, were now on the march....

[1]As far as the Pope was concerned, the Twin Crowns were rightful rulers of all of North Solvia, no matter that these claims were treated as a joke by the Anglo-Norse who had lived there for more than two hundred years now.

[2]Representing the Grand Prior, who himself lived in Morlans

[3]More on this in a future post...

Meet the New Boss- Nova Ispania Edition

The war with Lanka had not gone well for Ispania, to say the least. Her naval forces defeated, her colonial fortresses would prove vulnerable to bombardment from the sea - as had Olizpo itself. The Red Swans and the Moors took advantage of this weakness; a combined Moorish-Red Swan fleet sailed from Haiti, landing first at the Moorish freeport of Casteddu [Natal]. From there, the fleet moved south along the coast, sailing to Gaundere [Maceió] and captured that port as well, here, they proclaimed the rebirth of the old kingdom of Tatolamaayo (or simply Tatola), under a Fula noble of their choosing. Raising a small band of Fula cavalrymen, Tupi scouts, and Moorish tufenjeras, the fleet then sailed south to San Valentino [Recife] and bombarded the Ispanian Capitan-General's citadel. When he surrendered, the Moors were able to seize the armory and distribute weapons to their catspaws. The fleet continued its path south, where they were able to reinforce the other major freeport of Anfa [Salvador], liberate Galdugo in a similar fashion, and finally retake La Tomzepanda [Sao Paolo] - which the Red Swans reinstated as their own freeport of Rakhtahamsabandara.

Kumaraya Ratta, admiral of the Lankan fleet occupying Olizpo, now was now faced with a decision. Having humiliated Ispania, he was now forced to decide what, exactly, he wanted from it. Amuricushi ambassadors, seeking him out discreetly, would urge him to march on, and decapitate the Ispanian state completely. Yet, he could find no quick and simple profit in that.... and he was already operating way beyond his purview. When the Ispaniards sent an emissary to discuss terms, he demanded the right to establish Lankan ports, levy tariffs, and trade freely in Nova Ispania, basing rights in Ferislanda and Figenlanda [the Azores and Madiera], and a host of other economic concessions besides. Facing down invasions in the north and south, the Ispanians still balked, and sent a fleet to attempt to dislodge the Lankans, to similar disastrous results. This led them to, grudgingly, accept the Indian admiarl's terms. Yet, no sooner had the Lankan fleet departed Olizpo, than a Moorish one sailed in - a courtesy for which, it was rumored, several chests of New Aquitaine's finest silver had changed hands.

Returning to South Solvia, Kumaraya Ratta found a changed landscape - the Moors and Red Swans had claimed his prize before he could. Nevertheless, Kumaraya's confidence had swelled with victory, and he presented the Moorish and Red Swan representatives with his treaty with Ispania, giving Lanka what amounted to overlordship in all but name of Nova Ispania. After some deliberation an accommodation was worked out with the Moors; the kingdoms of Tatola and Galodugu would pay tribute to Lanka, while the Moorish freeports and plantations continued to operate, now with an even freer hand. The Lankans would receive a special 25% duty on all sugar and dye going east past Cape Watya, enforced by means of an official stamp given at Sihanuwara, which would thus become a mandatory transshipment and stopover point for most Moorish traders.

The Red Swans proved less accommodating; having won their long-lost possession back at last, they were unwilling to so easily give up its profits. In this case - unlike with the Moors or Ispania - starting a war would have repercussions with their mother city of Khambayat, and thus with Chandratreya, bringing the consequences closer to home. Thus, after leaving a delegation of troops to found a settlement at Jayagrāhī Varāya - the "Port of Victory" [Porto Alegre] - he returned to the Cape, where he received news that war might soon come to Watyan waters anyway, by way of the Kapudesan cities' conflict with the overweening Musengezi....

On the ground, not as much changed for the inhabitants of Nova Ispania as might be expected. The Captaincy of San Marcos and points west, for instance, continued for now under Ispanian rule, as they had not been visited again since the disastrous naval battle with the Lankan fleet. In the revived Fula kingdoms, their new rulers were nominally Christian and fluent in the local Ispanian creole, while the "Iberios" - the now-plurality of the population that claimed mostly Ispanian descent - remained extremely prominent, and even more so, the Moors. The biggest change was a shift in power from aristocratic governors and bureaucrats generally sent from Ispania, to local land magnates who often had extensive marriage ties to Fula and Tupi clans. These magnates would provide many advisors for the kings of Tatola and Galodugu and, indeed, were just as important as the Fula themselves to their rule. Inland, the herdsman kingdom of Binyaala - which, receiving many escaped slaves, had taken on aspects of a maroon colony - remained just as opposed to colonial expansion, but now Moorish arms held their raids at bay, rather than Ispanian ones.

In Raktahamsabandara, things would not remain so peaceful. Over a dozen years of Ispanian occupation, the Christian minority had built up a rather lot of bad blood with the predominately Hindu inhabitants. After the liberation of the port, vengeful Hindus and Buddhists had looted and burned the Cathedral of St James, and vandalized nearly every other church. The Christians, meanwhile, would answer tit-for-tat, assassinating the Red Swan governor in the middle of the night. It is likely that there would have been a general massacre of the Christians had not the head of the local Mauri merchant interest stepped forward and offered to transport any willing Christians to his family's estates on Isla Pasca [St Helena]. The deputy governor, now no longer a deputy, agreed, and so the majority of the Christians then present in the city would come to leave. The Mauri presence, though, would come to grow, and in time the Christian community in the city became almost as large as before...

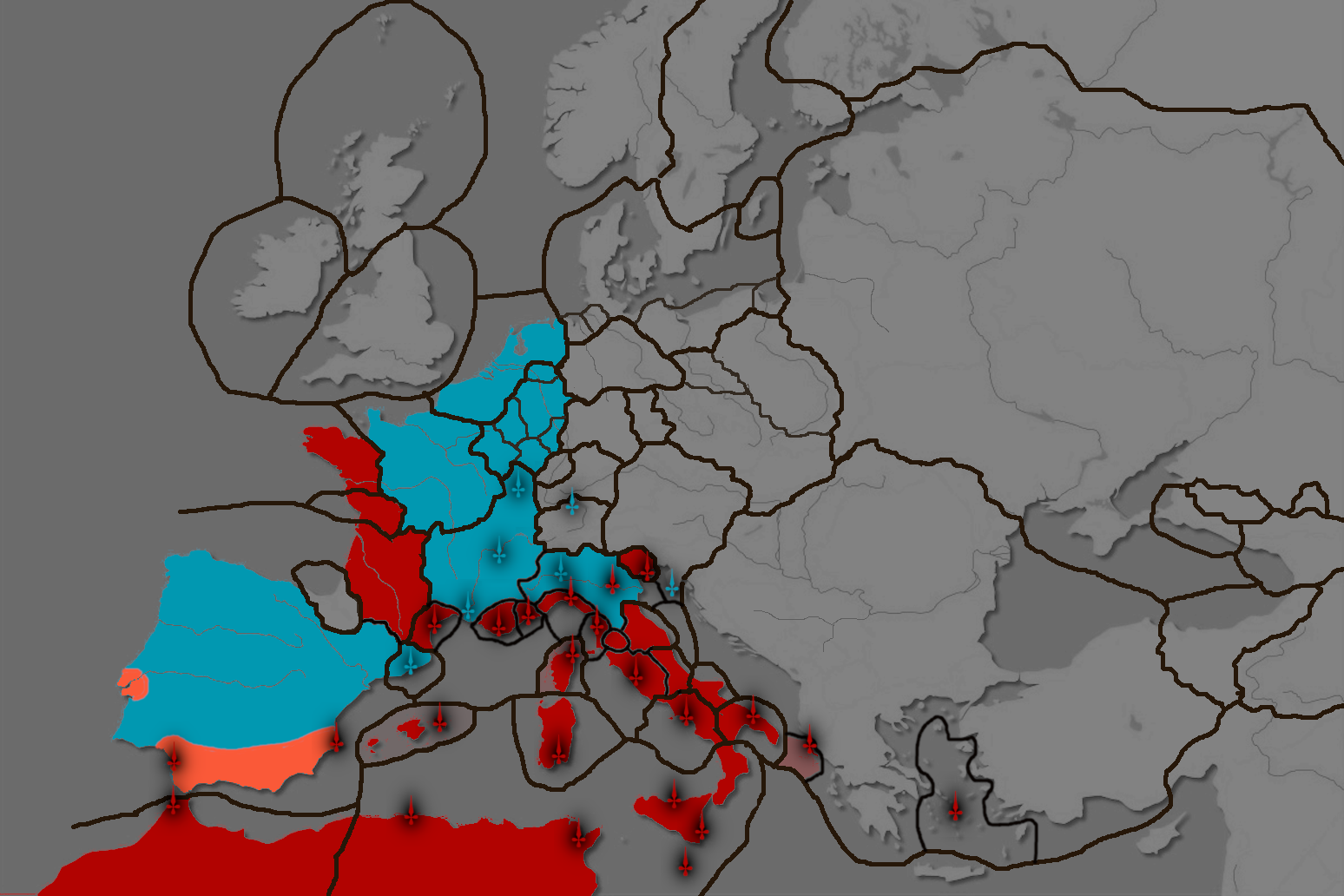

Map of the coalitions in 1365 of the War of the Popes, including major Knights naval bases and fortresses. No labels, will likely make a larger version with them once the war shakes out...

The Aquitainian Rebellion

The Lankan capture of Olizpo [Lisbon] and the Amuricushi invasion that followed on its heels put the Ispanian state on the back foot. The Amuricushi were able to take Gades and Valencia by surprise, seizing most of Ispania's southern coast and putting the Straits of Gibraltar under their sole control. At first, King Francisau and his court dithered, knowing the Moors had ill intentions, but completely unable to read the intentions of the Lankans. As the Lankan fleet remained in port, however, it was decided the Moors were the larger threat, and the Ispanian army under Duke Tomas of Toledo fended off the Moorish expeditionary force just outside of Cortoba. They might have pushed forward and expelled the invasion there, but word had reached Saragosta of a new problem...

The nobles of Aquitaine had found their tacit acceptance of division at the hands of the Burgundians and Spaniards had bought them nothing but penury and ever-lower expectations. The flow of New World silver into Bordeu had, for the most part, stopped after the exile of the Golden Fleet and the de Agdes' supporters. Once a contender for cultural capital of Europe, the city was now decidedly shabbier, littered with the hulks of half-finished construction projects which had not seen work for decades. Aquitaine's other possessions, its sugar islands in particular, had also passed under Ispanian control and now sent their tariffs to Saragosta. Many of the supporters and opponents of King Alphonse alike had found their fortunes ruined by the Ispanian embargo of New Aquitaine, and after the failed Ispanian invasion of that kingdom, a fair number attempted to elude the Ispanian embargo (often through Breton and Vasconian intermediaries) and sailed to New Aquitaine regardless, taking possession of lands their families had, until then, been absentee landlords of. Thus there were many noble families with branches on both sides of the Atlantic and who maintained a continual, if attenuated, correspondence with each other. Those who remained in Aquitaine, then, saw an opportunity in Ispania's ongoing humiliation....

Aquitaine's orphan daughter, New Aquitaine, while massively successful through sheer weight of silver, still had several critical strategic weaknesses. It had a critical shortage of skilled manpower, particular of those skilled enough in the maintenance of Old World crops and livestock, and especially in skilled manufacturers and guildsmen. The Chimor and increasingly, a select few other ethnic groups like the Chincha had become acquainted in these skills, but the state's wide expansion threatened to stretch their small numbers thin. African, and later, southeast Asian slaves would fill this gap. More than this, though, none of these groups (other than, to an extent, the Chimor) could really be trusted to fight, and so this more than anything else left them hungering for Europeans to act as soldiers, leading to the model of "franchise feudalism" that recruited from the Frankish heartlands and Angland, and to their dependence on martial orders like the Lorenzian Brothers and the Knights of St. Peter. But New Aquitiane was running out of new lands to grant Votive venturers. Furthermore, they maintained little naval presence in the Atlantic beyond a bare bones coast guard; the Moors, and to a lesser degree the Antillians, Knights and Bretons served as their de facto navy and merchant fleet there - and amply took their cut. New Aquitaine had adapted to its orphanhood, but its ruler, Emperor Jerome, was always reminded of the loss of the motherland.

Things came to a head after the proclamation of Pope John XXII in Rome. Exarch Leo II of Sardinia, of the cadet Tolosa branch of the de Agde dynasty, was one of the first European rulers to recognize the new Pope. Sardinia, after the Division of Aquitaine, had become another home for exiled de Agde loyalists and various malcontents from the Northern Papal order. They were a close ally of the Two Africas, whose other allies, the "holy republics" in the boot and heel of Italy, had also fallen behind the new Pope. The Two Africas' ruler, King Warmaksanes, also had reason to dislike the Northern order; it was widely resented, for example, that the Pope had never granted official recognition of New World claims to anyone outside the old Frankish realm (which was also a point of contention for other realms like Angland and Denmark [1]). Furthermore, the Mauri people broadly had a greater sympathy for the more heterodox and egalitarian ideas coalescing around the Southern Pope. Thus it was not hard for Exarch Leo II to bring together a plot bringing all these elements together...

With confirmation of foreign support (including large donations of silver channeled through the New World branch of the Knights of St Peter) the new Pope's backers discussed how to respond to the Pope in Aachen, Urban III's, proclamation of excommunication for the so-called "anti-pope" and his followers. In consultation with his council and the magnates of Rome, including Grand Prior Ignacio of the Italian Langue of the Knights of St Peter, and the Nuncio of the Novaquitianian Langue[2], the Pope in Rome, John XXII, would be moved to make a proclamation excommunicating Urban III in turn, and denouncing a number of "worldly" acts and policies of the Northern Papacy, such as the Division of Aquitaine, the sale of Church offices to power-hungry nobles, and the use of Papal slave soldiers as tax farmers (which weighed heavily on Neustria and the Rhineland in particular[3]), calling for a new Ecumenical Council be called in Rome to discuss the issues of the Church in the Votive Age and concluding with a withering critique of Pope Urban III and his predecessors, lamenting the "Babylonian Captivity of the Mother Church by the Counterfeit Patriarchs of Aachen" (this passage was believed to be written by Grand Prior Ignacio himself.)

This was the opportunity the de Agdes had been waiting for. With the promise of the backing of both the Pope of Rome and New Aquitaine, long-laid plans were moved into action. In 1364, Count Luic of Gironde led a small force of de Agde loyalists and Breton mercenaries to capture the citadel of the Ispanian viceroy in Bordeu, and proclaimed his support for the Southern Pope, and for the rightful ruler of Aquitaine, Emperor Jerome de Agde. Other loyalists, acting out of Brittany and Pictavia to the north, mounted incursions of their own.

Now, Emperor Jerome did not have any shortage of problems to attend to already; in Tolteca, the Chicomoztoca and the Chimalhuacan were on the march, and in the south, a major Aymara revolt was brewing. Yet, it was said, he was one who always had the flash of new crowns in his eyes. Therefore, when word of the seizure of Bordeu reached him, he sailed to the Knights' ostensibly neutral stronghold of Sant-Bartolomeu [Tobago] on the remaining vessels of the old Golden Fleet, along with a chartered Moorish flotilla. There, he gathered a collection of men, including a large number of Knights and Lorenzian native auxillaries, and Anglo-Norse, Frankish, and Moorish mercenaries. His general, Valentin Garat, led a cohort that sailed first to take back St Joan [St Lucia] and the Islas Sucradas [Grenadines], then sailed on to Bordeu. Emperor Jerome sailed with the remaining cohort shortly after.

His landing sparked celebrations that one day would later inspire many famous paintings; proto-national and religious fervor became merged on the figure of Jerome returning as liberator from across the sea. This won their hearts; his generosity in silver won their purses. Emperor Jerome settled in to establish court in Bordeu, while Valentin Garat and the Count of Gironde led an army inland to liberate Tolosa. Yet, he found his new throne awkward, especially at first. Jerome, now getting on in years, had last seen Aquitaine as a young boy, when he was smuggled out from his relatives' home by de Agde loyalists. He had become used to having an army of native attendees and riding in a palanquin as their magnates did; and used to having cooperative, subservient nobles, who accepted his dictates with little pushback; this led him to make some major faux pas in his popular and political relations. Nevertheless, de Agde power and money helped smoothed this over, along with his own not inconsiderable personal charm, and his position was bolstered after Tolosa fell and his forces repulsed a hastily assembled Ispanian army crossing the Pyrennes near the Garats' old family seat, the original Morlans.

Emperor Jerome was excommunicated by Northern Pope Urban III after news of his landing reached Aachen. This forced open multiple faultlines within the church and its hierarchy. The Knights, in particular, suffered fraught internal division; the Novaquitainean tail had started to wag the European dog. The Nuncio of the New Aquitainian Langue had wide influence with the Roman nobility, thanks to the influence of New World silver renovating the port of Ostia and many other places in and around Rome. And, de facto, this branch of the Order was simultaneously a branch of the Novaquitainian state, owning vast estates in the Andes, particularly the frontier regions. The current Grandmaster of the Order, Agostin de Icosi, was Mauri in background and also sympathetic to Pope John XXII. Yet the Grand Priors of many Langues remained loyal to the Northern Pope and vicious infighting broke out among the leadership, and the Grand Prior of Italy and the Nuncio of New Aquitaine were excommunicated; Grand Master Agostin was himself, in turn, excommunicated for refusing to remove them from their positions.

This led to a schism in the Order; The Ispanians, feeling vindicated on treating the Knights like a fifth column, seized their assets in Ispania (at least, those not behind Amurichushi lines.) The Burgundian, Rhaetian, and other northern Langues fell behind the new, Pope Urban-approved Grandmaster (former Grand Prior of Burgundy) Bernard of Lyons, while the others fell in solidly with Grandmaster Agostin or were evenly divided. The split permeated down to the ground level, though, and there was a period of chaos where vessels and men defected to one side or another, sometimes multiple times. Knight-on-Knight violence broke out in divided commanderies like those of Niza and Mantova. Unit cohesion, in the Mediterranean branch at least, suffered a blow it would not quickly recover from. The commanderies of Arles and Barcino became refuges for Pope Urban III's loyalists from across the Mediterranean (and also kept the Count of Barcino firmly in the Northern camp...)

The Burgundians, solid Northern backers to begin with, entered the war quickly, knowing Jerome would soon come calling for their half of Aquitaine as well. They sent a large and well-trained army to march on Tolosa, with the Pope's blessing. On the other hand, King Giovanni of Italy, of the same dynasty, had been taken by surprise by the news of the new Pope's ascent, and dithered on how to respond, giving the Roman Pope's faction hope he would declare for their side; meanwhile, Grand Prior Ignacio of Italian Langue consolidated control of the Knights' extensive fortresses and holdings in Italy, including the fortress of Heneto [Venice]; the Northern Loyalists would organize around the commandery of Medilano. When King Giovanni eventually, on the urging of his co-dynasts, came down on the side of the Pope in Aachen, revolts broke out in Pisa, Siena, and other Italian cities. The Italian Knights, accustomed from their beginning to acting covertly against the state, lent their support to these revolts and the Italian Langue widely recruited among the rebels and turned into something of a religious mob (in more than one sense of the word), to a degree that disconcerted even Grandmaster Agostin, as "Holy Republics" were proclaimed in Pisa, Siena, and Genua under various local nobles and holy men. With the Italian kingdom in chaos, the Free City of Ravenna moved to expand its territory, and King Giovanni penned a desperate letter for help to Burgundy.

Exarch Leo II landed a Sardinian-Mauri force at Narbo shortly after Jerome's arrival in Europe, and deposed the Burgundian Legate, allowing the Conseila to declare support for Aquitaine. Jerome's forces were battle-hardened from the New World, but comparatively few in number, while Burgundy had many well-trained knights; thus the Burgundians were able to best the Aquitainians outside of Carcassona and prevent them from linking up with the Sardinians and Narbonese. Yet, they were unable to decisively crush Jerome and his forces either, being distracted by the outbreak of rebellion in Italy, and moved to send their armies to help their co-dynasts in the west. Leo II would strike again, landing in Provence and securing the support of its own Exarch to re-assert its old privileges versus the Kings of Burgundy, and the Burgundians would be further split fighting in the south.

Jerome, now in secure control of most of Aquitaine, moved to reward his supporters. His general, Valentin Garat, would be made new Count of his family's ancestral Bearn; the Count of Gironde was promised the currently-defunct County of Auvernia, which belonged to Burgundy for now. He ruffled some feathers in Narbo when he even appointed one of his generals, Petre Aznar, as their new Legate. Petre, who was used to having the run of his vast rural family lands around Lake Nicoya [Nicaragau], might have initially seemed a poor fit to negotiate with the fractious Conseila, but he quickly developed a rapport with many of the younger members of the Conseila through his boisterous style, and this, along with the prospect of lower taxes(the Aquitanians could afford to be generous...) and access to New World markets, was enough to get the Narbonese to firmly commit to being part of the Aquitanian state again.

Jerome could not rest easy, however, for the armies of Neustria, and behind them, of Pope Urban III himself, were now on the march....

[1]As far as the Pope was concerned, the Twin Crowns were rightful rulers of all of North Solvia, no matter that these claims were treated as a joke by the Anglo-Norse who had lived there for more than two hundred years now.

[2]Representing the Grand Prior, who himself lived in Morlans

[3]More on this in a future post...

Meet the New Boss- Nova Ispania Edition

The war with Lanka had not gone well for Ispania, to say the least. Her naval forces defeated, her colonial fortresses would prove vulnerable to bombardment from the sea - as had Olizpo itself. The Red Swans and the Moors took advantage of this weakness; a combined Moorish-Red Swan fleet sailed from Haiti, landing first at the Moorish freeport of Casteddu [Natal]. From there, the fleet moved south along the coast, sailing to Gaundere [Maceió] and captured that port as well, here, they proclaimed the rebirth of the old kingdom of Tatolamaayo (or simply Tatola), under a Fula noble of their choosing. Raising a small band of Fula cavalrymen, Tupi scouts, and Moorish tufenjeras, the fleet then sailed south to San Valentino [Recife] and bombarded the Ispanian Capitan-General's citadel. When he surrendered, the Moors were able to seize the armory and distribute weapons to their catspaws. The fleet continued its path south, where they were able to reinforce the other major freeport of Anfa [Salvador], liberate Galdugo in a similar fashion, and finally retake La Tomzepanda [Sao Paolo] - which the Red Swans reinstated as their own freeport of Rakhtahamsabandara.

Kumaraya Ratta, admiral of the Lankan fleet occupying Olizpo, now was now faced with a decision. Having humiliated Ispania, he was now forced to decide what, exactly, he wanted from it. Amuricushi ambassadors, seeking him out discreetly, would urge him to march on, and decapitate the Ispanian state completely. Yet, he could find no quick and simple profit in that.... and he was already operating way beyond his purview. When the Ispaniards sent an emissary to discuss terms, he demanded the right to establish Lankan ports, levy tariffs, and trade freely in Nova Ispania, basing rights in Ferislanda and Figenlanda [the Azores and Madiera], and a host of other economic concessions besides. Facing down invasions in the north and south, the Ispanians still balked, and sent a fleet to attempt to dislodge the Lankans, to similar disastrous results. This led them to, grudgingly, accept the Indian admiarl's terms. Yet, no sooner had the Lankan fleet departed Olizpo, than a Moorish one sailed in - a courtesy for which, it was rumored, several chests of New Aquitaine's finest silver had changed hands.

Returning to South Solvia, Kumaraya Ratta found a changed landscape - the Moors and Red Swans had claimed his prize before he could. Nevertheless, Kumaraya's confidence had swelled with victory, and he presented the Moorish and Red Swan representatives with his treaty with Ispania, giving Lanka what amounted to overlordship in all but name of Nova Ispania. After some deliberation an accommodation was worked out with the Moors; the kingdoms of Tatola and Galodugu would pay tribute to Lanka, while the Moorish freeports and plantations continued to operate, now with an even freer hand. The Lankans would receive a special 25% duty on all sugar and dye going east past Cape Watya, enforced by means of an official stamp given at Sihanuwara, which would thus become a mandatory transshipment and stopover point for most Moorish traders.

The Red Swans proved less accommodating; having won their long-lost possession back at last, they were unwilling to so easily give up its profits. In this case - unlike with the Moors or Ispania - starting a war would have repercussions with their mother city of Khambayat, and thus with Chandratreya, bringing the consequences closer to home. Thus, after leaving a delegation of troops to found a settlement at Jayagrāhī Varāya - the "Port of Victory" [Porto Alegre] - he returned to the Cape, where he received news that war might soon come to Watyan waters anyway, by way of the Kapudesan cities' conflict with the overweening Musengezi....

On the ground, not as much changed for the inhabitants of Nova Ispania as might be expected. The Captaincy of San Marcos and points west, for instance, continued for now under Ispanian rule, as they had not been visited again since the disastrous naval battle with the Lankan fleet. In the revived Fula kingdoms, their new rulers were nominally Christian and fluent in the local Ispanian creole, while the "Iberios" - the now-plurality of the population that claimed mostly Ispanian descent - remained extremely prominent, and even more so, the Moors. The biggest change was a shift in power from aristocratic governors and bureaucrats generally sent from Ispania, to local land magnates who often had extensive marriage ties to Fula and Tupi clans. These magnates would provide many advisors for the kings of Tatola and Galodugu and, indeed, were just as important as the Fula themselves to their rule. Inland, the herdsman kingdom of Binyaala - which, receiving many escaped slaves, had taken on aspects of a maroon colony - remained just as opposed to colonial expansion, but now Moorish arms held their raids at bay, rather than Ispanian ones.

In Raktahamsabandara, things would not remain so peaceful. Over a dozen years of Ispanian occupation, the Christian minority had built up a rather lot of bad blood with the predominately Hindu inhabitants. After the liberation of the port, vengeful Hindus and Buddhists had looted and burned the Cathedral of St James, and vandalized nearly every other church. The Christians, meanwhile, would answer tit-for-tat, assassinating the Red Swan governor in the middle of the night. It is likely that there would have been a general massacre of the Christians had not the head of the local Mauri merchant interest stepped forward and offered to transport any willing Christians to his family's estates on Isla Pasca [St Helena]. The deputy governor, now no longer a deputy, agreed, and so the majority of the Christians then present in the city would come to leave. The Mauri presence, though, would come to grow, and in time the Christian community in the city became almost as large as before...

Map of the coalitions in 1365 of the War of the Popes, including major Knights naval bases and fortresses. No labels, will likely make a larger version with them once the war shakes out...

Last edited: