You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The Boys In Blue: a New Zealand dictatorship TL

- Thread starter Maeglin

- Start date

Following the 1935 election, New Zealand's conservative parties were in a mess. Led by Coates, the Reform Party had been the party of the rural areas: traditionally interventionist in economics, they were nevertheless deeply hostile to what they saw as the Bolshevism of the Labour Party. Some old holdouts from the Massey era still considered the Liberals (United these days) to be papist types who were insufficiently loyal to the Empire. As for United, the surviving rump of the once progressive and radical Liberal Party found its support in urban areas, among the well-to-do, and laissez-faire businessmen. Money, not Empire, was their creed. A third faction, the Democratic Party, had been created in 1934 by a breakaway group organised by right-wing campaign manager Albert Davy. Davy who had accused the Reform-United Coalition of being "socialistic by inclination, action, and fact," had recruited the former Mayor of Wellington, Thomas Hislop as the new party's leader. Hislop and two other Democrats had won seats at the Coalition's expense.

Almost immediately, feelers for a merger were sent out between the parties: how could they combat Labour if not together? A joint meeting of Reform and United leadership was organised in Wellington for May 1936, to be chaired by recently defeated Prime Minister Forbes. Davy and Hislop, who were not invited, were scathing, and declared that Forbes and Coates had learned nothing from their time in Government.

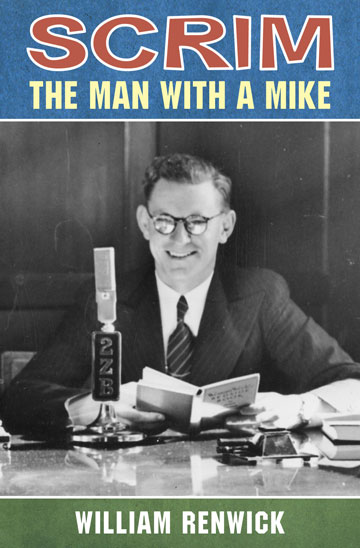

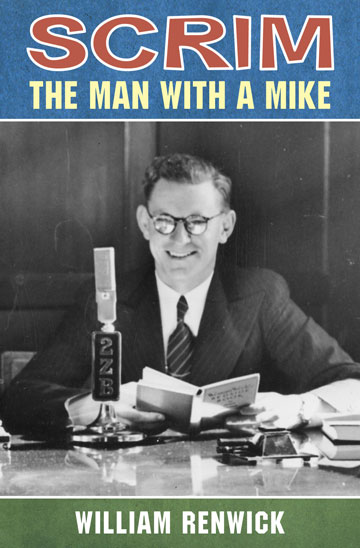

Then, in February 1936, a scandal erupted. A former Post and Telegraph Office official publicly confessed to jamming a 1935 election radio programme by pro-Labour broadcaster Colin Scrimgeour, doing it on the orders of Adam Hamilton, the Coalition's then Minister for Internal Affairs.

Colin Scrimgeour

Hamilton, who had been blamed at the time for this attack on democracy, had nevertheless denied all knowledge of the jamming. Now, having been caught lying, Hamilton was forced to resign his safe seat of Wallace, in rural Southland.

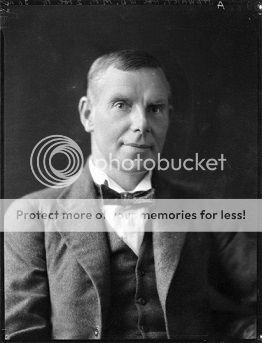

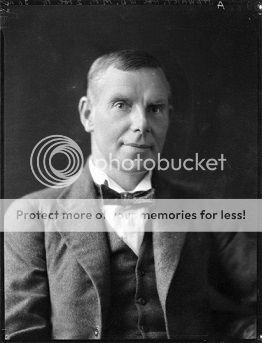

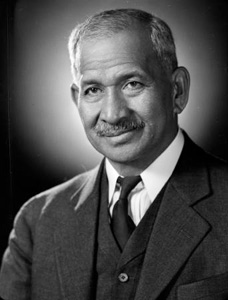

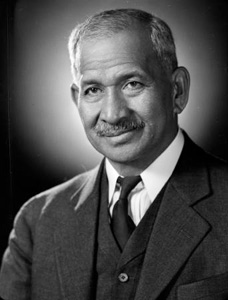

The resulting by-election was won by Reform's former Finance Minister, William Downie Stewart.

William Downie Stewart

Downie Stewart had resigned from the Coalition in 1933 in protest at Coates ramming through a devaluation of the currency. Retaining both his hard money views, and his dislike for the Reform leader, Downie Stewart had stood for a Dunedin seat in 1935, only to find the once strong bastion of imported Scottish Toryism fall to the Labour landslide. The subsequent opening up of an opportunity a few hundred miles to the west seemed a godsend to him.

But what was a godsend to Downie Stewart was a massive headache for Coates. Once in Parliament, his former Finance Minister had rapidly found favour with the laissez-faire Democrats, such that they too arranged a Wellington meeting in order to explore a new party. Even Forbes himself transferred over to the embryonic United Democratic Party, leaving Coates at the May meeting presiding over a half empty room. Uncontested leadership of the newly created National Party did little to cheer Coates, as it seemed obvious that the Opposition had simply played musical chairs with itself.

Gordon Coates

When the dust had settled, National retained 17 MPs, to the United Democratic Party's 10 MPs. As Coates sought to reinvent himself as a pragmatic centrist choice between the far-left of Holland's Labour, and the unreconstructed free-market orthodoxy of the UDP, he wrote in his diary that he wished he could wipe the smug grin from Downie Stewart's face.

Almost immediately, feelers for a merger were sent out between the parties: how could they combat Labour if not together? A joint meeting of Reform and United leadership was organised in Wellington for May 1936, to be chaired by recently defeated Prime Minister Forbes. Davy and Hislop, who were not invited, were scathing, and declared that Forbes and Coates had learned nothing from their time in Government.

Then, in February 1936, a scandal erupted. A former Post and Telegraph Office official publicly confessed to jamming a 1935 election radio programme by pro-Labour broadcaster Colin Scrimgeour, doing it on the orders of Adam Hamilton, the Coalition's then Minister for Internal Affairs.

Colin Scrimgeour

Hamilton, who had been blamed at the time for this attack on democracy, had nevertheless denied all knowledge of the jamming. Now, having been caught lying, Hamilton was forced to resign his safe seat of Wallace, in rural Southland.

The resulting by-election was won by Reform's former Finance Minister, William Downie Stewart.

William Downie Stewart

Downie Stewart had resigned from the Coalition in 1933 in protest at Coates ramming through a devaluation of the currency. Retaining both his hard money views, and his dislike for the Reform leader, Downie Stewart had stood for a Dunedin seat in 1935, only to find the once strong bastion of imported Scottish Toryism fall to the Labour landslide. The subsequent opening up of an opportunity a few hundred miles to the west seemed a godsend to him.

But what was a godsend to Downie Stewart was a massive headache for Coates. Once in Parliament, his former Finance Minister had rapidly found favour with the laissez-faire Democrats, such that they too arranged a Wellington meeting in order to explore a new party. Even Forbes himself transferred over to the embryonic United Democratic Party, leaving Coates at the May meeting presiding over a half empty room. Uncontested leadership of the newly created National Party did little to cheer Coates, as it seemed obvious that the Opposition had simply played musical chairs with itself.

Gordon Coates

When the dust had settled, National retained 17 MPs, to the United Democratic Party's 10 MPs. As Coates sought to reinvent himself as a pragmatic centrist choice between the far-left of Holland's Labour, and the unreconstructed free-market orthodoxy of the UDP, he wrote in his diary that he wished he could wipe the smug grin from Downie Stewart's face.

Last edited:

How would the UK do about this?

Given the response to Lang: withdraw credit, economic blockade, and direct funding of fascists in the form of farmer's sons on horses with guns controlled by an anti-labour paramilitary organised out of the old boys network.

yours,

Sam R.

Meanwhile outside Parliament, the forces of more radical conservatism were on the march. On 8th February, 1933, a Wellington urologist named R.C. Begg had convened a meeting to establish a new organisation: the New Zealand Legion.

R.C. Begg

Begg, comparatively new to politics, was frustrated at what he saw as the fighting and back-stabbing nature of it. He felt that the existing political parties lacked patriotism, and that Government should be reformed in the name of efficiency. He was joined by other figures from the upper and middle classes, who all felt that "something had to be done" about the state of the country, though few of them could agree on exactly what, other than that they ought to be loyal to the King, and that socialism must be fought wherever it appeared.

Begg travelled the country, seeking to drum up support for the movement, and calling for "patriots of the highest order". He found a ready ear among a certain type of person: the white male, who either farmed sheep or worked as a respected urban professional, and who had served as an officer in the Great War. By late 1933, the movement had 20,000 members in a country whose total population was approximately 1.5 million.

But Begg's vague "something must be done" platform was insufficiently organised to last, and printing the group's journal, National Opinion, was a constant drain on funds. As Begg remarked to a friend:

"I certainly didn’t know what I was letting myself in for, when I had the leadership thrust upon me."

By early 1934, the New Zealand Legion seemed in decline, and with the gradual improvement in economic conditions, discontent with the Establishment was starting to wane. Even Begg was openly wondering whether it would be wiser to reinvent as a study group. It was at that point, however, that the Legion found rejuvenation from an unlikely source, when the leader of Australia's New Guard, Eric Campbell, moved to New Zealand, and joined Begg's movement:

Eric Campbell

Campbell had damaged his reputation in Australia through his antics against the Lang Government in New South Wales. Seeking to start afresh in New Zealand, he found the Legion a ready vehicle for his designs. Begg insisted publicly that his group was not fascist, but Campbell's emphasis on "patriotism" over "machine politics", the shared emphasis on loyalty to the crown, and, above all, with the political naivety of Begg, meant that the organisation began swinging ever further towards the fringes of the extreme right.

Begg could not help but feel that his group was starting to get away from him. One Legion member, a certain Sidney Holland (no relation to the Labour leader) was elected to Parliament for Christchurch North under the Reform banner in 1935, and followed Coates into the new National Party.

Sidney Holland

With many of the Legion's meetings being held in secret, Holland was able to juggle respectable Parliamentary politics, while retaining crucial connections with Campbell and friends. Nor was he alone: as the post-1935 Labour Government moved ever further to the Left, it must have crossed many a conservative's mind that the true battle against socialism had to be fought beyond the halls of Parliament. In April 1937, as Paddy Webb took over the mines, and the shipping companies passed into state hands, middle class outrage was such that Campbell was able to talk Begg into funding a short speaking tour of New Zealand by leader of the British Union of Fascists, Oswald Mosley.

Mosley's visit proved to be a divisive affair. Thousands turned out to see him in Auckland, Wellington, Christchurch, and Dunedin, and thousands turned up to protest him. Even many New Zealand Legion members were uncomfortable with the turn of events, and it was at this point that Begg himself departed the scene, returning to the comparative peace of his professional practice. But with the 1938 banking and credit crisis seeming to confirm that the forces of socialism were attacking the very core of New Zealand society, membership spiked beyond even Campbell's dreams. By June 1938, the organisation, which still declined to organise parliamentary candidates, stood at 83,000 members.

R.C. Begg

Begg, comparatively new to politics, was frustrated at what he saw as the fighting and back-stabbing nature of it. He felt that the existing political parties lacked patriotism, and that Government should be reformed in the name of efficiency. He was joined by other figures from the upper and middle classes, who all felt that "something had to be done" about the state of the country, though few of them could agree on exactly what, other than that they ought to be loyal to the King, and that socialism must be fought wherever it appeared.

Begg travelled the country, seeking to drum up support for the movement, and calling for "patriots of the highest order". He found a ready ear among a certain type of person: the white male, who either farmed sheep or worked as a respected urban professional, and who had served as an officer in the Great War. By late 1933, the movement had 20,000 members in a country whose total population was approximately 1.5 million.

But Begg's vague "something must be done" platform was insufficiently organised to last, and printing the group's journal, National Opinion, was a constant drain on funds. As Begg remarked to a friend:

"I certainly didn’t know what I was letting myself in for, when I had the leadership thrust upon me."

By early 1934, the New Zealand Legion seemed in decline, and with the gradual improvement in economic conditions, discontent with the Establishment was starting to wane. Even Begg was openly wondering whether it would be wiser to reinvent as a study group. It was at that point, however, that the Legion found rejuvenation from an unlikely source, when the leader of Australia's New Guard, Eric Campbell, moved to New Zealand, and joined Begg's movement:

Eric Campbell

Campbell had damaged his reputation in Australia through his antics against the Lang Government in New South Wales. Seeking to start afresh in New Zealand, he found the Legion a ready vehicle for his designs. Begg insisted publicly that his group was not fascist, but Campbell's emphasis on "patriotism" over "machine politics", the shared emphasis on loyalty to the crown, and, above all, with the political naivety of Begg, meant that the organisation began swinging ever further towards the fringes of the extreme right.

Begg could not help but feel that his group was starting to get away from him. One Legion member, a certain Sidney Holland (no relation to the Labour leader) was elected to Parliament for Christchurch North under the Reform banner in 1935, and followed Coates into the new National Party.

Sidney Holland

With many of the Legion's meetings being held in secret, Holland was able to juggle respectable Parliamentary politics, while retaining crucial connections with Campbell and friends. Nor was he alone: as the post-1935 Labour Government moved ever further to the Left, it must have crossed many a conservative's mind that the true battle against socialism had to be fought beyond the halls of Parliament. In April 1937, as Paddy Webb took over the mines, and the shipping companies passed into state hands, middle class outrage was such that Campbell was able to talk Begg into funding a short speaking tour of New Zealand by leader of the British Union of Fascists, Oswald Mosley.

Mosley's visit proved to be a divisive affair. Thousands turned out to see him in Auckland, Wellington, Christchurch, and Dunedin, and thousands turned up to protest him. Even many New Zealand Legion members were uncomfortable with the turn of events, and it was at this point that Begg himself departed the scene, returning to the comparative peace of his professional practice. But with the 1938 banking and credit crisis seeming to confirm that the forces of socialism were attacking the very core of New Zealand society, membership spiked beyond even Campbell's dreams. By June 1938, the organisation, which still declined to organise parliamentary candidates, stood at 83,000 members.

Last edited:

Are you going to revive the Protestant Political Association?

Interesting idea. In OTL, the PPA (or what was left of it) actually seems to have backed John A. Lee's Democratic Labour break-away, and they would certainly take him over that Catholic Micky Savage. On the other hand, with Lee in the ascendancy, and Savage's time running out, is there need for Lee to play the sectarian card?

I invoked the NZ Legion because Sid Holland in OTL really was a member of it - it's the easiest way to get the fringe right into a prominent political position, and, of course, Sid Holland isn't going anywhere...

I'll confess I don't know a lot about the ppa but golly, they were big if briefly. Sectarianism is a nasty but powerful reactionary force

By June 1938, the Holland Government had achieved its immediate objectives: a comprehensive social welfare system was in place, Savage had finally seen off the disgruntled medical profession, F.P. Walsh had pushed through compulsory trade unionism and the 40 hour working week, and the Government had brought both the entire financial sector and much of major industry into public ownership. Rex Mason's long-advocated decimalisation of the currency was scheduled for 10th July 1940. Labour had also succeeded in taking control of the Legislative Council, and after Viscount Galway's embarrassing and controversial exit, had managed to get King George VI to appoint Baron Ponsonby as the new Governor-General of New Zealand.

Baron Ponsonby

But it had been a victory achieved at a terrible cost. Divided though they were, the Opposition parties were furious with what they considered to be Labour's attack on individual freedom and liberty. Commercial interests in Australia and the United Kingdom were aghast at the direction of New Zealand, foreign investment had practically dried up, and while the Government's new control of credit enabled it to continue its agenda, there were dark mutterings about "getting Westminster to do something". Had the Chamberlain Government in London not been more immediately interested in dealing with Germany, and had the late 1930s not been practically tailor-made for a New Zealand export boom via high demand for meat and dairy, it is likely that greater pressure would have been applied to the rogue Dominion.

But Holland's own time was running out. Now over 70, and with a history of health issues, on 16th June, 1938 he suffered a debilitating stroke. Lee was out of the country at the time in his capacity as Minister of Foreign Affairs, and would only learn of events when he arrived in London. Cabinet, realising that an election was due in late November, desperately sought an interim leader. Who would it be? Nash had refused to budge from the backbenches, Payne was now too old, Mason did not want it, Walsh was too divisive and had a reputation for overt thuggery, and Savage was both tainted and untrustworthy. Cabinet finally settled on Bob Semple, the Minister for Railways and Public Works.

Robert (Bob) Semple

Semple had an impeccable pedigree of radicalism: blacklisted in an Australian miner's strike in 1903, he had relocated to New Zealand, where he was imprisoned in 1913 for supporting the General Strike, and again in 1916 for opposing the Massey Government's policy of conscription. But, important as "Fighting Bob's" past was to reassuring radicals, he also benefited by being extremely popular with the public. Semple had commissioned reports on establishing electrified rail operations within all the major cities, together with a harbour bridge connecting the Auckland network to the North Shore. Work had already begun in Wellington and Dunedin. Meanwhile, Semple had worked heavily with Lee in getting thousands of state houses built, and had been a savvy enough politician to locate those state houses in marginal seats.

Lee, stranded in London at the time, reportedly consoled himself that Semple was merely interim leader. Meanwhile, he discovered, almost by accident, that the British Establishment was unhappy with events in the Antipodes, when the leader of the British Labour Party, Clement Attlee, told him of the rumours going around the House of Commons. Lee learned that commercial interests had been pressuring the Conservative-dominated National Government to invoke its residual powers and reverse many of the Holland Government's economic policies.

"But can't you stop it?" Lee is reported to have said. "Politically driven intervention on the other side of the world is a bad look for the Government if the Opposition kicks up a fuss."

Attlee shook his head. "There is a lot of money at stake, Jack. And money talks, especially to the Conservative Party."

Lee realised he had little time. He telegrammed Wellington that night, revealing what was intended. He hoped Semple could do something - thank goodness it wasn't Savage, Fraser or Nash on the other end. Heaven only knew what those treacherous dullards would do in these circumstances. Three weeks later, Lee received a telegram from Mason. The New Zealand Parliament had pushed through ratification of the Statute of Westminster 1931 under urgency.

Reading it over morning toast and tea, Lee breathed a sigh of relief, and inwardly thanked the ghost of Ramsay MacDonald and his 1930 Imperial Conference. As he noted later in his diary, MacDonald and Snowden might be burning in Hell for betraying everything the Labour movement stood for, but without that Conference, New Zealand would never have been able to do this. On the other hand, Lee now had a grudge against the Chamberlain Government, and by George was he going to speak his mind before leaving.

Baron Ponsonby

But it had been a victory achieved at a terrible cost. Divided though they were, the Opposition parties were furious with what they considered to be Labour's attack on individual freedom and liberty. Commercial interests in Australia and the United Kingdom were aghast at the direction of New Zealand, foreign investment had practically dried up, and while the Government's new control of credit enabled it to continue its agenda, there were dark mutterings about "getting Westminster to do something". Had the Chamberlain Government in London not been more immediately interested in dealing with Germany, and had the late 1930s not been practically tailor-made for a New Zealand export boom via high demand for meat and dairy, it is likely that greater pressure would have been applied to the rogue Dominion.

But Holland's own time was running out. Now over 70, and with a history of health issues, on 16th June, 1938 he suffered a debilitating stroke. Lee was out of the country at the time in his capacity as Minister of Foreign Affairs, and would only learn of events when he arrived in London. Cabinet, realising that an election was due in late November, desperately sought an interim leader. Who would it be? Nash had refused to budge from the backbenches, Payne was now too old, Mason did not want it, Walsh was too divisive and had a reputation for overt thuggery, and Savage was both tainted and untrustworthy. Cabinet finally settled on Bob Semple, the Minister for Railways and Public Works.

Robert (Bob) Semple

Semple had an impeccable pedigree of radicalism: blacklisted in an Australian miner's strike in 1903, he had relocated to New Zealand, where he was imprisoned in 1913 for supporting the General Strike, and again in 1916 for opposing the Massey Government's policy of conscription. But, important as "Fighting Bob's" past was to reassuring radicals, he also benefited by being extremely popular with the public. Semple had commissioned reports on establishing electrified rail operations within all the major cities, together with a harbour bridge connecting the Auckland network to the North Shore. Work had already begun in Wellington and Dunedin. Meanwhile, Semple had worked heavily with Lee in getting thousands of state houses built, and had been a savvy enough politician to locate those state houses in marginal seats.

Lee, stranded in London at the time, reportedly consoled himself that Semple was merely interim leader. Meanwhile, he discovered, almost by accident, that the British Establishment was unhappy with events in the Antipodes, when the leader of the British Labour Party, Clement Attlee, told him of the rumours going around the House of Commons. Lee learned that commercial interests had been pressuring the Conservative-dominated National Government to invoke its residual powers and reverse many of the Holland Government's economic policies.

"But can't you stop it?" Lee is reported to have said. "Politically driven intervention on the other side of the world is a bad look for the Government if the Opposition kicks up a fuss."

Attlee shook his head. "There is a lot of money at stake, Jack. And money talks, especially to the Conservative Party."

Lee realised he had little time. He telegrammed Wellington that night, revealing what was intended. He hoped Semple could do something - thank goodness it wasn't Savage, Fraser or Nash on the other end. Heaven only knew what those treacherous dullards would do in these circumstances. Three weeks later, Lee received a telegram from Mason. The New Zealand Parliament had pushed through ratification of the Statute of Westminster 1931 under urgency.

Reading it over morning toast and tea, Lee breathed a sigh of relief, and inwardly thanked the ghost of Ramsay MacDonald and his 1930 Imperial Conference. As he noted later in his diary, MacDonald and Snowden might be burning in Hell for betraying everything the Labour movement stood for, but without that Conference, New Zealand would never have been able to do this. On the other hand, Lee now had a grudge against the Chamberlain Government, and by George was he going to speak his mind before leaving.

Last edited:

Harry Holland passed away on 15th September, 1938. It was expected, of course, for he had never regained lucidity after his stroke in June, but that did not make his death any easier for much of the population. Harry had been a somewhat odd figure in the eyes of New Zealanders: whereas Lee was a lightning rod that everyone either cursed or worshipped, and whereas Semple and Savage would be irreversibly associated, for good or ill, with the minutae of their respective ministerial projects, the late Prime Minister had been a man with his eyes on the horizon, a mystic figure who preached decency, socialism, and Christian values, while letting others find the roads to the Promised Land of which he spoke. He had been a poet too, and sales of his Red Roses on the Highways spiked prodigiously over the next few months. Many Labourites and state house tenants kept a copy of it on their bookshelves as a mark of respect. Some of the more radical kept a copy of his Crime of Conscription alongside it, as controversial as that work would later become.

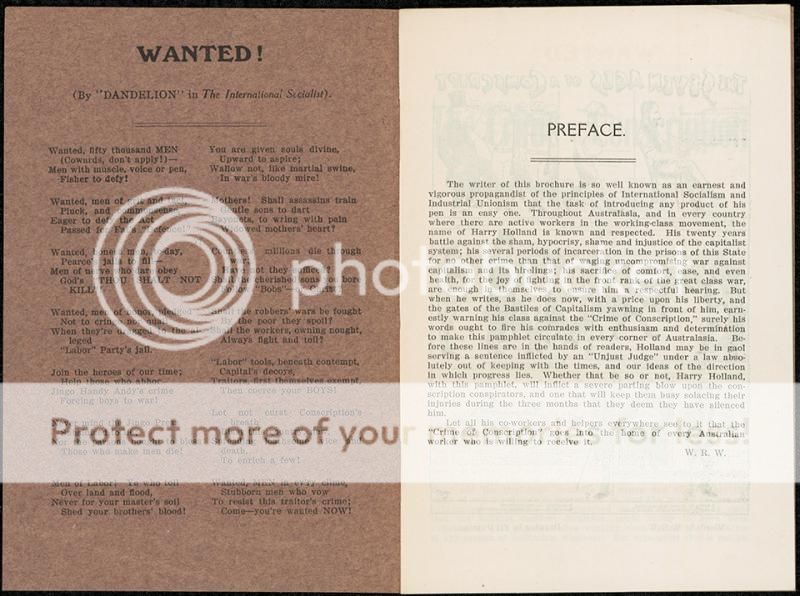

Interior of Crime of Conscription, by Harry Holland

Prime Minister Semple and his Cabinet (minus Lee, who was still in London) mandated a state funeral for the 2nd October, 1938. The service was well attended by political and union dignitaries, including, in a gentle irony, the Australian police officer who had arrested Holland for sedition back in 1909. Also attending were the Australian Prime Minister, Joseph Lyons, who had booked a fast steamer to New Zealand well in advance, and the First Minister of Western Samoa, who had been visiting Auckland on official business. Harry Holland had been deeply critical of New Zealand's colonial treatment of Samoans. He had not only formally apologised to the Samoan people for the Black Saturday massacre of December 1929, but had also taken it upon himself to arrange devolved self-government for Samoa within the state of New Zealand. For that, he had earned the undying affection of Pacific Islanders.

Bob Semple knew his eulogy would be labelled cynical electioneering by the press, but he did not care. There would be an election in less than two months (Semple had mentally pencilled in Saturday, 26th November), which Labour would have to win if Holland's legacy was to survive. He looked across at Coates and Downie Stewart. Both had been authors of untold suffering during the Depression years, and Fighting Bob would be buggered if he was about to let either of them get their hands back on power.

Semple had no sooner left the service that afternoon - he was looking forward to the afterdrinks, hoping like hell Paddy Webb hadn't drunk everything first - only to be pulled aside by an aide from his office.

"Prime Minister?" said the aide.

"What, lad?" said Semple, a bit irritably.

"Telegram from London. Jack Lee's gone crazy, and they're wanting either his head or yours."

Semple read the telegram and ordered the entire Cabinet into a convenient side room. Not that any of them seemed particularly happy. Paddy Webb was complaining about being dragged away from a nice long-legged blonde who had told him she was now divorced, while Micky Savage looked one foot in the grave himself. They seemed even less happy after the Prime Minister told them of the antics of the Minister of Foreign Affairs.

"Jack Lee calls Neville Chamberlain a coward and a traitor?" Mason looked bemused. "He might have a point. Czechoslovakia might be just the first step for Germany. Hell, from what you see in those New Zealand Legion rags, you'd think half of New Zealand would welcome Adolf as liberators."

"That's not the point, Rex," snapped Semple. "Fact is, Jack has caused a diplomatic incident. He did this without consulting me. He did this without consulting anyone. Oh, half the Commons, from Churchill to Attlee, will be secretly cheering him on, but you just don't do that. We have an election to win, and Jack has become a bloody liability. He'll have to go."

Interior of Crime of Conscription, by Harry Holland

Prime Minister Semple and his Cabinet (minus Lee, who was still in London) mandated a state funeral for the 2nd October, 1938. The service was well attended by political and union dignitaries, including, in a gentle irony, the Australian police officer who had arrested Holland for sedition back in 1909. Also attending were the Australian Prime Minister, Joseph Lyons, who had booked a fast steamer to New Zealand well in advance, and the First Minister of Western Samoa, who had been visiting Auckland on official business. Harry Holland had been deeply critical of New Zealand's colonial treatment of Samoans. He had not only formally apologised to the Samoan people for the Black Saturday massacre of December 1929, but had also taken it upon himself to arrange devolved self-government for Samoa within the state of New Zealand. For that, he had earned the undying affection of Pacific Islanders.

Bob Semple knew his eulogy would be labelled cynical electioneering by the press, but he did not care. There would be an election in less than two months (Semple had mentally pencilled in Saturday, 26th November), which Labour would have to win if Holland's legacy was to survive. He looked across at Coates and Downie Stewart. Both had been authors of untold suffering during the Depression years, and Fighting Bob would be buggered if he was about to let either of them get their hands back on power.

Semple had no sooner left the service that afternoon - he was looking forward to the afterdrinks, hoping like hell Paddy Webb hadn't drunk everything first - only to be pulled aside by an aide from his office.

"Prime Minister?" said the aide.

"What, lad?" said Semple, a bit irritably.

"Telegram from London. Jack Lee's gone crazy, and they're wanting either his head or yours."

Semple read the telegram and ordered the entire Cabinet into a convenient side room. Not that any of them seemed particularly happy. Paddy Webb was complaining about being dragged away from a nice long-legged blonde who had told him she was now divorced, while Micky Savage looked one foot in the grave himself. They seemed even less happy after the Prime Minister told them of the antics of the Minister of Foreign Affairs.

"Jack Lee calls Neville Chamberlain a coward and a traitor?" Mason looked bemused. "He might have a point. Czechoslovakia might be just the first step for Germany. Hell, from what you see in those New Zealand Legion rags, you'd think half of New Zealand would welcome Adolf as liberators."

"That's not the point, Rex," snapped Semple. "Fact is, Jack has caused a diplomatic incident. He did this without consulting me. He did this without consulting anyone. Oh, half the Commons, from Churchill to Attlee, will be secretly cheering him on, but you just don't do that. We have an election to win, and Jack has become a bloody liability. He'll have to go."

Last edited:

How about the press and radio broadcasting in TTL New Zealand?

Press is overwhelmingly anti-Labour, as it was in OTL. As for radio broadcasting, we'll get to that...

The 1938 General Election saw rhetoric bordering on the apocalyptic.

"At the last conference of the Federation of Labour the dictum went forth that the next election is to be fought on the issue of ultimate Socialism in New Zealand. Under it, practically the only things the individual citizens would be allowed would be their furniture, their clothing, and their personal effects. If this is what the Government means by ultimate Socialism, we must take up the challenge and fight the election on that issue.

- Gordon Coates, Leader of the New Zealand National Party.

"You will not be allowed to have an opinion of your own. You will think the same as a few so-called revolutionaries. These Socialists are trying to take away what our British forefathers fought so nobly for, the freedom of thought and expression."

- William Downie Stewart, Leader of the United Democratic Party

"The National Party, the UDP, and their friends in the press, don't have the brains of a bloody whitebait between them!"

- Prime Minister Bob Semple, in a speech in Greymouth.

"The General Election tomorrow is a vital test of achievement under Labour as against an unexampled record of impoverishment and stagnation under the Reform-United Coalition - the same parties which parade today as National and the United Democratic Party, flushed with repentance for election purposes, but still unchanged and unchangeable."

- John Payne, Minister of Finance.

"We are not going to have another election fought the same way as this, and I am going to suggest to the Prime Minister next Monday that we establish a chain of daily newspapers... We will make a success of this and give the daily newspapers and vested interests something to think about."

- Michael Joseph Savage, Minister of Health.

"You'll get bored with Bob after a while. He's been giving the same speech for thirty years."

- John A. Lee, returning to New Zealand, having been sacked from cabinet.

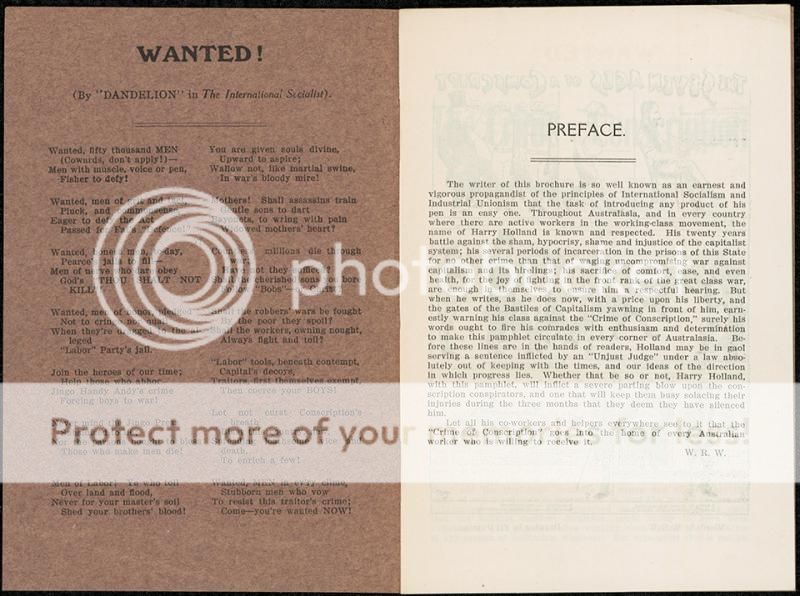

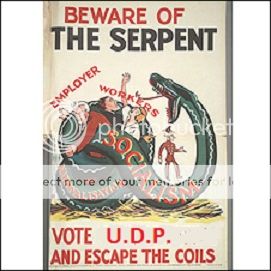

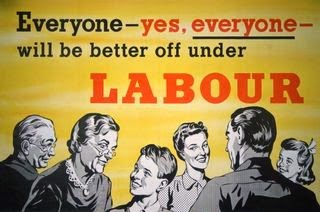

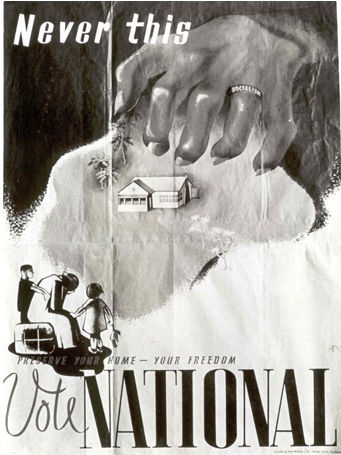

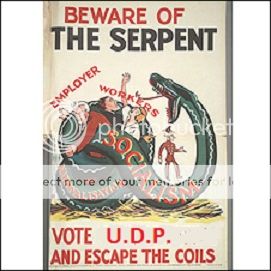

Election posters for the major parties, 1938

On the morning of the election, Saturday, 26th November, 1938, Bob Semple read a copy of the Dominion newspaper over breakfast. His face soured immediately.

"The worst thing," he said to his wife, "is that they actually believe this nonsense. Listen to this in their hysterical editorial:"

"Today you will exercise a free vote because you are under this established British form of government. If the socialist government is returned to power your vote today may be the last free individual vote you will ever be given the opportunity to exercise in New Zealand."

Margaret Semple sighed, and nibbled on a slice of toast. "At least you've got the radio to balance things out. Everyone loves Uncle Scrim."

Colin Scrimgeour had been made controller of the National Commercial Broadcasting Service in 1936. A nice enough chap, but the power had gone to his head: as with all media, he now seemed to consider himself a de facto Member of Parliament, with his demands for policy explanations at all hours.

"If only," said the Prime Minister. "He's spent the entire campaign bleating about how poor Jack Lee ought to be returned to Cabinet. How fascism must be fought tooth and nail. Yes, I suppose it must, but damn the man, we can't let the Old Gang back in. Not with Harry still fresh in the ground."

"Oh well," said Margaret. "You will win today, Bob. You know that."

Semple smiled. "We'll win today, Margaret. Funny thing though, I almost wish I could borrow H.G. Wells' time machine, and go back and tell myself to beware of power. Life was so much simpler without it - back then it was a war between us and them, good and evil - but now when you're tasked with running everything, managing papers, and building post offices - it's so easy to get distracted. If we win, I'll see if I can rehabilitate Walter. He lives for paperwork."

1938 election results

Labour: 41 seats (40% of the vote)

National: 18 seats (28% of the vote)

United Democratic Party: 16 seats (25% of the vote)

Country Party: 1 seat (5% of the vote)

Ratana Maori: 3 seats (1% of the vote)

Independents: 1 seat

Turnout: 92.9% of registered voters.

"At the last conference of the Federation of Labour the dictum went forth that the next election is to be fought on the issue of ultimate Socialism in New Zealand. Under it, practically the only things the individual citizens would be allowed would be their furniture, their clothing, and their personal effects. If this is what the Government means by ultimate Socialism, we must take up the challenge and fight the election on that issue.

- Gordon Coates, Leader of the New Zealand National Party.

"You will not be allowed to have an opinion of your own. You will think the same as a few so-called revolutionaries. These Socialists are trying to take away what our British forefathers fought so nobly for, the freedom of thought and expression."

- William Downie Stewart, Leader of the United Democratic Party

"The National Party, the UDP, and their friends in the press, don't have the brains of a bloody whitebait between them!"

- Prime Minister Bob Semple, in a speech in Greymouth.

"The General Election tomorrow is a vital test of achievement under Labour as against an unexampled record of impoverishment and stagnation under the Reform-United Coalition - the same parties which parade today as National and the United Democratic Party, flushed with repentance for election purposes, but still unchanged and unchangeable."

- John Payne, Minister of Finance.

"We are not going to have another election fought the same way as this, and I am going to suggest to the Prime Minister next Monday that we establish a chain of daily newspapers... We will make a success of this and give the daily newspapers and vested interests something to think about."

- Michael Joseph Savage, Minister of Health.

"You'll get bored with Bob after a while. He's been giving the same speech for thirty years."

- John A. Lee, returning to New Zealand, having been sacked from cabinet.

Election posters for the major parties, 1938

On the morning of the election, Saturday, 26th November, 1938, Bob Semple read a copy of the Dominion newspaper over breakfast. His face soured immediately.

"The worst thing," he said to his wife, "is that they actually believe this nonsense. Listen to this in their hysterical editorial:"

"Today you will exercise a free vote because you are under this established British form of government. If the socialist government is returned to power your vote today may be the last free individual vote you will ever be given the opportunity to exercise in New Zealand."

Margaret Semple sighed, and nibbled on a slice of toast. "At least you've got the radio to balance things out. Everyone loves Uncle Scrim."

Colin Scrimgeour had been made controller of the National Commercial Broadcasting Service in 1936. A nice enough chap, but the power had gone to his head: as with all media, he now seemed to consider himself a de facto Member of Parliament, with his demands for policy explanations at all hours.

"If only," said the Prime Minister. "He's spent the entire campaign bleating about how poor Jack Lee ought to be returned to Cabinet. How fascism must be fought tooth and nail. Yes, I suppose it must, but damn the man, we can't let the Old Gang back in. Not with Harry still fresh in the ground."

"Oh well," said Margaret. "You will win today, Bob. You know that."

Semple smiled. "We'll win today, Margaret. Funny thing though, I almost wish I could borrow H.G. Wells' time machine, and go back and tell myself to beware of power. Life was so much simpler without it - back then it was a war between us and them, good and evil - but now when you're tasked with running everything, managing papers, and building post offices - it's so easy to get distracted. If we win, I'll see if I can rehabilitate Walter. He lives for paperwork."

1938 election results

Labour: 41 seats (40% of the vote)

National: 18 seats (28% of the vote)

United Democratic Party: 16 seats (25% of the vote)

Country Party: 1 seat (5% of the vote)

Ratana Maori: 3 seats (1% of the vote)

Independents: 1 seat

Turnout: 92.9% of registered voters.

Last edited:

How will thes affect WW2?

Not that much. It *will* greatly affect the aftermath of the war at an international level though.

(In OTL, New Zealand Prime Minister Peter Fraser was instrumental in helping set up the United Nations. No Fraser at the San Francisco Conference changes a lot).

Given the response to Lang: withdraw credit, economic blockade, and direct funding of fascists in the form of farmer's sons on horses with guns controlled by an anti-labour paramilitary organised out of the old boys network.

yours,

Sam R.

Just to quickly point out a couple of differences between Lang and what is going on here: whereas New South Wales was a state within a larger federation, New Zealand had been a Dominion in its own right since 1907, so there was no Federal Government to deal with. Also, the economic situation was a lot less desperate in the late 1930s than it had been earlier in the decade.

(But, yes, the fascists and farmers sons on horses are there).

Not that much. It *will* greatly affect the aftermath of the war at an international level though.

(In OTL, New Zealand Prime Minister Peter Fraser was instrumental in helping set up the United Nations. No Fraser at the San Francisco Conference changes a lot).

Now that will be interesting to see the results of.

I'm really curious who will be running the eponymous dictatorship of the title now. Lee and/or other radicals in Labour, or a Legionnaire coup (probably with some level of British support). Or something else entirely?

Now that will be interesting to see the results of.

I'm really curious who will be running the eponymous dictatorship of the title now. Lee and/or other radicals in Labour, or a Legionnaire coup (probably with some level of British support). Or something else entirely?

Keep an eye on Sid Holland.

The election had been a mixed blessing for both Labour and its opponents. On one hand, Semple had presided over the Government's re-election, safeguarding his party's achievements despite mid-term doubts. On the other, Labour's vote and seat total had been cut significantly. Labour now enjoyed a mere 41-39 majority over the other parties combined, and with the Speaker not voting except to break ties, that would become a de facto 40-39 margin. The entire Government could be held hostage by a rogue MP. Worse, with both Lee and Nash now on the backbenches, there were no shortage of potential candidates for Minister of Bloody Troublemakers.

Semple realised that in order to safeguard his Government for the next term, he needed to reach out to three small groupings: the Country Party, with its solitary MP, the lone Independent, Harry Atmore, and the Maori Ratana Movement, who had won three of the four designated Maori seats.

The Country Party was a small but enduring hotbed of rural radicalism - specifically Social Credit-flavoured radicalism. There was nothing they liked better than attacking demonic Auckland money men for making life difficult for small North Island farmers. But while they had been ecstatic when the Government had taken over the hated financial sector, that was both a blessing and a curse for Semple. Would the price of their support be Lee back in cabinet? It would be impossible to juggle both Lee and Nash at the same time... fortunately, the issue did not arise during negotiations. The Country Party would be happy if the Government merely expanded its low-interest loans to farmers, and increased the statutory minimum prices for meat, wool, and dairy.

Harry Atmore

Harry Atmore, on the other hand, really did want Lee back. Atmore, who had represented Nelson as an Independent for nigh on twenty years, was also a supporter of Social Credit. Getting him onside was too high a price, so Semple decided to leave him alone, hoping that the progressive Atmore would be more likely to vote with Labour than the conservative Opposition. As an afterthought, Semple offered Atmore the position of Speaker, but Atmore declined.

"It is more fun to be a player than the referee," he said.

That left Ratana. A Maori Christian movement that had recently spread from the Church to the halls of Parliament, they had generally been supportive of Harry Holland, though they were less enthusiastic about Semple and his often unbiblical language. Semple decided to enlist Savage's help, since the Minister of Health had many friends within Maoridom.

"You have to recognise their grievances, Bob," said Savage. Micky did not look well these days.

"How are their grievances any different from ours?" the Prime Minister asked.

"It's not capitalism they hate, Bob. It's their loss of land, the broken promises, the marginalisation of a once proud people. I'll deal with them..."

Savage was true to his word. The promise of greater efforts to reduce interracial inequality, and consultation on major government public works projects, was enough to get Ratana onside. In fact, the three MPs were willing to not merely support Labour, but actually join it. That left Labour with a comfortable 45-34-1 majority, and Semple now felt safe from a prospective backbench revolt, even after appointing the Speaker. But the thought of the Speakership gave Semple another idea, one that would rub ever more salt into Gordon Coates' gaping wounds.

He decided to approach Sir Apirana Ngata, the National MP for Eastern Maori.

Sir Apirana Ngata

Ngata had become a Liberal MP in 1905, back when they were the great progressive party under Richard "King Dick" Seddon. But whereas most of the old Liberals had defected to Labour, Ngata had stayed, even as his party had rebranded itself as United, and finally merged to form National. He had been a minister in the Depression-era Coalition Government, prior to quitting over a scandal involving alleged favouritism towards Waikato tribes.

"How would you like the position of Speaker, Sir Apirana?"

"A strange offer coming from you, Mr Semple. I seem to recall you suggesting that I was guilty of maladministration, misappropriation of public funds, and betrayal of trust. 'One of the worst specimens of abuse of political power,' I believe were your exact words."

Semple grimaced. This was never going to be easy. "Look, that was four years ago. Things change, Sir Apirana. You've spent over thirty years in Parliament. Few men are better positioned to preside over the House, and surely as an old Liberal, you have nothing in common with the men around you. Why, half of them these days are in bed with the Legion! Do you really think staying with a National Party sliding into racial bigotry and hate will do any favours for your people? Come, be Speaker, and be a part of my Government's new policy of reconciliation. What do you say?"

Ngata thought for a bit, then smiled. "You are too kind, Mr Semple."

News of Ngata's defection was like a punch to the stomach for Coates. It had already been such a frustrating election. The parties of the Right had, between them, polled a staggering 53 percent of the vote, to Labour's mere 40 percent. The public, clearly, wanted to put a stop to this relentless socialism, but the National Party's best efforts had been thwarted by a combination of Downie Stewart's infernal arrogance, and a truly perverse electoral system.

"Perhaps we should take a leaf out of Australia's book, and introduce preferential voting," said Coates to Sidney Holland, the National Party's rising parliamentary star. The two had arranged a quiet meeting in a secluded and high-class Wellington restaurant. "But it beats me why anyone would vote for the UDP over us. We are still the bigger party, we're less constrained by ideology, and I have more experience than that bastard Downie Stewart. I'm a former Prime Minister, for goodness sake. If I can't stop Labour, no-one can."

Sidney Holland, an engineering businessman who was known to all and sundry as 'Sid', held his wine glass up to the light, and seemed to study the pale vintage.

"May I be frank, Gordon?"

"Certainly, Sid."

Holland sipped his wine. "The problem, Gordon, is you."

Coates frowned. "Pardon?"

"When New Zealand thinks of the name Gordon Coates, it thinks of the Depression. It thinks of sugar bag clothes and starvation. No-one wants another Depression, Gordon."

"But Downie Stewart was with us too. In fact, he was more orthodox than me. I wanted to help people! I devalued the currency to help farmers. Downie Stewart was too shortsighted and too inflexible to adapt."

"Downie Stewart quit," said Holland. "He was seen as swimming against the tide - your tide - so probably isn't as hated. But I digress. Downie Stewart can be dealt with, and believe me, I know the people to do it. The simple fact of the matter, Gordon, and I say this with the greatest respect, is that the New Zealand National Party needs a new leader. One not tied to your legacy. One who can reinvent the forces of conservatism."

"But who?" Coates couldn't suppress the whine.

Sidney Holland smiled. "Why me, of course, Gordon. Who else?"

Semple realised that in order to safeguard his Government for the next term, he needed to reach out to three small groupings: the Country Party, with its solitary MP, the lone Independent, Harry Atmore, and the Maori Ratana Movement, who had won three of the four designated Maori seats.

The Country Party was a small but enduring hotbed of rural radicalism - specifically Social Credit-flavoured radicalism. There was nothing they liked better than attacking demonic Auckland money men for making life difficult for small North Island farmers. But while they had been ecstatic when the Government had taken over the hated financial sector, that was both a blessing and a curse for Semple. Would the price of their support be Lee back in cabinet? It would be impossible to juggle both Lee and Nash at the same time... fortunately, the issue did not arise during negotiations. The Country Party would be happy if the Government merely expanded its low-interest loans to farmers, and increased the statutory minimum prices for meat, wool, and dairy.

Harry Atmore

Harry Atmore, on the other hand, really did want Lee back. Atmore, who had represented Nelson as an Independent for nigh on twenty years, was also a supporter of Social Credit. Getting him onside was too high a price, so Semple decided to leave him alone, hoping that the progressive Atmore would be more likely to vote with Labour than the conservative Opposition. As an afterthought, Semple offered Atmore the position of Speaker, but Atmore declined.

"It is more fun to be a player than the referee," he said.

That left Ratana. A Maori Christian movement that had recently spread from the Church to the halls of Parliament, they had generally been supportive of Harry Holland, though they were less enthusiastic about Semple and his often unbiblical language. Semple decided to enlist Savage's help, since the Minister of Health had many friends within Maoridom.

"You have to recognise their grievances, Bob," said Savage. Micky did not look well these days.

"How are their grievances any different from ours?" the Prime Minister asked.

"It's not capitalism they hate, Bob. It's their loss of land, the broken promises, the marginalisation of a once proud people. I'll deal with them..."

Savage was true to his word. The promise of greater efforts to reduce interracial inequality, and consultation on major government public works projects, was enough to get Ratana onside. In fact, the three MPs were willing to not merely support Labour, but actually join it. That left Labour with a comfortable 45-34-1 majority, and Semple now felt safe from a prospective backbench revolt, even after appointing the Speaker. But the thought of the Speakership gave Semple another idea, one that would rub ever more salt into Gordon Coates' gaping wounds.

He decided to approach Sir Apirana Ngata, the National MP for Eastern Maori.

Sir Apirana Ngata

Ngata had become a Liberal MP in 1905, back when they were the great progressive party under Richard "King Dick" Seddon. But whereas most of the old Liberals had defected to Labour, Ngata had stayed, even as his party had rebranded itself as United, and finally merged to form National. He had been a minister in the Depression-era Coalition Government, prior to quitting over a scandal involving alleged favouritism towards Waikato tribes.

"How would you like the position of Speaker, Sir Apirana?"

"A strange offer coming from you, Mr Semple. I seem to recall you suggesting that I was guilty of maladministration, misappropriation of public funds, and betrayal of trust. 'One of the worst specimens of abuse of political power,' I believe were your exact words."

Semple grimaced. This was never going to be easy. "Look, that was four years ago. Things change, Sir Apirana. You've spent over thirty years in Parliament. Few men are better positioned to preside over the House, and surely as an old Liberal, you have nothing in common with the men around you. Why, half of them these days are in bed with the Legion! Do you really think staying with a National Party sliding into racial bigotry and hate will do any favours for your people? Come, be Speaker, and be a part of my Government's new policy of reconciliation. What do you say?"

Ngata thought for a bit, then smiled. "You are too kind, Mr Semple."

News of Ngata's defection was like a punch to the stomach for Coates. It had already been such a frustrating election. The parties of the Right had, between them, polled a staggering 53 percent of the vote, to Labour's mere 40 percent. The public, clearly, wanted to put a stop to this relentless socialism, but the National Party's best efforts had been thwarted by a combination of Downie Stewart's infernal arrogance, and a truly perverse electoral system.

"Perhaps we should take a leaf out of Australia's book, and introduce preferential voting," said Coates to Sidney Holland, the National Party's rising parliamentary star. The two had arranged a quiet meeting in a secluded and high-class Wellington restaurant. "But it beats me why anyone would vote for the UDP over us. We are still the bigger party, we're less constrained by ideology, and I have more experience than that bastard Downie Stewart. I'm a former Prime Minister, for goodness sake. If I can't stop Labour, no-one can."

Sidney Holland, an engineering businessman who was known to all and sundry as 'Sid', held his wine glass up to the light, and seemed to study the pale vintage.

"May I be frank, Gordon?"

"Certainly, Sid."

Holland sipped his wine. "The problem, Gordon, is you."

Coates frowned. "Pardon?"

"When New Zealand thinks of the name Gordon Coates, it thinks of the Depression. It thinks of sugar bag clothes and starvation. No-one wants another Depression, Gordon."

"But Downie Stewart was with us too. In fact, he was more orthodox than me. I wanted to help people! I devalued the currency to help farmers. Downie Stewart was too shortsighted and too inflexible to adapt."

"Downie Stewart quit," said Holland. "He was seen as swimming against the tide - your tide - so probably isn't as hated. But I digress. Downie Stewart can be dealt with, and believe me, I know the people to do it. The simple fact of the matter, Gordon, and I say this with the greatest respect, is that the New Zealand National Party needs a new leader. One not tied to your legacy. One who can reinvent the forces of conservatism."

"But who?" Coates couldn't suppress the whine.

Sidney Holland smiled. "Why me, of course, Gordon. Who else?"

Last edited:

Share: