The Introduction

The Life of Theodemir the Great

Wulfila Strabo [FN1]

Trans. Athelrad Edwardson

London: National University of England Publishing, 1964

Introduction

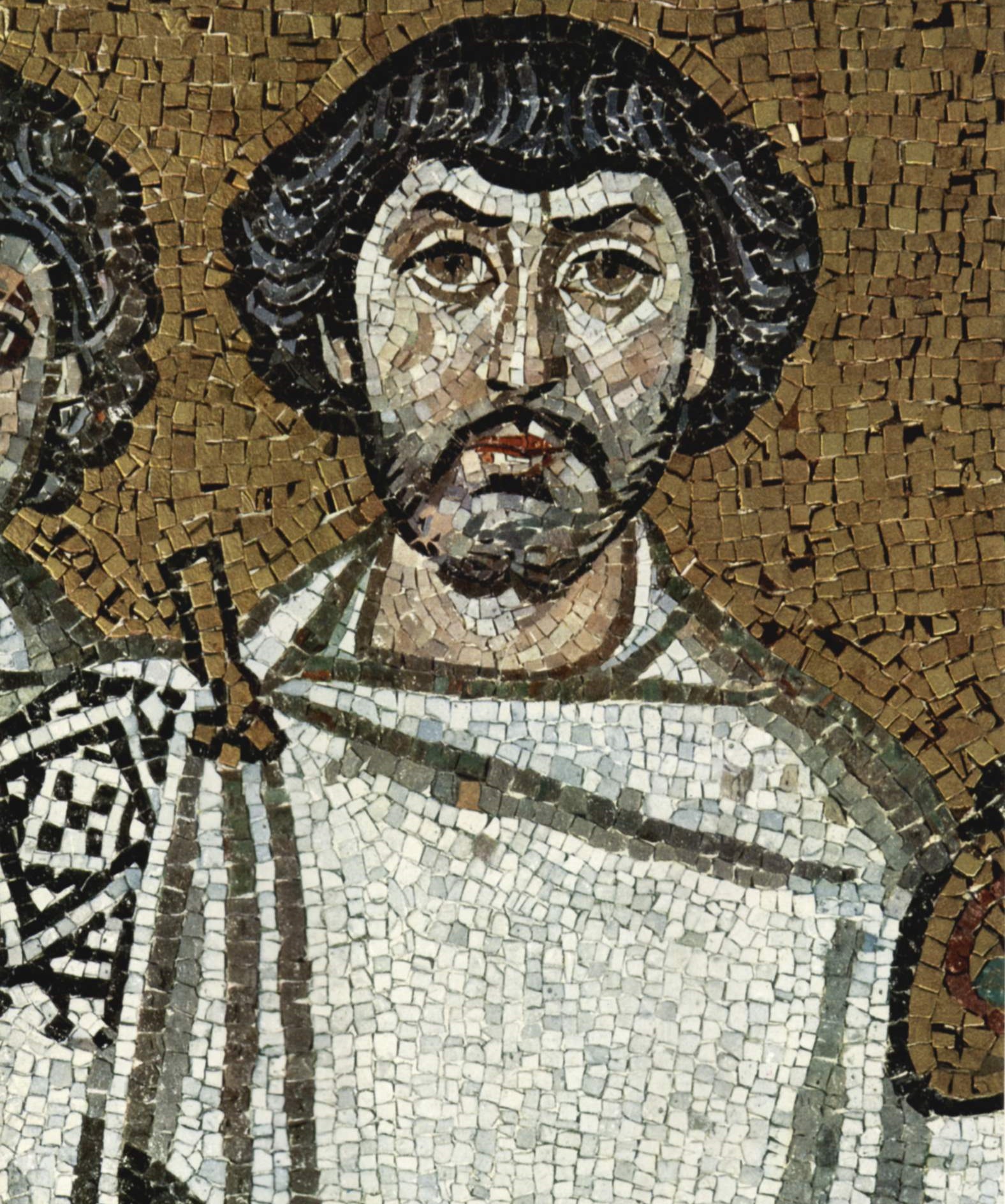

Having once made up my mind to set to parchment the life of my patron and friend, Theodemir the Great, King of the Goths and Emperor of Rome, it became my desire to be as faithful to the man as possible. In the years since his death, a great many legends and myths have emerged, and they do a great disservice to the man. For, that is what he was, and remained through his life. A great man, the greatest since Caesar, I have no doubt, and one of great faith in our heavenly Father, but a man all the same. And so, it shall set down the stories as he told me, as I witnessed, and as I have been told by those who knew him well. In doing so, I do not aspire to reach the levels of eloquence set by the great fathers of literature, for I am but a simple servant and have no desire to promote the name of Wulfila, but only to glorify Theodemir. I pray to God that I am capable of this task, and that no lies, intentional or not, shall fall from my pen.

I am sure that there are many men of leisure and learning who feel that the history of this present age should not be neglected and that the many events which are happening in our own lifetime should not be held unworthy of record and be permitted to sink into silence and oblivion. On the contrary, these men are so filled with a desire for immortality that they prefer, I know, to set out the noble deeds of their contemporaries in writing which may well have no great merit, rather than permit their own name and reputation to disappear from the memory of future generations by writing nothing at all. However, that may be, I have decided that I myself should not refuse to write a book of this kind, for I am very conscious of the fact that no one can describe these events more accurately than I, for I was present when they took place and, as they say, I saw them with my own eyes. What is more, I cannot be absolutely sure that these happenings will in fact ever be described by anyone else. I have there decided that it would be better to record these events myself for the information of posterity, even though there is a chance that they may be repeated in other histories, rather than allow the extraordinary life of this more remarkable emperor, the greatest man of all of those living in his own period, to sink into the shades of oblivion, together with his outstanding achievements, which can scarcely be matched by modern man.

Another reason had occurred to me and this, I think, not an irrational one. Even by itself it would have been sufficient to compel me to write what follows. I mean the care which Theodemir took in my upbringing, and the friendly relations which I enjoyed with him and his children from the moment when I first egan to live at his court. By this friendship he found me to him and made me his debtor both in life and death. I should indeed seem ungrateful, and rightly could be condemned as such, if I so far forgot the benefits he conferred upon me as to pass over in silence the outstanding and most remarkable deeds of a man who was kind to me, suffering him to remain unchronicled and unpraised, just as if he had never lived.

My own meager talent, small and insignificant, nonexistent almost, is no equal to writing this life and setting it out in full. What was needed was the literary skill of a Cicero. But, in his wisdom, God has seen fit to give his servant few of the skills needed for this task. As they say, the lord builds great things from dull tools. I pray, again, that my own meager talents shall be enough to do him justice in my assigned task.

Here then you have a book which perpetuates the memory of the greatest and most distinguished of men. There is nothing to marvel at in it beyond Theodemir’s own deeds, except perhaps the fact that I, not a Roman by birth and a man but little versed in the tongue of the Romans, should have imagined that I could compose anything acceptable and suitable in the style of the Latin histories, and that I should have pushed my impudence so far as to scorn the advice given by Cicero in Book I of the Tusculanae Dispurariones. Speaking about Latin authors, he says that, as you can read for yourself: “For a man to commit his thoughts to writing when he can neither arrange them nor bring any new light to bear upon them, and, indeed, when he has no attraction whatsoever to offer to his reader, is a senseless waste of time, and of paper too.” This distinguished orator’s advice would certainly have deterred me from writing had I not made up m mind to risk being condemned by other men and endanger my own small reputation by setting these matters down, rather than preserve my reputation at the expense of the memory of so famous a man. [FN2]

Book I: The Early Amalings

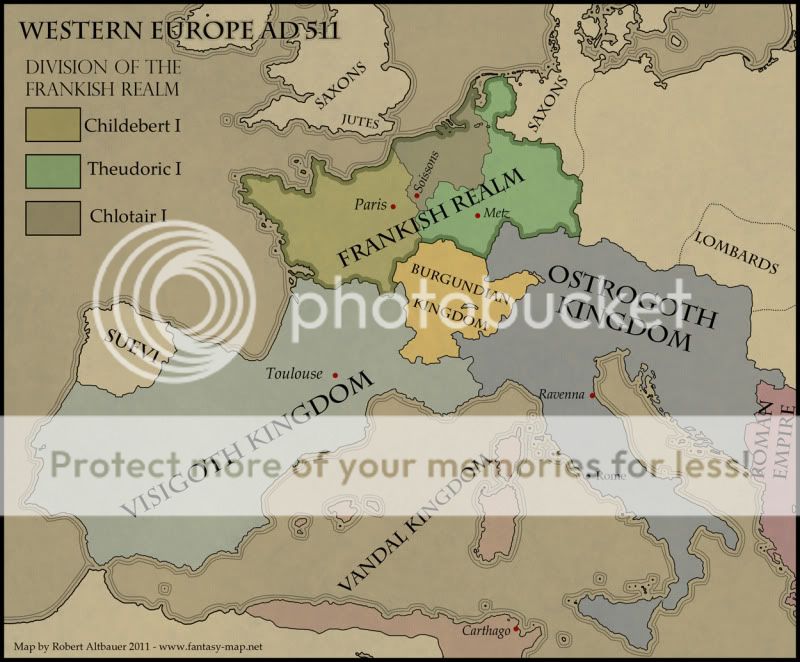

The Amalings, of whom the Goths have long been accustomed to choosing their kings, descended from a great man who earned the name Amala, which means the mighty. It was from the children of Amala that the Gothic people have reached their greatness in power. Following the death of the great Ermanerick, the Goths broke into two. The East Goths, who remained loyal to the Amalings, fell under the sway of the Huns, while the West Goths fled from the plains of their home under the Baltilings and come into the land of the Romans.

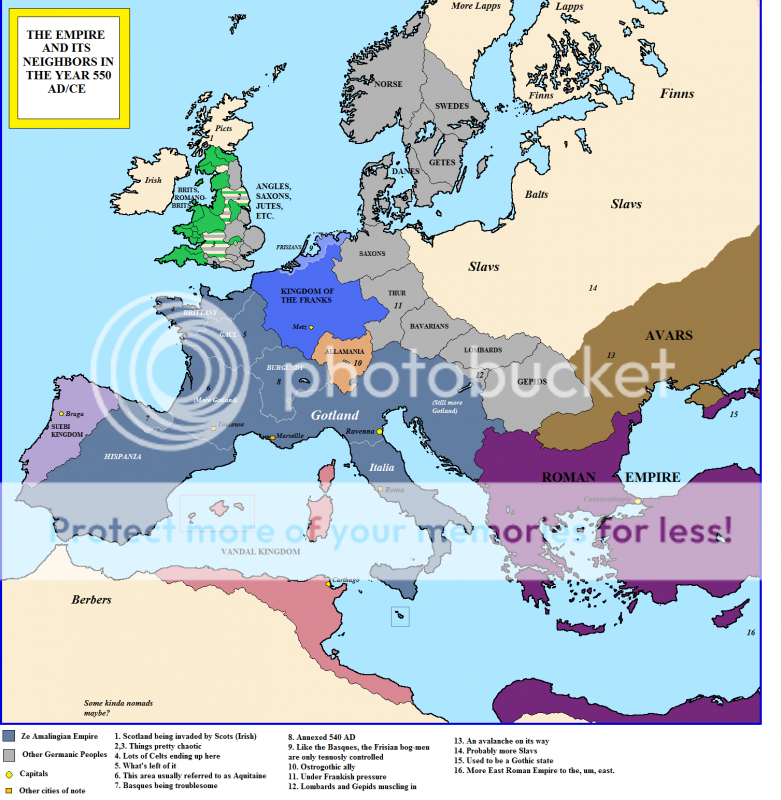

After the death of Attila the Great, and the collapse of the Huns, the Goths under the Amalings continued to prosper on the European plains, beyond the borders of the Romans. It was during this time that Theoderic came to power after the death of his father, Theodemir the First. After nearly twenty years of rule, Theoderic invaded Italy at the request of Zeno, the Roman Emperor of the East. Italy had fallen under the sway of the wicked and vile Odoacer.

Theoderic led the Goths into Italy and quickly subdued the land, agreeing to hold it for the Emperor Zeno. Shortly after, Theoderic married the Queen Audofleda, sister to Clovis of the Franks. It is told that Audofleda had been a pagan before her marriage, but due to his great piety, Theoderic convinced her to see the light of the true faith, and she accepted God and his Son into her life. Because of their faith, God granted Theoderic and Audofleda’s wish, and the queen soon bore the king two children; first Amalsuntha, who deeds and end will be recounted later, and Theodemir who was born 496 years after the birth of our savior, or the year 1249 according to the founding of Rome. Theoderic had an heir, and the people rejoiced.

[FN1] Wulfila the Squinter. Not to be confused with Wulfila the Great, the Arian who converted the Goths to Christianity. Although named after him, they are two very different people.

[FN2] Much of the text of the introduction is taken directly from Einhard's Life of Charlemagne (as translated by Lewis Thorpe), with a few noticable, and important differences.

The Life of Theodemir the Great

Wulfila Strabo [FN1]

Trans. Athelrad Edwardson

London: National University of England Publishing, 1964

Introduction

Having once made up my mind to set to parchment the life of my patron and friend, Theodemir the Great, King of the Goths and Emperor of Rome, it became my desire to be as faithful to the man as possible. In the years since his death, a great many legends and myths have emerged, and they do a great disservice to the man. For, that is what he was, and remained through his life. A great man, the greatest since Caesar, I have no doubt, and one of great faith in our heavenly Father, but a man all the same. And so, it shall set down the stories as he told me, as I witnessed, and as I have been told by those who knew him well. In doing so, I do not aspire to reach the levels of eloquence set by the great fathers of literature, for I am but a simple servant and have no desire to promote the name of Wulfila, but only to glorify Theodemir. I pray to God that I am capable of this task, and that no lies, intentional or not, shall fall from my pen.

I am sure that there are many men of leisure and learning who feel that the history of this present age should not be neglected and that the many events which are happening in our own lifetime should not be held unworthy of record and be permitted to sink into silence and oblivion. On the contrary, these men are so filled with a desire for immortality that they prefer, I know, to set out the noble deeds of their contemporaries in writing which may well have no great merit, rather than permit their own name and reputation to disappear from the memory of future generations by writing nothing at all. However, that may be, I have decided that I myself should not refuse to write a book of this kind, for I am very conscious of the fact that no one can describe these events more accurately than I, for I was present when they took place and, as they say, I saw them with my own eyes. What is more, I cannot be absolutely sure that these happenings will in fact ever be described by anyone else. I have there decided that it would be better to record these events myself for the information of posterity, even though there is a chance that they may be repeated in other histories, rather than allow the extraordinary life of this more remarkable emperor, the greatest man of all of those living in his own period, to sink into the shades of oblivion, together with his outstanding achievements, which can scarcely be matched by modern man.

Another reason had occurred to me and this, I think, not an irrational one. Even by itself it would have been sufficient to compel me to write what follows. I mean the care which Theodemir took in my upbringing, and the friendly relations which I enjoyed with him and his children from the moment when I first egan to live at his court. By this friendship he found me to him and made me his debtor both in life and death. I should indeed seem ungrateful, and rightly could be condemned as such, if I so far forgot the benefits he conferred upon me as to pass over in silence the outstanding and most remarkable deeds of a man who was kind to me, suffering him to remain unchronicled and unpraised, just as if he had never lived.

My own meager talent, small and insignificant, nonexistent almost, is no equal to writing this life and setting it out in full. What was needed was the literary skill of a Cicero. But, in his wisdom, God has seen fit to give his servant few of the skills needed for this task. As they say, the lord builds great things from dull tools. I pray, again, that my own meager talents shall be enough to do him justice in my assigned task.

Here then you have a book which perpetuates the memory of the greatest and most distinguished of men. There is nothing to marvel at in it beyond Theodemir’s own deeds, except perhaps the fact that I, not a Roman by birth and a man but little versed in the tongue of the Romans, should have imagined that I could compose anything acceptable and suitable in the style of the Latin histories, and that I should have pushed my impudence so far as to scorn the advice given by Cicero in Book I of the Tusculanae Dispurariones. Speaking about Latin authors, he says that, as you can read for yourself: “For a man to commit his thoughts to writing when he can neither arrange them nor bring any new light to bear upon them, and, indeed, when he has no attraction whatsoever to offer to his reader, is a senseless waste of time, and of paper too.” This distinguished orator’s advice would certainly have deterred me from writing had I not made up m mind to risk being condemned by other men and endanger my own small reputation by setting these matters down, rather than preserve my reputation at the expense of the memory of so famous a man. [FN2]

Book I: The Early Amalings

The Amalings, of whom the Goths have long been accustomed to choosing their kings, descended from a great man who earned the name Amala, which means the mighty. It was from the children of Amala that the Gothic people have reached their greatness in power. Following the death of the great Ermanerick, the Goths broke into two. The East Goths, who remained loyal to the Amalings, fell under the sway of the Huns, while the West Goths fled from the plains of their home under the Baltilings and come into the land of the Romans.

After the death of Attila the Great, and the collapse of the Huns, the Goths under the Amalings continued to prosper on the European plains, beyond the borders of the Romans. It was during this time that Theoderic came to power after the death of his father, Theodemir the First. After nearly twenty years of rule, Theoderic invaded Italy at the request of Zeno, the Roman Emperor of the East. Italy had fallen under the sway of the wicked and vile Odoacer.

Theoderic led the Goths into Italy and quickly subdued the land, agreeing to hold it for the Emperor Zeno. Shortly after, Theoderic married the Queen Audofleda, sister to Clovis of the Franks. It is told that Audofleda had been a pagan before her marriage, but due to his great piety, Theoderic convinced her to see the light of the true faith, and she accepted God and his Son into her life. Because of their faith, God granted Theoderic and Audofleda’s wish, and the queen soon bore the king two children; first Amalsuntha, who deeds and end will be recounted later, and Theodemir who was born 496 years after the birth of our savior, or the year 1249 according to the founding of Rome. Theoderic had an heir, and the people rejoiced.

[FN1] Wulfila the Squinter. Not to be confused with Wulfila the Great, the Arian who converted the Goths to Christianity. Although named after him, they are two very different people.

[FN2] Much of the text of the introduction is taken directly from Einhard's Life of Charlemagne (as translated by Lewis Thorpe), with a few noticable, and important differences.

![File:Constantinople_imperial_district.png"][FONT=Calibri][SIZE=3][COLOR=](/forum/proxy.php?image=http%3A%2F%2F%5BURL%3D%22http%3A%2F%2Fen.wikipedia.org%2Fwiki%2FFile%3AConstantinople_imperial_district.png%22%5D%5BFONT%3DCalibri%5D%5BSIZE%3D3%5D%5BCOLOR%3D%230000ff%5Dhttp%3A%2F%2Fen.wikipedia.org%2Fwiki%2FFile%3AConstantinople_imperial_district.png%5B%2FCOLOR%5D%5B%2FSIZE%5D%5B%2FFONT%5D%5B%2FURL%5D&hash=e24f1325ad4a8c15039a05fd39345e17)