Dagoth Ur

Banned

APOLLONIDAI OF THE OIKOUMENE

Averting Evil, Fall 31 Meta Seleukos to Spring 31 Meta Seleukos

Averting Evil, Fall 31 Meta Seleukos to Spring 31 Meta Seleukos

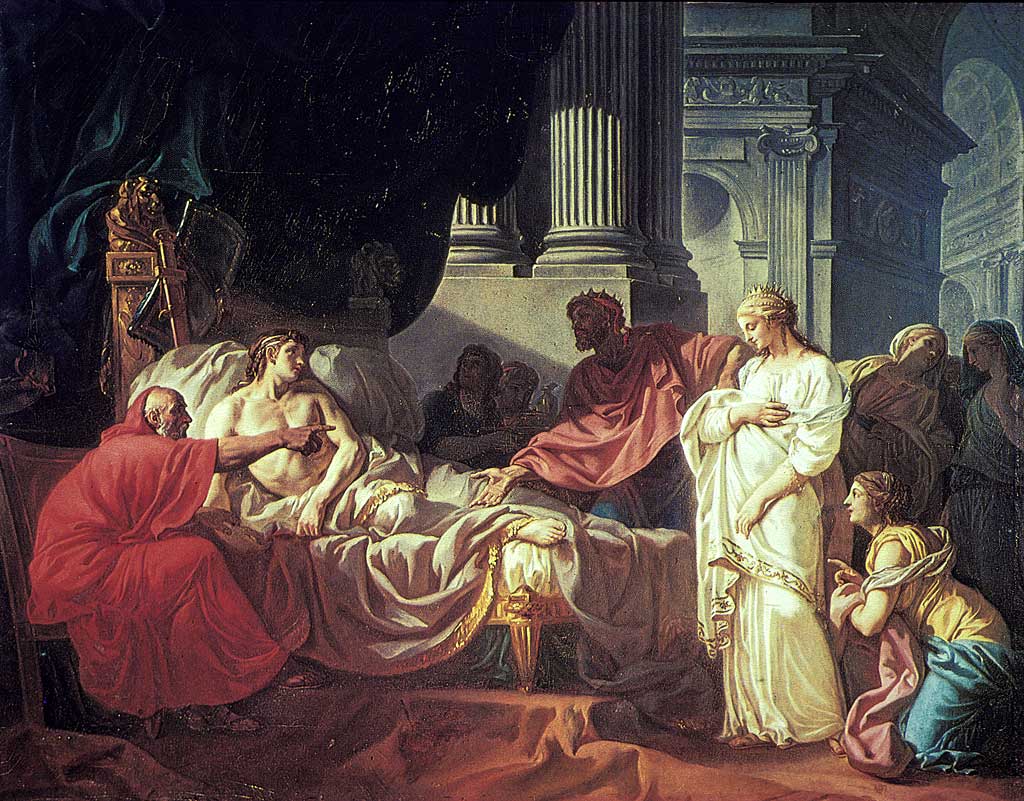

There was a stirring in the room behind him. Demetrios, no novice to guard duty, opened his eyes and stiffened to attention. Out of the corner of his eye he saw Metron across the doorway doing the same. A few moments later the heavy drapes closing off the room were thrust aside by strong brown hands. The man who emerged stood straight, vigorous, stance belying his age. His eyes were lively and bright in a heavily lined face. His hair shone silver around his silk diadem in the dim predawn torchlight. He was gnarled and solid as an oak, and just as immortal if rumor was true. He was their basileus, Seleukos Nikator.

Basileus Seleukos Nikator

He strode forward at once, and Demetrios hopped forward to follow. He cursed Metron under his breath, not for the first time, for his height and long legs. Demetrios was of average height, like their basileus, so he had to keep up with the old man’s energetic pace. Soon they emerged from the arkhon’s mansion, to stand on the terrace surveying the town of Kallipolis below. The basileus stood breathing the fresh morning air, just chill enough to require a light robe for comfort. He seemed to think for a moment.

“What do you think, boys?” he turned to stare at Demetrios and Metron. As always Demetrios found his piercing blue eyes unnerving. “Should I summon the boy to come with me. Or leave him to rest after the excitement yesterday?”

Demetrios remembered the crossing of the Hellespontos yesterday. There was no question of whom he meant. The basileus’s grandson, also named Seleukos, had been running excitedly from one end of their ship to the other marveling at the breadth of the strait and annoying the sailors with all manner of questions. Demetrios was curious to see how the boy would react in the middle of Aigaio Pelagos or Pontos Euxeinos.

Metron spoke first. “Let him rest, sire. We will likely be traveling far today.”

Seleukos looked thoughtful, hand on his shaven chin. Though most of his army now wore beards, he still kept with the discipline of Alexandros. “And you, Demetrios?”

Demetrios smiled shyly, happy his basileus knew his name. What did he think? For a moment he agreed with Metron. Then he looked at the old man. He hated to think the basileus was old, but he was. Young Seleukos would in ten years wish he could trade any amount of sleep for another moment with his grandfather. “I shall wake him, sire. Men wake when they must, rest has little to do with it.” The basileus nodded, and Demetrios turned to jog to the boy’s chamber. [1]

He returned minutes later with the yawning boy and his sour, cursing old paidagogos Nikanor. The beautiful boy, on the cusp of puberty, rubbed his half-lidded eyes and smiled. “Where to, grandfather?”

“To the sacred grove of Athena. Remember my boy, I did not become known as Nikator by neglecting to respect the gods.”

The boy nodded, “Yes, grandfather.” Metron hurried off to find a company of guardsmen. With the sun still a bit below the horizon, the party fell in between the soldiers and left the arkhon’s mansion, then taking a turn along the plain instead of down into the town.

Initially sour, the old paidagogos brightened up at a sudden opportunity to explain something. “Young sire, do you know why there is a sacred grove to Athena here?”

The boy tossed his head. “Athena is one of the greatest Olympians, and deserves respect anywhere. It is not unusual. Is it?”

“Not at all unusual,” Nikanor shook his head. “But think. This area until very recently was always under threat from the savage Thrakian barbarians and not easily accessible by land. Hellenic colonists and traders needed to come by ship. Who would have had the ability to maintain colonies here?”

“Ahhh, I see, so Athenai created these colonies, so in these lands Athena is most revered.”

“Just so,” Nikanor smiled proudly at his charge’s intelligence. Then he went off into one of those long, rambling, bookish tangents of his that Demetrios found sickeningly useless. But he understood that as future basileus, the boy would probably find some benefit from the lectures. Before he knew it their feet had taken them easily down to the beach west of town. There was a green forested area some three stadia square standing out against the yellow farmland and blue sea. The peeking sun bathed the tops of the trees in light.

“Halt!” the basileus called, and the soldiers stopped. Demetrios saw his basileus was frowning, and soon he knew why. They strode to the treeline at the path to the grove, where a slave was holding several horses in the shadows. “You there! Whom do you serve?”

The wide eyed slave bowed and averted his eyes. “Great basileus, I serve Ptolemaios, called Keraunos.”

“A pious one, he?” the basileus scoffed, eyebrow raised. “No doubt he beat me here to pester me about some matter. Or beg me for the throne of Makedonia.” The slave stared at the ground. “No matter,” Seleukos shook his head and made to move on.

“Grandfather,” the boy called. “Let us bring more men.”

“Mmm, what’s that?”

The boy swallowed. “We should bring more men. The man is not called Keraunos [2] for nothing.”

The basileus’s face twisted as if to scoff again, but then he stopped and became still. He looked to the west. “I thank the rising sun, Apollon, for your wisdom my boy.” Louder he said, “Damasias, bring your men and come with us.” The captain hurried along with his dozen men. “The rest of you, surround the grove.”

Thus protected, Seleukos the basileus and Seleukos the grandson entered the sacred grove of Athena.

[1] The POD. In OTL the boy was left to rest

[2] Thunderbolt, and not for being decisive, but rather impatient and destructive

Map of the relevant world in the fall of 31 Meta Seleukos, before Seleukos's crossing to Thraki

News of the apparent plot spread through the army like wildfire. Though the slave at the entrance to the grove had held four horses, eleven men of Keraunos’s retinue, and some of Seleukos’s own officers, had been chased out of the grove. Imprisoned, tortured, and executed, they had revealed the scheme to assassinate the basileus. Donating heavily to the priests of the grove of Athena at Kallipolis, basileus Seleukos also vowed to build a great temple to Apollon Alexikakos, for averting this evil. Scandalized that their basileus could have been harmed on the very eve of total victory, men invented increasingly gruesome ways for Ptolemaios to die.

But it was not to be. Ptolemaios Keraunos, no matter how villainous, was a very useful pawn to use against his half-brother Ptolemaios Beta [1], basileus of Aigyptos. There was no love lost between the two, but there would inevitably be some disaffected segment of the Aigyptian officer and administrative classes who would support Ptolemaios Keraunos as basileus. It also gave Seleukos a good reason to invade Aigyptos, to ostensibly restore an eldest son to his rightful throne. And by doing so eliminate the final great threat to his realm.

The basileus also kept Lysandra and her children under close guard. Lysandra was a full sister of Ptolemaios Keraunos but the two were not close. She had been married to Agathokles, the heir to the diadokhos Lysimakhos, basileus of Thraki and Makedonia. Her half-sister Arsinoe (full sister of Ptolemaios Beta) then married Lysimakhos himself, bred some children with him, and immediately began to intrigue against her stepson and half-brother-in-law Agathokles. If he were removed, Arsinoe’s son’s path to the throne of Thraki would be assured. Eventually Lysimakhos was swayed to his beautiful, intelligent young wife’s way of thinking, and executed his own firstborn son for supposedly intriguing against him. This left Lysandra without a husband and without security, but not without hope. She fled immediately to Asia and sought the help of Seleukos. With her came her Keraunos. He had fled to Thraki years before after being effectively disinherited by his father the great Ptolemaios Soter. However despite his hatred of his half-brother Ptolemaios Beta, Keraunos had seemed reasonably civil, even at times chummy, with his half-sister Arsinoe. Thus suspicions and rumors that he had a hand in Agathokles’s execution, perhaps hoping to seize the throne of Makedonia for himself.

Regardless of the facts, though he joined his sister Lysandra in fleeing to Seleukos there was little love between them. Yet Seleukos kept her and her children under guard. Though her son was a toddler he held a claim to Thraki as did the sons of Arsinoe. And there would be no other basileis of Alexandros’s realm if Seleukos could help it.

When Seleukos reached Lysimakheia alive and well and that city celebrated the fact that it wasn’t being sacked, it was obvious to all that he was going to Makedonia. Home after decades in the trackless, wandering east. Lysimakhos’s priests and some servants had remained at his palace, but his barbarian advisors and other administrators had fled at the news of his defeat and death at the battle of Korou Pedion [2]. As had his family and close friends. His widow Arsinoe and their sons, accompanied by loyal servants, fled to the town of Kassandreia [3] in Makedonia. On hearing of Seleukos’s approach they took ship for Aigyptos knowing that they would be safe and well received at her full brother’s court in Alexandreia.

But it was not to be. News travels quickly across the Aigaio Pelagos. Antigonos Gonatas, pirate-lord of Hellas, doubled his patrols and caught the refugees. The beauty and intelligence of Arsinoe was widely known, she was still young and fertile enough to bear him sons, and most importantly she was one of the most noble women in the world. And she was in his hands.. Thus the 37 year old Antigonos married for the first time, the 35 year old widow Arsinoe at his base at Athenai.

The Lykeion of Athenai brightened for the first time in decades as its skholarkhes [4] Straton of Lampsakenos had been a tutor of Arsinoe and her full siblings in their youth, and had been a correspondent of hers in all the years since. Tall, handsome Antigonos and his forced bride attended weekly debates and demonstrations at the Lykeion, art and knowledge being a pursuit of both. In this way though Arsinoe would have felt more safe in Aigyptos, she attained some degree of comfort. Especially compared to bedding with the octogenarian Lysimakhos.

In this way the two disappointed Seleukos, who had hoped to capture Arsinoe and her sons and keep them very close under heavy guard. Her eldest son Ptolemaios, called Epigonos for becoming the main heir of his father, was a sturdy 18 year old man who could marry and produce troublesome heirs at any time. Thankfully for the time being his stepfather Antigonos was keeping him from escaping to people who would actually care about him, such as his uncle Ptolemaios Beta.

Seleukos adjusted his plans accordingly. He left Lysimakheia and Thraki in the care of Lysimakhos’s timid brother Autodikos, who knew the land and people well. Seleukos himself moved on to Makedonia. It is said that on hiking to the top of the hills north of Thessalonike and seeing the one thousand square milia of the fertile Makedonian plain to the west, Seleukos wept and offered thanks to the gods for bringing him home at last. Fifty-two years after departing Makedonia with Megas Alexandros and his bright-eyed adventurers ready to take on the world, Seleukos was home.

The victor moved on to Pella and took over the stagnant administration of the land, which had been mistreated by its squabbling kings Lysimakhos and Pyrrhos of Apeiros. In appropriate ceremony he was acclaimed basileus of Makedonia by the his army and the assembled Makedonian levies. In the midst of seeing to his homeland, Seleukos continued to think and to write letters. Always thinking of the future, Seleukos plotted to keep Aigyptos busy and unable to interfere with events in Hellas, or to invade Syroi. Magas of Kurenaike was an independently minded man, and chafed at being subordinate to his younger half-brother Ptolemaios Beta; the two men shared the same mother, Berenike, who had married Ptolemaios Soter well after the death of her first husband, Magas’s father. Though Magas owed all to the generosity of his stepfather, he felt no loyalty to the half-brother though their mother was still alive.

So Seleukos offered the hand of his daughter Phila in marriage to Magas, which would keep Ptolemaios Beta too tied up and cautious to interfere in Seleukos’s affairs. Then Seleukos wrote to Antigonos Gonatas himself, as family, to offer him the regency of Makedonia and Hellas in return for submission. There was no doubt in Seleukos’s mind that Antigonos would refuse, and he was correct. To call Antigonos family was almost an insult. After the battle of Ipsos in which Antigonos’s grandfather the great Antigonos Monophthalmos was killed and Antigonos’s father Demetrios was forced to flee, Selekos had married Demetrios’s daughter (Antigonos’s sister) Stratonike to ally himself with Demetrios, still powerful in Hellas and Makedonia, against Ptolemaios in Aigyptos and Lysimakhos in Thraki and Asia.

Seleukos treated Stratonike well and fathered a daughter, the same Phila who would be married to Magas, on her. But on finding that his son Antiokhos, who was older than Stratonike, had fallen in love with her to the point he was sick, Seleukos allowed the two to marry, to save the sanity and possibly life of his son. And Stratonike was in love and very much happy with Antiokhos. But this had been taken very poorly by father Demetrios and brother Antigonos, sharing their daughter/sister like a common whore. Thus the not-so-subtle insult of calling Antigonos family, and thus forcing his rejection of peace. This let all the city-states and petty kingdoms of Hellas, from which Antigonos derived his manpower and wealth, know that it was Antigonos who refused the peaceful path and forced war and destruction on them.

Instead Antigonos wrote hastily to Pyrrhos of Apeiros, busy winning disastrous battles against the Romans in Italia. Pyrrhos was still sour at being forced out of Makedonia by Lysimakhos years earlier, and was taking out his anger on Italians and Karkhedonians [5] alike. Antigonos offered to him his old half of the kingship of Makedonia, if he would come back across the Ionio Pelagos and join Antigonos against the massive eastern threat that was Seleukos.

It took Pyrrhos only a moment to decide. He was tired of his lackluster success, and the ungrateful cities of Megale Hellas were growing stingy with their men and restless against his presence. Pyrrhos agreed forthwith and sealed the deal by agreeing to a marriage between his daughter Olympias and Antigonos’s stepson Ptolemaios Epigonos. Pyrrhos knew how things stood, that Antigonos didn’t quite want his stepson to marry, but that he didn’t dare decline for fear of Arsinoe’s fury. Arsinoe knew this as well, so Pyrrhos would soon be in her, and thus Aigyptos’s, good graces.

Pyrrhos waited for the end of winter, for Ionio Pelagos to stop being so stormy and dangerous. Then he crossed with his army and joined Antigonos at Larisa in Thessalia, ready to do battle.

[1] In OTL later known as Ptolemy II Philadelphus

[2] Better known as Corupedium (curse the Romans and their lack of localization)

[3] Located near modern Nea Poteidaia, north of modern Kassandreia

[4] Director

[5] Carthaginians