Part Five

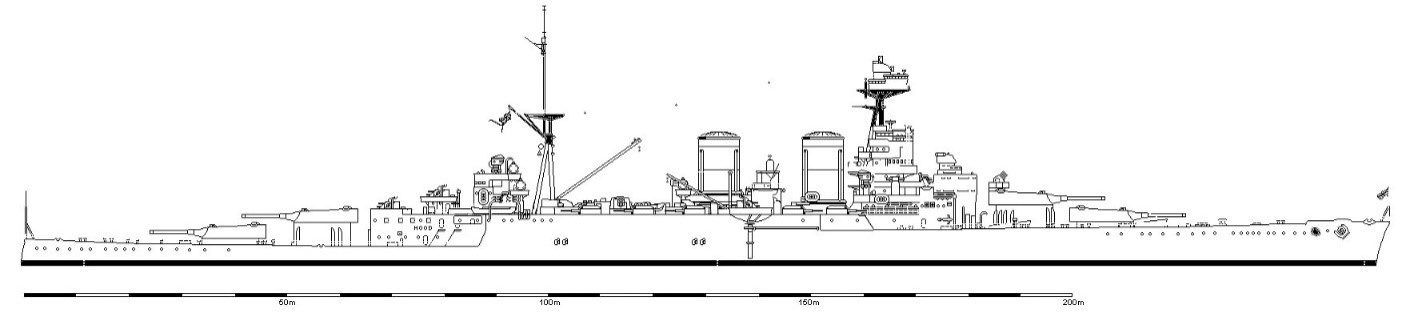

Back at the British force, the carriers were still landing their planes (a process slowed by the now rough seas and increasingly fraught with danger), losing two and their crew in the process, when the aircraft shadowing aircraft reported two heavy ships altering direction. This posed Admiral Holland a problem. With the opposing force now obviously abandoning the push south should he maneuver his force to stay away from the German ships and arrange another strike that day? The carriers, escorted by the cruiser Edinburgh and three destroyers, remained available to conduct further attacks on the German ships, but whether these would be effective given conditions was now doubtful, and if they worsened then there was the danger that contact could be lost. The heavy seas were already limiting the ability of his own four destroyers to keep up and after a brief signal exchange with Tovey over options it was decided for the carriers, with their escorts, would drop back to keep about 80 miles from the Bismarck, while readying a full strike if the conditions improved. His force, the KGV, Prince of Wales, Hood now less than 60 miles from his opponents would intercept the Germans. The carriers would intervene if permitted, although given current conditions this did not appear likely in the short term. It was felt that the opportunity to destroy the German vessels should not be missed and that his force possessed sufficient superiority to finish the job by themselves. He wasn't too concerned about the weather unless it worsened into a full storm.

The three capital ships turned northwest, cutting the corner to the Germans' reported location, and increased speed to 26 knots slowly leaving their struggling escorts behind in the increasingly rough seas. Battle ensigns snapping in the growing westerly wind, and now regularly beginning to ship green water over their bow, they were guided by the plane still shadowing the Bismarck, the two forces were rapidly closing. At just before 1400 Hood sighted smoke ahead on the horizon to the north, confirming the ship's identity at 15nmi (27 km). All British ships involved were already prepared and at action stations, the only thing remaining was to see what the surface action would bring. Holland had been informed by Tovey that the carriers could be ready to launch in about half an hour, but given the deteriorating weather, the situation would wait to depend on the result of the upcoming surface action.

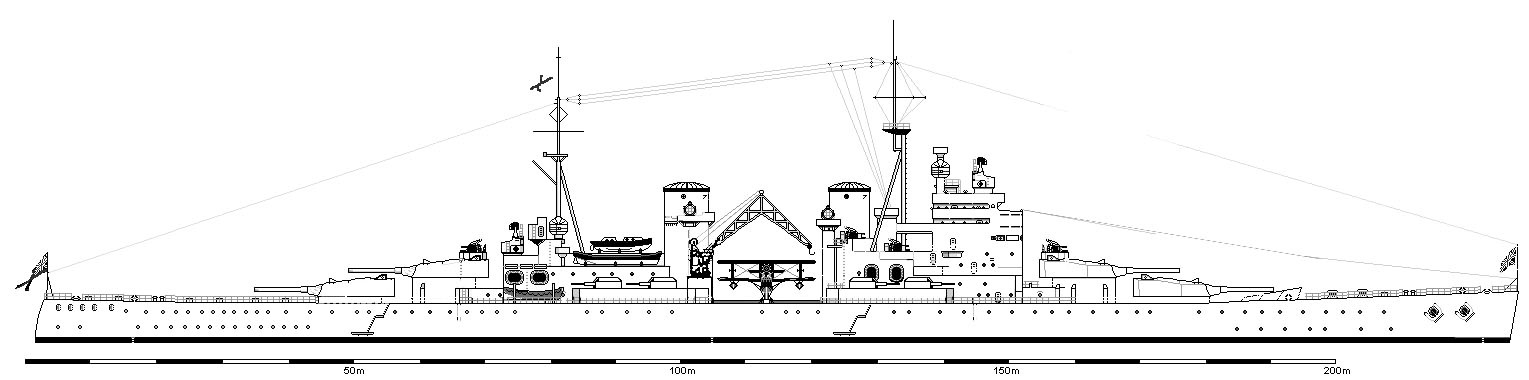

Though unexpected, the German force had been already alerted to the British presence through their hydrophone equipment and picked up the smoke and masts of the British ships 10 minutes later approaching from his stern quarter. The rough seas in the Strait kept the British destroyers' role to a minimum leaving them too far behind the German force to reach the battle. Both groups of ships were in line ahead, Bismarck leading the German Force and Hood the British ships. Increasing speed to 28 knots Holland's tactics as discussed on TBS shortly before the engagement commenced was to close the range rapidly to avoid an engagement where her thin deck protection would make her vulnerable, with the Hood and KGV to concentrate on the Bismarck, whilst POW engaged the Scharnhorst. The seas running from the west, Lutjens increased the forces' speed to 28knots and altered course east to take the seas on his stern and provide a more stable gunnery platform, in effect obliquely crossing the bows of the closing British. Visibility was moderate given the conditions, making things a little difficult for the men manning the optical rangefinders, but the radar sets on both forces were giving him accurate ranges at this stage. A sighting report was sent off and seeing no other option at his point Bismarck opened fire at a range of 24,200m (26,500 yards), with the Hood replying almost immediately.

Holland was a gunnery expert and well aware of the danger posed by

Hood's thinner deck armor, which offered weaker protection despite the post-Jutland modifications, against vertical plunging fire at longer ranges. His decision to reduce the range as quickly as possible dictated that he accepts closing at an angle that placed the German ships forward of his ships, which meant that only half (15 of the 27) British heavy guns could train, matching the full broadside weight of the German force available, and presented the Germans with a bigger target than necessary.

The Germans also had the weather gauge, meaning that the British ships were quartering across the wind, with spray drenching the lenses of the directors and offering a less stable firing platform. Holland had his following ships close to

Hood, conforming to

Hood's movements instead of varying course and speed, which made it easier for the Germans to find the range of both British ships.

The Germans individually engaged their opposite target, and both rapidly gained the range. The Bismarck achieved a straddle on the Hood with its third salvo and gained a hit aft of its funnels which appeared to start a fierce fire with its fourth. At this point, the range had dropped to 10-12nmi (19-22,000m) as Holland was to give his final order to turn to starboard to open the arc of all weapons. At 15:00, just as Hood was commencing the turn Bismarck's fifth salvo hit. Two of the shells landed short, striking the water close to the ship, but at least one of the 38 cm armor-piercing shells struck Hood and penetrated her thin deck armor. This shell appeared to reach Hood's rear magazine detonating 112 t (110 long tons) of ammunition and propellant. The massive explosion broke the back of the ship between the main mast and the rear funnel; the forward section continued to move forward briefly before the in-rushing water caused the bow to rise into the air at a steep angle. The stern also rose as water rushed into the ripped-open compartments. In only eight minutes of firing, Hood had disappeared, taking all but three of her crew of 1,419 men with her. The three survivors would be recovered from a raft by the destroyer Nubian belatedly reaching the scene of the sinking later that afternoon. Though firing eight half-salvos (alternate barrels each turret) and achieving a straddle with the seventh, no hits were achieved by the Hood in the brief exchange before sinking.

The effect of this was to temporarily disorganize the remaining British pair, with the KGV forced to make an emergency swing to port to avoid the sinking wreckage of the Hood, whilst the POW tightened the arc of the original turn to pass the site to starboard. It would be some minutes before both ships steadied down in formation after the shock of this sudden destruction and Captain Wilfred Patterson, commander of the KGV and next senior officer took control of the action. This temporarily affected accuracy and interrupted gunnery before both British ships resumed the exchange. This is not to imply that the British ships had been ineffective at this point. Both had achieved several straddles and registered a single hit on their opponent each. KGV had scored a hit forward of Anton turret and the POW destroyed a secondary mount on the Scharnhorst. But at this point, the action settled down to a two-on-two engagement with the opponents paralleling each other at approximately 11nmi (20,000M). As all this was happening the Scharnhorst was demonstrating a similarly high level of skill, Straddling the KGV with her 4th salvo, before hitting, once with her fifth and twice rapidly with her sixth salvo. With the loss of the Hood, Bismarck now switched targets and commenced to exchange fire with the until now un-engaged POW.

At this point, the battle became a pounding match, one with the German ships now outgunned 14 heavy guns to 19, though the British initially thought that only Bismarck had guns of similar caliber. Aside from armament, the German ships showed the usual ability of a German heavy ship to absorb damage. Many of those involved later would liken this phase of the battle to two dogs in a pit fight, with neither prepared to release its grip once it had sunk its fangs into the other. As for the next 50 minutes, the heavy 15" shells on both sides inflicted an increasing toll of damage as hits mounted. Soon all ships had fires raging and superstructure riddled as the effectiveness of each slowly but steadily was eroded. The first significant impact occurred when a near miss on the Scharnhorst stern exacerbated the existing damage to the propeller forcing it to shut down and reducing the Scharnhorst's speed to 20 knots and Bismarck reduced speed to match. A short time later KGV already ablaze from a previous hit that had struck the hanger abreast the funnel and ignited the aviation fuel present, received a second hit from the Scharnhorst in close proximity which collapsed the forward funnel over the earlier hit and severely restricted the draft for the forward boilers reducing speed to 22 knots and forcing POW to conform. Both sides were also losing combat power. Bismarck's Bruno turret roof was penetrated by a round, killing those inside whilst only effective flash protection prevented the magazine from detonating. Similarly, the Y turret of POW was jammed and inoperative after a hit on the center barrel displaced that gun from its trunnion and dismounted the turret from its ring, killing or injuring the majority of its crew. The engagement seemed to hang in the balance needing only a single crippling hit either way, with the German forces hoping to hold on till the poor light of the early sunset in bad weather offered the chance of breaking contact. Then the final unexpected factor made its unannounced arrival known to both the pre-occupied parties.

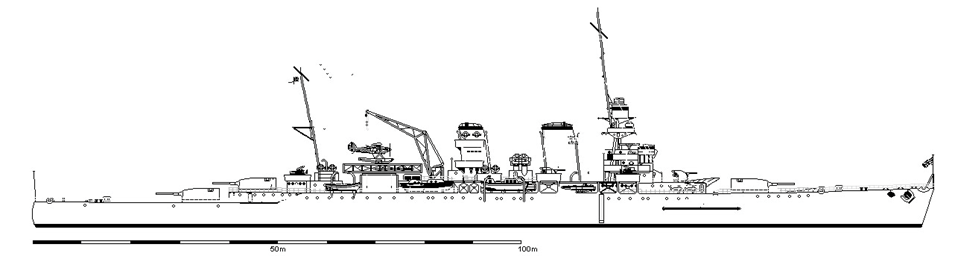

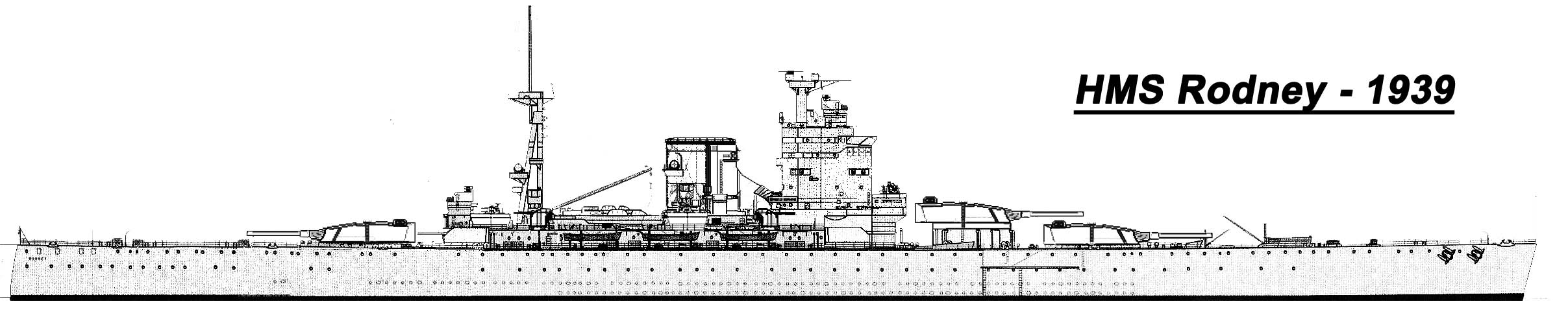

On 22 April 1941,

Rodney which was shortly to transfer to Boston for repairs and a refit was released for transit with two destroyers from Force H. Due to the possibility of a German breakout, her movement was delayed and shifted north to Halifax to be available to cover mid-Atlantic convoy movements if required. After confirmation of the German Force,

Rodney was ordered by the Admiralty to close on that location to participate in the hunt. Closing at her maximum speed of twenty-six knots and despite the risk of running its bunkers dry the Rodney had achieved a position just under the horizon, about 25 nmi (46 km) away as Admiral Holland opened the action. Because of radio silence, neither party was aware of the proximity of Rodney approaching from the south until it opened fire. Cutting corners and risking damage to the engines of the ship the Rodney was able to close to the point of opening fire on the trailing Scharnhorst at 17:12 at a range of 16nmi (26,000m).

The speed of both the engaged forces had by this stage been reduced to about 20 knots due to accumulating damage. The towering shell splashes of Rodney's opening salvo forced realization on Lutjens that the situation had changed again and trying to save what he could was now his only option. Ordering Scharnhorst to disengage north he reversed course in the Bismarck, turning towards KGV and POW to interpose her and cover the withdrawal. Now the target of fire of three capital vessels as the range shortened, Bismarck rapidly began to be struck numerous times, losing Anton and Dora turrets in quick succession. With both her radar and range finders out of action, Caeser turret continued to fire under local control, scoring one final hit on POW By 18:11, all four of

Bismarck's main battery turrets were out of action, allowing KGV and POW to close to around 9,000 yds (8,100 m) with impunity to fire her guns into

Bismarck's riddled and burning superstructure. During this period,

Rodney had swept past these combatants and continued to engage with its forward guns the fleeing Scharnhorst. The two other battleships, having reduced their German opponent to shambles, aflame from stem to stern, ceased fire though the Germans refused to surrender. The ship was settling by the stern due to uncontrolled flooding and had taken on a 20-degree

list to

port by 20:00. By that time, Darkness had largely set in as the belatedly arriving British destroyers closed on the stationary vessel, lit only by the burning wreck. The two British battleships had fired some 700 large-caliber shells at

Bismarck scoring over 40 hits.

At around this time, First Officer Hans Oels, the senior surviving officer, issued the order to abandon ship. With the intercom system broken he sent messengers to confirm the order to abandon as the crew began to appear on the wave-swept deck. Observing this

Garland and

Eskimo closed and began to rescue survivors in severe conditions. It is estimated that around 800 of the Bismarck's, 2000-man crew entered the rough Atlantic waters, and in an astonishing display of seamanship, these two vessels eventually recovered some 311

Bismarck sailors in the fire-lit darkness before finally departing. Having done what, they could and fearing the increased risk of U-boat attack the two destroyers drew off and Garland fired three torpedoes into the stationary vessel's port side. With the superstructure still burning as she submerged,

Bismarck slowly rolled over and disappeared beneath the surface at 21:40.

As this was occurring

Scharnhorst turned north and attempting to escape worked up to 22 knots, but Rodney with the speed advantage swept past the dying fight and steadily closed the distance, engaging with her forward guns. With only her after turret bearing the Scharnhorst still nevertheless continued to display outstanding gunnery and would eventually score three hits on the closing Rodney including one on her bridge which would kill and injure many of the staff, including her captain. Nevertheless, Rodney soon began hitting regularly adding to the already considerable damage to the German ship. At 17:51 one of

Rodney's 15-inch (38cm) shells struck

Scharnhorst's rear gun turret. The shell penetrated the barbette and jammed the turret's training gears, dismounting a barrel and putting it out of action, and made it impossible to effectively engage Rodney whilst trying to escape. At around 18:00, the fatal blow was delivered when another shell struck the ship, passed through the thin upper belt armor, and exploded in the number 1 boiler room. It caused significant damage to the ship's propulsion system and slowed the ship to 8 knots (15 km/h; 9.2 mph). Briefly, the Scharnhorst turned to port to attempt to engage with the sole working forward turret, but a flurry of hits silenced this after just a few inaccurate shots. By 18:55 the Rodney had closed to less than 5nmi and silenced all return fire. In scenes remarkably similar to those playing out to the south, Scharnhorst's superstructure was heavily ablaze and only differed from Bismarck in continuing to erratically maintain way at low speed. With the arrival of the destroyers Tartar and Arunta on the scene, they were ordered to sink the Scharnhorst. Tartar launched two torpedoes, both of which struck, and at 19:45, the ship went down by the bow, with her propellers still slowly turning. British ships began searching for survivors, but after recovering 138 survivors of the crew of 1,968, were ordered away to escort the withdrawal of the Rodney, even though voices could still be heard calling for help from the darkness. This was to mark to end of the surface action phase of the battle. As with Bismarck the Scharnhorst had also received over 40 large caliber hits and both vessels had exhibited remarkable resilience and fought outstandingly to the last against the odds.

Having achieved victory, the British force was now facing its own issues. To arrive at the action, Rodney had run its bunkers down to critical levels and had less than 5% remaining after the battle. This required its immediate detachment to Iceland with an escort. Despite cruising at the minimum speed, it would barely reach the port and upon arriving at Reykjavik would be found to have less than 40 tons remaining, a testament to the long high-speed run undertaken to reach the action. Meanwhile, both KGV and POW had taken over 20 hits each and were severely damaged. Though under power and capable of maneuver and whilst not in danger of sinking, each now had only a single operational turret and no functioning radar. With a slightly better fuel situation but many casualties on board, they had to be released to return to Britain along with the damaged Norfolk, for repairs. This meant Tovey only had the available four carriers (Nieuw Zeeland had by this stage joined up with the Home Fleet Carriers), cruisers Edinborough, Dorsetshire, and their escorts to locate the missing Prinz Eugene. Deploying these as two groups they continued north to try and establish contact with the missing cruiser, heading into increasingly atrocious conditions limiting the carriers' ability to operate aircraft.

While the battleships had been completing the destruction of the Bismarck and Scharnhorst, Prinz Eugen had time to close with the edge of the icepack to use this and its accompanying fickle weather of fog and limited visibility to break contact. Combined with a series of North Atlantic storms that would roll in from the artic, it would enable the cruiser to escape and eventually reach the shelter of air cover from Norway in some five days, despite the efforts of the Home Fleet to prevent this. These vessels' best efforts (five aircraft would eventually be lost conducting search operations) would only briefly locate Prinz Eugene once during a short break in the weather. The hurried strike mounted was badly disrupted by the conditions with most of the aircraft failing to find the target. Only a single flight of eight 500lb bomb-armed Dragonfly's acting in their dive bomber role from Nieuw Zeeland found her and mounted an attack, which would strike the fleeing ship twice. Unfortunately, the resulting damage did not affect the engines or maneuverability of the ship, and contact was again lost as it disappeared into the next storm front. One of the two hits rendered Prinz Eugene rear turrets inoperable but in a cruel twist of fate the second burst in a compartment holding recovered survivors from the Suffolk, killing 30 of them. With no further contact, Prinz Eugen reached the haven of Altenford in Norway on 3 May and her arrival marked the conclusion of Operation Rheinübung.

(One more post to come.)