You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Affiliated States of Boreoamerica thread

- Thread starter False Dmitri

- Start date

Was San Diego economically relevant in the 19th century? I suppose it has an excellent harbor and would be ripe for a trade enclave once California became more stable. But could not Mexico have developed the city on its own?

I had assumed it was ITTL when you mentioned the territory was considered strategic by the Gold War powers in your description.

Based on a quick google search, OTL San Diego only had 500 or so people in 1850, and it didn't surpass 100,000 people until the 1920s.

So yeah, Mexico can certainly develop San Diego (along with LA in Alta/Media California) on its own, but it leads to the question of why would Mexico let go even more of its land ~ especially if that land's filled with loyalist citizens. IMO, this gets even harder once Mexico starts to benefit from all of its many oil wells.

Admittedly, I think it's far more likely more likely for Mexico to keep the parts of California that maintained a Mexican majority while relinquishing claims to those that never had that many homesteaders (the exile kingdoms, etc.).

Still, there are many ways for California and Mexico's relationship to develop. It just depends on how willing or unwilling Mexico is towards ASB/PIC ideas of sovereignty.

You're right, this depends on the overall vision for Mexico. The nationalist attitude toward the Maya could go either way. On the one hand, they were a great civilization. On the other, they live down in marginal jungle country.

From how I'd imagined it, I would say that the Mexico's leadership might try to make a cultural collage of Mexico's Pre-Columbian era groups in order to instill national unity ~ or in other words, invoking TTL's equivalent of the Mayincatec trope.

So while the glories of various Pre-Columbian Mexican groups might be praised, said glories outside an academic setting might be treated as belonging to a singular (and more importantly, united) but still fictional Pre-Columbian ethnic group instead of any distinct ethnic group/nationality such as the Mayans, Aztecs, Olmec, etc. Of course, various minority groups such as the Maya aren't gonna love this treatment of their past, but how they show their disdain for said treatment depends on various factors.

Hope that makes sense.

That said, it's still a part of Russia, and anti-monarchists and other more hardcore nationalists were probably exiled over the years. Russia has no shortage of places to send political exiles, but escaping to California would be a real possibility as well. This is a good idea to hold in reserve if some of the others don't work out.

Interesting! If such a state does come into fruition, it would also be interesting in see the tensions that such a state might have with the PIC ~ Especially if more nationalistic interests in said try to promote the establishment of a free "Old" Ukraine either in the PIC or outside it.

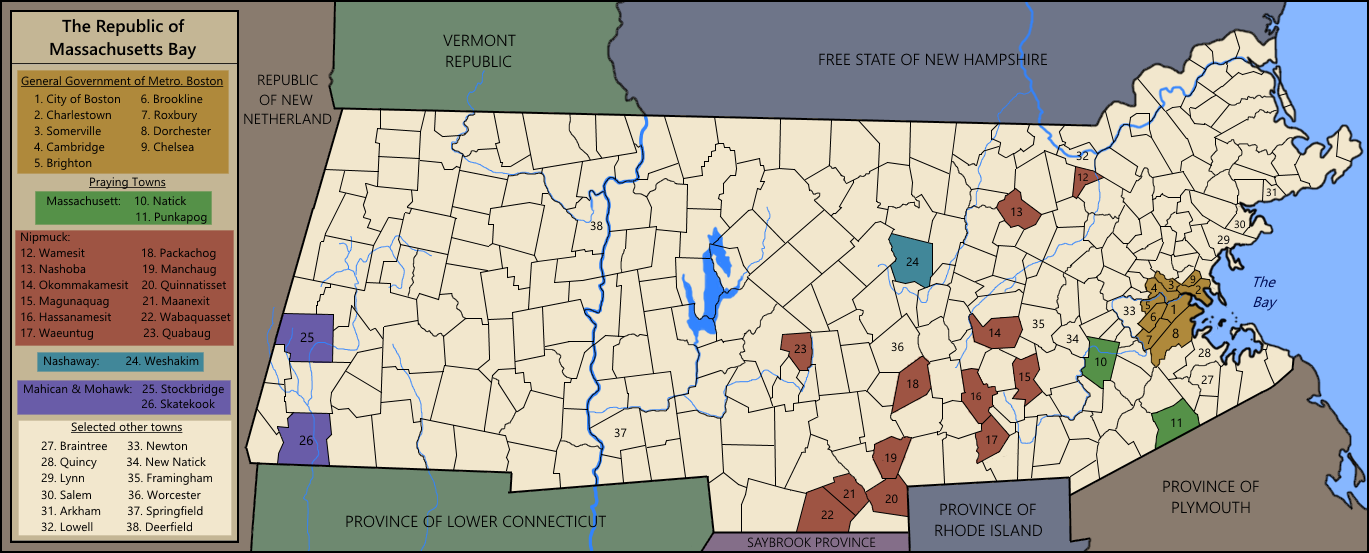

Back to ASB basics: Here's a state map and more state history. It expands on an earlier post.

THE REPUBLIC OF MASSACHUSETTS BAY

HISTORY

Massachusetts Bay was founded by strict Puritans seeking a religious utopia. Their vision was a society of autonomous town-congregations, bodies of devout free men who managed their communities' civic and religious affairs, without distinguishing much between the two. Puritanism dominated the colony into the late 17th century, but a combination of changing religious sensibilities and pressure from England loosened its hold.

By the later 18th century, the colony was a hotbed of liberal religion and political radicalism. Relations between local leaders and England grew increasingly tense as the mother country attempted to impose new regulations and taxes. A complex dispute over import duties on tea led to unrest, then violence, then war. Massachusetts Bay finally declared its independence from England and influenced a number of other colonies to do the same. The Wars of Independence raged up and down the seaboard and west as far as the Great Lakes. Overall they ended inconclusively, with England still in control of several colonies and with much territory remaining in dispute, especially along the Virginia-Carolina border. Massachusetts, however, won definitive and permanent recognition of its independence in the Treaty of the Hague of 1785.

Massachusetts Bay and the other newly independent states made a few attempts to form a new, united republic. Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Vermont, Connecticut, Plymouth, and Rhode Island established the Confederation of New England during the war. Connecticut, Plymouth, and Rhode Island later came under the influence of loyalist governments, left the confederation, and returned to the Empire. Vermont. involved in almost constant disputes with New Hampshire over land, also left and re-joined the confederation several times. There were also attempts to create a wider congress to bring together all of the new Anglophone republics, both north and south; however, these states instead continued to meet with representatives of the loyalist states in what today are called the Anglo-American Congresses. (These meetings, the successors to something like our world's 1754 Albany Congress, had begun well before the Wars of Independence and continued to occur after they ended.) This Congress became more and more a permanent body meeting in Philadelphia, and soon it was also drawing representatives from New Netherland and Iroquoia and their dependencies. Eventually this whole web of alliances became part of the structure of the ASB itself. What was left of the Confederation of New England came to an end.

By the time of independence, Massachusetts, and its capital city of Boston, had already been the economic driver of New England for over a century. The revolution unleashed a new spirit of free-market capitalism. In the first half of the 19th century, Massachusetts Bay became a major world trading power. Its ships crossed the Atlantic and Pacific. The state was an economic force on the west coast, in the South Seas, and as far away as China and Japan. This global reach even turned Massachusetts into an imperial power in its own right. Most prominent was San Francisco, where it established a trading enclave. After the Gold Wars broke out in 1860 this grew into the State of San Francisco, which Massachusetts Bay ruled in condominium with New Netherland until the early twentieth century. SF was Massachusetts Bay's biggest experiment with imperialism, but not its only one. Some Pacific island states are still associated with it and are considered part of the ASB's peripheral territories.

In the second half of the century the state became an industrial power as well. A great wave of European immigrants helped build up the state's factories and cities. Massachusetts led the continent's industrialization; for a time the Boston area was the undisputed heartland of Boreoamerican manufacturing. The economy adapted well, if unevenly, to changing times; the area around the capital remains a leader in such modern sectors as information, education, and hi-tech manufacturing.

LOCAL GOVERNMENT

Like all of New England, the Republic of Massachusetts Bay is divided into towns. New England towns include rural areas as well as population centers and serve as the basic unit of local government. Smaller towns still govern themselves via the direct democracy of the Town Meeting, a legacy straight from puritan days. Larger towns and cities have more typical representative governments.

Boston, the biggest city by far, is a special case. By the late 1800s urbanization had spread well past its municipal boundaries. In our timeline Boston annexed the surrounding towns. In this timeline, the solution was regional cooperation. The towns kept their names and their borders, but most of the machinery of local government was merged into the General Urban Government of Metropolitan Boston... generally, the large agglomeration is usually just called "Boston," while the city proper is termed "City of Boston". Greater Boston expanded to include eight towns besides the City of Boston itself. Their town councils now sit together as a single body, and a single mayor administers the consolidated unit like one city. Since the 1980s or 90s, some power has devolved back to the individual towns in Boston, part of a broad national trend toward more local control. The individual town councils once again meet regularly, though they still spend much more of their time in the full General Council; and each town also now has a Deputy Mayor elected by the community.

The Praying Towns of the 17th century have a special status. They were important vessels of Indian culture in Massachusetts Bay. These were places, where Indian converts to Congregationalism were gathered and closely supervised by English clergymen. While most of the Indian nations in southern New England lost their land, the Praying Towns survived and became an important part of the cultural mix in the colony. Around twenty were founded, mostly in the central part of the state. They allowed their residents a measure of autonomy and dignity in a New England environment that was otherwise incredibly cruel: many other Indians were either driven out of the state, or resettled in what we must call concentration camps on islands in the bay. Most fled for Canada, the Vineyards, or Allegheny, though some converted and joined the Praying Indians. At the time of independence, England concerned itself with the rights of the Praying Indians, and the Treaty of the Hague enshrined their rights.

Over time the Praying Towns shed their puritanical structure, but they kept their autonomy and their communal form of land ownership. Yankee settlers in the west used them as a model for regulating Indian towns in the places where they created new communities: especially in Upper Connecticut, but also in parts of the Upper Country and Ohio where many Yankees settled. Most of the towns are bilingual, with traditional languages under threat from English. The oldest and largest is the mixed English-Massachusett town of Natick, a few miles southwest of Boston.

THE REPUBLIC OF MASSACHUSETTS BAY

HISTORY

Massachusetts Bay was founded by strict Puritans seeking a religious utopia. Their vision was a society of autonomous town-congregations, bodies of devout free men who managed their communities' civic and religious affairs, without distinguishing much between the two. Puritanism dominated the colony into the late 17th century, but a combination of changing religious sensibilities and pressure from England loosened its hold.

By the later 18th century, the colony was a hotbed of liberal religion and political radicalism. Relations between local leaders and England grew increasingly tense as the mother country attempted to impose new regulations and taxes. A complex dispute over import duties on tea led to unrest, then violence, then war. Massachusetts Bay finally declared its independence from England and influenced a number of other colonies to do the same. The Wars of Independence raged up and down the seaboard and west as far as the Great Lakes. Overall they ended inconclusively, with England still in control of several colonies and with much territory remaining in dispute, especially along the Virginia-Carolina border. Massachusetts, however, won definitive and permanent recognition of its independence in the Treaty of the Hague of 1785.

Massachusetts Bay and the other newly independent states made a few attempts to form a new, united republic. Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Vermont, Connecticut, Plymouth, and Rhode Island established the Confederation of New England during the war. Connecticut, Plymouth, and Rhode Island later came under the influence of loyalist governments, left the confederation, and returned to the Empire. Vermont. involved in almost constant disputes with New Hampshire over land, also left and re-joined the confederation several times. There were also attempts to create a wider congress to bring together all of the new Anglophone republics, both north and south; however, these states instead continued to meet with representatives of the loyalist states in what today are called the Anglo-American Congresses. (These meetings, the successors to something like our world's 1754 Albany Congress, had begun well before the Wars of Independence and continued to occur after they ended.) This Congress became more and more a permanent body meeting in Philadelphia, and soon it was also drawing representatives from New Netherland and Iroquoia and their dependencies. Eventually this whole web of alliances became part of the structure of the ASB itself. What was left of the Confederation of New England came to an end.

By the time of independence, Massachusetts, and its capital city of Boston, had already been the economic driver of New England for over a century. The revolution unleashed a new spirit of free-market capitalism. In the first half of the 19th century, Massachusetts Bay became a major world trading power. Its ships crossed the Atlantic and Pacific. The state was an economic force on the west coast, in the South Seas, and as far away as China and Japan. This global reach even turned Massachusetts into an imperial power in its own right. Most prominent was San Francisco, where it established a trading enclave. After the Gold Wars broke out in 1860 this grew into the State of San Francisco, which Massachusetts Bay ruled in condominium with New Netherland until the early twentieth century. SF was Massachusetts Bay's biggest experiment with imperialism, but not its only one. Some Pacific island states are still associated with it and are considered part of the ASB's peripheral territories.

In the second half of the century the state became an industrial power as well. A great wave of European immigrants helped build up the state's factories and cities. Massachusetts led the continent's industrialization; for a time the Boston area was the undisputed heartland of Boreoamerican manufacturing. The economy adapted well, if unevenly, to changing times; the area around the capital remains a leader in such modern sectors as information, education, and hi-tech manufacturing.

LOCAL GOVERNMENT

Like all of New England, the Republic of Massachusetts Bay is divided into towns. New England towns include rural areas as well as population centers and serve as the basic unit of local government. Smaller towns still govern themselves via the direct democracy of the Town Meeting, a legacy straight from puritan days. Larger towns and cities have more typical representative governments.

Boston, the biggest city by far, is a special case. By the late 1800s urbanization had spread well past its municipal boundaries. In our timeline Boston annexed the surrounding towns. In this timeline, the solution was regional cooperation. The towns kept their names and their borders, but most of the machinery of local government was merged into the General Urban Government of Metropolitan Boston... generally, the large agglomeration is usually just called "Boston," while the city proper is termed "City of Boston". Greater Boston expanded to include eight towns besides the City of Boston itself. Their town councils now sit together as a single body, and a single mayor administers the consolidated unit like one city. Since the 1980s or 90s, some power has devolved back to the individual towns in Boston, part of a broad national trend toward more local control. The individual town councils once again meet regularly, though they still spend much more of their time in the full General Council; and each town also now has a Deputy Mayor elected by the community.

The Praying Towns of the 17th century have a special status. They were important vessels of Indian culture in Massachusetts Bay. These were places, where Indian converts to Congregationalism were gathered and closely supervised by English clergymen. While most of the Indian nations in southern New England lost their land, the Praying Towns survived and became an important part of the cultural mix in the colony. Around twenty were founded, mostly in the central part of the state. They allowed their residents a measure of autonomy and dignity in a New England environment that was otherwise incredibly cruel: many other Indians were either driven out of the state, or resettled in what we must call concentration camps on islands in the bay. Most fled for Canada, the Vineyards, or Allegheny, though some converted and joined the Praying Indians. At the time of independence, England concerned itself with the rights of the Praying Indians, and the Treaty of the Hague enshrined their rights.

Over time the Praying Towns shed their puritanical structure, but they kept their autonomy and their communal form of land ownership. Yankee settlers in the west used them as a model for regulating Indian towns in the places where they created new communities: especially in Upper Connecticut, but also in parts of the Upper Country and Ohio where many Yankees settled. Most of the towns are bilingual, with traditional languages under threat from English. The oldest and largest is the mixed English-Massachusett town of Natick, a few miles southwest of Boston.

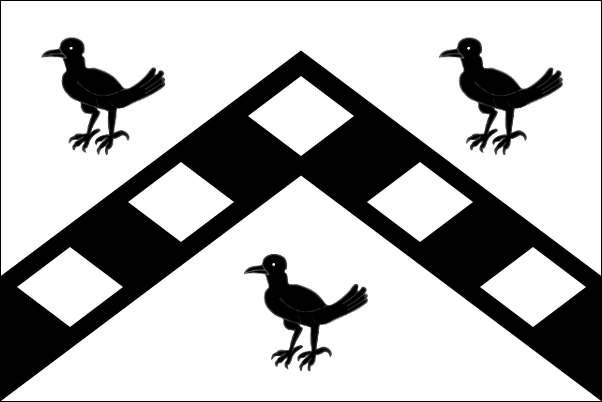

The flag of the Vineyards follows the pattern of using the old proprietor family's coat of arms. Maryland, Pennsylvania, and Saybrook all follow this pattern; they are the states whose early history can be most closely associated with specific proprietors.

Among those, the Penn and Calvert (Maryland) descendants still play a constitutional role in their respective states. Lords Saye and Brooke were absentee landlords of whom no legacy remains but their names. From the 1700s on, the Mayhews of the Vineyards played a diminishing role in the colony's government. They put most of their attention into pastoral care of their Indian congregants. They were sympathetic toward the revolutionaries of Massachusetts Bay and did not object when some islanders left to fight on the mainland. However, English rule fell so lightly on the islands that neither the Governor nor the citizens felt particularly moved toward declaring independence themselves. In the waning years of the Wars of Independence, the governor, the Rev. Caleb Mayhew, resigned and abolished the hereditary governorship. In his place he submitted to the Governor-General of New England a council of three joint governors, two from Martha's Vineyard (one White, one Indian) and one from Nantucket. With a few interruptions, a three-person council has governed the Vineyards ever since.

Among those, the Penn and Calvert (Maryland) descendants still play a constitutional role in their respective states. Lords Saye and Brooke were absentee landlords of whom no legacy remains but their names. From the 1700s on, the Mayhews of the Vineyards played a diminishing role in the colony's government. They put most of their attention into pastoral care of their Indian congregants. They were sympathetic toward the revolutionaries of Massachusetts Bay and did not object when some islanders left to fight on the mainland. However, English rule fell so lightly on the islands that neither the Governor nor the citizens felt particularly moved toward declaring independence themselves. In the waning years of the Wars of Independence, the governor, the Rev. Caleb Mayhew, resigned and abolished the hereditary governorship. In his place he submitted to the Governor-General of New England a council of three joint governors, two from Martha's Vineyard (one White, one Indian) and one from Nantucket. With a few interruptions, a three-person council has governed the Vineyards ever since.

Last edited:

State road sign for The Vineyards.

The Vineyards' system of numbered state roads is pretty adorably small, but it definitely has one; part of being a real state and all that. Single digit roads are on Martha's Vineyard, routes 11, 12 and 13 are on Nantucket.

The Vineyards' system of numbered state roads is pretty adorably small, but it definitely has one; part of being a real state and all that. Single digit roads are on Martha's Vineyard, routes 11, 12 and 13 are on Nantucket.

Last edited:

Yet another sign... The Upper Country uses a simple blue sign to mark its highways. The signs are labeled not with the name of the state but with the Constituent Country they are passing through. Roads are one thing that the Countries have always handled; the state department of transport just coordinates their efforts and helps with funding. Rte. 55 runs north-south, passing through the countries of Miami-du-Lac and Kekionga before entering the State of Ohio.

This gives me an opportunity to briefly describe an additional Country of the PdH that was not on earlier maps: Miami-du-Lac Country.

Centered on the city of Great Miami [*Toledo] and Miami Bay, this country, the Upper Country's smallest, was something of a no-man's-land in the state's earliest history. The French city of Detroit lay to the north, the English of Sanduskey Bay were to the east, and to the south was the rich Mixed society of Kekionga. All three saw the bay as part of their respective areas of influence. Competition for control of the region grew pretty fierce and occasionally violent in the 1820s and 30s. The Judicial Council of Canada, which still functioned as court of last resort for the Upper Country in those days, ruled that the Miami Bay area was not inherently part of any of those three constituent countries and should instead was subject directly to the state government. Great Miami itself later grew into a major city, and it was made the seat of a regional government of its own in 1862. Today the area is largely Franophone due to the influence of Detroit; Miami is of course an important language as well.

This gives me an opportunity to briefly describe an additional Country of the PdH that was not on earlier maps: Miami-du-Lac Country.

Centered on the city of Great Miami [*Toledo] and Miami Bay, this country, the Upper Country's smallest, was something of a no-man's-land in the state's earliest history. The French city of Detroit lay to the north, the English of Sanduskey Bay were to the east, and to the south was the rich Mixed society of Kekionga. All three saw the bay as part of their respective areas of influence. Competition for control of the region grew pretty fierce and occasionally violent in the 1820s and 30s. The Judicial Council of Canada, which still functioned as court of last resort for the Upper Country in those days, ruled that the Miami Bay area was not inherently part of any of those three constituent countries and should instead was subject directly to the state government. Great Miami itself later grew into a major city, and it was made the seat of a regional government of its own in 1862. Today the area is largely Franophone due to the influence of Detroit; Miami is of course an important language as well.

Last edited:

Love the alt-Toledo War! ...even if it wasnt really a war.

Well thank you! I was writing a reply a couple of days ago, and instead expanded it to a longer history:

The Miami War

The Miami War shook the Upper Country in a time when it was still sorting out just what its identity was. The fallout from the English Wars of Independence had brought peace among the continent’s major powers and recognition of the Upper Country as a single unit. The much smaller Kishwauki War (1822-1825) against Illinois defined its borders and clarified the relationship among the Francophone states. But much was left unsettled when it came to the Upper Country’s internal workings. It was not yet completely clear if the Grand Assembly in Detroit was a true government or a mere meeting of allied, self-governing countries. The governor, though chosen by the Assembly, still had to go to Quebec to confirm his position. Much of his power was military as the commander of Fort Detroit. He ruled his local domain of Detroit Country with nearly unchecked power; the old French paternalistic government was still basically in force there. The Miami War revealed the inherent conflict between the governor’s statewide and local roles. It also revealed that the structure of the Upper Country was fragile and inadequate to meet the needs of a growing population.

The conflict grew from the undefined boundaries between the constituent countries of the Pays-d’en-Haut. Sanduskey Country was simply defined as the largely English settlements around the bay and the islands. Did it extend up the shore a little? Who knew? It was not urgent when the population was small, but as the population of English and Mixed people grew and spread, the question became an important one. Likewise, Detroit country certainly included the land around Lake St. Clair and the newer settlements down on Lake Erie, but whether it extended farther was an open question. The lively Mixed town of Kekionga (*Ft. Wayne) was located at the forks of the river Miami-du-Lac and no one was sure how far downriver it extended.

The lower Miami-du-Lac and Miami Bay were thus located between three major clusters of settlements who all had reason to think of the area as their own natural backyard. By the 1820s it was becoming clear that it would be an important crossroads for trade and a big source of income for whoever controlled it. The three adjacent parts of the Upper Country began to compete to be the one that would have it.

So all three areas made moves to get the land. They commissioned traders to build fortified posts at or near the mouth of the river. Militia came in to man the forts. There was no artillery - the separate towns could hardly afford that - but there were plenty of muskets and ammunition, and some of them were used to intimidate or attack the other side. There is no clear date when the “war” began, but parts of the Miami-du-Lac and western Lake Erie were decidedly unsafe by the the 1836 trading season.

The war’s only real offensive came at its climax in the spring of 1838. The key figure was Rémi Taschereau, member of a prominent Canadien family who had had an impressive military career in the Great Lakes. He had become Governor of the Upper Country five years earlier and therefore was also commander at Detroit. He agreed with the Detroit merchants that Miami-du-Lac was important to the town's interests. He also saw the Kekiongans and Sanduskeymen as an affront to his authority as governor. Taschereau resolved to drive them out of the area by force, occupy the Miami-du-Lac area, and use his authority to goad the state assembly into approving the new status quo.

Tashereau’s campaign was preceded by a delegation in the who visited the Kekiongans and Sanduskeymen with official orders to abandon their trading posts. The traders and militia did not quite know what to make of this, since the Upper Country’s governor had never ruled by decree outside of Detroit Country. Soon after came the Detroit Militia in two sloops and several dozen canoes, led by Tashereau. They quickly stormed the blockhouses of their rivals, who mostly fled at the approach of such a large armed force. But the attack had the effect of uniting the other two sides in the three-way rivalry. The Sanduskey militia joined the Kekiongans in paddling upstream to a defensible position at the fork of the Miami-du-Lac and the Glaise Rivers, where there sat an abandoned fort. They quickly dug in, reinforced by new militia companies called up from Kekionga. John Gibbs took command, a soldier of mixed Scottish, French, and Indian origin typical of the Mixed leadership in Kekionga. He enthusiastically re-declared the fort’s old name, Fort Defiance. By the time Taschereau and his men arrived, Gibbs was ready for them. The defenders of the fort threw back the first attack. Taschereau had no choice but to withdraw to the mouth of the river, having occupied the land that was his objective but failed to defeat the rival forces outright.

By then, delegates to the Grand Assembly were gathering in Detroit. Taschereau knew that the assembly could not begin proceedings without him, and he hoped to delay it until he could establish more firmly Detroit’s military control of the Miami-du-Lac. He sent word to his lieutenant, Pierre Jalbert, to send additional men. Most of the delegates in Detroit, however, were outraged at the heavy-handed way that Taschereau was acting. They met outdoors, in front of the fort and the newly built hall of assembly, and began to hold an extralegal session, speaking forcefully against the governor’s actions. Jalbert was unwilling to arrest en masse the leaders of the entire Upper Country, so the delegates continued meeting. The situation in Detroit was so tense, furthermore, that Jalbert feared that if he sent additional men to the Miami-du-Lac, he might lose control of the town entirely. Taschereau raged against his lieutenant’s inaction, but it probably kept the Upper Country from erupting into full-blown rebellion.

The delegates sent an appeal to Canada, whose judicial council still served as the court of last resort for the Upper Country. Canada ordered both Taschereau and Gibbs to stand down and the militia to disband. In a related ruling, they declared that the lower Miami-du-Lac valley was to be neutral territory subject directly to the state government of the Upper Country; the Grand Assembly was left to draw the borders with more specificity. The governor, afraid to return to Detroit, went to Montreal to account for his actions.

The crisis in Miami-du-Lac showed the serious need to reform the Upper Country’s institutions. First and foremost, the city and country of Detroit needed local governments separate from the governorship. Next, the powers of the Grand Assembly to make state laws had to be made clearer. Finally, the powers of militia had to be taken away from the individual towns and regions and made subject to the Upper Country’s civil government. The reforms passed over the next two years helped the Upper Country transform from a frontier alliance into a modern state.

The Miami War actually helped to create a more united Upper Country identity. Earlier it had been feared that largely Anglophone Sanduskey would eventually leave the state and join with Upper Connecticut, and the fact that it had sent no men to the Kishwauki War had fed those fears; but the Miami War confirmed its loyalty to the Pays-d’en-Haut, despite differences in language. Likewise Kekionga, in many ways tied more to the Ohio than to the Great Lakes, earned the sympathy of the lakeshore settlements and solidified its political and social ties to the rest of the state.

The rival trading posts at the mouth of the Miami-du-Lac were consolidated into one, termed Great Miami, which was under the direct authority of the state and the Grand Assembly. The town that took shape around it grew into an important commercial and industrial city, taking its name from the post. In 1862 it became the seat of its own country government, which it remains today.

This is a very quick reference map of the area of the fighting.

Republiek van Nieuw-Nederland? I thought it was Staat, but OK.

Might have been in an earlier version... they modeled the name on the old Netherlands. Does that conflict with anything you did?

Oh, no, nothing contradicts what I've did. I just thought it was Staat.Might have been in an earlier version... they modeled the name on the old Netherlands. Does that conflict with anything you did?

Hello. The map of Massachusetts is interesting but, as a local historian living in the Berkshires, there are a few discrepancies I'd like to point out.

I'm assuming Skatekook is a reference to theSchaghticoketribe. That tribe did not live in Sheffield. Their primary abode was in Stockbridge, where they were later expelled from and relocated to upstate NY. If Sheffield were to remain native, it would be Mahican and called Outhotonnook, under the aegis of Chief Konkapot.

The other portion that this timeline fails to account for is Massachusetts' other territorial claims. At one time the state claimed Maine and portions of Michigan. See this map for a reference: http://www.ohwy.com/history pictures/maps/land-claims.jpg

And while there is a New Netherlands, the western border of MA follows the line demarcated by NY. For many years this border was contested, and a border culture arose known as Oblong. This name persists and is still used in that area today. When it was finally settled, MA lost portions of land along the south, including Boston Corner (now NY) and gained land elsewhere. Other oversights are the Southwick Jog and CT claims on NY. See this map for reference: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/7/76/Ctcolony.png

In your proposed timeline these borders would have likely remained as originally outlined in the colonial surveys, since the later federal government that renegotiated them does not exist.

I hope you find these comments helpful.

I'm assuming Skatekook is a reference to theSchaghticoketribe. That tribe did not live in Sheffield. Their primary abode was in Stockbridge, where they were later expelled from and relocated to upstate NY. If Sheffield were to remain native, it would be Mahican and called Outhotonnook, under the aegis of Chief Konkapot.

The other portion that this timeline fails to account for is Massachusetts' other territorial claims. At one time the state claimed Maine and portions of Michigan. See this map for a reference: http://www.ohwy.com/history pictures/maps/land-claims.jpg

And while there is a New Netherlands, the western border of MA follows the line demarcated by NY. For many years this border was contested, and a border culture arose known as Oblong. This name persists and is still used in that area today. When it was finally settled, MA lost portions of land along the south, including Boston Corner (now NY) and gained land elsewhere. Other oversights are the Southwick Jog and CT claims on NY. See this map for reference: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/7/76/Ctcolony.png

In your proposed timeline these borders would have likely remained as originally outlined in the colonial surveys, since the later federal government that renegotiated them does not exist.

I hope you find these comments helpful.

Hello. The map of Massachusetts is interesting but, as a local historian living in the Berkshires, there are a few discrepancies I'd like to point out.

I'm assuming Skatekook is a reference to theSchaghticoketribe. That tribe did not live in Sheffield. Their primary abode was in Stockbridge, where they were later expelled from and relocated to upstate NY. If Sheffield were to remain native, it would be Mahican and called Outhotonnook, under the aegis of Chief Konkapot.

The other portion that this timeline fails to account for is Massachusetts' other territorial claims. At one time the state claimed Maine and portions of Michigan. See this map for a reference: http://www.ohwy.com/history pictures/maps/land-claims.jpg

And while there is a New Netherlands, the western border of MA follows the line demarcated by NY. For many years this border was contested, and a border culture arose known as Oblong. This name persists and is still used in that area today. When it was finally settled, MA lost portions of land along the south, including Boston Corner (now NY) and gained land elsewhere. Other oversights are the Southwick Jog and CT claims on NY. See this map for reference: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/7/76/Ctcolony.png

In your proposed timeline these borders would have likely remained as originally outlined in the colonial surveys, since the later federal government that renegotiated them does not exist.

I hope you find these comments helpful.

I appreciate that you got an account just to comment on this - feedback is nice.

The Praying Towns and other reservations are based on this page from the Nipmuc Association, in particular the final map, which indicates late-17th century reservations in both Stockbridge and Sheffield. But I'll defer to you, as you know the area. Stockbridge itself was settled in this timeline by a mixed group of Mahicans and Mohawks, which is why I gave it an English name. For consistency it may be better to do the same for Sheffield, since I envision that as a mixed settlement as well. And of course all the Praying Towns attracted plenty of English and other newcomers and have changed a lot in over three centuries. All have a more or less Indian identity, but the degree to which they embody actual Indian culture or genetics varies town to town.

Massachusetts' other lands panned out differently in this timeline. The original Mason-Gorges patent for a colony consisting of New Hampshire and Maine together held; when the Maine portion failed, New Hampshire rather than Massachusetts ended up with the land. No doubt Massachusetts disputed that for years, but this was the final settlement. Add it to the list of reasons that the 1780s-era confederation of New Hampshire, Vermont, and Massachusetts was uncomfortable from the start.

Massachusetts' western claims also certainly existed in this timeline, and with no Treaty of Paris they also included what to us is southern Ontario. All claims in the Great Lakes region were dropped in an 1810s-era treaty whose details I still need to work out... but that treaty set the borders within the region, dividing most of it into Huronia (a direct dependency of Canada) and the Upper Country (at the time a loose federation of autonomous zones with even looser ties to Canada). The interests of English traders and settlers in the Upper Country were protected in the treaty and enforced by congresses of English, French, and Dutch colonials and Indians - the embryonic ASB alliance.

Before renouncing its claim, Massachusetts had one big settlement project on Lake Erie. The towns of Springfield (*Chatham-Kent) and Kettigwyn (*London) in the Upper Country are a legacy of this era. No major Massachusetts settlements were ever established in the Michigan area itself. Massachusetts did not defend its western claims as aggressively as Connecticut; this is my nod to the real history of the Western Reserve. Upper Connecticut survives as a separate state. A land-hungry Connecticut was also important to the history of Poutaxia. But Massachusetts looked to the sea more than to the land for its expansion. (edit) Your comment did prompt me to change my internal map of the Upper Country to make its past connection to Massachusetts more clear. I changed the town's name to Springfield, and I made the region a separate autonomous part of the state, which I've called Ashkany Country. The result is a reversal from the historical situation: the north shore of Lake Erie was mostly settled by republican Yankees, the south shore mostly by Loyalists.

I considered Boston Corner; the border there follows natural features so well that it seemed a logical change that would be made to the border eventually, no matter who was in charge. You can see that the southern border is different at many points. Borders with the separate colonies were negotiated separately. With Connecticut, the compromise border starts at the Southwick jog and then follows a diagonal line north to the Connecticut claim line. With Saybrook, Massachusetts simply got most of what it wanted. The Rhode Island border matches the one in our timeline, and of course Plymouth remains a separate state with its original borders.

As for the Connecticut-NN border, you're right, I have no explanation for that. When I revise the maps I probably should make Connecticut slightly bigger, unless I come up with an explanation for the convergent border.

I hope I addressed most of your concerns, except of course that last one. The ASB is evolving all the time, and part of the goal is learning about some of the unexplored back roads of history; that's where things like Saybrook and the Praying Towns came from.

Last edited:

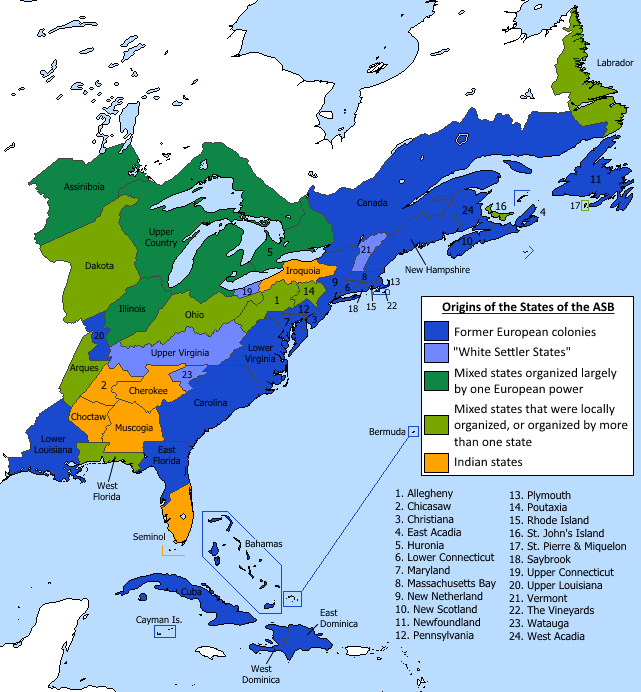

This is a new use of the QBAM as a general locator map. It shows where the different states came from.

Blue states (a majority of the 50) were ruled directly from Europe at one time.

Light blue states were founded by pioneering ex-colonials who crossed the mountains to establish new states of their own.

Dark green states were organized as European spheres of influence with few settlers from the home country. They tend to describe their heritage as indigenous rather than as transplanted from Europe.

Light green states are the most interesting. Most were created within the developing ASB, and indeed you could say that part of the reason the ASB came into being was to manage the affairs of these disputed zones. Others were created as condominiums between two or more states.

Yellow states are Indian polities that became states of the ASB.

Blue states (a majority of the 50) were ruled directly from Europe at one time.

Light blue states were founded by pioneering ex-colonials who crossed the mountains to establish new states of their own.

Dark green states were organized as European spheres of influence with few settlers from the home country. They tend to describe their heritage as indigenous rather than as transplanted from Europe.

Light green states are the most interesting. Most were created within the developing ASB, and indeed you could say that part of the reason the ASB came into being was to manage the affairs of these disputed zones. Others were created as condominiums between two or more states.

Yellow states are Indian polities that became states of the ASB.

Last edited:

The flags that have been created so far for the ASB

(edit) It says "New Sweden" instead of "Christiana"... for some reason that was the name of the file as I saved it. Will fix later.

(edit) Fixed, with some flags added that I had forgotten.

There are 25 flags here, which means half the ASB has officially been flagged!

(edit) It says "New Sweden" instead of "Christiana"... for some reason that was the name of the file as I saved it. Will fix later.

(edit) Fixed, with some flags added that I had forgotten.

There are 25 flags here, which means half the ASB has officially been flagged!

Last edited:

Flag of Assiniboia

What we call the Métis Flag has its origins in the Assiniboia settlements that in TTL became the State of Assiniboia. So its blue version furnishes the state flag. The red version is the war (militia) flag.

Flag of Ohio

Now this is a flag I made for Ohio. I played with other symbols of peace and alliance: fires, calumets, bowls. But nothing looked as good as three white bands suggesting wampum belts, the same symbolism as on the flag of Poutaxia. Green suggests neutrality among the major states (which tend to use a lot of red or blue), and it also represents fertile land and all that.

Writing the history of Ohio took a while, and there are probably still some changes to make. Ohio helped make a lot of ASB history more clear. There are a lot more Actual Dates now than there used to be for the fateful years between 1760 and 1820.

History of Ohio

Peopling the Ohio Country

As a distinct region, Ohio’s history goes back to the middle of the 17th century and the era of the fierce Iroquois attacks against seemingly everyone living west of their homeland. Sparked by competition over the fur trade and sustained by the need to avenge and recoup losses through the abduction of enemies, the wars lasted twenty years and ranged all over the Ohio country and Great Lakes. When the dust settled, Ohio was almost totally emptied, its inhabitants having relocated to refugee settlements in the Upper Country - or been carried off to Iroquoia. The Iroquois became the de facto rulers of the vacant land, using it mainly as a hunting ground. They claimed in their dealings with Europeans to be its rulers by right of conquest.

New groups began to arrive in Ohio after 1700. Empty land meant new opportunities, especially for young leaders from outside the traditional power structures of tribe and empire. Many Huron-Petun people left Huronia and established the Wyandot tribe during this era; similarly, many Iroquois left their people to found the tribe known as the Mingo. Members of existing tribes, in particular the Lenape, Miami and Shawnee, also came and established themselves during these decades, while others came from southern peoples such as the Cherokee. These disparate people gathered together in villages that lacked any clear ethnic identity, often under charismatic leaders, many of Métis background. By the 1740s a number of small republics had cropped up in the region. One lay along the White River in the center and west of the Ohio country; another dominated the Forks of the Ohio. The republics were troublesome to all the established powers of the continent. They rejected alliance with any empire and pursued an independent course.

Imperial competition was on the rise. Dutch and some English traders were coming west in greater numbers in search of furs. This challenged the power of France: the Iroquois may have considered Ohio to be their own hinterland, but the French felt the same way about it. Now they had to build up their presence to resist the challenge from their rivals. Early French settlements included Ouiatenon and Vincennes, both on the Wabash. These were somewhat awkwardly placed within the French empire. Though founded by Canada, these posts were along rivers with easy access to Louisiana. So Louisiana and Canada, the two centers of French power, soon found themselves in a rivalry of their own. Commanders of the forts, though chosen by Canada, generally also had to be acceptable to officials in Louisiana. The actual habitants around the forts eventually were largely Métis, with both French and indigenous backgrounds. Like the leaders of the republics, these habitants began the process of building a separate, independent identity in the Ohio country. Not to be ignored is the small but not insignificant population of slaves, former slaves, and free children of slaves, all of them forming a part of the community of the French settlements.

English settlers came a little later. Once the Crown gave its approval to Virginian settlement past the mountains, a trickle of people began moving west intent on agricultural settlement. They entered the complex society of Ohio with help from allied Indian groups, especially Cherokee, who accompanied them and built new villages not far from the new English centers. Settlement was managed by a few land companies, but at this point these companies engaged more in speculation than actual settlement. The English pioneers built villages that were largely self-sufficient and cut off from Virginia itself. For most of the 18th century the English population mostly stayed south of the river in what today is Upper Virginia.

So by the late 18th century, Ohio was a dynamic region of bewildering human diversity. It was a place where competing imperial ambitions contrasted with emerging local cultures wanting to govern themselves.

Wars of empire and revenge

Ohio was also a place of violence. With no clear authority and lots of rival factions, it did not take much for disputes to lead to feuds and feuds to wars. An example is the Fox War of the 1740s. It began in Detroit but spread to consume the Ohio and Illinois countries. Fought between the Fox tribe and the French alliance of the Upper Country, it had no real economic cause, but arose from ethnic conflict and perceived slights. The cycle of revenge lasted for years until it was finally spent, and the Fox were driven west of Lake Michigan.

Imperial wars also made themselves felt in Ohio. The eighteenth century in this timeline was not quite as polarized as our own: England and France were rivals, certainly, but their wars were not quite so numerous, and their colonists had less of a sense of being locked in an eternal fight to the death. And anyway, as in our timeline, imperial wars influenced politics and fighting in Ohio, but they did not drive it directly. England and France could fight in Europe while life in Ohio continued almost like normal, and by the same token fighting in Ohio could break out between the colonists or their allies even as the kings in Europe were trying to get along. And all the while, republics, neutral tribes, and traders did their best to avoid the imperial conflicts, or use them to their advantage.

The Wars of Independence in the English colonies shook Ohio far more. When the Anglo-American world shattered, new rivalries appeared that made themselves felt in the west. Several of the colonies had had claims in Ohio that they had not tried hard to enforce before, but now that land seemed much more important. In 1772 Virginia sent an expedition of militia down the river, building blockhouses and crude forts all along the way. This had the effect of angering the French in their small forts; so while the French in Canada eagerly supported revolutionaries in the north, Virginia got little sympathy from the French in Louisiana. But the blockhouses became the seeds of a new generation of settlements; by 1800 Virginia thoroughly dominated the land south of the river. Revolutionary Connecticut, too, sent an expedition to seize Fort Sanduskey, the most important English post on Lake Erie. Though they seized the fort, the English troops crossed the bay and dug in to new positions.

Alliances extended the fighting to a wider area. The Iroquois themselves stayed out of the Wars of Independence, trying to stay on friendly terms with both sides. They signed an accord with Virginia ceding to them their claim to much of Upper Virginia, and they kept up trade with Crown posts. But other groups did take sides. The Connecticuter force that attacked Sanduskey was in fact more than half Indian or Mixed, recruited from settlements on the Cuyahoga. The defenders included a large force of Miamis. A delegation of Virginians and allies to the White River republic turned violent when the leaders there refused to give their support to the newly independent state; the militia attacked the village and ultimately were forced to retreat back to their base on the Ohio River. At Ouiatenon, fighting between pro-republican and pro-loyalist Indians grew heated. Following orders from Quebec, the commander let the republican sympathizers into the fort and closed the gate, but he did not let them onto the ramparts to attack their foes. They left after a few days; Ouiatenon itself was spared of further violence, but skirmishes continued in the countryside.

The peace after independence

The Wars of Independence drifted to a halt rather than build to a climax. In the south they degenerated into skirmishes and petty violence along the Virginian-Carolian border, while in the north the English shored up their support in southern New England and relied on diplomacy and politics to lure other states back into the fold. The real coup was in Connecticut, which elected a loyalist majority to its General Assembly in 1781. This had repercussions in the Ohio country, especially along Lake Erie. Most of the Yankees who had settled there were anything but Loyalists, and the restoration upset them. It stiffened the independent impulse in their political culture that would eventually lead Upper Connecticut to become its own state, not part of Ohio or any of its other neighbors. In the short term the change eliminated the republican English presence to Ohio’s north, reducing tensions there.

Furthering the cause of peace were the actions of Pennsylvania and the Iroquois, whose diplomats worked tirelessly to convince English leaders on both sides of the Wars of Independence to restore friendly relations. The two states had an interest in keeping the English divided (so as not to pose a threat to either one’s independence) and peaceful (to encourage the growth of population and trade). Their entreaties were convincing enough, and the first postwar Anglo-American Congress met in Huntingdon, Connecticut, on Long Island, in the summer of 1782. The Congress and its successors solved numerous problems related to the Ohio, most importantly negotiating a border between Virginia and the Allegheny territories, in whose government the Iroquois were now taking a much more active interest. Significantly, in that agreement all parties recognized Virginia’s western territory as the land between the Ohio River and the Cherokee Nation. Carolina and England still hoped that they could reduce that land to nearly zero by helping the Cherokee push their border northward; and Virginia still expected to occupy and gain control of a good deal of land north of the Ohio River; but the treaty, passed as an act of Congress, helped clarify the limits of Ohio. From then on, south of the river would be Virginian country, while north of it would be the crazy quilt of English, French, Indian, and Mixed settlements that had taken shape over the last century.

Ohio enjoyed about twenty years of peace, a consequential time for the entire region. Ohio had never been merely a venue for imperial ambition; its independent tribes, republics and villages had existed between and outside the empires throughout the colonial era. But now, with so many more players, the local elements came to the forefront of Ohio’s political and social life. These elements had emerged when Ohio was contested by England, France, and Iroquoia. Now, the list included Canada and Louisiana (now rivals as much as partners), independent Virginia and Pennsylvania, arrivals from New Netherland and the Illinois Country and the Council of Three Fires, a vibrant and growing Moravian Church, and a motley group of immigrants from such places as Scotland and the Caribbean. People from all of these backgrounds came to the Ohio Country to find a place within the existing society, which was largely dominated by people and structures of mixed Indian and European descent. Growth was quick and steady, but not explosive. This was not the world of our own Frontier, where a man could come in with a few dollars and plant some acres of beans. But it was a world where a man could come in with some skills and some trade goods, get to know the people in town, ideally marry someone’s daughter, and get permission to farm some land belonging to the village. If he and his prospered, he might eventually be able to purchase his land outright, depending on where he was and what local laws were in effect. In this way the local communities of Ohio grew, attracting new people on their own terms.

As the settlements in the Ohio country grew, they became more complex. Ohio was still primarily a kin-based society of hunters and farmers, but many new types appeared, some from outside, others from within. They were smiths and artisans, brewers and distillers, priests and ministers, teamsters and keelboatmen, teachers and printers and lawyers. These last were becoming increasingly in demand. The region’s overlapping systems of English and French and traditional law were starting to cause problems as the towns became larger and more interconnected.

The War of the League of St. Joseph

Despite the appearance of peace and prosperity, the game of power politics continued in Ohio. The rise of a new Métis elite gave the four strongest powers - Virginia, Pennsylvania, French Canada, and the English Crown - new opportunities to try and extend their influence. All four sent agents to the main towns to give ritual gifts, create or strengthen alliances, and try to outmaneuver agents from the other powers. In general, the locals gave these agents a wary welcome. Though traditionally uneasy about imperial interference, many genuinely needed help with arranging long-distance trade deals and arbitrating disputes with neighboring communities. George Morgan, one of the most successful merchant-diplomats of the era, convened several councils of Ohio chiefs and magistrates in the Lenape town of Coshocton. He seemed to be on the way to creating in Ohio a Pennsylvanian version of the alliance that France had forged over a century earlier in the Upper Country.

By the 1790s, two states, Virginia and Canada, were drawing closer together. In part this was a reaction to Morgan’s success. It also flowed from Virginia’s ongoing disputes with England over its southern border, over the status of Bermuda, and even over a final settlement for its war of independence, which England still dragged its feet over so many years later. These matters were a source of strain within the community of English-speaking states. This was a time of ever greater cooperation among those states through the Congress, which by now was a permanent institution. But while Virginians felt that their state ought to be the natural leader of the Congress, the others frequently ignored the many unresolved issues between it and England. Feeling isolated from its ostensible allies, Virginia looked to Canada. The two states complemented each other well; Canada had unmatched experience in village politics and a network of allies, while Virginia had a large population and a strong military and militia.

Virginia and Canada first cooperated on an ad hoc basis, leading alliance councils at various points in the disputed territory. But in 1802 at Fort St. Joseph, they drafted an agreement that divided most of Ohio between them into spheres of influence. They kept their plans quiet, but word soon got out. The other English speaking states were outraged. Demands and threats followed. Virginia militiamen spread throughout the Ohio, building fortified stations to defend the settlements that were part of its new alliance. Loyalists and Pennamites arrived on the scene, and they built forts of their own. Fort Defiance was established on the River Miami-du-Lac to challenge Canadian control there, while troops from the Dominion of New England strengthened their positions on Lake Erie. It was not long before some of these forces crossed paths, and soon Ohio was aflame again.

The course of the fighting was long and convoluted and ranged north into Lakes Huron and Michigan, south into West Florida, and out to sea with the Virginian expedition to Bermuda. At times the fighting seemed about to spend itself, only to flare up again. New Netherland and Iroquoia, who had just recently begun to form ties with the Anglo-American Congress, were ambivalent; while individual bands joined with one side or the other, the states themselves stayed out of the fighting. We will skip over most of the military details for now. What is important is that Ohioans themselves were instrumental in bringing about an end to it. Where just a little earlier they had looked to the Europeans to arbitrate disputes among them, they now stepped in as arbiters in the war. Some of the pro-neutrality chiefs convened a Great Council of the Ohio in the town of Mississinewa on the upper Wabash. First meeting in 1806, it is considered the predecessor of the State of Ohio. Later Great Councils met in other towns with representatives of the warring parties in attendance, and it was at these councils that the eventual peace terms were worked out.

The southern theater of the war came to an end with the Treaty of Bath in 1808. The war in the north took a little longer to stop. By 1808 all parties had agreed to a basic plan for a neutral alliance of all the Ohio settlements, and Virginian and Pennamite forces had ceased fighting. However, English Loyalists and Canadians kept the fight going in the Lakes and the Upper Country for two more years.

From alliance to state

The War of the League of St. Joseph was the last major convulsion to rock Boreoamerica. None of the combatants achieved their goals. Canada remained the suzerain over the Upper Country, but it was treaty bound to stay out of its internal affairs and allow autonomy to non-French people living there. Virginia regained its lost territories of Bermuda and Albemarle, but it could not satisfy its ambitions in Cherokee and Ohio. After this final conflict, the major states of this part of the continent stopped trying to make war on one another and went back to the proven strategies of alliance and diplomacy.

In Ohio, a local alliance stepped into the place that empires and commanders had once had. The Great Council in the early years had to spend most of its energy on getting past wartime feuds and rivalries. After that it could turn to devising a rational legal structure for Ohio and setting up the first instututions of statewide government. It was a slow process. There was no one moment when the State of Ohio came into existence.

The continental alliance structure had a lot to do with this process. After the war, Ohioan leaders sought to restore ties with their neighbors. They accepted accepted ceremonial gifts as Onontio’s Children (the Canadian alliance) and also joined in the Iroquois Covenant Chain, symbolically extending it down the Ohio to the Mississippi. In past generations these alliances would have been mutually exclusive, but now it made sense for Ohio to be part of both. For a while the major constituents were still sending separate delagates: Ouiatenon, Coshocton, Vincennes, and so forth. By the 1830s Ohio represented itself as a unified whole. It had a permanent seat in the expanded Congress, which by now included not just the English states but also New Netherland and Iroquoia and the other new states of Poutaxia and Allegheny. The French states joined the Congress soon after, and in 1841 the alliance was made formal and permanent with the declaration of the Affiliated States of Boreoamerica with the State of Ohio as a full-fledged, coequal member.

What we call the Métis Flag has its origins in the Assiniboia settlements that in TTL became the State of Assiniboia. So its blue version furnishes the state flag. The red version is the war (militia) flag.

Flag of Ohio

Now this is a flag I made for Ohio. I played with other symbols of peace and alliance: fires, calumets, bowls. But nothing looked as good as three white bands suggesting wampum belts, the same symbolism as on the flag of Poutaxia. Green suggests neutrality among the major states (which tend to use a lot of red or blue), and it also represents fertile land and all that.

Writing the history of Ohio took a while, and there are probably still some changes to make. Ohio helped make a lot of ASB history more clear. There are a lot more Actual Dates now than there used to be for the fateful years between 1760 and 1820.

History of Ohio

Peopling the Ohio Country

As a distinct region, Ohio’s history goes back to the middle of the 17th century and the era of the fierce Iroquois attacks against seemingly everyone living west of their homeland. Sparked by competition over the fur trade and sustained by the need to avenge and recoup losses through the abduction of enemies, the wars lasted twenty years and ranged all over the Ohio country and Great Lakes. When the dust settled, Ohio was almost totally emptied, its inhabitants having relocated to refugee settlements in the Upper Country - or been carried off to Iroquoia. The Iroquois became the de facto rulers of the vacant land, using it mainly as a hunting ground. They claimed in their dealings with Europeans to be its rulers by right of conquest.

New groups began to arrive in Ohio after 1700. Empty land meant new opportunities, especially for young leaders from outside the traditional power structures of tribe and empire. Many Huron-Petun people left Huronia and established the Wyandot tribe during this era; similarly, many Iroquois left their people to found the tribe known as the Mingo. Members of existing tribes, in particular the Lenape, Miami and Shawnee, also came and established themselves during these decades, while others came from southern peoples such as the Cherokee. These disparate people gathered together in villages that lacked any clear ethnic identity, often under charismatic leaders, many of Métis background. By the 1740s a number of small republics had cropped up in the region. One lay along the White River in the center and west of the Ohio country; another dominated the Forks of the Ohio. The republics were troublesome to all the established powers of the continent. They rejected alliance with any empire and pursued an independent course.

Imperial competition was on the rise. Dutch and some English traders were coming west in greater numbers in search of furs. This challenged the power of France: the Iroquois may have considered Ohio to be their own hinterland, but the French felt the same way about it. Now they had to build up their presence to resist the challenge from their rivals. Early French settlements included Ouiatenon and Vincennes, both on the Wabash. These were somewhat awkwardly placed within the French empire. Though founded by Canada, these posts were along rivers with easy access to Louisiana. So Louisiana and Canada, the two centers of French power, soon found themselves in a rivalry of their own. Commanders of the forts, though chosen by Canada, generally also had to be acceptable to officials in Louisiana. The actual habitants around the forts eventually were largely Métis, with both French and indigenous backgrounds. Like the leaders of the republics, these habitants began the process of building a separate, independent identity in the Ohio country. Not to be ignored is the small but not insignificant population of slaves, former slaves, and free children of slaves, all of them forming a part of the community of the French settlements.

English settlers came a little later. Once the Crown gave its approval to Virginian settlement past the mountains, a trickle of people began moving west intent on agricultural settlement. They entered the complex society of Ohio with help from allied Indian groups, especially Cherokee, who accompanied them and built new villages not far from the new English centers. Settlement was managed by a few land companies, but at this point these companies engaged more in speculation than actual settlement. The English pioneers built villages that were largely self-sufficient and cut off from Virginia itself. For most of the 18th century the English population mostly stayed south of the river in what today is Upper Virginia.

So by the late 18th century, Ohio was a dynamic region of bewildering human diversity. It was a place where competing imperial ambitions contrasted with emerging local cultures wanting to govern themselves.

Wars of empire and revenge

Ohio was also a place of violence. With no clear authority and lots of rival factions, it did not take much for disputes to lead to feuds and feuds to wars. An example is the Fox War of the 1740s. It began in Detroit but spread to consume the Ohio and Illinois countries. Fought between the Fox tribe and the French alliance of the Upper Country, it had no real economic cause, but arose from ethnic conflict and perceived slights. The cycle of revenge lasted for years until it was finally spent, and the Fox were driven west of Lake Michigan.

Imperial wars also made themselves felt in Ohio. The eighteenth century in this timeline was not quite as polarized as our own: England and France were rivals, certainly, but their wars were not quite so numerous, and their colonists had less of a sense of being locked in an eternal fight to the death. And anyway, as in our timeline, imperial wars influenced politics and fighting in Ohio, but they did not drive it directly. England and France could fight in Europe while life in Ohio continued almost like normal, and by the same token fighting in Ohio could break out between the colonists or their allies even as the kings in Europe were trying to get along. And all the while, republics, neutral tribes, and traders did their best to avoid the imperial conflicts, or use them to their advantage.

The Wars of Independence in the English colonies shook Ohio far more. When the Anglo-American world shattered, new rivalries appeared that made themselves felt in the west. Several of the colonies had had claims in Ohio that they had not tried hard to enforce before, but now that land seemed much more important. In 1772 Virginia sent an expedition of militia down the river, building blockhouses and crude forts all along the way. This had the effect of angering the French in their small forts; so while the French in Canada eagerly supported revolutionaries in the north, Virginia got little sympathy from the French in Louisiana. But the blockhouses became the seeds of a new generation of settlements; by 1800 Virginia thoroughly dominated the land south of the river. Revolutionary Connecticut, too, sent an expedition to seize Fort Sanduskey, the most important English post on Lake Erie. Though they seized the fort, the English troops crossed the bay and dug in to new positions.

Alliances extended the fighting to a wider area. The Iroquois themselves stayed out of the Wars of Independence, trying to stay on friendly terms with both sides. They signed an accord with Virginia ceding to them their claim to much of Upper Virginia, and they kept up trade with Crown posts. But other groups did take sides. The Connecticuter force that attacked Sanduskey was in fact more than half Indian or Mixed, recruited from settlements on the Cuyahoga. The defenders included a large force of Miamis. A delegation of Virginians and allies to the White River republic turned violent when the leaders there refused to give their support to the newly independent state; the militia attacked the village and ultimately were forced to retreat back to their base on the Ohio River. At Ouiatenon, fighting between pro-republican and pro-loyalist Indians grew heated. Following orders from Quebec, the commander let the republican sympathizers into the fort and closed the gate, but he did not let them onto the ramparts to attack their foes. They left after a few days; Ouiatenon itself was spared of further violence, but skirmishes continued in the countryside.

The peace after independence

The Wars of Independence drifted to a halt rather than build to a climax. In the south they degenerated into skirmishes and petty violence along the Virginian-Carolian border, while in the north the English shored up their support in southern New England and relied on diplomacy and politics to lure other states back into the fold. The real coup was in Connecticut, which elected a loyalist majority to its General Assembly in 1781. This had repercussions in the Ohio country, especially along Lake Erie. Most of the Yankees who had settled there were anything but Loyalists, and the restoration upset them. It stiffened the independent impulse in their political culture that would eventually lead Upper Connecticut to become its own state, not part of Ohio or any of its other neighbors. In the short term the change eliminated the republican English presence to Ohio’s north, reducing tensions there.

Furthering the cause of peace were the actions of Pennsylvania and the Iroquois, whose diplomats worked tirelessly to convince English leaders on both sides of the Wars of Independence to restore friendly relations. The two states had an interest in keeping the English divided (so as not to pose a threat to either one’s independence) and peaceful (to encourage the growth of population and trade). Their entreaties were convincing enough, and the first postwar Anglo-American Congress met in Huntingdon, Connecticut, on Long Island, in the summer of 1782. The Congress and its successors solved numerous problems related to the Ohio, most importantly negotiating a border between Virginia and the Allegheny territories, in whose government the Iroquois were now taking a much more active interest. Significantly, in that agreement all parties recognized Virginia’s western territory as the land between the Ohio River and the Cherokee Nation. Carolina and England still hoped that they could reduce that land to nearly zero by helping the Cherokee push their border northward; and Virginia still expected to occupy and gain control of a good deal of land north of the Ohio River; but the treaty, passed as an act of Congress, helped clarify the limits of Ohio. From then on, south of the river would be Virginian country, while north of it would be the crazy quilt of English, French, Indian, and Mixed settlements that had taken shape over the last century.

Ohio enjoyed about twenty years of peace, a consequential time for the entire region. Ohio had never been merely a venue for imperial ambition; its independent tribes, republics and villages had existed between and outside the empires throughout the colonial era. But now, with so many more players, the local elements came to the forefront of Ohio’s political and social life. These elements had emerged when Ohio was contested by England, France, and Iroquoia. Now, the list included Canada and Louisiana (now rivals as much as partners), independent Virginia and Pennsylvania, arrivals from New Netherland and the Illinois Country and the Council of Three Fires, a vibrant and growing Moravian Church, and a motley group of immigrants from such places as Scotland and the Caribbean. People from all of these backgrounds came to the Ohio Country to find a place within the existing society, which was largely dominated by people and structures of mixed Indian and European descent. Growth was quick and steady, but not explosive. This was not the world of our own Frontier, where a man could come in with a few dollars and plant some acres of beans. But it was a world where a man could come in with some skills and some trade goods, get to know the people in town, ideally marry someone’s daughter, and get permission to farm some land belonging to the village. If he and his prospered, he might eventually be able to purchase his land outright, depending on where he was and what local laws were in effect. In this way the local communities of Ohio grew, attracting new people on their own terms.

As the settlements in the Ohio country grew, they became more complex. Ohio was still primarily a kin-based society of hunters and farmers, but many new types appeared, some from outside, others from within. They were smiths and artisans, brewers and distillers, priests and ministers, teamsters and keelboatmen, teachers and printers and lawyers. These last were becoming increasingly in demand. The region’s overlapping systems of English and French and traditional law were starting to cause problems as the towns became larger and more interconnected.

The War of the League of St. Joseph

Despite the appearance of peace and prosperity, the game of power politics continued in Ohio. The rise of a new Métis elite gave the four strongest powers - Virginia, Pennsylvania, French Canada, and the English Crown - new opportunities to try and extend their influence. All four sent agents to the main towns to give ritual gifts, create or strengthen alliances, and try to outmaneuver agents from the other powers. In general, the locals gave these agents a wary welcome. Though traditionally uneasy about imperial interference, many genuinely needed help with arranging long-distance trade deals and arbitrating disputes with neighboring communities. George Morgan, one of the most successful merchant-diplomats of the era, convened several councils of Ohio chiefs and magistrates in the Lenape town of Coshocton. He seemed to be on the way to creating in Ohio a Pennsylvanian version of the alliance that France had forged over a century earlier in the Upper Country.

By the 1790s, two states, Virginia and Canada, were drawing closer together. In part this was a reaction to Morgan’s success. It also flowed from Virginia’s ongoing disputes with England over its southern border, over the status of Bermuda, and even over a final settlement for its war of independence, which England still dragged its feet over so many years later. These matters were a source of strain within the community of English-speaking states. This was a time of ever greater cooperation among those states through the Congress, which by now was a permanent institution. But while Virginians felt that their state ought to be the natural leader of the Congress, the others frequently ignored the many unresolved issues between it and England. Feeling isolated from its ostensible allies, Virginia looked to Canada. The two states complemented each other well; Canada had unmatched experience in village politics and a network of allies, while Virginia had a large population and a strong military and militia.

Virginia and Canada first cooperated on an ad hoc basis, leading alliance councils at various points in the disputed territory. But in 1802 at Fort St. Joseph, they drafted an agreement that divided most of Ohio between them into spheres of influence. They kept their plans quiet, but word soon got out. The other English speaking states were outraged. Demands and threats followed. Virginia militiamen spread throughout the Ohio, building fortified stations to defend the settlements that were part of its new alliance. Loyalists and Pennamites arrived on the scene, and they built forts of their own. Fort Defiance was established on the River Miami-du-Lac to challenge Canadian control there, while troops from the Dominion of New England strengthened their positions on Lake Erie. It was not long before some of these forces crossed paths, and soon Ohio was aflame again.

The course of the fighting was long and convoluted and ranged north into Lakes Huron and Michigan, south into West Florida, and out to sea with the Virginian expedition to Bermuda. At times the fighting seemed about to spend itself, only to flare up again. New Netherland and Iroquoia, who had just recently begun to form ties with the Anglo-American Congress, were ambivalent; while individual bands joined with one side or the other, the states themselves stayed out of the fighting. We will skip over most of the military details for now. What is important is that Ohioans themselves were instrumental in bringing about an end to it. Where just a little earlier they had looked to the Europeans to arbitrate disputes among them, they now stepped in as arbiters in the war. Some of the pro-neutrality chiefs convened a Great Council of the Ohio in the town of Mississinewa on the upper Wabash. First meeting in 1806, it is considered the predecessor of the State of Ohio. Later Great Councils met in other towns with representatives of the warring parties in attendance, and it was at these councils that the eventual peace terms were worked out.