You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

A House Divided Against Itself: An 1860 Election Timeline

- Thread starter TheRockofChickamauga

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 67 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

XLVIII: March on Managua XLIX: The Road to Groveton XLX: The Groveton Races Groveton Order of Battles Maps for the Battle of Groveton XLXI: Once More Unto The Breach, Dear Friends, Once More Map for the Battle of Warrenton XLXII: Their Souls Are Rolling On!The upcoming election results are certainly going to have a profound impact on the development of all of those endeavors.With an earlier transcontinental railroad, I wonder if this will see a faster expansion across the Great Plains, though with a deeply divided congress, I doubt a homestead bill will be passed as it won't have enough support.

XLI: Election Night, 1864

XLI: Election Night, 1864

As reports of the completion of the Southern Sea Line were being received on the telegram line, the populace that had previously been so enamored with all reports of its progress gave it only a moment's notice. For it had arrived on the day of the presidential election, and as seemed to be a recurring trend over the last decade, its results were seen as holding the fate of the nation in their balance. Republicans had carried the gubernatorial elections in both the early voting states of Indiana and Maine, with Republican and Morton ally, Pleasant A. Hackleman, comfortably defeating Matthew L. Brett and James Wilson, candidates of the Democrats and Unionists respectively, and generally seen as surrogates for the presidential nominees. These bellwether victories were good signs for the Republicans in the election to come, giving the former miller from Centerville quite the reason for confidence heading into November 7.

As was expected, the results were first in from South Carolina, as their state legislature ultimately cast the votes for electors. With little surprise, they rallied around their native son Orr and gave him the first electoral votes with their eight. Orr's candidacy had failed to ignite the same blaze across the South as Toombs' run four years prior, but at least among the powerful in that region support for his cause was widespread. Almost as unsurprisingly, Vermont's 5 electoral votes were cast for Morton, carrying the state by a crushing 87.8%, which was to be his strongest performance of the night. The smaller states of 4 vote Arkansas and 8 vote Iowa reported their results soon thereafter, going for Orr and Morton respectively. Arkansas was safely on the side of the Southern Democrats, but Iowa had been a close run affair, with Morton defeating Lincoln there by under 4,000 votes. Already the ripples of Harpers Ferry were beginning to make their appearance, and the signs bode ill for the Unionists.

Rhode Island went to Morton by the expectedly decisive margin, with Minnesota and Wisconsin not far behind to give him 16 electoral votes between them. Delaware, a state many expected to have already announced its results, remained in a close heat. All four candidates had performed respectably within the state, but a narrow margin of several hundreds was expected to separate the two front-runners: Bright and Lincoln. Both candidates needed every state possible within their column to ensure them a place over the other in a hypothetical contingent election, the possibility of which already was looking unlikely, meaning their already slender path ran through the closely divided state. Ultimately, 664 votes placed Bright ahead of Lincoln and thus gave him 3 electoral votes. While partisans of the Unionists and Democrats closely monitored that contest, the nation at large was fixed on whether Morton and the Republicans would reach 158 majority necessary for victory.

The same telegram line that had proclaimed the completion of the Southern Sea Line came alive with much reception once more that day, as it carried the results of California and Oregon to anxious citizens in the East. 5 vote California, noted for the deep and bitter divisions among its opposition groups to Republicans, had gone for Morton by an ample difference, but Oregon, always somewhat of a political maverick, had given substantial performances from all four nominees with Lincoln ultimately emerging as the winner of its 3 electoral votes. Kansas, still scarred by the memories of its bloody origins, would go decisively for Morton, representative of the total control the Jayhawkers now held in the region and its three electoral votes. As it stood, Morton was leading with 37 and was well on his way to an immediate electoral majority, while Orr trailed with 12, and Lincoln and Bright both held 3.

Soon, the regions in little doubt began to return results only boosting the two-leading candidates. Orr would sweep the deep Southern states of Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, and Florida for an additional 39 electoral votes. Morton, meanwhile, would consolidate the New England states with victories in Maine, New Hampshire, and Massachusetts totaling 24 electoral votes, in addition to winning the final upper Midwestern state, Michigan, for another 8. It was here, however, that the problems facing the opposition to Morton became evident. Orr, his strongest opponent thus far, had very little room left to expand electorally, with an additional 2 or 3 states within his reach at best. Outright victory for either Lincoln or Bright at this point became a statistical impossibility, condemning them to hope for an improbable contingent election. As long as there were no surprises, Morton seemed destined to be president-elect come November 8, and this notion already had the leaders of the South in whispered discussion about the future.

Only seasoned politicos, however, noted this occurrence, and the general public still remained avidly focused on the incoming results. A pair of border states came next, with Missouri's 11 electoral votes going for Bright and Maryland's 7 for Lincoln. Tennessee's 12 electoral votes going for Lincoln were reported next, and of the three candidates on the ballot, Orr had placed a surprising third, with over 30,000 votes separating him from Lincoln. For the Unionists, however, had little time for triumph, as Lincoln's home state Illinois, in addition to Indiana, were called for Morton soon thereafter. Morton now stood at 94 electoral votes, with the massive prizes of Ohio, Pennsylvania, and New York looming ahead. After perennial swing state New Jersey's 7 electoral votes went for Morton, it seemed certain that these three juggernauts, which common consensus dictated were more Republican leaning, were his as well and thus it seemed the night was over. Bright had gone to sleep following his defeat in Indiana, while Lincoln began reading volumes from the library of the telegraph office following New Jersey's announcement.

Their cynicism would prove to be well-founded, as the rest of night showed that they had nothing more to gain electorally. Virginia and North Carolina went for Orr, while Ohio, Pennsylvania, and New York lined up in the Republican column as expected. Thus, when final electoral results were tallied, Morton had won with 191 electoral votes, followed by Orr's 76, Lincoln's 33, and Bright's 14. The popular vote, however, had been an entirely different story. Morton had also won there with 37.4% of the 4,877,998 total votes cast, but Lincoln and the Unionists nabbed second place with 27.1%, followed by Bright and the Democrats earning 22.8%, and the Southern Democrats earning a measly 12.7%.

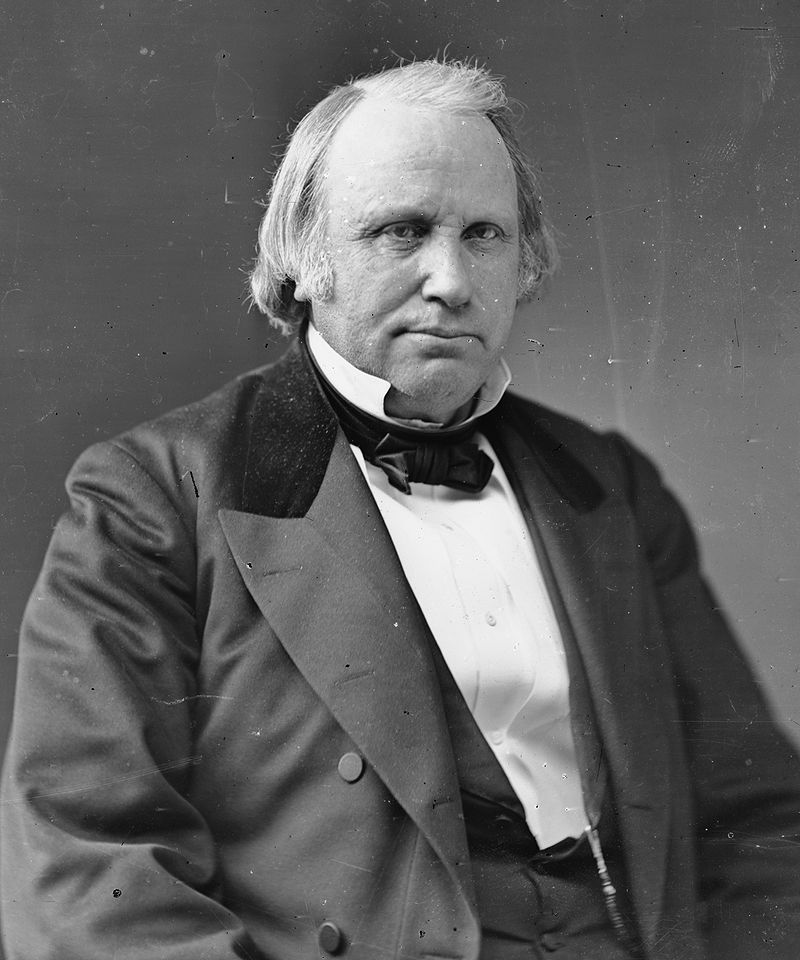

Finally, after a decade and a half with moderates and compromisers at the helm, one side in the great national struggle had prevailed over the other, as Oliver P. Morton and Henry Wilson were scheduled for their inaugurations on March 4. Predictably, the slave states took this defeat with little grace, and tensions already simmering below the surface were soon to be boiling to the top. As their leaders had predicted, the nation would eventually give them a justification for secession in their eyes, and following Morton's victory that time had come. Forgetting Yancey, forgetting Clay, forgetting Washington, the burdens and abuses of a continuing union with those states had become too much to bear. The long-waiting seeds of disunion were finally properly ready to germinate forth in their most dramatic of fashions.

President-elect Oliver P. Morton and Vice President-elect Henry Wilson

I wonder if any states will secede given how little grace the slave states handled this election.

I don't actually expect the state's to declare secession from the Union. After the disaster that was Yancy's rebellion, I think most (if not all) will grumble and proclaim "an abolitionist plot is afoot," but resort to political gridlock in Congress instead of leaving the Union. However, I think this is just the beginning for political violence in the southern states as pro secession/anti Morton guerrilla groups will form and attack open unionists and suspected abolitionists in hopes of forcing the states to leave the Union. Kinda like Bushwackers, but with less state support.

I think that’s plausible among many states that seceded but I can see those that had near-universal support for secession IOTL to at least try.I don't actually expect the state's to declare secession from the Union. After the disaster that was Yancy's rebellion, I think most (if not all) will grumble and proclaim "an abolitionist plot is afoot," but resort to political gridlock in Congress instead of leaving the Union. However, I think this is just the beginning for political violence in the southern states as pro secession/anti Morton guerrilla groups will form and attack open unionists and suspected abolitionists in hopes of forcing the states to leave the Union. Kinda like Bushwackers, but with less state support.

The problem (if it's a problem) isn't the electoral college; remember, Morton won a plurality in the popular vote. Lincoln did too in OTL 1860. In both cases, what got them into office was the plurality voting system. For OTL Douglas or TTL Lincoln to win, you'd need something like approval voting or ranked voting where voters can indicate their second choice as well as their first.Shows the unfair nature of the Electoral College. Surely Lincoln would have beaten.Morton in a runoff -as Douglas would have done to.Lincoln in.OTL?

Lincoln certainly supports the continuance of the Union, and I'm planning of addressing the relations between Lincoln and Morton during the transition period, even if I haven't definitively staked out where (chapter-wise) that will take place.Very well written! So after the war starts, will Lincoln go visit Morton and offer his total support, as Douglas did for Lincoln in OTL?

They have their justification, now the nation will see if they get their secession.I wonder if any states will secede given how little grace the slave states handled this election.

These are some really interesting ideas. I'm going to have look into incorporating Deep South bushwhackers, as that seems like something that really could occur. Does anyone have any name suggestions? The Tillers? The Latifundia? Something else?I don't actually expect the state's to declare secession from the Union. After the disaster that was Yancy's rebellion, I think most (if not all) will grumble and proclaim "an abolitionist plot is afoot," but resort to political gridlock in Congress instead of leaving the Union. However, I think this is just the beginning for political violence in the southern states as pro secession/anti Morton guerrilla groups will form and attack open unionists and suspected abolitionists in hopes of forcing the states to leave the Union. Kinda like Bushwackers, but with less state support.

I suppose it would depend on if the South would be willing to participate in an election where their preferred candidate had been booted off the ballot. If nothing else, it would certainly provide them with plenty of talking points of how their views are being considered.Shows the unfair nature of the Electoral College. Surely Lincoln would have beaten.Morton in a runoff -as Douglas would have done to.Lincoln in.OTL?

I'll say this: there are going to be secession conventions, but for now I hold back from revealing the ultimate result.I think that’s plausible among many states that seceded but I can see those that had near-universal support for secession IOTL to at least try.

Or possibly for either man to have not taken some of the stands they did IOTL and ITTL respectively, but I digress.The problem (if it's a problem) isn't the electoral college; remember, Morton won a plurality in the popular vote. Lincoln did too in OTL 1860. In both cases, what got them into office was the plurality voting system. For OTL Douglas or TTL Lincoln to win, you'd need something like approval voting or ranked voting where voters can indicate their second choice as well as their first.

1864 Election Results

| State | Morton (R-IN) | Bright (D-IN) | Orr (SD-SC) | Lincoln (U-IL) |

| Alabama | XXXXXXX | 38,954 | 52,390 | 3,284 |

| Arkansas | XXXXXXX | 18,756 | 34,567 | 1,879 |

| California | 59,070 | 21,486 | 10,365 | 34,897 |

| Connecticut | 38,103 | 14,323 | 6,276 | 23,657 |

| Delaware | 3,768 | 5,934 | 1,465 | 5,270 |

| Florida | XXXXXXX | 2,495 | 10,585 | 487 |

| Georgia | XXXXXXX | 12,854 | 55,676 | 39,254 |

| Illinois | 153,140 | 45,923 | 1,465 | 149,327 |

| Indiana | 101,794 | 97,465 | 1,198 | 85,293 |

| Iowa | 50,451 | 34,293 | 923 | 46,934 |

| Kansas | 15,197 | 1,587 | 600 | 6,354 |

| Kentucky | 12,940 | 35,950 | 23,940 | 77,679 |

| Louisiana | XXXXXXX | 5,142 | 32,454 | 14,934 |

| Maine | 60,405 | 9,246 | 354 | 35,958 |

| Maryland | 3,295 | 19,384 | 27,394 | 46,129 |

| Massachusetts | 117,852 | 32,045 | 2,576 | 25,896 |

| Michigan | 73,012 | 32,945 | 1,094 | 49,043 |

| Minnesota | 17,011 | 7,984 | 284 | 10,293 |

| Mississippi | XXXXXXX | 14,283 | 53,646 | 3,929 |

| Missouri | 21,930 | 69,732 | 14,587 | 67,592 |

| New Hampshire | 39,139 | 9,203 | 322 | 17,938 |

| New Jersey | 62,187 | 34,203 | 3,256 | 29,101 |

| New York | 345,387 | 199,202 | 29,431 | 121,390 |

| North Carolina | XXXXXXX | 38,302 | 50,018 | 11,293 |

| Ohio | 231,827 | 75,842 | 9,999 | 119,340 |

| Oregon | 4,321 | 2,854 | 2,304 | 5,429 |

| Pennsylvania | 249,327 | 79,212 | 19,405 | 147,555 |

| Rhode Island | 11,854 | 1,405 | 389 | 6,303 |

| Tennessee | XXXXXXX | 45,902 | 36,392 | 68,195 |

| Texas | XXXXXXX | 1,824 | 36,392 | 2,910 |

| Vermont | 59,088 | 1,453 | 777 | 5,943 |

| Virginia | 2,000 | 51,976 | 76,894 | 44,365 |

| Wisconsin | 89,504 | 49,096 | 596 | 14,508 |

| TOTALS | 1,822,602 | 1,111,255 | 621,782 | 1,322,359 |

| PERCENTAGE | 37.4% | 22.8% | 12.7% | 27.1% |

| EC VOTES | 191 | 14 | 76 | 33 |

Redeemers? Constitutionalists? ("Defend our nation from the radicalism of the Black Republican who seeks to overthrow our republic!")The Tillers? The Latifundia? Something else?

Deeply ironic that Lincoln did fairly well in the southern states.***: South Carolina voted for its electors via its state assembly

State Morton (R-IN) Bright (D-IN) Orr (SD-SC) Lincoln (U-IL) Alabama XXXXXXX 38,954 52,390 3,284 Arkansas XXXXXXX 18,756 34,567 1,879 California 59,070 21,486 10,365 34,897 Connecticut 38,103 14,323 6,276 23,657 Delaware 3,768 5,934 1,465 5,270 Florida XXXXXXX 2,495 10,585 487 Georgia XXXXXXX 12,854 55,676 39,254 Illinois 153,140 45,923 1,465 149,327 Indiana 101,794 97,465 1,198 85,293 Iowa 50,451 34,293 923 46,934 Kansas 15,197 1,587 600 6,354 Kentucky 12,940 35,950 23,940 77,679 Louisiana XXXXXXX 5,142 32,454 14,934 Maine 60,405 9,246 354 35,958 Maryland 3,295 19,384 27,394 46,129 Massachusetts 117,852 32,045 2,576 25,896 Michigan 73,012 32,945 1,094 49,043 Minnesota 17,011 7,984 284 10,293 Mississippi XXXXXXX 14,283 53,646 3,929 Missouri 21,930 69,732 14,587 67,592 New Hampshire 39,139 9,203 322 17,938 New Jersey 62,187 34,203 3,256 29,101 New York 345,387 199,202 29,431 121,390 North Carolina XXXXXXX 38,302 50,018 11,293 Ohio 231,827 75,842 9,999 119,340 Oregon 4,321 2,854 2,304 5,429 Pennsylvania 249,327 79,212 19,405 147,555 Rhode Island 11,854 1,405 389 6,303 Tennessee XXXXXXX 45,902 36,392 68,195 Texas XXXXXXX 1,824 36,392 2,910 Vermont 59,088 1,453 777 5,943 Virginia 2,000 51,976 76,894 44,365 Wisconsin 89,504 49,096 596 14,508 TOTALS 1,822,602 1,111,255 621,782 1,322,359 PERCENTAGE 37.4% 22.8% 12.7% 27.1% EC VOTES 191 14 76 33

Redeemers? Constitutionalists? ("Defend our nation from the radicalism of the Black Republican who seeks to overthrow our republic!")

Deeply ironic that Lincoln did fairly well in the southern states.

Redeemers might be it, as that was their name for a movement with similar goals IOTL.Redeemers? Constitutionalists? ("Defend our nation from the radicalism of the Black Republican who seeks to overthrow our republic!")

Deeply ironic that Lincoln did fairly well in the southern states.

As for Lincoln, I must admit that I'm happy with how his character turned out (now that he will be shuffling out of prominence soon). Not only was Alexander Stephens was running-mate, but he performed well in the South. Quite the divergence from OTL.

Ironic indeed!

XLII: Watch, Wait, and Wither

XLII: Watch, Wait, and Wither

Three weeks after the election of Morton, the convention was announced. Claiming that they had been pushed into action by the looming threats of radical abolition under the upcoming Morton administration, a gathering of 181 delegates at South Carolina Institute Hall in Charleston on November 28 to debate and decide on the question of secession was called for by the vocal Fire-Eater governor Milledge Bonham and eagerly approved by the state legislature. Many of the states' leading figures, ranging from Robert Rhett to Francis Pickens to Christopher Memminger to Wade Hampton III to Laurence M. Keitt, were set to arrive. In a worrying sign of what was to come, both of South Carolina's sitting senators, James Chestnut Jr. and James Hammond, would resign from their seats in the United States Senate to take up seats in the upcoming convention. The nation went into an unparalleled uproar.

Immediately, Lincoln would dispatch telegraphs to Governor Bonham and James L. Orr inquiring what was the meaning and intent of the convention. Bonham, who had already began referring to his state as an independent nation in his private correspondence with fellow South Carolinians, sent no reply to the president. Orr, who was notable for his absence from the upcoming event, would send a terse response claiming to have neither knowledge of nor involvement with the upcoming gathering. He would also, however, not disavow them. With rumors flying of other legislatures within the Deep South preparing similar conventions, and even one that surviving members of Yancey's Rebellion had been sighted landing at Charleston to influence the upcoming events, Lincoln would convene an urgent cabinet meeting to decide on what course of action his administration should take in addressing the issue.

From the outset, Lincoln made clear that his first and utmost priority was upholding the sanctity of the Union, and he requested that his cabinet officials take a similar oath in front of each other to hold to that same goal. This they would do, and with that the meeting would commence. As always seemed to occur in his conferences, the voices of Secretary of War Wright and Postmaster General Stephens rose to the fore. Following Lincoln's announcement that the South Carolina convention had indeed convened and begun deliberations, Wright immediately called for action. He believed the only safe course of action was to crush the fomenting plot in the cradle before it developed into a full-blown insurrection. His view was only reinforced when Lincoln's private secretary, John Nicolay, burst into the meeting carrying a telegram confirming that Francis W. Pickens, a former governor of South Carolina and noted supporter of secession, had been selected to head the convention. With this in hand, as well as Bonham's non-response, Wright asked Lincoln for permission to immediately begin preparations for dissolving the convention and other appropriate measure to quash any attempt at secession.

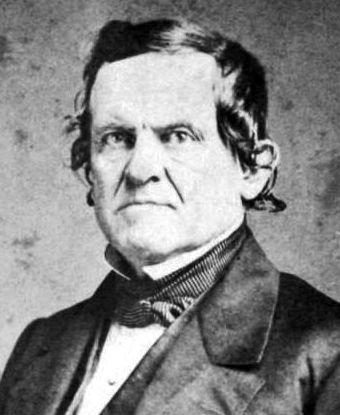

Francis W. Pickens, president of the South Carolina Secession Convention

Seeing that no consensus was likely to come about, Lincoln decided to place three options before his cabinet and put them to a vote. By that, he hoped, he could see where they stood in nothing else. The first he proposed was in line with Wright and Ewing, calling for immediate action, perhaps even of a military nature if necessary, to forcibly dissolve the convention. The second followed Stephens' counsel by allowing for tempers to cool and for the matter to blow over by acting in the least provocative manner possible. Third, he proposed a watch and wait course of action, neither committing nor condemning any course of action at the moment and instead allowing for events to unfurl. The results were perhaps unsurprising considering the course the nation had previously charted over the last decade and a half. Wright and Ewing supported the first proposition, while Stephens voted for the second. Bates, Everett, Stanly, and Johnson would all endorse the third. Already leaning towards that direction, Lincoln announce that they would chart the course of the third option.

Already having a bad taste in his mouth from being overturned or ignored in past presidential decisions in the administration, and now having that occur again when his advice had been most important in his opinion, Wright believed he was ultimately left with only one option for his future. After Lincoln adjourned the meeting, Wright would return to his Washington boardinghouse apartment and draft a letter of resignation. Claiming that he could not, in good conscience, continue to labor with an administration that had continually disregarded or failed to support his decisions at the most critical junctures, he decided to step down and allow Lincoln to appoint a man more aligned with his vision in his place. Receiving the missive the next day, Lincoln would call Wright in for one final meeting. Unable to persuade him to stay on with the administration, Lincoln wished him well and thanked him for dutiful and capable service throughout his tenure.

It was to be their last meeting, as Wright, who was already in declining health, continue to deteriorate. Despite some hopes of recovery in retirement, he was not aided by his return to his home in Indiana and would ultimately die on July 27, 1865. His continual warnings about the magnitude of underlying secession would prove to be prophetic, although at the moment his departure most primarily concerned Lincoln with finding a replacement for him in the War Department during such uncertain times. Hoping not to rock the boat, Lincoln allowed the Assistant Secretary of War, George Briggs (who had managed to secure election in 1864 as one of two Unionists sent to the U.S. House of Representatives from New York), to assume the full position on an acting basis, thereby avoiding both a battle in the Senate and Briggs having to surrender his upcoming House seat. Privately, Stephens was jubilant at Wright's departure, claiming that little else could have been more advantageous to the administration in its careful negotiations with the South than the departure of the despised Secretary of War, although he acknowledged that Morton's upcoming administration still would complicate those efforts.

Acting Secretary of War George Briggs

If Wright's departure could be seen as a olive branch to the South, it would prove to be little more than a trampled one soon swept aside. The South Carolina Secession Convention continued in their efforts behind closed doors, but even then it soon became abundantly clear that little other than secession was being contemplated. By the third day, November 30, a committee of seven headed by Rhett had been convened to draft an ordinance of secession to be considered by the body as a whole. One week later, and on December 7, the committee returned their report. By this point, only one man had risen to become a vocal opponent of secession: James L. Petigru. Born shortly after the inauguration of President Washington in 1789, Petigru had also served as a voice of moderation and reason within his otherwise volatile home state throughout his time in politics. He had served as a key conduit between Washington and Charleston during the Nullification Crisis three decades earlier, and seemed poised to play a similar role again at the convention. His patriarchal status, rather than his politics, had given him a seat there, although he hoped to use that position to the best of his means to once more hold back the state.

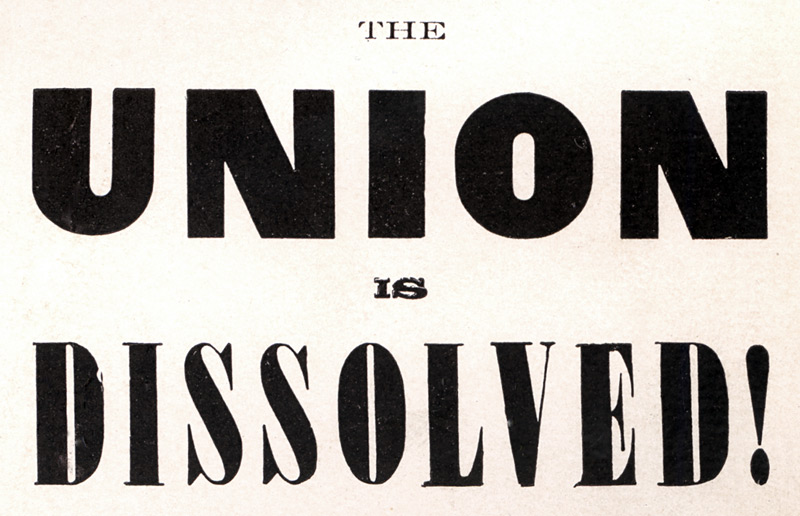

During the debates over the document, he continued to rise to stir up what little opposition he could against it, although he himself realized that he was gaining little traction. The vote to approve or reject the ordinance was scheduled for December 11. The date arrived and the convention assembled, although he was notably absent. Petigru had died quietly in his sleep the night before, still holding firm to his convictions of Union. Irregardless of this, the vote was still held. When the results were tallied, it came back with unanimous support in favor. South Carolina was withdrawn from the Union, and the inferno was ignited.

Excerpt from a bulletin of the Charleston Mercury

I'm guessing that Tennessee and North Carolina at the very least don't secede.Four year delay and a previous failed revolt. How many fewer states will secede this time I wonder?

At the very least, some sort of Nickajack/East Tennessee might be more viable ITTL.I'm guessing that Tennessee and North Carolina at the very least don't secede.

Threadmarks

View all 67 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

XLVIII: March on Managua XLIX: The Road to Groveton XLX: The Groveton Races Groveton Order of Battles Maps for the Battle of Groveton XLXI: Once More Unto The Breach, Dear Friends, Once More Map for the Battle of Warrenton XLXII: Their Souls Are Rolling On!

Share: