Just wanted to say how much I love this timeline so far. It's a blast to read and feels really well researched. I honestly view this in the same realm as TheKnightIrish's Glorius Union TL. Very well done sir, and I look forward to the next update!

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Wrapped in Flames: The Great American War and Beyond

- Thread starter EnglishCanuck

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 158 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 126: The Balance of Power in North America Chapter 127: What If? Chapter 128: 1866 A Year in Review Chapter 129: Grasping at Thrones Chapter 130: Plots in Motion Chapter 131: Trans-Atlantic Troubles Chapter 132: A Want of Preparation Chapter 133: Alarms IgnoredJust wanted to say how much I love this timeline so far. It's a blast to read and feels really well researched. I honestly view this in the same realm as TheKnightIrish's Glorius Union TL. Very well done sir, and I look forward to the next update!

Many thanks! I wouldn't personally liken this piece to A Glorious Union TL. TheKnightIrish's work is leagues above mine IMO, but thank you for the kind words!

I'm hoping to have Chapter 41 up by the weekend! Then Chapter 42 will round out 1862, with Chapter 43 definitively ending the year and Chapter 44 Général Janvier bringing in 1863.

How far do you plan to take this TL? Just to the war's end or far after?

Well so far it's a toss up. I have up to the 1880s firmly plotted out, but with the writing I've been doing part of me really wants to take a crack at a purely narrative version of this idea since I've been getting progressively more and more into the heads of some of these historical figures (Seward, Macdonald, Wolseley, Hancock, Denison, Longstreet, ect) so it feels like something that would be fun to write. I could honestly write the war as a trilogy and have had some ideas for stories set in a post-war world where global relations are radically different due to the events of this war. Though I do have the rough notes for a purely Canadian alternate history short worked out.

However, currently I intend to finish the war here and go at least to the aftermath of the election of 1872.

That being said...

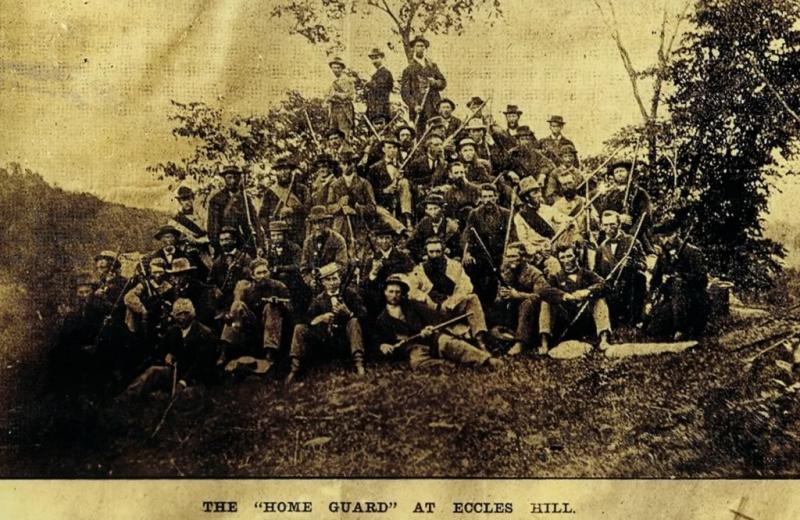

Home Guard units responding to the Crisis of 1867. The haphazard mobilization of Volunteers and militia would force the Canadian government to reconsider their defence policy

Though Volney Ashford originally raised his saber for Queen Victoria, he is seen here in the uniform of the Honolulu Dragoons shortly after swearing his saber to Queen Emma just before the Regency Emergency

Empress-Regent Eugenie, some would blame her meddling for the events of 1873

Major General Phillip Kearny accepts his orders to command the joint action which will finally end Lone Wolf's War

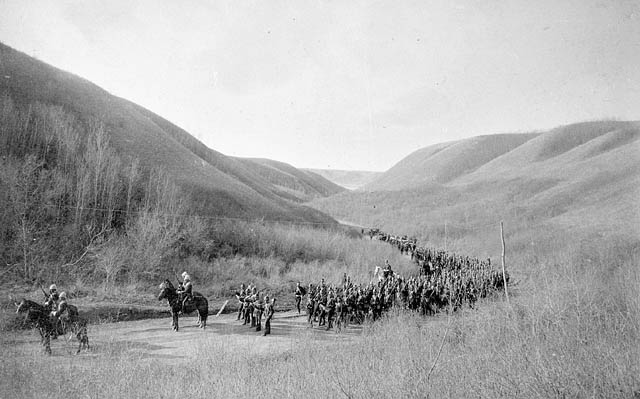

Canadian troops in column during the Great Plains War

Rear Admiral James E. Jouett aboard his flagship the ironclad USS Trenton with squadron staff during the Samoan Crisis. The outcome would finally settle American Pacific ambitions though putting them at loggerheads with the powers of the putative Imperial Entente

I'm guessing it has something to do with Louis Riel and the Métis but I could be wrong.THE GREAT PLAINS WAR?!

(caps intentional)

A lot of these pictures involve the US in some way. Makes me feel like there is no CS :/

THE GREAT PLAINS WAR?!

(caps intentional)

I'm guessing it has something to do with Louis Riel and the Métis but I could be wrong.

Well I can say for certain it has something to do with the Great Plains! Let's just say the 1870s-1880s are interesting in TTL.

A lot of these pictures involve the US in some way. Makes me feel like there is no CS :/

I plead the fifth.

Though late, I can assure you Chapter 41 will be up tomorrow, with Chapter 42 following next week! Then we finally wrap up 1862.

Chapter 41: Across the Continent Pt. 1 When the Saints Go Marching In

Chapter 41: Across the Continent Pt. 1 When the Saints Go Marching In

“Yea, in the strength of the Lord did we go forth to battle against the Lamanites; for I and my people did cry mightily to the Lord that he would deliver us out of the hands of our enemies, for we were awakened to a remembrance of the deliverance of our fathers.” – Mosiah 9:17

“The whisperings of the Spirit to us have invariably been of the same import, to depart, to go hence, to flee into the mountains, to retire to our strongholds that we may be secure in the visitations of the Judgments that must pass upon this land, that is crimsoned with the blood of Martyrs; and that we may be hid, as it were, in the clefts of the rocks, and in the hollows of the land of the Great Jehovah, while the guilty land of our fathers is purifying by the overwhelming scourge.” – Brigham Young to the Saints at Mount Pisgah and Garden Grove, Iowa Territory, January 27, 1847

“After the surprising Confederate victory in February, Sibley had proceeded north with his 2,200 remaining men. Skirmishing at Glorietta Pass had failed to slow him, and he had marched north to lay ‘siege’ to the Federal forces at Fort Union. Though he did not outnumber these forces, and could not realistically cut them off, a series of sharp skirmishes and raids would define the action from March to July before the August heat settle both sides into a sense of complacency.

Washington was alarmed by this sudden Confederate advance on the periphery. Canby, who was exchanged in late June, was called to Washington to answer for the defeats suffered there. Meanwhile, Lincoln had little choice but to assign an older officer to the command on the frontier.

Brigadier General William Selby Harney was appointed commander of the South West region, and given authority for all Union forces from Nevada to Colorado.

The choice of Harney was contentious. Stanton and Lincoln had both had reservations, not the least because of Harney’s age at 62, but because of his Southern heritage. In truth this proved to be more of a concern for Stanton, as Lincoln felt that heritage was not necessarily an impediment to service. Otherwise, the general was surrounded by numerous controversies.

In 1834 he had been accused of beating his sister in law’s slave Hannah to death. Though acquitted there was little doubt of his guilt. During the Mexican War he had organized the mass execution of the members of the captured members of the Saint Patrick Battalion, executing thirty men at once in a mass hanging. During the First Sioux War in retaliation for the Grattan Massacre, Harney carried out the Harney Massacre, slaughtering 86 men, women, and children[1]. Then he briefly commanded the expedition which would mount the First Utah War, before being replaced by Albert Sidney Johnson. His final great controversy would be while commanding the Department of Oregon where he escalated the so-called Pig War by dispatching troops to San Juan Island nearly leading to an all out conflict.

However, in spite of these controversies Harney was a fighter. He had shown aggression and daring while fighting the Indians in the numerous little wars across the Plains, leading them to dub him “Mad Bear” for his ruthless campaigns against them. He had shown ruthlessness and determination in Mexico commanding the 2nd Dragoons, and had shown aggressive action in Oregon in challenging the British. Despite what Stanton felt had been his ‘milquetoast’ response to early secessionist actions in Missouri in 1861, Lincoln determined he would be well acquitted to deal with the crisis developing in the South West…” - War in the Southwest: The New Mexico Campaign, Col. Edward Terry (Ret.), USMA, 1966

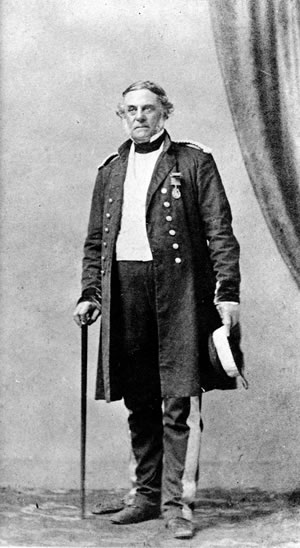

William S. Harney

“…come 1862, the Church of Jesus Christ and the Latter Day Saints had sat out the Civil War passively. The feelings from the predominately Mormon settlers of Utah thus far had been one of ‘a pox on both your houses’ as they felt warm feelings towards neither the government in Washington nor the government in Richmond. Men from both sides had attempted to assert their will with violence upon the Church.

In that territory, memories of the recent conflict in 1857 were still fresh. The Mormon Church felt that they owed little to the Federal government which had effectively made war on them, the nation which had exiled them, and the people who had denied their appeal for statehood again and again. Most Mormons would resolutely follow the idea set forward by John Taylor: “We know no North, no South, no East, no West.”…

…The war itself saw the Utah Territory stripped of Federal Troops early on, and the Mormons allowed a sort of unilateral independence of action. They, despite rumours and alarms, made no movement towards secession from the Union. They simply enjoyed their own peace while preaching judgement upon the Union. Many felt it was justice for the depravations they had suffered, while others simply saw it as a fulfillment of a prophecy that Joseph Smith had proclaimed twenty-nine years before[2].

Bringham Young himself said “God has come out of his hiding place, and has commenced to vex the nation that has rejected us, and he will vex it with a sore vexation. It will not be patched up—it never can come together again—but it will be sifted with a sieve of vanity, and in a short time it will be like water spilled on the ground.” However, when the war erupted he stated his loyalty by declaring “Utah has not seceded, but is firm for the Constitution and laws of our once happy country.”

At the beginning of the war he had maintained a stiff neutrality, seeing the whole affair as retributive justice. Though by April of 1862, he had seen that the Federal Government might not be able to reassert itself in the territory. This was both a boon, and a problem.

The local Indian tribes varied from friendly Ute tribesman, the vacillating Paiutes, to hostile Bannock and Shoshone. Though relations had been quiet at first, the absence of the army had seen the hostile tribes carry out the usual cattle raids and skirmishes with local settlers. The absence of any Federal force to deter them merely caused more opportunistic raiding. Though Young adopted a relatively benign welfare approach which attempted to trade and cultivate relations with the local tribes, the more hostile tribes approached this as weakness.

Inevitably, some sort of armed response was needed. If not to chastise the Indians, then at least to protect the settlers and government property.

This put Washington in the ironic situation of needing to ask the Mormons for help. Despite the fact they could have called on the territorial governor Stephen Harding for assistance, Lincoln was enough of a realist to realize that true power in the territory lay with Brigham Young as the leader of the Mormon church. Realizing the need for armed protection, and relishing the power he now had, Young responded enthusiastically, and appointed his first counsellor and commander of the Nauvoo Legion, Daniel H. Wells, as the adjutant-general of the territorial militia.

Though initially Washington desired only one company of cavalry, the news from the Southwest caused them to grudgingly request for one battalion of cavalry and one battalion of infantry to be formed. Though they would permit only four companies of cavalry, eight of infantry, and no artillery. The Mormons would also have to furnish their own weapons. This would provide no problems and Young was swiftly able to furnish the 1st Utah Cavalry under Col. Robert T. Burton, and the 1st “Nauvoo” Utah Infantry under Col. Hosea Stout.

This gave the state of Utah some 900 men to call on in emergency, defend Federal property, and guard the overland routes. However, the Mormons retained the territorial militia unofficially, and the Nauvoo Legion could potentially supply 8,000 men at Young’s call…

…For years Thomas Kane had served as a self-styled advocate for the Mormons in the United States. And his friendship with them, due to his personal connection to Brigham Young, never diminished. He had been one of those who said the Mormons would remain loyal. When the Civil War erupted he had enlisted with the 13th Regiment of the Pennsylvania Reserves and been badly wounded at the Battle of Dranesville. As such, he was in the capital when news of Harney’s appointment to command was related.

Kane knew that the bad blood between the Mormons and Harney ran deep, and he feared for relations if Harney were allowed to serve unchecked. He wrote to Lincoln expressing such concerns saying “No appointment could be so injurious and detrimental towards our relations with the Saints as this. Harney is a monster, filled with bloodlust. He hangs perceived traitors on a whim, and can only be counted on to deliver great misery.”

With this personal appeal to the president, he was soon brought forward to testify regarding the Mormon’s willingness to serve. He presented his case well, and the sight of this wounded warrior lobbying on behalf of their loyalty doubtless had great effect on President Lincoln. He was soon dispatched West to serve as aide-de-camp to Governor Harding, as much as to carry out the pretense of Federal control as anything else, and unofficially as Lincoln’s envoy to the Church…” The Great American War: The Mormon Experience, Kenneth Stuart, Brigham Young University, Deseret Press, 1983

Brigham Young and Thomas L. Kane

“Arriving at Fort Union, and the outlying encampments, Harney realized that he had his work cut out for him. Colonel Slough found himself in a series of running battles between Sibley’s forces and his own, with raids, annoyance bombardments, and skirmishing being the norm. Each side seemed less than desirous to declare a formal siege in desert conditions.

Making his headquarters in Albuquerque, Sibley had detached his forces so that they effectively cut the Santa Fe Trail, while ensuring that the Union could not depend on the Sangre de Crisco Mountains as a defensive position at the edge of the High Plains.

However, Sibley had grown lax come May. Though the exact reasons why may be argued about forever, it appears his supply situation was not adequately looked to, and so the short, sharp raiding actions and blocking a Union counteroffensive, seemed the best he could do. While others would blame the inaction on a drinking problem (something Sibley would deny until his death) the supply problem is feasible. Keeping his 2,000 men in the field proved a difficult task, and in the harsh desert conditions horses would be winded and broken, skirmishes with opportunistic Indians was a constant, and finally water was always at a premium, the threat of simple death from the elements was very real. With these problems, it is hardly any wonder neither side had gone looking for a general engagement.

Harney’s arrival changed all that.

His first task was to gather his forces and supplies for a campaign. The war had become an Indian war he observed, and he meant to fight one. He knew that the Confederates were scattered ‘like Indians in their camps’ and so meant to deliver a blow to them not unlike the one he had delivered to the Sioux so long ago. He gathered with him a provisional cavalry battalion with the six companies of US Cavalry, one of Colorado Cavalry, and another of Utah cavalry under Maj. Roberts as the Provisional Cavalry Battalion. As well as the 2nd Provisional Artillery Battery under Captain Claffin. To strengthen his infantry he attached the 5th Battalion US Infantry and the 1st Colorado Volunteer Infantry Regiment under Maj. John Chivington who were led in an ad hoc brigade under Slough.

Left behind to defend Fort Union would be the 1st Provisional Artillery Battery, the 4th and 1st New Mexico Volunteer infantry. He had heard the reports of their comrades conduct at Valverde and so refused to let them participate, much to the annoyance of Carson.

The plan of attack was simple. The Confederates were concentrated at three key positions, Glorietta Pass, Pecos on the Pecos River, and on the Glorietta Mesa where they issued forward to raid the supply lines for Fort Union. The most important of these positions were at Glorietta Pass and on the Mesa, as Pecos was little more than a fortified picket post. Harney determined that first the raids must cease, and dispatched the Cavalry (and a battery of horse guns) under Roberts to raid the camp.

On the morning of May 28th, having crept up the sides of the hill with the majority of the US regulars dismounted, Roberts opened his attack on the camp. At the camp were the men of the 4th Texas Mounted Rifles under Col. James Riley, as well as a battery of captured Yankee guns. The dismounted troopers caught the sleeping Confederates unawares, and the camp was soon in an uproar as the camp guards exchanged shots with the Union raiders.

Though in such a tight skirmish the fight could have swung either way, Roberts had an ace in the hole. The Utah Cavalry company under Captain Lot Smith had been directed to take their mounts up the mesa and surprise the Confederates from behind. Smith’s hardy frontiersmen and their mounts performed admirably, charging down the slope and routing the shocked Texans who made a beeline for Glorietta Pass. All told Roberts suffered some 7 men dead or wounded while killing or capturing over 80 Texans…

…by the time it came to move down to Glorietta Pass, Col. Green had been alerted to the flanking maneuver being attempted. He commanded the 5th Mounted Rifles, as well as two companies from the 2nd, and a Company from the 1st as well as Wood’s Battery of artillery. He called back the remaining companies picketing Pecos and their guns, and returned them to his positions in the Valley. He would not withdraw without a fight.

He had his troops drawn up along Glorietta Creek, with a strongpoint at Pigeon Ranch, where the guns were drawn up. His 5th was placed in the center, smattered with some refugees from the 4th Texas. The men of the 2nd and 1st were placed along the flanks, covering the high places and most prominently at Sharpshooter Ridge. Green expected the Federals would attempt to flank him, and so meant to ensure the high places were defended.

Slough advanced into the Pass with Roberts cavalry in the lead, the 5th US Infantry in the center, and the men of the Colorado Volunteers on the flanks, looking for suitable places on the high ground.

The battle opened with shots exchanged between sharpshooters, and Green’s guns soon opened up on the blue clad infantry. Slough had his own guns positioned and they began a bombardment of Pigeon Ranch. This ineffectual skirmishing continued for roughly two hours by most combatants accounts, while Slough was waiting for the men of Chivington’s regiment to gain the high ground.

Chivington did not disappoint. His troops on the right were soon trading fire with the men of the 2nd Texas, and in half an hour a vicious melee was soon erupting for control of these high places. However, Chivington’s men had the numbers and soon the Confederates were driven out, and falling back up the creek.

Green, seeing his flank about to be turned, did what he had done at Valverde, attacked. The men of the 4th Texas mounted and charged towards the 5th United States Infantry. Though as before, this briefly caught the Union off guard, Green was soon taking fire from two sides, and his troops could not force the regulars out of position. Charging three times, Green finally bowed to the inevitable, and ordered a retreat…

…after the rearguard action at Johnson’s Ranch, Sibley was properly notified of the actions at Glorietta. Reluctantly he gathered his supplies and ordered a retreat from Albuquerque, with the bulk of his remaining men retreating to Fort Craig, but a rearguard taking up a strong position at La Jolla.

By July the two sides had settled down into a position which would last for some time as Harney soon had other problems…” - War in the Southwest: The New Mexico Campaign, Col. Edward Terry (Ret.), USMA, 1966

The fighting at Glorietta Pass would decide the campaign in the Southwest in 1862

“The passage of the Morrill Anti-Bigamy Act on July 9th 1862 was seen as a deliberate snub to the Mormon Church. As such it was looked at with outright revulsion and another attempt at persecuting the Saints…

…Lincoln of course had to offer this to his party as it ran on the program of eliminating "those twin relics of barbarism - Polygamy, and Slavery" which were seen as issues in the West. Wisely, Lincoln allocated no funds to it, and ordered Governor Harding that no measure should be taken to enforce it. However, the damage had been done, and Young would demand the return of all Utah Volunteers to the territory.

This instantly began a row with Harney, who threatened to imprison any Volunteers following the ‘illegal orders’ of Young. Lot Smith’s unfortunate cavalry company would end up trapped in the middle. Smith wrote to Kane, requesting he be placed under his command, while Kane realized he could not issue such an order. In the end, Lincoln would be required to intervene and ordered Smith’s company back to Utah Territory. Harney would have one last revenge though, ordering the Utah men to be escorted back by the First Colorado Infantry under Col. John Chivington who would ‘work to help police that territory in accordance with the laws of the Federal government.’…

…though no blood was spilled and Chivington’s men would reoccupy Fort Floyd (then renamed Fort McRae) the tension in the territory rose perceptibly…” The Great American War: The Mormon Experience, Kenneth Stuart, Brigham Young University, Deseret Press, 1983

-x-x-x-x-

“By September of 1862, the fighting between the Dakota and the settlers on the frontier in the Dakota Territory. The violent uprising begun desperate and starved Dakota under Little Crow, attacking settlers and soldiers alike, had ended in failure. Over 500 were interned. By the time Buell arrived to take charge of the territory, he had been obliged to enforce military rule on the territory to prevent simple reprisal killings. A rough mixed brigade of Territorial militia and Minnesota and Wisconsin Volunteers, and men of the 4th United States Cavalry had finally defeated his troops at Wood Lake.

With the end of the fighting however, not all the hostiles were defeated, and many would take the opportunity to flee over the ‘Medicine Line’ across the border into British governed Rupert’s Land. Little Crow himself, and a few of his followers, had fled north. It was variously estimated between 100-200 ‘hostiles’ had fled across the nominal border, and might seek refuge with the British at Fort Garry.

Buell considered this unacceptable. Throughout the winter he would write to Washington declaring that “In the interest of continued peace and security along the frontier therefore, it is my proposal to use the force available at my command to move northwards and, owing to the present state of war between this Government and the Government of England, occupy points north of Pembina. We should then take possession of Upper and Lower Fort Garry, ending not only the Sioux threat, but the threat of any interference from the British authorities there.”

Though the area was largely making due with its own resources, Lincoln and Stanton could see the sense of de-facto controlling all British territory between Lake Superior and the Rocky Mountains and so would authorize what would become known as the Red River Expedition…” – War in the Northwest, Alan Cook, Friedrichsburg State College, 1971

---

1] The Battle of Ash Hollow

2] This is actually true. See Doctrines and Covenants Section 87: 1

In a two fronted war where your national survival is at stake maybe angering the one group that covers the major east-west route isn't such a great idea. Sibley is probably going down because he's a lousy commander, but Harney might alienate everyone around and the CSA might eke out a win in spite of themselves. The Red River expedition is going to be a bloodbath though. the Buffalo Wars showed how vicious all the groups all on the northern plains got when push came to shove and the Union is going to find out the hard way what that entails.

In a two fronted war where your national survival is at stake maybe angering the one group that covers the major east-west route isn't such a great idea. Sibley is probably going down because he's a lousy commander, but Harney might alienate everyone around and the CSA might eke out a win in spite of themselves. The Red River expedition is going to be a bloodbath though. the Buffalo Wars showed how vicious all the groups all on the northern plains got when push came to shove and the Union is going to find out the hard way what that entails.

Push comes to shove in a bad way in the future, let me just say. The events here will have ripple effects down well past the war! The fact that the Confederates are currently winning in Indian Territory is a pain in the neck for the Union too.

Personally I'm just glad I can call something north of the border the Red River Expedition

Chapter 42: Across the Continent Pt. 2 On the Shores of the Pacific

Chapter 42: Across the Continent Pt. 2 On the Shores of the Pacific

"Fifty-four Forty or Fight!" – Political slogan from 1846

"Starkly contrasting the truly titanic battles raging on the eastern face of the North American continent, those which took place on the Pacific Coast were relatively minor. Comparisons are often drawn to the British actions in the Russian War in the Pacific or the Baltic, and in terms of men, materials, and strategies involved, these are rather apt analogies.

The British presence in the Pacific was small, stretched between China, Australia, and various bases from the Horn of Africa to North America. The greatest commitment being three regiments in New Zealand for the purpose of keeping the peace between the Maori and the British settlers on the islands. Otherwise three battalions were also engaged in China against the threat of the Taiping rebels who menaced the important trade port of Shanghai. The British presence on the West Coast of the North American continent was even less than that, with the forces there numbering only some 130 Royal Engineers in the colonies proper and some 150 Royal Marines on station with the Pacific Squadron.

The two British colonies of Vancouver Island and British Columbia had between them roughly 51,000 inhabitants, nearly half of whom were migratory workers and claims stakers searching for gold in the foothills and river valleys of British Columbia. The settled populations were concentrated in the coastal regions and fertile valleys, with the colonial capital of Vancouver, Victoria, having the largest population at almost 5,000 souls. By contrast, the settled population which made up the American Department of the Pacific (the modern states of California, Oregon, Nevada, and Franklin) was over 450,000, with 380,000 in California alone. The great American port of San Francisco boasted a population of 57,000 citizens.

The Americans had a much larger force to draw upon than their British adversaries with some 4,600 men stretch across the Department of the Pacific, but these were largely tied down in various postings and keeping law and order across the lawless regions or skirmishing with Amerindian bands in the interior. To be fully effective these forces would have to be concentrated at a focal point, while further volunteers would need to be called upon to fill the gaps left by a withdrawal of the regulars.

While the Americans boasted a greater concentration on land at sea the story could not have been more different. The American Pacific Squadron operating from Mare Island had at its disposal only seven warships, and only three modern steam sloops, two paddle sloops, and two sail sloops. In contrast the British had three steam frigates, three screw corvettes, two screw sloops, two paddle sloops, two gunboats, as well as one sail sloop, for a total of 13 warships. Clearly the early edge rested with the Royal Navy.

Commanding these various elements were a series of capable officers and civilian administrators.

On the British side the colonial government rested in the hands of Sir James Douglas, the son of a Glasgow merchant and planter and of mixed race (though he appeared majority white) was a career fur trader who had worked his way up from the bottom rungs of the Hudson`s Bay Company as a trapper and clerk to become the governor of the colony, having practically chased his predecessor from his position. Despite the presence of an elected Legislative Assembly all practical power rested in the hands of Douglas, who was an appointee. He was very protective of his position as the colonies senior administrator and ran the colony with a tight fist while governing British Columbia mainly from Victoria, earning derision from his detractors as though he was running the colony like a ‘family compact’, especially on the mainland.

Commanding the landward forces available to the British was Colonel Richard Clement Moody as the head of the British Columbia Detachment of the Royal Engineers. Moody, a career officer, educated at Woolwich had been posted on various duties throughout Britain`s colonial possessions, mainly in the West Indies and the Falklands and a tenure as professor of fortifications at Woolwich. He had been appointed to lead the British Columbia Detachment of 150 Royal Engineers[1] as well as chief commissioner of lands and lieutenant governor of British Columbia in 1858. Commanding the Royal Navy’s Pacific Squadron was Rear-Admiral Thomas Maitland. He had entered the navy in 1816 serving in postings throughout the empire, and had served in the First Anglo-Chinese War as Captain of the flagship Wellesley in 1837. He then moved on to command the RN gunnery school aboard HMS Excellent from 1854-1857 before coming to command the Pacific Squadron aboard the steam frigate Bacchante.

Sir James Douglas

Commanding the Department of the Pacific south of the 49th parallel was the sixty year old Brigadier General George Wright. A West Point graduate Wright had served in combat against the Seminole and in the Mexican War earning distinction at Molino del Rey afterwards where he was promoted to colonel. He had served on the West Coast since 1855 and was promoted to Brigadier of Volunteers on the recommendation of his predecessor Edwin Vose Sumner upon Sumner’s return to the East. Now commanding the unified Department of the Pacific his main duties were protecting the frontier, keeping watch on secessionists, moving troops eastwards, and safeguarding the coasts. In this last duty he was aided by Flag Officer John B. Montgomery commanding the Pacific Squadron. He had served in the previous conflict between the British from the early days of the conflict and during the Mexican-American War had captured the town of Yerba Buena without a shot being fired. He had commanded the sloop of war Portsmouth and the steam frigate Roanoke before being promoted to command of the Pacific Squadron in 1859. Beneath him was Charles H. Bell another 1812 conflict veteran who had served on Lake Ontario, who would command the defensive squadron in the Bay when Montgomery moved ashore.

When war erupted in February, the telegraph hummed and the commanders on the Pacific slope were soon alerted to the dire news. Montgomery first sought to concentrate his available ships in defence of the city of San Francisco. He, Wright, and Bell, all realized it was the only real strategic objective on the western coast and were quick to call on their available resources to defend the city.

In the Department of the Pacific there were only some the majority of the available troops were pulled back to San Francisco, while Governor Leland Stanford sought Federal assistance to raise further regiments of Volunteers for service…

.jpg/220px-George_Wright_(Army_General).jpg)

Wright, Montgomery, and Bell

…Wright correctly assumed that any attack on the Pacific slope would be, by necessity, aimed at San Francisco. With the Mare Island Navy Yard, the Benicia Arsenal, and the gold reserves, it was a natural target. To defend the city four companies of the 9th Infantry Regiment was moved from the North West overland to San Francisco, with some companies of local volunteers replacing them. In San Francisco the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 5th regiments of California Volunteers were concentrated, while the 4th Regiment was posted along the frontier at Fort Yuma. Two further regiments (the 6th and 7th) were being trained and organized through the spring…

…The British meanwhile could call on only the company of Royal Marines at San Juan Island (which was bloodlessly annexed in April) and the detachment of Royal Engineers in British Columbia under Moody, whose numbers were 134 present for duty. However, even with the Marine companies from the fleet, this meant there were only some 300 regular troops available for immediate service without calling further on the resources of the Royal Navy.

To augment these forces Douglas called upon the volunteer companies of both Victoria and British Columbia. In Victoria, three companies of militia existed, the Victoria Pioneer Rifle Corps under Captain Miffin Gibbs, the Volunteer Rifle Corps under the elected Lt. Col George L. Foster, and a ‘battery’ of volunteers without guns under Captain Edgar Dewdney. On the mainland a smaller corps of Volunteers had been organized as the New Westminster Volunteer Rifles under Major Charles Drew. Douglas also placed some 50 ‘Victoria Voltiguers’ on duty, these were local ‘half-breed’ volunteers armed with company rifles and put under Douglas’s personal command.

These forces had been armed with 500 Brunswick Rifles shipped in June of 1861 in response to the worries of war in 1860. However, Douglas soon lobbied for a shipment of 1,000 modern Enfield Rifles, which was despatched by August. While these troops would be capable of securing Victoria and points on the border at New Westminster, they were, in the estimation of the men on the ground, incapable of offering a defence against a determined assault by Union forces along the whole of the frontier.

Douglas however, had a plan. Writing to the War Department he would suggest: “The Naval Force at present here, consists of Her Majesty's steam Frigate "Topaze", Captain The Honble J.W.S. Spencer; the "Hecate" Surveying Ship with the "Forward" and "Grappler" Gun Boats. With the exception of the Forward, whose boilers are worn out and unserviceable, these Ships are all in a thoroughly efficient state.

Our Military Force consists of the Detachment of Royal Engineers stationed in British Columbia, and the Royal Marine Infantry occupying the disputed Island of San Juan; forming in all about 200 rank and file.

The United States have absolutely no Naval Force in these waters, beyond one or two small Revenue Vessels; and with the exception of one Company of Artillery, I am informed that all their regular Troops have been withdrawn from Oregon and Washington Territory; but it must nevertheless be evident that the small Military Force we possess, if acting solely on the defensive, could not protect our Extensive frontier even against the Militia or Volunteer Corps that may be let loose upon the British Possessions.

In such circumstances I conceive that our only chance of success will be found in assuming the offensive and taking possession of Puget Sound with Her Majesty's Ships, re-inforced by such bodies of local auxilliaries as can, in the Emergency, be raised, whenever hostilities are actually declared, and by that means effectually preventing the departure of any hostile armament against the British Colonies, and at one blow cutting off the Enemy's supplies by sea, destroying his foreign trade, and entirely crippling his resources, before any organization of the inhabitants into military bodies can have effect.”

British ships at Esquimalt

Since the abortive “Pig War” of 1859, there had been disputes over how to handle the Pacific slope of North America. The Admiralty insisted that any diversion of troops from China or India was pointless as the Fleet could more than adequately protect Britain’s holdings there in light of their advantage over the American Navy. While Palmerston would view it as necessary to move some force across the Pacific to properly combat the Americans on that far front. The debate would rage well into January, but finally it was decided in March that a battalion should be detached from China as, at the very least, a holding measure. If further operations were to be required other troops could be moved.

The 99th Regiment of Foot was moved across the Pacific in late March, arriving in Victoria on May 21st 1862. An extra 800 men gave the British a decisive advantage in manpower in the region, as south of the border the Americans were in desperate straights.

Though the state government of California had been able to call upon further volunteers, the state of Oregon and the Washington territory were lacking the resources necessary to create a viable defence, much less call out whole new regiments of volunteers. While in June of 1861 there were 145 weapons issued to regional militia companies in the territory, only some 288 remained in the hands of the territorial government in Olympia. Wright determined that some form of organization should be appointed in that territory, and the commander, Col. Justus Steinberger, worked to enroll and arm the six existing companies which had expressed interest in service.

However, even with the enrolled Volunteers, and the few remaining companies of regulars under Col. Albermarle Cady and the overall Brigadier General Benjamin Alvord, they were hard pressed to concentrate their forces in any decisive manner.

Brigadier Alvord had been personally selected by Wright to command the District of Oregon (which encompassed the state of Oregon and Washington Territory) because Wright desired that the large district be commanded by an experienced officer. Alvord had served with the 4th Infantry Regiment since 1833, and had fought in the Seminole Wars and the Mexican Wars. He expected that there would be trouble with the British or the Indians, and so was prepared to do all he could to defend the territory.

He and Wright both recognized that the Puget Sound and the Columbia River were natural entry points for an invading force. Both sites were essentially defenceless against the descent of a single steamer, and the important fortifications at Fort Steilacoom and Fort Vancouver were deemed ‘not prepared for defence against heavy guns’ making them all to vulnerable to the British ships at sea.

While Alvord would do his best to defend against the British, he could expect no help from the navy. Montgomery’s first act upon the outbreak of war had been to recall his scattered squadron home from its posts across the Pacific. Bell himself had been with Lancaster off Panama when the order for American ships to concentrate had come in early February. He had returned north to San Francisco, and sent orders for his wayward vessels, Narragansett and Saranac to return home. Saranac was able to return without issue, while the unfortunate Narragansett was caught off Panama by the concentrating British squadron, and captured. That left only the sailing ships Cyane and St. Mary’s which Bell deemed unfit for service against the British squadron. Though he hoped they might cause some damage as commerce raiders, he swiftly raided their armament to outfit other vessels and manhandle a number of guns into shore positions.

Though both ships would sail as commerce raiders, it would be the three vessels taken from the Pacific Mail company that would earn the most acclaim in the Pacific…

…Outfitting other vessels for service proved difficult. The Navy was in search of ships, but many were being sold for outrageously high prices or would require exorbitant costs to fit out for warlike purposes. For instance, the vessel which would become the USS Hermann would cost 105,000$ to purchase and outfit for use by the Navy. Even as prices were soaring across California both from the devastating winter floods, and with the rise in the cost of greebacks, this would see over 500,000$ spend on naval defence alone.

The squadron under Maitland faced similar hurdles. On the outbreak of war Maitland had only the vessels Topaze(51), and the gunboats Hectate(4), Grappler(4) and Forward(4) based at Esquimalt, though they would be joined by the steam transport Vulcan(6) and the corvette Pearl(21). His flagship Bacchante(51) was at Panama, where she would be watching ships coming and going.

The remaining ships of the squadron, the corvette Termagant(21) at Callao, the sloops Cameleon(17) and Mutinie(17), the paddle gunboats Devastation(6) and Geyser(6) which had been dispatched from Britain in late January along with what would become Maitland’s new flag the liner Waterloo(89) and the frigate Undaunted(51).

Maitland would transfer his flag to Waterloo in early May, while in mid-March the vessels Termagant (replaced by Mutinie at Callao), Cameleon, Topaze, and the gunboat Devastation were initially dispatched to blockade San Francisco. With the arrival of further ships, Maitland brought Waterloo and Geyser to the blockade while Undaunted and Termagant were sent hunting the American raiders which had evaded the blockade across the Pacific…

…an assault on San Francisco would require further resources than those to hand, but Douglas’s letter to London in December. An action to seize the Washington territory was seen as a viable way to draw off Union troops for further efforts at raiding or occupying portions of the American coasts.

The 99th Foot was seen as the obvious choice to lead an assault, aided by a smattering of Royal Engineers, Marines, and sailors turned gunners. The plan was to have Pearl escort the transport Vulcan alongside a number of smaller steamers pressed into service with the gunboats Forward and Grappler alongside. They would land the 99th who would then proceed to occupy Olympia, in preparation, potentially, for a march overland to Portland and the line of the Columbia River.

Alvord, for his part, had only a token force to protect Olympia. At Fort Steilacoom there were some 150 regulars of the 4th Regiment and attached artillery, while at Olympia two companies of the 4th and the putative force of the “1st Washington Volunteer Infantry Regiment” undergoing training, alongside a green battery of artillery with two howitzers, totalling only 250 men. Alvord had two more companies of regulars at Fort Vancouver, but the remaining militia (four ad hoc companies) were scattered across the interior guarding settlers and chasing Native bands. No reinforcement from California or Oregon had been forthcoming, and by June this was all that was available to defend the territory.

The force defending Olympia overall was under the command of Col. Cady alongside militia Major Charles Rumrill. Both men had done what they could to defend these points, but overall they were outmatched. Earthworks were roughly thrown up and the few guns positioned. So when on June 22nd reports of British steamers steaming up the Puget Sound came in, both men did what they could.

The force led by Pearl under the command of Captain John Borlase steamed towards Fort Steilacoom, which was discovered abandoned, Cady having marched to Olympia rather than holding an untenable position at the fort. Detaching a company of the 99th to hold it, the British force continued south down the Sound. Anchoring at Butler Cove, the British vessels bombarded the earthworks. Despite some sharp shore fire, the guns were soon dismounted, and smoke rose from the town.

The gunboats led the landing of the shore parties of the 99th under Lt. Col. George M. Reeves, pounding up the surf and into the town. Despite an hour of intense fighting, the outcome was never in doubt. Though Cady’s 400 men fought bravely, the 900 men put into the field by the British was overwhelming. Cady’s men would fall back overland to Cathlamette, while the Union Jack would be raised over Olympia. The British had won their first strike on the Pacific Slope…” - The World on Fire: The Third Anlgo-American War, Ashley Grimes, 2009, Random House Publishing

Last edited:

Part of me wants some duffer in the Colonial Office to make the mistake of detaching some of the forces in New Zealand, to give Te Kooti a bit more of a fighting chance.

Will there by any volunteer companies from New South Wales and Victoria, as there were in OTL's Sudanese expedition? Actually, will the large numbers of Americans on the Australian goldfields cause any tension?

Will there by any volunteer companies from New South Wales and Victoria, as there were in OTL's Sudanese expedition? Actually, will the large numbers of Americans on the Australian goldfields cause any tension?

Part of me wants some duffer in the Colonial Office to make the mistake of detaching some of the forces in New Zealand, to give Te Kooti a bit more of a fighting chance.

All bets are off here as British forces are shuffled about for the big show in North America! Though we shall see how New Zealand goes...

Will there by any volunteer companies from New South Wales and Victoria, as there were in OTL's Sudanese expedition? Actually, will the large numbers of Americans on the Australian goldfields cause any tension?

Well, with American raiders running across the Pacific the colonists in Australia and New Zealand are going to have a big impetus to form some units for self defence. I think that the British will also be keen to call on their help if things go haywire in the other theaters they have in the Pacific.

Chapter 43: 1862 A Year in Review

Chapter 43: 1862 A Year in Review

North America:

President Lincoln signs into law the Pacific Railroad Acts, the Homestead Act, and the Morrill Land Grant Act.

May 5th – French forces are defeated at the Battle of Puebla

“Napoleon had dispatched 6,500 soldiers to Mexico commanded by the Count de Lorencez, Charles Latrille. Lorencez was the scion of a minor noble family born in 1814 he had studied Saint-Cyr and graduated in 1832, earning the rank of colonel after service in Algeria. He fought in the Crimea, fighting in the successful French assault on the Malakoff Redout earning his rank as a major general. He held the Mexican forces in ill-regard writing that his men were “…so superior to the Mexican in terms of race, organization and moral discipline that now at the head of 6,000 soldiers I am the master of Mexico.”

Using the excuse of yellow fever amongst the low lying hot lands around Veracruz he opted to move his men inland to the higher plateaus at Orizaba early in January. In reality he was positioning his forces for a march on the important city of Puebla, which controlled the road to Mexico City. In early May he marched his men inland along the winding roadway where he was joined by the Conservative general Leonardo Márquez and some 2,500 Conservative troops. He then marched on Puebla.

Puebla was defended by only some 4,500 Mexicans under the command Ignacio Zaragoza, long-time supporter of the Liberal cause with experience from the internecine conflict of the 1850s. His command was comprised of regular troops, local irregulars, and local villagers armed with a wide variety of weapons. It seemed as though the outcome could only go one way. However, Lorencez was supremely overconfident deciding to ignore advice from Márquez and attack the Mexican position head on, without the support of his Mexican auxiliaries.

The Mexican position was strong, circled by a series of entrenchments and forts. Lorencez had decided to attack a position from the north where two forts, Loreto and Guadalupe, sat on two hills above the main ground. These formed a natural ‘saddle’ of land which funneled the French troops directly into the sites of the Mexican gunners. Lorencez opened the assault with a two hour artillery bombardment, wasting almost all his ammunition as his guns were unable to depress enough to hit the hilltop Mexican positions, and consequently the French infantry would advance without support. The first assault was driven back with heavy casualties. Two further waves were also driven back. At this time though, further Mexican reinforcements arrived from the interior, tripling the Mexican numbers. Lorencez was compelled to ingloriously retreat pursued by Mexican cavalry under Porifio Diaz. The French had suffered some 700 casualties, while the Mexicans had lost only 200 men.

It was a great victory which caused a day of celebration in Mexico becoming a day celebrated the liberales radicales…

…Napoleon was greatly disturbed by the news, as well as the dawning realization that the war in North America would not be short or easy. The French public was incensed, and demands for revanche in North America were printed in the presses all around France.

Napoleon then found himself in a difficult position. To not respond would be a slight on French national honor, while losing prestige abroad. In order to properly respond though would require a significant investment of resources in North America beyond what France had already deployed. Admiral Jurien de La Gravière, in charge of the squadron in the Gulf of Mexico, was recalled to explain the lack of French preparedness in the region Gravière requested reinforcement which he was granted, receiving further six ships including the ironclad Normandie.

However, Napoleon also needed to consider his relations with the North. The Confederate minister in Paris, John Slidell, had been officially received by the Emperor, but despite repeated prodding he had not yet offered official diplomatic recognition, which was resisted by his foreign minister Edouard Thouvenel. Increasing strains between Napoleon and his foreign minister resulted in Thouvenel’s dismissal in July and his subsequent replacement by the more Southern friendly Edouard Drouyn de Lhuys. Lhuys personally entertained Slidell on a number of occasions and began making tentative gestures towards diplomatic recognition.

In the short term he offered considerable work towards French material aide, facilitating meetings with French bankers and the shipwright Lucien Armand…” – The Mexican Adventure, Marc Braudel, 1986

The Battle of Puebla

South America:

September 10 – Francisco Solano López is appointed 2nd President of Paraguay.

Europe:

March – Victor Hugo publishes Les Miserables.

June 7th – The Tsarskoye Selo Letter (Selo Letter) is written.

“Though only found upon the opening of the Russian Archives in the 1970s, the Selo Letter has been a cause of considerable debate amongst Russian historians ever since its discovery. Tsar Alexander writing privately to the Swedish King Charles XV made a serious of, to many, frankly baffling assurances regarding Swedish interests in the Baltic. In light of their decidedly pro-Allied stance in the late with Britain and France the Tsar’s statement that “we would have no designs on Swedish land and no objection to Sweden’s ambitions” seems nearly suicidal.

Most modern scholars believe that Alexander was, at the time, trying to ease tensions with his Baltic neighbors and sow dissension amongst potential British allies in the region. A softening of relations with his neighbors. It seems his only reason for attempting such was British distraction in North America. Had he known all the consequences this letter might have, he may not have bothered writing it at all…” – The Late Baltic Powers, Ian Branagh, Oxford, 1991

September 22 - Otto von Bismarck becomes prime minister of Prussia, following refusal by the country's Landtag to accept the military budget. He begins working with Von Roon in efforts to force through a new reform of the Prussian military.

October 23 – Otto is deposed as King of Greece. This causes significant panic in London, fearing it will bring up the Eastern Question once again. Ships and soldiers meant for the North American warfront are instead dispatched to Malta.

November 20th – Parliament approves the earmarking of funds for the raising of 20,000 new men for the army, adding second regiments for the 26th through 36th Regiments of Foot.

The Expulsion of King Otto

Asia:

April 13th – The French gain concessions from the Nguyen dynasty in the territories of of Biên Hòa, Gia Định and Định Tường. This will become Cochinchina in the French colonial empire. Guerilla leader Trương Định refuses to recognise the concessions and later treaty.

September 14th – The Namamugi Incident. Merchant Charles Lennox Richardson is killed by retainers of the daimyo of the Satsuma clan after wandering into a procession of the lord of the domain. He was hacked to death by the daimyo’s bodyguards shortly after supposedly uttering “I know how to deal with these people.” The British demand compensation for his death, but the Satsuma decline to pay.

September 20th - Battle of Cixi. Frederick Townsend Ward leads the 5,000 men of the Ever Victorious Army against the Taiping Stronghold threatening Shanghai at Cixi. With modern rifles and artillery (and aid from British gunboats) he drives the rebels from their stronghold in a day’s hard fought action. He will continue leading the army north into the new year.

Frederick Townsend Ward, leader of the Ever Victorious Army

And we finally get to the beyond portion of things a bit!  This ends off 1862, so now I shall begin feverishly working on 1863!

This ends off 1862, so now I shall begin feverishly working on 1863!

So here's a big question for readers, where would people like me to start off in 1863? My narrative updates in January are set, but where would you most like to see in the early winter phases for an update? Spring-Summer 1863 is locked in for now, but February-April is fairly loose, so my question is where do you want to go in that time?

Threadmarks

View all 158 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 126: The Balance of Power in North America Chapter 127: What If? Chapter 128: 1866 A Year in Review Chapter 129: Grasping at Thrones Chapter 130: Plots in Motion Chapter 131: Trans-Atlantic Troubles Chapter 132: A Want of Preparation Chapter 133: Alarms Ignored

Share: