OK, let's try this again. This time I'll go in chronological order, so I'll start again from the PoD. In this first installment, there's little new material: the second chapter is largely a rewriting of what I already posted, in a style closer to the rest. I'm writing this as excerpts from a TTL world history textbook; the chapters before the PoD, as well as those about pre-contact American civilizations, have been cut.

Dates are given as BS/AS (it'll be explained at its own time) and converted in BC/AD. Most regions of Earth have different names; I'll give the OTL name between square brackets unless I think it's clear from the context or I want to leave it for later.

1. The Time of Free Ionia (414 – 360 BS)

Among the matters of greatest interest in the study of history is that of “aborted civilizations” - that is, civilizations, cultures and polities that ceased to be, after a time of promising progress and flourishing, before they could reach the peak of their capabilities. History is tragically replete with them, from the hundred native cultures of Tohoroku lost to eastern settlement and colonization to the mercantile khaganates in the heart of Asia that lost their sustenance as trade shifted to ocean routes. Climate change brought down the great Mayan civilization, growing empires destroyed the early states of the Bronze Age and the fledgling Mandé states of the Kwara. In all this cases, one can but speculate what the fate of these peoples could have been in another history – an ultimately fruitless, yet oddly compelling endeavor.

Among the most famous cases of this is the ancient culture of Ionia (Yunan), or, at it was known by its ancient natives, Hellas. This uneven land, almost a cluster of mountain ranges rising from the Mediterranean, was occupied by dozens of city states competing for territory and influence. Despite their political division, they were bound by a unified culture that was surprisingly sophisticate, including a single language, a single religion, common laws and customs. We already described their predecessors in a former chapter as Myceneans.

After the collapse of the Mycenean civilization, the Hellenic peoples migrated away from their homeland, eventually creating colonies all around the shores of the Mediterranean, from the coasts of Keltistan in the west to the Tauris peninsula in the east. They became dominant on the Aegean coast of Anatolia, as Aeolia and Ionia proper (Inner Ionia). This included Hellenic cities such as Smyrna, Sardis, Ephesus, Miletus and Halikarnassos, as well as islands such as Lesbos, Chios, Samos and Rhodes.

First unified under the king Croesus of Lydia in the 5th century BS, the Ionian Hellenes were eventually conquered by Cyrus the Great in 414 BS [547 BC]. While they still enjoyed a certain degree of autonomy under Persian rule, they were too fragmented to be controlled through their old elite, and thus they found themselves subject to tyrants appointed by the satrap in Sardis.

Among them was Histiaeus, tyrant of Miletus, who had followed the Emperor Darius in war against the Scythians. He was reportedly an ambitious man, so that Darius, to better control him, would rather keep him as advisor in Susa. To return to his powerful position in Ionia, Histiaeus found no better way than to organize a rebellion.

Through his son-in-law Aristagoras, to whom Miletus was entrusted at that time (and who had already endangered his own position by organizing a failed conquest campaign in the Aegean), he contacted the inhabitants the cities in Hellas for help. Athens and Eretria agreed to send warriors, while Sparta refused. With their help, Histiaeus and Aristagoras conquered Sardis and burned it in 365 BS [498 BC]. Most historians agree that this was a foolish act for the free Hellenes, a fight against Persia being one they were ultimately doomed to lose. In fact, Athens broke its alliance with the Ionians, but they continued to fight even as they were badly defeated at Ephesus.

The fall of Miletus to Persian forces was an omen of the fate of Hellenic cities, with its walls torn down, its population killed or enslaved, its homes repopulated by Persians. The Ionian revolt would continue for many years, but the result was already clear. It wouldn't be enough to punish the (Inner) Ionians. Their brothers beyond the Aegean had to be prevented from interfering in such a destructive way with Persia ever again.

2. The End of Hellas (359 – ca. 350 BS)

After crushing the rebels in Inner Ionia, the Persians tried to reestablish order in what was once again their land. General Mardonius, Darius's son-in-law, deposed the local tyrants and replaced them with democratic governments, of course still submitted to Persian rule. Five years after the burning of Sardis, the only thing that remained undone was the punishment for the Hellenes who had supported the rebels. So, in 359 BS [492 BC], the Persian invasion of Hellas began.

The first campaign, under Mardonius, followed both a land route through the Hellespont and a sea route through the Aegean. This campaign fully subjugated Thrace and Macedonia, paving the road for the submission of the Hellenic peninsula. However, a violent storm badly damaged the Persian fleet. Darius turned to diplomacy, sending ambassadors to the major Hellenic cities to ask the recognition of Persian supremacy. The ambassadors were executed in Athens, and thrown down a well in Sparta. It seemed rival city states were ready to cooperate against a common enemy; however, their mistrust of each other would be the seed of their downfall, both between cities and within.

Persians had on their side an exiled king of Sparta, Demaratus. With political chaos keeping Sparta busy, in 357 BS [490 BC] Darius launched an expedition towards Athens under Datis. The siege of Eretria was relatively quick, with the Persian troops marching unopposed to the walls of the city, and the doors opened by traitors after two months. The city was looted and burned, its temples destroyed and its inhabitants enslaved.

The Persian fleet landed near Athens. Messengers were sent to Sparta to call for help, but the holy period of the Carneias committed Sparta to peace until the next full moon, thus for the next ten days. It's possible that Sparta deliberately withheld help from Athens hoping in the destruction of their rivals. The Athenian army, with reinforcements from Plataea, finally marched into the plain of Marathon [1]. As they attacked, they were repeatedly hit by the arrows of Saka mounted archers. In the flat, open landscape of Marathon, the Athenian hoplites were outflanked by Persian cavalry [2] and unceremoniously slaughtered.

At this point, Athens was completely defenseless. Most, while disheartened, hoped to preserve their culture under Persian rule, as the Inner Ionian had done. But a radical faction appeared as panic grew; terrifying each other and themselves with stories of Asian cruelty that became more horrific at each retelling, they decided to deny any resource to the invaders. City states blamed each other for the failure, or simply used it as an excuse to attack their rivals. As the Persian army marched through Thessalia and Peloponnesis, rooting out the smaller armies one by one, they found farmers burning their crops and slaughtering their livestock. At Sparta, they found the women and children lying in their beds wit their throat cut, and the men impaled on their own swords.

General Mardonius sat as first satrap of Outer Ionia in Thebes, which had quickly pledged allegiance to the King of Kings. Darius chose to give the survivors a place in Persian society; those responsible for the revolt had been punished, and no more bloodshed was necessary. Still, famine swept the land, and so did disease, as refugees ran like ants from city to city – or simply out of Hellas, into their colonies in the Mediterranean, still outside the Persian grasp.

And like that, Hellas was over. Ravaged and depopulated, more by its own hand than by the invaders, it was slowly refilled by Persian immigrants. Many thousands of surviving Hellenes tried their fortunes deep in the Empire and scattered, learning Aramaic and mixing with Medes, Scythians and Bactrians. As a group, history has nothing more to say about them.

Hellenic historians have at long bemoaned the defeat at Marathon, blaming it first of all on the betrayal of Sparta, then to the premature death of general Miltiades just a few days before the battle, and then to a disease that weakened the vigor of their soldiers. The thesis of the disease may be not entirely without merit: an infection reminiscent of the black plague, which probably had reached the peninsula after the siege of Eretria, is recorded in the years of the Persian conquest of Ionia. It would have been in the interest of Athens to delay the battle until reinforcements from Sparta could arrive; the disease might have forced them to attack before the soldiers were weakened even more.

However, these factors might be ultimately without importance. The truth of the matter is that the Hellenic states had taken on an enemy that was simply too powerful to be defeated. If Darius's campaign had been turned back, another would come. However interesting it might be to speculate on a history in which Hellas remained free, such history is to be considered inherently unrealistic.

[1] Everything before now, as far as I understand, is a description of OTL history (except obviously the very first paragraph).

[2] It's not certain whether Persian cavalry was actually present at Marathon. If it wasn't, I guess the actual PoD is this.

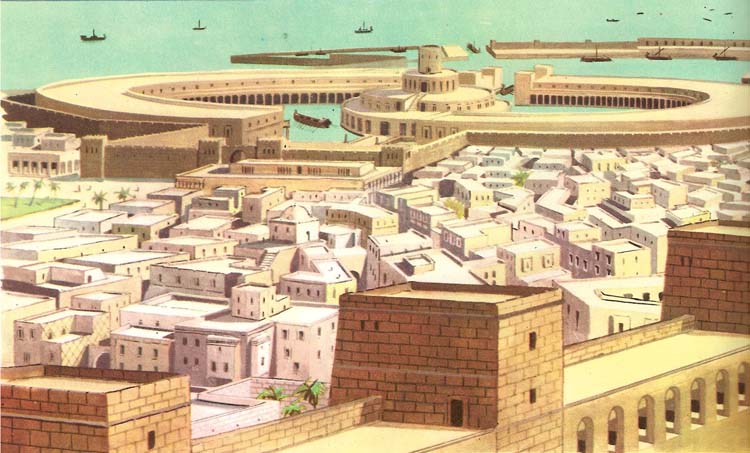

In the next installment: in the west, Carthage profits from the situation...