Ok, this is an abbreviated and condensed version of what was originally going to be three separate posts. Since they were all related, I decided to try to shorten it up and make it an simple as possible without missing the key points. This is another technical progress update more than a true narrative update. Not much is really resolved with this but it is essential to lay the ground work the for some very important changes to come--although it is not all encompassing.

10 March 1943

Wright Field, Ohio, USA

After his short skip to England to help organize the 14th, Lt.Col. Ben Kelsey had returned to the States in September to resume his primary role as Chief of the Army Air Corps Pursuit Branch where one of his duties was to coordinate development, testing, and procurement of fighter aircraft—or pursuit aircraft as they used to be called—for the Army Air Forces.

He had spent the most of the autumn at Wright Field, going over fighter contracts, performance reports, and tactical reports on the various types of aircraft under his sphere of influence. Since the United States became involved in the war there has been a flurry of development and demand for new and improved fighter aircraft. Work had increased on improving early production models of several planes such as Republic’s troubled P-47 while others were being brought up to new standards without AAF intervention, such as NAA’s P-51 which Kelsey himself had made possible through some back channel maneuvering with NACA back in 1940 by ensuring they would have access to the new studies on laminar flow wings.

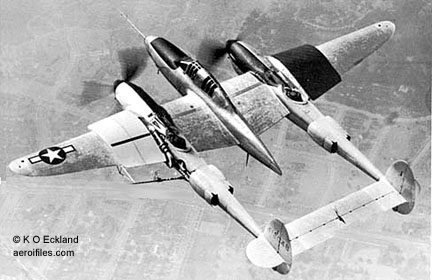

Still, Kelsey was most pleased hearing of the successes of the P-38’s as they entered combat. With the onset of Operation Torch in November and the arrival of the P-38’s of the 1st, 14th, and 82 Fighter Groups to the 12th Air Force, the overall impression has been positive with the Lightning having an immediate impact which the Germans and Italians were struggling to counter-act. The stories from Papua New Guinea were a whole other matter—according to Gen. George Kenney, CO of the 5th Air Force and with whom Kelsey had worked closely during development of the P-38, within two weeks of the P-38’s from a

single squadron joining the battle they had achieved near complete air supremacy over southern New Guinea. On their first combat alone, on December 27th, a mere 10 planes from the 39th squadron accounted for 13 claims of Japanese aircraft destroyed and one probable in the process of breaking up an attack on the American supply convoy. The squadron leader, Capt. Thomas Lynch—who together with his wingman had accounted for four of the victories—had since been recommended for the Distinguished Service Cross for his role in the action that day.

The P-38 was proving to be extremely versatile too. The F-4 and F-5 Photo Reconnaissance versions were being used to great effect in the SWPA in locating the enemy positions and providing bomb-assessment photographs with some similar uses in North Africa. Eighth Bomber Command in England was also beginning to use them for the same reasons and finding them well suited to low and mid-level reconnaissance.

The 5th AF had also made great use of the P-38 as a ground attack airplane and glide bomber. The payload of the center wing pylons were sufficient in the F model to carry up to 1000 pound general purpose bombs--although 500 GPs were far more common--and the G model could handle up to 2000 pound GPs thanks to the strengthening done to accommodate 310 gallon drop tanks. There was even some talk of creating light bomber forces of P-38’s but in order for it to be successful they would need to find a way to properly aim the bombs preferably with the aid of the Norden Bomb Sight.

Both the 12th and 5th Air Forces, as well as the 11th Air Force in Alaska and the 8th in England all reported some common complaints with the airplane—it was too complicated, had poor serviceability, and unreliable engines—plus some contradicting accounts of the cockpit being too cold or too hot. But, the biggest complaint of any of the Groups that had used the type in combat to date was simply that they did not have enough of them. The shortage was becoming so severe in the critical North African theater that yet another Fighter Group originally meant for the VIII Fighter Command in England, the 78th, had all of their P-38’s transferred over the three groups in Algeria, leaving them without any full P-38’s groups in England once more.

Kelsey would leave the problems of production to the War Production Board and Lockheed, all he could influence was the number of planes on order and already the orders had already far surpassed production capacity. What he could help with was determine better practices to increase the sortie rate and smooth pilot transition to the type.

To help Lockheed and the airmen in their respective theaters of operation, he had departed Ohio after Christmas to spend the last couple months going between Lockheed’s headquarters in Burbank and the Muroc Lake airfield complex out in the desert to run some experiments on the airplane to see just how much punishment it can actually take.

Of chief concern were the turbos and the intake manifold pressures as Lockheed had finally developed an automatic turbo-governor and was anxious to calibrate them to the best possible settings for AAF use. Using a P-38G-5-LO modified to have the throttle stops removed Kelsey had been abusing the turbos and engines as much as he could trying to find their limits in boost, temperature, and duration before failing. The airplane was not fully representative of those that would be in combat as after each test flight the engines were completely over-hauled and all the ducting was re-fitted to ensure perfect seals but, after all, he was trying to find the absolute limits and needed it to be perfect to find them.

The test engineers had installed crude turbo tachometers on the left windshield frame and turbo oil temperature gauges on the right frame. In six flights over the past two months Kelsey had beat the hell out of the turbos and the engines before finally experiencing a catastrophic failure a few days prior when running the turbos well beyond their design limits. The intercoolers had proved to be extremely efficient even at the high boost pressures in maintaining acceptable Carburetor Air Temperature but the turbos themselves were now overheating at the extremely high speeds. The failure on March 4th occurred after four minutes climbing from 12,000 feet to 22,000 feet with the turbos spinning at 27,000 RPM. He had observed Manifold Pressures as high as 70 in/Hg and could run over 64 in/Hg up to 22,000 feet with the engines running fine up to a C.A.T. of 150 degrees Fahrenheit, or about 65 degrees Celsius, before the failure occurred. Even then the failure was not in the engine due to high C.A.T. but in the turbine itself as it overheated and seized before coming apart, sending a wave of back-pressure from the engine intake and bursting the inter-cooler. The turbo-supercharger oil temperature registered at over 230°F when the failure occurred and had been running past 205°F for the few minutes prior to.

He recently heard that Colonel Cass Hough of the Technical Branch, Headquarters Division, VIII Bomber Command, had run related tests on a P-38F-1-LO he commandeered in England. Col. Hough, who was more focused on boost pressures than turbine governance, had ran 60 in/Hg manifold pressure up to about 25,000 and as much as 40 in/Hg at 40,000 feet. His airplane did not have a visible tachometer installed but Kelsey’s engineers estimated that the old B-2 turbo was likely over-speeding at well over 26,000 RPM to get those pressures and would likely fail after only a short duration at those speeds.

Based on his own tests and with keeping Hough’s tests in mind, Kelsey had sent his recommendations on to Wright Field. The AAF, however, was more conservative and down-rated his and Hough’s finding in order to provide for imperfections in the field and a little more pilot safety. In the end they were sending Lockheed the specification to keep the governors at their 24,000 rpm limit for current production airplanes but to pursue development of new upgraded turbos for future airplanes capable of maintaining Rated Military Power above 25,000 feet for at least twenty minutes with provision for a short time at an over-speed War Emergency Power setting. Failing availability of upgraded turbos, the AAF is providing Lockheed the ability to add WEP at available manifold pressure from a turbo speed of 26,000 RPM.

The secondary turbo-temperature governor was calibrated to take over when the turbo-supercharger oil temperature reached 200°F which the engineers estimated should allow enough tolerance for the turbine to slow and maintain safe temperatures without failure.

With his engine testing more-or-less complete, Kelsey had just returned to Ohio from California to discover the Final Report on the Tactical Suitability of the P-38F Type Airplane waiting for him. The report had been compiled after nearly five months of testing at the Army Air Forces Proving Ground in Elgin, Florida and it contained some pretty decent assessments of the type, comparisons to other types assessed, and re-affirmed some of the failings reported from the field.

The comparison tests were mostly favorable, concluding that the “combination of climb, range, endurance, speed, altitude, and fire power, the P-38F is the best production fighter tested to date…” with notes that the P-47C-1 was faster at most altitudes and the P-40F and new P-51 were faster below 15,000 feet but that the P-38F accelerated and climbed best of all types. Most interesting, to Kelsey, was that the P-38F could turn equal to or better than all other types above 15,000 feet but that its slow initial roll rate always put it at a disadvantage at the start of the turns against the P-40F and the P-51.

The report did call out the maintenance difficulties with the aircraft and the difficulty expected in transition training when switching pilots from single-engine types to the twin-engine P-38. The other deficiencies noted were poor cockpit layout, poor cockpit heating, and the tendency for the guns to jam in maneuvers over 3.5G’s, a problem shared with the P-47 and related to the design and layout of the magazines.

Section four of the report, which was the list of recommendations read:

4.

RECOMMENDATIONS:

It is recommended that:

a. Suitable means of maintaining cockpit heat at altitude be installed. (Cockpit heater on P-39NO is best seen to date).

b. Continued efforts be made to increase rate of climb and level high speed.

c. Automatic shutter control of carburetor air, coolant, and oil temperature be installed.

d. One (1) gun switch be installed for all guns, eliminating the separate machine gun button and retaining only safety switch.

e. The generators and battery switch be incorporated with the master switch and the booster pump’s switch incorporated with the individual engine switches.

f. The rate of aileron roll be increased.

g. The case ejection chute control be removed from the cockpit.

h. Elevator trim be moved to rear nearer the pilot for more accessibility. (Ideal arrangement in P-51 airplane).

i. The offset control be replaced by a straight control column in the middle of the cockpit, if possible. If not, the control column be reduced to a minimum safe size to increase visibility of the instrument panel and save space in the cockpit.

j. Until the automatic turbo governor is installed, a turbo tachometer be added to the instrument panel.

k. The energizing and starter switches be placed next to the main motor switches. Also all other switches that have to be used either for starting the engines or during take-offs be grouped together. These switches should be placed in a horizontal row, “off” when down and “on” when up. A drop bar should be placed below this so all switches could be turned on when the bar is lifted, after which the bar will drop back down.

l. The toggle switch type of primer (Stromberg Electric Priming Valve-T.O.-03-10BA-25) be installed for ease and speed of interception work.

m. The starters be of such a type that both engines may be started at the same time for interception work.

n. Only one (1) landing light of a stationary type be installed on the leading edge of the left wing.

o. The gun sight be of the type which will accommodate a 100 mil circle, permit bulb replacement in flight and reflection adjustment for low level bombing.

p. Paddle blade propellers be incorporated in the P-38 design to improve climbing capabilities.

q. A gun sight be installed that will allow the 161 mil view over the nose to be used in deflection shooting. (Current sight only allows 58 mil view down).

Reviewing the recommendations, Kelsey noted that several were already being explored and developed by Lockheed including the automatic shutter control and the use of paddle-blade propellers. The rather vague recommendation of continuing efforts to “increase rate of climb and level high speed” was a bit of mystery because it seemed rather redundant with standard practice and those performance factors had already been improved with the P-38G which was not part of the test. In fact, based the companion report from the P-47C-1 testing and the unrelated Performance Acceptance Report from a P-38G-5-LO the previous month, Kelsey could see that already the new P-38 was faster than the P-47 above 20,000 feet and would imminently better suited to the long range, high-altitude patrol and escort if they can get the issues with pilot comfort worked out.

The issue with the cockpit heat would need to be forwarded over to Lockheed and Kelsey could only hope they would be able to take a look at the P-39 and create a similar system for the P-38. The same applied to all of the other recommendations relating to the cockpit layout and functionality of specific controls. He could certainly get behind the recommendation to replace the manual engine primer with the automatic one as currently, starting the engines on the P-38 was a three-hand job for a two-hand pilot.

The problems with the guns can be worked on by the AAF itself in Muroc where they can do field modifications and gunnery tests until they get it right and can then fly the modified plane back to Burbank so Lockheed can change make adjustments to the line.

Similarly, the issues with the gunsight is one for the AAF, not for Lockheed and Kelsey would be sure to procure a few examples of current and development model gun-sights from the Air Corps, Navy, and anything he can beg from the RAF to try fitting in the Lightning until they find the best fit.

In the meantime, he was left to write up his orders for Lockheed and prioritize the recommendations.