raharris1973

Gone Fishin'

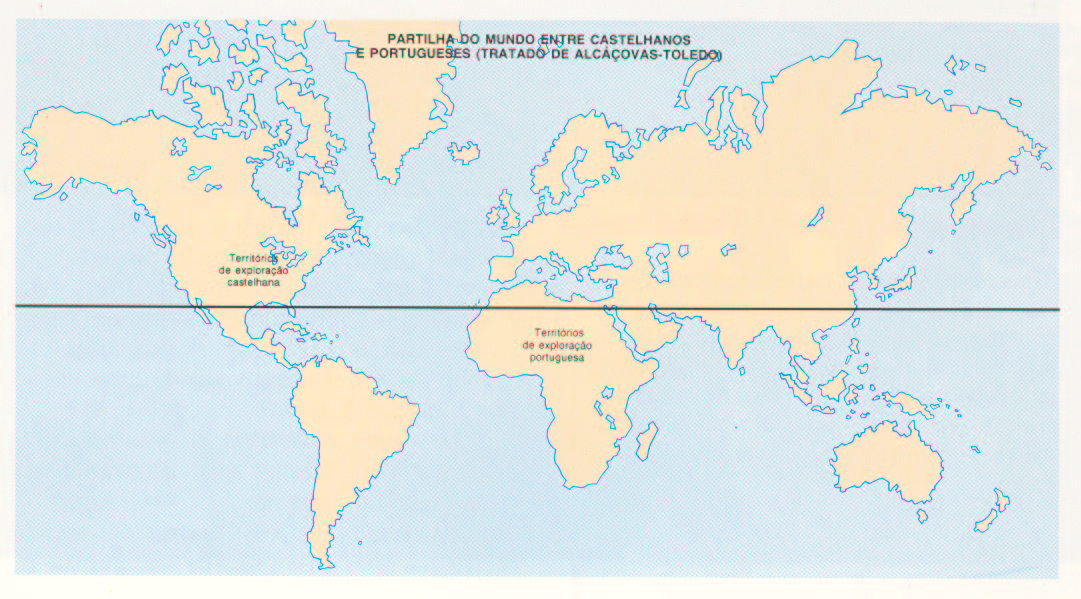

Why did Portugal accept the revision of the favorable Treaty of Alcáçovas of 1479, which granted them an exclusive right to maritime global trade and conquest south of the Tropic of Cancer (and then some), and Castille getting the rights to the north,

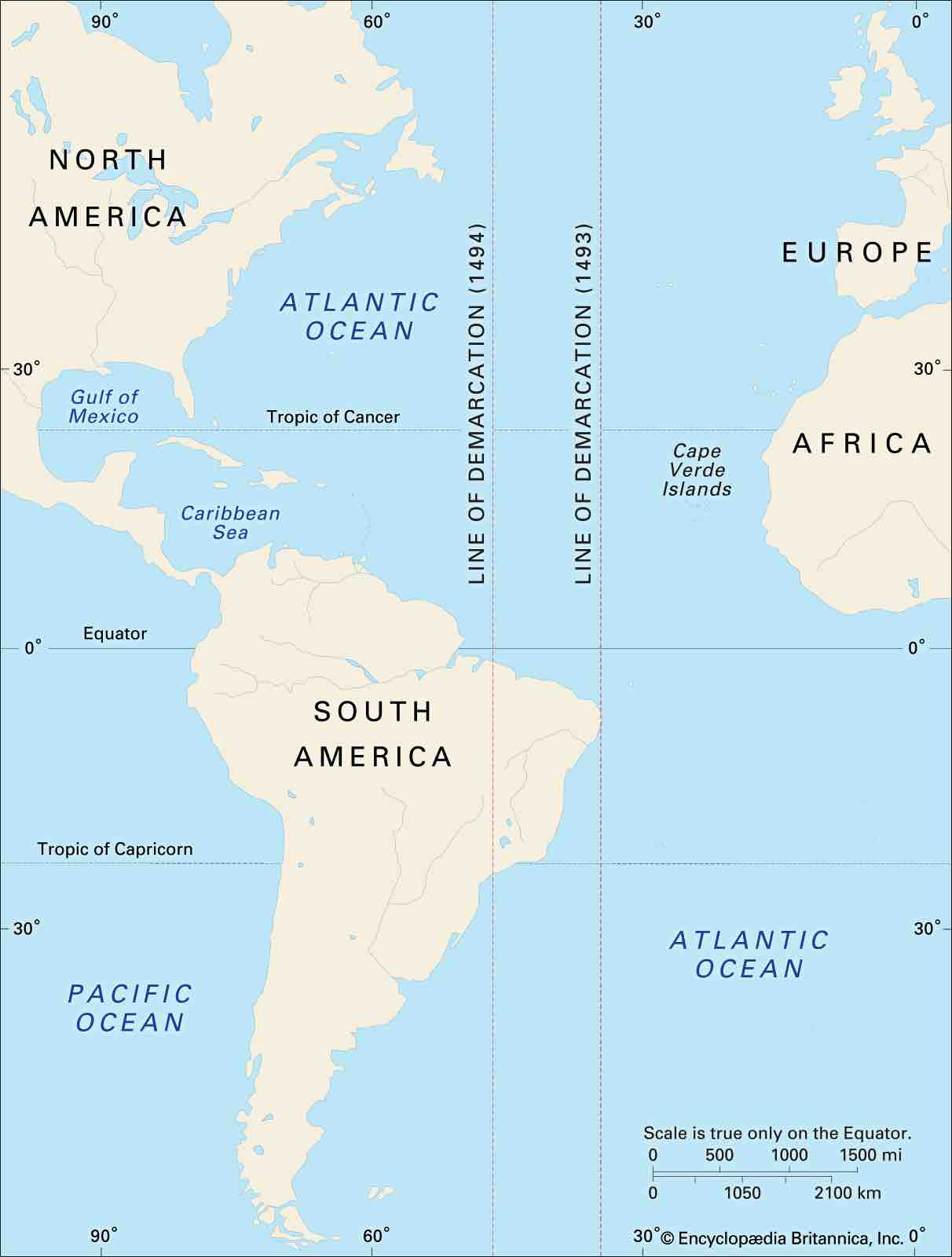

[see map above], in favor of first, the Papal Bull of Inter Caetera in 1493 which granted Portugal exclusive right to maritime global trade and conquest *east* of a line in the Atlantic, with Castille getting rights to the west, and then the slightly revised Treaty of Tordesillas, which pushed the east-west dividing line several hundred leagues further west in favor of Portugal?

[see map below]

A predictable argument in favor of changing to the Inter Caetera Line of Demarcation (1493) and Tordesillas (1494) is that the Portuguese were most invested in the eastbound route around the African Cape and already calculated this would be the shortest, most reliable way to India and the Far East based on their superior geographic calculations.

But greater faith and investment in the Cape is not a point in favor of the later treaties or a tie-breaker, it is a neutral factor between those treaties and Alcáçovas.

That is because the Cape route wasn’t just an eastbound route, it was also a southbound route, and under Alcáçovas, Portugal monopolized southbound sailing routes. So Alcáçovas, was just as good as later treaties, in that aspect.

People often like to attribute hidden, secret discoveries to the Portuguese, having them be more familiar with some of the outlines of the Americas even before the voyage of Columbus, and may propose again that they didn’t think whatever land they might have seen to the west was worth anything compared to what they knew to be in the east.

I would advise being careful with any such non-falsifiable arguments that defy Occam’s razor. Even taking them as true, they would make the decision to accept an east-west substitute for the north-south Alcáçovas, line even less logical.

Alcáçovas, as I said, already guaranteed the Cape route to Portugal, and thus Far Eastern trade in that direction. Mapping errors of the time typically misplaced Japan south of the Alcacovas line as well, and overestimated how much of China was south of it and how big Southeast Asia was. So, no urgency to change it. If Portugal also knows there is previously unknown land to the west, why concede it all to Castille, why not retain Portugal’s claim to the whole portion south of the Alcacovas line? Portugal, in Madeira and Azores, had shown just as much knowledge and enterprise in Castille in making plantations out of new Atlantic islands as Castille had in the Canaries.

So the *less* they know about land existing in the west where re-victualing or any form of development or use, no matter how minimal, the less illogical, Portuguese concessions are.

The only thing Portugal "gained" by 'flipping' from a north-south dividing line to an east-west dividing line was a monopoly on exploiting any potential *northeast* passage past Russia to the Tartary and the Far East. Under Alcáçovas, that would have have gone to Castille, under Inter Caetera and Tordesillas, it would go to Portugal.

However, I've never heard of either Iberian power thinking of exploiting the northeast passage or even setting up a Muscovy Company like Elizabethan England. Portugal and Castille were both poorly positioned to exploit any trade routes in that direction. The Kalmar Union, Muscovy, PLC, Hanseatic League, England, and Scotland, would have been far better positioned. In any case, that road always led to ice.

So the competing explanations I have for Portugal accepting the change are:

A) Wanting to secure the option of the northeast passage

B) Fear of losing or incurring costs of a confrontation with Castille that could come from vindicating claims to the southern part of the Western Hemisphere, because Columbus's journey revealed he had been there as a fait accompli.

C) Fear that Alcáçovas, was not a secure settlement that Castille would respect, anywhere in the western and eastern hemisphere, so Portugal had to try its luck with a new diplomatic settlement that would hopefully last longer

D) Fear of spiritual consequences - deference to the Pope - The Pope makes a Bull, hands down a decision, you don't refuse it

E) If you believe the Portuguese had reached North America before Columbus, fear that one of their own people would rat out their own voyages *north* of the Alcáçovas line which would have been in violation of that earlier treaty. Superseding the old treaty allows a new beginning and "no harm, no foul" about past violations.

When Columbus returned from his first Caribbean voyage, he stopped in Portuguese territory, twice, in the Azores and Lisboa, before he set foot again in Spain. He even met with the King of Portugal and bragged about his discoveries, trying to rub it in for the King not supporting him before. The Portuguese King was pissed off and was quizzing Columbus accusing him, correctly, of exploring and claiming lands too far south for Spain according to the Treaty of Alcáçovas.

The Portuguese King was pissed off, but not enough to arrest and charge Columbus for trespassing and claiming rightfully Portuguese lands in violation of the Treaty of Alcáçovas, jailing him, confiscating the Ninya, and sending out a better prepared expedition of his own in 1493. But he threatened to do it.

Between Columbus's bragging and mentions of gold, the trespassing, one could imagine the King thinking there's possibilities out west in addition to India that Portugal should follow up on, and that it would be *perfectly legal* for Portugal to claim its share of everything out west south of about 25 degrees north or the tropic of Cancer.

The King of Portugal was acting secure in his rights to Alcáçovas and fearless in his ability to enforce them.

Had he truly been fearless in the face of Spain, and the Pope, King John of Portugal would have monopolized oceanic commerce east *and* west at its early stages. The profits for Portugal would have been greater than OTL, the Indies *and* the rich part of the Americas would have fueled the Portuguese first, the Spanish would have just had to build a mega-Florida and fruitlessly search for the northwest passage. Even allowing small concessions for Spanish navigation like the tip of Florida, the Spanish would find it hard to get past geographic obstacles to the northern parts of the Far East.

Again, it would be *perfectly legal* and the Portuguese King would know about what is going on before the Spanish King and Queen do. If Portugal pressed such claims it would be the first to Cuba, the first to reach Panama, the first to trade with the Aztecs and with the Inca. The Spanish would be left with what is in Florida onward to the north.

...grande oportunidade perdida...

But alas for Portugal, King John was bluffing. What if he weren't?

[see map above], in favor of first, the Papal Bull of Inter Caetera in 1493 which granted Portugal exclusive right to maritime global trade and conquest *east* of a line in the Atlantic, with Castille getting rights to the west, and then the slightly revised Treaty of Tordesillas, which pushed the east-west dividing line several hundred leagues further west in favor of Portugal?

[see map below]

A predictable argument in favor of changing to the Inter Caetera Line of Demarcation (1493) and Tordesillas (1494) is that the Portuguese were most invested in the eastbound route around the African Cape and already calculated this would be the shortest, most reliable way to India and the Far East based on their superior geographic calculations.

But greater faith and investment in the Cape is not a point in favor of the later treaties or a tie-breaker, it is a neutral factor between those treaties and Alcáçovas.

That is because the Cape route wasn’t just an eastbound route, it was also a southbound route, and under Alcáçovas, Portugal monopolized southbound sailing routes. So Alcáçovas, was just as good as later treaties, in that aspect.

People often like to attribute hidden, secret discoveries to the Portuguese, having them be more familiar with some of the outlines of the Americas even before the voyage of Columbus, and may propose again that they didn’t think whatever land they might have seen to the west was worth anything compared to what they knew to be in the east.

I would advise being careful with any such non-falsifiable arguments that defy Occam’s razor. Even taking them as true, they would make the decision to accept an east-west substitute for the north-south Alcáçovas, line even less logical.

Alcáçovas, as I said, already guaranteed the Cape route to Portugal, and thus Far Eastern trade in that direction. Mapping errors of the time typically misplaced Japan south of the Alcacovas line as well, and overestimated how much of China was south of it and how big Southeast Asia was. So, no urgency to change it. If Portugal also knows there is previously unknown land to the west, why concede it all to Castille, why not retain Portugal’s claim to the whole portion south of the Alcacovas line? Portugal, in Madeira and Azores, had shown just as much knowledge and enterprise in Castille in making plantations out of new Atlantic islands as Castille had in the Canaries.

So the *less* they know about land existing in the west where re-victualing or any form of development or use, no matter how minimal, the less illogical, Portuguese concessions are.

The only thing Portugal "gained" by 'flipping' from a north-south dividing line to an east-west dividing line was a monopoly on exploiting any potential *northeast* passage past Russia to the Tartary and the Far East. Under Alcáçovas, that would have have gone to Castille, under Inter Caetera and Tordesillas, it would go to Portugal.

However, I've never heard of either Iberian power thinking of exploiting the northeast passage or even setting up a Muscovy Company like Elizabethan England. Portugal and Castille were both poorly positioned to exploit any trade routes in that direction. The Kalmar Union, Muscovy, PLC, Hanseatic League, England, and Scotland, would have been far better positioned. In any case, that road always led to ice.

So the competing explanations I have for Portugal accepting the change are:

A) Wanting to secure the option of the northeast passage

B) Fear of losing or incurring costs of a confrontation with Castille that could come from vindicating claims to the southern part of the Western Hemisphere, because Columbus's journey revealed he had been there as a fait accompli.

C) Fear that Alcáçovas, was not a secure settlement that Castille would respect, anywhere in the western and eastern hemisphere, so Portugal had to try its luck with a new diplomatic settlement that would hopefully last longer

D) Fear of spiritual consequences - deference to the Pope - The Pope makes a Bull, hands down a decision, you don't refuse it

E) If you believe the Portuguese had reached North America before Columbus, fear that one of their own people would rat out their own voyages *north* of the Alcáçovas line which would have been in violation of that earlier treaty. Superseding the old treaty allows a new beginning and "no harm, no foul" about past violations.

When Columbus returned from his first Caribbean voyage, he stopped in Portuguese territory, twice, in the Azores and Lisboa, before he set foot again in Spain. He even met with the King of Portugal and bragged about his discoveries, trying to rub it in for the King not supporting him before. The Portuguese King was pissed off and was quizzing Columbus accusing him, correctly, of exploring and claiming lands too far south for Spain according to the Treaty of Alcáçovas.

The Portuguese King was pissed off, but not enough to arrest and charge Columbus for trespassing and claiming rightfully Portuguese lands in violation of the Treaty of Alcáçovas, jailing him, confiscating the Ninya, and sending out a better prepared expedition of his own in 1493. But he threatened to do it.

Between Columbus's bragging and mentions of gold, the trespassing, one could imagine the King thinking there's possibilities out west in addition to India that Portugal should follow up on, and that it would be *perfectly legal* for Portugal to claim its share of everything out west south of about 25 degrees north or the tropic of Cancer.

The King of Portugal was acting secure in his rights to Alcáçovas and fearless in his ability to enforce them.

Had he truly been fearless in the face of Spain, and the Pope, King John of Portugal would have monopolized oceanic commerce east *and* west at its early stages. The profits for Portugal would have been greater than OTL, the Indies *and* the rich part of the Americas would have fueled the Portuguese first, the Spanish would have just had to build a mega-Florida and fruitlessly search for the northwest passage. Even allowing small concessions for Spanish navigation like the tip of Florida, the Spanish would find it hard to get past geographic obstacles to the northern parts of the Far East.

Again, it would be *perfectly legal* and the Portuguese King would know about what is going on before the Spanish King and Queen do. If Portugal pressed such claims it would be the first to Cuba, the first to reach Panama, the first to trade with the Aztecs and with the Inca. The Spanish would be left with what is in Florida onward to the north.

...grande oportunidade perdida...

But alas for Portugal, King John was bluffing. What if he weren't?