Mourning doveWhat's Mimia mean? My guess would be dove, peace or something similar.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Where the River Flows: The Story of Misia: A Native American Superpower

- Thread starter JSilvy

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 32 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

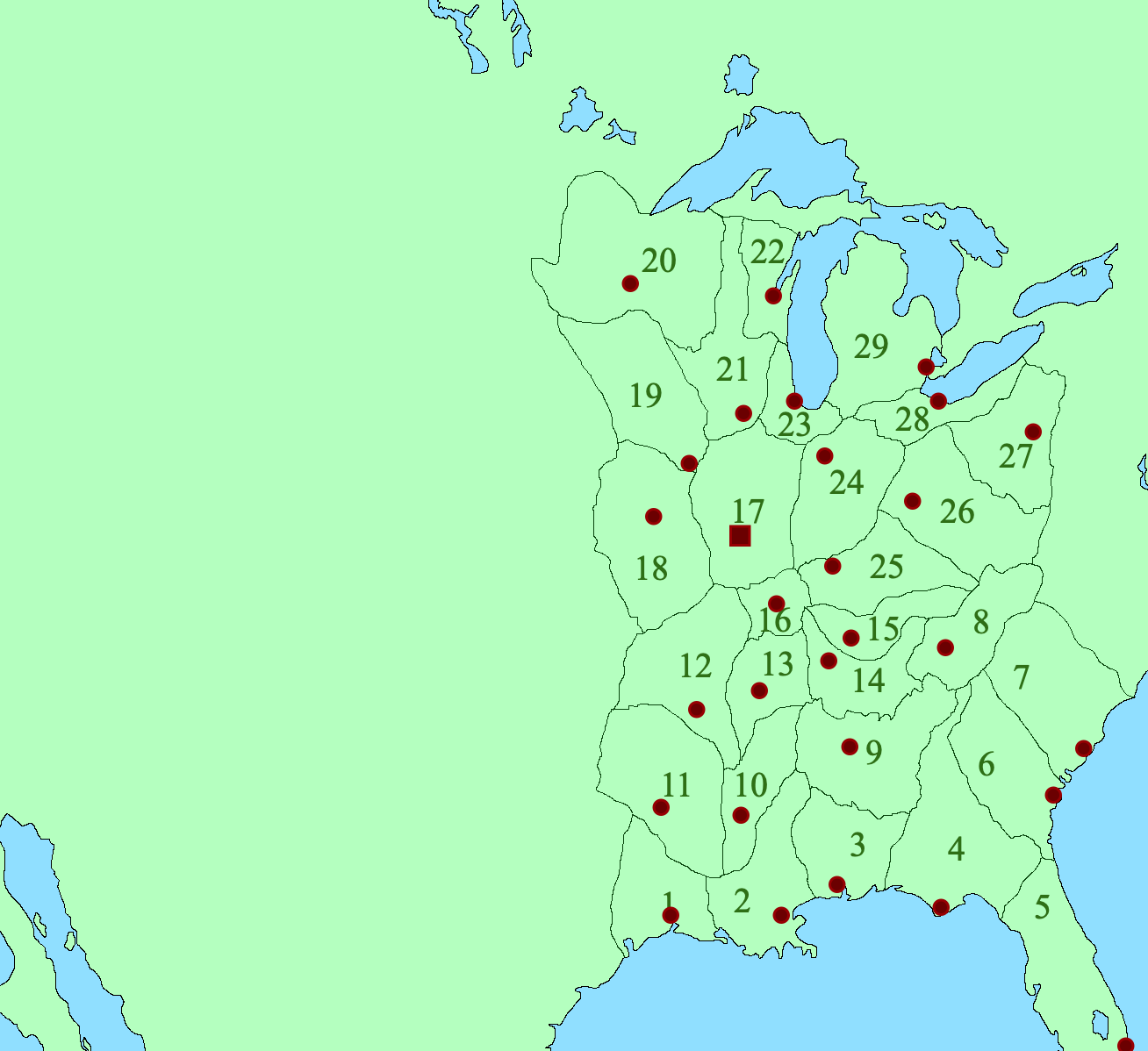

Chapter 25: The Servants of Ketzalcoatl Chapter 26: The Lynx's Den Chapter 27: The Governor Wars Chapter 28: The Maquah Constitution Chapter 29: Defenestration and Colonization Chapter 30: The Blood of the Bear Chapter 31: Mimia the Great Chapter 32: Salmon and SlavesHere's another concept for a province map. I'm currently debating several things. Some of these capitals are large coastal cities, which makes sense due to the historic importance of water transport, but I'm wondering if it makes more sense to move the capitals inland due to threat of invasion and storms. I'm also applying that question to Washtanoqua (Detroit), which is one of the largest cities on the Great Lakes but is right on the border with Haudenosaunee territory. Alternatively, I'm wondering about splitting Patowa (Michigan mitten peninsula) into two provinces, with a smaller eastern province around Washtanoqua and the thumb and a larger western province with the rest. As for Pikate (peninsular Florida), I currently have Tekesta (Miami) as the capital, but I'm considering moving it to Tanpa (Tampa) due to it being more sheltered from Spanish in the Bahamas and Cuba. Thoughts?

Misian Provinces- capitals

1- Atakapa- Nakasila

2- Ahkowe- Shawasha

3- Chatwah- Mabila

4- Apalacha- Apalachiqua

5- Pikate- Tekesta

6- Maskokia- Yamacraw

7- Catapwa- Kiawah

8- Aniwiya- Satapo

9- Alapama- Tashaka

10- Tunica- Talula

11- Catowa- Nashitusha

12- Akansa- Kikatam

13- Nalumen- Tipiwik

14- Kakinam- Naniapa

15- Wasiotwah- Minowasi

16- Sakiwe-Nicota

17- Inoka- Cahoqua

18- Wimisorita- Nipafsaqua

19- Pakoshe- Kikoqua

20- Machikato- Pateota

21- Kikapowa- Sinesipa

22- Winepa- Ashwapenon

23- Michikamia- Shicaqua

24- Miyamia- Wiatenon

25- Shawanokia- Chinquia

26- Washashe- Minutaliw

27- Awansahseni- Minohiyo

28- Irirona- Santusti

29- Patowa- Washtanoqua

Misian Provinces- capitals

1- Atakapa- Nakasila

2- Ahkowe- Shawasha

3- Chatwah- Mabila

4- Apalacha- Apalachiqua

5- Pikate- Tekesta

6- Maskokia- Yamacraw

7- Catapwa- Kiawah

8- Aniwiya- Satapo

9- Alapama- Tashaka

10- Tunica- Talula

11- Catowa- Nashitusha

12- Akansa- Kikatam

13- Nalumen- Tipiwik

14- Kakinam- Naniapa

15- Wasiotwah- Minowasi

16- Sakiwe-Nicota

17- Inoka- Cahoqua

18- Wimisorita- Nipafsaqua

19- Pakoshe- Kikoqua

20- Machikato- Pateota

21- Kikapowa- Sinesipa

22- Winepa- Ashwapenon

23- Michikamia- Shicaqua

24- Miyamia- Wiatenon

25- Shawanokia- Chinquia

26- Washashe- Minutaliw

27- Awansahseni- Minohiyo

28- Irirona- Santusti

29- Patowa- Washtanoqua

I'll give my thoughts, since the American riverine system is an obvious interest of mine:

1) Keep: Shawasha especially, but also Maubila, are way, WAY too big and useful ports and populated metropolises to ignore their importance now and in the future. Everything, everything will gravitate to them anyway and so you may as well concentrate political with the economic capital there.

2) Maybe: Charleston and Savannah COULD move inland not because of hurricanes or defense - they're great ports, obviously, and sheltered ones - but their OTL states were fertile and flat enough to allow a population both spread-out AND densely concentrated, and so Columbia and Milledgeville-then-Atlanta became the capitals as more central locations for all to travel to in an equidistant manner. If population density works out like OTL, it could be useful for them to change. Washtanoqua can be argued like Shawasha - it's such an important port and lake chokepoint it may be best to see everything political and military concentrated there for maximum alertness. I could also see the wisdom in having the top chunk of Michigan's Lower Peninsula combine with the Upper, and a capital at Makina/*Mackinac Island for the same reason.

3) Change: Apalachiqua is hurricane-prone like the other coastal sites mentioned, but it isn't even a big or sheltered port like the rest (if I remember right), whilst having flat, fertile land like Maskokia and Catapwa's for farmers to spread out on. I would recommend Coweta Falls/*Columbus, GA as a central capital site and it's the navigable head for the Chattahoochee which flows into the Apalachicola. Tanpa for Pitake also makes sense - it's more central, still easily sailed to, and Tekesta will ALWAYS be a major civilian and naval port for Misia no matter a lack of capital status due to being both a key waypoint/chokepoint in-and-out of the Gulf of Mexico and the obvious immigrant port outside of Shawasha, so it'll be well-linked to and controlled anyway.

This table of American rivers' navigability (starting at page 146) should be of use. I also would say that Misia could perhaps create a TTL version of the Atlantic and Great Western Canal (I've seen its southern-linked river variously be the Altamaha or Savannah) be created to compete with the Iroquois's *Erie Canal someday, and that would turn *Atlanta's site into a major metropolis for Apalacha, even more so if they decide to make a secondary connection to the Chattahoochee.

1) Keep: Shawasha especially, but also Maubila, are way, WAY too big and useful ports and populated metropolises to ignore their importance now and in the future. Everything, everything will gravitate to them anyway and so you may as well concentrate political with the economic capital there.

2) Maybe: Charleston and Savannah COULD move inland not because of hurricanes or defense - they're great ports, obviously, and sheltered ones - but their OTL states were fertile and flat enough to allow a population both spread-out AND densely concentrated, and so Columbia and Milledgeville-then-Atlanta became the capitals as more central locations for all to travel to in an equidistant manner. If population density works out like OTL, it could be useful for them to change. Washtanoqua can be argued like Shawasha - it's such an important port and lake chokepoint it may be best to see everything political and military concentrated there for maximum alertness. I could also see the wisdom in having the top chunk of Michigan's Lower Peninsula combine with the Upper, and a capital at Makina/*Mackinac Island for the same reason.

3) Change: Apalachiqua is hurricane-prone like the other coastal sites mentioned, but it isn't even a big or sheltered port like the rest (if I remember right), whilst having flat, fertile land like Maskokia and Catapwa's for farmers to spread out on. I would recommend Coweta Falls/*Columbus, GA as a central capital site and it's the navigable head for the Chattahoochee which flows into the Apalachicola. Tanpa for Pitake also makes sense - it's more central, still easily sailed to, and Tekesta will ALWAYS be a major civilian and naval port for Misia no matter a lack of capital status due to being both a key waypoint/chokepoint in-and-out of the Gulf of Mexico and the obvious immigrant port outside of Shawasha, so it'll be well-linked to and controlled anyway.

This table of American rivers' navigability (starting at page 146) should be of use. I also would say that Misia could perhaps create a TTL version of the Atlantic and Great Western Canal (I've seen its southern-linked river variously be the Altamaha or Savannah) be created to compete with the Iroquois's *Erie Canal someday, and that would turn *Atlanta's site into a major metropolis for Apalacha, even more so if they decide to make a secondary connection to the Chattahoochee.

Last edited:

I wonder what has happened to South East Asia considering that the Villalobos and Legazpi expeditions must have been butterflied away. It would have given Portugal uncontested supremacy in every water east of Cape of Good Hope, as it's not likely that Spain will be anything more than an Atlantic power.

However, Spain can be more powerful at that: the smaller scale of Castillian depopulation will also help the Peninsula preserve its economic power.

Also, Mexico can start projecting power into the Pacific especially considering the French expeditions on their northwestern flanks (which, I assume, used Mexican ships and industry).

However, Spain can be more powerful at that: the smaller scale of Castillian depopulation will also help the Peninsula preserve its economic power.

Also, Mexico can start projecting power into the Pacific especially considering the French expeditions on their northwestern flanks (which, I assume, used Mexican ships and industry).

Last edited:

Unfortunately, I tested positive for COVID early this afternoon.

Fortunately, that means I actually have time to myself for once.

Unfortunately, I'm not focused enough to write.

Fortunately, I am focused enough to make more maps.

This is a French map showing the Cochiman Peninsula and surrounding areas just prior to their arrival, including the major Pericu cities of Airapi and Yenecami, the oases of Kadakaaman (Cadacamme) and Kaaman Kagaleha (Cagalais), and the wealthy salt-mining city of Awaa Cala (Aoua Calas). Visible are the empires of the Meshica and the Dinei as well as the young and soon to be short-lived Mulagi Kingdom. The major tribes and ethnic groups of the peninsula are also shown, including the dominant Cochimi, the also mostly nomadic Monki and Waikuri, and the settled and maritime Pericus of the southern tip. It is worth noting that the borders of these states largely pass through wastelands, so the borders are not entirely precise.

Fortunately, that means I actually have time to myself for once.

Unfortunately, I'm not focused enough to write.

Fortunately, I am focused enough to make more maps.

This is a French map showing the Cochiman Peninsula and surrounding areas just prior to their arrival, including the major Pericu cities of Airapi and Yenecami, the oases of Kadakaaman (Cadacamme) and Kaaman Kagaleha (Cagalais), and the wealthy salt-mining city of Awaa Cala (Aoua Calas). Visible are the empires of the Meshica and the Dinei as well as the young and soon to be short-lived Mulagi Kingdom. The major tribes and ethnic groups of the peninsula are also shown, including the dominant Cochimi, the also mostly nomadic Monki and Waikuri, and the settled and maritime Pericus of the southern tip. It is worth noting that the borders of these states largely pass through wastelands, so the borders are not entirely precise.

Last edited:

Hoping for a quick recovery. Best wishes.Unfortunately, I tested positive for COVID early this afternoon.

Hope you get well man, I tested positive once, and my throat gave me hell.Unfortunately, I tested positive for COVID early this afternoon.

Fortunately, that means I actually have time to myself for once.

Unfortunately, I'm not focused enough to write.

Fortunately, I am focused enough to make more maps.

Thanks!Hoping for a quick recovery. Best wishes.

Yeah, my throat's been kinda meh but I assumed I was blowing it because I had to go to tech week every night for a show I was producing. I got tested yesterday and immediately went into quarantine. My throat is generally pretty sore, but I just drank some tea with honey that immediately killed the soreness for the time being.Hope you get well man, I tested positive once, and my throat gave me hell.

I should be. I'm fully vaxxed and boosted. I have one dose of J&J and two of Pfizer. While I have a sore throat and a clogged (sometimes runny nose), it basically feels like having a shitty cold. Given that I'm in my 20s and well protected I'm not too worried. Also my quarantine is expected to end before the time I planned to go to visit my parents next week, which is really my main concern at this point.Hope you'll be okay dude

If you're not fully recovered by then, mum's cooking should be able to heal any last ailmentsThanks!

Yeah, my throat's been kinda meh but I assumed I was blowing it because I had to go to tech week every night for a show I was producing. I got tested yesterday and immediately went into quarantine. My throat is generally pretty sore, but I just drank some tea with honey that immediately killed the soreness for the time being.

I should be. I'm fully vaxxed and boosted. I have one dose of J&J and two of Pfizer. While I have a sore throat and a clogged (sometimes runny nose), it basically feels like having a shitty cold. Given that I'm in my 20s and well protected I'm not too worried. Also my quarantine is expected to end before the time I planned to go to visit my parents next week, which is really my main concern at this point.

Chapter 25: The Servants of Ketzalcoatl

Chapter 25: The Servants of Ketzalcoatl

Itzcoatl walked through the main market located in the Pericu quarter of Matanchen, not far from the shore. On his otherwise bare shoulders he wore a jaguar-fur shawl and carried a ceremonial jade-tipped brass spear. Walking behind each of his shoulders were three more men, six in total, each carrying an imperial-produced musket with a polished bayonet fixed onto the end. Perhaps it was not the most direct route, but the cotton tarps that stretched across the narrow streets guarded him from the sun that beat down much hotter than up in the highlands of Tenochtitlan. On his way he nearly tripped over several children who were running about, punting a rubber ulama ball with their forearms, almost falling into two piles of salt and a red dust that was presumably some sort of ground pepper.

Although the indigenous Nayari people made up the majority population of the city, Pericu trade was its lifeblood, and the Pericu quarter was its beating heart. Matanchen was perhaps one of the oldest continuously inhabited sites in Mesoamerica going back millennia, but until well under a thousand years ago, it was one of the many small and unimportant fishing villages dotting the hair’s-width coastal strip between the central highlands and the vast Pacific that never supported the same type of great maritime commerce and culture that existed in the east. When the Pericu arrived, they brought salt from Awaa Cala, glass from Kutsan, pottery from Ashipewahk, minerals and lumber from Dadacia, wool from Cochiman herders, and the elusive Pericu pepper in exchange for Mesoamerican cotton, gold, cacao, spices, honey, and octli and balche. In the span of a few decades, the town transformed from a sleepy village into a thriving port, connecting the Nayaris to West America. In Tenochtitlan, the Pericu, referred to as the “Pelicatecs”, came to be known as the “The Taino of the West”– a bizarre group of outsiders with alien customs who nonetheless played a vital economic role as seafaring merchants.

At the other end of the market, he reached a large, stone building with several chimneys with vents on top. As he approached the large arched doorway, he glanced at a sign written in the Pericu script on top and Meshica script underneath. As he read the words “Yenecami Inn”, he knew he was at the right place. He held his arm down and behind him, palm facing back towards the men behind him, ordering them to stop. He reached his arm behind his right shoulder, and with a come hither motion he ordered the first musketeer behind his right shoulder to enter with him.

The building was significantly cooler on the inside than it was outside. There were a number of tables around which men were gathered, drinking a variety of beverages of a variety of colors out of glass cups. Around one table, a large number of men were gathered, cheering over some game which Itzcoatl could only determine if he could see over the heads of the large crowd. To the right, he saw a long stone counter, on top of which a middle aged Pericu man with three colorful feathers sticking out of his head bun was pouring drinks out of glass bottles which he kept on the shelf behind him. Itzcoatl approached the counter and struck it with his staff to get the man’s attention. The Pericu man, who was busy wiping off a bottle with a piece of cloth, glanced over, finished what he was doing, and placed the bottle back on the shelf before making his way over.

“Can I help you?”

“I’m not from around these parts. You tell me what you recommend.”

“Well,” he said, “if you’re from elsewhere in the empire I’d assume you’re used to octli and balche, but of course we also import some drinks from abroad.”

“Like Kutsan wine?”

“So you’re familiar with what Matanchen has to offer.”

“Of course, but I would also love to be familiar with the person serving me.”

“The name’s Yenec.”

“Yenec, that’s a peculiar name.”

“Well, my parents named me for the city our ancestors came from, Yenecami. The inn’s named after the place too. My ancestors who built this place figured the name would be a comfort to fellow travelers from the peninsula.”

“You ever been there?”

“Of course! In my younger days I ran with some sailors up and down the Sea of Aztlan. I’d pass by Yenecami all the time on the way north.”

“You’ve been to Kutsan?”

“Yes, I’ve even been all the way up to Orayvi and prayed to Maasaw Tuparan in the Great Kiva.”

Itzcoatl did not know much about the Pericu religious practices, but he could tell the smiling innkeeper was happy to be asked about his travels.

“I’ve never been in a Kiwa.”

“They’re lovely. Temples with great underground chambers where you can really commune with the creator and his son.”

“This sounds an awful lot like what those Kwistecs believe.”

“No sir, of course not,” he responded. “Those who follow Maasaw Tuparan are loyal to Tenochtitlan. We would never kill countless of our human brothers like the Salvation Army. But anyway, I could also tell you about my travels to Awaa Cala. Beautiful white sands and salt formations. All of the salt in the world comes from there, and that’s not even to mention the whales that come every year. They have an absolutely beautiful kiva there as well. Where are you from, may I ask?”

“Tenochtitlan.”

Yenec looked at the jade spear and noticed the man behind Itzcoatl holding a musket.

“Huh, we don’t get very many imperial agents in these parts. What brings you here?”

“Local tax records show that the price and quantity of sales of Kutsan wine have gone up dramatically. It seems that a lot of the sales have been coming from your establishment.”

“Well who doesn’t love wine? If you would like to try some we have plenty now that the latest shipment came in.”

“Has anyone here bought your wine in bulk?”

“A few people actually.”

“Do you have any names?”

“Well, there is one person. Cheyuwac, the priest. He runs the central Kiva.”

“Oh, is there an upcoming Pericu religious festival involving grape wine?”

“No, not particularly, at least not in the lands of the Pericu. I mean, we like it, but we mostly use nochtli wine for our religious rituals.”

Itzcoatl paused to contemplate. Seeing the look on his face, Yenec continued.

“I know, typically most of you locals associate the Pericu with Kutsan grape wine. Truth is we never really grew grapes in the land of the Pericu. That mostly comes from parts of Kutsan and Dadacia. I guess you don’t really associate us with nochtli so much since you lot already have that here.”

“I guess my question is,” said Itzcoatl–

“Hey Yenec!” a man shouted in a think Pericu accent, stumbling towards the bar and slamming down a coin. “Pour me some more of that Octli?”

“Of course,” said Yenec, pouring the bottle into a small glass. Itzcoatl looked on as the man who had just unintentionally shouted in his ear lifted the shot and gulped it down in a matter of seconds. He left another coin as if he had forgotten to pay and walked away.

“Sir, you forgot your– eh, forget it.”

Yenec turned back towards Itzcoatl.

“Sorry. As you were saying?”

“My question is, why do you think this priest of your Pericu religion is purchasing wine in bulk if you have no such ritual involving it? Do you think he’s having a big wine party?”

“No sir, that doesn’t sound like the Cheyuwac I know. Perhaps he’s buying it for someone else.”

Itzcoatl’s stare tightened. Considering it a confused expression, Yenec elaborated.

“Tuparan tells us to help and cooperate peacefully with others, so maybe he’s just being helpful. Maybe there are just a lot more people in the city who just drink a lot more wine for some reason and he’s doing them a favor.”

“So let’s say there was another group of people in the city that used wine for ritual purposes.”

“Well, I’m not sure who that would be, but I’m sure that Cheyuwac would be perfectly willing to–”

Yenec noticed that Itzcoatl’s eyebrows raised and his eyes widened as he turned to look at the musketeer behind his shoulder. He decided he had said too much.

“You know what?” Itzcoatl said. “That’s enough. Thank you. Please, if you could just let us know where we could find him?”

“Well sir, he’s a priest of Maasaw. You can usually find him by the town Kiwa.”

***

It was not a particularly large mass, but it was good enough. They may not have had their own building, but the dense forests outside of Matanchen were tranquil and provided shelter from the threat of imperial agents. The fact that Petlo was able to help so many flee west after the failed rebellion was a miracle. The fact that Petlo was able to build a congregation of dozens in this strange new place was also a miracle. The fact that Petlo and his comrades were able to convert local Nayaris and convince them to join the congregation was a miracle even more so.

One of the greatest miracles of all, however, had been the hospitality of the locals. Most people out east had never met a Pericu or any other Maasawist for that matter, but they instantly found a connection with these peace-loving individuals who, although were of a different faith, shared similar values. Petlo had found comradery in the local Maasawist priest, and he knew that his friend would be there any second as per usual to deliver the communion wine.

All of a sudden, from the woods behind every tree emerged men with metal chest plates and muskets fixed with bayonets who began to charge towards the congregation. Several dozen men were now crowded together in the narrow opening of the forest that was once their sanctuary. In front of them all stepped a man with bare shoulders who wore a jaguar-fur shawl and carried a ceremonial jade-tipped brass spear.

“In the name of the Emperor Montezuma VI and of the gods whom he serves, the Servants of Ketzacoatl place you under arrest.”

Petlo looked at the leader of the musketeers. Over his shoulder, he saw a man in white linen with a blue satin head wrap held in place by a leather band with a red feather sticking out.

“Cheyuwac!” Petlo said. “We trusted you! What is the meaning of this!”

Musketeer to Itzcoatl’s right raised his weapon towards the Christian priest but Itzcoatl held his hand out to the sound telling him to stand back.

“Don’t kill him. The emperor says that as many as possible are to be captured alive for sacrifice. Now take them away!” he ordered. “Tie them up and throw them into the wagons!”

As the men marched off with the captured Christians, Itzcoatl and Cheyuwac stayed behind.

“I did what you asked. Is our agreement kept?”

“Yes,” Itzcoatl said. “You and your people are not to face any harm. However, if we catch you aiding the Kwistecs any further, the Pericu will be sacrificed alongside them. Is that clear.”

“Of course,” said the priest.

“Good. Glad we have arrived at an understanding.”

Itzcoatl followed his men and the Christian prisoners. Cheyuwac remained in silence.

Horrible that Cheyuwac sold out the Christians but I understand why he did it.

Yeah, if it's you and your own community vs another smaller community, it's not a great situation, but the right choice to take is clear.Horrible that Cheyuwac sold out the Christians but I understand why he did it.

So life update: I'm graduating from university in about a month and for the next few weeks any non-academic writing I do will be purely in the form of procrastination. I don't quite have the focus to go back to the Maquah the Mad arc yet, but I have been jumping around in the timeline writing some easier things in the meantime.

If anyone wants a teaser, of what I've been writing I'll put one here. This is two paragraphs from the end of a chapter I just wrote. It doesn't explicitly spoil anything I am writing about right now, but is a spoiler for what future plot lines I plan to introduce. In the meantime this can also be feedback if this is something you guys want to see.

If anyone wants a teaser, of what I've been writing I'll put one here. This is two paragraphs from the end of a chapter I just wrote. It doesn't explicitly spoil anything I am writing about right now, but is a spoiler for what future plot lines I plan to introduce. In the meantime this can also be feedback if this is something you guys want to see.

That is, until a Taino man by the name of Akwey Tuho in 1729 published the controversial pamphlet A Call for Integration. Tuho was himself a scholar and philosopher with a number of Jewish friends, and considered himself to be influenced by the work of Baruch Spinoza. In the pamphlet, Akwey argued that Zemism and Taino identity were no longer relevant in the modern world. He argued that the days of Taino civilization were far in the past and would never return, and therefore they would be best simply assimilating into the societies in which they lived. In his essay, he referenced Spinoza, and argued that if they did not assimilate they would simply end up like the Jews, “a race in exile for near eight times as long as we, who have for centuries endured a pointless persecution and wailed for a return to their ancient land that has never and shall never come to them”. Immediately, Lafi Pentafit read the work and was thrown into a rage. In a single day, he wrote an 18-page lambastment of Tuho’s work titled A Call Against Ignorant Drivel, calling him a “spineless wreck with not an ounce of dignity or care for the fate of his race nor my own”, and ending with a call “for all children of Israel wherever they may be […] to prove this imbecile’s falsehoods to be pure idiocy, to arise to the call of self-deliverance, and to once and for all reclaim the lands of their ancestors”.

Immediately, the work sent shockwaves throughout Shawasha and the intellectual circles of other coastal cities. Lafi lost a large number of his friends for his crassness, being described as a "feces-covered cretin", but a surprising number of individuals, particularly fellow anti-assimilationist Jews and Tainos agreed with him, even receiving a thank you letter from the city's most prominent Zemist priest, which he had printed copies of and taped to the door of Tuho's home while having the original framed. Back in Manhattan, a number of Jewish intellectuals in the community he had left behind picked up the work to mock him, but even many of them began to support his message. What started out as a bunch of petty ramblings against a fellow philosopher ended up becoming the birth of the Erezist movement, a movement that would have world-changing effects. Although he was a short man whose head was already balding, Lavi ben David would be the man responsible for Jewish liberation, and he would do so through sheer spite alone. His unbridled enthusiasm could not be curbed.

Immediately, the work sent shockwaves throughout Shawasha and the intellectual circles of other coastal cities. Lafi lost a large number of his friends for his crassness, being described as a "feces-covered cretin", but a surprising number of individuals, particularly fellow anti-assimilationist Jews and Tainos agreed with him, even receiving a thank you letter from the city's most prominent Zemist priest, which he had printed copies of and taped to the door of Tuho's home while having the original framed. Back in Manhattan, a number of Jewish intellectuals in the community he had left behind picked up the work to mock him, but even many of them began to support his message. What started out as a bunch of petty ramblings against a fellow philosopher ended up becoming the birth of the Erezist movement, a movement that would have world-changing effects. Although he was a short man whose head was already balding, Lavi ben David would be the man responsible for Jewish liberation, and he would do so through sheer spite alone. His unbridled enthusiasm could not be curbed.

Sounds kinda based tbhI am still thinking about Jewish/Taino pirate republics.

can you create Neu Jerusalem with tgat giant temple

Also, will they (the Erezist Jews) also be infected with North American capitalism?

According to Jewish law, there can't be a Third Temple anywhere but exactly where it stood before.

Threadmarks

View all 32 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 25: The Servants of Ketzalcoatl Chapter 26: The Lynx's Den Chapter 27: The Governor Wars Chapter 28: The Maquah Constitution Chapter 29: Defenestration and Colonization Chapter 30: The Blood of the Bear Chapter 31: Mimia the Great Chapter 32: Salmon and Slaves

Share: