You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Where the River Flows: The Story of Misia: A Native American Superpower

- Thread starter JSilvy

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 32 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

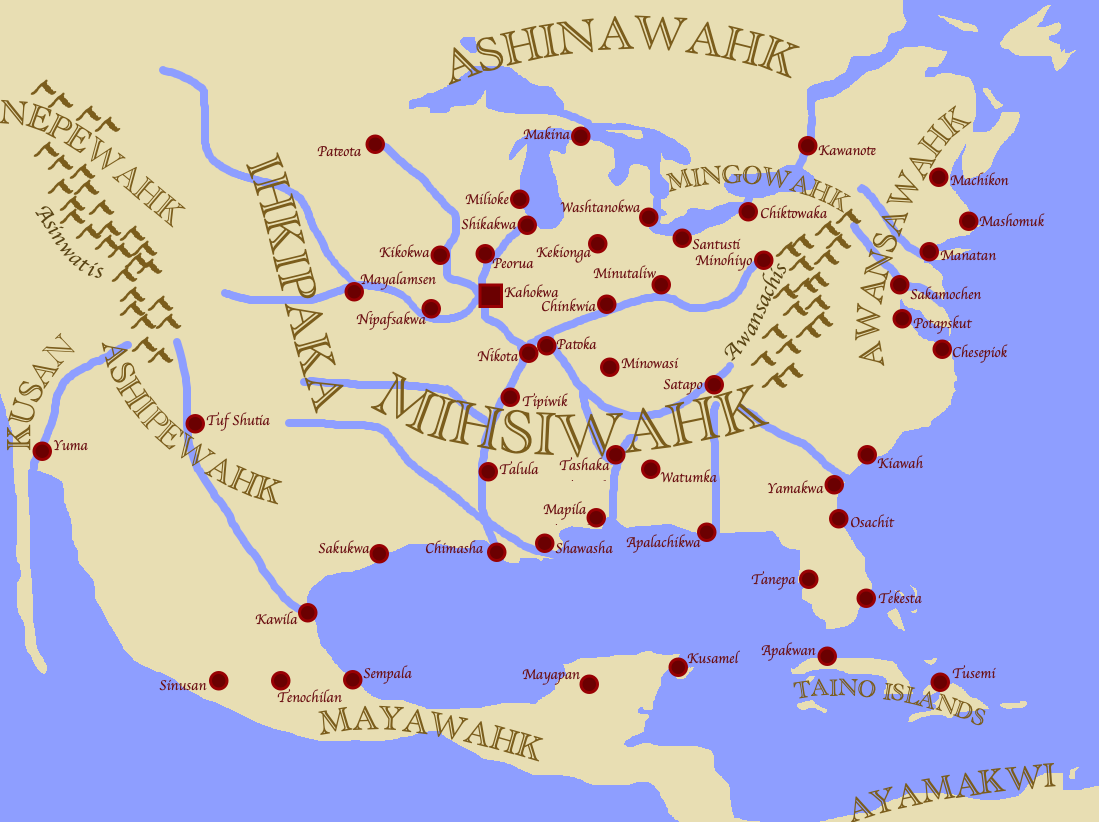

Chapter 25: The Servants of Ketzalcoatl Chapter 26: The Lynx's Den Chapter 27: The Governor Wars Chapter 28: The Maquah Constitution Chapter 29: Defenestration and Colonization Chapter 30: The Blood of the Bear Chapter 31: Mimia the Great Chapter 32: Salmon and SlavesUpdate: a fixed version of the Medieval Map including more rivers and cities.

Mihsiwahk– The Great Kingdom

Ashinawahk– Land of the Ashinabe/Ojibwe

Mingowahk– Land of the Mingwes (Iroquoians)

Awansawahk– The Eastern Land

Ihkipaka– The Grasslands

Nepewahk– The Dead Land

Ashipewahk– The Land of Cliffs

Kusan– Kutsaan (comes from local name of civilization)

Mayawahk– The Southern Land (initially a false cognate with "Maya", although overtime the term has become associated with them)

Ayamakwi– The Far South

Asinwatis– Rockies (comes from local native name)

Awansachis– Appalachians / Eastern Mountains

Thoughts?

Mihsiwahk– The Great Kingdom

Ashinawahk– Land of the Ashinabe/Ojibwe

Mingowahk– Land of the Mingwes (Iroquoians)

Awansawahk– The Eastern Land

Ihkipaka– The Grasslands

Nepewahk– The Dead Land

Ashipewahk– The Land of Cliffs

Kusan– Kutsaan (comes from local name of civilization)

Mayawahk– The Southern Land (initially a false cognate with "Maya", although overtime the term has become associated with them)

Ayamakwi– The Far South

Asinwatis– Rockies (comes from local native name)

Awansachis– Appalachians / Eastern Mountains

Thoughts?

Last edited:

Chapter 9: A Fortress Breached

(missed me? I know this isn't the longest or most detailed chapter, but I wanted to be able to write something on Misia)

Can any city in the Christian realm compare to the glory of Xahuaxa? A port such as this puts even nearby Mabila to shame. In every direction are great golden buildings of limestone surrounded by bronze clay houses on the outskirts, alas they have all been stained with ash. Within the great walls of the Golden City lie grand palaces and temples to their pagan god, which could be easily converted into a cathedral unlike any existing house of Christendom. Oh, what great canals bring men and riches across its face! Oh, what treasures are to be found in its markets! Oh, what fertile lands surround it to bless it with its bountiful harvests?

– journals of Hernan Cortes following the Battle of Shawasha

Chapter 9: A Fortress Breached

Can any city in the Christian realm compare to the glory of Xahuaxa? A port such as this puts even nearby Mabila to shame. In every direction are great golden buildings of limestone surrounded by bronze clay houses on the outskirts, alas they have all been stained with ash. Within the great walls of the Golden City lie grand palaces and temples to their pagan god, which could be easily converted into a cathedral unlike any existing house of Christendom. Oh, what great canals bring men and riches across its face! Oh, what treasures are to be found in its markets! Oh, what fertile lands surround it to bless it with its bountiful harvests?

– journals of Hernan Cortes following the Battle of Shawasha

The mouth of the Mississippi River has shifted throughout its history, changing its course. In some previous eras, the river would empty along the course of what is today known as the Atchafalaya River. During these eras, the city of Chimasha would reign dominant on the southern coast of Misia. In some eras, the river would instead shift east, taking its normal course, which would eventually become the standard course of the river through the careful management of the Misians. It would be this eastward shift that would allow a once modest village to grow into the great city of Shawasha.

At the time Columbus first arrived in the New World, Shawasha was one of the largest cities in the empire, second only to Cahoqua. According to imperial censuses at the time, the city was home to around 300,000 people. Its location where the river system that held together tens of millions of people met the busy and vibrant South Misian Sea made the city wealthy as a key center of trade. Although most of the population was Hileni Misian, there were large communities of Tainos, Mayans, and Nawas, some even living in the inner portions of the city (although most tended to live in the outer portions closer to the docks). There are records of Misian bureaucrats in southern Shawasha who would go to the minority neighborhoods to try the foreign cuisine and drink balche. One record even tells of a young Misian scholar who was kicked out of a Mayan tavern for mocking Mayan culture and asking for human flesh, in reference to the admittedly accurate stereotype of Mayans practicing human sacrifice. In reality, many local ethnic Mayans had adopted the Midewin religion. Still, Taino and Mesoamerican temples existed alongside those of the Midewin faith.

Like other cities in the New World, Misia was hit hard by the plague, especially given its enormous population and its status as a center of New World trade. While the population may have been brought down to as little as 50,000, the massive amount of available food and resources made city dwelling even easier and encouraged further trade. From both migration and high birth rates, the population of Misia rebounded to more than twice that amount. Some of the outermost districts beyond the walls made up of bronze colored buildings constructed out of bricks and baked clay from the river were still rather empty. Numerous inhabitants were able to move further into the inner city, with many of those now living outside of the inner walls being newer arrivals, minorities, and merchants. These merchants would often bring in goods from the nearby piers and bring them along the streets or canals to be sold in the central market.

On 7 August 1522, Cortes would begin his attack on this city on the soft underbelly of the Great Kingdom. By this point, many Misian troops had been diverted to Mabila and the border of Spanish territory on the Pikate peninsula, both of which had seen significant skirmishes. While the local generals believed that the existing garrison was enough to defend the city, they were not fully prepared for the Spanish invasion, which was even larger than the force attacking Mabila.

One defensive advantage that Shawasha held over Mabila was that while Mabila was effectively on an open bay, Shawasha was a bit up river. While it had some points that were accessible to harbors and lakes which connected to the ocean, these points were defensible. Attacking the city by land also entailed marching through difficult swampland– land in which the Misians were accustomed to maneuvering. Of course, bringing boats up the river would also leave them quite vulnerable to attack, although the river was wide enough that keeping boats in the middle of the river would give them protection from attacks on the mainland as they made their way up.

The Spanish strategy was therefore to send ships up the mouth of the Mississippi alongside several canoes. On the swampy land, Calusa soldiers and Misian defectors, mostly from Mabila and the surrounding area, would run up the course of the river attacking any Misian forces defending its run. Meanwhile, to divide the Misian defense, another group of boats would use their naval superiority to break through the straits to access Lake Chepuna to the north of the city. The Spanish would land on the shores and march through the marshy land toward the city to the south, but the local Misian forces would be able to push back the Spanish, who were unable to use many of their firearms due to the humid conditions and who were unable to make full use of their cavalry.

From the middle of the river, Spanish ships fired their canons upon the city, destroying as many structures as they could. On August 11, after the first failed land invasion of the city, Spanish troops on Lake Chepuna made another even larger landing to draw as many Misian forces as possible to the north, while another landing was made in the city from the south on the riverbank just east of the city. This time, the Spanish were able to surround Shawasha and continue to bombard its walls. The Spanish marched through the outer-portions of the city, slaughtering anyone who resisted. Using the narrow alleyways, Misian forces attempted to attack the encroaching Spanish. Cortes simply told his troops to fire back and keep marching along the main thoroughfares towards the inner walls.

Upon reaching the inner wall, the Spanish issued an ultimatum– either all of the inhabitants would surrender and convert to Christianity or everyone would be killed. Seeing how quickly the Spanish breached the city, Shawasha surrendered. Cortes then declared everyone would be baptised, and every household would have to volunteer at least one man to serve alongside the Spanish.

On the 15th, a Misian force arrived from upriver. They surrounded the city expecting to siege it and starve out the Spanish. Misian riverboats had some success boarding and sinking Spanish ships, but upon landing, the Misians were surprised to see a large force consisting of Misian soldiers who valued the safety of their loved ones over loyalty to their empire. At the Battle of Shawasha, Spain one a victory even greater than their victory at Mabila. Now, access to the Mississippi River and the empire's heartland were exposed. The fortress had been breached.

At the time Columbus first arrived in the New World, Shawasha was one of the largest cities in the empire, second only to Cahoqua. According to imperial censuses at the time, the city was home to around 300,000 people. Its location where the river system that held together tens of millions of people met the busy and vibrant South Misian Sea made the city wealthy as a key center of trade. Although most of the population was Hileni Misian, there were large communities of Tainos, Mayans, and Nawas, some even living in the inner portions of the city (although most tended to live in the outer portions closer to the docks). There are records of Misian bureaucrats in southern Shawasha who would go to the minority neighborhoods to try the foreign cuisine and drink balche. One record even tells of a young Misian scholar who was kicked out of a Mayan tavern for mocking Mayan culture and asking for human flesh, in reference to the admittedly accurate stereotype of Mayans practicing human sacrifice. In reality, many local ethnic Mayans had adopted the Midewin religion. Still, Taino and Mesoamerican temples existed alongside those of the Midewin faith.

Like other cities in the New World, Misia was hit hard by the plague, especially given its enormous population and its status as a center of New World trade. While the population may have been brought down to as little as 50,000, the massive amount of available food and resources made city dwelling even easier and encouraged further trade. From both migration and high birth rates, the population of Misia rebounded to more than twice that amount. Some of the outermost districts beyond the walls made up of bronze colored buildings constructed out of bricks and baked clay from the river were still rather empty. Numerous inhabitants were able to move further into the inner city, with many of those now living outside of the inner walls being newer arrivals, minorities, and merchants. These merchants would often bring in goods from the nearby piers and bring them along the streets or canals to be sold in the central market.

On 7 August 1522, Cortes would begin his attack on this city on the soft underbelly of the Great Kingdom. By this point, many Misian troops had been diverted to Mabila and the border of Spanish territory on the Pikate peninsula, both of which had seen significant skirmishes. While the local generals believed that the existing garrison was enough to defend the city, they were not fully prepared for the Spanish invasion, which was even larger than the force attacking Mabila.

One defensive advantage that Shawasha held over Mabila was that while Mabila was effectively on an open bay, Shawasha was a bit up river. While it had some points that were accessible to harbors and lakes which connected to the ocean, these points were defensible. Attacking the city by land also entailed marching through difficult swampland– land in which the Misians were accustomed to maneuvering. Of course, bringing boats up the river would also leave them quite vulnerable to attack, although the river was wide enough that keeping boats in the middle of the river would give them protection from attacks on the mainland as they made their way up.

The Spanish strategy was therefore to send ships up the mouth of the Mississippi alongside several canoes. On the swampy land, Calusa soldiers and Misian defectors, mostly from Mabila and the surrounding area, would run up the course of the river attacking any Misian forces defending its run. Meanwhile, to divide the Misian defense, another group of boats would use their naval superiority to break through the straits to access Lake Chepuna to the north of the city. The Spanish would land on the shores and march through the marshy land toward the city to the south, but the local Misian forces would be able to push back the Spanish, who were unable to use many of their firearms due to the humid conditions and who were unable to make full use of their cavalry.

From the middle of the river, Spanish ships fired their canons upon the city, destroying as many structures as they could. On August 11, after the first failed land invasion of the city, Spanish troops on Lake Chepuna made another even larger landing to draw as many Misian forces as possible to the north, while another landing was made in the city from the south on the riverbank just east of the city. This time, the Spanish were able to surround Shawasha and continue to bombard its walls. The Spanish marched through the outer-portions of the city, slaughtering anyone who resisted. Using the narrow alleyways, Misian forces attempted to attack the encroaching Spanish. Cortes simply told his troops to fire back and keep marching along the main thoroughfares towards the inner walls.

Upon reaching the inner wall, the Spanish issued an ultimatum– either all of the inhabitants would surrender and convert to Christianity or everyone would be killed. Seeing how quickly the Spanish breached the city, Shawasha surrendered. Cortes then declared everyone would be baptised, and every household would have to volunteer at least one man to serve alongside the Spanish.

On the 15th, a Misian force arrived from upriver. They surrounded the city expecting to siege it and starve out the Spanish. Misian riverboats had some success boarding and sinking Spanish ships, but upon landing, the Misians were surprised to see a large force consisting of Misian soldiers who valued the safety of their loved ones over loyalty to their empire. At the Battle of Shawasha, Spain one a victory even greater than their victory at Mabila. Now, access to the Mississippi River and the empire's heartland were exposed. The fortress had been breached.

I genuinely hope that the Misians pressed into service can be given some sort of amnesty or forgiveness - that's a hellish choice to make and I could understand being re-conscripted if liberated at worst by their empire to atone for the forced action. The Spanish are clearly making themselves out to be the indisputable bad guy here. Otherwise that's going to be one hell of an army the Misians will be bearing down on Shawasha since they can now at least sail down *everything they got* down the Mississippi onto it. Even neighboring states, as the Emperor spoke on, will probably have some volunteers to boot to join in this inevitable giant army.

I do wonder - will the English get reports from the Misians into Europe on what the Spanish are doing? In OTL there were many who tried to speak up for the plight of the Amerindians of the western hemisphere. Here there's an entire civilized empire with plenty of eyewitnesses the English can bring over - the controversy Spain will suffer is undoubtedly going to be magnified by a tremendous amount to where it may have to do something to the extent of suing for peace. Doubly so if Misia can kick the Spanish out of Shawasha and Mapila.

I do wonder - will the English get reports from the Misians into Europe on what the Spanish are doing? In OTL there were many who tried to speak up for the plight of the Amerindians of the western hemisphere. Here there's an entire civilized empire with plenty of eyewitnesses the English can bring over - the controversy Spain will suffer is undoubtedly going to be magnified by a tremendous amount to where it may have to do something to the extent of suing for peace. Doubly so if Misia can kick the Spanish out of Shawasha and Mapila.

I will say– originally my plan for the war was to make this invasion a sort of epic, but after I started writing about it I realized that writing about battles and such isn't my strong suit, and that while I do enjoy writing about war among other things, it is also difficult to maintain the passion to keep writing about one single war for so long. I think within the next few chapters I'm going to wrap up the Spanish invasion arc with broader summary and a few focused vignettes and moments of story-telling. I have some pretty exciting ideas for part ii of the story that I've already started developing regarding economic, cultural, and political events in East America as well as in Mesoamerica and the Southwest that I am really looking forward to writing about.

In the timeline so far, the Spanish have colonized much of the Caribbean. The English are also colonizing Takamcook (Newfoundland), although their colonization is concentrated primarily around St. John's and they get along with the Beothuks for the most part. The English are also settling among the other East American nations, but this is for the purpose of trade rather than settler colonialism. The Portuguese are also currently in Brazil, although Brazil is more or less the same as OTL. That's all I'm gonna say for now.@JSilvy

Do you mind answering my question if the Europeans had colonies in the New World even if the Natives' civilizations were somewhat advanced?

Deleted member 147978

It seems like North America has barely become "European" and is still "Native" in civilization substance. Cool beans, then.In the timeline so far, the Spanish have colonized much of the Caribbean. The English are also colonizing Takamcook (Newfoundland), although their colonization is concentrated primarily around St. John's and they get along with the Beothuks for the most part. The English are also settling among the other East American nations, but this is for the purpose of trade rather than settler colonialism. The Portuguese are also currently in Brazil, although Brazil is more or less the same as OTL. That's all I'm gonna say for now.

How much manpower can the Spanish really deploy there? Their own population centres are on the other side of an ocean. Subverting a sizable portion of the native populace was easy against the flower-war-having human-sacrificing Aztecs, but here there's not many whom they wouldn't need to keep actively coerced. I'd expect the Spanish force to be quite fragile, an all-in sort of play with troops they cannot replenish after a phyrric victory or a defeat and native auxillaries who would turn on them at first opportunity.

Chapter 10: The Midewin Army

Chapter 10: The Midewin Army

It was a hot, muggy summer in the village of Sakikansia, a small agricultural settlement named for the blue ash trees that were so prevalent throughout the Minowasi basin and elsewhere. The town was typically quiet. Merchants would often bring excess produce from the village to feed the nearby city of Minowasi located on the Wasioto River, which flowed into the mighty Pelesipi shortly before the point where it merged with the Mihsisipi. The shade of the sakikansi trees covered the paths leading from the small town center with its shops and Midewikiam to the surrounding houses to the mills by the stream to the pens of turkeys and ducks and geese and rabbits to the maize fields where the corn stalks grew tall.

In addition to the quiet, the town was, more often than not, peaceful. While the population of the village had steadily regrown over the past couple of decades, there was still more than enough cropland and housing for everyone to live comfortably. Everyone in the village knew each other, and so disagreements were often resolved rather quickly without much of a fuss either personally or in the town hall or Mitewikiam. The village was not near any major potential battlefronts. On the occasion that an Awansachi hill tribe went raiding into the Great Kingdom, it almost never made it as far west as Sakikansia. Most villagers had rarely if ever seen a soldier, and only once in a while would a governor or imperial bureaucrat visit.

Pashektha was returning to town with his father carrying the carcass of a deer which he had shot in the woods. They walked past the fields of golden corn and red tomatoes, past the turkeys and rabbits, and into the town center where they could sell a portion of their fresh kill. All of a sudden, they heard a sound that would stop them in their tracks– the sound of hoofs getting nearer. Emerging through the trees came a man dressed in the standard corn husk fabric clothing. He pulled on the reins. The horse picked up its front legs and then placed them on the ground and stopped. The man sitting atop the horse blew into a bison horn tied onto his torso by a leather strap, alerting the entire town to his arrival with a loud boom that echoed through the sakikansiaki.

“Pesintawiyani! Pesintawiyani!” the man shouted. He reached into the leather satchel on his back and pulled out a scroll. All within earshot of the announcement gathered together.

“I come bearing a message from Emperor Mamantwensah, head of the Kilsu Dynasty, ruler of all of the Great Kingdom, protector of the Great River, master of the heavens and earth, keeper of the ways of the ancestors, and earthly son of the Great Spirit!”

The messenger unraveled the scroll, cleared his throat, and began to read.

“Pesintawiyani, to the people of the Wasioto Province. Our great homeland is under attack by a foreign army known as the Isapanoliaki. The Isapanoliaki have attacked the great city of Mapila and killed tens of thousands of men, women, and children. They have come not simply to overthrow the Kilsu, but to destroy your entire way of life. They seek to seize all of the land under your feet for themselves and kill you or sell you all into slavery like they have done on the islands of Ayiti, Kupao, and Poriken in the Southern Seas, and lay waste to all of your Mitewikiam like they have done in Pikate and in Mapila. All men of fighting age must come together to fight this threat. Every family must send at least one man of fighting age to arrive in the city of Minowasi by sundown in four days time.”

Pashektha put down the deer and turned to his father.

“I will leave in the morning.”

“My son, Minowasi is at most a day’s journey away. You can stay longer.”

“Nohsa,” he said to his father. “If we’re under attack, then how can I wait? What if they do to us what they have done in Mapila and the Southern Seas?”

“Bring some bread with you for the journey. And some deer pahtekiaki. I don’t want you to get hungry. And don’t travel alone.”

“I won’t, nohsa,” Pashektha said. “I will meet the other men tomorrow morning by the canoes and row with them to Minowasi.”

“And go to the Mitewikiam tonight with your friends to be blessed by the Nahiteh. I want to know that Keshiwia will protect you.”

“Nohsa,” Pashektha said, “I know he will. I know that Keshiwia is on our side.”

***

Following the victory at the Battle of Shawasha, the army of Cortes had only grown, and the crusaders now dominated the South Misian coast. Misian forces in the south were scattered, and there was no other nearby city of a comparable size. Rather than continue directly up the Mississippi, Cortes took the time to ravage his way through the countryside with as much of his united force as possible, beating smaller armies and bringing an increasing amount of land and resources under his control as he solidified control of the region.

Cortes was largely successful in this endeavor. Although he faced some resistance and found fighting in the swampy alluvial plains of the lower Mississippi to be difficult, he forced dozens of villages and towns to hand over men and resources and convert to Christianity, and the few that resisted were outright massacred with only a few remaining survivors to recount the events to nearby villages. Historically, Misia’s strongest armies were never in its southern regions. It was very infrequent that any sort of attack would come by sea. Usually, the largest threats came from the Great Plains to the west, the hill tribes and kingdoms to the east, and the boreal forest tribes to the north. The men of these regions were more often battle hardened and ready compared to their southern counterparts. A significant number of soldiers were still in the northeast where they were enforcing the treaty of St. John’s to the heavily militarized eastern federations.

However, the fact that they were already militarized was simply a bonus. It meant that not only could the Kilsu pull on their own troops, but also on the forces of these smaller nearby kingdoms. Including the former Wyandot who had been conquered more than 20 years prior and not including lands recently gained in the Atlantic War, the Haudenosaunee Federation had a population of around 1.2 million. While this was less than a tenth of the 18 million Misians, the Haudenosaunee also had effectively universal conscription, and thus possessed an army of tens of thousands that could be quickly raised to an even higher amount. The numbers for Tsennacommacah were quite similar, although the Wabanaki population was a fair bit smaller.

Convincing Werecomoco to join the war was surprisingly easy. Several Taino refugees had migrated up north to Chesapeake, prompting the Manatowick, the leader of the federation, to read The Taino Tragedies. The Manatowick became sympathetic to the Taino and came to fear and abhor the barbarism and expansionism of the Isapanoles. He therefore pledged that, so long as their Haudenosaunee adversary agreed to do the same, he would send troops. Their Wabanaki ally would follow suit.

The Haudenosaunee took more convincing. In order to make a decision to go to war, sachems from all five of the original nations that joined to form the federation had to agree unanimously. In a meeting with the Misian diplomats and the leaders of his rival federations, the Tadodaho agreed that he could convince the Sachems to go to war if the Misians pledged their support to help the Haudenosaunee build a canal in their territory in order to bring boats from the Great Lakes to the port of Manhattan. Although the diplomats did not really have the power to make such a guarantee, they agreed to the Tadodaho’s terms, and the Haudenosaunee Council voted to declare war on the Isapanoles.

Meanwhile, in the Misian heartland, provincial governors were tasked with conscripting soldiers from each family in every village of their jurisdiction. By late September, a force of hundreds of thousands of young men who had all received at least some training had been assembled at the city of Nicota, one of the historic imperial capitals located just east of the confluence of the Mississippi and Pellissippi Rivers and a key point which the Spanish would have to pass by on their way to Cahoqua. By October, forces from the east would also arrive in Nikota, and Emperor Mamantwensah himself would arrive to lead them. The army was incredibly diverse– Wabanakis, Tsenacommacans, Haudenosaunees, Lenapes, Englishmen, and Misians from all across the empire had all gathered on the banks of the Mississippi to fight for the fate of an entire civilization.

Meanwhile, in the south, word had arrived to Cortes that an English fleet from St. John’s had been spotted passing by the coast of the Pikate peninsula. Realizing that time was limited before the English arrived at Shawasha and Mabila, Cortes rallied his troops to march northward along the Mississippi towards the capital. Hearing that the Isapanoliaki were on their way north, the Misians prepared their defenses and waited.

Ah, good to see England standing by its newfound ally. I still hope for an understanding and amnesty of the forcibly-conscripted Misians, but otherwise I'm looking forward to seeing this clash of titans and civilizations! Incidentally - where is Sakikansia?

....and the Misians have guns and horses, I just realized. Oh BOY are the Spanish in for a rude awakening.

....and the Misians have guns and horses, I just realized. Oh BOY are the Spanish in for a rude awakening.

Sakikansia is a small village not far from the city of Minowasi, which is the OTL site of Nashville. The Wasioto is a native name for the Cumberland River.Ah, good to see England standing by its newfound ally. I still hope for an understanding and amnesty of the forcibly-conscripted Misians, but otherwise I'm looking forward to seeing this clash of titans and civilizations! Incidentally - where is Sakikansia?

....and the Misians have guns and horses, I just realized. Oh BOY are the Spanish in for a rude awakening.

Which reminds me, I’ve been thinking for a while about trying to do a province map. I’ve figured it would be based on different watersheds given how that historically would have been the primary method of travel, but I’m still figuring out exactly how I would divide that up.

So are the Misians (and allies) waging a guerrilla war with the Spanish or straight up fighting? How are the Spanish dealing with local diseases?

@JSilvy nice to see you making another Native American timeline. Adding to @traveller76, have to ask will there be any New World diseases that will be introduced to the Old World? I’m curious because the spainish conquered some of the more populated cities that happened to be near mosquito infested wetlands, America has more animal domesticates ITTL, and there are and will be lot of spainish interactions with natives.

Last edited:

Even if the English intend to play the vulture and idle until the big battle is over to later on pick off pieces from whoever loses, I doubt the Spanish are in for a good time. And I doubt that's the plan - this is a time when Spain was in ascension, and hindering the rise of any one major continental power was for centuries something the English regarded as a useful thing to do, if not a vital duty.

Threadmarks

View all 32 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 25: The Servants of Ketzalcoatl Chapter 26: The Lynx's Den Chapter 27: The Governor Wars Chapter 28: The Maquah Constitution Chapter 29: Defenestration and Colonization Chapter 30: The Blood of the Bear Chapter 31: Mimia the Great Chapter 32: Salmon and Slaves

Share: