Radar for AA Guns and for the Merivoimat

Nokia AA Gun Radar

With the success of the first Nokia Radars, Nokia was immediately asked to design, build, and test radar antenna equipment to be used with the Bofors 76mm anti-aircraft gun batteries that were the mainstay of fixed AA defences. Working under top-secret security conditions, Nokia managed to build the project ahead of schedule, and at only 44% of the estimated cost! The system was packaged in several truck and trailer loads and was by no means a mobile system. Design work began in mid-1938, and again it would appear that the Nokia effort benefitted substantially from the work completed in Germany. By October 1938, Tigerstedt had completed detailed designs (and had also spent some time with the Manager of the Ford Motor Vehicle Manufacturing Plant at Hernesaari, near Helsinki. The Ford Manager advised Tigerstedt that the paraboloid antenna could not only be made of steel, but could be stamped using auto presses; he also criticized the gearing Tigerstedt used to turn the dish, advising Tigerstedt that it was unsatisfactory on several counts, including long trains of spur gears, weight, parts non-interchangeability, and inability to achieve close accuracy.

Tigerstedt was no mechanical engineer – he asked Ford to work on the design and a small team of Ford engineers was brought in immediately. They did a complete redesign while the Nokia team continued to work on the radar receiver and transmitter design. The end result was that the system cost a mere 20% of the originally estimated per-unit cost (at 460,000 Markka per unit rather than the 2,400,000 Markka per unit originally budgeted). The Nokia team had developed an accurate system based on a klystron microwave tube operating in the range of 54 to 53 cm (553 to 566 MHz) – an extremely short wavelength for the time – with a pulse length of 2 microseconds, a peak power of 7 to 11 kW, and a PRF of 3,750 Hz. The radar used a large 7.4m paraboloid dish antenna and had a a maximum range of about 43 kilometers. Lobe switching had been added to the design to improve aiming accuracy. This was achieved by sending the signal out of one of two slightly off-centre feed horns in the middle of the antenna, the signal being switched rapidly between the two horns. Both returns were sent to an oscilloscope display, slightly delaying the signal from one of the horns. The result appeared as two closely separated "spikes" which the operator attempted to keep at the same height on the display. This system offered much faster feedback on changes in target position, and since any change in signal strength would affect both lobes equally, the operator no longer had to "hunt" for the maximum signal point. An almost identical system was used by both the United States' first gun-laying radar, the SCR-268, and the German Würzburg C Radar. Azimuth accuracy was 0.2 degress amd elevation 0.1 degrees, more than good enough for direct gun-laying.

A prototype had been built over November-December 1938, minor modifications were made after trials and production began in March 1939. One Radar unit was teamed with a heavy anti-aircraft battery of four Bofors 76mm AA Guns (the standard Finnish Heavy AA Gun by this time, built under license by Tampella), a power source and a Stromberg-built gun director. The scanning pedestal or antenna mount turned at 1,750 revolutions per minute. The system interpreted the return signal and determined direction, speed, altitude, and course of the target. Once locked on, the antenna tracked target evasive moves and synchronized the guns. The equipment was designed to cope with aircraft speeds up to 700 miles per hour, up to 60,000 feet, at a target distance of not less than eight miles. The top-secret proximity fuse which Tigerstedt had designed completed the ensemble, since it was effective if triggered within about seventy feet of the target. Gear train accuracy was fundamental to success. In a matter of months, the whole project had been taken from concept to production thanks to a small group of Finnish scientists and engineers. Nokia engineers masterminded the principal electronic features of the apparatus while Ford Finland solved pedestal mounting, dish rotation, and transportation aspects of the system.

The paraboloid reflector dish was engineered at Ford Hernesaari to be made out of steel, rather than the aluminum used in the experimental model at the Nokia Laboratory. Ford Hernesaari was asked to work out the unsolved mechanical problems of gunlaying short-wave radar, and then develop manufacturing machines, tools, processes to achieve quantity production. The AA Gun Radar required gearing that would hold to a maximum accumulated backlash of 3.375 minutes out of a total 21,600 minutes of measurement. The motor specified turned 3,600 rpm. The dish could turn a maximum of eight times per minute horizontally and less than four times per minute in elevation. Thus reductions were necessary of 472 to 1 and 1,080 to 1 respectively. So far as was known up to that time, the solution was another Ford First: a special planetary-type gear arrangement 2 and 7/16 inches thick and 6 and 7/8 inches in diameter produced a reduction to 120.8 to 1. In turn, this was made to connect with three conventional spur gears with an additional reduction of near 9 to 1, bringing total reduction to 1,080 to 1. The total reduction was completed in a smaller space than the conventional approach of using three spur gears to obtain 8 to 1 reduction. The combination of dual planet gears, in association with a fourth member, a second annulus gear, was unique as far as was known at the time. The parties involved in the project considered this engineering success one of the major contributions to the success of the antenna system.

In addition, the spinner motor required an unlubricated air seal to prevent absorption of short wave impulses by the hollow radio frequency transmission lines. The seal held six pounds of pressure, provided by a small compressor. Friction was minimized by use of a special Ford finishing process, yielding 95 percent optically-flat surfaces on the bellows and seal. The carbon disc (shades of Fluid Drive) between the housing seal and sleeve was also finished in this manner. Pedestal support castings served as dimensional foundations for the whole assembly, and thus were made to extreme accuracy. All wire harnessing was color-coded to distinguish separate circuits, totally interchangeable, machine-tape-bound, and fungus/insect resistant. Ford Engineering also designed a special 19 foot, ten-ton semi-trailer to carry all the components of the Radar. By no means were these commercial trailers, since they were much stronger.

Nokia and Ford shipped unit one to the military for accelerated testing on December 4, 1938. System two was placed in the military’s hands on December 26, 1938. Two more went to the Antiaircraft Board for preliminary trials. Because of the urgent need, Ford and Nokia continued to produce while the intensive testing proceeded and completed a further five systems during the testing period through to March 1939. By August 31, 1939, 61 systems had been shipped and all existing Heavy AA Gun Batteries were equipped with the units. Production then continued at a slower pace. The production of the Stromberg-built gun directors proved to be more of a bottleneck than production of the radars (something we will cover when we turn to looking at AA Guns in detail).

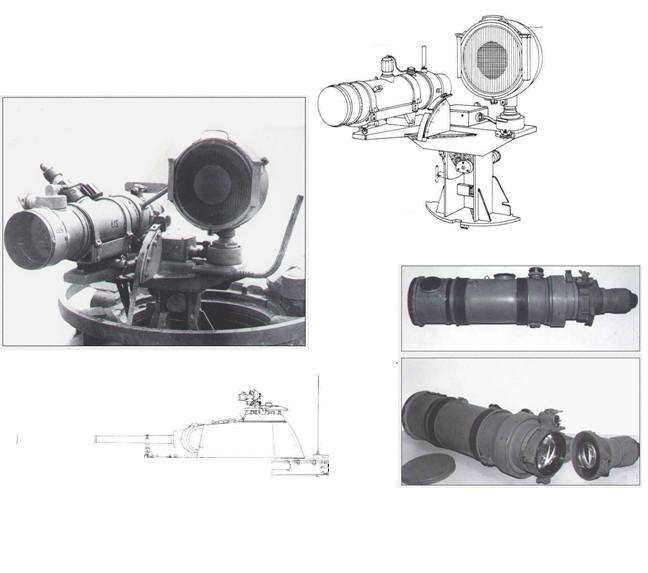

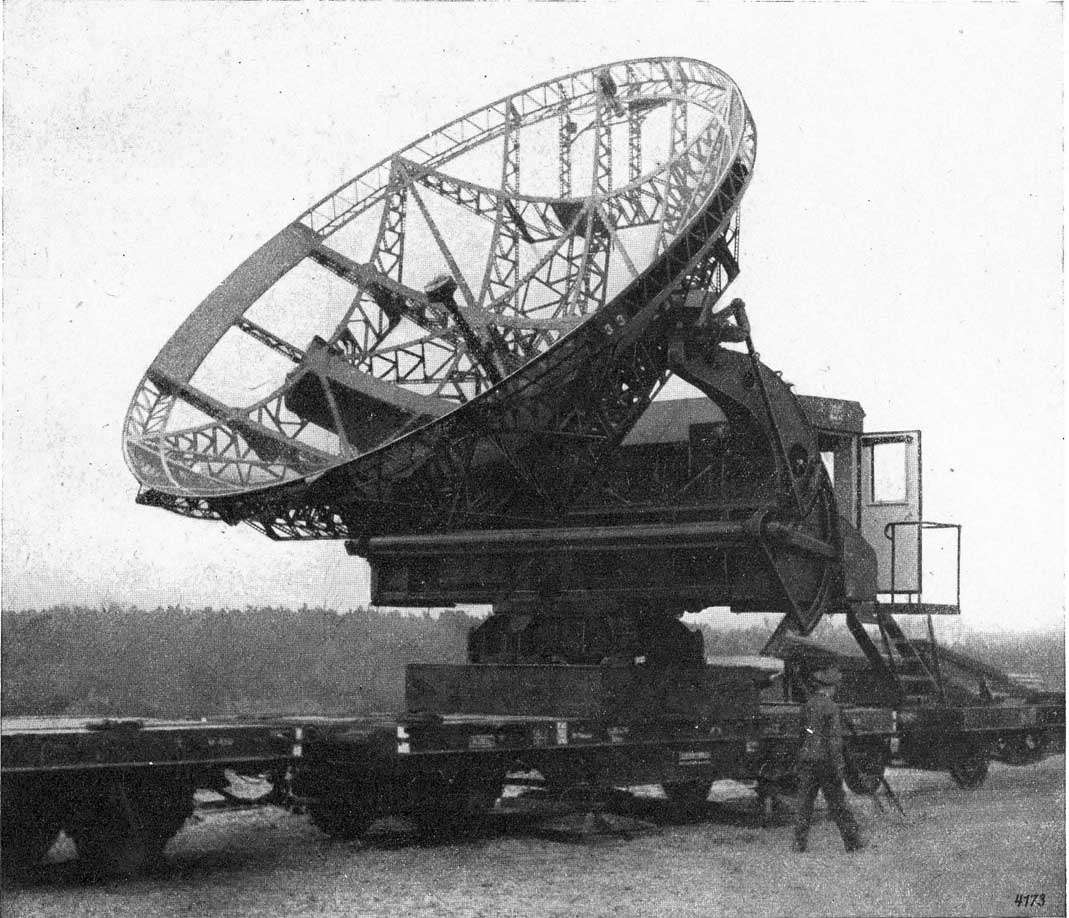

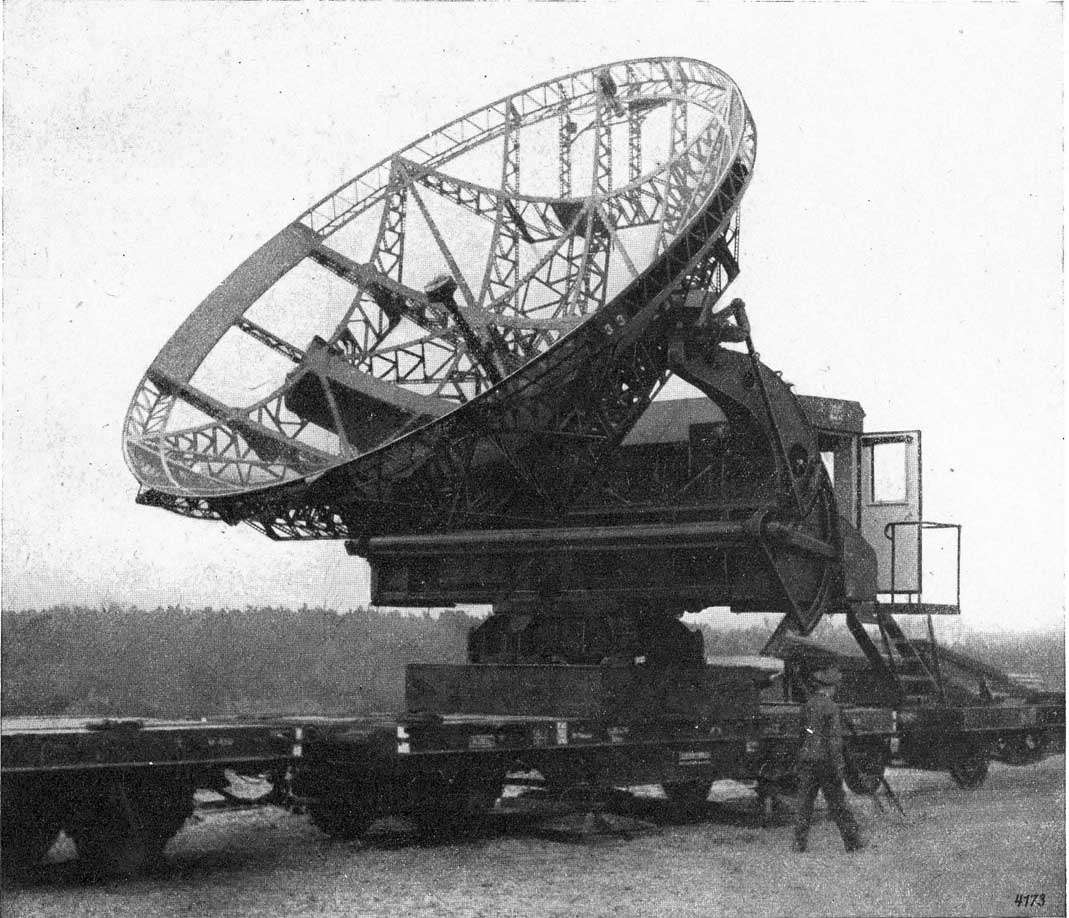

A Nokia NR-I-03/39 AA Gun Radar. The operators enjoyed the comfort of a cabin. Most NR-I-03/39’s were fixed, but the radar could also be mounted on a railway wagon for a degree of mobility.

Railway-wagon mounted Nokia NR-I-03/39 AA Gun Radar. A small number of these were used in the fighting on the Karelian Isthmus, mostly in conjunction with AA defence for the large caliber Railway Guns that the Maavoimat used in limited numbers.

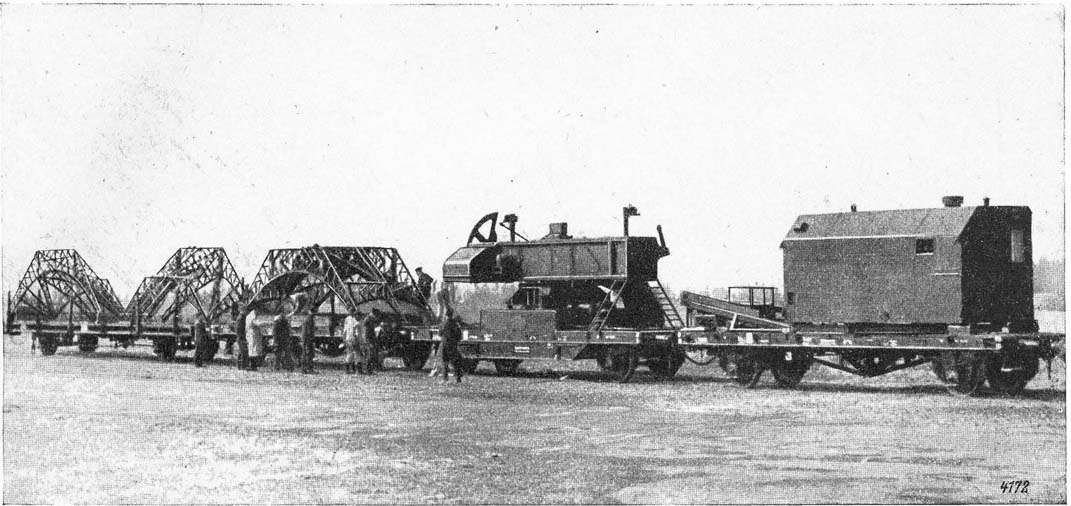

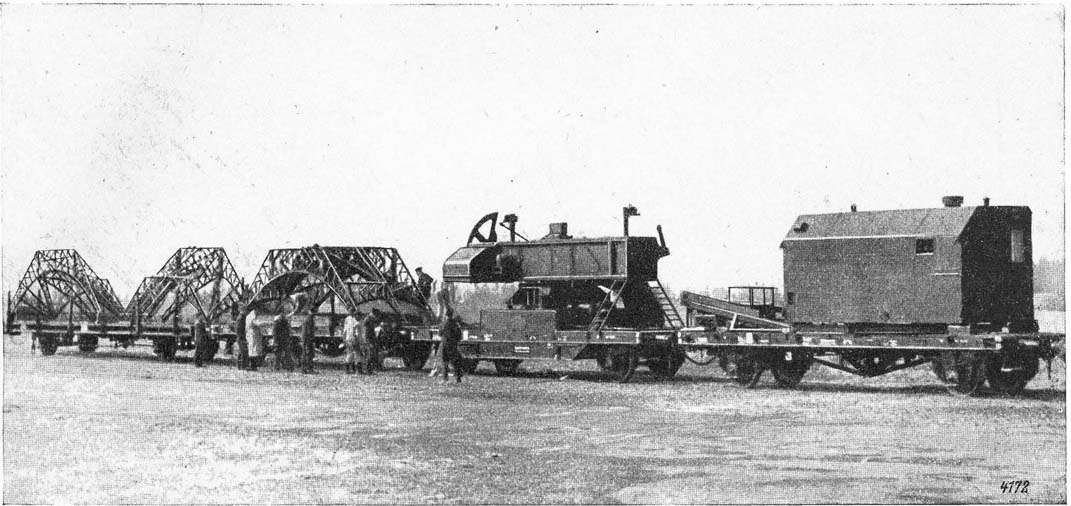

Nokia NR-I-03/39 AA Gun Radar prepared for railway transportation. The entire unit weighed approximately 25 tons.

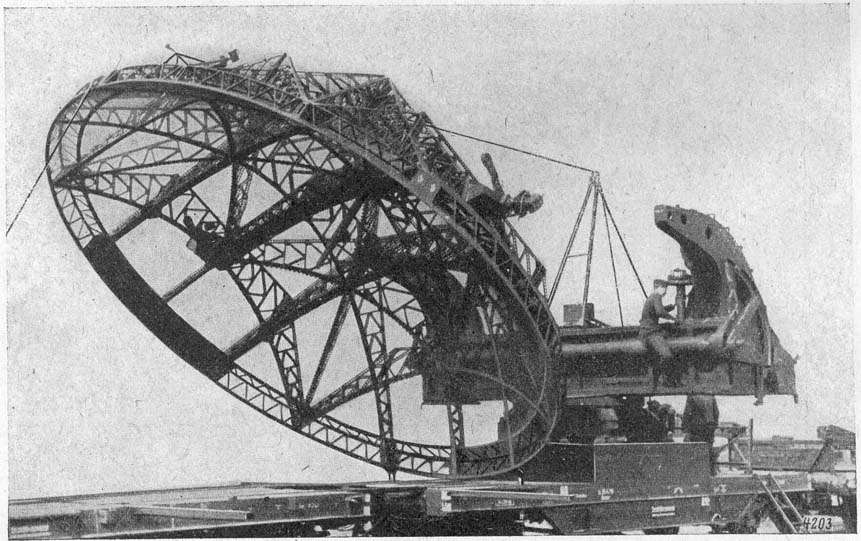

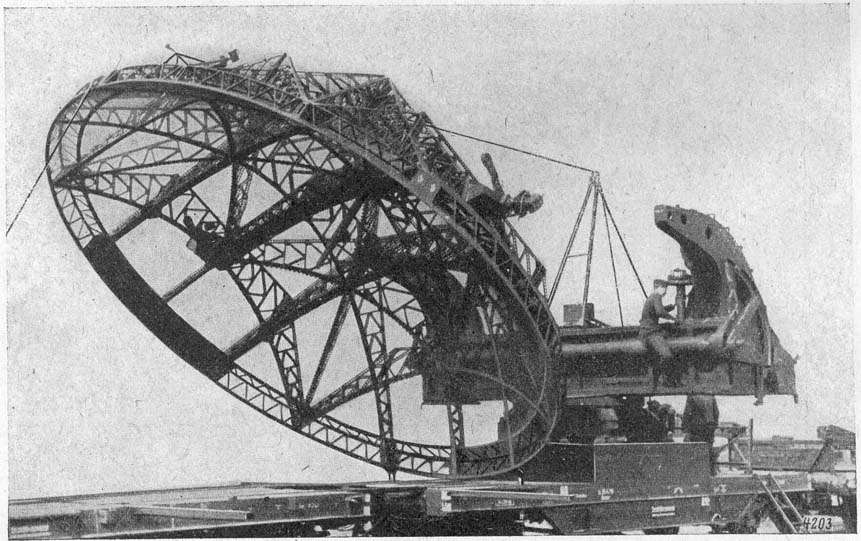

Nokia NR-I-03/39 AA Gun Radar antenna dish being mounted onto both hinge frames

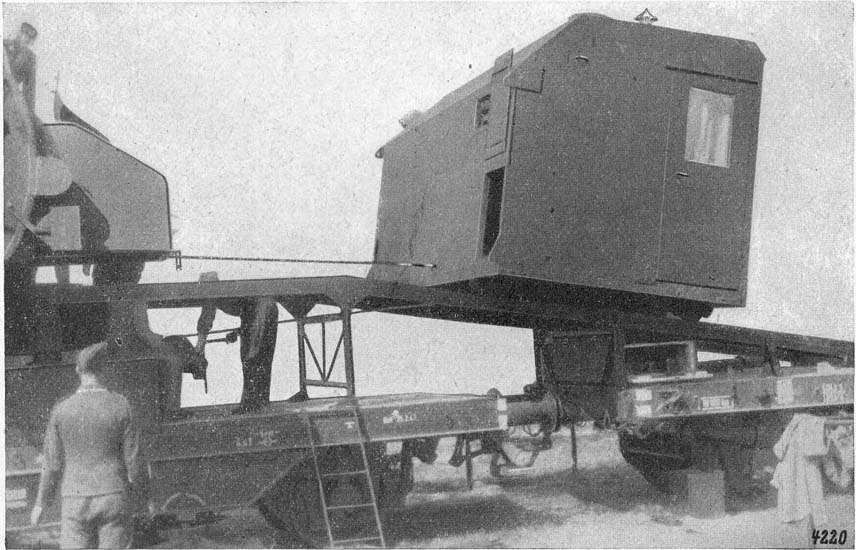

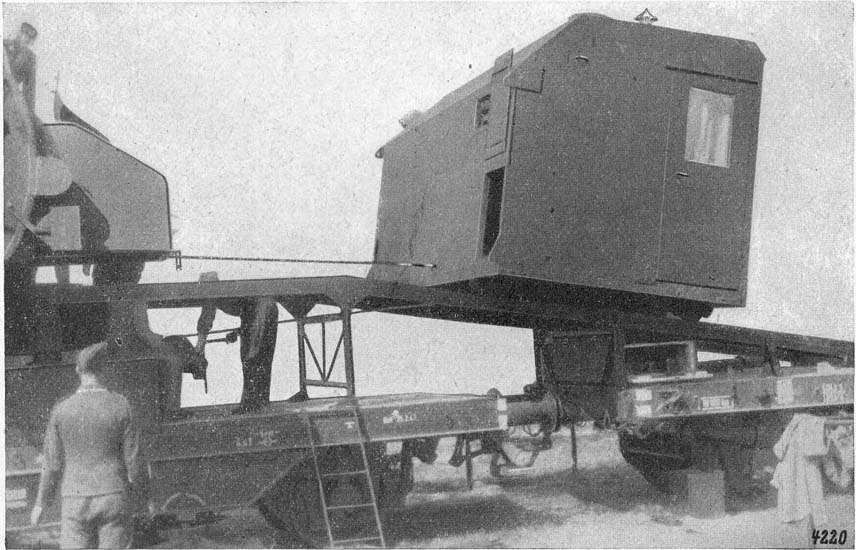

Nokia NR-I-03/39 AA Gun Radar Control Cabin being moved into place

The Nokia NR-I-03/39 achieved outstanding results in the Winter War. In all cases, use of the equipment to direct the hurling of a deluge of 76mm antiaircraft shells saved many Finnish lives, both civilian and military. Tampella continued to produce Bofors 76mm AA guns through the Winter War, resulting in a steady increase in the protection able to be offered to important industrial and military facilities as well as to the larger cities. The accuracy of Finnish AA Gun fire was already high – with the steadiy increasing use of the Nokia NR-I-03/39 combined with the new proximity fuses, it became lethal to Soviet aircraft to venture anywhere within the range of Finnish Heavy AA Gun batteries.

After the Winter War, Nokia continued to incorporate design improvements and work to reduce the size of the equipment whilst maintaining its effectiveness. The end result was by early 1944 a mobile unit needing only one truck and trailer to transport, capable of being erected and in use within twenty minutes.

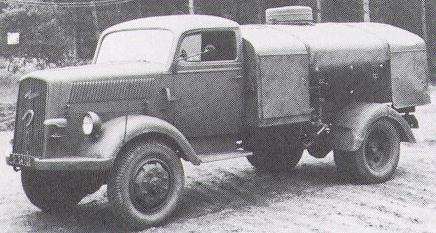

The Nokia Mobile Radar system was a truck-mounted search radar used post-1943 by Maavimat AA Gun Batteries.

Radar for the Merivoimat

With the first Nokia Radar’s proving to be effective for air and surface surveillance from coastal stations, attention turned almost immediately to the parallel development of naval versions, one for long range detection of surface and air threats, and two further types, one specifically for naval gunnery and the other for Naval AA gun control.

Long-range surveillance was perhaps the most easily addressed – the existing radar being installed in the Kotkansilmä sites was rather rapidly navalized and designated the "NR-M/01/39." Some design modifications were made to improve performance, resulting in a maximum range against a ship-sized target at sea of up to 140 miles on a good day, though rather more typically it was only half that. Still, this was a significant improvement on visual observation and worked equally as well in darkness. A prototype set was available from the Nokia team by the end of 1938, and put through successful sea trials in early-1939. The "NR-M/01/39" sets began to be installed on Merivoimat Destroyers starting in mid-1939, following which the sets were then installed progressively on the ASW Corvettes and Icebreakers.

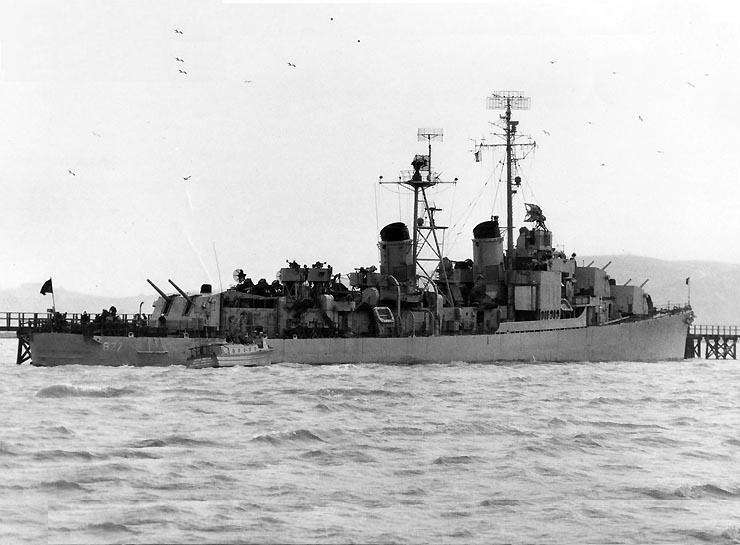

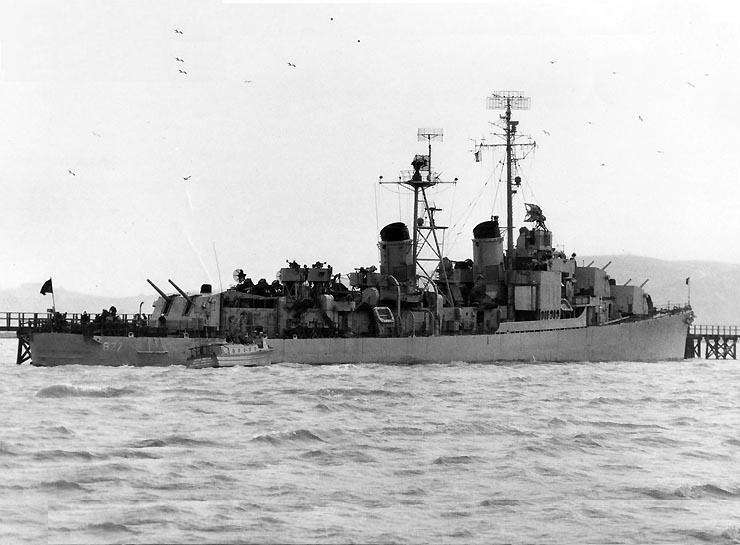

Finnish Grom-class Destroyer fitted with the long-range surveillance "NR-M/01/39", surface fire control "NR-M/02/39" and anti-aircraft fire control "NR-M/03/39" radars. By the summer of 1940, Finnish Destroyers fairly bristled with antennae of various sorts – 3 types of radar, radio and radio direction-finding aerials. They also bristled with AA Guns.

A substantial effort went into the development of a Radar that could be used for naval gunfire control. Designs for a production set for long-range surveillance, "NR-M/01/39", surface fire control, the "NR-M/02/39", and for anti-aircraft fire control, the "NR-M/03/39", were finalized shortly after the trials and all were in place in January 1940 and were being delivered to the Merivoimat and installed on ships starting from February 1940. All the Merivoimat radar types used "Yagi" antennas, essentially a row of dipoles of increasing size mounted on a rod, with the beam generated along the axis of the rod. The antennas, which workers also called "fishbones" for their appearance, were arranged at slightly different angles away from the centerline of the radar, with each side driven in an alternating fashion. The returns to each side would be different until the target was on the centerline. This technique, known as "lobe switching", could provide very precise azimuth angles. Both the NR-M/01/39and NR-M/02/39 had horizontal lobe-switching while the NR-M/03/39 also had vertical lobe-switching, which would was handy for an air-defense radar.

Maximum range against a ship-sized target at sea was up to 220 kilometers (140 mi) on a good day, though more typically half that. Performance was otherwise similar to the land-based system, with a range accuracy of about 50 m. This was considerably more accurate than the guns they ranged for, which typically had spreads of over 100 m. It was also much better than the optical rangefinding equipment of the era, which would typically be accurate to about 200 m at 20,000 m. As far as radar equipment for naval AA guns was concerned, it would have been impossible to adapt the early radar with its huge parabolic antenna and designed for heavy AA gun batteries for naval use on Destroyers and Corvettes. The equipment was simply to large and unwieldy. A decision was made to try and adapt the existing NR-M/03/39 for AA gun control. The new radar was designated the NR-M/03/39 and was a “Yagi” (mattress) style 2m x 4m antenna mounted in a yardarm. This radar also had lobe switching, giving it a high enough degree of accuracy to be useful for direction of AA guns, but the movement arc was limited and technicalities had not been fully though through at the time of the start of the Winter War.

The problem of retrofitting Radar equipment into Finnish warships was solved in various ways for each of the different types in servive. In the Grom-class destroyers, a new Radar cabin was generally shoe-horned in behind the bridge while the Radar mast and antenna were fitted to the existing mast. On the ASW Corvettes with their more limited space, the cabin was also located immediately behind the bridge and was a rather confined space for the equipment and personnel. Security was paramount but inconsistent in these fittings. Official photographs of the ships would have the sparsely ribbed, bird cage antenna censored from the top of the mast, whereas standard Supply Demands would have the shipment marked with the notation "for installation in the RDF cabin". Initially, each Radar-equipped ship was required to carry six additional Wireless Telegraphy (W/T) operators, two additional Wireless Telegraphy (W/T) Petty Officers and a RDF Officer, all specially trained in the use of the equipment. Radar detachments received very specialized training, including how to maintain and repair there equipment, and were also responsible for the security of the equipment. They carried sidearms, no non-detachment personnel were permitted within the Radar cabin, with the sole exceptions being the Captain and First Lieutenant of the ship. They kept very much to themselves, having little in common with the average seaman with whom they were quartered as Merivoimat security were concerned that some individuals might overhear and possibly, with careless talk, unconsciously pass on sensitive information.

Overall, Merivoimat Radar was probably the best in the world overall in late 1939, and the Merivoimat had certainly devoted time, resources and training to the effective integration of radar into maritime combat. The quality of both the equipment and the radar personnel was high. The Merivoimat’s special training facility at the Turku Naval Base which used simulated combat conditions to train naval personnel had a marked impact on the effectiveness of naval personnel in combat. Nicknamed “FNS Paniikki,” the simulator (contained within a large warehouse) combined mockups of the Bridge, Gun turrets, AA Gun positions, Engine Room, radar and radio offices and other key positions on movable platforms which could be rocked and swung to simulate conditions at sea, while movie screens portrayed simulated external views. Weather and sound conditions were also simulated, to the extent that participating personnel were often drenched in sea water and deafened by explosions, all whilst having to respond to every combination of circumstances that the training personnel could think of. Radar was quickly incorporated into the simulation and its usefulness drilled into naval officers.

Other radio-based equipment

Other radio-based equipment was also added to the warships over 1938 and 1939, all of it sharing the existing Radio and Radar cabins and all requiring additional personnel to use it. And all of it proved invaluable in the fighting to come. Aside from Radar, all Finnish warships also found themselves being fitted with modern VHF voice radios for voice communications within naval task groups and convoys (VHF radio sets for Finnish merchant ships were slowly stockpiled and personnel to used them trained – the plan was that in the event of war actually breaking out, they would be retroactively fitted into Finnish merchant ships, as indeed they were). Incidentally, a similar approach was taken to the installation of AA guns on Finnish merchant ships, with both 40mm and 20mm AA guns supposedly being stockpiled for installation on merchant ships. With this in mind, many Finnish merchant ships found gun platforms being added post October-1938 as they docked in Finland to unload and load cargo. In the event, most of the AA guns stockpiled for this purposed were actually taken over by the Maavoimat when war looked inevitable).

VHF voice radio was quickly being adopted over 1938-1939 thanks to developments in the Ilmavoimat and the tactical use of voice radio was perhaps the most important advance in wireless communications made by the Merivoimat. This explosion of voice radio reduced the amount of communication passed by flag or light signals. Erik Larsson of Turku describes some radio fittings when he joined the Merivoimat. "In 1937 when I joined the Naval Reserves, all Merivoimat destroyers were fitted with Merivoimat radio gear. When I first joined the ship, she had, in the radio office, a single tube Naval Pattern transmitter with a spark gap transmitter as a back up and a a low power transmitter and receiver for fire control purposes. All receivers were battery operated. In 1939, we got out first VHF Voice Radio which was used as a voice intercom between ships. Now, the ship had radiotelephone capability, but early in the game, only the captain or a specially designated officer was allowed to use it.”

A further piece of equipment that was also installed in 1939 was High Frequency Direction Finding (HF/DF) sets. Medium and low frequency radio signals have very long wavelengths so there is little hope of building efficient, highly directional shipboard DF antennas at these frequencies. However, at relatively short distances, even a small antenna will work because enough signal will be present for detection. Most warships of the inter-war period were fitted with direction finders whose antennas consisted of a pair of crossed loops. They were generally described as navigational in nature, but they could also be used as a means of detecting enemy transmitters “just beyond the horizon”. High frequency direction finding (HF/DF) was a relatively new development at the outbreak of hostilities in late 1938 and experience in correct operating techniques had to be gained step by painful step during the actual fighting.

The shipborne HF/DF sections were charged with the task of intercepting and reading Soviet (and later German) low-grade radiotelephone traffic. Generally speaking, operators were fluent in Russian (and later were also expected to be fluent in German). “Every large warship (in Merivoimat terms that meant Destroyers, ASW Corvettes and the ASW Patrol Boats) was provided with an HF/DF Unit for the interception and interpretation of enemy air and naval R/T on VHF. Some fifty Merivoimat warships in all were fitted with HF/DF units”.

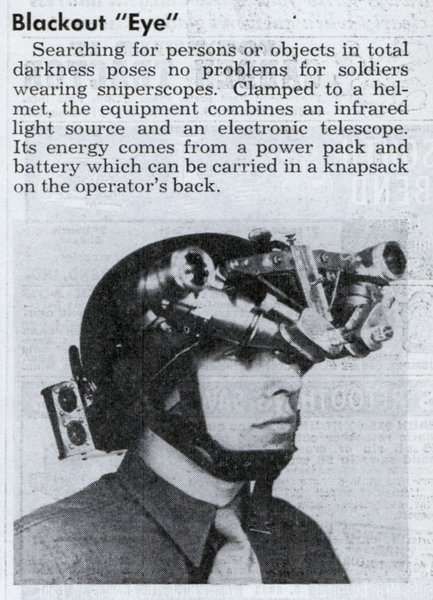

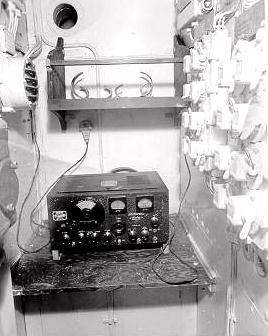

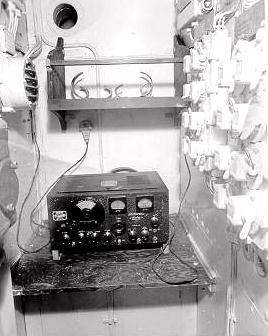

This is the actual HF/DF Office aboard a Merivoimat Grom-class Destroyer during the Winter War. Pictured is the Nokia Model 01/39 receiver unit which was only removed in 1949 (Merivoimat photo MK-1749-49)

Antti Nikulainen of Viipuri relates his experiences as an HF/DF operator. "Being a seaman a well as having knowledge of Russian (my parents were Ingrians from Leningrad who had crossed the border to Finland shortly after the Bolshevik’s took over there), I volunteered for any job where I could be of use. Once I was drafted to a ship, I was accompanied with a special Nokia VHF radio set, plus aerial and of course a copy of the code used by the enemy. On the destroyer I was assigned to, my action station was in a small office just below and aft of the bridge. Communication with the bridge was through voice pipe. Even when not at action stations monitoring the radio, I would listen in on what was happening on the bridge. On one occasion, enemy aircraft were giving a sighting report on our position while leaving Kotka and only a short time later, we were attacked by enemy bombers! On another occasion, I picked up a transmission from an enemy submarine and the Captain used that to help find the submarine, which we later attacked with a couple of other ships. We sank the submarine, which at the time I found very satisfying. Later on I volunteered for service in the new ships we were starting to get and I ended up being assigned to one the Light Cruisers we got from the Italians, fortunately not the one that was sunk by the Germans, and stayed on that as the Section Chief right through to the end of WW2. I think the most dangerous time I had was on the Helsinki Convoy when we had to fight the Germans to get through. Overall, it was a fascinating job almost guaranteeing action – and we saw plenty of that".

From the beginning of 1939, the Merivoimat had a shore based HF/DF organization in existence. The network of stations grew rapidly over 1939 to include shore stations down the length of the Gulf of Finland and on the island fortresses. Using these HF/DF stations, cross bearings could be taken by means of all these stations and fixes were plotted by the operational filter rooms. Naval ships would then be alerted and the courses of merchant ships altered, if necessary and aircraft or naval hunter-killer anti-submarine groups could be dispatched to the area of a HF/DF fix. These HF/DF stations were normally co-located with the new radar stations that were being setup at much the same time, and informationwas fed up to the same “Filter Rooms” for operational use. The addition of more shore stations and the installation of HF/DF equipmengt eventually produced a system that was amazingly accurate, particularly in identifying Soviet submarine transmissions in the Spring and Summer of 1940, when the Soviet Navy attempted unrestricted submarine warfare in the Baltic. Between using Radar and HF/DF, fixes could be quickly obtained on enemy units and then broadcast to the ASW warships at sea.

Mikael Laine of Kotka was an Anti-Submarine Warfare Officer with the Merivoimat during World War II. He gives a glimpse into the methods used to report the vicinity of Soviet (and later German) submarines. "From 1939 on, we had the Gulf of Finland and the Gulf of Bothnia lined with a network of radio direction finding stations. Later on, we established some more or less secret stations along the Swedish coast with the cooperation of the Swedish military, although I’m not sure if the Swedish government ever knew what was actually going on. Using direction finding antennas, we monitored the Soviet submarine 'reporting' frequencies. The operators copied exactly what they heard and immediately relayed that information along with date, time, frequency and bearing to a central collection point (the “Filter Room” for the naval war). This data was compared and analyzed and an approximate position of the transmission was determined and then a report was sent out immediately giving the estimated time and position of the submarine which had made identifiable transmissions. It was all submarines in 1940, after we took care of the Soviet surface fleet in December 1939. The system worked very well and was aided by the fact that the Soviets never changed frequency over the entire length of the war. We had different problems on the Atlantic Convoys to the US and on the Convoys to Britain, especially after the Germans occupied most of Norway. That was pretty tense, and we had to fight the German U-boats off, and that was a different story, I can tell you that!”

A preliminary mention of the Atlantic Theatre

The elimination of the Soviet surface Navy in the Baltic was achieved early on in the Winter War, after which the main threat was from Soviet submarines. The Merivoimat had been heavily augmented in September 1939 by the surviving Polish warships and submarines which had withdrawn to Finland (or in two cases out of the Baltic completely to Norway where they joined the Merivoimat warships based out of Lyngenfjiord). Merivoimat ASW warfare in the Baltic was particularly successful, and from Spring 1940 on submarines were not a serious threat to Finnish merchant shipping carrying cargo from Finland to Germany (a trade which continued right up until April 1944 for reasons of pure economic necessity on both sides, given that after the Helsinki Convoy of Spring 1940 there was very little love lost between the two countries). However, the Atlantic was a different story. Immediately after the outbreak of the Winter War, with access through the Baltic largely cut off, Finnish imports and exports were conducted through the Norwegian ports of Narvik and the newly constructed port of Lyngenfjiord. However, Finnish merchant shipping to and from the USA, Britain and France (and anywhere else for that matter) was at risk of attack from German U-boats which were then beginning to attack merchant ships bound for Britain.

The Merivoimat was quick to react to this threat, assigning a small number of their ASW Corvettes to operate from Lyngenfjiord, escorting convoys of Finnish merchant ships. With a very limited number of warships, the defense that could be offered was limited to start with. However, the situation improved somewhat with the two Polish destroyers arriving and them some more as the Merivoimat pressed into service two Soviet destroyers captured in a relatively undamaged condition in Murmansk. Finland had also placed orders for the construction of a small number of ASW Corvettes with a US shipyard and these were delivered impressively quickly towards the end of the Winter War, although unarmed. For Finland (although not for Norway), the situation improved further still after the German invasion of Norway, when the Finns “took over” two Norwegian Sleipner-class Destroyers that had withdrawn North in the face of the German attacks – an event which had led to Finland seizing the Finnmark, although not Narvik. After the events of the Helsinki Convoy and the Battle of Bornholm, an unmitigated disaster for the Kreigsmarine, the Germans had wisely decided to let well enough alone and had not challenged the Finnish occupation of the Finnmark, although the level of tension along the demarcation line and in the Baltic was always high.

However, this applied only in northern Norway and did nothing to stop German U-boats attacking Finnish merchant shipping in the Atlantic. A number of Finnish merchant ships were lost before the Merivoimat instituted its own convoy procedures, initially protecting Finnish ships between Lyngenfjiord and Iceland. With four ASW Corvettes, two (reflagged) Polish destroyers, the two reflagged Norwegian destroyers and the two captured Soviet destroyers, the Merivoimat could offer only a minimal level of protection.

Polish Grom-class Destroyer heading for Narvik and refuge: late September 1939

This was soon enough augmented by the conversion of twenty three Norwegian whaling boats to Convoy Escorts. Large numbers of Norwegian whalers had been laid up in Narvik and the Lofoten islands as a result of the war at sea. They were fast enough, and very seaworthy with a long range. But they were small for a warship and the armament that could be fitted was limited – generally all they carried was a light gun, usually a Tampella manufactured Bofors 76mm naval gun, fitted forward of the bridge, a couple of twin-20mm’s either side on the wings above the bridge and a Bofors 40mm AA gun immediately aft the funnel. All the stern deckspace was taken up with twin depth charge launchers and depth charges. After the guns and additional equipment such as the Radars, Radios and Asdic was fitted in, there just wasn’t that much room. The crews were far larger than they were intended for and conditions were incredibly uncomfortable, especially in winter, but the men were seamen and all volunteers – many of them the Norwegians who had originally crewed the ships – and they were all keen to join the fight one way or another.

After reaching an agreement with the Norwegian-government-in-exile, approximately twenty three Norwegian whale-chasers that were considered large enough and suitable for the work were hastily converted by the Merivoimat to ASW escorts. With the exception of their depth charges, they were lightly armed but they were fast, maneouverable, and they served to augment the larger Destroyers and ASW Corvettes in convoy escort work.

And to protect their convoys, the Merivoimat instituted some of the same techniques they had used against the Soviets in the Baltic, setting up HF/DF stations on the Norwegian coast and in Iceland. This was helped by the more frequent radio transmissions made by the German U-boats.

A Merivoimat HF/DF operator would listen on an assigned frequency. These frequencies were listed in numbered sets called a Series. Two examples of these frequencies were 10525 and 12215 kc. U-boats would generally make brief radio transmissions at regular intervals. On hearing a U-boat transmission, the intercepting operator would press a foot pedal which activated a microphone. He would then shout a coded warning to other HF/DF equipped ships to tune the intercepted frequency. After the other escorts obtained bearings, the results would be passed to the Senior Officer (SO) of the escort group and a fix obtained where possible. If it was within an estimated 15 to 20 mile radius of the convoy, the Senior Officer would send an escort chasing down the bearing. The SO would also have a message transmitted notifying the (British) shore authorities of the U-boat's bearing or position (unofficially, the Merivoimat gave as much assistance to the British as they could – the Germans on occasion protested, but the Finns simply shrugged and said “stop torpedoing our ships and we can start talking about it” and so, nothing changed.

Ashore, Mervoimat operators would listen and search on their Nokia receivers. When a U-boat's transmission was picked up, the operator on watch would immediately warn another operator at a remote site where the actual work of taking another bearing would be performed. All Merivoimat HF/DF operators knew how to recognize German transmissions and there was no dearth of signals. When German headquarters needed to communicate with U-boats, they repeated all broadcasts at one half to one hour intervals in case the transmissions were garbled. There was no need for the U- boat to signal receipt of a message. The Germans's liberal use of radio made it possible for the Merivoimat in Lyngenfjiord to realistically make hour-to-hour tactical decisions then transmit those decisions to Convoy Escort Commanders at sea.

The Finnish convoys themselves ran on routes well away from the usual U-boat hunting grounds where they could, but this was often not possible, and the U-boats themselves made no effort to differentiate between convoys bound for the UK, or those bound for Lygnefjiord. But the story of Finland’s Atlantic Convoys is for another day…

Next Post: Verenimijä

Nokia AA Gun Radar

With the success of the first Nokia Radars, Nokia was immediately asked to design, build, and test radar antenna equipment to be used with the Bofors 76mm anti-aircraft gun batteries that were the mainstay of fixed AA defences. Working under top-secret security conditions, Nokia managed to build the project ahead of schedule, and at only 44% of the estimated cost! The system was packaged in several truck and trailer loads and was by no means a mobile system. Design work began in mid-1938, and again it would appear that the Nokia effort benefitted substantially from the work completed in Germany. By October 1938, Tigerstedt had completed detailed designs (and had also spent some time with the Manager of the Ford Motor Vehicle Manufacturing Plant at Hernesaari, near Helsinki. The Ford Manager advised Tigerstedt that the paraboloid antenna could not only be made of steel, but could be stamped using auto presses; he also criticized the gearing Tigerstedt used to turn the dish, advising Tigerstedt that it was unsatisfactory on several counts, including long trains of spur gears, weight, parts non-interchangeability, and inability to achieve close accuracy.

Tigerstedt was no mechanical engineer – he asked Ford to work on the design and a small team of Ford engineers was brought in immediately. They did a complete redesign while the Nokia team continued to work on the radar receiver and transmitter design. The end result was that the system cost a mere 20% of the originally estimated per-unit cost (at 460,000 Markka per unit rather than the 2,400,000 Markka per unit originally budgeted). The Nokia team had developed an accurate system based on a klystron microwave tube operating in the range of 54 to 53 cm (553 to 566 MHz) – an extremely short wavelength for the time – with a pulse length of 2 microseconds, a peak power of 7 to 11 kW, and a PRF of 3,750 Hz. The radar used a large 7.4m paraboloid dish antenna and had a a maximum range of about 43 kilometers. Lobe switching had been added to the design to improve aiming accuracy. This was achieved by sending the signal out of one of two slightly off-centre feed horns in the middle of the antenna, the signal being switched rapidly between the two horns. Both returns were sent to an oscilloscope display, slightly delaying the signal from one of the horns. The result appeared as two closely separated "spikes" which the operator attempted to keep at the same height on the display. This system offered much faster feedback on changes in target position, and since any change in signal strength would affect both lobes equally, the operator no longer had to "hunt" for the maximum signal point. An almost identical system was used by both the United States' first gun-laying radar, the SCR-268, and the German Würzburg C Radar. Azimuth accuracy was 0.2 degress amd elevation 0.1 degrees, more than good enough for direct gun-laying.

A prototype had been built over November-December 1938, minor modifications were made after trials and production began in March 1939. One Radar unit was teamed with a heavy anti-aircraft battery of four Bofors 76mm AA Guns (the standard Finnish Heavy AA Gun by this time, built under license by Tampella), a power source and a Stromberg-built gun director. The scanning pedestal or antenna mount turned at 1,750 revolutions per minute. The system interpreted the return signal and determined direction, speed, altitude, and course of the target. Once locked on, the antenna tracked target evasive moves and synchronized the guns. The equipment was designed to cope with aircraft speeds up to 700 miles per hour, up to 60,000 feet, at a target distance of not less than eight miles. The top-secret proximity fuse which Tigerstedt had designed completed the ensemble, since it was effective if triggered within about seventy feet of the target. Gear train accuracy was fundamental to success. In a matter of months, the whole project had been taken from concept to production thanks to a small group of Finnish scientists and engineers. Nokia engineers masterminded the principal electronic features of the apparatus while Ford Finland solved pedestal mounting, dish rotation, and transportation aspects of the system.

The paraboloid reflector dish was engineered at Ford Hernesaari to be made out of steel, rather than the aluminum used in the experimental model at the Nokia Laboratory. Ford Hernesaari was asked to work out the unsolved mechanical problems of gunlaying short-wave radar, and then develop manufacturing machines, tools, processes to achieve quantity production. The AA Gun Radar required gearing that would hold to a maximum accumulated backlash of 3.375 minutes out of a total 21,600 minutes of measurement. The motor specified turned 3,600 rpm. The dish could turn a maximum of eight times per minute horizontally and less than four times per minute in elevation. Thus reductions were necessary of 472 to 1 and 1,080 to 1 respectively. So far as was known up to that time, the solution was another Ford First: a special planetary-type gear arrangement 2 and 7/16 inches thick and 6 and 7/8 inches in diameter produced a reduction to 120.8 to 1. In turn, this was made to connect with three conventional spur gears with an additional reduction of near 9 to 1, bringing total reduction to 1,080 to 1. The total reduction was completed in a smaller space than the conventional approach of using three spur gears to obtain 8 to 1 reduction. The combination of dual planet gears, in association with a fourth member, a second annulus gear, was unique as far as was known at the time. The parties involved in the project considered this engineering success one of the major contributions to the success of the antenna system.

In addition, the spinner motor required an unlubricated air seal to prevent absorption of short wave impulses by the hollow radio frequency transmission lines. The seal held six pounds of pressure, provided by a small compressor. Friction was minimized by use of a special Ford finishing process, yielding 95 percent optically-flat surfaces on the bellows and seal. The carbon disc (shades of Fluid Drive) between the housing seal and sleeve was also finished in this manner. Pedestal support castings served as dimensional foundations for the whole assembly, and thus were made to extreme accuracy. All wire harnessing was color-coded to distinguish separate circuits, totally interchangeable, machine-tape-bound, and fungus/insect resistant. Ford Engineering also designed a special 19 foot, ten-ton semi-trailer to carry all the components of the Radar. By no means were these commercial trailers, since they were much stronger.

Nokia and Ford shipped unit one to the military for accelerated testing on December 4, 1938. System two was placed in the military’s hands on December 26, 1938. Two more went to the Antiaircraft Board for preliminary trials. Because of the urgent need, Ford and Nokia continued to produce while the intensive testing proceeded and completed a further five systems during the testing period through to March 1939. By August 31, 1939, 61 systems had been shipped and all existing Heavy AA Gun Batteries were equipped with the units. Production then continued at a slower pace. The production of the Stromberg-built gun directors proved to be more of a bottleneck than production of the radars (something we will cover when we turn to looking at AA Guns in detail).

A Nokia NR-I-03/39 AA Gun Radar. The operators enjoyed the comfort of a cabin. Most NR-I-03/39’s were fixed, but the radar could also be mounted on a railway wagon for a degree of mobility.

Railway-wagon mounted Nokia NR-I-03/39 AA Gun Radar. A small number of these were used in the fighting on the Karelian Isthmus, mostly in conjunction with AA defence for the large caliber Railway Guns that the Maavoimat used in limited numbers.

Nokia NR-I-03/39 AA Gun Radar prepared for railway transportation. The entire unit weighed approximately 25 tons.

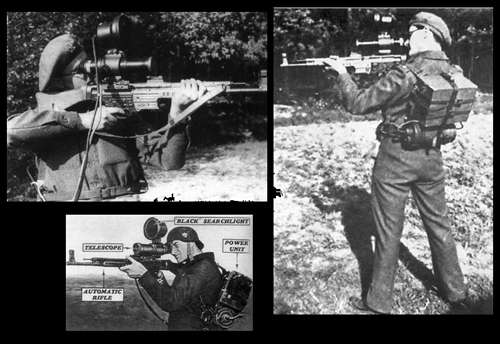

Nokia NR-I-03/39 AA Gun Radar antenna dish being mounted onto both hinge frames

Nokia NR-I-03/39 AA Gun Radar Control Cabin being moved into place

The Nokia NR-I-03/39 achieved outstanding results in the Winter War. In all cases, use of the equipment to direct the hurling of a deluge of 76mm antiaircraft shells saved many Finnish lives, both civilian and military. Tampella continued to produce Bofors 76mm AA guns through the Winter War, resulting in a steady increase in the protection able to be offered to important industrial and military facilities as well as to the larger cities. The accuracy of Finnish AA Gun fire was already high – with the steadiy increasing use of the Nokia NR-I-03/39 combined with the new proximity fuses, it became lethal to Soviet aircraft to venture anywhere within the range of Finnish Heavy AA Gun batteries.

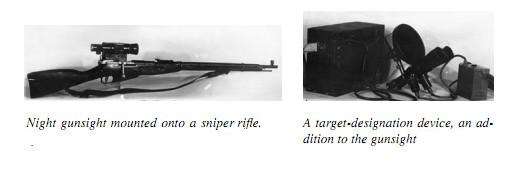

After the Winter War, Nokia continued to incorporate design improvements and work to reduce the size of the equipment whilst maintaining its effectiveness. The end result was by early 1944 a mobile unit needing only one truck and trailer to transport, capable of being erected and in use within twenty minutes.

The Nokia Mobile Radar system was a truck-mounted search radar used post-1943 by Maavimat AA Gun Batteries.

Radar for the Merivoimat

With the first Nokia Radar’s proving to be effective for air and surface surveillance from coastal stations, attention turned almost immediately to the parallel development of naval versions, one for long range detection of surface and air threats, and two further types, one specifically for naval gunnery and the other for Naval AA gun control.

Long-range surveillance was perhaps the most easily addressed – the existing radar being installed in the Kotkansilmä sites was rather rapidly navalized and designated the "NR-M/01/39." Some design modifications were made to improve performance, resulting in a maximum range against a ship-sized target at sea of up to 140 miles on a good day, though rather more typically it was only half that. Still, this was a significant improvement on visual observation and worked equally as well in darkness. A prototype set was available from the Nokia team by the end of 1938, and put through successful sea trials in early-1939. The "NR-M/01/39" sets began to be installed on Merivoimat Destroyers starting in mid-1939, following which the sets were then installed progressively on the ASW Corvettes and Icebreakers.

Finnish Grom-class Destroyer fitted with the long-range surveillance "NR-M/01/39", surface fire control "NR-M/02/39" and anti-aircraft fire control "NR-M/03/39" radars. By the summer of 1940, Finnish Destroyers fairly bristled with antennae of various sorts – 3 types of radar, radio and radio direction-finding aerials. They also bristled with AA Guns.

A substantial effort went into the development of a Radar that could be used for naval gunfire control. Designs for a production set for long-range surveillance, "NR-M/01/39", surface fire control, the "NR-M/02/39", and for anti-aircraft fire control, the "NR-M/03/39", were finalized shortly after the trials and all were in place in January 1940 and were being delivered to the Merivoimat and installed on ships starting from February 1940. All the Merivoimat radar types used "Yagi" antennas, essentially a row of dipoles of increasing size mounted on a rod, with the beam generated along the axis of the rod. The antennas, which workers also called "fishbones" for their appearance, were arranged at slightly different angles away from the centerline of the radar, with each side driven in an alternating fashion. The returns to each side would be different until the target was on the centerline. This technique, known as "lobe switching", could provide very precise azimuth angles. Both the NR-M/01/39and NR-M/02/39 had horizontal lobe-switching while the NR-M/03/39 also had vertical lobe-switching, which would was handy for an air-defense radar.

Maximum range against a ship-sized target at sea was up to 220 kilometers (140 mi) on a good day, though more typically half that. Performance was otherwise similar to the land-based system, with a range accuracy of about 50 m. This was considerably more accurate than the guns they ranged for, which typically had spreads of over 100 m. It was also much better than the optical rangefinding equipment of the era, which would typically be accurate to about 200 m at 20,000 m. As far as radar equipment for naval AA guns was concerned, it would have been impossible to adapt the early radar with its huge parabolic antenna and designed for heavy AA gun batteries for naval use on Destroyers and Corvettes. The equipment was simply to large and unwieldy. A decision was made to try and adapt the existing NR-M/03/39 for AA gun control. The new radar was designated the NR-M/03/39 and was a “Yagi” (mattress) style 2m x 4m antenna mounted in a yardarm. This radar also had lobe switching, giving it a high enough degree of accuracy to be useful for direction of AA guns, but the movement arc was limited and technicalities had not been fully though through at the time of the start of the Winter War.

The problem of retrofitting Radar equipment into Finnish warships was solved in various ways for each of the different types in servive. In the Grom-class destroyers, a new Radar cabin was generally shoe-horned in behind the bridge while the Radar mast and antenna were fitted to the existing mast. On the ASW Corvettes with their more limited space, the cabin was also located immediately behind the bridge and was a rather confined space for the equipment and personnel. Security was paramount but inconsistent in these fittings. Official photographs of the ships would have the sparsely ribbed, bird cage antenna censored from the top of the mast, whereas standard Supply Demands would have the shipment marked with the notation "for installation in the RDF cabin". Initially, each Radar-equipped ship was required to carry six additional Wireless Telegraphy (W/T) operators, two additional Wireless Telegraphy (W/T) Petty Officers and a RDF Officer, all specially trained in the use of the equipment. Radar detachments received very specialized training, including how to maintain and repair there equipment, and were also responsible for the security of the equipment. They carried sidearms, no non-detachment personnel were permitted within the Radar cabin, with the sole exceptions being the Captain and First Lieutenant of the ship. They kept very much to themselves, having little in common with the average seaman with whom they were quartered as Merivoimat security were concerned that some individuals might overhear and possibly, with careless talk, unconsciously pass on sensitive information.

Overall, Merivoimat Radar was probably the best in the world overall in late 1939, and the Merivoimat had certainly devoted time, resources and training to the effective integration of radar into maritime combat. The quality of both the equipment and the radar personnel was high. The Merivoimat’s special training facility at the Turku Naval Base which used simulated combat conditions to train naval personnel had a marked impact on the effectiveness of naval personnel in combat. Nicknamed “FNS Paniikki,” the simulator (contained within a large warehouse) combined mockups of the Bridge, Gun turrets, AA Gun positions, Engine Room, radar and radio offices and other key positions on movable platforms which could be rocked and swung to simulate conditions at sea, while movie screens portrayed simulated external views. Weather and sound conditions were also simulated, to the extent that participating personnel were often drenched in sea water and deafened by explosions, all whilst having to respond to every combination of circumstances that the training personnel could think of. Radar was quickly incorporated into the simulation and its usefulness drilled into naval officers.

Other radio-based equipment

Other radio-based equipment was also added to the warships over 1938 and 1939, all of it sharing the existing Radio and Radar cabins and all requiring additional personnel to use it. And all of it proved invaluable in the fighting to come. Aside from Radar, all Finnish warships also found themselves being fitted with modern VHF voice radios for voice communications within naval task groups and convoys (VHF radio sets for Finnish merchant ships were slowly stockpiled and personnel to used them trained – the plan was that in the event of war actually breaking out, they would be retroactively fitted into Finnish merchant ships, as indeed they were). Incidentally, a similar approach was taken to the installation of AA guns on Finnish merchant ships, with both 40mm and 20mm AA guns supposedly being stockpiled for installation on merchant ships. With this in mind, many Finnish merchant ships found gun platforms being added post October-1938 as they docked in Finland to unload and load cargo. In the event, most of the AA guns stockpiled for this purposed were actually taken over by the Maavoimat when war looked inevitable).

VHF voice radio was quickly being adopted over 1938-1939 thanks to developments in the Ilmavoimat and the tactical use of voice radio was perhaps the most important advance in wireless communications made by the Merivoimat. This explosion of voice radio reduced the amount of communication passed by flag or light signals. Erik Larsson of Turku describes some radio fittings when he joined the Merivoimat. "In 1937 when I joined the Naval Reserves, all Merivoimat destroyers were fitted with Merivoimat radio gear. When I first joined the ship, she had, in the radio office, a single tube Naval Pattern transmitter with a spark gap transmitter as a back up and a a low power transmitter and receiver for fire control purposes. All receivers were battery operated. In 1939, we got out first VHF Voice Radio which was used as a voice intercom between ships. Now, the ship had radiotelephone capability, but early in the game, only the captain or a specially designated officer was allowed to use it.”

A further piece of equipment that was also installed in 1939 was High Frequency Direction Finding (HF/DF) sets. Medium and low frequency radio signals have very long wavelengths so there is little hope of building efficient, highly directional shipboard DF antennas at these frequencies. However, at relatively short distances, even a small antenna will work because enough signal will be present for detection. Most warships of the inter-war period were fitted with direction finders whose antennas consisted of a pair of crossed loops. They were generally described as navigational in nature, but they could also be used as a means of detecting enemy transmitters “just beyond the horizon”. High frequency direction finding (HF/DF) was a relatively new development at the outbreak of hostilities in late 1938 and experience in correct operating techniques had to be gained step by painful step during the actual fighting.

The shipborne HF/DF sections were charged with the task of intercepting and reading Soviet (and later German) low-grade radiotelephone traffic. Generally speaking, operators were fluent in Russian (and later were also expected to be fluent in German). “Every large warship (in Merivoimat terms that meant Destroyers, ASW Corvettes and the ASW Patrol Boats) was provided with an HF/DF Unit for the interception and interpretation of enemy air and naval R/T on VHF. Some fifty Merivoimat warships in all were fitted with HF/DF units”.

This is the actual HF/DF Office aboard a Merivoimat Grom-class Destroyer during the Winter War. Pictured is the Nokia Model 01/39 receiver unit which was only removed in 1949 (Merivoimat photo MK-1749-49)

Antti Nikulainen of Viipuri relates his experiences as an HF/DF operator. "Being a seaman a well as having knowledge of Russian (my parents were Ingrians from Leningrad who had crossed the border to Finland shortly after the Bolshevik’s took over there), I volunteered for any job where I could be of use. Once I was drafted to a ship, I was accompanied with a special Nokia VHF radio set, plus aerial and of course a copy of the code used by the enemy. On the destroyer I was assigned to, my action station was in a small office just below and aft of the bridge. Communication with the bridge was through voice pipe. Even when not at action stations monitoring the radio, I would listen in on what was happening on the bridge. On one occasion, enemy aircraft were giving a sighting report on our position while leaving Kotka and only a short time later, we were attacked by enemy bombers! On another occasion, I picked up a transmission from an enemy submarine and the Captain used that to help find the submarine, which we later attacked with a couple of other ships. We sank the submarine, which at the time I found very satisfying. Later on I volunteered for service in the new ships we were starting to get and I ended up being assigned to one the Light Cruisers we got from the Italians, fortunately not the one that was sunk by the Germans, and stayed on that as the Section Chief right through to the end of WW2. I think the most dangerous time I had was on the Helsinki Convoy when we had to fight the Germans to get through. Overall, it was a fascinating job almost guaranteeing action – and we saw plenty of that".

From the beginning of 1939, the Merivoimat had a shore based HF/DF organization in existence. The network of stations grew rapidly over 1939 to include shore stations down the length of the Gulf of Finland and on the island fortresses. Using these HF/DF stations, cross bearings could be taken by means of all these stations and fixes were plotted by the operational filter rooms. Naval ships would then be alerted and the courses of merchant ships altered, if necessary and aircraft or naval hunter-killer anti-submarine groups could be dispatched to the area of a HF/DF fix. These HF/DF stations were normally co-located with the new radar stations that were being setup at much the same time, and informationwas fed up to the same “Filter Rooms” for operational use. The addition of more shore stations and the installation of HF/DF equipmengt eventually produced a system that was amazingly accurate, particularly in identifying Soviet submarine transmissions in the Spring and Summer of 1940, when the Soviet Navy attempted unrestricted submarine warfare in the Baltic. Between using Radar and HF/DF, fixes could be quickly obtained on enemy units and then broadcast to the ASW warships at sea.

Mikael Laine of Kotka was an Anti-Submarine Warfare Officer with the Merivoimat during World War II. He gives a glimpse into the methods used to report the vicinity of Soviet (and later German) submarines. "From 1939 on, we had the Gulf of Finland and the Gulf of Bothnia lined with a network of radio direction finding stations. Later on, we established some more or less secret stations along the Swedish coast with the cooperation of the Swedish military, although I’m not sure if the Swedish government ever knew what was actually going on. Using direction finding antennas, we monitored the Soviet submarine 'reporting' frequencies. The operators copied exactly what they heard and immediately relayed that information along with date, time, frequency and bearing to a central collection point (the “Filter Room” for the naval war). This data was compared and analyzed and an approximate position of the transmission was determined and then a report was sent out immediately giving the estimated time and position of the submarine which had made identifiable transmissions. It was all submarines in 1940, after we took care of the Soviet surface fleet in December 1939. The system worked very well and was aided by the fact that the Soviets never changed frequency over the entire length of the war. We had different problems on the Atlantic Convoys to the US and on the Convoys to Britain, especially after the Germans occupied most of Norway. That was pretty tense, and we had to fight the German U-boats off, and that was a different story, I can tell you that!”

A preliminary mention of the Atlantic Theatre

The elimination of the Soviet surface Navy in the Baltic was achieved early on in the Winter War, after which the main threat was from Soviet submarines. The Merivoimat had been heavily augmented in September 1939 by the surviving Polish warships and submarines which had withdrawn to Finland (or in two cases out of the Baltic completely to Norway where they joined the Merivoimat warships based out of Lyngenfjiord). Merivoimat ASW warfare in the Baltic was particularly successful, and from Spring 1940 on submarines were not a serious threat to Finnish merchant shipping carrying cargo from Finland to Germany (a trade which continued right up until April 1944 for reasons of pure economic necessity on both sides, given that after the Helsinki Convoy of Spring 1940 there was very little love lost between the two countries). However, the Atlantic was a different story. Immediately after the outbreak of the Winter War, with access through the Baltic largely cut off, Finnish imports and exports were conducted through the Norwegian ports of Narvik and the newly constructed port of Lyngenfjiord. However, Finnish merchant shipping to and from the USA, Britain and France (and anywhere else for that matter) was at risk of attack from German U-boats which were then beginning to attack merchant ships bound for Britain.

The Merivoimat was quick to react to this threat, assigning a small number of their ASW Corvettes to operate from Lyngenfjiord, escorting convoys of Finnish merchant ships. With a very limited number of warships, the defense that could be offered was limited to start with. However, the situation improved somewhat with the two Polish destroyers arriving and them some more as the Merivoimat pressed into service two Soviet destroyers captured in a relatively undamaged condition in Murmansk. Finland had also placed orders for the construction of a small number of ASW Corvettes with a US shipyard and these were delivered impressively quickly towards the end of the Winter War, although unarmed. For Finland (although not for Norway), the situation improved further still after the German invasion of Norway, when the Finns “took over” two Norwegian Sleipner-class Destroyers that had withdrawn North in the face of the German attacks – an event which had led to Finland seizing the Finnmark, although not Narvik. After the events of the Helsinki Convoy and the Battle of Bornholm, an unmitigated disaster for the Kreigsmarine, the Germans had wisely decided to let well enough alone and had not challenged the Finnish occupation of the Finnmark, although the level of tension along the demarcation line and in the Baltic was always high.

However, this applied only in northern Norway and did nothing to stop German U-boats attacking Finnish merchant shipping in the Atlantic. A number of Finnish merchant ships were lost before the Merivoimat instituted its own convoy procedures, initially protecting Finnish ships between Lyngenfjiord and Iceland. With four ASW Corvettes, two (reflagged) Polish destroyers, the two reflagged Norwegian destroyers and the two captured Soviet destroyers, the Merivoimat could offer only a minimal level of protection.

Polish Grom-class Destroyer heading for Narvik and refuge: late September 1939

This was soon enough augmented by the conversion of twenty three Norwegian whaling boats to Convoy Escorts. Large numbers of Norwegian whalers had been laid up in Narvik and the Lofoten islands as a result of the war at sea. They were fast enough, and very seaworthy with a long range. But they were small for a warship and the armament that could be fitted was limited – generally all they carried was a light gun, usually a Tampella manufactured Bofors 76mm naval gun, fitted forward of the bridge, a couple of twin-20mm’s either side on the wings above the bridge and a Bofors 40mm AA gun immediately aft the funnel. All the stern deckspace was taken up with twin depth charge launchers and depth charges. After the guns and additional equipment such as the Radars, Radios and Asdic was fitted in, there just wasn’t that much room. The crews were far larger than they were intended for and conditions were incredibly uncomfortable, especially in winter, but the men were seamen and all volunteers – many of them the Norwegians who had originally crewed the ships – and they were all keen to join the fight one way or another.

After reaching an agreement with the Norwegian-government-in-exile, approximately twenty three Norwegian whale-chasers that were considered large enough and suitable for the work were hastily converted by the Merivoimat to ASW escorts. With the exception of their depth charges, they were lightly armed but they were fast, maneouverable, and they served to augment the larger Destroyers and ASW Corvettes in convoy escort work.

And to protect their convoys, the Merivoimat instituted some of the same techniques they had used against the Soviets in the Baltic, setting up HF/DF stations on the Norwegian coast and in Iceland. This was helped by the more frequent radio transmissions made by the German U-boats.

A Merivoimat HF/DF operator would listen on an assigned frequency. These frequencies were listed in numbered sets called a Series. Two examples of these frequencies were 10525 and 12215 kc. U-boats would generally make brief radio transmissions at regular intervals. On hearing a U-boat transmission, the intercepting operator would press a foot pedal which activated a microphone. He would then shout a coded warning to other HF/DF equipped ships to tune the intercepted frequency. After the other escorts obtained bearings, the results would be passed to the Senior Officer (SO) of the escort group and a fix obtained where possible. If it was within an estimated 15 to 20 mile radius of the convoy, the Senior Officer would send an escort chasing down the bearing. The SO would also have a message transmitted notifying the (British) shore authorities of the U-boat's bearing or position (unofficially, the Merivoimat gave as much assistance to the British as they could – the Germans on occasion protested, but the Finns simply shrugged and said “stop torpedoing our ships and we can start talking about it” and so, nothing changed.

Ashore, Mervoimat operators would listen and search on their Nokia receivers. When a U-boat's transmission was picked up, the operator on watch would immediately warn another operator at a remote site where the actual work of taking another bearing would be performed. All Merivoimat HF/DF operators knew how to recognize German transmissions and there was no dearth of signals. When German headquarters needed to communicate with U-boats, they repeated all broadcasts at one half to one hour intervals in case the transmissions were garbled. There was no need for the U- boat to signal receipt of a message. The Germans's liberal use of radio made it possible for the Merivoimat in Lyngenfjiord to realistically make hour-to-hour tactical decisions then transmit those decisions to Convoy Escort Commanders at sea.

The Finnish convoys themselves ran on routes well away from the usual U-boat hunting grounds where they could, but this was often not possible, and the U-boats themselves made no effort to differentiate between convoys bound for the UK, or those bound for Lygnefjiord. But the story of Finland’s Atlantic Convoys is for another day…

Next Post: Verenimijä