You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

War makes for Strange Bedfellows – A Second World War timeline

- Thread starter BurkeanLibCon

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 43 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

INTERMISSION: Per Albin Hansson’s speech regarding war with Britain and France Chapter 26 – The Beast from The East Chapter 27 – Stalemate in the Sky Map of Europe, 1 September 1940 ANNOUNCEMENT LOOK INTO THE FUTURE (3) Chapter 28 – The Alliance (Part 1) Chapter 29 – Hunting High and Low

Chapter 17 - Whitehall Waltz (Part 1)

Chapter 17 – Whitehall Waltz (Part 1)

British Political Situation

May 1940

British Political Situation

May 1940

By May 1940, British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain was in a funny position. His conduct of the war so far had seen the disastrous Scandinavian expedition. Despite Norway seeing Britain’s way (after some “persuasion”), Sweden hadn’t and the fighting in the northern regions of that country (initially referred to by the press as the “Swedish War”, later known as the “Lapland War”) had turned into a quagmire that Britain had no means of exiting. Still, it hadn’t all been bad. Access to Norwegian air and naval bases and ports had made Britain’s blockade of Germany easier and Germany wasn’t receiving exports of Iron Ore from Narvik. Despite all its shortcomings, the Scandinavian operation was just successful enough for Chamberlain to cling on. On the 2nd of May, leader of the Labour Party Clement Attlee asked in the House of Commons if Chamberlain was “now able to make a statement on the position in Scandinavia [1].” Chamberlain responded by stating that “The blockade of offensive, war-making materials to Germany via Scandinavia is proceeding smoothly and efficiently [2].” Chamberlain was reluctant to further discuss, but instead asked for the issue to be deferred by a week, Attlee and Liberal Party leader Sir Archibald Sinclair agreed [3]. The same day, Chamberlain submitted a schedule of the House’s business for the next week to Attlee after the latter privately requested it. In it, a debate on the conduct of the war was scheduled for Thursday, 9th of May [4].

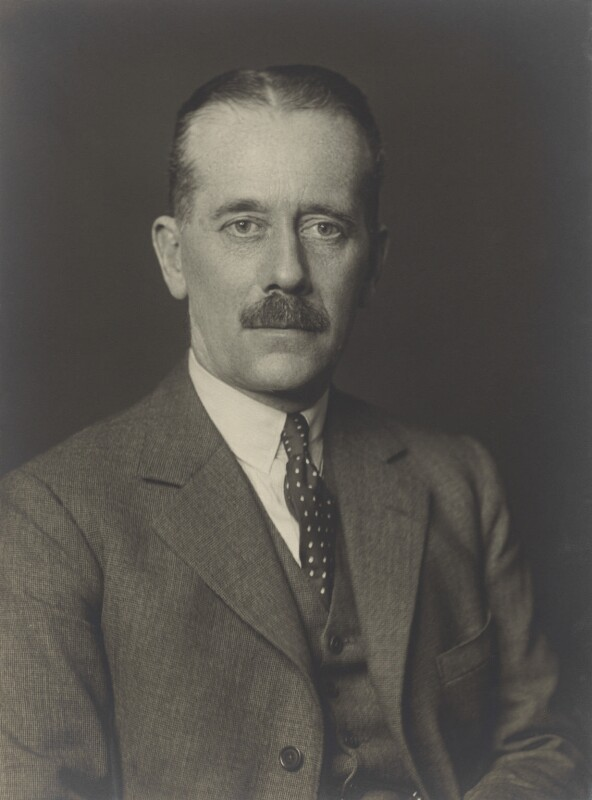

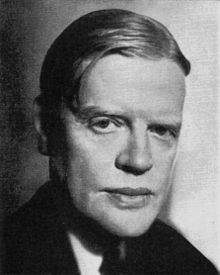

Neville Chamberlain, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

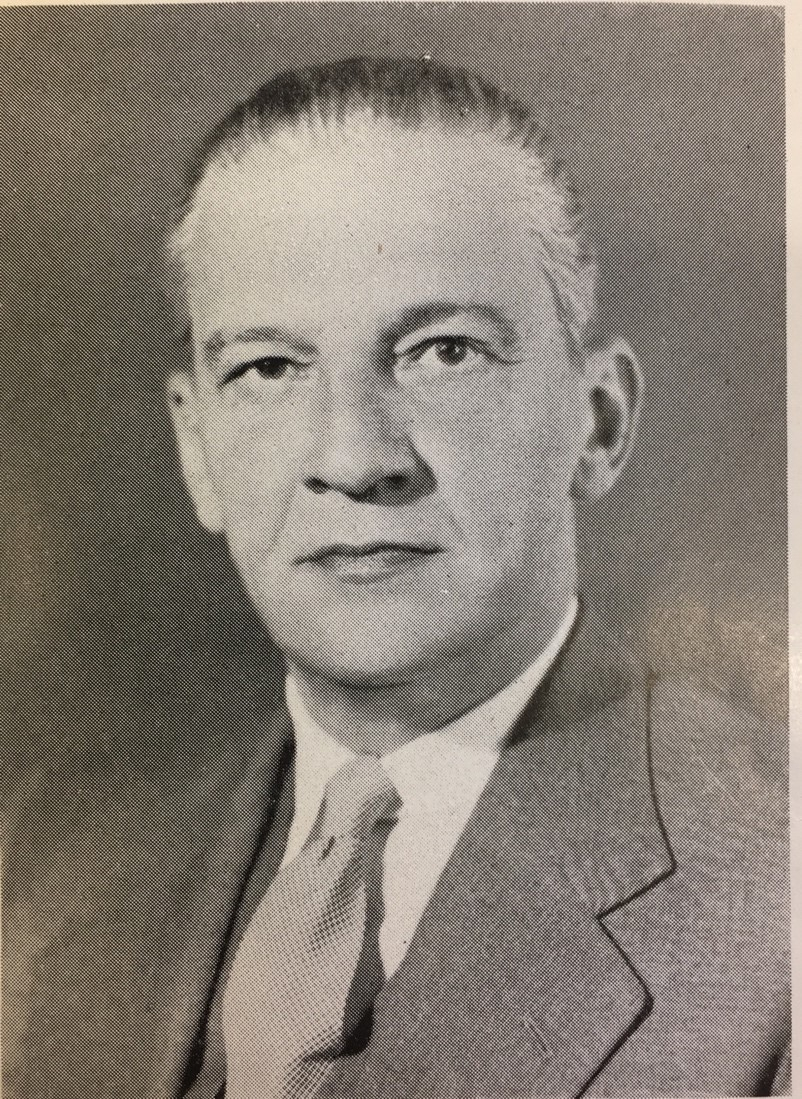

Clement Attlee, Leader of the Labour Party

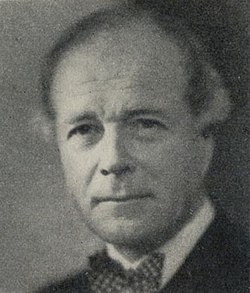

Sir Archibald Sinclair, Leader of the Liberal Party

When the day arrived, the House assembled at 14:25 with Speaker FitzRoy in the chair. After some private business matters were resolved, the adjournment motion was made by Chief Whip David Margesson at 15:03 and the House of Commons could proceed with a general “Conduct of the War” debate.

Edward FitzRoy, Speaker of the House of Commons

David Margesson, Chief Whip

Chamberlain was first to rise. He began by rehashing his statement from a week before about the blockade proceeding successfully. He then addressed the situation in Sweden by stating that “the situation in Sweden is well under control” whilst praising the “splendid gallantry and dash [5]” of British forces fighting there. Chamberlain’s speech continued by insisting that “the balance of advantage lies on our side [6]” before referring to Lord Nelson in closing: “One hundred and forty years ago, Nelson said, "I am of the opinion that the boldest measures are the safest" and that still holds good to-day [7].”

Next to speech was Attlee. He began by responding to the government’s claims of taking the initiative by saying “It is said that in this war despite initiative from our side, it is said also that there is no real planning in anticipation of the possible consequences against us.” Attlee’s speech took a certain theme from hereon in, that Chamberlain’s war cabinet had vigorously prosecuted hostilities with Germany and Russia but had done so in a foolhardy way that was diminishing Britain’s standing. He made use of Chamberlain’s expression that Hitler had “missed the bus” before his death by saying: “Until now, this government has missed every bus since 1931. Austria, Czechoslovakia and Poland. All the peace buses missed. And now we’ve caught the war bus, we’ve driven it off the Dover cliffs [8].”

Sinclair rose to speak next. He again spoke of foolhardiness in the government’s securing of Norway, which had led Sweden into the war against Britain: “It is my contention that this debacle in Sweden occurred because there had been no foresight in the political direction of the operation and in the instructions given to the Staffs to prepare for and execute it [9].”

The rest of the day saw numerous speeches both in favour of and against Chamberlain and his government. As National Labour MP and diarist Harold Nicolson noted: “The debate continued with both ends of the House throwing support for and opposition to Chamberlain throwing their cases back and forth like a tennis ball with no one side able to gain an advantage [10].”

The next day, Göring’s Germany initiated its invasion of the Low Countries and France. Suddenly, the mood in the Chamber was very different. Chamberlain addressed the House as follows:

“Mr Speaker, early this morning, without warning or excuse, the Nazis have added another horror to the already long list of horrors which disgraces their name with an attack on Holland, Belgium and Luxembourg. In all history, no other regime has been responsible for such a hideous disregard for human suffering except that of Stalin’s Russia. They have chosen a moment when it appeared that this nation was in the throes of a political crisis and divided against itself. If they have counted on our internal divisions to help them, they have miscounted the minds of our people. I will now make no comment on the debates in this House yesterday. But, it is now clear to me, in this critical moment in the war, what is needed is the formation of a government that includes the members of the Labour and Liberal opposition parties, to present a united front to the enemy. I therefore ask, Mr Speaker, that my Right Honourable colleagues Mr Attlee and Mr Sinclair join us in creating that united front. Now, before I give way, there are one or two final things I wish to say. During the past three years, as long as I believed there was a chance of preserving peace honourably, I strove to take it. When the last hope vanished, and war could no longer be avoided, I have striven to wage it with all my might. Perhaps the House will remember, Mr Speaker, in my broadcasts of September 3rd and 19th last year, I told the British people that we would be fighting evil things. My words have proved to be insufficient to describe the vileness of those who have now staked everything on the great battle just beginning. Perhaps it may at least be some relief to know that this battle, though it may last for days or even weeks, has ended the period of waiting and uncertainty. For the hour has come when we are to be put to the test, as the innocent people of Holland, Belgium and France are being tested already. And now, above all else, with our united strength, and with unshakable courage fight and work and wage war by land, sea and air with all the might that God can give us until these wild beasts, which have sprung out from their lair upon us, be finally disarmed and overthrown. You may ask, what is our policy? I can answer that in one word. Victory. Victory at all costs–Victory in spite of all terror. For without which, there is no survival, only slavery and a thousand-year slumber. [11].”

Towards the end of his speech, Chamberlain was almost bellowing with passionate fury. The response from the House of Commons was thunderous. Chamberlain was once again standing firmly on two feet. For now at least, his position was secure as the Battle of France got underway.

Footnotes

- [1] A similar remark was made by Attlee in OTL referring to the disastrous Norwegian campaign.

- [2] Here, despite the absolute debacle with Sweden, Britain’s strategic position is better than in OTL. Norway is firmly on Britain’s side with its ports and air bases open to the Royal Navy and RAF. This means that Chamberlain is more confident in his position than in OTL and doesn’t ask for the issue to be deferred.

- [3] Chamberlain asked for the issue to be deferred in OTL as well, resulting in the now-famous “Norway debate.”

- [4] In OTL, the debate was scheduled for Tuesday, 7th of May. The delay will become important later.

- [5] An OTL statement of Chamberlain’s from the Norway Debate.

- [6] This is OTL too, although here it is less of a blunder.

- [7] In OTL, this remark was made by Roger Keyes to criticise Chamberlain to “thunderous applause” in the Commons. Here, Chamberlain steals the line to buttress his position. It’s somewhat successful.

- [8] I made this one up myself, inspired by some of Attlee’s remarks during the OTL Norway Debate.

- [9] Again, inspired by Sinclair’s OTL remarks.

- [10] A massive difference from the mood of the House in OTL. Here, Chamberlain can scrape through the first day of TTLs debate as Britain’s overall position is better than OTLs. The next day, however, will bring surprises. As to the content of Nicolson’s diary entry, I made it up.

- [11] Heavily inspired by Chamberlain’s OTL resignation speech with a hint of Churchill’s “Blood Toil, Tears and Sweat” thrown in towards the end and a few additions of my own.

Part 2 of the British political story is coming soon.

Sources

Wikipedia:

Norway Debate - Wikipedia

CONDUCT OF THE WAR. (Hansard, 7 May 1940)

CONDUCT OF THE WAR. (Hansard, 7 May 1940)

api.parliament.uk

Comments?

Last edited:

thaddeus

Donor

What position is Germany and the Soviet Union going to take on the war in China? If Japan's on their side, the Soviets could help Japan with their oil crisis.

TBH I’m not that sure. I know that Göring referred to Japan as a “Far East Italy” or something along those lines and I suspect Stalin isn’t too keen on the Japanese given the recent border conflicts.

I think the course of action in the Far East depends on what Japan does regarding French Indochina and how much Stalin distrusts the Japanese. America will probably also influence the course of events here too.

think if Nazi Germany and the USSR are allied for at least the short and intermediate term, China would look more appealing as a trading partner, and Japan has less importance? (maybe the ideal scenario for the Nazi regime would be enlist both, as they did Hungary and Romania, but that seems impossible)

if the Vichy regime is established under this scenario, the idea of the Nazi regime exerting some putative authority over the Far East colonies of the Dutch might be appealing. i.e. the Nazi regime has an alliance with the USSR and Vichy France (and possible China), possibly it doesn't seem beyond their (geographic) grasp?

It seems Chamberlain might be able to hold both his position and that of England at war, hopefully he can avoid some of Churchill's pitfalls while still doing his job of keeping morale alive.

If he doesn't die first.It seems Chamberlain might be able to hold both his position and that of England at war, hopefully he can avoid some of Churchill's pitfalls while still doing his job of keeping morale alive.

It seems Chamberlain might be able to hold both his position and that of England at war, hopefully he can avoid some of Churchill's pitfalls while still doing his job of keeping morale alive.

Thing is that Neville Chamberlain died from cancer on November 1940 in OTL and this hardly changes. So there is going to be new prime minister anyway at end of the year.

Love the political parts and butterflies. Very well researched and feels real.Comments?

I've made some minor adjustments to the title page if anyone's interested in looking that far back.

Perhaps such changes could be marked, so we can easily see what's new?I've made some minor adjustments to the title page if anyone's interested in looking that far back.

All I did was make the title bigger and add a quote from Lord Chatfield. Nothing too fancy.Perhaps such changes could be marked, so we can easily see what's new?

Sorry, I meant the previous changes to those many updates. I think they were made in the text itself?All I did was make the title bigger and add a quote from Lord Chatfield. Nothing too fancy.

Oh yes, those. All I did was have the British troops in Sweden not reach Kiruna. After speaking with von Adler about it, I realised that there would be no way they'd get that far into Swedish territory.Sorry, I meant the previous changes to those many updates. I think they were made in the text itself?

Oh, thanks for explanation, I thought it was something bigger.Oh yes, those. All I did was have the British troops in Sweden not reach Kiruna. After speaking with von Adler about it, I realised that there would be no way they'd get that far into Swedish territory.

Hi @BurkeanLibCon, I just finished reading the chapters that you have written so far and I have to say that I really enjoyed them. I'm really curious to see what will happen next: Attach on Malta and Manstein in Africa? (maybe the Goering tells Italy that if they don't attack the Balkans, Germany will help Italy obtain the territories it wants from France after the end of the war?) Soviet invasion of Finland 2.0 and German-Swedish invasion of Norway? Italian invasion of Yugoslavia in September? A combination of all the above statements? I guess only time will tell...

I imagine that the Middle East and Turkey (getting their fleet out of the Black Sea and into the Med) are a higher Priority than making an SSR out of Finland. Their only serious opponent in the Middle East is Iran, and they still crushed Iran in a week even with Barbarossa going on IOTL. Turkey is harder to do but if you have the Axis members invading from the West all they need to do is hold up units in Kurdistan and the greater Armenia area. Syria is going to be a Soviet ally even quicker in this TL. The USSR and later the Russians were always interested in having such an advantageous naval position in the Mediterranean (basically a corner position and far away from the major British bases other than Cyprus, which itself is highly isolated, given it's position), but could never get it with Turkey in the way and later NATO giving them a firm NO. ITTL they can because who is gonna tell the largest industrial and military power on the Eurasion continent no? It's allies that depend on it for resources? I think not.Soviet invasion of Finland 2.0

Chapter 18 - Whitehall Waltz (Part 2)

Chapter 18 – Whitehall Waltz (Part 2)

British Political Situation

May – June 1940

British Political Situation

May – June 1940

On the 10th of May 1940, Germany invaded France and the Low Countries. In Britain, the invasion served to temporarily reinforce the position and job security of Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain. In a speech delivered to the House of Commons that day (known to future historians as the “thousand-year slumber” speech [1]), the PM had invited the opposition Labour and Liberal parties into a national unity government. Unfortunately for Chamberlain, both Attlee and Sinclair had refused, but Attlee privately agreed to attend war cabinet meetings along with deputy Labour leader Anthony Greenwood although they would have no vote [2]. By this point, the war cabinet comprised the following members:

Neville Chamberlain: Prime Minister

Sir Samuel Hoare: Secretary of State for Air

Sir John Simon: Chancellor of the Exchequer

Lord Halifax: Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs

Oliver Stanley: Secretary of State for War

Sir Kingsley Wood: Lord Privy Seal

Winston Churchill: First Lord of the Admiralty

Lord Hankey: Minister without portfolio [3]

As the Low Countries fell to the Wehrmacht and the best Allied armies became trapped around the Channel ports, it became clear in the war cabinet that a major military crisis was underway and the first rumblings of exploring a negotiated peace settlement began to emerge.

On the 24th, War Secretary Stanley reported that there were only a few specialist units of British troops in the port of Dunkirk, and that the supplies continued to be unloaded at the port. One area of interest which emerged was that of Italy. The war cabinet was interested in, if possible, keeping Italy and of the war and delaying it if that wasn’t possible. Foreign Secretary Halifax read out a proposal from Reynaud that Franklin D. Roosevelt, President of the United States, would act as a third-party by approaching Mussolini to discuss any possible territorial concerns of his [4].

Oliver Stanley, Secretary of State for War

Franklin D. Roosevelt, 32nd President of the United States

The next, the 25th, the plan was again discussed among the cabinet. Churchill by this point had emerged as its strongest opponent, but Chamberlain (influenced by Halifax) had decided to investigate it further. Since the failures of Operation Silver in March, Churchill’s influence in the war cabinet had begun to wane. Contact was made with Roosevelt at midday Washington time (16:00 GMT) requesting that the President approach the Italian government concerning Italian “security and political interests in the Mediterranean” but added that there was to be no mention of the British government origins of this request. Roosevelt consented to make the outreach.

At 13:00 local time the next day, US Ambassador to Italy, William Philipps, approached Italian Foreign Minister, Count Ciano, presenting what appeared to be an American offer to mediate Italian interests in the Mediterranean. Ciano was initially confused by the American outreach but confirmed with Philipps that he would relay the message to Mussolini. Later that afternoon, Ciano had relayed the message to Mussolini. However, Roosevelt’s offer had the precise opposite effect to what it had desired, further convincing Mussolini that the war may end very soon and thus Italy had to jump in as soon as possible. He ordered the American outreach be discarded; the Duce was not interested in negotiation anymore. When meeting Philipps the next day, May 27th, Ciano relayed that Mussolini was not interested in the offer, and that he was certain that Italian entry into the war was inevitable, just that the date could not be confirmed [5]. Philipps referred this back to the State Department, the message arriving back at the desk of Roosevelt by 09:30 eastern standard time. The message was relayed to the British ambassador, the Marquess of Lorraine, who transmitted the message to the war cabinet back in London.

William Philipps, United States Ambassador to Italy

Galeazzo Ciano, Italian Minister of Foreign Affairs

When the war cabinet reconvened, Halifax relayed to the assembled ministers that the outreach via Roosevelt had been rejected by Mussolini. Churchill felt his position had been vindicated, that reaching out to Mussolini was doomed to failure and furthermore could damage Britain’s fighting position. Furthermore, Attlee and Greenwood (a non-voting observer) agreed with the First Lord of the Admiralty. At this point, any further ideas of outreach to Berlin, Rome or Moscow were ruled out. But the possibility of outreach to one of their other allies was still openly discussed [6].

The next day, the 28th, saw both success and tragedy for Chamberlain and his government. That day saw nearly 18,000 servicemen evacuated from Dunkirk’s harbour and the beaches. However, the mood was brought down by the plane crash that killed by Hoare and Churchill [7]. Their replacements were Sir Kingsley Wood as Air Secretary and Admiral Roger Keyes as First Lord of the Admiralty, the latter appointment signalling that Britain very much intended to continue the war. Lord Hankey took Wood’s prior role as Lord Privy Seal.

Sir Kingsley Wood, Secretary of State for Air

Sir Roger Keyes, First Lord of the Admiralty

Lord Hankey, Lord Privy Seal

Chamberlain, as before, continued to trundle along. Only time would tell how long it would last.

Footnotes

- [1] See Chapter 16 for more.

- [2] I took inspiration for this arrangement from the Australian Advisory War Council of OTL.

- [3] Same composition as OTL.

- [4] Genuine proposal from the French government in OTL.

- [5] Ciano told something similar to Percy Lorraine, the British Ambassador in OTL on the 29th May when Mussolini expressed disinterest in French territorial negotiations.

- [6] Take a guess as to who that would be.

- [7] See Chapter 16 for more information.

Sources

Wikipedia

Chamberlain war ministry - Wikipedia

Advisory War Council - Wikipedia

War cabinet crisis, May 1940 - Wikipedia

Comments?

I wonder if Italy will do better in the North African campaign.

While there were problems of incompetence and political infighting within Fascist Italy, the primary problem was the shortage of modern military equipment, and the shortage of food, oil, coal, iron ore and other strategic materials. However, if Soviet Union sells (at a reasonable price) the needed strategic materials to Italy, and Germany provide Italy with more moderns tanks, self-propelled guns, APVs, fighters and bombers (because Barbarossa not happening), Italy could do much better. Plus, the British would have less military personnel available in Egypt, thanks to having to fight the Soviets (and possibly Persian and Iraqi anti-British forces) in Middle East... and the active front in Scandinavia.

Maybe in this timeline, Italy can be seen as a valuable member of the Axis, instead of the useless sidekick that constantly got kicked around before switching sides...

While there were problems of incompetence and political infighting within Fascist Italy, the primary problem was the shortage of modern military equipment, and the shortage of food, oil, coal, iron ore and other strategic materials. However, if Soviet Union sells (at a reasonable price) the needed strategic materials to Italy, and Germany provide Italy with more moderns tanks, self-propelled guns, APVs, fighters and bombers (because Barbarossa not happening), Italy could do much better. Plus, the British would have less military personnel available in Egypt, thanks to having to fight the Soviets (and possibly Persian and Iraqi anti-British forces) in Middle East... and the active front in Scandinavia.

Maybe in this timeline, Italy can be seen as a valuable member of the Axis, instead of the useless sidekick that constantly got kicked around before switching sides...

They can't have much less than OTL, given that Compass was fought with severe numbers disadvantage as it is. They will have to send much more from Britain to keep up with new commitments in Middle East and you have to wonder if invasion scare will be higher ITTL. They have to worry that Red Air Force will join Luftwaffe in Battle of Britain.Plus, the British would have less military personnel available in Egypt, thanks to having to fight the Soviets (and possibly Persian and Iraqi anti-British forces) in Middle East... and the active front in Scandinavia.

Last edited:

Chapter 19 - A Northern Affair

I wrote this chapter before I wrote Chapter 18 up, that's why this one's out so soon after the last one.

Chapter 19 – A Northern Affair

Scandinavian Campaign (Part 6)

May – June 1940

Since Operation Silver was launched in March 1940, a state of war had existed between Sweden and the Anglo-French Allies, by now referred to as the “Lapland War”. As RAF bombing raids launched from Norwegian bases beginning to strike Sweden in targets such as Kiruna and Luleå, the Swedes had accepted German offers of military aid and the Luftwaffe began to deploy to Swedish airfields. Nonetheless, this was a war that no one had wanted. The British wanted to be able to walk across Lapland to reach and aid Finland in the Winter War and naively expected the Swedes to acquiesce, whilst the Swedes for their part just wanted to be left alone by everyone and stay out of the war entirely. As it turned out though, the British invasion of the north of Sweden and air raids had forced the situation into all-out war, a situation both sides found almost impossible to pull out of.

However, an attempt to do such was made in early June 1940. On 5th June, after the evacuation of British troops from Dunkirk, the British government reached out to Stockholm through their embassy in neutral Finland offering to negotiate an end to the Lapland War.

When the offer of negotiations reached Prime Minister Hansson, he was unsure of how to react. His inner democrat jumped at the offer, detesting the alliance of convenience with the Nazis. But his inner realist was also aware that Sweden couldn’t afford to antagonise Berlin lest they decide to attack Sweden. Even if the Germans didn’t attack, a cutting of trade with Germany would be disastrous for the Swedish economy. When the cabinet was called that evening to discuss the British offer, it was decided that the offer would be taken up but in secret to avoid raising German suspicions given their prior agreements [1].

To maintain secrecy, contact with the British would be initiated through unofficial mediums, namely Sweden’s former ambassador to the League of Nations, Karl Ivan Westman. Westman also happened to be the brother of Justice Minister Karl Gustaf Westman. On the 7th, Westman met discreetly with Britain’s ambassador to Finland, Sir Gordon Vereker, and informed him that the Swedish government would be willing to negotiate, but the matter had to be kept secret. It was arranged that negotiations would take place in the city of Kornsjø, near the Swedish-Norwegian border. The first meeting was set to take place on the 10th, just as the Italians declared war on France and the United Kingdom.

The delegations met in Kornsjø at 11:00 with the 3-man British delegation headed by Sir Alexander Cadogan, the Permanent-Under Secretary of State, and also included Vereker and Harold Balfour, the Under-Secretary of State for Air. Representing France was Robert Coulondre, former French ambassador to Germany prior to September 1939. Representing the Swedes were Westman, Erik Boheman, the State Secretary for Foreign Affairs, and Björn Prytz, Sweden’s former envoy to the United Kingdom prior to the March invasion.

Sir Alexander Cadogan, Permanent Under-Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs

Harold Balfour, Under-Secretary of State for Air

Karl Ivan Westman, Swedish diplomat and namesake of the “Westman Affair”

Erik Bohemann, Swedish State Secretary for Foreign Affairs

The Swedish delegation made the first proposal. They requested an immediate end to military hostilities, a return to the status-quo antebellum, the ability to trade freely through the ice-free port of Narvik and financial reparations to pay for damages caused by the invasion and bombing raids.

The Anglo-French responded by stating that they wouldn’t allow Iron Ore or any other “war-making material” to leave through Narvik unless the Swedish government confirmed it wouldn’t be going to either Germany or the Soviet Union. Their logic for this was that if they returned to the status-quo antebellum, Sweden’s new neutrality would be pro-Axis as a legacy of the invasion. The Allies also demanded a withdrawal of all German troops from Swedish territory and a severing of all Swedish trade with both Germany and the Soviets. In return for complying with their conditions, the Brits offered to buy Swedish Ore instead and to protect Sweden in the event of any German or Soviet attack.

The Swedes were wary about accepting all of Britain’s conditions. Accepting the trade terms would effectively make Sweden a British economic puppet, assuming the Germans would accept Stockholm’s return to neutrality. Secondly, the Swedish delegation and government back in Stockholm didn’t view Britain’s promise to defend Sweden as worth anything, given their prior promises to Poland and failures on the Western Front [2].

That evening, Prime Minister Hansson received a telegram from Kornsjø notifying him that negotiations had failed to reach an agreement and would continue tomorrow.

The next day came and still negotiations fell through, around the issue of the Iron Ore trade with the British and French demanding Sweden cease shipments to Germany and the Swedes refusing to agree. Unfortunately, the issue of negotiations was going to be solved, just not how anyone wanted it to.

As the sun rose on the morning of the 12th of June, horror and confusion struck the faces of the Swedish government as the radical right-wing newspaper Vägen Framåt’s [3] front page read with “Sellout to the British Invaders!” and went into further detail regarding the talks in Kornsjø. And just to rub it in, they’d somehow managed to take a picture of Westman and Cadogan shaking hands outside the train station in Kornsjø where the talks were taking place. It turns out that one of the workers at the station, known to the Germans have had some pro-Nazi sympathies, had been compromised by the Abwehr. Now effectively working for German intelligence, the station worker had collected numerous intelligence pieces for his Abwehr masters, including the infamous photo; giving the talks and surrounding crisis its name, the “Westman Affair.” The perpetrator himself would not be discovered until his death in 2005 when his diaries were discovered by his grandson, causing a minor diplomatic incident and a scandal inside Sweden.

But right now, everyone in the government was panicking tremendously. Who had leaked the talks to the press? Was it German intelligence? Did the German government know? Did Göring know? Would the Germans attack Sweden in retaliation? What was to happen to Sweden? Its democracy? Its people? Was it all going to end? Some of these questions were of course catastrophising, but in the context of events in early-to-mid June 1940, the panic was understandable.

As it turned out, the Germans had been aware of the talks the whole time; at the same time as Prime Minister Hansson and his cabinet were digesting the news of the leaks, the Swedish envoy in Berlin, Arvid Richert, was receiving a berating from Göring and Ribbentrop for alleged “betrayal of prior agreements” and threatened that unless talks were stopped immediately, the consequences for Sweden would be severe. Richet was then released by his interrogators back the Swedish embassy to relay his “talks” with the German government back to his home country. At the same time, Richert advised in a separate telegram that it would be the best thing for Sweden if the talks were dropped and German demands accepted, believing Sweden still lacked the military strength to fight off a German attack, especially since there were now German forces inside Swedish territory.

Arvid Richert, Swedish Envoy to Germany

Simultaneously, the German ambassador in Stockholm, Viktor zu Wied, delivered an ultimatum to Hansson; end the talks with the Allies immediately and refrain from further hinderances to “the common resistance to unwarranted British aggression” or there would be “severe consequences for the Swedish nation and the Swedish people.” Hansson couldn’t believe what the world had come to. He hated the fact that Sweden had been dragged into this war, he hated whoever had leaked the talks to the papers and he despised this ultimatum in his hand. He wanted to reject it and proceed regardless, his inner democrat despising the idea of further collaboration with the Nazis (and by extension, the Soviets). However, he also feared what the Germans meant by “severe consequences,” especially with the German army blitzing its way through France. Could they do the same to Sweden?

Viktor zu Wied, Swedish Ambassador to Germany (picture c. 1900)

He figured he could only summon an emergency cabinet meeting to resolve the matter. Foreign Minister Günther was pessimistic, believing Germany’s military might (especially aerial) to be far superior to that of Sweden’s, having also read Richert’s correspondence which stated something similar. Defence Minister Skold was cautious, arguing that Sweden needed more time to build up its forces, and needed to continue weapons imports from Germany to do this. Justice Minister Karl Gustaf Westman stayed silent, knowing that his brother’s role in the talks essentially meant his career was over now.

Karl Gustaf Westman, Swedish Minister of Justice

Also during this time, King Gustaf V stepped in. The King, although no admirer of Nazism, desired to avoid conflict with Germany, with some sources going as far as to say he threatened to abdicate if the German demands were not accepted [4].

Gustaf V, King of Sweden

By the in the evening of that day, a decision had been made. Surrounded by chaos and with most of those around him pessimistic about Sweden's defensive capabilities against the Germans, Hansson went against his own better instincts and notified the German government through Richert that their demands would be accepted, and the talks would cease. With that single decision, Sweden had effectively surrendered itself to German influence and was now beholden to events increasingly outside its control.

The end of the “Westman Affair” did not mean the end of Prime Minister Hansson, but Justice Minister Westman was right about his career being over. On the 14th, he resigned to be replaced by Thorwald Bergquist, Westman's predecessor who had served in that office in 1936 in Hansson's first government [5]. The crisis was over, but its impacts on the war had been monumental.

Thorwald Bergquist, new Minister for Justice of Sweden

Footnotes

- [1] Referring to TTLs “Hansson-Ribbentrop Agreement” in Chapter 13.

- [2] Given that they’re negotiating behind Berlin’s back, the Swedes are in a risky enough situation as it is. Stockholm is understandably sceptical of Britain’s ability to uphold any promise to defend them given the ongoing debacle in France going on at the same time. Convincing Berlin that returning to neutrality doesn’t mean switching sides would be very difficult, if even impossible.

- [3] The newspaper associated with the fascist “New Swedish Movement” that ran from 1932 to 1992 in OTL.

- [4] A similar controversy surrounding King Gustaf existed in OTL during the Midsummer crisis of 1941.

- [5] In OTL, Bergquist was brought back to serve as Justice Minister from 1943 after Westman's resignation.

Sources

Wikipedia

List of newspapers in Sweden - Wikipedia

Swedish Wikipedia

Arvid Richert - Wikipedia

Comments?

Chapter 19 – A Northern Affair

Scandinavian Campaign (Part 6)

May – June 1940

Since Operation Silver was launched in March 1940, a state of war had existed between Sweden and the Anglo-French Allies, by now referred to as the “Lapland War”. As RAF bombing raids launched from Norwegian bases beginning to strike Sweden in targets such as Kiruna and Luleå, the Swedes had accepted German offers of military aid and the Luftwaffe began to deploy to Swedish airfields. Nonetheless, this was a war that no one had wanted. The British wanted to be able to walk across Lapland to reach and aid Finland in the Winter War and naively expected the Swedes to acquiesce, whilst the Swedes for their part just wanted to be left alone by everyone and stay out of the war entirely. As it turned out though, the British invasion of the north of Sweden and air raids had forced the situation into all-out war, a situation both sides found almost impossible to pull out of.

However, an attempt to do such was made in early June 1940. On 5th June, after the evacuation of British troops from Dunkirk, the British government reached out to Stockholm through their embassy in neutral Finland offering to negotiate an end to the Lapland War.

When the offer of negotiations reached Prime Minister Hansson, he was unsure of how to react. His inner democrat jumped at the offer, detesting the alliance of convenience with the Nazis. But his inner realist was also aware that Sweden couldn’t afford to antagonise Berlin lest they decide to attack Sweden. Even if the Germans didn’t attack, a cutting of trade with Germany would be disastrous for the Swedish economy. When the cabinet was called that evening to discuss the British offer, it was decided that the offer would be taken up but in secret to avoid raising German suspicions given their prior agreements [1].

To maintain secrecy, contact with the British would be initiated through unofficial mediums, namely Sweden’s former ambassador to the League of Nations, Karl Ivan Westman. Westman also happened to be the brother of Justice Minister Karl Gustaf Westman. On the 7th, Westman met discreetly with Britain’s ambassador to Finland, Sir Gordon Vereker, and informed him that the Swedish government would be willing to negotiate, but the matter had to be kept secret. It was arranged that negotiations would take place in the city of Kornsjø, near the Swedish-Norwegian border. The first meeting was set to take place on the 10th, just as the Italians declared war on France and the United Kingdom.

The delegations met in Kornsjø at 11:00 with the 3-man British delegation headed by Sir Alexander Cadogan, the Permanent-Under Secretary of State, and also included Vereker and Harold Balfour, the Under-Secretary of State for Air. Representing France was Robert Coulondre, former French ambassador to Germany prior to September 1939. Representing the Swedes were Westman, Erik Boheman, the State Secretary for Foreign Affairs, and Björn Prytz, Sweden’s former envoy to the United Kingdom prior to the March invasion.

Sir Alexander Cadogan, Permanent Under-Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs

Harold Balfour, Under-Secretary of State for Air

Karl Ivan Westman, Swedish diplomat and namesake of the “Westman Affair”

Erik Bohemann, Swedish State Secretary for Foreign Affairs

The Swedish delegation made the first proposal. They requested an immediate end to military hostilities, a return to the status-quo antebellum, the ability to trade freely through the ice-free port of Narvik and financial reparations to pay for damages caused by the invasion and bombing raids.

The Anglo-French responded by stating that they wouldn’t allow Iron Ore or any other “war-making material” to leave through Narvik unless the Swedish government confirmed it wouldn’t be going to either Germany or the Soviet Union. Their logic for this was that if they returned to the status-quo antebellum, Sweden’s new neutrality would be pro-Axis as a legacy of the invasion. The Allies also demanded a withdrawal of all German troops from Swedish territory and a severing of all Swedish trade with both Germany and the Soviets. In return for complying with their conditions, the Brits offered to buy Swedish Ore instead and to protect Sweden in the event of any German or Soviet attack.

The Swedes were wary about accepting all of Britain’s conditions. Accepting the trade terms would effectively make Sweden a British economic puppet, assuming the Germans would accept Stockholm’s return to neutrality. Secondly, the Swedish delegation and government back in Stockholm didn’t view Britain’s promise to defend Sweden as worth anything, given their prior promises to Poland and failures on the Western Front [2].

That evening, Prime Minister Hansson received a telegram from Kornsjø notifying him that negotiations had failed to reach an agreement and would continue tomorrow.

The next day came and still negotiations fell through, around the issue of the Iron Ore trade with the British and French demanding Sweden cease shipments to Germany and the Swedes refusing to agree. Unfortunately, the issue of negotiations was going to be solved, just not how anyone wanted it to.

As the sun rose on the morning of the 12th of June, horror and confusion struck the faces of the Swedish government as the radical right-wing newspaper Vägen Framåt’s [3] front page read with “Sellout to the British Invaders!” and went into further detail regarding the talks in Kornsjø. And just to rub it in, they’d somehow managed to take a picture of Westman and Cadogan shaking hands outside the train station in Kornsjø where the talks were taking place. It turns out that one of the workers at the station, known to the Germans have had some pro-Nazi sympathies, had been compromised by the Abwehr. Now effectively working for German intelligence, the station worker had collected numerous intelligence pieces for his Abwehr masters, including the infamous photo; giving the talks and surrounding crisis its name, the “Westman Affair.” The perpetrator himself would not be discovered until his death in 2005 when his diaries were discovered by his grandson, causing a minor diplomatic incident and a scandal inside Sweden.

But right now, everyone in the government was panicking tremendously. Who had leaked the talks to the press? Was it German intelligence? Did the German government know? Did Göring know? Would the Germans attack Sweden in retaliation? What was to happen to Sweden? Its democracy? Its people? Was it all going to end? Some of these questions were of course catastrophising, but in the context of events in early-to-mid June 1940, the panic was understandable.

As it turned out, the Germans had been aware of the talks the whole time; at the same time as Prime Minister Hansson and his cabinet were digesting the news of the leaks, the Swedish envoy in Berlin, Arvid Richert, was receiving a berating from Göring and Ribbentrop for alleged “betrayal of prior agreements” and threatened that unless talks were stopped immediately, the consequences for Sweden would be severe. Richet was then released by his interrogators back the Swedish embassy to relay his “talks” with the German government back to his home country. At the same time, Richert advised in a separate telegram that it would be the best thing for Sweden if the talks were dropped and German demands accepted, believing Sweden still lacked the military strength to fight off a German attack, especially since there were now German forces inside Swedish territory.

Arvid Richert, Swedish Envoy to Germany

Simultaneously, the German ambassador in Stockholm, Viktor zu Wied, delivered an ultimatum to Hansson; end the talks with the Allies immediately and refrain from further hinderances to “the common resistance to unwarranted British aggression” or there would be “severe consequences for the Swedish nation and the Swedish people.” Hansson couldn’t believe what the world had come to. He hated the fact that Sweden had been dragged into this war, he hated whoever had leaked the talks to the papers and he despised this ultimatum in his hand. He wanted to reject it and proceed regardless, his inner democrat despising the idea of further collaboration with the Nazis (and by extension, the Soviets). However, he also feared what the Germans meant by “severe consequences,” especially with the German army blitzing its way through France. Could they do the same to Sweden?

Viktor zu Wied, Swedish Ambassador to Germany (picture c. 1900)

He figured he could only summon an emergency cabinet meeting to resolve the matter. Foreign Minister Günther was pessimistic, believing Germany’s military might (especially aerial) to be far superior to that of Sweden’s, having also read Richert’s correspondence which stated something similar. Defence Minister Skold was cautious, arguing that Sweden needed more time to build up its forces, and needed to continue weapons imports from Germany to do this. Justice Minister Karl Gustaf Westman stayed silent, knowing that his brother’s role in the talks essentially meant his career was over now.

Karl Gustaf Westman, Swedish Minister of Justice

Also during this time, King Gustaf V stepped in. The King, although no admirer of Nazism, desired to avoid conflict with Germany, with some sources going as far as to say he threatened to abdicate if the German demands were not accepted [4].

Gustaf V, King of Sweden

By the in the evening of that day, a decision had been made. Surrounded by chaos and with most of those around him pessimistic about Sweden's defensive capabilities against the Germans, Hansson went against his own better instincts and notified the German government through Richert that their demands would be accepted, and the talks would cease. With that single decision, Sweden had effectively surrendered itself to German influence and was now beholden to events increasingly outside its control.

The end of the “Westman Affair” did not mean the end of Prime Minister Hansson, but Justice Minister Westman was right about his career being over. On the 14th, he resigned to be replaced by Thorwald Bergquist, Westman's predecessor who had served in that office in 1936 in Hansson's first government [5]. The crisis was over, but its impacts on the war had been monumental.

Thorwald Bergquist, new Minister for Justice of Sweden

Footnotes

- [1] Referring to TTLs “Hansson-Ribbentrop Agreement” in Chapter 13.

- [2] Given that they’re negotiating behind Berlin’s back, the Swedes are in a risky enough situation as it is. Stockholm is understandably sceptical of Britain’s ability to uphold any promise to defend them given the ongoing debacle in France going on at the same time. Convincing Berlin that returning to neutrality doesn’t mean switching sides would be very difficult, if even impossible.

- [3] The newspaper associated with the fascist “New Swedish Movement” that ran from 1932 to 1992 in OTL.

- [4] A similar controversy surrounding King Gustaf existed in OTL during the Midsummer crisis of 1941.

- [5] In OTL, Bergquist was brought back to serve as Justice Minister from 1943 after Westman's resignation.

Sources

Wikipedia

List of newspapers in Sweden - Wikipedia

Swedish Wikipedia

Arvid Richert - Wikipedia

Comments?

Last edited:

Threadmarks

View all 43 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

INTERMISSION: Per Albin Hansson’s speech regarding war with Britain and France Chapter 26 – The Beast from The East Chapter 27 – Stalemate in the Sky Map of Europe, 1 September 1940 ANNOUNCEMENT LOOK INTO THE FUTURE (3) Chapter 28 – The Alliance (Part 1) Chapter 29 – Hunting High and Low

Share: