In 1861, the Northern states of the Union had gone to war with the primary aim of upholding the unity and authority of their country, by compelling the rebellious states into returning. To say so is not to deny the simple fact that the Civil War was over slavery, for without it there wouldn’t have been secession and thus there wouldn’t have been a war. Republicans and abolitionists saw in the war an opportunity to weaken slavery, of course, and believed that after victory was achieved, they could enact their program with even greater vigor. But few could foresee the revolutionary changes the war would bring. The conflict that was supposed to last 90 days and restore the Union as it was, had been transformed into a crusade that sought to destroy and reconstruct the old South. As in other great struggles, the initial limited aims and scope had given way to a complete transformation of American society, that neither abolitionists nor fire-eaters could have predicted. The tide continued and gained greater strength in 1864, resulting in profound political, economic, and social changes, but also arising fierce resistance on the part of defiant rebels and reactionary Northerners, testing both the resolve and ability of the Lincoln administration to continue the Second American Revolution.

Nowhere else were the dramatic consequences of the war more evident than in the evolution of race relations in the occupied South, for in there the process of emancipation and then of land redistribution had completely overturned the traditional order of things. What was inconceivable just a few years prior, such as Black landownership or suffrage, had now become a tangible reality. The chief aims of the freedmen were the safety of their families; independence from White coercion; the right to manage their community affairs such as education and religion on their own terms; and just compensation for their labor or the obtention land. While it is true that slavery had robbed them of the chance to obtain education and literacy, and as a result many of the freedmen remained ignorant of formal political procedures and issues, the freedmen had firm ideas and convictions regarding their futures and strived mightily against powerful resistance to turn these dreams into reality. This struggle was inevitably political in nature. In offering a different vision of the future compared with that of loyal planters and Northern moderates, Black people, feared as “the Jacobins of the country”, became the essential basis upon which the Second Revolution was being constructed.

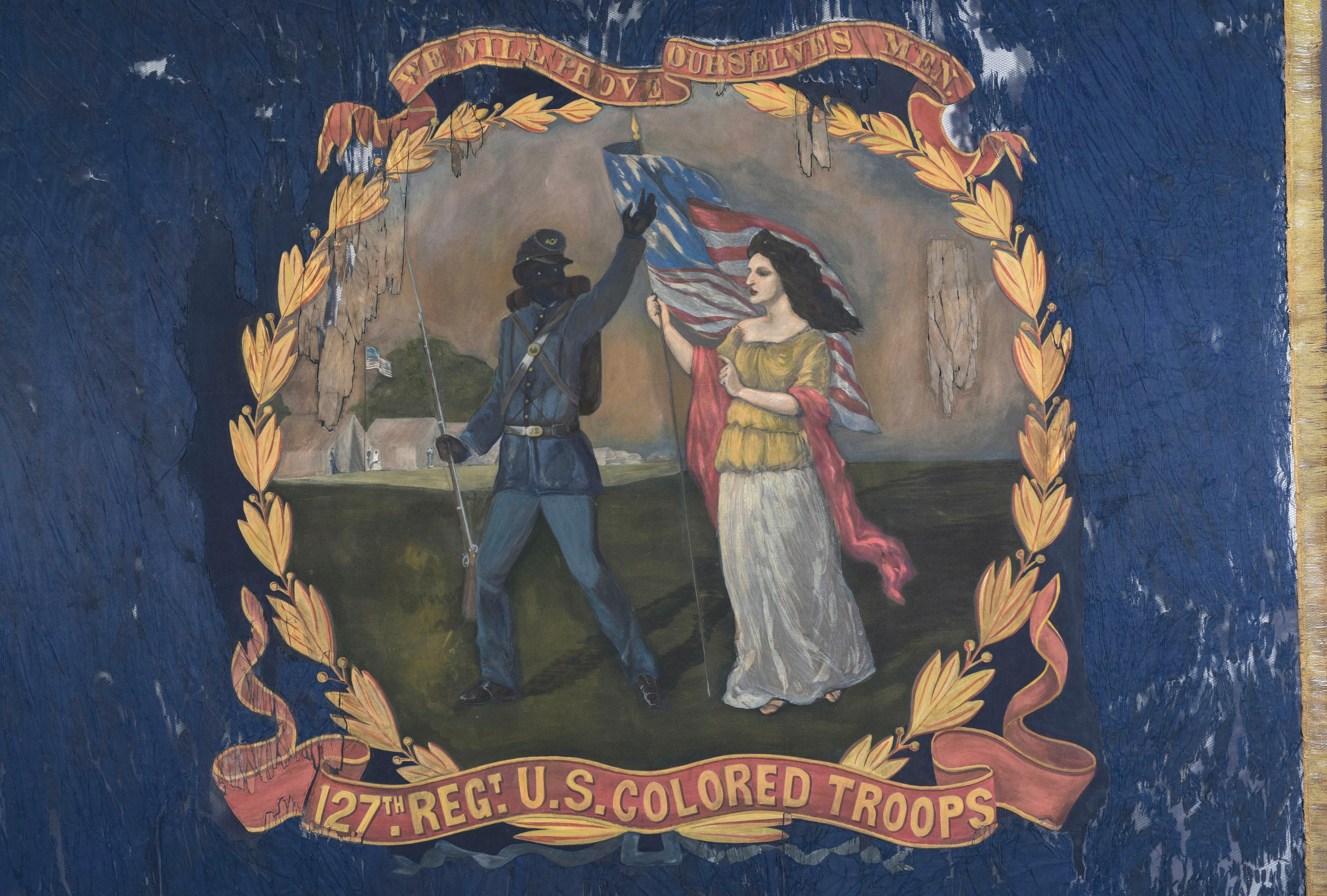

Emancipation, alongside from freeing Black people from bondage, allowed them to form a new political consciousness. As historian Eric Foner observes, “military service has often been a politicizing and radicalizing experience”, imbuing Black people with a dignity they had been previously denied. “No negro who has ever been a soldier,” wrote a Union officer, “can again be imposed upon; they have learnt what it is to be free and they will infuse their feelings into others.” Black communities thus started to justify their claims to freedom and political equality in the essential contributions of Black troops to the war effort and the glorious victories of their men over the rebels, such as in the Battle of Union Mills. In 1863, Thomas Wentworth Higginson heard an address delivered by the Black corporal Prince Lambkin, making the point that Black men who fought for the Union deserved better than the White men who fought against it. The planters had lived contently under the American flag when they were free to exploit Black people for their own benefit, Lambkin exclaimed, but “the first minute they think that old flag mean freedom for we colored people, they pull it right down and run up the rag of their own. But we'll never desert the old flag, boys, never; we have lived under it for eighteen hundred sixty-three years, and we'll die for it now.”

Countless such addresses and appeals were made reiterating the same point: Black people deserved to be considered as fellow Americans deserving of equal rights, because they had come forward to save the Union in its hour of greatest peril. This firm conviction resulted in increasingly militant demands on the part of Black communities, that the Federal authorities had hardly expected. The greatest demand was, of course, for the continuance and expansion of the policy of land redistribution. Originally envisioned as a limited measure meant to punish the Confederate leaders, coax wavering rebels into resuming their loyalty, and deal with the humanitarian crisis, land redistribution was similarly to emancipation not meant to effectuate a revolution. But with the floodgates open, there was no turning back, and throughout 1864 the commitment of the Union to land reform increased, exemplified in several orders that set aside large expansions of land for the settlement of freedmen and loyal Whites. As a Northern scholar observed, the Federal government could not stop the “revolution in land titles” in the South any more than the French National Assembly was able to moderate the abolition of feudalism “during their own revolution”. The reason was the same: “the rural peasantry, theirs White, ours Black, but similar in their Jacobinism”.

Black Union soldiers were essential in the development of a new consciousness and self-conception within Black Americans

Throughout the South, freedmen fought to obtain lands on which to live and work, uniting to obtain concessions or leases, seizing plantations on their own initiative, and clinging mightily to land whenever they managed to take it. “The chief object of ambition among the refugees," a Freedman’s Bureau report declared in 1864, “is to own property, especially to possess land, if it be only a few acres”. Black people and their radical allies justified the freedmen’s claim to land on the fact that they had already been “bought and paid for by their sweat and blood”. But the primary argument they wielded was not an appeal to justice, but rather stating that land redistribution was sound policy because it both punished the rebels and allowed the freedmen to take care of themselves. Otherwise, constant Federal intervention would be needed to protect the freedmen. As a Black man said: “Gib us our own land, and we take care of ourselves; but widout land de ole massas can hire us or starve us, as dey please”. A Northern paper editorialized the same point in somewhat harsher terms: “The Negro is to swim or sink by his own efforts. Root, hog or die, we say!”

Nonetheless, most Federal authorities, including Lincoln and the majority of Bureau agents, maintained their belief that simply giving the land to the freedmen could be disastrous. It would teach them “idleness and unthrifty habits”, said Edward Philbrick, when they had to learn instead that “No race of men on God’s earth ever acquired the right to the soil on which they stand without more vigorous exertions than these people have made”. Freedmen bitterly argued that they already had the right to the land, to “dis bery land dat is rich wid de sweat ob we face and de blood ob we back.” But the Yankees remained steadfast in their belief that the freedmen had to prove their worth first, and thus instituted a system to “test whether they will indeed work on their own”. At the very least, Northerners were not acting hypocritically, for the process for obtaining land instituted by the Second Southern Homestead Act of 1864, worked on alongside the 13th amendment and passed just a few days prior, was remarkably similar to the provisions of the Homestead Act. Land would be given to the freedmen in a “provisionary” basis for the length of one year. If they had made improvements in the land and proved that they could farm it independently, they would be granted a secure title. Otherwise, the land would revert to the Federal government. The act further dictated that the freedmen could buy land at below-market prices, giving the Land Bureau the power to set prices, and that those who had leased land for at least a year would receive an immediate title.

The relatively small period of a year was owed to wartime needs, and in exchange the act capped the granting of such land to only 40 acres compared with the 160 acres contemplated in the Homestead Act. Any acre over that amount had to be either bought or leased by the freedmen at market prices. The most interesting part of the act was that it modified the way that land would be restored, in accordance with President Lincoln’s earlier Proclamation of Amnesty. Freedmen would be allowed to “pre-empt” land by seizing and cultivating it, with that time counting for the probatory year. Land thus preempted could not be restored to the former owner even if he swore a loyalty oath, nor could it be leased or purchased by Northern factors or even other loyal Southerners. Only if the freedman failed to prove his capacities would it be returned; otherwise, the recanting rebel would receive Union bonds for the current, most likely highly devalued, price of the land. The only exception was if the land had belonged to poor yeomen, who would have their land returned at once as long as they hadn’t owed over 500 dollars in property before the war and were not in the list of those who could not take the loyalty oath under Lincoln’s proclamation.

It must be remembered that the aforementioned list of exemptions included the great majority of civil officials and military officers of the Confederacy, the class of men who had owned the great majority of the South’s land. These men could not take the loyalty oath or have their lands restored. Consequently, land preempted by the freedmen was likely to belong to one of them, thus leaving the one-year probation as the only hurdle to a secure title. This was, fortunately, an easy enough obstacle to overcome, given that the Black former slaves had ample capability to cultivate the land on their own. It may bewilder modern readers, but the sad truth is that many Northerners honestly believed that Black people would not work on their own, despite the evident fact that they had been doing so for decades already. Questioning the capacity of the freedmen to farm their plots was an “outrage”, exclaimed vehemently Jean-Charles Houzeau. If anything, the ones who would starve if left on their own devices on the plantations were the planters themselves, Houzeau continued. They who “had always lived by the sweat and suffering of the colored man” and “had never known of toil”, were less fit, under the “theorems and doctrines of the North” to own the land.

Rather than reparations as such, land redistribution was meant to give an opportunity to Black people to prove their worthiness of being free men

To instruct the freedmen in the workings of free labor economies and assure that the home farms produced enough cotton for Northern needs, the Union government instituted a simultaneous system of incentives for the production of cotton. Freedmen who chose to cultivate the crop would receive tools, seed, and food provisions by the Union Army. As payment, the Federals would take up to 50% produced cotton, depending on the size of the home farm and the number of inhabitants. The rest the freedmen could sell, but the Federal government and the merchants it authorized had privilege. To prevent the freedmen from being exploited, the Labor Bureau had the power to fix prices, not only of the cotton they sold but of the merchant wares they might buy. Through this system the Federal government wanted to encourage the “enterprising colored farmers” to focus almost exclusively on the cultivation of cotton – for example, the fact that the Union would feed them would obviate the need for cultivating food themselves. The system came to be known as the “cotton-mule policy”, because the government would give the Black settlers a mule in exchange for their cotton. To further cement it, the Union allowed Northern factors to invest in the so-called “colored bonds”, which entailed covering the initial costs of the operation in exchange for a part of the government’s share at harvest time.

The new system allowed Black people to claim hundreds of acres of land, and by the start of the next year most of the initial farmers had obtained a secure title and started to build up wealth. But similarly to how the Homestead Act was unable to give “every poor man a farm”, the Second Southern Homestead Act could hardly grant land to every freedman. Especially, the nature and development of land redistribution as a policy meant that it was applied in an uneven fashion. By middle-1864, relatively few acres had been redistributed in Tennessee or Louisiana, both occupied before the policy had been developed, while a significant portion of Mississippi was already in the hands of freedmen and most of Alabama had been preempted by the enslaved who seized plantations during Sherman’s and McPherson’s marches. Even in areas where the program had seen more success, many estates had remained in the hands of White planters who had been quick to pledge loyalty to the Union. There, many freedmen still had to work for White employers. But even there an evident shift in favor of the freemen could be observed throughout 1864.

On May 13th, 1864, the anniversary of the Battle of Union Mills, Lincoln issued the Proclamation of Loyalties, an addendum to his earlier proclamation. This marked the transition from a standard of “passive loyalty”, to one of “active loyalty”. This meant, in the words of John Hay, that the Union would demand “loyalty, not only of words, but of acts and spirit”. The proclamation repealed the aggravating vagrancy and curfew regulations, delimited rights for the freedmen, and prescribed punishments for anyone who violated them, especially if they had already taken the loyalty oath. The proclamation expanded the powers and domain of the Bureaus, critically even into the Border States, and declared that labor disputes had to be resolved and contracts had to be crafted collectively, before a three-man panel with a representative of the planters, one of the Bureau, and one of the freedmen. Even more shockingly to planters was that Lincoln allowed many freedmen to choose Black representatives. This proclamation, a Mississippian whined, was calculated to “make the negroes insolent and idle and protect them in their meanness,” by subjecting “loyal planters” to “the annoyance and disgrace of going before the Yankee commander to answer any negro's charge, and there to have no more dignity and respect than is shown the negro.”

The Proclamation thus had stripped planters of much of the coercive power they had once held over the freedmen, and now they had to feel the “debasement” of negotiating for terms of employment under the watchful eyes of the Bureau. For a class of men who had been used to holding all the levers of power, to find themselves disadvantaged was “mighty humiliating”. A Louisiana planter wailed of the “terror” that the Bureau “holds over our people—by listening to and sustaining the negro in evy frivolous and malicious complaint—[it] amounts to a practical denial of the rights of the white man.” The planters who refused to compromise would soon find that no one wanted to work for them. One testified that “the negroes would all rather starve together than work for someone they think is a bad master”. To get laborers, planters had to offer wage raises, pledge to build schools, and often agree to not try to direct or control their work. Whereas many planters had initially believed they could exploit the freedmen in a close approximation of slavery, now they found themselves “utterly ruined by our incapability to direct labor” now that they could not count on State-sponsored violence to impose their will. Moreover, with many Yankees actively sympathetic to the freedmen and their aspirations, former masters for the first time had to thread carefully, a sharp and sudden turn away from the complete power they had once enjoyed. It was a “society turned upside down”, in the words of one of them.

To be sure, in reality the Bureaus all had to contend with a restless planter class that, even if greatly weakened, could still put-up staunch resistance to this astounding social transformation. Especially in many rural areas where the reach of the Bureaus and the Army was limited, the freedmen were still victims of fraud and abuse. Planter’s associations formed “Black patroles” that traversed the countryside “whipping and otherwise male treating the Freedmen”, reported a Bureau agent. All these violent actions were meant to prevent the freedmen from accessing to land or appealing to the aid of the Bureaus. Far from successfully subverting the Federal authorities, such threats and acts only stiffened their resolve and led to greater enforcement on the part of the Army. Especially ominous for Southern Whites, both in the Union-occupied areas and the Confederacy, was the execution of a planter after he had been found organizing a “militia company”. Despite impassioned pleas to pardon him or commute the sentence, Lincoln had allowed the execution to take place, coldly stating that “men who call themselves loyal” should not be allowed to “raise a rebel army in our midst” with the purpose of “subverting the rights of the colored citizens”.

The Labor, Land, and Freedmen's Bureau all exemplified the great changes of the Revolution

The new vision for the Southern future would not have been possible without the Black freedmen who defied their former masters, sustained the Union, and pushed forward revolutionary changes in political, economic, and social life. If it is true that at the end of the day the Lincoln administration was the one with the final say over the policies of Black landownership, suffrage, and equal rights, it is also true that without the pressure and support of Black people Lincoln would have likely never adopted these policies. It was their “second front” within the Confederacy, of escaping to Union lines and resisting slavery, that had paved the path of emancipation; it was their resistance to the initial poor arrangements of labor and their struggle for land that inspired confiscation and redistribution as viable programs; it was their valor in the field of battle and their political mobilization that had created and mustered support in favor of limited Black suffrage and equality under the law. In middle-1864, even as the Union’s prospects grew dimmer and Lincoln more pessimistic of his presidential bid, freedmen continued their fight for a new nation, giving both essential support to the Lincoln administration, and pushing it into new realms.

That this militancy was here to stay was clear in the many events and parades that took place to commemorate the anniversary of the Battle of Union Mills and the 4th of July. In South Carolina, Thomas Wentworth Higginson observed a grand parade that featured a Black woman as the Goddess of Liberty and the spiritual “In That New Jerusalem”, which sounded like “the chocked voice of a race at last unloosed”. In Tennessee and Kentucky, local Whites held a meager celebration, while “The negroes . . . with flaunting banners . . . were prominent in the principal streets, had speeches, songs, religious observances, a plentiful and luxurious dinner, and cast their white brothers entirely in the shade.” In New York, where a year earlier the Black residents were “literally hunted down like beasts”, a USCT regiment marched through the city before a “large, appreciative crowd to Union Square”. In Philadelphia, the Heroes of Union Mills were celebrated during the Republican Convention, with one regiment making part of Lincoln’s personal guard. All these were signs of the “dissolving prejudices against the colored men”, observed a newspaper. But more importantly, they were signs of the new relationship between the American nation and its Black citizens. The Reconstruction of the Union, W.E.B. Dubois analyzed years later, began with “the reconstruction of the slave into the man; of the chattel into the citizen”. Through their efforts and rhetoric, Black people had turned the Civil War into a true revolution, creating new conceptions of the political world and their place within it that were all but impossible to imagine in the antebellum.

But this vision for a new nation was not one shared by all Americans, and like any other, the Second American Revolution arose strong opposition from those sectors that wished to maintain the status quo. The moves of the Lincoln administration towards this new program of Reconstruction, with its frightening confiscation and Black rights, resulted in the growth of movements that can only be called counterrevolutionary. Instead of a new South, they envisioned a revival of the old one, perhaps with slavery intact or at the very least Black people still subjugated by the authority of supposedly loyal planters. Certainly, in their vision there was no room for Federal enforcement of Black rights, for most refused to even recognize that Black people had rights that White people were bound to respect. If Republicans more and more came to believe that Black people were citizens worthy of respect and protections, these reactionaries retained their devotion to White Supremacy, and interpreted all national efforts at protection as vindictive, cruel oppression against Whites. During the summer of 1864, they redoubled their opposition to the Lincoln government and its aims, which in turn inspired further repression and solidified the idea that loyalty to the Union meant a commitment to the ideals of liberty and equality.

In March 1864, and then later in June, Lincoln had been obligated to issue a new draft order in order to replace the men who hadn’t reenlisted and those lost in the spring and summer campaigns. In order to enforce it, Lincoln once again suspended the writ of habeas corpus, and ordered Army units into those districts that had seen “disturbances” during the last draft calls. This turned out to be a good call, for several agents were murdered and riots were started in response to this “attempt to make us fight for niggers”, as an Ohioan denounced openly. Reflecting increasing politicization, the Union Leagues helped in the work of conscription by attacking and humiliating those who wanted to shirk their duties. In response, it could be observed that those who opposed the government were also organizing. In a situation remarkably similar to the one in the Confederacy, many draft dodgers united in armed bands that repelled Federal agents, defied the government, and “created their own little confederacies in the free states”, according to colonel. In especially critical areas, “John Breckinridge had more authority than President Lincoln”, according to a report, for these were “rebels, proud and defiant”.

The draft remained extremely unpopular, especially among the poor

There was some exaggeration in these reports, but it is indisputably true that many of these Copperheads were cooperating with rebel agents, just as they had done in previous occasions. But no insurrection materialized, mainly because as James McPherson notes the rebel agents “were trying to prod

peace Chesnuts into

war against their own government.” Nonetheless, resistance was so stout that Lincoln was forced to employ extreme means, authorizing the arrest of anyone who did as little as “speaking ill of the draft”, and exiling to the Confederacy three judges who had issued writs of habeas corpus in plain subversion of his order. In a rare moment of bitter anger, Lincoln issued a public letter rallying against those “men who believe that their success can be found in the ruin of the government”, and thus “labored day and night to assure our failure and the destruction of our nation”. Lincoln expressed his astonishment at the resistance to those measures he believed necessary to save the Union. “Wherein is the peculiar hardship now?”, he asked in increasing disgust. “Shall we shrink from the necessary means to maintain our free government, which our grand-fathers employed to establish it, and our own fathers have already employed once to maintain it? Are we degenerate? Has the manhood of our race run out?”

These events and words, David H. Donald comments, “illustrated the determination, amounting almost to ferocity, with which Lincoln was prosecuting the war”. The Revolution in American politics that was sweeping the South also arrived at the North, steadily weakening the old prejudices, and opening new visions for the future. The once unthinkably radical project of a country of equality enforced by a powerful National State seemed now an inexorable reality. George S. Boutwell was right when he observed that the war had made it necessary to create a “new government”, for this new American State, with its standing armies, enlarged bureaucracy, expanded courts, and powerful national government scarcely resembled its antebellum counterpart. The policy of the country, said Senator John Sherman, “ought to be to make everything national as far as possible; to nationalize our country so that we shall love our country.” In line with this radical change of the conception of the American nation and its duties to its citizens, the Congress had passed a third measure alongside the Homestead Act and the 13th amendment: the Rebellion and Loyalties Act, which established a national police force for the United States.

Building on the foundation laid by the Third Confiscation Act, the new law expedited the first national Penal Code in American history, which was, naturally, almost entirely focused on wartime issues. For example, it regulated the punishments for those who were found working with the enemy, evaded the draft, or raised in rebellion against the government. It prescribed punishments such as confiscation, disenfranchisement, and imprisonment; again, making it clear that it was punishing rebellion and not treason. It reformed the ad hoc system of military courts in favor of a greatly expanded Federal judiciary, which was now empowered to hear cases regarding the “denial of the rights of American citizens”, including refusing to acknowledge the freedom of emancipated slaves, not respecting the proprietors of redistributed land, or intimidating or attacking Black voters. It further declared that all three Bureaus would operate for three years after the end of the war, assigning them their own budget, and permitted the establishment of offices and agents in any territory that had had slavery in 1861, not just in the rebel states. Finally, it swept away the National Guard as it had existed before the war. Loyal states could establish Civil Guards under tighter Federal oversight, but the rebel states could not unless they received the approval of Congress. The name National Guard was instead given to a gendarmerie, which had the power to enforce laws in any part of the United States. To aid it, a national police force known as the U.S. Constabularies, under the direction of the U.S. Marshals, was also established.

This unprecedented step was taken mostly in reaction to the predominant belief that there remained thousands of Copperheads ready to try and overthrow the Union. The Union Army, especially following in the Month of Blood, had tried to take in more and more police duties, establishing military tribunals and trying to uproot possible conspirations. But its work was found lacking, and as rumors of insurrections mounted, and especially following the attempt on Lincoln’s life, it was decided that a more constant, prepared force was necessary to enforce Federal laws and maintain the integrity and authority of the government. Ironically, one of the first most temperate measures had just contemplated a Presidential Guard that protected solely Lincoln and other government officials. But Lincoln demurred, expressing open dissatisfaction at this attempt to grant him a “praetorian guard”, and saying that the government should afford equal protection to all, not focus just on the President. Events in the Southern and Border States, where intimidation and violence of freedmen continued and defiance of the government was commonplace, also convinced lawmakers of the necessity to expand the jurisdiction of the Federal courts and the enforcement powers of the National government. “I admit,” said Maine Sen. Lot M. Morrill, “that this species of legislation is absolutely revolutionary. But are we not in the midst of a revolution?” In its massive expansion of National power, the Rebellion Act acted “as if the monstrous amendment was already part of the constitution”, commented a Chesnut. Republicans in this way were building a new nation, but also raising the stakes of the election and the war.

The willingness and capacity of the government to push the Revolution forward was tested in the Border State of Kentucky more than anywhere else. Despite the pressure of Philadelphia and the use of the Army to erode slavery by means of Black recruitment, Kentucky’s leaders clung stubbornly to slavery, doing “everything they could to thwart the Union antislavery policy”. The Kentucky Court of Appeals plainly declared the Emancipation Proclamation and all other such measures unconstitutional, insisting that the Federal government had no power to emancipate any slave. If it had such a power, the Justice reasoned, it would not have crafted the 13th amendment. As for the attempt to grant rights to the Black man, the Court insisted that he “remained under all his former political disabilities, and with no political rights except such as the various states might see proper to permit him to enjoy” – in other words, the Federal government had no power to “create imaginary rights” that Kentucky was bound to respect. Kentucky officers resisted the recruitment of Black slaves and refused to acknowledge that under American law the wives, mothers, and children of Black Union soldiers were to be freed too. When a Union general issued passes to the enslaved to leave their plantations, a Kentucky jury indicted him, whereupon the Army had the jury members and the judge all arrested. Kentucky, historian James Oakes says, “had become a national spectacle”.

Not even the guerrilla war, which in Missouri and Maryland had strengthened the anti-slavery faction, was capable of forcing an evolution of thought in Kentucky. In fact, many outlaws were former Union soldiers who deserted in the face of the Union’s increasing radicalization. Federal commanders who wished to use the methods of harsh war to deal with these guerrillas often found that the State officials were seemingly actively supporting them. The actions of General E.A. Paine were especially bitterly denounced as a “reign of terror . . . the most terrifying and horrible despotism.” Operating in seven pro-Confederate counties known as the Jackson Purchase, Paine employed brutal tactics to crush the guerrillas, starting a tragic series of reprisals and counter-reprisals. When James Kesterson, also known as “Captain Kess”, massacred thirty Unionists, Paine ordered an equal number of captured guerrillas shot and publicly executed the unrepentant Kesterson. In response, the guerrillas announced that “all the Union men, women and children would be shot in the district.” The bloody pledge was fulfilled with the massacre of over 100 men, women, and children through several raids, making Paine order the expulsion of all inhabitants of the Jackson Purchase, and the confiscation of all their properties. General Stephen G. Burbridge, denounced as the “Butcher of Kentucky”, employed similar methods, executing close to a hundred rebel prisoners after the Confederates massacred Black troops at the Battle of Saltville.

Instead of being chastised, Kentuckians redoubled their opposition. The most astounding show of the divisions was observed in August, when two Kentuckian regiments refused to serve unless both Paine and Burbridge were arrested and “hanged for their mercenary atrocities”. The Federal authorities immediately demanded their arrest, and when several Midwest regiments approached the Kentuckians fired upon them. The resulting battle between regiments that were all ostensibly on the same side made evident the deep, almost irreparable divisions between the two camps of Unionists. The news that the “abolition troops” were firing on Kentuckians, even if the Kentuckians had started the battle, in turn resulted in an riot in Louisville, which was bloodily put down. In the opinion of the fiery Joseph Holt, the current Republican candidate to Vice-President, Kentucky had through its refusal to submit to the authority of the Union government “practically seceded and joined the infernal rebellion”. A sweeping series of arrests and even executions followed the Louisville insurrection, with the Union Army practically overthrowing the State authorities. Several members of the Legislature were arrested, and the erstwhile Unionist and former governor James Robinson, together with the current Lieutenant Governor Richard Taylor Jacob, ended up fleeing to Confederate lines. This iron grip prevented a general insurrection or formal secession, but it resulted in a worsening of the guerrilla war that “threatens to completely depopulate the State”.

The fiasco in Kentucky was, for Copperheads and Chesnuts, the definitive proof that Lincoln was a tyrant without respect for constitutional rights, who would immediately abolish the States all to force “Whites to be the slaves of niggers”. They painted apocalyptic pictures of a future where the gendarmerie executed all “White men who did not grovel at the feet of the Negro” and the Army “confiscated fair daughters and wives for the benefit of those savages”. In reaction to the shifting Northern aptitudes, Chesnuts started an unabashedly racist campaign that sought to shore up White Supremacy and reverse the tide. The “flat-nosed, long-heeled, cursed of God and damned of men descendants of Africa”, did not deserve freedom or equality, they exclaimed. If the Northern people didn’t stop Lincoln’s “fanatical excesses” by voting against him, they could contemplate a future of “miscegenation”, that is, the “the blending of the white and the black.” Lincoln’s willingness to "make the White man suffer in benefit of the damn nigger", they said, was also obvious in his continual refuse to exchange prisoners of war, as long as the Confederates didn’t treat Black men as soldiers.

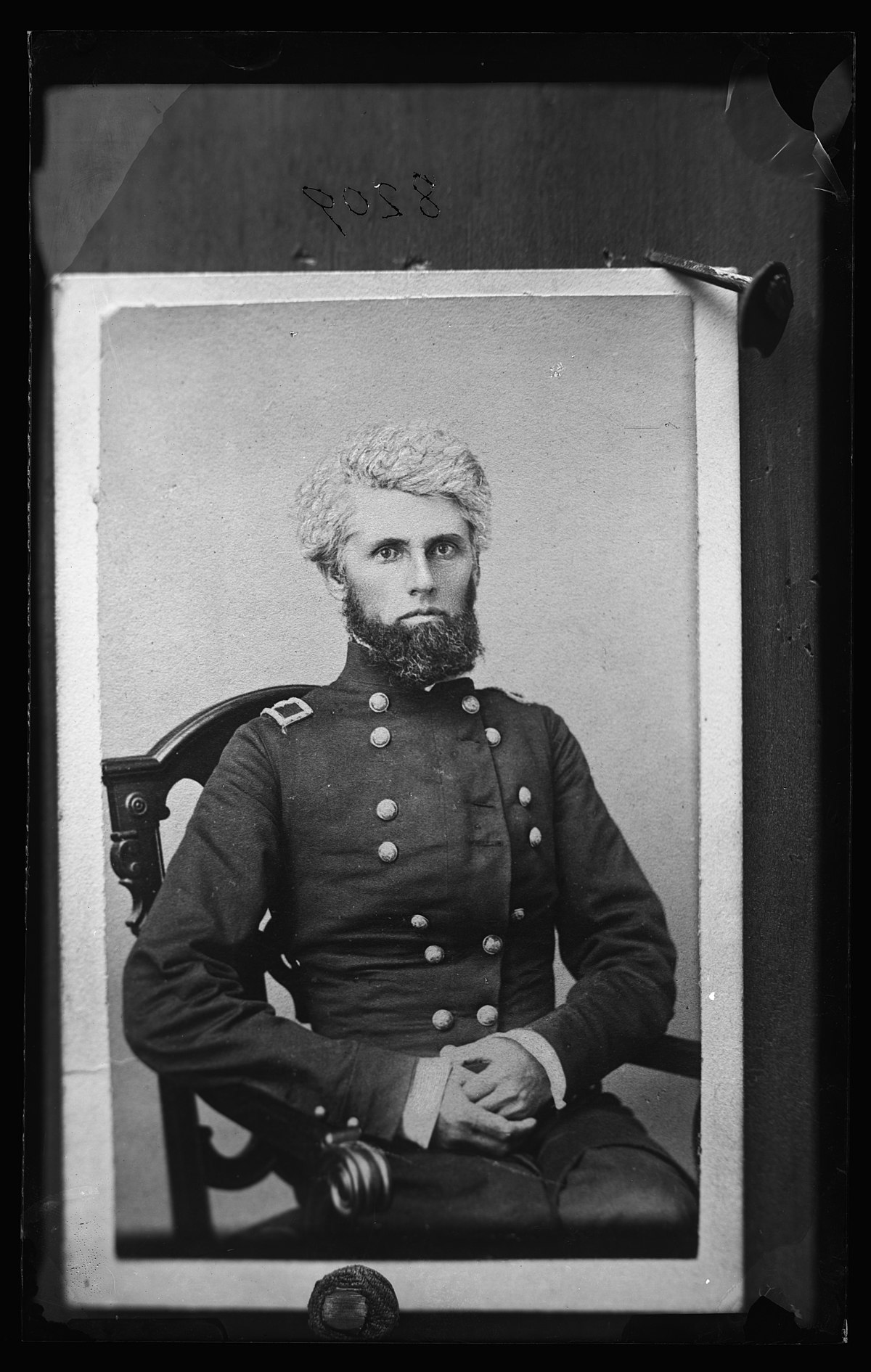

General Eleazer Arthur Paine

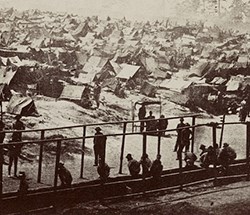

This issue was an especially sensitive one, because after the prisoner cartel had been broken over the Confederate refusal to treat Black soldiers as prisoners of war, the reports of cruelty against Union POWs had increased. The dreadful casualties of the 1864 campaigns had overcrowded the rebel prisons, increasing the pressure on Lincoln to abandon his policy and resume the exchange cartel. Garrett Davis, for example, thundered that “all the negroes in America should never have been one iota in the way of or an obstacle to the free and prompt deliverance of our unfortunate white soldiers in captivity.” Breckinridge added fuel to the fire by proposing to renew the cartel with the sole concession of treating Black soldiers who had been free at the time of enlistment as POWs. But Lincoln still refused, even as some Northerners grew desperate in their pleas to deliver the White prisoners from the “unspeakable conditions” of prisons such as Andersonville, where starvation, exposure, and disease were killing thousands of Union soldiers. A Republican warned that otherwise good Union men “will work and vote against the President, because they think sympathy with a few negroes, also captured, is the cause of a refusal”.

In Copperhead eyes, a similar undue sympathy for Black people was also the cause of Lincoln’s refusal to offer terms of peace. The failures in the summer of 1864, with their corresponding toll of hundreds of thousands of deaths, had made many Northerners willing to concede almost anything, maybe the Union itself, in exchange for a cessation of hostilities. During those months, many men worked to try and force Lincoln to arrange a peace settlement. Horace Greeley managed to prevail over Lincoln, getting him to accept an unofficial meeting with three Confederate agents in Niagara Falls, Canada. The agents, Greeley said, had “full authority to negotiate a peace”. Given that Breckinridge would not accept any peace terms that didn’t include independence, offering “generous terms” only to see them rejected would remove the “wide-spread conviction that the Government and its prominent supporters are not anxious for Peace.” Lincoln was wary of this plot, but if the Northern people believed that he was “flatly rejecting a reasonable peace negotiation, it could do irreparable damage”. But when Lincoln sent Greeley to Niagara Falls, he did so under strict instructions to negotiate for a proposition “embracing the restoration of the Union and abandonment of slavery.”

In truth the agents had no authority whatsoever to negotiate any peace terms, but Lincoln’s insistence on emancipation allowed them to put upon him “the odium of putting an end to all negotiation”. This time, a shrewd Breckinridge had outmaneuvered Lincoln, by portraying him as the only obstacle to a possible peace. Certainly, Breckinridge did not specify what terms would be acceptable to the Confederacy, but he willingly allowed Northerners to think that he might agree to re-union if emancipation was dropped as a precondition. This refusal had “sealed Lincoln’s fate in the coming Presidential campaign”, declared the

New York Herald. Lincoln did not wish to end the war “even if honorable peace were within his grasp”, denounced Chesnut leaders, because his true objective was to “exhaust our men and treasure for the benefit of the black race”. A dismayed Greeley scolded Lincoln for making it seem like the rebels are "anxious to negotiate, and that we repulse their advances.” An attempt at damage control by sending two Union agents to Richmond failed. Meeting with Breckinridge, the agents offered amnesty in exchange of abolition and reunion. The Machiavellian Breckinridge talked calmly but vaguely of a possible armistice and honorable terms – a proposal that would amount to Confederate victory, for “honorable terms” meant independence to them, but which at the same time held the tantalizing possibility of peace before weary Northerners.

"Tens of thousands of white men must yet bite the dust to allay the negro mania of the President” denounced a Chesnut editorial. Many who were willing to support Lincoln felt alienated, like a War Chesnut who said that Lincoln’s intransigence “puts the whole war question on a new basis, and takes us clear off our feet, leaving us no ground to stand upon.” Henry J. Raymond, the chairman of the Republican National Committee, grimly told Lincoln that “the tide is setting strongly against us”, due to “the want of military success, and the impression . . . that we can have peace with Union if we would . . . [but that you are] fighting not for Union but for the abolition of slavery.” Raymond urged to make a second offer with “the sole condition of acknowledging the supremacy of the constitution”. Lincoln, under enormous pressure, almost acquiesced. But then he pulled back, telling Raymond that offering such terms “would be worse than losing the Presidential contest—it would be ignominiously surrendering it in advance.” Despite all, Lincoln would not surrender his principles – he would only accept both Union

and Emancipation. However, in that moment of crisis, Lincoln could only feel pessimistic about his chances and the future of the Union. “I am going to be beaten,” he said to a friend, “and unless some great change takes place

badly beaten.”

It was in this context of military failure, pressure for peace, and increasing demoralization that the divided Chesnuts had organized conventions to try and select a candidate to beat Lincoln. In May, the tide seemed to be in Lincoln’s favor, and this resulted in fatal divisions within the National Union. The National Committee of the Party had originally set July 4th for a Convention in Chicago. But their unity almost immediately fractured when it was announced that Vallandigham planned to attend. The Peace faction further asked for the convention to be delayed, to observe the military situation. War Chesnuts plainly refused. They believed that if they allowed the Copperheads in the government or the Union Leagues would interfere, and given the expectations of success they didn’t wish to be painted with the brush of treason. In the scheduled date, the National Union met and nominated Andrew Johnson and William Franklin, both strongly conservative but also unimpeachably loyal, on a plank that called for unconditional victory but repudiated emancipation and land redistribution.

A couple weeks later, on July 25th, the national convention of the National American Party met in New York. This movement had been organized by Samuel J. Tilden and Thurlow Weed, professing to be finally the party that pursued both victory and moderate aims. Declaring the abolition of slavery “a fact accomplished”, Tilden proposed to simply ignore the question. Slavery’s abolition was, in fact,

not accomplished, but by leaving it aside instead of talking against emancipation like the National Unionists did, Tilden hoped to strike a more moderate tone that would attract Republicans unwilling to swallow either extreme Copperheadism. By dropping emancipation as a precondition, the great majority of the enslaved, who still hadn’t been freed by Union arms, would remain in slavery. The plank moreover contemplated “all honorable concessions” in the name of peace, including compensation for the slaves that had been freed, speedy restoration of the States, and “true universal amnesty”. For Tilden and his men, the key issue “must be condemnation and reversal of negro supremacy”, which entailed brushing aside Lincoln’s reconstruction policies, restoring the antebellum status quo as much as possible, and bounding the freedmen to serfdom. Tilden originally hoped Lincoln would adopt the plank, but when he refused, Tilden took charge and was nominated alongside Francis Preston Blair Jr. The movement would grow more racist and reactionary in the following months.

On August 15th, a third Chesnut convention met in Cincinnati. This was the Copperhead convention, chaired by peace men and with a plank drawn by Vallandigham. Lincoln had refused to do anything against it, because he believed that doing so would only strengthen their narrative of being martyrs of constitutional liberty. The platform focused on Lincoln’s supposed tyranny, condemning his “arbitrary military arrests” and “suppression of freedom of speech and of the press”, while calling for preserving “the rights of the States unimpaired” – that is, conserving slavery. Though the Party nominated George Pendleton and Thomas Seymour on this platform, the main objective was seeking to bridge the divide between all three Chesnut movements in order to present a united front against Lincoln. It turned out that waiting to see the military situation was the correct move, for the dropping fortunes of the Union and the rising demands for peace obviated the earlier objections of the National Unionists and the Tildenites’ desire for moderation. Consequently, the convention issued a call for a second meeting in Chicago on September 5th, to which both Tilden and Johnson agreed. All signs pointed to the consolidation of the opposition in a single anti-Lincoln ticket, to be helmed by Tilden for President and Johnson for Vice-President, under Vallandigham’s plank that had at its center the calling of a convention of the states with the Union as the only condition.

The call for the Second Chicago Convention was clear in its priorities. “After four years of failure to restore the Union by the experiment of war”, it declared, “[we] demand that immediate efforts be made for a cessation of hostilities, with a view to an ultimate convention of the states, or other peaceable means, to the end that, at the earliest practicable moment, peace may be restored on the basis of the Federal Union.” These terms, James McPherson notes, “made peace the first priority and Union a distant second”. At best, they contemplated wide concessions to the Confederates; at worst, they were a complete capitulation, for it pledged to call for an armistice

first before negotiations could start. Delighted rebels recognized quickly that if an armistice was called, this was tantamount to their independence, for fighting could be hardly resumed once stopped and the Confederates could easily stall any peace talks. The plank “contemplates surrender and abasement,” said a Republican. "John Breckinridge might have drawn it”; Alexander Stephens for his part declared joyfully that “it presents . . . the first ray of real light I have seen since the war began.”

In one of those strange parallels in history, Lincoln in the summer of 1864 decided on the same course Breckinridge did in the summer of 1863. In those days, when the Confederacy seemed to be at the brink of destruction, a despairing Breckinridge made his Cabinet sign a promise to sue for terms for peace if the war took an even worse turn. The Confederate President hadn’t allowed his Secretaries to read it, but they still loyally endorsed that blind memorandum. Now, the Union President produced a blind memorandum of his own. “This morning, as for some days past, it seems exceedingly probable that this Administration will not be re-elected”, Lincoln wrote in pessimism. “Then it will be my duty to so co-operate with the President elect, as to save the Union between the election and the inauguration; as he will have secured his election on such ground that he can not possibly save it afterwards.” Lincoln’s cabinet all signed it as well. The Union cause, it seemed, was lost. But then, on September 3rd, a telegram arrived at the War Department, from General Thomas. It announced that “the enemy has yielded Atlanta to our arms. The city is ours”. A week later, on September 10th, a telegram arrived from General Sherman, informing the government that “Mobile is ours, and fairly won”. “Glorious news this morning—Atlanta and Mobile both taken at last!!!”, cheered the exuberant George Templeton Strong. “It is (coming at this political crisis) the greatest event of the war.” And Strong was not exaggerating, for these twin blows against the Confederacy revived the Yankees’ flagging morale, brightened Lincoln’s prospects, and allowed the Union to continue the fight onto its ultimate victory.