In many ways, it was “a cruel trick of fate” that decided that Louisiana would be the first of the Deep South states to be Reconstructed. Long time divided by economic, cultural, and racial lines, affected by violent, corrupt, and factional politics, Louisiana was certainly less than ideal for any political experiment. Even under normal circumstances, reconstructing such a state was a difficult task. But making Louisiana an example for the reconstruction of all other Confederate states seemed to be all but impossible. Consequently, it was rather unfortunate that Louisiana had become the “real test” of Reconstruction as envisioned in President Lincoln’s Quarter Plan. The implementation of this program in such imperfect circumstances would quickly result in the start of several bitter contests, as the revolutionary implications of Reconstruction opened the door to showdowns between Conservatives and Radicals, the President and Congress, and White and Black people, over the meaning and objectives of Reconstruction.

Louisiana’s Reconstruction began when the Union Army took New Orleans in late 1862. The victory of Farragut’s gunners and the occupation of the Confederacy’s largest city gave the Union government control over “a cosmopolitan and politically active population which had voted overwhelmingly against Breckinridge in 1860”. The population of the areas under Union control included planters of Whiggish sympathies, transplanted Northerners involved in banking and business, European immigrants who often brought enlightened ideas with them, and a sizeable free-black population, whose prosperity, education, and light-skin distinguished them from the majority of Southern African Americans. All these factions were quick to pledge loyalty to the Union, including wealthy sugar and cotton planters who seemed ready to resume their allegiance to the National government due to their backgrounds as Whigs and Conditional Unionists – or, just as likely, to obtain trade permits and perhaps delay the end of the slavery.

The military commander, General Burnside, was not a radical, but his zeal to punish treason and his willingness to use violence to end dissent, meant that the Proclamation was enforced extensively despite protests from planters and ladies that emptied chamber pots on his and his soldiers’ heads. Slavery soon started to completely disintegrate in Louisiana, the efforts of many planters to prevent that proving to be ineffective. As General Banks, sent by Lincoln to inspect Burnside’s administration, bluntly told a group of loyal planters, “theories, prejudices and opinions based on the old system” had to be discarded, and it was in their best interests to embrace a new order based on free labor. But as in other parts of the South, “free labor” as managed by the Army seemed at first like a cruel mockery. Indeed, although the Army had pledged to protect the wages of Black laborers and guarantee them food, medical care and education, the regulations issued by the Army “bore a marked resemblance to slavery” – sometimes, at least, for Burnside’s inadequacy as an administrator meant that most often creating and enforcing regulations was up to the local commander.

Consequently, instead of a single Reconstruction with clear objectives, Reconstruction in Louisiana was at first disorganized and divergent, some areas undergoing a process under the control of the Free State Association and the Bureaus, others one led by Conservative Army officers and loyal planters. All factions well understood that this “period of chaos and confusion” had to eventually give way to a definitive model for Reconstruction. The stakes were raised by the fact that, even months before Lincoln issued his proclamation of amnesty, it was becoming apparent that Louisiana would be used a testing ground for Reconstruction policies that would then be copied throughout the rest of the South if successful. As one of the leaders of the Free State Association, Benjamin Flanders, said, a Radical victory in Louisiana would be “the galvanizing shock that will traverse the rebel states and lead to freedom’s triumph in each of them”.

Benjamin Franklin Flanders

In this struggle for taking over Louisiana’s reconstruction process, the Radicals initially had the upper hand. The “more dynamic faction”, the Radicals included many men whose presence “would not have surprised anyone familiar with the leadership of radical movements in contemporary Europe, for the delegates included reform-minded professionals, small businessmen, artisans, civil servants, and a sprinkling of farmers and laborers.” Opposing them were conservative planters who hoped to preserve the framework of slavery and thus White Supremacy, even if slavery itself was doomed. To do so, they urged the President to allow election of new state authorities under the existing Louisiana constitution, a step that would prevent the enactment of further changes the Radicals desired, such as Black suffrage.

In any case, by middle-1863, following the victories at Liberty and the creation of the Bureaus, Lincoln endorsed the program of the Free State Association, which included as its cornerstone the organization of a constitutional convention

before a state government was elected. This represented a bitter defeat for the Conservative faction, who still clung to the idea of Reconstructing the state under the existing constitution. Lincoln’s endorsement allowed the program of land redistribution and radical reform to finally flourish in Louisiana, a state where loyal planters and reluctant Army officers had prevented the question of land and labor from advancing beyond the increasingly discredited formula of “coerced free labor”.

But the Radicals were uncharacteristically reluctant to take the initiative to politically Reconstruct Louisiana, because they were painfully aware of how unpopular they were with the White population of their state. Thus, neither the Radicals, who wanted to delay Reconstruction until universal suffrage was enacted, nor the Conservatives, who did not want to replace the existing constitution, took the initiative to reconstruct Louisiana. This was disappointing news for Lincoln, who sincerely believed that a quick Reconstruction could end the war faster. The Louisianans, the President sullenly grumbled, wanted “to touch neither a sail nor a pump, but to be merely passengers, —dead-heads at that—to be carried snug and dry, throughout the storm, and safely landed right side up.” Lincoln instead invested his hopes on Burnside, whom he pushed to hold elections. “Do not waste a day about it,” Lincoln ordered. “Follow forms of law as far as convenient, but at all events get the expression of the largest number of the people possible.”

But Burnside, immersed in an attempt to aid Grant in his campaign for Vicksburg, found little success. Aside from New Orleans elections that had sent Hanh and Flanders to Congress, something that in practical terms accomplished little because the Congress refused to seat them, no great progress had been made in several months. Not even the victory at Mississippi was enough to save Burnside, because although the Army of the Gulf was instrumental to the triumph the bluecoats fought under the command of General Rosecrans, who was merely on loan and remained officially a subordinate of General Grant. Furthermore, whatever his flaws, Burnside was an honorable man that refused to advance his career at Rosecrans’ expense. It also seemed that the General realized that he was in over his head, his letters revealing a certain relief at being transferred to the Army of the Susquehanna and away from those murky political waters he had never quite learned how to thread.

Soon after Burnside’s dismissal, a Washington correspondent informed Hahn that “rumor is . . . Old Abe is quite tired of that ‘rail’, and he wants to split it as soon as possible”. This meant that the new commander was expected to take decisive action to reconstruct the state. On the left, Radicals pushed for General Benjamin Butler, whose “steel resolve in favor of liberty and iron first against traitors” had facilitated if not resulted in Maryland’s reconstruction. But Lincoln did not trust Butler, a shifty political general. It’s ironic, then, that he chose Nathaniel Banks instead, another political general who was every bit the schemer as Butler.

An anti-slavery Democrat, then a Know-Nothing and finally one of the founders of the Republican Party and the first Speaker it elected, Nathaniel Banks was a political general who still commanded great influence within the party. Lincoln placed high hopes in Banks, but they were to be bitterly disappointed. At first, Banks had seemingly thrown himself fully into reorganizing the Louisiana administration, injecting much necessary order and energy into a state that had languished in lethargy and confusion under Burnside. Banks sent a delegation of free Blacks to the plantation bell to “ascertain what the negroes wanted.” They found that for the freedmen freedom meant “the sanctity of the family, education for their children, the end of corporal punishment, and payment of reasonable wages”. Banks cooperated with the Bureaus to create new regulations that “substantially increased wages and required planters to supply laborers with garden plots, permitted the freedmen to choose their employers, and allowed black children to attend schools financed by a property tax.”

But the critical matter of how the political reconstruction of Louisiana was to proceed remained, and Banks, more preoccupied with planning a campaign against Texas, had seemingly no plan of his own. Appointed in September, almost four months later no tangible advance had been achieved. Almost immediately after he delivered his Proclamation of Amnesty, and aghast at the prospect of further delays, Lincoln firmly told Banks “that in every dispute, with whomsoever, you are master”, and ordered him to "go to work and give me a tangible nucleus, of any color, which the rest of the State may rally around as fast as it can, and which I can at once recognize and sustain as the true State government”. Lincoln later explicitly told Banks to comply with the Proclamation and enroll Black voters as well, “the very intelligent, and especially those who have fought gallantly in our ranks”, as a step that would help to “to keep the jewel of liberty within the family of freedom”.

The provisions of the Proclamation left Banks frankly dismayed. Though he later claimed, perhaps in an effort to ingratiate himself to Congressional Radicals, to have been personally in favor of Black suffrage, the general thought that “every Negro vote cast will inevitably keep . . . a hundred loyal White voters from the ballot boxes. No Southern man will be willing to vote side by side with a colored man, however worthy the latter is.” Calling a Constitutional Convention first would, moreover, result in legislators debating “every theory connected with human legislation”, causing “fatal delay”, while a tentative plan to declare slavery “inoperative and void” by military fiat and hold elections under the old constitution could speed up the process. Willing to admit that the Maryland Constitutional Convention had reached a “happy consummation”, Banks nonetheless reminded Lincoln that two elections and extensive disfranchisement were needed for that result. Finally, the General warned that “revolutions which are not controlled and held within reasonable limits, produce counter-revolutions.”

Unhappily for Banks, Lincoln rebuffed him, possibly to quiet down Radicals who were already finding the Quarter Plan’s limited suffrage and lack of concrete reforms unpalatable. Realizing that the Quarter Plan

was the moderate choice, Banks moved forward with it, ordering Attorney General Thomas J. Durant to enroll all “loyal voters, regardless of color”. But even this limited concession had profound effects, for it opened the “door of opportunities” to New Orleans’ Free Black community. Indeed, limiting the vote to the literate and veterans, and adopting a model of reconstruction that would inevitably turn off some White voters, seemed to prep the stage for the

gens de couleur libres to assume a new protagonic role.

As mentioned previously, the Free Black community of Louisiana was unique, different not only the enslaved but also other free people of color. Light-skinned people who spoke French too, or sometimes only French, experienced in skilled crafts and capable of affording education in private academies in New Orleans or even in Paris, this “Mulatto Elite” was characterized by its wealth, social standing, and education. As Carl Schurz concluded after speaking with one of them, “There is no country of the world, save this, in which he would not be received as a gentleman of the upper class”. Steadfast Unionists, they were some of the most enthusiastic supporters of Black soldiers in the Union Army, providing two units with their own officers to General Burnside, which would then valiantly take part in the Battle of Liberty under Rosecrans’ command. A self-conscious community which felt that the time had come to finally acquire equality, they were also the staunchest proponents of Black suffrage.

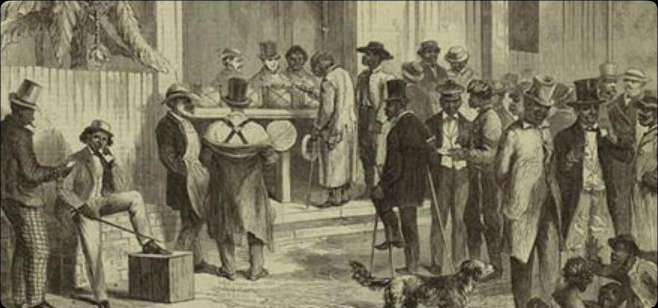

The New Orleans Creoles were distinguished by their wealth and culture from other African-Americans

However, the Free Black community tended to separate itself from the enslaved, whom they considered to be beneath them. “Some believed that they would achieve their cause more quickly if they abandoned the black to his fate”, radical editor Jean-Charles Houzeau wrote. “In their eyes, they were nearer to the white man; they were more advanced than the slave in all respects. . . . A strange error in a society in which prejudice weighed equally against all those who had African blood in their veins, no matter how small the amount.” Consequently, the qualified suffrage of Lincoln’s plan was at first perfectly acceptable to them. Only a few Radicals remained disgruntled and willing to fight for universal suffrage, including Durant who clamored that “There could be no middle ground in a revolution. It must work a radical change in society; such had been the history of every great revolution.”

Having isolated his opponents and obtained the favor of others through patronage, Banks moved forward. In February 1864, elections were held for a Constitutional Convention under the terms of President Lincoln’s Quarter Plan. Turnout amounted to 26% of the 1860 total, barely crossing the threshold set by Lincoln. It’s estimated that 90% of eligible Black voters turned out, representing 40% of the total vote even though the African Americans who fulfilled the requisites constituted a certainly lower percentage of the total population. No Black delegate was chosen, Banks having persuaded them not to, convinced that presenting Black candidates would dramatically drop turnout. Nonetheless, the convention would have a smashing majority of Moderate Unionists, committed to the end of slavery and capable of reluctantly swallowing limited Black suffrage. It seemed, for all intents, like an enormous triumph for the President’s policy.

The Louisiana Constitutional Convention, hastily assembled just a month later, was similar to other Conventions held during the war. Largely made of men committed to overthrowing the planter aristocracy but not friendly by any means to Black equality, the Convention made New Orleans the new state capital, declared that representation would be based on voters, established a minimum wage and nine-hour day, and created a system of progressive taxation and, for the first time, public education. Slavery’s demise was by then a fait accompli, but the Convention made sure to include a provision abolishing it. “Rhode Island or Massachusetts is as likely to become a slave state, as Louisiana is to reestablish the institution”, celebrated Banks. With the end of slavery also came the end of the planter class’s political power, which had been used “for the sole and exclusive benefit of slaveholders” in the antebellum. Emancipation, concluded excitedly the convention’s president, was “the commencement of a new era in civilization . . . [a] dividing line between the old and worn out past and the new and glorious future.”

But just like in Maryland many of the delegates were reluctant, if not outright hostile, to anything that seemed to advance Black rights. Unlike Maryland, where military fiat and wide disfranchisement had increased Radical power, in Louisiana the Radicals were much weaker and rather unable to counter the conservative proposals – in fact, the Radical factions was the smallest, even smaller than the pro-slavery planters turned Unionists. “Prejudice against the colored people is exhibited continually,” a spectator informed Secretary Chase, “prejudice bitter and vulgar.” At its most extreme, some delegates praised slavery as a “most perfect, humane and satisfactory” system of labor, mourning its demise, and pushed the “illogical demand” that all Black people were expelled from the state. This was “a most queer exigency”, a delegate remarked, coming from a Convention elected partly by Black voters and guarded by Black troops.

The 1864 Louisiana Constitutional Convention

Only through a lot of “cajolery, threats and patronage” was Banks able to force the Convention to accept Black education and maintain the limited Black suffrage of Lincoln’s formula, whereas some delegates had originally pushed for a clause that forbade both, in blatant defiance of the President’s wishes. Nothing could be done regarding more profound changes, such as endorsing the Bureaus and land redistribution, which meant that the land that had already been redistributed did not have a secure title. The people of Louisiana, a conservative man wrote, were “willing hat the State should be free, but they cannot stand Radicalism.” Altogether, the result was a defeat for the Radical faction, which Radicals, both in Louisiana and Washington, interpreted as definitive proof that universal manhood suffrage was urgently needed if the new South was to be reconstructed in all aspects.

Overall, whereas the Maryland Constitutional Convention had been a ray of light for the Radicals, the Louisiana Convention was a bitter disappointment. Even after the Convention concluded its work, the constitution being ratified at the same time as Hahn was elected governor in May (after a campaign where he called his opponents the “Negro equality men”), no great changes seemed forthcoming. Land redistribution continued, but its legality was seriously under question, and the freedmen who worked in plantations were still subject to the humiliating pass system and forced to sign yearly contracts. Even as Lincoln claimed that the new constitution was “better for the poor black man than what we have in Illinois”, a Treasury agent concluded that the wages were so low that the freedmen were condemned to “a state of involuntary servitude” that practically amounted to serfdom. In the words of Frederick Douglass, the current system made the “Proclamation of 1862 a mockery and a delusion”. “Any white man subjected to such restrictive and humiliating prohibitions”, a newspaper concluded, “would certainly call himself a slave.”

Altogether, this implementation of the Quarter Plan left the Radicals with a deep sense of betrayal, for if this was what the administration considered a successful Reconstruction then the conclusion was clear: Lincoln’s plans had to be entirely scrapped and replaced before they could give way to a “true Reconstruction”, defined in Radical circles as one that fully embraced Black suffrage and equality under the law. This inevitably set the stage for a showdown between the President and Congress over Reconstruction, as Lincoln sought to defend and expand the Quarter Plan while Congress struggled to create a policy of its own. “The tangled threads of dissatisfaction with events in Louisiana, concern for the fate of the freedmen, and rival definitions of loyalty to the Union” would soon come together and produce a bill that many a historian has considered a formal, open challenge by Radicals against Lincoln on the Reconstruction issue.

In truth, the situation is more complex. The legislative process, it must be emphasized, is long and arduous. The Reconstruction Act that was finally approved in May was the result of long debates held over the precedent months, when the situation in Louisiana was not clear at all and the ramifications of Lincoln’s Reconstruction plan hadn’t materialized yet. Radical opposition would quickly harden once the disappointing results were clear, but at first “few demurred”, for Lincoln and the Radicals agreed “on the crucial question of 1863—whether emancipation must be a condition of Reconstruction”. Indeed, some of the men who most bitterly opposed the President’s policy also cheerfully celebrated it when it was first announced, because in spite of its later conservative reputation at the moment a Proclamation extending the franchise to Black men and confirming land redistribution was certainly revolutionary. An oft-repeated anecdote has a stumbling Ben Wade, “affected by a most inexplicable dizziness and headache”, celebrating in the halls of Congress (for what it’s worth, Wade always denied it).

Jean-Charles Houzeau is an example of a European radical who committed his energies to Black civil rights

The bill, then, cannot be completely understood as a sign of Radical hostility against Lincoln. To fully comprehend it, it’s necessary to analyze its origins, the intentions of its framers, and the ideological point it tried to revindicate. In its final form, the bill did contribute to raising tensions between the President and Congress, Radicals and Moderates, but one cannot ignore how the bill came to be in the first place in order to understand why and how its making, passage and the actions that followed redefined the divisions within the Republican Party and through that redefined Reconstruction itself. The influence of Republican presidential politics cannot be understated either, for many looked forward to an opportunity to replace Lincoln with a candidate closer to their ideologies, while at the same time frankly suspecting that Lincoln only favored a quick restoration of the rebel states as a way to secure more votes for his renomination and reelection.

At the center of the issue, however, there was a genuine desire on the part of Congress to give a firm legal and constitutional basis to the Reconstruction process, something it had thus far lacked, being based on Lincoln’s war powers and military expedients. Some conservatives had already pointed out that the Lincoln administration maintained that the Confederate states had never actually left the Union, which would imply that the Federal government had no power to interfere with their “internal affairs”, such as slavery. At one level “all Republicans subscribed to this theory of indestructible states in an indissoluble Union”, because to say otherwise would give legal legitimacy to the Confederacy. But they also recognized and accepted that the National government would have to interfere in the Southern states to reorganize and reintegrate them, even if they didn’t agree on the extent and objectives of that intervention. Different constitutional theories were developed to justify this unprecedented exercise of National power.

On the one hand, some Radicals argued that by rebelling the Southern states had lost their constitutional rights. Stevens asserted that once liberated the rebel states would be “conquered provinces” subjected to the will of the conqueror; Sumner, for his part, believed that they had committed “state suicide” and reverted to the condition of territories, a formula that placed more restrictions on the government but still gave it wide powers to shape and reorganize the South. This “territorialization” program was popular with some Republicans, and, after a lot of negotiations, a bill to give territorial governments to the South was passed by the House in late 1862. But the bill died in the Senate after Lincoln expressed constitutional and practical objections, pointing that a Congressional law that turned states into territories was most likely unconstitutional. However, Lincoln’s objections, and the support of some Republicans, came mostly from the fact that the bill would take the Reconstruction process out of the President’s hands and give it entirely to the Congress.

A new theory that could conciliate the Congress and the President by giving them dual responsibility over Reconstruction was then developed. Article IV, Section 4 of the Constitution declared that the Federal government had an obligation to “guarantee to every state in this Union a republican form of government”. In the usual ambiguity of the US Constitution, this article did not define what a “republican form of government” was, but it “certainly discountenanced rebellion” and, interpreted correctly, could mean slave emancipation and even Negro suffrage. This constitutional interpretation was joined by a new doctrine, first articulated by the

Atlantic Monthly in the fall of 1863. The rebel states, the editorial said, “will not cease to be enemies by being defeated. They have invoked the laws of war, and they must abide the decision of the tribunal to which they have appealed. We may hold them as enemies until they submit to such reasonable terms of peace as we may demand.” Richard Henry Dana then popularized the doctrine in a speech in Faneuil Hall, arguing that the “conquering party may hold the other in the grasp of war until it has secured whatever it has a right to acquire”.

Black voters in New Orleans

The “grasp of war” doctrine was popular among Republicans because it smoothed over factional quarrels and did not entrust exclusive power over the seceded states to the President or Congress but allowed them both to influence and direct the process. But among Republicans, both Radicals and Moderates, the conviction remained that the only way to give Reconstruction a firm and legal basis was through legislation. They believed that Lincoln’s proclamations and actions were temporary expedients, founded in his military powers, which would give way to normal constitutional restrictions as soon as the war was over. “I fail to perceive that any one of the President’s proclamations . . . has vacated the constitution or laws under which the institution of slavery is protected and sustained,” said a representative. Most Congressional Republicans agreed and argued with “nearly universal conviction that some congressional enactment on Reconstruction, almost any enactment, was a legal and practical necessity”.

Consequently, by the end of 1863 Republicans were convinced that the only way to assure emancipation and begin the reconstruction of the South was through the “binding, sovereign will of the nation as expressed through its legislative channels”, that is, a law. This would naturally give Congress more influence over the scope, conditions, and objectives of Reconstruction, but Lincoln would form part of the process as well through his veto power. Reconstruction “must be done by the concurrence of the legislative and executive powers,” concluded Winter Davis, “without that, it is nothing”. To enact this vision, as soon as Congress met for its December session it created a special committee to “report the bills necessary and proper for carrying into execution” the “guarantee a republican form of government” clause of the Constitution. This would become the Select Committee on the Rebellious States, chaired by Winter Davis, and dominated by Radicals.

Altogether, historian Michael les Benedict concludes that regardless of party politics and the Louisiana situation, all Republicans “desired the passage of a Reconstruction measure for practical reasons relating primarily to law and what they believed to be the proper principles of government”. It was based on these beliefs rather than in simple doctrinaire opposition that politicians like Winter Davis denounced the Amnesty Proclamation as “a grave usurpation of the legislative authority of the people” as soon as February, when no one was sure of how the Louisiana experiment would turn out. Even people who supported the President, such as Congressman Longyear, who called the Proclamation “a bright and glorious page in the history of the present Administration”, conceded that it was “incomplete” for “lack of constitutional power that can be conferred by Congress alone”.

The agreement of most Republicans on the necessity of the law does not mean that there was consensus regarding its actual details, as Radicals naturally saw in the bill a way to push forward their agenda, mainly Black suffrage. But, surprisingly enough, the battle did not center on Louisiana, but rather on Montana. After a bill was passed granting a territorial government to Montana in February, the Senate amended it to delete the word “white” from the voter qualifications, in effect instating Black suffrage in the territory. This was a purely ideological move. Even Senator Wade, who was in favor of the change, had to recognize that they were “legislating in reference to shadows”, for no Black men resided in Montana. It was a test of Radical strength, because if Congress could not agree to impose Black suffrage on a territory, where it undoubtedly had the authority to do so, it could hardly be expected to impose Black suffrage on the South, where its authority was contested.

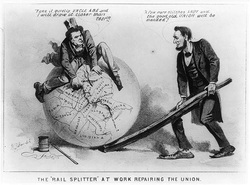

The Grasp of War doctrine was used to justify the imposition of different measures on the conquered South

The Senate amendment was readily agreed upon by House Republicans even in the face of determined Chesnut opposition. It’s been suggested that, with the President having asserted his right to require Black suffrage in the South, the Congress wanted to vindicate its own power. But the passing of the act had an unexpected consequence: it revived territorialization as a viable doctrine. The original bill written by Representative Ashley was then replaced by one written by Winter Davis, who, concluding that the President was “thoroughly Blairized”, proposed to declare all rebel states territories, which would have to elect Constitutional Conventions to draft new constitutions that had to abolish slavery, declare equality under the law, and provide Black people with land. Originally, the bill also forced universal manhood suffrage both on the elections for the Convention and the resulting constitution, but ultimately this was defeated in favor of retaining Lincoln’s qualified suffrage alongside the disenfranchisement of all rebels for at least five years. The constitutions would have to be approved by Congress and then by a referendum where at least 50% of the vote of the 1860 election had to be gathered. After being approved, the states could not amend the constitutions for ten years at least without Congressional approval.

The bill responded to several concerns among Republican circles, but the overreaching one was the desire to delay Reconstruction until after the end of the war. The threshold of 50% was one that no Confederate state could reach, preventing a Reconstruction like the one underway in Louisiana, Arkansas, and Tennessee. In those states Republicans charged that the “unchanged white rebels” would be the ones in charge. As Senator Howard said, the American government could not “say to the traitors, ‘all you have to do is to come back into the councils of the nation and take an oath that henceforth you will be true to the Government'”. In actuality, the requirement of an oath was not as lenient as they feared, since “Lincoln offered amnesty only to those who made a conscious decision to abandon the insurrection while it still had a chance of success”, something that, according to Carl Schurz, meant that his state government were “substantially in the control of really loyal men who had been on the side of the Union during the war”.

One of the great problems the bill had, insofar as Lincoln was concerned, was that it did not respect the voluntarism that had become a cornerstone of Presidential Reconstruction. In this context, voluntarism refers to Lincoln’s wish that the new conventions be a result of the voluntary free will of Southerners. His Reconstruction plan was envisioned as essentially an enabling act which, despite the presence of a “few necessary conditions”, still left Southerners themselves in charge. The Congressional bill, by contrast, was clear about who was in charge – and a constitution created essentially by Congress could not be considered the fruit of the people’s will but coercion by the National power. Some Republicans maintained that Lincoln was similarly coercing the Southern states, but the President argued that, just like a “man’s house is still the fruit of his labor and will even if he builds it according to a manual”, the new constitution would still be the result of the Southern will “even if they are drafted according to the Constitution”.

In its original form, the Reconstruction bill, also called the Southern Territories bill, was too radical for most Republicans. It was not so much the territorialization program that aggravated the moderates, for the idea commanded more than enough support to pass the bill even if several Republicans defected. Rather, it was that its terms would scrap away the governments Lincoln had already created, which, Moderates feared, would alienate the President. In practical terms, most Republicans endorsed the bill as one that would give Reconstruction a firm legal basis, that would ensure emancipation and the freedmen’s rights, and that would give the National government the capacity and power to oversee Reconstruction and assure its success. But they still did not wish to defy the President so openly.

By April, as the situation in Louisiana became clearer, some Republicans were declaring Lincoln’s Reconstruction a dismal failure, such as Winter Davis, who bitterly said the new Louisiana government was merely a “hermaphrodite government, half military and half republican, representing the alligators and frogs of Louisiana”. Anti-Lincoln Congressmen like him saw no problem in a measure that scrapped those governments, but it was clear that Moderates were not going to acquiesce in that. Thus, an amendment was accepted that declared that the bill did not apply to states where Reconstruction had already started under the terms of the Quarter Plan – meaning, Arkansas, Louisiana, and Tennessee, where Constitutional Conventions were being or had been organized. Many Radicals only accepted this reluctantly, considering that allowing those government to stand would condemn the freedmen there to “enduring slavery”. But, as Senator John P. Hale said sadly, they were compelled to “waive my conscientious scruples and go for expediency”.

At the end, it’s truly remarkable that most Republicans voted in favor of such a radical bill. Some defections did happen, but they were truly in the minority, the party having embraced limited Black suffrage, land redistribution and National oversight over Reconstruction. Most Republicans, Radical and Moderate, seemed to have sincerely believed that Lincoln could not find issue with the bill. They thought that in practical terms its dispositions were the same as those of his proclamation, and that having allowed his governments to stand the President would sign it. But Lincoln could not accept the Southern Territories bill due to irreconcilable differences. In the first place, by delaying Reconstruction until the war ended the Congress would prevent Reconstruction from working as a weapon to defeat the Confederacy. Second, Lincoln honestly considered territorialization an unconstitutional proposal that would do more harm than good, because giving the National Government so much power would make it clear that Southerners were a conquered people at the mercy of Congress; the voluntarism of his plan would, by contrast, better conciliate them to their defeat and be more in line with classical American principles. Finally, and even though the bill still gave him a major role in Reconstruction, Lincoln did not wish to accept a plan that bound him to a single course and left Congress the indisputable master of the situation.

Lincoln vetoed the bill a little over a week after it was passed in May. The story goes that when the clerk arrived with a message, a smiling Senator Chandler asked whether it was the announcement that the President had signed it. When the clerk answered that it actually was a veto, the gaping Chandler could only stand there, “paralyzed in denial” for long minutes. When they recovered from shock, Radicals were outraged at Lincoln’s opposition to a bill that was “eminently needed and manifestly just”. An attempt to override the veto took place immediately, even though the bill had not received anywhere close to 2/3rds of the votes when it was first passed. But now it could not even gather a majority of either House, for many of the men who voted in its favor now voted against the override.

Lincoln’s actions redefined the factions within the Republican Party. Instead of defining one’s position according to his support for Black suffrage, Black landownership and other such issues, now Radicals would be the ones against Lincoln’s program, and Moderates the ones in favor. The result was increasing the President’s influence at the expense of Radicals, who saw their power and numbers diminished. As Winter Davis grumbled, it was not that Republicans had suddenly discovered that the bill “violates the principles of republican government”. Rather, “it is the will of the President which has been discovered since”. The sting of the failure was so painful that Senator Wade and Representative Davis ended up issuing a manifesto that accused Lincoln of “executive usurpation” through a “rash and fatal act” that was a “blow to the friends of his Administration, at the rights of humanity, and at the principles of Republican Government”, that would “return to power the guilty leaders of the rebellion” and assure “the continuance of slavery”.

The veto of the Southern Territories Bill left Lincoln as the undisputed master of the situation

Following the failure of the veto override, Radicals shifted their efforts towards replacing Lincoln with a candidate more amiable to their positions and taking charge of the 13th Amendment that was being drafted simultaneously, to consecrate there the principles of liberty and equality, and their vision of what Union victory meant. If Lincoln could not be replaced, Radicals were ready to create a new party and issue a challenge from his left. This meant that, even though Lincoln managed to maintain control over Reconstruction through his actions, he also galvanized a powerful anti-Lincoln movement that could divide and destroy the Republican Party if he was not careful. But this Congressional struggle was not the only reason behind this expanding breach, for the first months of 1864 also saw the Confederacy return from the brink and engage in a final, supreme bid for Southern independence that shocked the North and made many give into despair once again.

( sorry, you have to read for it to make sense

)