One of Lincoln’s many woes in the winter of 1861-1862 was the conservative reaction to his policies and also to the proposals of Congress’ Radical Republicans. These Radicals continued to push forward with an agenda that had as goals not only the complete destruction of slavery, but also a gigantic social and economic transformation that would erect a new South based on the principles of Free Labor, Liberty and Equality. They had taken many steps forward during the session of July-August, and now Congress was back in session. Even if the President was not ready to embrace “the glorious Second American Revolution”, as one called it, they would have to drag him along.

The main reason behind the President’s reluctance was his aversion to “a violent and remorseless revolutionary struggle”. Yet, Lincoln commented that the worst had passed in the Border States. and that Unionism was firmly asserting itself. Moreover, he invited the Congress to further legislate on the subject of slavery, but asked them to avoid “radical and extreme measures.” Radicals hear him, but did not listen. They agreed with Moncure Conway when he declared that the Confederacy was “rebellion against the noblest of revolutions." Even before Lincoln had given his speech at the opening of the session, some Republicans had made it clear that they would take new steps to ensure the success of this new revolution.

As always, events or lack thereof in the military battlefield had an effect on the political stage. The lack of action in the Maryland theater frustrated Republicans, who demanded a harder war and accused Lincoln of expressing “too much tenderness for traitors.” Similarly, they had lost their faith in a secret Unionist majority in the South. For some, the only true Unionists in the South were the slaves, and even conservatives agreed that freeing them would be a hard blow against the rebellion. Lincoln agreed with them, not believing anymore that the Confederacy would be destroyed from within by hidden Unionists. But he still sought to apply a constitutional solution to the problem, and also to maintain command of the national policy regarding slavery rather than allow Congress to lead.

For that reason, Lincoln started to push for compensated emancipation in the Border States. Being that three of the four were under Unionists governments that opposed Confederate administrations, Lincoln had hopes that they would be more open to the abolition of slavery. Maryland and Delaware seemed the most promising choices. Delaware was obvious enough. Characterized by some as the “least Southern of the slave states”, it had also the lowest Slave population coupled with a relatively large community of free Blacks. In fact, Delaware had almost enacted gradual emancipation in 1847, failing by just one vote. Quakers and others in the Northern part of the state formed a nucleus of anti-slavery politics within Delaware.

Maryland, for her part, was promising due to the fierce Unionism of the Frederick government and the fact that most Maryland slaveowners and plantations had declared their allegiance for the Confederacy. Resentment on the part of the Maryland Unionists against the Slavocrats could be expected and used for abolitionist goals. In any case, the institution had been suffering slow but sure erosion as thousands of slaves escaped to Army lines.

Unfortunately, Lincoln’s hopes were frustrated by prejudice and Negrophobia. As Senator James A. Bayard said, the main obstacle was fear that abolition would lead to the “equality of races.” Lincoln had drafted a proposal to abolish slavery along a ten-year period, with both states receiving Federal compensation. This was indeed a momentous step, which conservatives opposed as unwanted and unconstitutional Federal interference in state matters. Overzealous radicals also criticized the plan for failing to recognize the “great fundamental principle that man cannot hold property in man.” But Lincoln made it clear that compensated, gradual emancipation was the only constitutional measure that could be taken in the Border States, where the Constitution still operated. As historian Eric Foner points out, “the plan made slaveholders partners in, rather than opponents of, emancipation, and offered a way of ending the institution without violence or social revolution.”

Both plans, nonetheless, failed miserably. In November 1861, George P. Fisher, Delaware’s at-large Unionist Representative, drafted a bill putting the Lincoln plan into motion. Immediately, conservatives sprung to action and attacked the bill, crying that the government had “no authority to appropriate the treasure of the United States to buy negroes, or to set them free,” and that abolition would lead to Black suffrage and racial equality. The opposition joined and by a solid vote defeated the measure decisively.

The Lincoln plan found no better welcome in Maryland. Since the Chesapeake counties and Baltimore had been under the control of the Confederacy until August, they were not represented at the Frederick government. Instead, most delegates came from the Northern part of the state, an area with few slaves whose economic health was linked with the North. But once again hate of the Negro frustrated the Administration’s efforts. Governor Hicks went as far as declaring that talking of abolition was “treason”, an ironic accusation that gathered much mockery by Republican newspapers. “Treason!”, one exclaimed, “how can abolition be treason? Abolition is simply the instrument through which treason will be suppressed.” The Frederick government refused to even consider the bill, which never went up for a vote.

Some have said that the proposals failed because Lincoln refused to endorse a plan of colonization that would remove the slaves from the states, and perhaps the US as a whole. As an Illinois National Unionist said, the people were not ready to set the slaves “loose in their midst.” Even Lincoln’s intimate friend Joshua Speed warned that people would not allow “negroes to be emancipated and remain among us.” Colonization was favored by conservative Republicans and anti-slavery men who shrank at the idea of racial equality.

As an idea, colonization was based on an oftentimes weird mix of racism, paternalist compassion and imperialism. It was advocated as a solution to the dangerous idea of racial equality by such men as Jefferson and Clay, the latter of whom had been described by Lincoln as his “beau idea of a statesman.” The American Colonization Society had founded Liberia in an attempt to put this plan into action, but it was clear that the effort was not going to succeed. The Blair family put forward another proposal for colonization in Central America and Haiti, which made the rounds before the war and during its first months.

Many colonizationists were motivated by open racism, saying that it "would relieve us from the curse of free blacks.” Underneath the idea of colonization was the belief that the United States should be a purely Anglo-saxon nation, and that the Negro was nothing but a “feeble and foreign” element. However, some Republicans supported colonization because they earnestly thought that prejudice could never be eradicated, and as such it was better for everyone if African-Americans left and build a respectable life for themselves elsewhere. One, for example, recommended Latin America because there “color is no degradation,” and Ben Wade also added that it’s "perfectly impossible that these two races can inhabit the same place and be prosperous and happy." Some, like the Blairs, also saw colonization as a way to advance American commercial interests and spread their culture and institution. Such praise is of course ironical and difficult to comprehend, for it subconsciously recognized that Blacks were thoroughly American in culture and customs, yet still supported their emigration, some going as far as proposing forced colonization.

Ultimately, colonization was not an attempt to solve a problem, but to sidestep it. Lincoln recognized as much when he said that “if all earthly power were given me, I should not know what to do, as to the existing institution,” back during his Senatorial campaign in 1854. Endorsing colonization was a way to ignore the difficult problem, but after he became a Senator he could no longer ignore it. Frederick Douglass would remark that Lincoln was completely free “from popular prejudice against the colored race.” But his experience with Black people was very limited. He had seen slaves while travelling down to New Orleans, and when returning home from Speed’s house at Kentucky, but it seems that neither experience left a deep mark. In the second, at least, he was wallowing in self-pity due to his breakup with Mary Todd, and would as a result comment that the slaves seemed “cheerful.” In small Springfield, his dealings with Black people were limited and brief, but he was always respectful.

Lincoln’s world-view started to change after he arrived at Washington D.C. For the first time in his life, he met Black leaders, and could see the horrors of slavery in person. True, he had served in Congress as a Representative, but his stint was brief and the sectional tensions were not as inflamed as in 1855. Now he returned as a more experienced man, in the middle of a great controversy. He met with important leaders of the African-American community, such as Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglass, who would become a friend and frequent advisor. He also saw firsthand the great opposition of the South towards any kind of emancipation or legal equality, and their praise for the institution he so despised undoubtedly left a deep and negative impression.

Colonization focused on Africa at first but then shifted towards Central America

Lincoln would mention colonization again during the 1856 campaign, when he became one of Frémont’s foremost speakers in Illinois. But Radical and Black leaders made it clear that they would not support any such scheme, and thus Lincoln’s opinions started to change. He did not mention colonization publicly again, though for obvious political reasons he could not come against it either, especially in a state like Illinois, where many disliked slavery but hated the Negro even more. As a result, Lincoln was forced to meet the issue of the future of African-Americans after emancipation, and he articulated his view of legal and civil equality that would allow for future economic equality, though he remained apprehensive about the prospect of social equality. Come the Civil War, Lincoln outright refused to entertain the Blair plans for colonization. This has been blamed as the main cause for the failure of compensated emancipation in Maryland and Delaware, but it’s unlikely that either state would have implemented the plan even if it went hand in hand with colonization.

Either way, it was becoming increasingly clear to the President that the Border South would not undertake emancipation by itself, and that the war could not be fought with “rose-water stalks” anymore. Criticism from the radicals also rose to a crescendo. Gideon Welles commented that the rebellion “rapidly increased the anti-slavery sentiment everywhere”, and he was right. Indeed, at the very start of the war, abolitionists were persona non-grata in several cities, their lives threatened by people who blamed them for the war. But “a wondrous change” took place after the fall of Washington. Part of it was, of course, the desire of revenge of many. But it also signaled a veritable shift in public opinion against slavery. "Never has there been a time when Abolitionists were as much respected, as at present," commented one in a letter to the veteran abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison.

An Illinoisan thought “that the people are far ahead of the leaders today in their readiness to take the proper steps to put down this rebellion.” But in truth, agitation in Congress matched and even surpassed the agitation of the people. Wendell Philipps gave many speeches before the Senate, demanding a “permanent Union, founded on permanent Freedom, that knows neither black nor white,…[and] holds an equal sceptre over all.” There was also great discontent over the President’s perceived lack of action over the slavery question. Garrison commented that Lincoln had “evidently not a drop of antislavery blood in his veins,” and a constituent wrote to his Republican congressman saying that “If this struggle ends with slavery still in existence, the Battle of Liberty has been only half-fought.”

The Radicals were also skeptical about the Lincoln plan for emancipation in the Border South. When the December session had just started, the plan had already failed at Delaware but there was some hope that Maryland could adopt it. Lincoln then asked Congress to appropriate federal funds to aid any state that undertook gradual emancipation, though he specified that the government was recompensating the

states, not the slaveholders.

Centrists praised the plan, some as a stroke against slavery, others as a policy that would deflate radical plans. Though the Radicals did not talk against it as openly as Conservatives did, they did see it as a half-measure that lacked the vigor needed. Stevens, for example, considered it “it is about most diluted, milk and water gruel proposition that was ever given to the American nation.” Others had little hope for its success. “I have never been able to discover a difference in views or feelings between a man from Maryland and a man from South Carolina or Alabama,” commented a congressman, who felt validated after the Frederick government refused to consider the plan.

In any case, the session of December 1861 passed or considered several bills that took greater action against slavery. It even annoyed Lincoln at times, making the President complain of “Jacobinism”, and other Republicans similarly chafed at how the Radicals considered themselves “the representatives of all righteousness.” But Lincoln also took meaningful action against slavery, such as negotiating and enforcing an anti-slavery treaty with Britain. It’s pretty telling that Lincoln, a man of great compassion, allowed a slave trader to be hanged as a pirate despite conservative pleadings for him to interfere.

He also worked together with Congress to pass many anti-slavery measures. After refusing to renew the Johnson resolutions, Republicans voted to partially repeal the Fugitive Slave Act, disposing that it could only be enforced in areas in peace away from the theaters of combat, which practically limited it to Delaware, and giving the protection of court testimony and habeas corpus to Blacks. A bill to abolish slavery in the District of Columbia and all territories was signed by Lincoln, though it liberated almost no slaves since the capital was still under Confederate occupation. It did provide compensation for Washington slaveholders who had fled to Maryland, and many accepted it because “slave property had lost so much value as to be worthless.” An abolitionist celebrated saying that “hen the army of freedom takes back the Federal city, it will also become a city of Freedom.” A law forbidding Army officers from returning slaves under threat of court-martial gave a final coup de grace to the Fugitive Slave Act for all practical purposes.

The most radical measure passed by Congress was the Second Confiscation Act. It confiscated all slaves of all persons engaging in rebellion or aiding it, thus going much farther than the First Act had gone. Some legislative fights had taken place over its wording and scope. The Radical Henry Wilson, for example, wanted the act to not merely authorize the President to confiscate the slaves, but to also require him to. Ultimately, the measure that was passed and signed into law gave Lincoln discretion over how and when he should enforce it. It also declared that the slaves liberated by the act would be forever free, a disposition that caused considerable conservative backlash. The government may take the enemy’s property, “burn his cities, devastate his fields, deprive him of his life, all of which are great intrinsic evils, but it is said that we may not perform that intrinsically righteous act— emancipate his slaves,” complained one of the act’s supporters.

The act originally also included a measure that had potential for great change – the confiscation of real property. Republicans could agree that liberating slaves was not a bill of attainder, but moderates like Lincoln thought that no legislative act or military measure could take a person’s estate. The bill was amended to specify that the forfeiture of real estate by disloyal citizens would not extend beyond the person’s natural life, and authorized the President to restore property through pardons. Afterwards, Lincoln signed the bill. Basically, the Second Confiscation Act allowed the President to free all the slaves of disloyal owners through a military proclamation, and disposed the confiscation and emancipation of the slaves of rebels in areas where the courts were still operative, such as Maryland.

These pieces of legislations are clear proof of the Administration's close and mutually beneficial relationship with the Radical Republicans. Despite his well-known moderate beliefs, many Radicals rejoiced as they saw that the President was coming closer to their side. "Mr. Lincoln," Stevens said, "has finally seen the light. He's now a wide-awake." Radical Republicanism has often been misunderstood, and this has led to misleading historical interpretations. Many portray the Civil War as the history of how Lincoln "evolved" and became a full-fledged Radical; others paint it as the tale of the wise Lincoln moderating these hot-headed Radicals in order to achieve real change. Neither interpretation is fully correct; one commits the fallacy of believing that there was always a predetermined end to Lincoln's growth, while the other sees him as a static figure that entered "the White House with a fixed determination to preside over the end of slavery and waiting for the northern public to catch up with him." This ignores the wider context under which Lincoln operated, and his own personal shortcomings. The truth is, both Lincoln and the Radicals influenced each others, and all of them were prey to events outside of their control, which shaped the next phase of the anti-slavery crusade and the ultimate destiny of the United States.

Thus, the moral arc of history, in this instance, bent towards justice. The circumstances of the time, such as the bitter failure of colonization and compensated emancipation, were one of the sources of the pressure that produced this bent. The Radical Republicans were the other great source. It is necessary, then, to fully comprehend their ideology and objectives. Radical Republicanism was, at its core, a form of political abolitionism, characterized by its moral sensibility and its, at times, single minded focus on slavery as the great challenge the American Republic would have to face. The Radical Republicans formed a much more cohesive group than their Moderate counterparts, being united by a common purpose and world-view. This enhanced their political influence, especially due to the uncertainty and fear created by the war. Ready to seize the initiative, the Radicals were seemingly the only Republicans with both a clear objective and a clear program to achieve them.

Radical Republicanism reflected, more than anything, the reformist spirit of many Northerners and their deep "commitment to reform the evils they saw in society". This "Yankee Puritanism" saw the government as an instrument for the enforcement of moral righteousness and firmly believed that "compromise with sin was itself a sin." Radicalism was born out of the religious revivals that swept the North in the 1830's, and as such it appealed mostly to the morality of the nation. However, this tactic was rather ineffective, and it would not be until the new conception of "political abolitionism" was developed that abolitionist became a coherent political movement. Salmon P. Chase, now Secretary of the Treasury, was the main architect of this new ideology, that focused not in moral appeals but in the threat of the Slave Power to the Constitution and the Northern way of life, a message that resonated much better with Northern voters who had no sympathy for the Negro but resented Southern dominance. Chase's invaluable contribution to the anti-slavery movement cannot be ignored, and when he passed away the New York

Tribune would justly proclaim that "To Mr. Chase more than any other one man belongs the credit of making the anti-slavery feeling, what it had never been before, a power in politics."

Nonetheless, the main tenet of Radical Republicanism remained a firm belief that slavery was

morally wrong. Radicals accepted arguments against the economic soundness of slavery, but for them the moral element always had to take precedence over other considerations. For example, the radical Joshua Giddings considered that opposition to slavery not fundamented on moral reasons was a "cold atheism", while James Russell Lowell believed that it was "in a moral aversion to slavery as a great wrong that the chief strength of the Republican party lies." Lowell's assertion was undoubtedly shared by the great mass of Radicals, men who put their ideology and their goals over their party and tradition. The result was that Radicals were not afraid to proclaim that they would simply bolt the party should the Republicans become too moderate, and since the Republicans could not rule without their support, they effectively became the political force that kept pushing the Republican Party to the left and prevented it from ever becoming a moderate movement built solely around Whiggish economic issues.

Anti-slavery propaganda was the Radical's main weapon. Characterized by Giddings as " the great and mighty instrument for carrying forward . . . reforms", political agitation was used by the Radicals as a way to influence public opinion. In the antebellum, they mostly focused on convincing people of the evils of slavery; in the midst of war, Radical agitation sought to push forward universal emancipation and, later, the acceptance of Black civil rights. Many moderates bitterly denounced the Radicals as irresponsible and incendiary, but rather than shaming them, the Radicals "readily admitted that they were political agitators; indeed, they were proud of the name." The anti-slavery agitation in which the Radicals engaged towards the end of 1861 has already been described at length in previous paragraphs. Suffice it to say that it was indeed very effective in pushing not just the Administration but the whole nation down the road of emancipation.

Radicalism, for the most part, had its home in New England and the areas of the North that had been settled by their Yankee immigrants. It was these "little New Englands", known by their high literacy, economic dynamism, and moralistic support for all kinds of reform movements from temperance to abolitionism, that provided the greatest support for the Republican party, which "from the moment of its birth, commanded overwhelming majorities" there. Whereas the Democratic Party and then the National Union had almost entire control of the great commercial cities, beyond them "wherever the New England people have sway, they came down like an avalanche" for the Republicans in all elections.

For a people that glorified free labor and saw the independent farmer and the respectable middle-class as "the only solid foundation of democratic government", the rural North was the true representative of American prosperity and democracy. This sometimes manifested in exaggerated contempt for the urban inhabitants of the Union, who were more moderate and willing to compromise than the people of the Northern countryside. These rural communities, "with their small towns and independent farmers", were centers "of Republican radicalism and heavy Republican electoral majorities." It was their support that guaranteed Lincoln's victory, and this meant that the opinions of the Radicals could not be merely disregarded as that of a few "ultras", but had to be considered as the will "of the mass of true and hearty Republicans."

Accordingly, the Radical leaders, with the notable exception of Stevens, "represented constituencies centered in New England and the belt of New England migration that stretched across the rural North." Many of them self-righteously declared that they were the only politicians guided by principles, but they were not entirely incorrect. Congressional Radicals ranged from the handsome and erudite, but egotistical and unlikeable Charles Sumner to the "perfect political brigand" Thaddeus Stevens, who exhibited a mix of idealism and pragmatism that led the young Clemenceau to declare him the "Robespierre of the Second American Revolution". United behind the goal of universal freedom, Radicals played a very important part in the developments that took place in the December session and would ultimately lead to a war for Union and Liberty.

Free Labor, for the Republicans, was not just an economic system, but the very model of a good society.

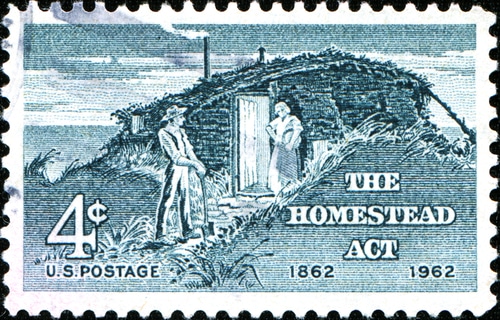

Radical Republicanism has sometimes been interpreted as merely an expression of Northern capitalism. But in truth, the Radical were not united behind any coherent economic program. The divisions between Radicals and moderates were blurred in this regard, for all Republicans broadly supported a Whiggish program of economic interventionism that laid down a blueprint for national development. Measures of great popularity among the Northern people that had been stalled for decades by the South could finally be enacted thanks to the withdrawal of almost every Southern congressman. National Unionists continued this opposition, but the Republicans were easily able to overcome them and pass bills for the creation of a homestead program and the building of a transcontinental railroad.

The Homestead Act "never measured up to the starry-eyed vision of some enthusiasts" who wanted to "give every poor man a farm", but it, along with the transcontinental railroad, allowed thousands of families to settle millions of acres of Western land, contributing enormously to the economic expansion of the United States but also, sadly, increasing the suffering and injustice committed towards the Indian. These measures were supplemented with further laws that granted public land for the building of more infrastructure and of colleges that would teach "agriculture and the mechanic arts". The legislation, altogether, helped "to people a vast domain, sprinkle it with schools, and span it with steel rails."

Charles and Mary Beard concluded that this process was the true Second American Revolution, for it helped to fundamentally change the balance of power within the United States and laid down the "blueprint for modern America." Thus, the "planting aristocracy of the South" was driven away from power and "the capitalists, laborers, and farmers of the North and West" took the reigns and transformed the United States into a modern industrial nation that clearly followed the ideal of 19th century modernity. The Civil War, one can clearly see, changed the North as much as the South.

The Homestead Act paved the way for the settlement of the American West.

The second session of the 37th Congress was one of the most active and important in American history. Aside from the enormous steps it took towards modernizing and industrializing the nation, the Congress managed through its actions to finally render “Freedom National, and slavery sectional” as Republicans had dreamed for so long. It also represented an enormous and significant turnabout at the Federal level, for now the government was actively working to undermine slavery. The session pushed forward the idea of emancipation, and contributed to a greater radicalization of the war. But it also caused a notable conservative backlash that would greatly distress Lincoln during the first months of 1862. Foreign diplomacy, McDowell’s next campaign, and how to deal with the reinvigorated National Union would keep Lincoln under constant pressure, as the war kept radicalizing.

__________________________

AN: One of the hardest things about writing a detailed TL like this is the fact that so much is going on at once. There are social, economic, political and military issues, and all take place in different theaters at different times. And of course, this is only the Union side. I will not sacrifice detail in favor of simplicity, but this does mean that I will sometimes have to left something to the side to explain another thing. Would you all prefer the next chapter to be about the conservative reaction and foreign diplomacy, or about McDowell's campaign?