Chapter 17: The War at the Courts and at the Sea

The bloody Battle of Baltimore caused wide celebrations through the Union, as thousands rushed to cheer the flag and the “gallant soldiers that so nobly upheld it.” President Lincoln was greatly pleased with the victory, and so were many politicians and important men. Among the people, it did a lot to soothe the still open wounds of the Fall of Washington; at the very least, it managed to restore a little of the Yankees’ confidence, and instill a certain pride in the men. General McDowell went from a little-known military man to a celebrated war hero in slightly more than a week. But while the people cheered, the full magnitude of how much the victory had cost started to dawn on the leaders of the Union.

The around 7,000 casualties already exceeded the total of the entire Mexican-American War. And the chaotic situation in Baltimore created ghastly scenes of violence that horrified people throughout the nation. When McDowell’s exhausted men wearily trudged back to their camps at Havre de Grace after a rather miserable welcome at Baltimore, civilians saw not jubilant conquerors but tired, almost broken soldiers. Lack of preparation and training, and the wholly inadequate Army Medical Bureau meant that the men were green as grass when they marched off to battle, thinking it would be a glorious but brief endeavor. In fact, there were some boys who hastily joined the Army because they thought the war may end before they had the chance to see fighting.

To be sure, enthusiasm among both the people and the ranks was still high, but the leadership started to realize the simple fact that defeating the South would be more than a simple question of marching. The first to realize so seemed to be Lincoln himself. Though discerning the man’s thoughts is somewhat hard, we do know that he felt mixed emotions upon learning all the details of the campaign. For one, he took joy in having achieved a victory, something that undoubtedly strengthened his government at a critical point. Yet the weight of those dead boys heavily hung on his shoulders. Always a man who looked forward rather than dwelling in failures and successes alike, the President was also somewhat disappointed by the fact that the rebel army hadn’t been destroyed. He was willing to overlook it this time, for he recognized that McDowell was doing the best he could with green troops and green officers. Nonetheless, the bitter taste of missed opportunities would unfortunately become a common one for Lincoln.

The rebels, for their part, had suffered as big a psychological hit as a material one. President Breckinridge saw it in person. He, at the bequest of Secretary Davis, travelled to Waterloo, the Confederate center of operations. But as he approached the small village, he saw a “terrible scene of human misery.” Indeed, the Confederate leader saw scores of stragglers, and hundreds of wounded men. There were but a few who could still stand, and even then, just barely. All the soldiers had little to say, except for one who told Breckinridge to “go back! We’re whipped!” The hearts of both Breckinridge and Davis sank. “Is this the end? Is my country going to end like this?” Breckinridge muttered to himself.

Confederate Infantry at the Battle of Baltimore

At one point, a soldier in a lathered horse came. “All is lost!” he cried, “the Yankees will cross the river. Leave sir, please!” Of course, soon after that Beauregard and his yelling rebels rushed forward and managed to finally halt the Federal advance for good, but for a moment Breckinridge probably really believed his Confederacy was going to end right there and then. His new nation secured for the moment, the Kentuckian showered lavish praise upon General Beauregard, though he made sure to do it discreetly, knowing how that would incense Johnston. His efforts were to no avail, for Johnston again complained that not many laurels were coming his way despite his “laborious and prominent role” in the campaign.

This proved to be an important factor in Breckinridge’s growing disenchantment with his General in-chief. For the moment, he decided that shuffling the military chain of command would be more demoralizing than anything, and he thought that the defense-oriented Johnston would be a good counterpart to the aggressive Beauregard. It’s obvious that Breckinridge underestimated the egos of both. Still, Breckinridge decided to focus for the moment on defending the Confederacy. Though losing Baltimore had been a tough hit, he recognized that it allowed them to retreat behind the more defensible Patapsco. He ordered his Generals to stand ready to defend against another Yankee attack during the autumn; after winter arrived, they could get a respite. In the meantime, Breckinridge would deal with the political and diplomatic ramifications of the war.

His counterpart at Philadelphia was also dealing with such matters. Now that he had taken back control of Baltimore, Lincoln set out to finally bring it under control. The President’s directive called for “a gentle, but firm and certain hand”, though he did concede that perhaps the government would have “to first employ the stick, and leave the carrot for later.” After Maryland seceded, Lincoln declared martial law and suspended the writ of habeas corpus, measures he now was able to enforce in Baltimore. Army officers and Maryland Unionists combed the city and its surrounding areas, not allowing evidence to stop their quest to stamp out treason. Many men were thrown into prison cells at Fort McHenry for supposed cooperation with the rebels. It’s not hard to suppose that many were innocent, and many did allege that the brief Confederate reign of terror had forced them to hide their true Unionist leanings, but some of the arrested men were people who had actively taken part on that reign.

Several of these men filled for writs of habeas corpus, thus starting a political and judicial battle against the Administration. Since the case was being held in Maryland, the petitions reached the senior judge of the Federal district court, Roger B. Taney. He and president Lincoln had been old enemies, and though the Head of State did not feel any personal animosity towards the Chief Justice, he had often and harshly criticized his decision in the Dred Scott case. Taney, for his part, detested Lincoln as a “vulgar abolitionist”, although he did respect Lincoln more than he respected other men, like Seward. Still, Taney actually refused to administer the oath of office; consequently, Lincoln was sworn in by Justice James Wayne, the second most senior member of the court (McLean, Lincoln’s vice-president and the most senior member, resigned shortly before the inauguration). Taney at least attended the ceremony, reportedly looking like a “galvanized corpse” the entire time. His constitution turned particularly ashen when Lincoln declared that the people couldn’t “resign their government into the hands” of judges.

Justice James Moore Wayne

Naturally, Taney issued the writs, but the officers refused, citing that: first, Maryland was under military government, and thus a civilian court couldn’t interfere; and second, Lincoln had suspended the writ. For Taney and the district court, he interrogatives were two: did Lincoln have the power to suspend the writ? And could a military administration be put in place in Maryland, even though Lincoln had recognized the legitimacy of the Frederick government? The writ, Taney said, could indeed be suspended “when in cases of rebellion or invasion the public safety may require it,” as detailed in Article 1, Section 9 of the Constitution. However, that provision is part of the article that details the powers of Congress. Thus, suspending the writ is an attribution of Congress, and the President couldn’t do it himself. Furthermore, the Constitution did not authorize the arrest of civilians by military officers, or them being held indefinitely. Lincoln simply ignored Taney’s opinion. "Are all the laws, but one to go unexecuted and the government itself go to pieces, lest that one be violated?”, he asked.

Pro-administration lawyers immediately took up the pen to defend the President’s policies. They argued that the suspension of the writ was intended as an emergency measure, that could only be taken by the President, especially when Congress was not in session. No matter Taney’s muddled arguments, its place in the constitution was irrelevant. Stopping treason was far more important, and since Maryland was a war theater, and its courts were probably compromised by treasonous civilians, using military courts was justified. Some even argued that since the act in question was treason against the nation, using American citizens was enough to fulfill the constitutional requirement to be judged by one’s peers. Others, not entirely comfortable with this argument, advanced the idea that treasonous individuals or people whose loyalty was suspect could not judge treason the same as a thief could not judge robbery. Consequently, the government had to use only Unionists in jury trials of suspected rebels.

Lincoln ignored these discussions of theory as mere abstractions, and instead focused on the very real threat of further rebellion in Baltimore. At least, it was real in some cases. People, who ranged from actual supporters of the Confederacy to lukewarm unionists, were rounded up first by army officers and later by Seward’s ruthless corps of military police. Despite being Secretary of State, Seward was tasked with internal security due to Lincoln’s distrust of Cameron. With rebels just behind the Patapsco, and McDowell unable or unwilling to launch an autumn campaign, Lincoln believed that he could not put Baltimore under the administration of the Frederick government. Many people were arrested. Among them were some of the Frederick government, secessionists elected to the original convention that remained there even after secession. Lincoln said that he had conclusive proof of their disloyalty, yet the government never indicted or tried them. Perhaps it was because the proof didn’t exist, but another reason was that the administration knew a Maryland jury would not convict them, and the Supreme Court hadn’t established whether military tribunals could be used.

Indeed, the case Ex parte Kane, named after Police Chief George Proctor Kane, was making its way through the judicial system. It reached the highest court in the land in 1863. Taney was joined by Justices Grier, Catron and Nelson in his opinion, which just reiterated what he had already said in the District Court: Lincoln had no authority to unilaterally suspend the writ, and could not try civilians in military courts if there were civilian courts available. Unhappily for Taney, Lincoln had been able to appoint as many as four Justices. He replaced Justice McLean, his vice-president; Justice Daniel, who had died in May 1860, the replacement appointed by Buchanan rejected by the Republicans; Justice Curtis, who had remained in the Court despite his disgust with the Dred Scott decision only at the bequest of McLean; and Justice Campbell, who had deflected to the Confederacy.

Noah Hayne Swayne, one of the new Lincoln-appointed Justices.

These four new Justices were strongly anti-slavery nationalists, who supported Lincoln’s efforts by declaring that the President could suspend the writ, but Congress would have to give its consent or disapproval as soon as possible. Since Congress had quickly given retroactive approval to all of Lincoln’s actions after convening in July, 1861, the President had acted legally. Moreover, Congress could authorize the use of military tribunals even in areas where civilian courts were working, if it was convinced that it was necessary for public safety.

This split left the balance on the hands of Justice Wayne. A Georgian, Wayne remained steadfast in his Unionism despite the scorn of his home state and the fact that his son had gone South to fight for the Confederacy. Decided to fight against treason no matter what, Wayne underwent a personal and professional transformation as a result of the war. The opinion of the Unionist Governor of Maryland Thomas Hicks in favor of suspending the writ and declaring martial law, helped Wayne arrive to his conclusion. He joined the 4 Lincoln Justices, and thus upheld the right of the President to declare Martial Law and receive Congress’ consent after the fact, and also the government’s right to create and use military tribunals to try treasonous civilians.

Earlier in the same year, another decision was reached regarding whether Lincoln had the ability to impose a blockade on the South without a formal declaration of war, the so-called Prize Cases. In a 6-3 decision, the Court declared that even without the Senate declaring war, Lincoln’s actions had been constitutional. The decision conformed to the President’s view of the war as an insurrection, and his absolute refusal to recognize the Confederacy as another nation. Yet declaring a blockade had implicitly recognized the Confederacy as a belligerent. The decision was also influenced by the actions of the rebel government.

Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles, nicknamed Father Neptune by Lincoln.

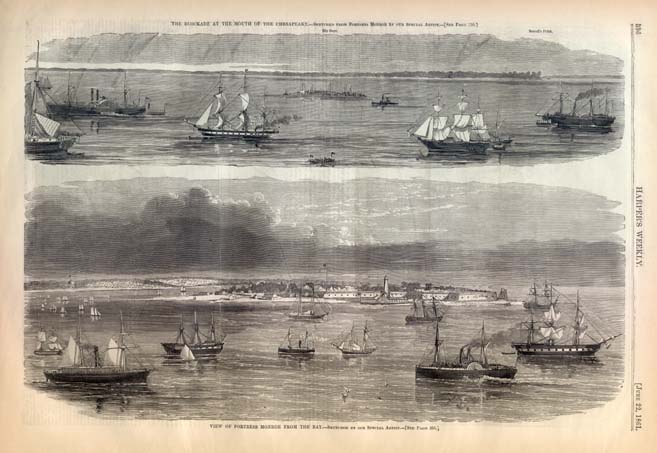

The Navy Department was little more prepared than the War Department had been, but it enjoyed advantages in leadership and existing resources, aside from the North’s usual industrial advantage. Gideon Welles and Gustavus V. Fox carried capable administration and dynamism respectively into the Navy. Soon, the Navy chartered or bought dozens of ships to supply the fewer than 12 they had at the start. They set off in the difficult task to blockade “the Confederacy's 3,500 miles of coastline” which “included ten major ports and another 180 inlets, bays, and river mouths navigable by smaller vessels” (McPherson, 369). Though the South could not hope to rival the North in material resources, Welles and Fox had their equals in Stephen R. Mallory, and commanders like Raphael Semmes and James D. Bulloch.

Mallory employed his country’s resources in small commerce raiders, and innovations such as mines or torpedo boats. At one point, the Confederacy even developed an experimental submarine. Bulloch was sent to Britain, where he managed to build several ships, and Mallory also approved the construction of an ironclad from the captured USS Merrimack. In the first months of the war, he focused on commerce raiding. President Breckinridge issued letters of marque to many privateers, who soon were roaming the oceans, capturing merchant ships and terrorizing shipowners.

Lincoln counterattacked by declaring these privateers to be pirates, and threatening to hang them as such. When a Philadelphia court convicted and hanged around 7 privateers, Breckinridge retaliated by executing 7 Union prisoners of war, including a grandson of Paul Revere. After that, Lincoln refused to continue such a bloody tic for tac, and directed the Navy to treat captured privateers as prisoners of war. The Confederacy had already changed strategy, shifting from privateering to commerce raiding. Here, Semmes achieved notoriety and infamy, guiding his CSS Beauregard into several victories over the Yankee blockaders.

These Union sailors faced exhausting monotony as often as they faced the rebels. Historian James M. McPherson estimated that blockade ships sighted a ship once every month or so, and took part in just one or two captures every year. However, when ships were sighted the emotion of the chase and the possibility of victory revitalized the sailors. Common sailors could earn as much as 3,500 USD if the ships they captured had particularly valuable prizes. On the other hand, blockade runners experienced these emotions and earned similar profits more often. The glory and adventure of running a blockade attracted scores, perhaps even hundreds of foreign officers, who wanted new and exciting experiences and also cherished the possibility of earning a profit without the danger of being held as prisoners. A British officer, for example, explained that "Hunting, pig-sticking, steeple-chasing, big-game hunting, polo—I have done a little of each— all have their thrilling moments, but none can approach running a blockade.”

Secretary Stephen R. Mallory

Both emotion and danger arose as the time passed and the blockade became stronger. To the Union’s system of two “cordons” and using light signals to converge on a spotted ship, the Confederacy answered by using specialized ships. Small, painted in grey and sailing only in foggy and dark nights, these ships were able to elude blockade runners. The Southerners’ home advantage also worked in their favor, for the captains knew “every inch of the coastline” and used this knowledge to scape the blockade and go to Habana, Nassau or Bermuda, where they interchanged cotton for salt, munitions, medicine, or clothes. Patriotism battled against pure greed here; many reserved their space for their own cotton or for luxury goods they then sold at auctions. Recognizing the extreme need for supplies, Breckinridge early on pushed for regulations that prohibited such goods and forced blockade runners to reserve half their space for the government. Naturally, it was hard to enforce. Richmond also commissioned its own ships.

Breckinridge and Confederate agents insisted that the blockade was nothing but a “paper blockade”, which other nations did not have to respect. Some 5 out of every 6 ships evaded the blockade successfully, and they brought in literals tons of war materiel. Yet, the Confederacy’s volume of trade was reduced to less than a third of its antebellum levels, and the people and army did feel its terrible effects. Mary Boykin Chesnut wrote, for instance, that the blockade “hems us in with only the sky open to us”; others complained that “every article of consumption particularly in the way of groceries are getting very high.”

Confederate blockade runners and Judicial challengers were enemies Lincoln and his persecution of war had, and they both did their best to hamper his efforts. The Administration's efforts to counterattack were mostly successful, but many of those policies were long-term ones that had to be followed throughout the entire war. In the autumn and winter of 1861, Lincoln also had to focus on the problems at hand, namely the rebel presence behind the Patapsco, and the rebel reaction in the West. The Maryland theater may have commanded the lion’s share of attention in the press and the public consciousness, but studying and understanding the development of the war in the west is also important. As McDowell settled down, his army too broken and inexperienced to act again in his opinion, the rebels launched attacks in Missouri, Kansas, and Kentucky, attacks which would highly influence the course of the war.