he was already born by the start of the civil warOr his father could take a bullet

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Until Every Drop of Blood Is Paid: A More Radical American Civil War

- Thread starter Red_Galiray

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 80 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 57: The Liberty Hosts Are Advancing! Appendix: Wikiboxes of US Elections 1854-1864 Chapter 58: Shall Be Paid by Another Drawn with the Sword Side-story: "A Baseball Legend" Side-story: "A deserter and a freeman." Epilogue: The Union Forever Bonus: Fun-facts and alternate scenarios Side-story: "A Story from Dr Da Costa"I read somewhere that WIlson happened to find himself looking straight up at Robert E. Lee and being so amazed once. So, he was at a very impressionable age.

What if he was separated from his family, in great danger... and a black man saves his life?

Actually, that's an interesting POD itself.

What if he was separated from his family, in great danger... and a black man saves his life?

Actually, that's an interesting POD itself.

Most people have absolutely how vicious a racist Wilson was. He personally segregated the civil service, firing most blacks in senior positions, and in at least one case a black office worker was enclosed in a "cage" type enclosure so that a white female worker passing by would not accidentally touch him. He was a supporter of the KKK, and in spite of being a respected academic touted "Birth of a Nation" as an accurate representation.

Ratshe was already born by the start of the civil war

Most people have absolutely how vicious a racist Wilson was. He personally segregated the civil service, firing most blacks in senior positions, and in at least one case a black office worker was enclosed in a "cage" type enclosure so that a white female worker passing by would not accidentally touch him. He was a supporter of the KKK, and in spite of being a respected academic touted "Birth of a Nation" as an accurate representation.

I have played with the notion of calling him the most racist president. Maybe in this timeline Teddy doesn't get as much flakk for eating with Booker? Gets re-elected and after him Taft? Maybe a harding presidency? I really do hope this TL goes beyond the Civil war...even if that means less detail per update post Civil War.

He's a Dixie carpetbagger who went to New Jersey.Most people have absolutely how vicious a racist Wilson was. He personally segregated the civil service, firing most blacks in senior positions, and in at least one case a black office worker was enclosed in a "cage" type enclosure so that a white female worker passing by would not accidentally touch him. He was a supporter of the KKK, and in spite of being a respected academic touted "Birth of a Nation" as an accurate representation.

What do people expect?

fdas

Banned

He's a Dixie carpetbagger who went to New Jersey.

What do people expect?

I think you have the wrong definition of carpetbagger.

Chapter 16: The Call of the Loyal, True and Brave

Chapter 16: We're Springing to the Call!

In August 1861, the Army of the Susquehanna set forth in its invasion of Confederate Maryland. 45,000 strong and led by the experienced Irvin McDowell, the Federals expected a glorious victory over Beauregard’s 30,000 rebels. They were emboldened by the success George B. McClellan had found in West Virginia a month earlier, and hoped to emulate and surpass it.

McClellan was a young and promising officer. Second in his West Point class, he had served in the Mexican War and then gone to a successful career as the President of a railway company. McClellan believed he was destined for great things, and accordingly carried himself in a Napoleonic manner, issuing declarations and dispatches in the style of the Little Corporal and even thrusting his right hand into his coat pocket for portraits, in imitation of the Frenchman. He did not feel that command of Ohio militiamen was enough for him, so he endeavored to travel to Harrisburg and assume command of the Pennsylvania volunteer regiments there, but stopped at Columbus by request of Governor Dennison.

Dennison was overwhelmed by the outpouring of patriotic fury that followed the Fall of Washington. Soon, he had more than twice the men Lincoln had requested, but he had no way of organizing or equipping them. The actual officers were unable to help him, and the politicians he appointed as commanders were not able either. Dennison decided to request help from a professional military man, in this case McClellan, who was living at Cincinnati at the time. McClellan prepared a careful report that foreshadowed his future tendencies for brilliant organization and cautious command. He advised Dennison to build up the defenses of Cincinnati, telling him that the only safe rule in war was “to decide what is the very worst thing that can happen to you and prepare to meet it.” Dennison was impressed by McClellan, and pleaded with him to assume command of Ohio’s troops as Major General. Expressing his “confidence that if a few weeks’ time for preparation were given he would be able to put the Ohio division into reasonable form for taking the field,” McClellan accepted.

McClellan quickly wrote dispatches to Philadelphia, asking for materiel and for Scott to place some officers under his command, such as Fitz John Porter. General Scott could not afford McClellan much equipment, due to the chaos that dominated the War Department and the need to supply the Army of the Susquehanna first, but he complied with McClellan’s request for officers. Porter was joined by officers Cox and Rosecrans, and together they set out to make an army out of the mobs that had gathered in Columbus. McClellan gave instructions for the construction of a camp, which he baptized Camp Dennison, and then started to drill his men, instilling discipline and pride in them. By his second week, journalists were already saying that they had never seen “more orderly soldiers, than those at Camp Dennison.”

George B. McClellan

While McClellan trained his troops, an activity he found very enjoyable, Lincoln, his cabinet, and General Scott were all debating how to form a rational war policy. Scott believed that a hard war would be disastrous, for the South would resist it to the last man. Scott warned that attacking would hurt the Union cause more than help it. He started to formulate what would come to be known as the Anaconda Plan. Under this plan, the Navy would blockade the Southern coast, while the Army would advance down the Mississippi and cut the Confederacy in half, thus surrounding the rebels on all sides. “Cut off from the luxuries to which the people are accustomed; and . . . not having been exasperated by attacks made on them,” the Confederates would come back into the folds of the Union, without the massive societal, economic and material destruction a prolonged war would have brought. McClellan, who was keeping a close eye in Kentucky and West Virginia, favored this approach for the time being, even if he advised more decisive action to aid the Unionists of those territories. McClellan’s ability was praised by Scott, and he also obtained the confidence of Secretary Chase, who played a part in McClellan’s appointment as commander of the Department of the Ohio. McClellan expressed his gratitude towards “the General under whom I first learned the art of war,” even as he grew frustrated with Philadelphia’s inability to supply his army.

When the Wheeling Convention proclaimed the new state of Kanawha, it became necessary to intercept the rebel advance towards the important rail junction at Grafton. McClellan and his worthy Army of the Ohio were up to the task. The Ohio and Baltimore Railway passed through Grafton, and though the Southerners at Harpers Ferry had already cut that railway, the Union expected to take back the Armory and then reestablish the line. More importantly, there were political considerations regarding the Kanawhean Unionists. They were already complaining that the Union had left them alone with the Secessionist wolves; since Lincoln firmly believed that a Unionist majority existed in the South, and because he wanted to cultivate such sentiments in Kentucky and Tennessee, coming to their aid was a priority. The 3,000 Confederates at Grafton entrenched themselves against the attack of 6,000 Federals. The outnumbered rebels decided to flee instead of face battle, and the Federals pursued through pouring rain and mud roads, an event gained the derisive name of the “Philippi races.” After this, both main commanders arrived at the scene.

The first was McClellan, who met his men at Grafton in late June. He issued a Napoleonic address: “Soldiers! I have heard that there was danger here. I have come to place myself at your head and to share it with you. I fear now but one thing—that you will not find foemen worthy of your steel.” Opposite of him was the Virginian Robert E. Lee. A refined and educated gentleman who came from one of the First Families of Virginia, Lee was characterized by a sense of dignity and duty that compelled him to take arms in defense of his state and family. After Virginia’s secession, Lee had resigned from the Army and accepted command of Virginia’s forces. After organizing them, he was sent to Annapolis, where he tried to dislodge General Butler’s forces. Lee’s attempt failed, and his subsequent emphasis on building fortifications earned him the disparaging nickname of “King of Spades.” Know he was sent to retake control of West Virginia, but the men at his disposal were not worthy of McClellan’s steel. Robert S. Garnett, the commander at Beverly, said that they were “in a most miserable condition as to arms, clothing, equipment, and discipline.” Indeed, most of the men lacked equipment and uniforms, using instead old homespun clothes and smoothbore rifles. A third of them were in the sick list.

Still, by late July Lee had managed to scrape together some 20,000 men, almost equal to McClellan’s 25,000. Lee’s reinforcements arrived in the nick of time, saving Garnett from an attack by Rosecrans in his flank. McClellan had decided against attacking Garnett’s trenched head on, confiding in Rosecrans flank maneuver; he would then exploit whatever weakness arose. Rosecrans managed to successfully turn up the rebel flank, but McClellan hesitated, and Lee exploited this. He drove back Rosecrans and then attacked McClellan. But his complicated scheme was fumbled by the inexperienced generals and sick soldiers. McClellan, for his part, panicked and started to talk of overwhelming Confederate numbers in the Alleghany passes. For a moment it seemed that the Confederates would succeed, but Lee's officers again failed him, and Rosecrans successfully counterattacked. Bickering between John B. Floyd and Henry A. Wise, two political generals who effectively hated each other, didn’t help the Confederates. An advance by them against Cox ended in disaster.

Soon enough Rosecrans tried another flanking attack, with the help of a Unionist man who led his troops through the difficult terrain. The rebels were routed and had to flee south, abandoning most of the mountain passes. By the time Lee had managed to take back control, supply problems and the stronger Federal position meant that there was no chance of counterattack, and he finally decided to give up, evacuating Kanawha, and yielding control of the Alleghany passes to the Union. Lee’s forces had not suffered many casualties, but they were incapable of launching any kind of attack, instead remaining in the Kanawha Valley. Consequently, Kanawha was effectively free of Southern troops.

John B. Floyd

McClellan was quick to claim this as a great victory, and newspapers anxious for success backed him up, even calling him the Young Napoleon. “Soldiers of the Army of the Ohio! . . . You have annihilated two armies, and defeated our foe in combat,” he proclaimed, “I have confidence in you, and I trust you have learned to confide in me.” For his part, Lee suffered the disappointment of his people, who added “Granny Lee” and “Evacuating Lee” to their repertoire of insults. Breckinridge himself couldn’t hide certain disappointment, because he and many others had expected great things of Lee. The Virginian was sent South to defend South Carolina, Beauregard’s old post, and while the Conqueror of Washington was still being hailed and exulted by the newspapers, Lee was declared to have been “outwitted, outmaneuvered, and outgeneraled.” Rosecrans failure to drive the rebels out of the Kanawha Valley (an area of strong pro-Confederate sentiment) did nothing to eclipse McClellan’s laurels.

The victory allowed Kanawha to establish itself as a true state, and ask for admission to Congress. The Republicans however were unwilling to admit the state unless it abolished Slavery first. The convention voted to enact a plan for gradual emancipation in early 1862, but by then aptitudes and policies regarding slavery had been evolving. Kanawha, together with Kansas, became models for future Reconstruction plans, and radicals in Congress felt the need to take a stronger stand against slavery. Kanawha was admitted as a state in 1863 after it approved a constitution that effectively emancipated all slaves. At the same time, Kanawha suffered from the consequences of internecine warfare, which devastated the areas around the Valley and led to brutal counterinsurgency policies by the Union.

The Confederacy also was forced to adopt anti-insurgent measures, mainly in East Tennessee and Texas. In the first, strong Unionist sentiment was harnessed by Senator Andrew Johnson and William G. Brownlow, a Methodist preacher who vowed to fight secession and treason “till Hell freezes over, and then fight them on the ice.” But bad terrain and lack of roads prevented action, much to Lincoln’s chagrin. Unionist attempts to form militias and resist Confederate authority resulted in the proclamation of martial law and the execution of several Unionists. Down in Texas, German settlers rallied to the Union banner. Many important leaders, including Sam Houston, opposed secession. Houston, in fact, had been removed by the Legislature due to his refusal to pledge allegiance to the Confederacy. Many Unionists would suffer under Confederate rule, even to the point of being massacred for their pro-Union activities.

However, the eyes of the nation were in Maryland. McDowell planned to advance along the Philadelphia-Wilmington Railroad towards Baltimore, and attack the city from the North. Union control of Fort McHenry would trap the Confederates in the city. He would follow this with an attack on Beauregard across the Patapsco. Meanwhile, Patterson would make a feint against the Confederates near Frederick. Should the rebels be sent to aid Beauregard, Patterson was to start a real attack and drive his forces towards Rockville. If the Southerners at the Rolling Hills were withdrawn, or Beauregard was successfully occupied by McDowell, Butler would then stage a breakthrough and go north to Beauregard’s rear. If successful, the attack would encircle the Army of Maryland and force the remaining Confederates to evacuate.

Irvin McDowell

But McDowell’s plan was marred by inefficiency and the inadequacy of his “green troops.” Though Lincoln assured his general that the Confederates were just as green, the fact was that they enjoyed a psychological edge over the Federals because of the Fall of Washington. Furthermore, in the time it took to build an army, Beauregard had built strong defenses in the Patapsco, and the Federals had little idea of the strength or extension of these fortifications. Still, McDowell attacked in August 14th, 1861, a flurry of reporters and onlookers behind him.

His army advanced to the outside of Baltimore, where they found Beauregard’s men in a small stream known as Herrings Run. To the North, Confederate artillery and infantry was placed at Townstown, near where two railroad tracks met. In the west, the first great failure of the campaign took place. Patterson, confused by diverging orders from Philadelphia and McDowell, just maneuvered in front of Jackson’s Brigade, and never launched an attack or took any part in the rest of the campaign. Realizing his chance, Johnston ordered Jackson to Annapolis, where the impatient Butler had launched an attack before McDowell had started his. Jackson, an eccentric man who combined strict discipline with a profound faith and used both to push his men to the limit, had acquired certain fame and respect during the Siege of Washington, but it was in Annapolis that he became a legend. Arriving at the last minute, his brigade resisted the attack. Butler’s own mismanagement can also be blamed, for the political general had talent as an administrator and politician but not as a military commander. Still, Jackson’s staunch resistance against Butler’s attacks earned him his famous nickname – Stonewall Jackson.

The Federals found greater success around Baltimore. There were mainly two paths: a road to Baltimore and the railroad to the South. The rebels had, of course, cut off the railroad, but it still served as an easy venue of invasion. McDowell decided to make feints through both paths. When Colonel Evans noticed the feint against the Northern road, he took his 6,000 rebels there, and slugged it out against 10,000 Union soldiers. In the meantime, McDowell directed his men to the railroad bridge. They forded the river and attacked the rebels north of them, forcing Evans to retreat. The river crossing, however, had been fumbled and McDowell was unable to bring out his full force against Beauregard. Still, the onlookers were feeling joyful, and too optimistic reports were reaching Philadelphia talking of great victory and the total defeat of Beauregard’s forces.

Thomas "Stonewall" Jackson

For hours, exhausted Federals pushed against the Confederates, who suffered from the same lack of munitions, equipment and medicine that brought down Lee’s campaign. Finally, the Confederate line broke and scared soldiers started to retreat towards Baltimore. While a steady flow of Union reinforcements was arriving, even if slowly, there were no Confederate reinforcements to be seen. They were either North, where William T. Sherman’s regiment was able to pin then in their place, or behind the Patapsco, kept there by Johnston who was not willing to commit the whole of his force to the battle. Johnston’s cautious demeanor was in clear display here, and like McClellan’s actions in Kanawha, it was a preview of things to come. Johnston would rather take the safe route of waiting until the bluebacks reached the river, where any attack would come to grief. Moreover, there was still the possibility of Butler breaking out of Annapolis, and Johnston wanted to be able to reinforce Jackson if that happened, because a successful breakthrough would put a large Union force in Beauregard’s rear. Johnston’s actions were sound in theory, and lack of communications and the inexperience of his officers meant that he did not know that Jackson had successfully contained Butler, or how disorganized Beauregard’s men were. Nonetheless, Beauregard hotly contested the decision and sent increasingly irate demands for more men. When they were answered, the rebels were already retreating in a disastrous rout.

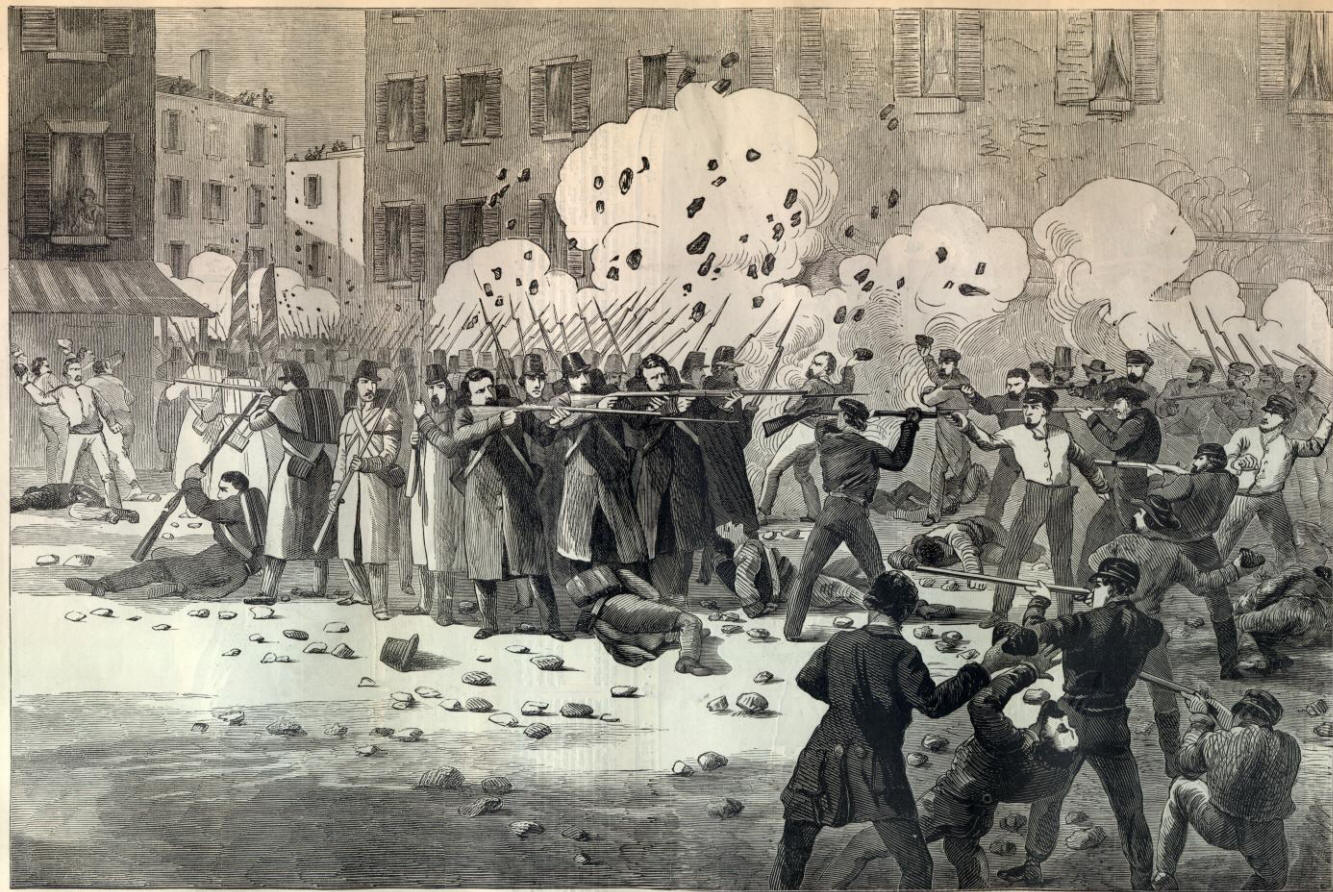

McDowell was astonished by his success. Discipline and morale were starting to crumble behind the frontlines, so he was unable to completely capitalize in this victory. Still, he was excited and ordered the men in Fort McHenry to go forward into the city in August 15th, expecting the final showdown to take place there. But a strange spectacle took place, as many Confederates ignored Baltimore, flanking it and going directly to the Patapsco. Baltimore, in their minds, was a dead trap that would end with them surrounded and sieged. Union supremacy at seas and especially the imposing Fort McHenry would ensure eventual defeat. Others were decided to fight to the end, and entered Baltimore to face the Marines and other troops that were now marching towards Federal Hill. In scenes of pitched urban fighting like none the world had ever seen, militia, soldiers and even citizens resisted with everything they had, making the Federals pay every step with liters of blood.

The soldiers were ill-equipped to fight like that, and most of them found themselves lost in the sprawling city. But they received help from an unlikely source: The Black community of Baltimore. The few months under Confederate control had been an effective terror reign over them. There are many tales of Free Blacks being chained and hauled down South, for even the mere existence of a Free Black community was a threat to the White Supremacy the South championed. This abnormality had to be corrected, and as a result many suffered under the hands of Confederates. The Union was seen as a Liberating Army, and with Baltimore descending into chaos, concerns regarding race were forgotten in the heat of battle. It helped that the soldiers who assaulted Baltimore that day were from some of the most Republican states, such as Massachusetts. They were committed men who wanted to exterminate treason and slavery, “in the most literal sense.” Fighting between pro-Confederate and pro-Union mobs was bloody and brutal, but by the end of the day the Federals had the clear upper hand over the exhausted Southerners, most of whom had been fighting since the previous day. Naval support proved to a key to victory, the cannons of nearby Union ships destroying large sections of the city and maiming the Confederates. At sunset, the Union soldiers achieved their objective, taking the Federal Hill in a charge of fixed bayonets that broke the defenders.

Battle of Baltimore

While these bloody and appalling scenes were taking place in the city, McDowell pursued his foes. Now that Butler’s failure was clear, Beauregard had finally received reinforcements and he had gone to the frontlines to rally his troops to battle. He also received the troops that Sherman had pinned at Townstown. For his part, Sherman’s mostly fresh men joined McDowell. By that time, forced marches and sheer exhaustion had caused thousands to simply drop to the ground. Realizing that he couldn’t keep up this pace, and confident that the Confederates were almost beaten, McDowell set down behind a stream called Gwinn’s Falls. But suddenly a chilling scream came from the other side of the river, an “unearthly wail” that filled the Northern hearts with dread. "The peculiar corkscrew sensation that it sends down your backbone under these circumstances can never be told. You have to feel it," said a veteran after the war. Thousands of rebels went forward, led personally by Beauregard. The tired Union soldiers were unable to do much, with the exception of Sherman’s brigade. The Union line broke, and the Federal soldiers simply threw their arms away and ran to Baltimore in a frantic display. Some officers even made better time than their men.

After that, it was all anti-climax. Beauregard was unable to press this victory; McDowell could not retake control of his men nor did he have any other reserves. Thousands of wounded and agonizing rebels fled Baltimore, followed by pro-Confederate citizens who feared the wrath of the Black Republicans and their Negro mobs. The Federals returned to the city, which had finally calmed down by the 16th. They had achieved a victory, but it came at a high cost.

Battle of Herrings Run

The cost of the Baltimore campaign was indeed high. McDowell himself was sickened and appalled by the fighting and its brutality. The two days of fighting had seen three different but equally terrible battles; the Union had won the Battle of Baltimore and the Battle of Herrings Run, but lost the Battle of Gwinn’s Run. More than that, they had lost almost a 1000 dead and 2000 wounded. The Southerners, for their part, had lost 1300 dead, 1500 wounded and 1200 captured. More than that, the Baltimore campaign set the pace for the war that was to come, a cruel and terrible war that would leave many more men dead. For the moment, the Union could at least rejoice in its victory over the Southern forces and the successful capture of Baltimore, a hit that tarnished the reputation and prestige of the Confederate government. But Washington was still in the hands of the enemy. It was becoming increasingly clear that this was not going to be a limited and short war, but a fiery and difficult struggle. The reports of the battle may have horrified both Lincoln and Breckinridge, but the guerrillas that swarmed in Kansas, Missouri and Kentucky; the guerrillas that were rallying in Kanawha, East Tennessee and Texas; and the savage fighting at Baltimore and throughout Maryland; all pointed that the worse was yet to come.

Last edited:

If you create a timeline where popular history exults the brilliant McClellan and denigrates the apathetic Lee (while academics vainly try and stand up for complexity) I'll be very amused.

Ouch, that was certainly more brutal fighting than OTL saw that early in the war. And it sounds like it is going to get worse.

Now that Baltimore is wrapped up, will we get a map showing the front lines across the union?

Now that Baltimore is wrapped up, will we get a map showing the front lines across the union?

Both sides had more faith in "pro" forces in "enemy" states than justified, however Union "pros" were more numerous than Confederate "pros". Some areas will have bushwhackers of both sorts, but as regular forces become more numerous and better organized they will be more annoying than anything else. I would expect with the treatment of free blacks in Baltimore and the strong pro-Union response of the blacks, we may see black Union troops sooner.

The Battle of Baltimore is really setting the scene for this more extreme Civil War. The results on American military tradition will be interesting.

BP Booker

Banned

I was hoping West Virginia would remain part of Virginia with the Unionist there acting as a sort-of Taiwan "We are the real Virginia" analog but I guess it was not meant to be

The US will be exhausted after the dust settles

Those are some pretty dire statistics. Not "the Union is going to lose" numbers, but definitely "its not gonna be easy" numbers.More than that, [the Union] had lost almost a 1000 dead and 2000 wounded. The Southerners, for their part, had lost 1300 dead, 1500 wounded and 1200 captured.

The US will be exhausted after the dust settles

why do I feel like your hinting at something by having Lee go to South Carolina

Well with West Virginia taken and a reorganization of forces there I bet little Napoleon will try to convince union command that they should invade through the valley

The reason why casualties are so high is

that they sort of fighting on the enemy hone turf and that they are incredible green and as time go on once these troops harden the advantage for the union will compound

Well with West Virginia taken and a reorganization of forces there I bet little Napoleon will try to convince union command that they should invade through the valley

The reason why casualties are so high is

that they sort of fighting on the enemy hone turf and that they are incredible green and as time go on once these troops harden the advantage for the union will compound

Towson?Townstown? That's the worst name I've ever heard.

With a death toll over twice that of our timelines first Bull Run, there is definitely more than hint of a much worse War.

Still, unlike first Bull Run, there is part that is a clear Union victory. This will be encouraging to a lot of people, especially with a city as big as Baltimore.

It looks like Rosecrans will also get quite a bit of a promotion out of this also, even if McClellan is she has the winner he will definitely have had a big part of it.

Still, unlike first Bull Run, there is part that is a clear Union victory. This will be encouraging to a lot of people, especially with a city as big as Baltimore.

It looks like Rosecrans will also get quite a bit of a promotion out of this also, even if McClellan is she has the winner he will definitely have had a big part of it.

Used to live in Baltimore...that should be Towson - just north of Baltimore

Very disappointed that Townstown is not a real name.

That is beautiful work. Richly detailed and fascinating.

McClellan always was fantastic at drilling troops. Lincoln should appoint him "Marshal of Discipline" or something and put him in charge of training troops to send to the front, then put someone more aggressive or with better tactical skills in charge of the field forces.

Lee being sent to South Carolina--are you trying to make the South collapse in a month? Lee was the only half-decent general the South had!

Good to see that West Virginia/Kanawha is being supported and that Union troops are becoming more racially tolerant earlier. Hope to see black troops by the end of the year!

Keep up the good work!

McClellan always was fantastic at drilling troops. Lincoln should appoint him "Marshal of Discipline" or something and put him in charge of training troops to send to the front, then put someone more aggressive or with better tactical skills in charge of the field forces.

Lee being sent to South Carolina--are you trying to make the South collapse in a month? Lee was the only half-decent general the South had!

Good to see that West Virginia/Kanawha is being supported and that Union troops are becoming more racially tolerant earlier. Hope to see black troops by the end of the year!

Keep up the good work!

Threadmarks

View all 80 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 57: The Liberty Hosts Are Advancing! Appendix: Wikiboxes of US Elections 1854-1864 Chapter 58: Shall Be Paid by Another Drawn with the Sword Side-story: "A Baseball Legend" Side-story: "A deserter and a freeman." Epilogue: The Union Forever Bonus: Fun-facts and alternate scenarios Side-story: "A Story from Dr Da Costa"

Share: