It would work simply as an instrumental without lyrics also, perhaps something like that is included with some of the things John Philip Sousa wrote, and become Incorporated in those Grand Finale fireworks productions which end with the 1812 Overture and all those cannons. ( I have no idea what you call that, obviously it's not a single song, I don't know if concert is the right word. But you all got the picture in your mind at least.)

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Until Every Drop of Blood Is Paid: A More Radical American Civil War

- Thread starter Red_Galiray

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 80 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 57: The Liberty Hosts Are Advancing! Appendix: Wikiboxes of US Elections 1854-1864 Chapter 58: Shall Be Paid by Another Drawn with the Sword Side-story: "A Baseball Legend" Side-story: "A deserter and a freeman." Epilogue: The Union Forever Bonus: Fun-facts and alternate scenarios Side-story: "A Story from Dr Da Costa"it's more I can imagine the stanzas being swapped around due to personal preference and/situationIt would work simply as an instrumental without lyrics also, perhaps something like that is included with some of the things John Philip Sousa wrote, and become Incorporated in those Grand Finale fireworks productions which end with the 1812 Overture and all those cannons. ( I have no idea what you call that, obviously it's not a single song, I don't know if concert is the right word. But you all got the picture in your mind at least.)

Something I'm morbidly curious about is how the future Sherman meme reddit page would be like. Like roasting Confederates is the national pastime there. Like I wonder what memes will this TTL war spawn.

Or radical fire-eaters, for that matter.Hang vicous, hands on war criminals (William Quantrill and the like)

Prosecuting them for saying horrible things shouldnt fly, if only because you’d have to deal with the Northerners who were talking about exterminating the south and the like.Or radical fire-eaters, for that matter.

Unless they were elected officials, then they could be charged with sedition.Prosecuting them for saying horrible things shouldnt fly, if only because you’d have to deal with the Northerners who were talking about exterminating the south and the like.

Excerpt on Franklin Pierce:

After efforts to prevent the Civil War ended with the firing on Fort Sumter, Northern Democrats, including Douglas, endorsed Lincoln's plan to bring the Southern states back into the fold by force. Pierce wanted to avoid war at all costs, and wrote to Van Buren, proposing an assembly of former U.S. presidents to resolve the issue, but this suggestion was not acted on. "I will never justify, sustain or in any way or to any extent uphold this cruel, heartless, aimless, unnecessary war," Pierce wrote to his wife.[152] Pierce publicly opposed President Lincoln's order suspending the writ of habeas corpus, arguing that even in a time of war, the country should not abandon its protection of civil liberties. This stand won him admirers with the emerging Northern Peace Democrats, but others saw the stand as further evidence of Pierce's southern bias.[153]

In September 1861, Pierce traveled to Michigan, visiting his former Interior Secretary, McClelland, former senator Cass, and others. A Detroit bookseller, J. A. Roys, sent a letter to Lincoln's Secretary of State, William H. Seward, accusing the former president of meeting with disloyal people, and saying he had heard there was a plot to overthrow the government and establish Pierce as president. Later that month, the pro-administration Detroit Tribune printed an item calling Pierce "a prowling traitor spy", and intimating that he was a member of the pro-Confederate Knights of the Golden Circle. No such conspiracy existed, but a Pierce supporter, Guy S. Hopkins, sent to the Tribune a letter purporting to be from a member of the Knights of the Golden Circle, indicating that "President P." was part of a plot against the Union.[154][155] Hopkins intended for the Tribune to make the charges public, at which point Hopkins would admit authorship, thus making the Tribune editors seem overly partisan and gullible. Instead, the Tribune editors forwarded the Hopkins letter to government officials. Seward then ordered the arrest of possible "traitors" in Michigan, which included Hopkins. Hopkins confessed authorship of the letter and admitted the hoax, but despite this, Seward wrote to Pierce demanding to know if the charges were true. Pierce denied them, and Seward hastily backtracked. Later, Republican newspapers printed the Hopkins letter in spite of his admission that it was a hoax, and Pierce decided that he needed to clear his name publicly. When Seward refused to make their correspondence public, Pierce publicized his outrage by having a Senate ally, California's Milton Latham, read the letters between Seward and Pierce into the Congressional record, to the administration's embarrassment

So, I recently had Franklin Pierce brought to my attention, as I had no idea how politically active the man was after his presidency. I, like most people, tend to overlook most of the mid 19th Century Presidents as un-unique and forgettable.

And in challenging a bit of my historical ignorance, I found out that Pierce was considered a security threat by the Lincoln administration. He criticized the president for suspending Habeas corpus and was absolutely opposed to the war.

The man turned down running in 1860 and spent his post-presidency traveling and commenting on the growing tensions in the US, saying " that the bloodshed of a civil war would not be along Mason and Dixon's line merely but within our own borders in our own streets".

When Jefferson Davis' plantation was captured in the war, he had letters with him predicting " that civil war would result in insurrection in the North." All of this was sent to the press and of course made him very unpopular with the growing abolitionist movement in the North.

His wife died in 1863, his closest friend Nathaniel Hawthorne died the following year.

His instincts tended to push him away from direct participation in electoral politics and drinking damaged his health in later years. He turned to religion as he grew closer to death and spent his leftover connections and resources to get better treatment for Jefferson Davis while he was in prison and supporting relatives.

I wrote all of this to say that Pierce is an interesting character and I think that this TL could have some use of Franklin Pierce if @Red_Galiray so wishes.

IOTL, he was largely disgraced during the war and the sections of the country he most represented were firmly in Republican hands or under reconstruction by the time he died.

But, if there were ever a person that the terrorized Chestnuts and disaffected conservatives, and unconverted old Whigs could coalesce around, I think Franklin Pierce might work. He was considered a potential compromise candidate in 1860, and after a chaotic and exhausting war, brigandry in the countryside, abolitionism not only ascendant but with broad public buy-in, I think a man like Pierce might take a quixotic stand if only because there would no longer be any good options left.

This version of the United States has seen a far greater degree of change and pain than OTL. Radical change breeds reactionaries. As disunited as the various political actors are at the moment and as strong as the Republican Party is, there is always room for strange occurrences and upsets, even if they are ultimately defeated.

During Reconstruction there were stranger events than an already proven President running for a second term well past his prime. Sure, he'd be considered a closeted traitor, but so is everyone else that isn't a registered Republican.

With the level of political disruption that's happened so far, it could be interpreted to have gone so far as to RE-legitimize someone like Pierce, in some political circles:

"The Man Who Would Have Stopped the Slaughter"

"The Intelligent Friend of the True American"

Having abolitionism become mainstream only retrenches the ideas that the fight against the Black Republicans was always just and necessary for those who aren't converted, because the upheaval they are going through will be seen as having been intentional. To many, the Republicans are a party of John Browns, using the Federal government to arm slaves and kill principled and decent Americans.

Societies under stress are always susceptible to conspiracy theories and with all the developments taking place throughout the country, from the purging of the Chestnuts to everything concerning Freedmen, another national myth could take the place of the OTL Lost Cause and spread throughout the country as well; something about a Radical Republican Plot to take over the government to arm negroes and destroy the south.

The myth might not survive the 19th century, but it could put some wind in the sails of a last hurrah for the Antebellum America that will never be convinced that all this death and destruction was ever worth it.

If you keep his wife alive and get a quicker admittance of some of the Southern States and suitably discredit/split the Republican Party enough to make the race competitive, then we could have a very interesting election down the line.

Even if being anti-war is unpopular now, once the fighting stops and the country has to reflect on everything that's happened, there will be some renewed resistance to further upsets like amendments or land reform.

A Pierce/Pendleton ticket has a certain ring to it, no?

Edit: I think that the mixture of genuine social disruption, the vindication of the war occurring exactly in the way Pierce and the political class he represents always feared it would, and the lack of an otherwise respectable unifying figure lends to Pierce at least being a name in circulation. He's one of few people left with any national regard from the old party system.

Between his potential presidential runs, the failed urge for all the former presidents to call for a constitutional convention, and the continuous speaking tours after his presidency, Pierce seems like a man who often failed to truly commit to bold action on account of other people's inaction/actions, being ruled by other people's choices.

But with the field clear and the country in the hands of Radical Republicans, it seems fitting for Pierce to go for broke so late in his life, long after it could have actually made a difference.

That seems fit for a tragedy if there ever was one.

An aside:

I also looked into Millard Fillmore a bit, he's also an interesting character post-presidency. But I don't he'd have the necessary clout or standing to run for president again. He's not in the right circles. He's too close to the opposition to ever be supported by Republicans and too involved with Republicans to be trusted by the opposition.

Last edited:

Davis was extreme delussional IOTL. I wonder how Breckinridge handle it? He may have less illussions, but he has to expect the total dismantiling of the old southern order. So he see a fight till the end as only option.

There's always a possibility that by the war's end, the decision won't be in Breckinridge's hands at all. An even tempered man is going to butt heads with his generals the worse the war goes. And if Breckinridge negotiates terms that don't guarantee the safety of those generals, all of whom I'd assume are at least implicated in warcrimes, the possibility for a coup comes into play.Breckenridge is anything but a bitter-ender. If he believes the war is hopeless, he is likely to be like Stephens and Campbell - that is, try and end the war in a conditional peace that may yet retain at least some of the South's political and economic power. The question is, would that be possible?

That would only hasten their defeat, but if they're dead men anyway (or assume they will be on account of Lincoln's terrible reputation) every day they're still alive is a day they can either keep fighting or plot an escape from the country.

Civilian governments are never safe from their militaries, not truly.

Hey, here's a random thought to hopefully spark some discussion: what will be the result of the treason trials? Because there will be some treason trials, mostly for the most prominent Confederates who didn't manage to get away. Say, Stephens is captured and put on trial, and he argues that he couldn't have committed treason because he forfeited his US citizenship upon joining the rebellion.

Took the words out of my mouth.Lincoln will probably commute most of the sentences to prison or the like

I expect anything approaching justice for the Confederate leadership will be moderated or commuted by Lincoln, especially if the Congress/Generals? go for blood.

There is also something to be said about the Confederate dealings with foreign powers for purposes of building a navy or outfitting their army or just seeking diplomatic recognition. These are all interference with US sovereignty and facilitate a continued insurrection against the United States.I think anyone with a legal background here would be best suited for answering @Red_Galiray on the matter of treason. But my personal impression in crime is that intent and planning are one of the biggest factors in criminal cases.

In regards to Breckenridge trying to broker a peace IIRC it's been hinted that he's not president or at least calling the shots by the time the war ends. That along with the hints that imply at least one big name Confederate general(coughLongstreetcough) defects back to the Union indicate by wars end the Confederacy is under their equivalent of the officer clique that tried to keep Japan fighting after the Emperor decided to surrender.

Regarding Pierce, I see him more as the candidate for 1868. In 1864, the real opposition will be the more radical one than Lincoln, maybe Fremont. But in 1868, this Civil War is so much worse that someone like Horatio Seymour, who didn't even want the nomination in our timeline, will not be able to run efficiently. However, while the Democrats are gone as a force, that Coalition you mentioned will be there and it will be easy for Pierce to say that, "now that what's done is done as far as the war is concerned, let's not continue the war throughout the peace, let's get back to a more stable country like we once were."

That would have some appeal and might win him a few States. It would also be even more like Don Quixote tilting at windmills, and yet might earn him some sympathy votes as an old man who just doesn't understand anything that happened after his presidency. Perhaps it will be seen that his son dying was the start of an incredible downfall in his mental state. One that resulted in his not even understanding there was a problem.

This timeline's Turtledove would not write of timeline 191, no there would be no place for the possibility of a Confederate victory. It would be seen as evil as a Nazi one. There would however be the possibility of a Pierce timeline where the Point of Departure is his son surviving and there goes on to be this warm and happy piece where slavery is ended through gradual emancipation and people are convinced not to fight.

I mean, sure it's unrealistic. But... Aliens invading in 1942 and all that? Hey at least he'd be going the Star Trek route here, with Pierce in the role of Captain Kirk saying "slavery... Is wrong... You need as a society... To come to a conclusion to end it.... Or you are all... going to face horrible consequences."

That would have some appeal and might win him a few States. It would also be even more like Don Quixote tilting at windmills, and yet might earn him some sympathy votes as an old man who just doesn't understand anything that happened after his presidency. Perhaps it will be seen that his son dying was the start of an incredible downfall in his mental state. One that resulted in his not even understanding there was a problem.

This timeline's Turtledove would not write of timeline 191, no there would be no place for the possibility of a Confederate victory. It would be seen as evil as a Nazi one. There would however be the possibility of a Pierce timeline where the Point of Departure is his son surviving and there goes on to be this warm and happy piece where slavery is ended through gradual emancipation and people are convinced not to fight.

I mean, sure it's unrealistic. But... Aliens invading in 1942 and all that? Hey at least he'd be going the Star Trek route here, with Pierce in the role of Captain Kirk saying "slavery... Is wrong... You need as a society... To come to a conclusion to end it.... Or you are all... going to face horrible consequences."

Well that's the thing, I put Pierce forward as a kind of tone-deaf farce of a run rather than as a genuine threat.I see him more as the candidate for 1868. In 1864, the real opposition will be the more radical one than Lincoln,

Red has made it clear that the Republicans are going to dominate for the next generation in some form, so having Franklin Pierce of all people having a good showing in the 1860s contradicts that. I still think that could be quixotic in its own way.

It's like charging at a burning barn to save the dry straw. What for? No one sane could ever guess. (You won't save the straw, you'll only get burned)

But also, he's just too old by 1868. I'm sure keeping his wife alive could keep him more energetic and well balanced while he's alive and probably give him a few extra years. But it wasn't grief alone that killed him, it was drink. 6 years is a long time to be a widower if heartbreak is actually what killed you.

To me, that adds to the hopelessness of it all. He's not bold enough, he's not popular enough, and when his time really comes he's not even young enough.

Last edited:

But... he's written Nazi victory scenarios.This timeline's Turtledove would not write of timeline 191, no there would be no place for the possibility of a Confederate victory. It would be seen as evil as a Nazi one

Wow. You can tell I'm not a huge reader of AH books.But... he's written Nazi victory scenarios.

I figured the Democrats would be so dead by 1868 there would be just as little a chance of the GOP losing as 1864, but it's possible he could be seen as viable just by accident in 1868. Although, he was only in his mid-60s, which doesn't seem too old by today's standards but was ore so back then, it's true. (And after all that alcohol he probably had the body of an 80-yearold at least, and maybe the liver of a 100-year-old.)Well that's the thing, I put Pierce forward as a kind of tone-deaf farce of a run rather than as a genuine threat.

Red has made it clear that the Republicans are going to dominate for the next generation in some form, so having Franklin Pierce of all people having a good showing in the 1860s contradicts that. I still think that could be quixotic in its own way.

It's like charging at a burning barn to save the dry straw. What for? No one sane could ever guess. (You won't save the straw, you'll only get burned)

But also, he's just too old by 1868. I'm sure keeping his wife alive could keep him more energetic and well balanced while he's alive and probably give him a few extra years. But it wasn't grief alone that killed him, it was drink. 6 years is a long time to be a widower if heartbreak is actually what killed you.

To me, that adds to the hopelessness of it all. He's not bold enough, he's not popular enough, and when his time really comes he's not even young enough.

Our Intrepid storyteller is probably still bogged down with work, but I did think of something but is surprisingly not baseball.  it is entertainment, though, and sports and entertainment were the first two areas that black people were accepted into in white culture in our timeline. So, something like this in the last years of the 1800s is likely. And, in case anyone asks, yes it was going to be a simple joke about General Tso's chicken and a reply that if the general's chicken at least he isn't as bad as General McClellan...

it is entertainment, though, and sports and entertainment were the first two areas that black people were accepted into in white culture in our timeline. So, something like this in the last years of the 1800s is likely. And, in case anyone asks, yes it was going to be a simple joke about General Tso's chicken and a reply that if the general's chicken at least he isn't as bad as General McClellan...

Joe, a white man, and Abraham, a black man, are sitting at a table sheets of paper in front of them in a small hotel room in Cleveland.

"Okay, let's run through that last part of the last scene." Abraham picked up his tray, stood, and looked at Joe, who was staring at his fake meat. "What seems to be the problem?"

"My chicken just moved away from the sauce!" The man had used a magic trick to make it appear as though the item on his plate have moved.

"Well sir, it should have been obvious that it would flee anything in its path,, it is General McClellan's chicken."

Joe smiled. "Okay, perfect. I just wish we could be sure that joke we came up with wandering us would not earn us a blue card for being too risque, that one where I say at least I'm not as upset as my wife when she is in her minstrel cycle."

"I think it's been long enough that just calling him chicken is enough without having to discuss whether he was trying to lose, " Abraham replied.

"That's one reason I thought you would be best to mention the dish each time."

Abraham thought that it would be okay if Joe refer to it also. "However, I think the audience only to hear the name twice, once when I mention it as one of our newest dishes and once when I come back."

"Sure. You're sure you don't mind the last bit?"

"To be perfectly frank, I'm a little pleasantly surprised that you bother to be concerned," Abraham said.

"I know," Joe said. "But baseball teams are integrated in many places, and teammates seem to interact with them fairly well. I think this new Vaudeville has the same potential to bring people together."

"And, what our fathers went through during the Civil War definitely means we have become... friends, even. Not just business partners."

Joe agreed, after which he picked up a plate and threw a creampie in Abraham's face. Both began to laugh.

"And I know you'll find a way to give me a pie in the face too, later on. Once we have our little invention established," Joe said as Abraham wipe the pie off of his face.

"I'm sure I will," Abraham said with a smile as he finished wiping his face off. "There aren't a lot of areas yet where our races are consistently together. The dream our fathers had can live on, however. What they went through will not have to be in vain. Who knows how long it would have taken otherwise. It might be a long while yet till we are totally accepted as equals everywhere. But this can be a great beginning."

A few years later, the audience in that Cleveland Restaurant & Vaudeville Club laughed hard as Abraham gave Joe a pie in the face as a reward for some of the shenanigans Joe had done.

Backstage, James Garfield, now elderly in his 70s, shook both of their hands. "I have been following the two of you with great interest. I am glad I was able to move back here after my presidency."

There aren't a whole lot of other cities where this could be done. I'm glad we have a place like this, we have traveled to Pittsburgh and even played in Peoria," Abraham said.

""And, the greatest stage of all awaits you." The former President grinned. "My good friend is the father of your agent. And after all I have dealt with working to ensure that radical agenda of equality could come to pass as much as it could, I wanted to be the one to congratulate you. You got a booking in New York. Every night for two weeks."

The men gasped and shrieked with excitement as they looked at the contract former President Garfield showed them. Their dreams, and the dreams of so many, were coming true. They were only a small comedy duo in the grand scheme of things. But like many before, they were blazing a wonderful trail.

Joe, a white man, and Abraham, a black man, are sitting at a table sheets of paper in front of them in a small hotel room in Cleveland.

"Okay, let's run through that last part of the last scene." Abraham picked up his tray, stood, and looked at Joe, who was staring at his fake meat. "What seems to be the problem?"

"My chicken just moved away from the sauce!" The man had used a magic trick to make it appear as though the item on his plate have moved.

"Well sir, it should have been obvious that it would flee anything in its path,, it is General McClellan's chicken."

Joe smiled. "Okay, perfect. I just wish we could be sure that joke we came up with wandering us would not earn us a blue card for being too risque, that one where I say at least I'm not as upset as my wife when she is in her minstrel cycle."

"I think it's been long enough that just calling him chicken is enough without having to discuss whether he was trying to lose, " Abraham replied.

"That's one reason I thought you would be best to mention the dish each time."

Abraham thought that it would be okay if Joe refer to it also. "However, I think the audience only to hear the name twice, once when I mention it as one of our newest dishes and once when I come back."

"Sure. You're sure you don't mind the last bit?"

"To be perfectly frank, I'm a little pleasantly surprised that you bother to be concerned," Abraham said.

"I know," Joe said. "But baseball teams are integrated in many places, and teammates seem to interact with them fairly well. I think this new Vaudeville has the same potential to bring people together."

"And, what our fathers went through during the Civil War definitely means we have become... friends, even. Not just business partners."

Joe agreed, after which he picked up a plate and threw a creampie in Abraham's face. Both began to laugh.

"And I know you'll find a way to give me a pie in the face too, later on. Once we have our little invention established," Joe said as Abraham wipe the pie off of his face.

"I'm sure I will," Abraham said with a smile as he finished wiping his face off. "There aren't a lot of areas yet where our races are consistently together. The dream our fathers had can live on, however. What they went through will not have to be in vain. Who knows how long it would have taken otherwise. It might be a long while yet till we are totally accepted as equals everywhere. But this can be a great beginning."

A few years later, the audience in that Cleveland Restaurant & Vaudeville Club laughed hard as Abraham gave Joe a pie in the face as a reward for some of the shenanigans Joe had done.

Backstage, James Garfield, now elderly in his 70s, shook both of their hands. "I have been following the two of you with great interest. I am glad I was able to move back here after my presidency."

There aren't a whole lot of other cities where this could be done. I'm glad we have a place like this, we have traveled to Pittsburgh and even played in Peoria," Abraham said.

""And, the greatest stage of all awaits you." The former President grinned. "My good friend is the father of your agent. And after all I have dealt with working to ensure that radical agenda of equality could come to pass as much as it could, I wanted to be the one to congratulate you. You got a booking in New York. Every night for two weeks."

The men gasped and shrieked with excitement as they looked at the contract former President Garfield showed them. Their dreams, and the dreams of so many, were coming true. They were only a small comedy duo in the grand scheme of things. But like many before, they were blazing a wonderful trail.

Last edited:

So, Garfield is never murdered as he was in RL?Backstage, James Garfield, now elderly in his 70s, shook both of their hands. "I have been following the two of you with great interest. I am glad I was able to move back here after my presidency."

Correct, Red has said that he would like three straight terms of Republican presidents of two terms each. While he was uncertain about Grant or Chamberlain (or Stanton, who could also die in office and someone takes his place), Garfield was a constant.So, Garfield is never murdered as he was in RL?

Chapter 45: So with You My Grace Shall Deal

The days of the rebellion appeared numbered as the third year of the war started. The decisive victories of the summer of 1863 couldn’t be followed up with the expected final coup against the Confederacy, but Southern resources, manpower and morale had been pushed to the breaking point. The Confederate Congress had been forced to extend all enlistment terms beyond their initial three years and expanded the draft to men as young as seventeen and as old as fifty, a decision that made General Grant exclaim that they were robbing “the grave and the cradle”. Grant was far from the only Union leader who saw these weaknesses, for Lincoln and other Generals like Reynolds and Thomas could identify them too. But their hopes for a decisive victory in the first months of 1864 blinded them to the Union’s own weaknesses and allowed the Confederacy, in its last great hurrah, to launch a counterattack that pushed many Yankees into despair and pessimism once again, imperiling Lincoln’s reelection, emancipation and civil rights, and maybe the Union itself.

In hindsight, the fate of the Rebellion was clearly sealed in the previous summer with the dismal strategic and material losses suffered in those fateful campaigns. But at the time, the Confederacy seemed still full of defiance and fight. As almost always, the eyes of both combatants were placed on the Virginia front, where they believed the decisive battle would be fought. That the ugly carnage at the Mine Run had failed to break the Army of Northern Virginia had somewhat reinvigorated the faith of the Southern soldiers on General Lee. It had also demoralized the Northerners, who had believed their foes all but defeated but now prepared for new and bloody struggles. The knowledge that Lee would not be broken so easily influenced the decision of many a veteran not to reenlist as their three-year terms came to an end in the first months of 1864. This was the first of the “flaws in the Union sword and hidden strengths in the Confederate shield” that evened the odds.

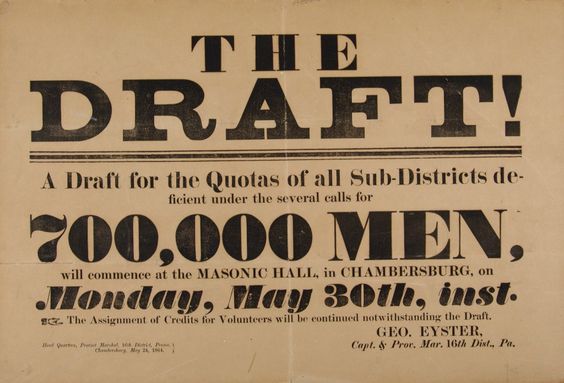

Indeed, some of the most experienced veterans in the Army of the Susquehanna, men who had seen combat from Baltimore to Mine Run, were now slated to return home soon. The Union government had decided against following the example of the Confederacy of requiring them to stay by law. Instead, they hoped to encourage the soldiers to reenlist voluntarily, offering them a special 400-dollar bounty and a thirty-day furlough. Aside from this material reward, the government appealed to their patriotic pride by allowing reenlisting soldiers to call themselves “veteran volunteers” and declaring that regiments where at least three quarters of the soldiers reenlisted would retain their identity and unity, which created “effective peer pressure” on those reluctant to remain in the Army. A Massachusetts veteran complained of how the Union used its soldiers "just the same as they do a turkey at a shooting match, fire at it all day and if they don't kill it raffle it off in the evening; so with us, if they can't kill you in three years they want you for three more”. But, despite his war weariness, this soldier decided to reenlist.

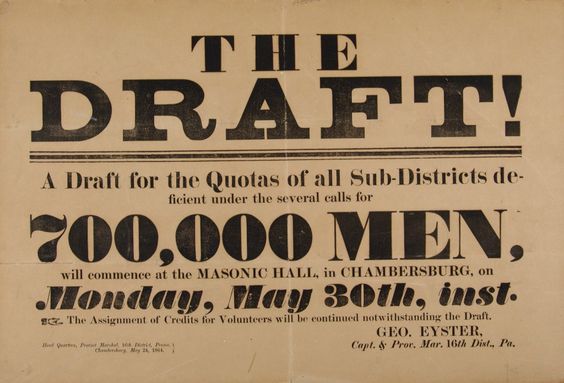

Men drafted into the Army usually had lower morale and weaker commitment to the cause

Some 136,000 veterans followed his example and reenlisted for another three-year term; a hundred thousand decided they had had enough. The Army of the Susquehanna was the most affected of all Union Armies, for only 60% of its effectives decided to reenlist. When this low reenlistment rate was coupled with its high casualty rate, the highest among all Union armies, it meant a serious reduction in its combat capacity, for the experienced veterans would have to be replaced by green conscripts. The veterans that had reenlisted often regarded these conscripts with contempt, one Pennsylvania officer even thanking “a kind providence” for the fact that his new recruits kept deserting. Those "gamblers, thieves, pickpockets and blacklegs would have disgraced the regiment beyond all recovery had they remained”, he declared.

Altogether, the replacement of experienced veterans with green conscripts resulted in a plunge in moral, strategic readiness, and tactical capacity. All Union armies experienced these negative effects even before the veterans had left for home, because those who had decided not to reenlist usually felt an enormous aversion to taking risks during their last weeks, limiting their usefulness and damaging the morale of their comrades. The whole process, although “judicious and wise” was “like disbanding an army in the very midst of battle”, concluded General Sherman, who recognized how it weakened the Union Army at a critical juncture. By contrast, the rebel armies seemed to be quickly recovering their fighting esprit despite privations and defeats. As the Richmond Dispatch gloated, Yankee victories weren’t “producing the slightest disposition to succumb, or in the remotest degree shaking the firm and confident faith” of the rebels.

This was not completely true. Sherman and others might have thought that “the masses” were “determined to fight it out”, when in truth a great part of the “masses” was tired of war and quickly becoming ready to accept anything to get the peace they longed for. But at the start of 1864, the great majority of White Southerners were still probably in favor of the war and willing to make sacrifices to win it. This ardor was most pronounced in the Confederate Armed Forces, compared with the civilian population. This is because “the men who were the most dedicated to the Confederacy had most readily put on uniforms and taken up arms to repel the Yankee abolitionists”. Consequently, most of the men in the Confederate Army, especially those in the Army of Northern Virginia, would have probably reenlisted voluntarily even if the law hadn’t compelled them first.

Most rebels shared Lee’s conviction that “if victorious, we have everything to hope for in the future. If defeated, nothing will be left for us to live for”. The apprehensions of a Virginia soldier, of having “our property confiscated, our slaves emancipated, our leaders hung” and Southerners reduced to “serfs in the land of our fathers” appeared now frighteningly real due to the course the Union was charting. These fears, that had inspired secession, “only grew in power as the war lengthened, more loved ones suffered and died, and the hated enemy’s commitment to abolition, confiscation and employment of black troops increased.” With these “atrocities from which death itself is a welcome escape”, as Jefferson Davis called them, so close, the soldiers were decided to “fight the insolent invader until Dooms Day or until we have been destroyed”.

These deeply held fears and the dedication to prevent their realization would not have been enough to motivate any army if they weren’t joined with real hope and confidence in victory. Some of this hope was based on the enduring idea that Dixie soldiers were superior to their Yankee counterparts, and that never mind temporary setbacks “the Confederacy will at once gather up its military strength and strike such blows as will astonish the world”, as John Jones declared. But in 1864 most Southerners pinned their hopes in defeating Lincoln’s reelection. “If southern armies could hold out until the election”, McPherson explains, “war weariness in the North might cause the voters to elect a Peace candidate who would negotiate Confederate independence”.

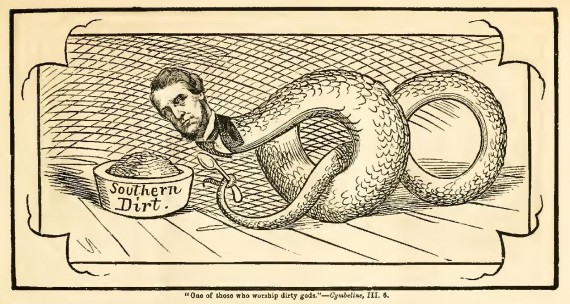

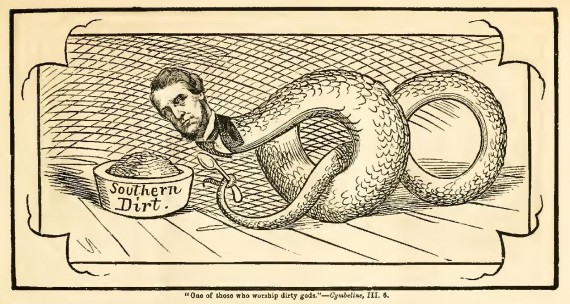

Copperheadism proved remarkably resilient, refusing to die and reviving in times of Union misfortune

The only way to bring about this electoral defeat for Lincoln was in accomplishing military victories on the field. Confederate politicians and soldiers well understood that if they managed to resist the Union invaders and to make the war too costly for them in blood and treasure, they may opt for peace come the next November. A Georgia newspaper was entirely right when it observed that whether Lincoln "shall ever be elected or not depends upon . . . the battlefields of 1864”; from the same state, a soldier said that “If the tyrant at Washington be defeated his infamous policy will be defeated with him.” Consequently, Lee, his soldiers, and his lieutenants, intended to “resist manfully” the next Yankee offensive. "If we can break up the enemy's arrangements early, and throw him back,” said Longstreet, “he will not be able to recover his position or his morale until the Presidential election is over, and then we shall have a new President to treat with”.

Naturally, the Union’s leaders were unwavering in their resolve to crush these hopes by crushing the Confederates first. The months between the Battle of Mine Run and the New Year had been filled with anxiety and dismay. Oversanguine Northerners had pinned unrealistic hopes on Reynolds, and when instead they were met with that slaughter, where the Union suffered 50% more casualties, they couldn’t help but turn despondent. Proof of low Northern spirits were that wistful war songs like “When this Cruel War is Over” seemed more popular than joyful carols that Christmas. “Oh, how many homes are ‘weeping sad and lonely’ because Reynolds couldn’t march to Richmond!”, bemoaned newspapers that just last spring were hailing him. The General, who not only never learned how to play politics but actively refused to on principle, was not capable of dealing effectively with such waspish criticism.

Even worse, some of that criticism was coming from Lincoln himself, who, instead of keeping his promise of not meddling, constantly inquired about Reynolds’ plans, and reminded him of the people’s clamor for a battle. Reynolds could not help but feel that the President was being unfair, criticizing him from a position of military ignorance and, instead of shielding him from political meddling, being the main exponent of it. Though Lincoln’s relationship with Reynolds never soured to the point it had with McClellan, differences in temperament and expectations between the two men did prevent the Union war machine from working as well as it might have otherwise. At the very least, it meant that the Breckinridge-Lee team was more united and mutually supportive than Lincoln and Reynolds were.

One thing in which the President and his General were in full agreement was that Lee’s Army and not Richmond was the “objective point”. Consequently, the plans drafted were meant to reach Lee and force him into battle. After Mine Run, the Army of Northern Virginia had taken a position along the Rapidan, which although an excellent defensive line had stretched the rebels thinly due to their dwindling numbers. Forced to man a 25-mile-long line, the graybacks would find it difficult if not impossible to prevent the Federals from crossing the river. “The animal must be very slim somewhere,” Lincoln observed. “Could you not break him?” But Lee understood how precarious his position was too and started to plan an offensive-defensive counterstroke that would force Reynolds to face him on his terms. “A constant readiness to seize any opportunity to strike a blow,” Lee proclaimed to Breckinridge, “will . . . thwart the enemy in concentrating his different armies and compel him to conform his movements to our own.”

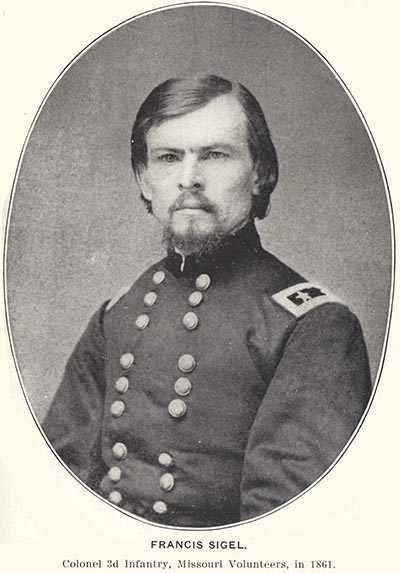

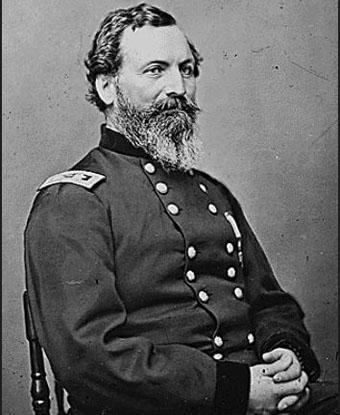

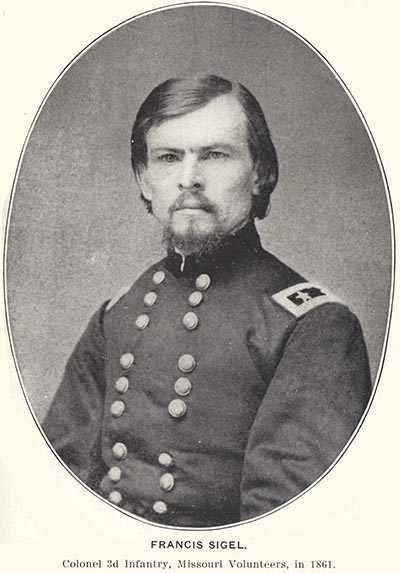

The opportunity seemed to present itself in “that vale of Union sorrows”, the Shenandoah Valley. A Confederate offensive against the demoralized and understrength Army of the Valley could relieve the pressure on Lee and interfere with Reynolds’ plans. That was what had happened, after all, in previous Valley Campaigns. In the interest of repeating history Lee even assigned Jackson to the Valley, where he would face enemies he had already beaten. Indeed, and despite his previous failures, General Siegel was in command of the Union forces there. Breckinridge agreed to the plan, moving the Richmond garrison and some North Carolina coastal units into the Army of Northern Virginia, to make up for the lost of Jackson’s corps, which advanced into the Valley in January.

Franz Siegel was a political general appointed and retained mostly to maintain the loyalty of German Republicans

The new Valley campaign was so like the first two that it was almost comedic. As before, the feared Stonewall was able to outmaneuver and dazzle his Union opponents, with the help of his hardy foot cavalry and the support of the guerrillas that swarmed the area. The demoralized garrison at Front Royal, dishonorably enough, surrendered quickly after it was encircled by one such combination. In another farcical repetition of history, Jackson easily defeated Siegel at Winchester in March, capturing the large supplies there – one of the soldiers even joked that Siegel should, like Banks, also be nicknamed “Commissary”. Altogether, the whole campaign had been such a dishonorable fiasco on the Union side that a reporter even refused to write about it, instead telling his readers they should just read the dispatches of the last campaign. It was the “same story of dishonor, of idiocy, of cowardice, so painful we cannot bear to repeat it”.

This new Valley defeat had caused not only embarrassment in the North, but also panic. Mounting fears over a “Second Invasion” caused such alarm that there were riots in Maryland and lynchings in Pennsylvania. In truth, Jackson had pushed the health of his corps to the breaking point, with the forced marches during the winter resulting in serious outbreaks of disease that precluded any further campaigning. Jackson’s quiet retreat to Virginia in April was perhaps not triumphant, but he had accomplished all his strategic objectives. Reacting to the initial invasion in January, Reynolds ordered a corps under General Slocum to Harpers’ Ferry, while militia meant to reinforce the Army of the Susquehanna was instead posted at the Potomac, all these reinforcements not rejoining the main command until months afterwards. More importantly, the Valley offensive pushed Reynolds to rush his attack.

Taking advantage of a seeming break in the harsh winter weather, Reynolds tried to flank the Rapidan line from the West, advancing through Madison County. But this hasty movement resulted in an even more embarrassing fiasco, the inglorious “Mud March”. Showing that apparently even the Almighty was against the Union, a few days after the march started “the heavens opened, rain fell in torrents, and the Virginia roads turned into swamps”. Artillery and wagons sank hopelessly into the mud, with triple teams of horses unable to even budge them. Some men were even threatened with drowning as the mud rose to their shoulders and to the ears of their mules. The only part of the Army to avoid this fate was William French’s corps – which, in its haste to flee the mud moved too far away from the main body and was easily routed by Lee’s troops. Though the attack on French’s command was not followed up because the rebels were afraid of sinking into the mud too, it completed the Yankees’ humiliation.

At Philadelphia, Lincoln was completely dismayed. The President of course knew that Reynolds could not control the weather, but he still was impatient for a triumph, deeply aware that such disasters as the Valley and the Mud March were already sending the Northerners into despair. A grim Reynolds promised that he would force Lee into that fight as soon as the roads dried up. It took almost two months, until March, for the weather to improve. By then Reynolds was ready, his campaign getting off to an auspicious start. With both a new Peninsula Campaign and an attack through the Wilderness out of question, the new offensive would focus on taking Fredericksburg, a strong position protected by the Rappahannock.

The Confederate lines were undermanned, and when the Federal cavalry under Bayard advanced to take Fredericksburg’s crossings, its rebel counterpart under Stuart found it hard to concentrate quick enough. A furious clash followed, but even though Stuart managed to repudiate most of Bayard’s troopers, Reynolds and the Union infantry had managed to cross the river and seize the high ground. When Lee’s infantry under Jubal Early belatedly arrived, they were unable to dislodge their foes, leaving Lee with no other option but to retreat towards Spotsylvania Court House.

The Battle of Spotsylvania Court House

Reynolds immediately gave chase. Jackson’s corps was still busy in the Valley, and though that meant that some of his units were still there too, Reynolds still enjoyed numerical superiority. This was the chance of fighting Lee he was waiting for, and he was not going to throw it away. Unfortunately, the hurry to fight Lee kept Reynolds from seeing the strength of the trenches the rebel commander had built along the Ni River. This was not the first time trench warfare was employed in the Civil War, but the battle demonstrated their usefulness by making Reynolds initial bold charge come to bloody grief. But Reynolds was undaunted, sending his troops in a flanking maneuver the following day. Lee’s trenches at Laurel Hill again held up, and despite the heavy casualties suffered, the Battle at Spotsylvania could only be considered a Confederate victory.

A dogged Reynolds was not willing to disengage just yet. It was clear that the next defensive position would be the North Anna River, twenty-five miles to the south. Reynolds hoped he would be able to strike Lee before he reached the river, sending in Hancock’s corps. Covered by the dimming light and Bayard’s troopers, Hancock managed to get to the side of Lee’s advancing column, suddenly jumping between Ewell and Early, capturing hundreds of prisoners. But what little light remained disappeared quickly, creating confusion and disorganization in the ranks of both armies as soldiers could hardly see who they were shooting at. “I believe that most of our men fell by the fire of their own comrades”, a Union soldier said after the battle, himself the victim of one of the numerous tragic friendly fire incidents suffered that night. Nonetheless, Hancock had managed to inflict some 3,800 casualties on the rebels at the cost of merely 1,300 casualties, a clear victory.

However, Lee obtained a consolation prize: the capture of one of Reynolds couriers. The information the youth carried made Lee realize that Reynolds was farther to the south than previously thought, which in turn resulted in Lee deciding against a counterattack, instead rushing to the North Anna position. Reynolds, for his part, did not move just yet. Believing that Hancock had lost, he backtracked. This not only prevent him from following up Hancock’s victory but resulted in Lee winning the race to the North Anna. There, the rebels quickly dug a line of trenches to protect the Hanover Junction, which extended from the Chesterfield Bridge to the pivotal Virginia Central Railroad. The strong bluffs at the center Ox Ford would force Reynolds to attack the flanks, either the dirt fort at the bridge or the crossing at Jericho Mills.

Union probes at both the Ox Ford and Jericho Mills were unsuccessful, but a corps under Meade managed to overwhelm Ewell’s hastily dug trenches and the poorly designed fort. Ewell suffered basically a mental breakdown, screaming hysterically for the men to rally. It was ultimately Longstreet, and not Ewell’s cries, that managed to prevent the disintegration of the Confederate flank, but Meade had still gained a bridgehead. Not to be outdone, General Sedgwick, supported by Doubleday, advanced into Jericho Mills. The more capable Jubal Early managed to strike his flank, inflicting heavy casualties, but Sedgwick had nonetheless managed to establish a bridgehead too.

By then the mounting casualties of 30% had reduced the Army of Northern Virginia to merely 31,000 men, but there was no possibility of abandoning Hanover Junction. At night, Lee organized his army into an inverted V, its apex situated at the Ox Ford. This brilliant coup, courtesy of Lee’s principal engineer, would create an almost impregnatable defensive position, demonstrating for future generations the power of trenches. For their part, the Yankees had also suffered great losses, and were now feeling the strain of several weeks of campaigning. “Their uniforms were now torn, ragged, and stained with mud; the men had grown thin and haggard”, commented a soldier. “The experience of these days seems to have added twenty years to their age.” Mindful of this, Reynolds allowed his troops some rest. The second day then was only filled with skirmishing, albeit of unusual intensity.

The Battle of North Anna

But at 4:00 am on the third day, the Union corps got into position, and advanced at the sound of three salvos shot into the air. The still morning gave way to a great battle cry, as the Army of the Susquehanna, exhausted and bloodied as it was, advanced with determination and enthusiasm. “A cheer, that has been heard on nearly every battle-field in Virginia, went up from 60,000 brave hearts, white and black, and told the story to friend and foe that the Army of the Susquehanna was on a charge and pushing for the main works of the enemy,” reported a Vermont captain. According to a colonel, the Union war cry, a “full, deep, mighty cheer" that expressed "defiance, force, fury, determination, and unbounded confidence . . . swept away all lingering fears and doubts from every manly breast like mists before the whirlwind.” But this glorious moment quickly lost its luster, as Meade’s troops got bogged down in chilly swamps, green conscripts skedaddled from the battlefield, and charges stalled with the commanders unable to force the hesitant troops forward.

One of the ugliest episodes of the war ensued when Doubleday’s USCT troops managed to take a rebel breastwork. Either brave or insane, the soldiers leapt over the trenches and managed to capture sections of it. But the battle quickly deteriorated into savage hand to hand combat, “an unmitigated slaughter, a Golgotha without a vestige of the ordinary pomp and circumstances of glorious war”. The Black soldiers, as in previous engagements, showed they could fight and die as bravely as their White comrades and foes. But this did not earn the rebels’ respect, but only their hatred. Claiming that they had declared “no quarter”, and because “their presence excited in the troops indignant malice”, the rebels “disregarded the rules of warfare which restrained them in battle with their own race and brained and butchered the blacks until the slaughter was sickening.” The singular savagery of the fight is best illustrated by the fact that this testimony came from a Confederate.

Confederate resistance may not have been as savage in other sectors, but it was just as violent and ferocious. Murderous fire cut down whole blue regiments, making green conscript and veterans in their last weeks run for the rear. By dawn, a sickened John Sedgwick allowed his soldiers to fall back. At the same time as this lessened the pressure, a stray shell fell on the tent of General Hancock. The resulting explosion knocked Hancock unconscious. With its commander hors combat, the II Corps found itself leaderless, confused, and desperate. The opportunity was clear, and it was quickly seized by Longstreet. In a charge spearheaded by the Texas brigade under the aggressive John Bell Hood, Meade was forced back. The retreat was at first orderly. Then, the panicked men of Hancock’s corps ran by, making their comrades despair and decide to quickly flee too. A rout had started.

At that moment Reynolds appeared on the field. Holding up the American flag, the commander decided to lead the reserve to stop the rout. His inspirational, brave actions motivated the reserve into a mighty charge that pushed Longstreet back. And then a sharpshooter shot Reynolds' horse from below him. Panic quickly spread through the Union ranks. The USCT regiment, which despite the slaughter was still holding into the rebel position desperately, was finally forced back, those who remained behind being quickly and sadistically executed. Meade, too, retreated from his position, believing it necessary to prevent another rout. Finally, the senior commander, Sedgwick, took charge and ordered a general retreat towards Fredericksburg.

Bitter recriminations followed the Federals as they retreated. Doubleday insisted that he could have carried the rebel flank had Meade remained in his position and had he received reinforcements. Furious at the slaughter faced by his men, he all but accused Meade of being a murderer and a racist. Or at least that was what the thin-skinned Meade heard. A shouting match ensued, again completing the humiliation felt by the Army of the Susquehanna as it limped northward. The Army had lost 14,500 casualties to the rebels’ 7,500, much of the disparity owed to the massacre of Black troops left behind during the retreat. In total, the entire campaign had costed 32,000 casualties, or 37.7% of the Army of the Susquehanna. The Confederates lost 22,500 men, a proportionally higher 48% of their Army. But grieving Northerners were not consoled by percentages as they read the seemingly endless casualty lists.

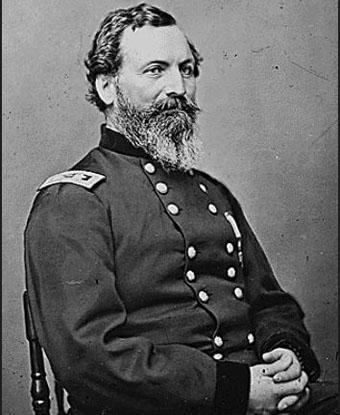

John Sedgwick

That the campaign had accomplished nothing but the slaughter of thousands in terrifying scenes was keenly felt. “These nearly two weeks have contained all of fatigue & horror that war can furnish”, commented Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. This despair was shared by the President. As in previous campaigns, Lincoln haunted the telegraph offices, and when news came of the grievous losses and the subsequent retreat, he sank into a chair and exclaimed “Why do we suffer reverses after reverses! Oh, it is terrible, terrible, this weakness, this indifference of our Susquehanna generals, with such armies of good and brave men!” By contrast, Richmond was “ablaze with joy upon learning that Lee had once again driven away the invader”, the happy citizens leading a throng to serenade Breckinridge.

At the same time as the Virginia campaign came to grief, the Georgia front was approaching a similarly unhappy conclusion. As in the East, this debacle was a result of a host of unfortunate circumstances, from the replacement of veterans with conscript to a maladroit shuffling in the military command. The seeds of the ensuing disasters were planted last year when the aborted offensive towards Dalton left the Lincoln administration greatly disappointed in General Thomas. Dark whispers circulated in Philadelphia, saying that he had turned out to be another McClellan, and even accusing him of being a secret traitor. That Thomas had failed to build up his reputation and connections in the capital was clear in the fury of both Stanton and Lyons at his lack of action.

“The patience of the government is exhausted”, Lyons wired. “It is said that, like McClellan after Washington, you have been unable to follow up your previous victories. The pressure for your removal is growing”. Lincoln privately vented similar frustrations, and, on Stanton’s recommendation, turned to General John M. Schofield to dynamize the department. Born in New York, Schofield grew up in Illinois, before securing an appointment to West Point. Dismissed from the academy due to a disciplinary matter, Schofield managed to get the Board of Inquiry to reconsider with the help of Senator Stephen A. Douglas. The board accepted Schofield’s appeal, with the lone vote against coming from then Lieutenant George H. Thomas.

This incident may have not only informed Schofield’s latent conservatism, but also his constant criticism of Thomas. Originally assigned to Missouri, Schofield worked as the right hand man to Lyons, who was impressed by his “conspicuous gallantry” and his efforts in favor of Missouri Unionists. After Lyons went East, Schofield remained in charge of defending Missouri, which he did competently but conservatively, managing to maintain some order amidst the bloody bush war. In the summer of 1863, Schofield managed to turn back an ill-conceived attack led by Sterling Price with minimal Union casualties. Seeing in this general the fighter that Thomas was not, Stanton and Lyons both urged Lincoln to place him in a more prominent place. Following the battle of Dalton, Schofield was assigned command of the Department of the Ohio, encompassing Kentucky and, critically, all of Tennessee.

This shuffle meant that many regiments that had been under Thomas’ command were now transferred to Schofield, including most of the rear-guard troops that had been protecting his supply lines from guerrillas. The War Department justified the change by arguing that those guerrillas operated in both Kentucky and Tennessee, and thus it was more logical for Schofield to focus on them while Thomas could focus on Georgia. Brushing aside Thomas’ protests, the War Department ordered him to make a move soon, to coincide with Reynolds’ expected offensive. Thomas again protested, pointing to the unpredictable weather, and asking to postpone the offensive until March. But an irate Lyons snapped back that he had had “enough time standing around doing nothing”, and that he had to move lest Johnston be able to send reinforcements to Lee.

John M. Schofield

Though Thomas obeyed orders and prepared to advance, apprehensions remained within the War Department that the advance would stall yet again. Schofield’s continuous and unsubtle lobbying then finally bore fruit, as Philadelphia granted him permission to assemble an Army and march it to Chattanooga to support Thomas’ offensive. This Army was to be independent of Thomas’ command in all but the broadest strategic points. To add insult to injury, Thomas first found about this when he read a dispatch from the New York Times that lavished pride on Schofield for having “inspired the whole West with enthusiastic faith in his courage, uniting energy with military skill”. His protests again came to naught, for Thomas simply didn’t have the necessary clout and had lost too much goodwill by his delays, whether they were justified or not.

Shortly after the New Years, Schofield arrived at Thomas’ headquarters. What Thomas didn’t know, but probably suspected, was that Schofield had been given secret orders to assume command of the Army of the Cumberland should Thomas falter. That explained the frosty reception Schofield received by Thomas and his subordinates. An awkward meeting ensued, as Thomas proposed to follow the Snake Creek Gap plan he had been unable to put into operation last fall, which entailed a feint towards Dalton followed by an advance towards Resaca. Jealous of his newfound independence, Schofield refused to consider playing second fiddle to Thomas, insisting instead on swinging through Northern Alabama into Rome, Georgia. Seizing this critical railroad terminus would then force Johnston to retreat towards Atlanta, lest he was cut off.

Thomas and Schofield struggled to choose a plan, and at the end decided instead to execute both at the same time. Schofield made the first move, advancing towards Rome. Johnston was alerted of the move by his cavalry. Though at first he had hoped that Cleburne could come to his aid, a military buildup near Mobile made the Irishman unwilling to abandon his command. A panicked Johnston then immediately decided to evacuate Dalton, surprising Burnside who had just arrived to demonstrate against Dalton as ordered by Thomas. The affable federal had been sent to Georgia leading a corps of green conscript, a move Lyon permitted to both placate Thomas and bolster his chances. Mistakenly believing that Johnston was fleeing from him, Burnside hurled his corps at Johnston. But the piecemeal attacks carried out by inexperienced draftees unsurprisingly failed, causing a 4 to 1 disparity in casualties.

By the time Thomas arrived, he found only a few scores of stragglers. This was disappointing to the Yankees, but in Richmond Breckinridge was aghast at how Johnston had retreated without even trying to fight first. In response to a prodding telegraph by Secretary Davis, Johnston assured his government that “I have earnestly sought for an opportunity to strike the enemy” and would soon do so. And yet, when Thomas approached again Johnston just retreated once more, yielding up 25 miles south of Resaca without a fight. Some Confederates seemed to consider this a masterful sacrifice of territory in exchange of time, which was also drawing the Federals deeper into a hostile country where Johnston could easily destroy them. “Time is victory to us and death to our enemies”, the Richmond Sentinel stated confidently. But Breckinridge and Davis were afraid that there was nothing behind Johnston’s actions except reluctance to fight, and that he would never make a stand as promised.

These fears where shared by Georgia Governor Brown. Arguing that Atlanta was “almost as important” to the Confederacy “as the heart is to the human body”, Brown demanded to concentrate all available troops and either send them as reinforcements to Johnston, or into Tennessee, where they could cut Thomas’ overextended supply lines and either delay or stop him. A bristling Davis replied that Brown could not “decide on the value of the service to be rendered by troops in distant positions”. But at least someone else thought that Brown’s plan was both practicable and threatening – Schofield. The Yankee general had arrived in Rome, but a rebel deserter and rumors gathered by Union spies said that Cleburne was going to thrust into Nashville.

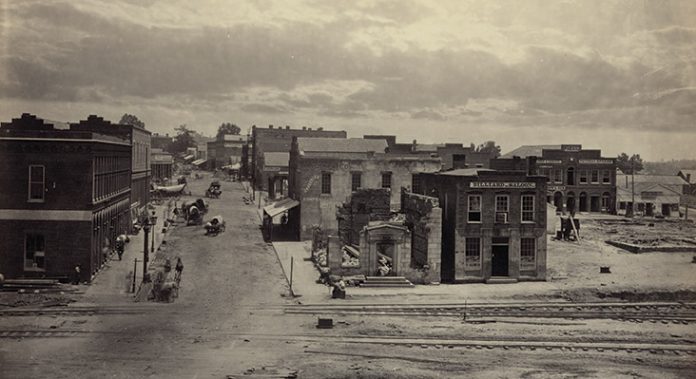

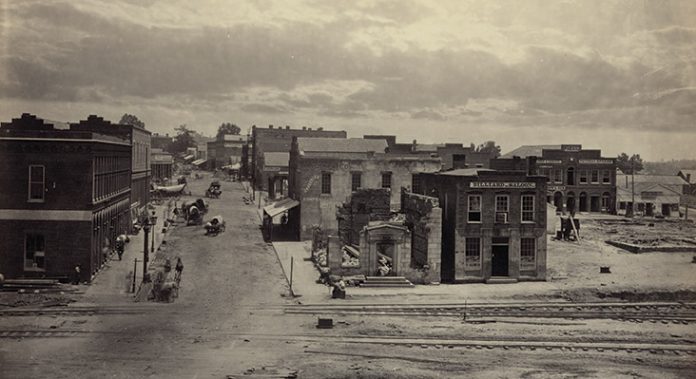

Atlanta during the Civil War

After failing to verify whether the information was true or not, Schofield prudently decided to link up with Thomas. Reports that Forrest’s cavalrymen were gathering in Northern Alabama, and the evident importance of maintaining their supply lines, made the commanders decide to send reserves to Tennessee and post additional troops along their supply lines. The number of men protecting the Yankee rail communications by then was nearly equal to the number of front-line soldiers, yet another factor diminishing the Union’s advantages. Happily for the bluejackets, the concentration of Union forces in his front made Johnston decide to retreat once again, falling back across the Etowah River.

For Breckinridge, this was the final straw. In less than two weeks Johnston, without fighting a single battle, had given up 45 miles of ground and allowed the enemy to get halfway to Atlanta. Telling Davis sadly that “Johnston has failed and there are strong indications that he will abandon Atlanta”, the President decided to bolster the Army of Tennessee and inject necessary fighting spirit into it sending two hard-fighting generals there as reinforcements. The first was Cleburne, who, taking advantage of how Grant too had to let go of whole corps, slipped to Atlanta. The second one was Longstreet. Reynolds had just been pushed back at the North Anna, and since Jackson had returned from the Valley Breckinridge thought it safe to transfer him West. Before Longstreet left, Breckinridge took him to the side and emphasized that the Confederacy desperately needed a counterattack to save Atlanta and thus itself. Breckinridge was in fact giving Longstreet carte blanche to act even if Johnston demurred.

Lincoln and Breckinridge had now both shuffled their decks, and when the cards were down it turned out that the rebel leader had drawn the better hand. Indeed, and despite Johnston’s resentful uncooperativeness, the genial Longstreet had been able to ingratiate himself to the other commanders and start to draft plans for a counterattack. Meanwhile, Thomas and Schofield could still not cooperate, both putting in operation separate plans against Johnston’s line at the Allatoona Mountains. Neither was able to flank the rebels, and both suffered a terrible disparity in casualties during their initial probes. Seeing an opportunity, Johnston authorized General Polk to strike Thomas’ right flank. But the attack was poorly executed and was furthermore delayed by the gallant defense conducted by Philipp Sheridan. Before long another Union column arrived and Polk was the one who was hit in the flank, forcing his bloodied corps to retreat.

Previous to this setback, Johnston had issued a proclamation where he promised that Polk’s flanking attack was the beginning of the awaited counterattack. “We will now meet the foe’s advancing columns and hurl them from our soil”, Johnston promised. “Soldiers, I lead you to battle.” According to a private, “the soldiers were jubilant” at hearing the order: “We were going to whip and rout the Yankees”. But after Polk failed, Johnston immediately lost his nerve and retreated yet again, this time to Marietta. The soldiers could scarcely believe this; even Johnston’s own chief of staff wrote that “I could not restrain my tears when I found we would not fight”. For their part, the other commanders were furious. That’s when the Army of Tennessee linked up with Longstreet’s reinforcements, Johnston finding just then of Breckinridge’s orders. Discord ensued, as Johnston found Breckinridge’s actions to be a double-faced insult, a “cold ungentlemanly attack on my honor as an officer”.

Disagreements were also brewing in the Yankee ranks. The feared offensive into Tennessee by Forrest’s troopers had at last materialized, forcing Thomas and Schofield to send even more reinforcement west. By then the Army of the Ohio was little more than a corps, too small to act independently. Begrudgingly, Schofield accepted to cooperate more closely with Thomas, but angling for overall command, he still sent telegraphs to Philadelphia complaining of “generals who mistook strategy for doing nothing”. Perhaps conscious that his command was on the line, Thomas decided to gamble it all in a risky operation. Ordering General Negley’s corps to demonstrate against Johnston’s front, Thomas planned to swing the bulk of his army to the rebel’s right flank.

Battle of Manrietta

The plan was risky because it left the forces in the front isolated and without reserves. But if successful, the Union soldiers could cross the Chattahoochee River, which would result in the Federals being closer to Atlanta than the Confederates, leaving Johnston no choice but to fight. Afraid of this possibility, Johnston, predictably and disappointingly, prepared to simply withdraw again. This was more than enough for the other commanders. In an act that Johnston and those sympathetic to him would forever denounce as rank insubordination and usurpation, Cheatham, Cleburne, and Longstreet refused to move, and prepared to make a stand right there and then.

In the evening light, three Union corps under Generals McCook, Burnside and Schofield advanced towards the Confederate right. Alerted by rebel scouts in the Big Kennesaw, the Southern units moved to intercept them. The first fight started between Schofield and Cheatham, whose resistance managed to stall the blue advance. At the same time, McCook clashed with Cleburne atop Black Jack Mountain, the experienced troops on both sides fighting ferociously. Burnside’s corps, made of green troops, launched an attack at Soap Creek that was stopped by Longstreet’s veterans. As night fell, the result was stalemate, neither Army being able to push the other back. But Thomas’ wide movement had left him right next to his objective of the Chattahoochee River. Even if he didn’t accomplish a tactical victory, a strategic triumph was still a possibility.

And then the Yankee plans started to unravel. Afraid that the Confederate forces could surge forward and cut off the railroads, Schofield started to shift to the west and closer to Negley. He asked McCook to shift west too, and, even though Schofield was not in command of him, McCook obliged, merely informing Thomas through a courier that got lost in the night and would only arrive the next day. These ill-conceived movements created a gap in the Federal line between McCook and Burnside, but before Thomas could solve the issue the rebels advanced. At first unaware of the gap, Longstreet and Cleburne were delighted to find this opportunity. Just as Thomas was conferring with McCook, a powerful attack hit the corps on the side, sending the Yankees flying. Among the casualties was McCook, who was wounded and captured when a rebel regiment suddenly burst into his campground. Thomas, for his part, had managed to ride away, but in the confusion, few knew that he had escaped and rumors that he had been captured, or even murdered, swept the Union forces.

With Thomas apparently lost, Schofield took command, as his orders from Philadelphia permitted. The rout had resulted in heavy casualties and the army was panicked and weary, which made Schofield decide to retreat. But the remnants of McCook’s corps were leaderless and still under attack. Decided to prevent a complete rout, Philipp Sheridan started to rally the men with much energy and even more profanity. That’s when Thomas “like a vision you dare not hope is true”, appeared, none for the worst except for a wound where a bullet had grazed his leg. Immediately Sheridan rode out, shouting “Thomas lives! Stop running God damn you, Thomas lives!” The men, who had fallen into despair when they thought their leader was dead, now found themselves imbued with new fighting spirit. Hats went into the air and cheers resounded before Sheridan quieted them down. “God damn you, don’t cheer!”, he shouted. "If you love your country, come up to the front! . . . There's lots of fight in you men yet! Come up, God damn you! Come up!"

Quickly retaking charge, Thomas ordered his commanders to stand “like a rock” and counterattack, the charge being spearheaded by Negley. But unfortunately, the conflicting orders confused the Army, as some soldiers and officers still believed that Thomas had died and thus continued to retreat as Schofield had ordered. The result was that Schofield was leaving the battlefield, Burnside was practically paralyzed, and an unsupported Negley only managed to get a bloody nose. This in turn allowed Cheatham to hammer Schofield, while Cleburne and Longstreet launched a desperate attack against both Sheridan and Burnside. Despite the fact that their hasty trenches were not completed, they withstood the Confederate advance. But Schofield’s withdrawal had isolated Thomas, who, nonetheless, refused to run until the night despite continuous waves of Southern attacks. “Phil”, the Virginian said when Sheridan pointed that they had no more reserves, “I know of no better place to die than right here".

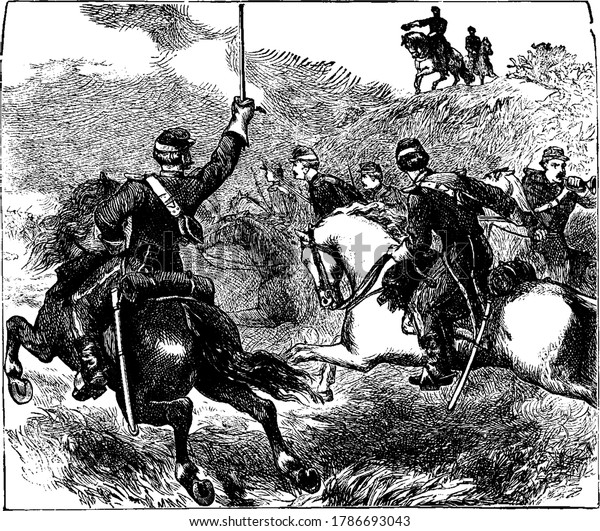

Sheridan rallying the troops

But no matter Thomas’ decisiveness, the situation was turning hopeless. At that moment a column of dust was spotted. Tense minutes passed while a soldier tried to discern whether the enemy’s reinforcements were coming to strike their rear. “It’s the Colored flag!”, the soldier exclaimed in relief. Indeed, the USCT corps under General Palmer was approaching to relieve Thomas’ besieged force. John M. Palmer, a founder of the Illinois Republican Party and a Radical, was a competent officer but prickly about rank. Loyal to Thomas, Palmer detested Schofield, not only because he was junior in rank to him, but also because he found all the political scheming Schofield had conducted to be dishonorable. When Schofield assumed command temporally, Palmer had refused to obey him and instead was going to counterattack when news that Thomas was alive but in great peril reached him. Through a forced march, Palmer and his USCT troops arrived in the nick of time and saved Thomas from a final Confederate wave.

Still, and despite this last-minute save, the Army of the Cumberland had been badly bloodied and was completely confused and demoralized. If Johnston decided to launch an all-out attack, it might break down. The disparity in casualties, of 16,000 Federals to 11,000 rebels, was disheartening, and the odds of the Yankees driving the rebels away after taking such punishment were nil. Recognizing this, at nighttime, Thomas ordered a general retreat to Acworth, but a pursue by a dogged Cheatham forced the Army to continue its retreat to Allatoona. There Schofield even proposed to abandon the pass, but Thomas refused. However, this last suggestion completed the break between Schofield and Thomas. The commanders, loyal to Thomas, all were rather furious with Schofield as well – Palmer believed him a coward and a schemer, Negley blamed him for the senseless attack against Johnston’s front, and Sheridan thought he had been too willing to believe the rumors that Thomas was dead in his haste for assuming command.

The two main Union offensives during the first months of 1864 thus ended in bloody failure. A host of factors explain this result, from discord within the command structure, to the need to divert thousands of troops to fight guerrillas, and principally the replacement of thousands of veterans with green conscripts. By contrast, the Confederates enjoyed the advantages of fighting on their own territory, with shorter interior lines and powerful defensive positions manned by experienced and motivated veterans. Consequently, the Union had been unable to make any significant advances towards either Richmond or Atlanta and had paid dearly in treasure and blood. Of course, its material superiority meant that it could replace its losses quite easily, while conversely the Confederacy could not afford the also grievous losses it sustained. But in its spite of their cost, these blows accomplished a collapse in Northern morale and a resurge in Southern spirits that might just carry the Confederacy to independence.

“Who [is] so blind,” a Virginian thundered as Reynolds was driven back, “as not to be able to see the hand of a merciful and protective God” in accomplishing this “wonderful deliverance of our army and people from the most powerful conflagrations ever planned for our destruction!” A Georgia newspaper was just as exuberant when it declared that Thomas “has been successfully halted in his mad career and Gen. Johnston has said to him, ‘Thus far shall thou come, and no further.’” Unless the situation changed, Lincoln would probably be defeated next November, if he was even renominated, that is. Republicans were “discouraged, weary, and faint-hearted”, while buoyed by these failures the Copperheads seemed to revive and regroup behind a platform that called for “an honorable peace”. “Who shall revive the withered hopes that bloomed at the opening of this year’s campaigns?”, asked the New York World for example.

John M. Palmer

It was to try and revive those hopes, and to plan a strategy that might carry the Union to victory in the summer, that Lincoln decided to pay a visit to General Reynolds’ headquarters. The General was to meet with him and General in-chief Lyons. After dealing with Reynolds, the President also hoped to meet with Thomas and straighten-out what he sardonically called one of his “family controversies”. Jumping around in crutches due to the broken leg he suffered when his horse was shot from under him, an undaunted Reynolds arrived at the small Fredericksburg house where Lincoln and his party were staying. In a fateful decision, the General ordered his military guard to patrol around the block. This was done in the interest of privacy, but it meant that this reunion of the Union’s leaders was to be guarded just by one soldier, who went off to get drunk, and the brawny Ward Hill Lamon, who accompanied Lincoln as his bodyguard. None of the men present seemed to consider that a problem at all. And three men outside considered it a blessing, for it allowed them to enter the house to try and decapitate the Union. A few minutes later, shots were fired and by the time soldiers rushed into the building four men laid dead.

In hindsight, the fate of the Rebellion was clearly sealed in the previous summer with the dismal strategic and material losses suffered in those fateful campaigns. But at the time, the Confederacy seemed still full of defiance and fight. As almost always, the eyes of both combatants were placed on the Virginia front, where they believed the decisive battle would be fought. That the ugly carnage at the Mine Run had failed to break the Army of Northern Virginia had somewhat reinvigorated the faith of the Southern soldiers on General Lee. It had also demoralized the Northerners, who had believed their foes all but defeated but now prepared for new and bloody struggles. The knowledge that Lee would not be broken so easily influenced the decision of many a veteran not to reenlist as their three-year terms came to an end in the first months of 1864. This was the first of the “flaws in the Union sword and hidden strengths in the Confederate shield” that evened the odds.

Indeed, some of the most experienced veterans in the Army of the Susquehanna, men who had seen combat from Baltimore to Mine Run, were now slated to return home soon. The Union government had decided against following the example of the Confederacy of requiring them to stay by law. Instead, they hoped to encourage the soldiers to reenlist voluntarily, offering them a special 400-dollar bounty and a thirty-day furlough. Aside from this material reward, the government appealed to their patriotic pride by allowing reenlisting soldiers to call themselves “veteran volunteers” and declaring that regiments where at least three quarters of the soldiers reenlisted would retain their identity and unity, which created “effective peer pressure” on those reluctant to remain in the Army. A Massachusetts veteran complained of how the Union used its soldiers "just the same as they do a turkey at a shooting match, fire at it all day and if they don't kill it raffle it off in the evening; so with us, if they can't kill you in three years they want you for three more”. But, despite his war weariness, this soldier decided to reenlist.

Men drafted into the Army usually had lower morale and weaker commitment to the cause