You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Una diferente ‘Plus Ultra’ - the Avís-Trastámara Kings of All Spain and the Indies (Updated 11/7)

- Thread starter Torbald

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 48 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

38. Ventos Divinos 39. The Great Turkish War - Part I: El Reino de África 40. The Great Turkish War - Part II: The One-Eyed Sultan 41. The Great Turkish War - Part III: Blood in the White Sea 42. The Great Turkish War - Part IV: Rûm 43. The Great Turkish War - Part V: Otranto 44. The Middle Sea Transformed 45. Ilhas de OfirI would especially like to see an update on France, especially since the Habsburgs aren’t ruling Spain it would definitely effect the expansionist projects of France. I’d imagine the French would more much more successful in chipping off parts of Germany and Italy for itself.

Pretty unlikely to happen as the Habsburg‘s position in Germany would be reinforced and they still have both Burgundy and Imperial lordship over Ilan, while Naples is in the hands of SpainI would especially like to see an update on France, especially since the Habsburgs aren’t ruling Spain it would definitely effect the expansionist projects of France. I’d imagine the French would more much more successful in chipping off parts of Germany and Italy for itself.

But the HRE recently went through a few nasty civil conflicts wouldn’t that weaken the HRE enough for France to take a bit of an advantage and seize bits of land? Also I assume Spain won’t be as active in fighting France as much right?Pretty unlikely to happen as the Habsburg‘s position in Germany would be reinforced and they still have both Burgundy and Imperial lordship over Ilan, while Naples is in the hands of Spain

I don't think Spain would be blind to the consequences of France managing to expand their eastern borders given they also have designs on their southern borders. Plus there is also the fact that the natural ally of France against the HRE is the Ottomans another thing Spain would very much object to.But the HRE recently went through a few nasty civil conflicts wouldn’t that weaken the HRE enough for France to take a bit of an advantage and seize bits of land? Also I assume Spain won’t be as active in fighting France as much right?

If anything I reckon without the Habsburgs having to spend so much time governing such disparate people and territory it is more likely the HRE and Spain are more successful against France ITTL.

Exactly my point.I don't think Spain would be blind to the consequences of France managing to expand their eastern borders given they also have designs on their southern borders. Plus there is also the fact that the natural ally of France against the HRE is the Ottomans another thing Spain would very much object to.

If anything I reckon without the Habsburgs having to spend so much time governing such disparate people and territory it is more likely the HRE and Spain are more successful against France ITTL.

HRE is NOT a single entity and Burgundy + no Spain reinforce a lot the Habsburg position there, so is more likely seeing France losing border lands (aka the ones who once belonged to Charles the Bold) than the Habsburgs.But the HRE recently went through a few nasty civil conflicts wouldn’t that weaken the HRE enough for France to take a bit of an advantage and seize bits of land? Also I assume Spain won’t be as active in fighting France as much right?

I don't think Spain would be blind to the consequences of France managing to expand their eastern borders given they also have designs on their southern borders. Plus there is also the fact that the natural ally of France against the HRE is the Ottomans another thing Spain would very much object to.

If anything I reckon without the Habsburgs having to spend so much time governing such disparate people and territory it is more likely the HRE and Spain are more successful against France ITTL.

Fair point actually. I assumed since without the Habsburgs ruling Spain Spain wouldn’t get dragged into constant conflict in Europe. I still believe that they won’t be that devoted into fighting France but I will say that they will fight France occasionally if it gets bad enough.Exactly my point.

HRE is NOT a single entity and Burgundy + no Spain reinforce a lot the Habsburg position there, so is more likely seeing France losing border lands (aka the ones who once belonged to Charles the Bold) than the Habsburgs.

Fair point actually. I assumed since without the Habsburgs ruling Spain Spain wouldn’t get dragged into constant conflict in Europe. I still believe that they won’t be that devoted into fighting France but I will say that they will fight France occasionally if it gets bad enough.

France became the enemy to beat for Spain as soon as they had the Reconquista business over. They are neighbors, they had conflicting interests in Italy, and they had claims in each other's border areas (Navarre and the Rousillon). They became dragged into European (read: HRE) conflict due to the Hapsburg inheritance, but it's worth remembering that the Hapsburg inheritance came to be in the first place because Spain created a set of marriage alliances around France to contain and fight them.

That’s a fair point. But in OTL France and Spain did sign a treaty where Italy would be deicidas between them so it wasn’t as if there wasn’t a possibility of reconciliation.France became the enemy to beat for Spain as soon as they had the Reconquista business over. They are neighbors, they had conflicting interests in Italy, and they had claims in each other's border areas (Navarre and the Rousillon). They became dragged into European (read: HRE) conflict due to the Hapsburg inheritance, but it's worth remembering that the Hapsburg inheritance came to be in the first place because Spain created a set of marriage alliances around France to contain and fight them.

Well, that happened but is likely who both Kings had the intention to screw the other since the beginning as happened... Also Ferdinand remarried to Germaine but peace with France was short livedThat’s a fair point. But in OTL France and Spain did sign a treaty where Italy would be deicidas between them so it wasn’t as if there wasn’t a possibility of reconciliation.

I think what could be possible is that France and Spain could try to a sign a treaty where they would agree to relinquish certain territories to the other in exchange for peace though even peace is a tough one.Well, that happened but is likely who both Kings had the intention to screw the other since the beginning as happened... Also Ferdinand remarried to Germaine but peace with France was short lived

Possible, but both Kings would know who peace would not last much longI think what could be possible is that France and Spain could try to a sign a treaty where they would agree to relinquish certain territories to the other in exchange for peace though even peace is a tough one.

Oh definitely.Possible, but both Kings would know who peace would not last much long

Yeah the reason I had these thoughts was because I was crafting an idea for a similar TL myself.

That’s a fair point. But in OTL France and Spain did sign a treaty where Italy would be deicidas between them so it wasn’t as if there wasn’t a possibility of reconciliation.

OTL France and Spain signed hundreds of treaties. They meant roughly none of them, they still fought dozens of wars.

Yeah fair point.OTL France and Spain signed hundreds of treaties. They meant roughly none of them, they still fought dozens of wars.

42. The Great Turkish War - Part IV: Rûm

~ The Great Turkish War ~

Part IV:

- Rûm -

The Ottomans disembark at Otranto, 1570

Part IV:

- Rûm -

The Ottomans disembark at Otranto, 1570

One quiet morning in 1570, when the April sun cleared the morning fog outside of the city of Otranto, for the first time in 89 years, an Ottoman army had landed on Italian soil.

From a low-hanging cliff, Piyale, Sultan Mehmet III’s trusted Kapudan Pasha, his grand admiral, Piyale, oversaw the disembarkation of 16,000 men and 71 bronze cannons directly to the south of Otranto. On the northern side of the city, another 9,000 men and 28 cannons unloaded on the beach. Brought with him was an ideological weapon: his lieutenant, a full blood Italian turned corsair renegade, known to the West as “Occhiali.” Born Giovanni Dionigi Galeni, Occhiali was taken captive at the age of 17 from a village in Calabria in 1536 and used as an oar slave. After converting to Islam in 1541 and receiving the the Turkish name Uluç Ali (from which his Italianized nomenclature came), Occhiali became a corsair himself and served under Dragut before earning his own fleet which operated out of Tripoli. With a near 30-year career in the Mediterranean, Occhiali was already a household name in Italy, and Piyale was hopeful that putting him front and center in the campaign would serve to convince the Italian populace of the benefits that came with peaceful submission to the High Porte and conversion to Islam.

A full-blown Italian invasion had been long in the works. Apart from being the spiritual center of the perfidious infidel, Rome was also of great symbolic importance to the Ottoman sultans, who had for generations laid claim to the direct inheritance of the Roman Empire. For the janissaries, the sultan’s crack troops, the name of the Eternal City was one of their common warcries - indeed, when the janissaries, sipahis, akinjis, azabs, and yayas poured into Avlonya and Durazzo in 1569, the Adriatic ports reverberated with chants of “Rûm! Rûm! Rûm!” There was even a familial impetus to taking Italy: The mother of Mehmet III’s eldest son, Mustafa, was the daughter of a Venetian officer, captured in the 1520s, while Mustafa himself was betrothed to an Italian woman himself, a captive from Monopoli in Apulia, given the Turkish name Meleksima. Now that Italy was both logistically and financially within arm’s reach of the Ottoman war machine, each passing day carried with it equal certainty of an imminent Turkish invasion.

The entire peninsula had perhaps never been more vulnerable to a Turkish invasion. Imperial authority had mostly withdrawn from Northern Italy to contend with more pressing threats from France and the League of Fulda, allowing the princes of the region to return to their quarrelsome past. Similarly, the kingdom of Spain - wrapped up in a revolt in Iberia and a largescale Islamic counter offensive in North Africa - had essentially left the defense of Southern Italy in the hands of the local population and the viceroys of Naples and Sicily. All the while, every inch of the Italian coast from Pescara to Sorrento had been aggressively harassed by Barbary Corsairs and Turkish privateers, tenderizing the southern seaboard for the establishment of potential beachheads. Apart from the difficulties facing Southern Italy’s Spanish defenders to the west, the decades following the conclusion of the the most recent Habsburg- Valois war in Northern Italy had led to intensifying chaos throughout the entire peninsula.

Piyale, Kapudan Pasha

- Sangue e contesa -

Since the 4 year popular uprising (1494-1498) of the Dominican friar and populist leader Girolamo Savonarola, a fever had been building in Florence - and the rest of Northern and Central Italy, by extension. The sorry and negligent state of the Renaissance Church was certainly no less acutely felt in Italy than elsewhere, and the mounting demands for an end to clerical corruption were accentuated by a desire to also see an end of the rampaging interventions of foreign armies and unscrupulous condottieri. The ejection of the French from Lombardy in the 1530s (and then from Savoy in the 1540s) and the shifting of Habsburg and Spanish attention elsewhere had also allowed the smaller powers of Northern Italy to align themselves into new coalitions and revisit old wounds and ambitions. The already fragile situation in Northern Italy was further shaken in 1551 when Massimiliano Sforza was blocked by a makeshift barricade near Balocco on the way back from Turin, and, after his guards dismounted to inspect it, the duke of Milan was fatally shot in the collarbone by an arquebus ball as he leaned out the door of his carriage to take a look. The assassin was never caught, and, while Massimiliano had accrued a great number of upper class rivals and lower class dissidents, the motives for the murder remained entirely ambiguous.

As Massimiliano’s eldest son had died in 1547, his second born, Ludovico, established Massimiliano’s 12-year old grandson, Giancarlo, as duke of Milan, with himself acting as regent. Ludovico was vigorously interested in continuing his late father's policy of political domination in Northern Italy, and almost immediately undertook aggressive actions against the Republic of Venice. Conscious of the republic's increasingly hated status in Europe due to its perceived subservience to the expanding Ottoman state, Ludovico Sforza did not bother to hide his designs on the rich cities of the Venetian Terraferma.

With the cooperation of his brother-in-law, Adriano, the duke of Savoy, and Ercole II d'Este, the duke of Ferrara, Ludovico campaigned against Venice (and Mantua as well for a short period), capturing Bergamo before being captured in defeat near Brescia. After being ransomed, Ludovico pursued war against Venice once again, capturing Brescia. With Charles V von Habsburg threatening to intervene in 1555 (having defeated the League of Fulda at Darmstadt in 1554), Massimiliano II - having reached his majority - was forced to recall his uncle and sue for peace with the Venetians, handing back Brescia but retaining Bergamo. However, the Venetian Republic never fully ratified the surrender of Bergamo, and the numerous dust-ups started by the regency of Ludovico di Sforza would continue to entangle Northern Italy well into the next decade.

Meanwhile to the south, the Florentine Renaissance and the long reign of the Medici family had been brought to an abrupt end by Savonarola’s uprising in 1494, creating an opportunity which was seized by the notorious condottiero (and illegitimate son of Pope Alexander VI) Cesare Borgia, who entered Florence with a Papal army and declared the city to be under his indefinite protection as Papal Gonfalonier. Hoping to take advantage of the situation and further Imperial interests in Central Italy, Maximilian von Habsburg had extended an alliance to Cesare and invested him with a new title, that of the “Grand Duke of Tuscany.” Cesare used this title (now paired with his pre-existing title of “Duke of Romagna”) as pretext for an invasion of the Republic of Siena, which was also a nominal French ally. Siena fell to Cesare in 1518, although an exiled republican government in Montalcino continued its resistance for another 4 years. A considerable swathe of Central Italy - straddling the Italian peninsula from the Adriatic to the Tyrrhenian Sea - was now gathered under the Borgia family, meaning that Fabrizio, whose only son had died childless before him, would be succeeded by the closest Borgia scion.

The Florentine masses were by no means satisfied with the Borgia ascendancy. Savonarola’s prophecy foretelling a rejuvenation of Christendom and the purification of the Church through fire seemed to be thoroughly vindicated by the sack of Rome in 1512 by French gendarmes and Swiss mercenaries and the natural death of the widely detested Pope Julius II the very next year. This was confusingly reversed when Florence - proclaimed by Savonarola as the new Jerusalem - was surrendered without a fight 2 years later to the vengeful bastard son of one of history’s most debauched Popes. Most of Central Italy - particularly the urban centers - shared in this long-standing discontent, and were therefore willing to entertain increasingly radical and theological ideas. Ideas that spread even into Spanish-held Naples with the assistance of the well-connected Vittoria Colonna, the widow of the marquis of Pescara, Fernando d'Ávalos and the second wife of Cesare Borgia. In spite of the the closeness of the Holy See, Protestant thought had found its way into Northern and Central Italy, and a number of Protestant theologians had sprung up from the native academia and clergy, such as Girolamo Zanchi in Lombardy, Gian Paolo Alciati in Savoy, Pier Paolo Vergerio in the Republic of Venice, Bernardino Ochino in Siena, and Pietro Martire Vermigli in Florence - the latter two being in direct correspondence with Vittoria Colonna for a time. Each of these men would eventually be executed or forced into exile, but their conversions had swayed more followers and were indicative of the growing social and spiritual anxiety in the region. To add to the instability, the discontinued Italian Wars between the French, the Spanish, the Habsburgs, and their local allies threatened to break out once again over the succession of Fabrizio Borgia, Duke of Romagna and Grand Duke of Tuscany, and the son of Cesare Borgia and his second wife, Vittoria Colonna, as Fabrizio’s closest surviving male relative was across the Mediterranean, the 4th Duke of Gandía, Francisco de Borja - a Spaniard.

Francisco de Borja leaving Spain to press his claim in Italy

The placement of Francisco de Borja on the ducal throne of Tuscany and Romagna was deeply concerning to the Valois and the Habsburgs. If Juan Pelayo were to see to it that Francisco’s claim came to fruition, the larger share of the Italian peninsula would fall under either direct or indirect Spanish control, with the Papal States wedged in between. This was a position from which the king of Spain could intrude on the Holy Roman Emperor’s traditional sphere of influence, and strong-arm the Pope into doing his bidding. The Habsburgs were not so keen on the Avís-Trastámaras continuously sticking their noses where they did not belong, and the Valois were even less keen on seeing the Spanish using the papacy to uphold their outrageous territorial claims to the Americas, Africa, and Asia. Some detente between allies was achieved at a 1552 meeting in Modena between Diego Hurtado de Mendoza and Eustace Chapuys, the respective ambassadors of Juan Pelayo and Charles V, in which the Spanish delegate assured Chapuys that his sovereign had no intention to incorporate Tuscany and Romagna into his realm, although the Imperial delegate countered with the Emperor’s offer to purchase the duchies in question outright, for the sizeable sum of 400,000 ducats. However, the ongoing war in Germany convinced Charles V to concede the matter for the time being, and Juan Pelayo never reneged on his support for Francisco de Borja’s claim. The preceding arrival of the Duke of Alba and his tercios in Genoa in 1547 was therefore both a calculated deterrent against French re-entry into Italy, and an enticement of military assistance to Charles von Habsburg in crushing the Swabian revolt in exchange for a concession of hegemony over Central Italy. With the 20 Years’ War continuing to unfold to the north and the west, the matter remained unresolved and Florence and Siena adopted provisional administrative councils under small-scale Papal military supervision, while a Papal governor took control of the duchy of Romagna.

- Sieben Siegel und sieben Trompeten -

The chaotic byproduct of the tumultuous interconfessional warfare to the north of the Alps soon began to pour over into Italy as well. The dynamic and thriving Swiss Cantons had effectively been sidelined by the continuously up-and-coming House of Habsburg in the Swabian War of 1499 and the Fällkrieg of 1514-1520, with the Swiss Confederation neutered by Emperor Maximilian at the turn of the century and essentially dismantled in 1520. The old confederations’ constituent cantons were further divided by the religious fault lines that came with the emergence of Protestantism, with the Protestant and Catholic cantons stiffening their adherence to their respective sects and entering into frequent, bloody feuds.

Beginning in the 1540s, the Protestant cantons of Bern, Aargau, Solothurn, and Neuchâtel had to contend with an energetic Catholic Swiss military leader by the name of Ludwig Pfyffer. Although he was only officially elected magistrate of Luzern in 1566, Pfyffer had been the city’s de facto leader for decades, and used his influence and connections to turn Luzern into a center of Reform Catholicism and its associated intelligentsia, and eventually form a “Golden League” of the seven Catholic cantons. Despite often receiving implicit support from the Habsburgs, Pfyffer was a proud Swiss patriot and strove to re-assert Swiss autonomy at every opportunity, and opted to align himself with the duchies of Milan and Savoy, which were both similarly distancing themselves from the Habsburgs. Outcry over this often violent interreligious contest made its way back to Vienna, where in 1557 the Kaiser issued emissaries to the predominantly Protestant free cities of Bern, Freiburg, and Solothurn to demand that they either rein in or forcibly disband their native free companies. The immediate effect of this disruptive situation was the increased percolation of Protestant mercenaries out of Switzerland and into Northern Italy.

The growing religious and political tension of the Swiss-Italian sphere came to a head in the form of one particular Bernese mercenary company in the employ of Massimiliano II of Milan. Having just lost their commander to an infected arquebus hole in his leg, a council of leading officers took charge of the free company, of which a certain Matthias Gruber soon became the de facto leader. Young, charismatic, and uncompromising in his beliefs, Gruber was also a spiritual guide to his fellow Swiss mercenaries, who mostly belonged to the same congregation of Brethren of the Word (Andreas Karlstadt's more radical sect of Protestantism) that had come to dominate Bern and Freiburg. This particular congregation was known colloquially as the "Alpine Brethren," or Alpenbrüder, for their homeland and also for their protection of Protestant refugees fleeing Italy via the Alpine passes and their role in the dissemination of Protestant literature back into Italy via those same passes. They were also noticeably more intense in their adherence to the teachings of Karlstadt than most of their coreligionists elsewhere, owed in part to their precarious proximity to the anti-Protestant Habsburgs, Sforzas, and di Savoias.

The moral rigor of these Alpenbrüder companies made them honest dealers and passionate fighters - both desirable traits to potential employers - but also infused them with an apocalyptic fever that was welling up dangerously beneath the surface. When pestilence broke out at Mantua, the Alpenbrüder alone were spared by their isolation from their more debauched compatriots and their refusal to buy baubles from the local markets or cavort with the local prostitutes and camp followers. This exemption by the Angel of Death seemed as clear as day to Matthias Gruber to be a sign from God that the Alpenbrüder had His blessing and it was time to take matters into their own hands and return to Milan.

Having already been filled with agitation by 3 months without movement and a year and a half without pay, and with disgust by what they saw as the corruption and licentiousness of the local Italian authorities and the Roman Church, the Alpenbrüder zealously followed Gruber back to Milan to demand their rightful wages from Duke Massimiliano II. In abject debt from nearly two decades of intermittent warfare, Massimiliano was in no position to surrender liquid payment, and entreated the Alpenbrüder to await approval of a loan from the Genoese. They emphatically refused to wait, and forced an entrance into the city. Overreliance on Swiss mercenaries had left Massimiliano with very little homegrown soldiers to fall back on, and - what was more - the cheapness of Swiss mercenaries from Protestant cantons compared to those from Catholic ones (the latter also being constantly in the service of the Habsburgs) had also led Massimiliano to purchase the services and fill his duchy with thousands of armed men who were more than likely to sympathize or even join the Alpenbrüder. Massimiliano escaped Milan by one gate as Matthias and his Alpenbrüder entered through another, the young duke fleeing on horseback to the court of his uncle, the duke of Savoy.

The unexpected ease of taking Milan fanned the fervor of the Alpenbrüder, and Matthias Gruber set about tightening his grasp on Milan to pave the way for the establishment of a borderline theocratic form of Karlstadter administration. The unrest of the Milanese locals and the potentates in the surrounding countryside - coupled with news of Duke Adriano of Savoy securing the pledged assistance of Ferdinand von Habsburg, duke of Tyrol and Further Austria, in exciting the Alpenbrüder from Milan - convinced Gruber and his followers to abandon the city and move southward to the more defensible landscape of the Apennine piedmont. However, their numbers were growing every day, with the greater share of the assorted Swiss mercenary companies across the upper Po Valley abandoning their commanding officers and joining the ranks of the Alpenbrüder (alongside a not-so-insignificant number of Italian sympathizers).

In a heightened apocalyptic frenzy, the Alpenbrüder had become convinced that it was upon them to inflict God's judgement in Northern Italy just as the Israelites were ordered to destroy the Amalekites, with the ultimate goal being the city of Rome itself and the toppling of Papal power. In the early months of 1563, the crushing defeat of an army led by Alfonso II d'Este (who barely escaped with his life) at Torrile and the brutal massacre of most of its surviving components strengthened both the resolve of the Alpenbrüder and their emergent reputation of infernal invincibility, and more importantly laid Parma and Modena open to pillage.

The moral seriousness and egalitarianism of the Alpenbrüder coupled with their success in upsetting the local powers-that-be initially gave them a strong appeal to the commoners, who had grown utterly distraught at the return of inter-ducal struggles and full-blown condottieri warfare in Northern and Central Italy. However, the Alpenbrüder were, at the end of the day, mercenaries, and were therefore accustomed to ghastly outbursts of violence, destruction, and thievery in the aftermath of victory, which was now also tinged with vengeful religious fanaticism. Soon conflicting views on the treatment of captured priests and monks along with the desecration of churches, icons, and the remains of saints would quickly sour the cautious support extended by the Italian middle and lower classes, and the Alpenbrüder would be unable to garner enough local support to fully occupy any city they took.

Last stand of the Alpenbrüder

After almost two years of chaos, the inevitable Milanese-Savoyard-Habsburg army arrived in early 1564, and broke the Alpenbrüder at Ponte Ronca and killed Matthias Gruber himself. Yet even this defeat did not end the affair, and the Alpenbrüder regrouped and resumed their insatiable warpath south of the Apennines in the contested duchy of Tuscany. While unable to take Florence, the Alpenbrüder still wreaked havoc across Romagna, Tuscany, and even Lazio, reaching as far as Viterbo - which they despoiled - raising fears that Rome would be sacked a second time. The Alpenbrüder may have fizzled out more quickly after their defeat at Ponte Ronca if not for an opportune anti-Papal uprising in nearby Siena. Disgruntled by the dissolution of their republic and their subjugation to Florence - and then to de facto Papal rule - the citizens of Siena frequently rose in rebellion, although never with much success. However, when another seemingly unimposing rebellion occurred in May of 1564 and seemed near collapse, the closeness of the rampaging Alpenbrüder (returning northward from Viterbo) presented an enticing solution to a small ring of crypto-Protestant burghers who had personally known the Protestant theologian Bernardino Ochino and referred to themselves as the “Eletti” (the “Elect”). After communicating discreetly with the leading officers of the Alpenbrüder and opening the Porta dei Pìspini under the cover of night, the mercenaries entered the city and made short work of the minimal garrison of the city’s Papal gonfalioner. The Eletti soon used the Alpenbrüder to sweep aside the city’s rebel leaders too, however, and resolved to re-establish the Republic of Siena but with an implicitly Protestant framework.

No matter the radical ideas flowing through Tuscany at this time - and through Siena in particular - the sudden insertion of more than five thousand armed Swiss Protestants and the nebulous, secretive intentions of the city’s new ruling oligarchy proved to be too much for the general public. The final straw came when a contingent of Swiss Protestants attempted to destroy the sacred head of St. Catherine of Siena. As night fell, an incensed mob stormed the makeshift barracks of the Alpenbrüder and - while repulsed - forced the Swiss to relocate outside of the city walls. The situation had become unbearable to the Papacy, but luckily a gradual change in policy since the death of Pope Paul IV in 1560 convinced the authorities in the Papal States to seek foreign intervention. The new pope, Pius IV, born Giovanni Angelo, was the first pope drawn from the Medici family, which had been expelled from Florence in 1494 and had largely resided in the kingdom of Naples ever since. While he had been selected with the approval of the dominant anti-Spanish faction in the Roman Curia, Pius IV’s familial obligations superseded those of his benefactors in Rome, and the unraveling of matters in Tuscany allowed him to both appease his Spanish neighbors and possibly obtain leverage to reinsert his kin into positions of power in their ancestral homeland. Communicating through the viceroy of Naples, Pedro Afán de Ribera, Pius IV offered to grant passage and military assistance to Francisco to Borja in securing the Grand Duchy of Tuscany and Romagna so long as he pacified the region. With 1,200 Spanish troops landing with him at Piombino in late 1564, Borja was joined by a 3,000 strong Papal army and a prepaid ensemble of German and Italian mercenaries, and marched towards Siena to restore order. Clashing with 3,200 Alpenbrüder along the way at Isola d’Arbia in March of 1565, the remaining Alpenbrüder dispersed in disillusionment.

However, just as Juan Pelayo seemed ascendant in the peninsula, the difficult passage of his Leyes Nuevas in Spain and waves of Berber counter offensives across North Africa drew the Spanish monarch’s attention elsewhere, and the house of Habsburg renewed the protection of their interests in Italy. With the Turks rebuffed in Hungary and a 10-year treaty signed in 1561, Philipp II von Habsburg was free to descend the Brenner Pass at the head of 8,000 Italian mercenaries, Tyrolean levies, and Hungarian horsemen. Invited to Rome by Pope Pius IV after driving back a massive Turkish army at Buda, Philipp II used this Papal commendation to enter Italy in a show of force, intended to intimidate the Venetians, to remind the Sforzas and di Savois of their loyalties as Imperial vassals, and, last but not least, to secure the allegiance of Francisco de Borja. Philipp II and the Spanish Borgia prince had an amicable meeting at Arezzo in 1566, guaranteeing Francisco’s deference to the Kaiser before the King of Spain, and ensuring that the title of Duke of Gandía would be abdicated to Francisco’s second son, Juan, while the Grand Duchy would pass to his eldest, Carlos (known to posterity as Carlo Borgia).

- La caduta del rivellino -

Uluç Ali - "Occhiali"

Uluç Ali - "Occhiali"

This discord in Italy was merely a garnish for the long-awaited circumstances of Mehmet III's designs on Italy. The winds had been shifting more and more favorably to a successful invasion of Italy for nearly two decades. In less than 10 years, fortuitous developments had been mounting across the White Sea: a solution to the Venetian problem in the form of their violent expulsion from Cyprus, Corfu, and other key islands in the Eastern Mediterranean; the installation of a pro-Turkish pretender on the throne of Tunis; the mobilization of the petty Kabyle Berber kingdoms against the Spanish-held ports between Tunis and Algiers; a resurgent Saadian principality seizing Agadir and Marrakech and threatening to overrun Portuguese Morocco; and an armed revolt led by some of Spain's leading nobles against their monarch. The plan of Mehmet III was a truly massive undertaking. Merely a week after the fleet of Mehmet III’s Kapudan Pasha, Piyale, embarked from Avlonya and headed to Otranto, a Barbary Corsair fleet under the command of Müezzinzade Ali Pasha, the bey of La Goletta, would depart from Tunis and land at Mazara del Vallo in Sicily, followed by another fleet under Damat Ibrahim Pasha, the beylerbey of Egypt, from Tripoli at Gela. Another week later - having waited out a storm in the Ionian Sea - a fleet from Durazzo arrived at Brindisi while fleets that had assembled at Corfu and the mouth of the Ambracian Gulf arrived in the Gulf of Taranto and the bay of Catania. Piyale Pasha dispatched Occhiali to Taranto, while Occhiali’s own lieutenant, another Italian renegade known to the West as Hassan Veneziano, assumed command at Brindisi. In a year’s time, at the height of the campaigning season in 1571, the Ottomans and their North African vassals and allies had fielded roughly 25,000 troops in Apulia, 18,000 in Calabria, and 42,000 in Sicily.

Every raw resource and industrial infrastructure available to the Ottoman State had been vigorously utilized for nearly 8 years to prepare a mass invasion. Galleys, galiots, and troop ships had been endlessly assembled at the arsenals of Konstantiniyye, Alexandria, Tunis, and Tripoli, their oars manned with slaves from Ruthenia, Greece, Hungary, Croatia, Spain, the Caucasus, and, most importantly, Sicily and Naples. Iron, timber, and pitch from the Balkans, textiles and grain from Egypt and Tunisia, navigators and experienced seamen from the Maghreb and the Aegean Isles, horses, mules, and camels from Anatolia, Hejaz, and the Levant - all poured in to the ports, foundries, and rallying fields to fuel and equip the Ottoman war machine. Countless manpower from every corner was called upon or volunteered themselves - elite janissaries, Tatar horse archers, Syrian ghazis, Slavic irregulars, Turkish conscripts, and more - and spent months or even years trekking across the mountains and valleys of the Near East and the Balkan Peninsula to muster at the ports of the empire. Upon setting sail, these fleets and their supply convoys numbered nearly 500 ships in total. Apart from their human cargo, they carried millions of yards of cloth, canvas, and parchment, hundreds of thousands of iron ingots, arrows, arquebus balls, millet bread biscuits, and barrels of pitch, tens of thousands of tents, beasts of burden, battleaxes, scimitars, spears, firearms, and hundreds of roaring cannons to pulverize the Turkish army’s way through the Italian Peninsula.

An Ottoman fleet at anchor in Durazzo

As the ravelin of Italy - and, by extension of Christian Europe - Otranto's fortifications received special attention and had been renovated multiple times since the city had been reclaimed from a surprise Ottoman invasion in the 1480s. The Ottoman beachhead may have been broken on the walls of Otranto if not for one auspicious event. The most commonly-held story is told accordingly: Two weeks into the siege, a Spanish Morisco conscript was moved by the sight of the crescents and Arabic calligraphy waving in the breeze, and the sound of the muezzins leading the call to morning prayer, and came to long for the faith of his ancestors. He abandoned his post and entered Piyale's camp at sunrise, where he informed the Kapudan Pasha that there was a spot in the southern curtain wall that was weak enough to be toppled by a single, well-aimed cannonball, and behind which was a massive gunpowder magazine. This particular stretch of wall had not been placed under any direct fire by the Turkish artillery or arquebusiers, as it was separated from the Ottoman line by a steep hill, and was therefore out of range of any established artillery placements. Nevertheless, Piyale immediately ordered the movement of six bronze cannons and and a massive Venetian-crafted bombard (ordered by Mehmet III as part of the 1565 treaty) known to the Italian as “La Cerbottana di Dio” - “God’s Peashooter” - into position to fire upon the magazine. The downwards slope of the hills left the artillery crews and their janissary guard completely exposed to the arquebusiers on the walls, but, despite the withering gunfire, La Cerbottana was able to land a large bitumen-wrapped shell, which punctured the wall and caused a massive explosion. Piyale redirected his entire janissary contingent and the bulk of his reserves to this opening - which was located at an undermanned section of the city - and soon the city was overrun. For the second time in less than a hundred years, an Ottoman army had stepped foot on the Italian peninsula and had taken the city of Otranto. This time their stay would be much longer, and much more devastating.

The quick siege of Otranto allowed Piyale to move on to Lecce before it had time to finish organizing its defenses, leading to a brutal sack. Brindisi quickly followed suit as morale among the Apulians dropped steeply. Hassan Veneziano moved to Bari, where a carriage carrying the remains of St. Nicholas of Myra barely made it out of the city before the Turks breached the walls, depositing the relics in Taranto, and thence to Naples. Other cities in the vicinity - such as Ostuni, Monopoli, Barletta, Andria, Altamura, and Matera - did not have anywhere near the same level of fortifications as Otranto or Brindisi, and were either beaten into submission or surrendered outright, each in less than two weeks. Only Taranto stood to offer up significant resistance, but was surrounded by Occhiali’s fleet at sea and Piyale’s army on land, and fell after 5 weeks. To the north, Foggia was abandoned ahead of the Ottomans, and was used as a staging point for the siege and capture of Lucera, to the west. The speed with which the Ottomans advanced in Southern Italy and along its shores can be attributed to the Italian element within the Ottoman sphere. Just as the Moriscos and Mudéjares were essential in the Turkish and Barbary subversion of the security of the Spanish mainland, the veritable legions of Italian slaves and renegades found in the Islamic ports and corsair fleets of the Mediterranean were extremely useful in allowing Piyale Pasha to pry the door open to the Italian Peninsula. Indeed, the Ottoman invasion would have been impossible if not for these renegades, many of whom knew the curves and byways of the Calabrian, Apulia, and Sicilian coastline better than the Christian galley captains assigned to protect them.

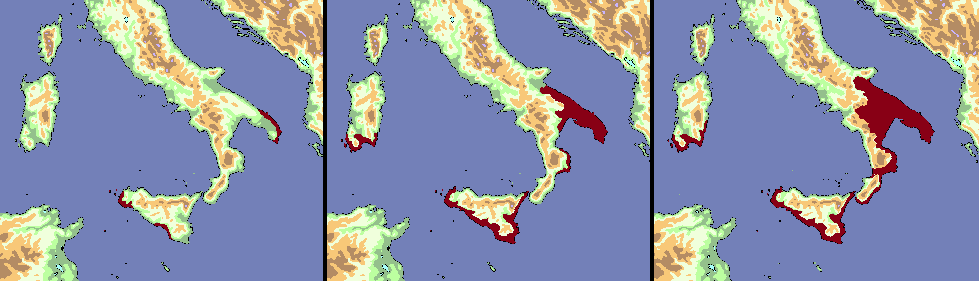

1) Red - Piyale Pasha

1a - Durazzo; 1b - Avlonya; 1c - Otranto; 1d - Brindisi; 1e - Bari; 1f - Barletta; 1g - Matera; 1h - Foggia and Lucera; 1i - Pescara

2) Green - Occhiali

2a - Corfu; 2b - Ambracian Gulf; 2c - Lepanto; 2d - Taranto; 2e - Crotone; 2f - Catanzaro; 2g - Reggio di Calabria; 2h - Messina; 2i - Catania; 2j - Syracuse

3) Blue - Müezzinzade Ali Pasha

3a - Tunis; 3b - Sousse; 3c - Monastir; 3d - Sfax; 3e - Mazara del Vallo; 3f - Sciacca; 3g - Marsala; 3h - Trapani

4) Purple - Damat Ibrahim Pasha

4a - Tripoli; 4b - Gela

5) Yellow - Murat Reis

5a - Bugia; 5b - Jijel; 5c - Annaba; 5d - Cagliari

With the powers of Europe rustling at this knife plunged into the heart of Christendom, Piyale Pasha and his subordinates knew that any gains in Italy would have to be made quickly and with as little fuss as possible, and so made a concerted effort to be tactful in occupying such large swathes of territory so densely populated by hostile Christians. Towns and villages that surrendered without a fight were treated graciously, and were usually billeted with Christian levies and mercenaries or often not garrisoned at all (depending on the strategic value of the settlement). Even among the towns that offered resistance, only one out of a handful would be specially brutalized - its buildings leveled, its inhabitants butchered, raped, or enslaved, and its spoils dispersed to the looting soldiers - so as to sufficiently terrorize the other towns into surrendering. As Mehmet intended to lord over these lands and their people, it was essential that they be treated leniency and that the seeds of Islam be planted among them. As conquering Southern Italy required dislodging its Spanish overlords, the same leniency was not offered in any shape or form to the local Spaniards. Any Spanish soldier unfortunate enough to be captured alive after his commander refused Ottoman demands for surrender was executed without exception. Their commanding officers often suffered a much more grisly fate, being burnt at the stake, skinned alive, or simply beaten to death. Those who surrendered when the terms were offered were spared execution, but were also usually subjected to some form of abuse. For instance, after the Spanish commander Garcia Diaz de Acuña surrendered Reggio to Müezzinzade Ali Pasha, the Turkish captain had the Spaniard's eldest daughter seized and shipped to Konstantiniyye to be added to Mehmet III's harem.

Spanish rule in Italy had been mostly stable, but was certainly not well-liked: the introduction of the Inquisition was widely unpopular, and the viceroyalties were seen as foreign apparatuses meant only to farm taxes to pay the Spanish army and to siphon staple foods to feed the overpopulated Iberian Peninsula. Popular uprisings were not uncommon, and the hills were rife with banditry. The local rift between the Spanish and Italians was therefore not difficult for the Turks to exploit. In one instance, when news arrived in Reggio that an Ottoman army had seized Catanzaro, the native Calabrians proceeded to ransack the homes of every wealthy Catalan and Castilian merchant family in the city - all before the Turks even appeared before the walls. These precautions to prevent unrest were not always successful, and sometimes were useless in dulling the spirit of resistance among the locals. For example, after the unexpected success in pushing the frontline northward after the capture of Foggia and Lucera, the Ottoman push - entrusted to Piyale Pasha’s Bosnian lieutenant, Hüsnü - ground to a halt due to stiff opposition coming from the rugged Gargano promontory. Drawing spiritual inspiration from the shrine to St. Michael the Archangel in Monte Sant'Angelo, the natives of Gargano regularly conducted debilitating guerrilla warfare against the Ottoman troops in the lowlands, and pledged to cast Hüsnü and Piyale into hell along with their "father," Satan. These measures were also not always followed by Ottoman and Barbary combatants. For example, Ivan Abdulov, a Muscovite traveler acompanying the Ottoman army in Calabria, records the janissaries regularly brutalizing the local inhabitants with little to no provocation. When the janissaries found a large number of the elderly sheltering themselves in a chapel in the Calabrian countryside, Ivan watched the janissaries march them out to the hills, strip them naked, beat them, and leave them lying in agony in the countryside. Ivan asked the janissary captain how they could act in such a cruel manner, to which the captain responded that "among us such deeds are a virtue."

Repairing the fortifications and reinforcing the occupying garrisons in each of these towns was not a priority. The clear and mostly realistic goal of Piyale Pasha to wage a war of conquest in Apulia and Sicily (and later Calabria as well), and a war of decimation everywhere else. Apulia, Sicily, and Calabria were close enough to the empire and its puppet states that they could be easily resupplied by sea, and therefore easily pacified and integrated into proper Ottoman sanjaks - only after such integration could the conquest of Naples and Rome be undertaken with absolute confidence. The activities of Ottoman and Barbary forces elsewhere in Italy and the Mediterranean were for the express purpose of tenderizing the region for future campaigns and to precipitate the collapse of the local Spanish administration, as well as to bloody the nose of Spain and its allies to secure a quick surrender. However, the bombastic initial success of Piyale's campaign on almost every front led his subordinates to encourage him to broaden its scope. With Spanish forces in Calabria abandoning their posts, the viceroy of Sicily still awaiting reinforcements, and the Hispano-Italian relief army at Nola in disarray due to its hasty mobilization, Piyale began to entertain the idea of going straight for Naples and delivering a knockout blow to the Spanish administration in Southern Italy. The possibility of taking Naples - the most populous city on the entire peninsula and in close proximity to Rome - in a 2-year time window was simply too great to resist. With Naples in Turkish hands, Sultan Mehmet himself would be free to lead his armies into Rome in a matter of years, rather than decades. In late 1571, only 8,000 Hispano-Italian troops had so far been assembled at Nola, only 5,000 of which were fully prepared to march, while ships promised by the Republic of Genoa and troops promised by the Papal States were behind schedule.

Juan Pelayo’s Council of War was in a state of hysteria as it scrambled to organize a response and speed up the measures it had been preparing for an Ottoman offensive. It was only in mid 1572 that an armada would be ready to sail from the grand harbor of València. The fruits of years of political centralization under Juan Pelayo and naval reorganization under Álvaro de Bazán were manifest, however: 35 warships from Castile, 22 from Portugal, 15 from València, 15 from Catalonia, and 18 from the many ports of Spanish North Africa were set to be fully operational and outfitted by 1572, while the 30 ships raised by Naples and Sicily would need to stay put for defensive reasons. In all, there were 135 warships, of which 20 were galiots, 72 were galleys, 20 were galleasses, and 23 were galleons. More than 200 independently owned or requisitioned cogs, caravels, and merchant galleys were available to further sustain Spanish naval efforts. Nonetheless, moving the tens of thousands of soldiers needed to confront the Ottoman invasion would be an arduous matter. Sailing directly from Spain to Sicily or Naples was virtually impossible considering the galleys’ need to take on fresh water every few days, and also considering the capricious - and sometimes volatile - nature of Mediterranean weather depending on the time of year. Reinforcing Spanish Italy with Spanish troops would require hopping from Iberia to the Balearic Isles, Sardinia, and the ports of North Africa as needed - a woeful process compared to that of the Ottomans, who could sail directly from Tunis or Albania, and in short time.

Having received news of the barracks of València filling with tercios and the city’s arsenal bustling with activity, Piyale Pasha decided to further complicate the arrival of the Spaniards by authorizing an assault on Sardinia led by Murat Reis, a corsair captain and ambassador to the Kabyle kingdoms of Kuku and Ait Abbas. Just as Müezzinzade Ali Pasha was preparing a march to Palermo, he received orders from Piyale to divert 12 of his galleys and 3,000 of his janissaries, artillerymen, and engineers to back to the port of Biserta in Tunis, and from there they would meet with Murat Reis in Bugia to attack Cagliari. Despite Müezzinzade’s protests that Carlo d'Aragona Tagliavia, the viceroy of Sicily, had arrived in Alcamo and was fast at work fortifying the Gulf of Castellammare along with the valleys of Segesta and Gibellina, 3,000 of Müezzinzade’s crack troops were severed from his campaign and shipped to Murat Reis. By June of 1571, Murat was ready and, accompanied by 4,000 Kabyle auxiliaries, struck at Cagliari with the speed and savagery customary of a corsair like himself, sending Sardinia’s viceroy Juan Coloma y Cardona running all the way to Nuoro to regroup and organize a response. Cagliari became a corsair port overnight, and, along with Bugia, had effectively closed the waters from Cape Serrat to Cape Spartivento. Occhiali meanwhile had begun a campaign along the Calabrian coast after assisting in the capture of Taranto, besieging and taking Crotone, Catanzaro, and Reggio di Calabria by early 1572, while Damat Ibrahim Pasha would lead the forces landed at Gela and Catania to converge on Syracuse. After a bloody, spirited defense, Syracuse fell after 9 weeks, and the beylerbey of Egypt would march northwards to Messina to cut off the city by land while Occhiali descended upon the straits by sea.

- "Et portae inferi..." -

Ottoman advances, 1570-1573

Ottoman advances, 1570-1573

Goaded onwards by their own success, the Italian theater was gradually becoming too large for the Turks. Even with naval supremacy in the Central Mediterranean and the full weight of the imperial war machine at their beck and call, Ottoman forces in Italy were beginning to struggle under the demands imposed by a broad frontline stretching across Apulia, Campania, Calabria, and Sicily. There were never quite enough men to garrison the towns and cities, pacify the countryside, and root out the guerrilla fighters in the hills and mountains, and Piyale Pasha wrote to Konstantiniyye incessantly in search of more conscripts, more janissaries, more galleys and more slaves to man their oars. The clear and straightforward vision of the Italian campaign began to blur as both unexpected difficulties and unexpected opportunities presented themselves, and the different aspirations and opinions of the many strong-willed leaders under Piyale's command began to sow confusion and division in the war effort. In particular, Occhiali and Murat Reis were corsairs through and through - not Ottoman state officials or governors like Piyale, Müezzinzade, or Damat - and ultimately their highest loyalty was to themselves, their private fleets, and the North African harbors they called home. When word reached Piyale of the Spanish relief fleet setting sail from València in April of 1572 (sooner than was expected), he quickly learned the hard way not to place one's trust in a pirate - much less entrust one with an important spearhead position: after being ordered to abandon Cagliari and depart for Sicily to speed up the capture of Palermo and the capitulation of the island, Murat Reis considered affairs in Italy to be secure enough, and had already chosen months prior to instead remain in Sardinia and carve out his own corsair principality (having been denied any such power or authority in the Maghreb).

On the verge of tearing out his beard at the selfish pursuits of one of his most esteemed lieutenants (and chief liaison to many of the Turks' North African allies), Piyale had to choose between ordering Müezzinzade to throw his full strength at Palermo in the hopes of capturing the city or at least cutting it off before the Spanish arrived, or ordering him to hunker down and fortify his position in Western Sicily. Piyale opted for the latter option, deeming it safer, but both options were based on the presumption that Palermo would be the first and most urgent target for relief by the Spaniards. Confusingly, the Spanish fleet moved in short, seemingly erratic spurts, cautiously spending days at a time in a number of harbors in the Balearic Isles and the Maghrebi coast to watch for changes in the wind or the temperament of the sea. The multiple arms of the fleet - moving at different times and anchoring in different harbors - made it difficult for Barbary scout squadrons to ascertain its true size. Most confusingly, the bulk of the fleet then clung close to the North African coast after leaving Algiers, while a smaller portion dithered in the Baleares before suddenly springing directly eastward across open waters, towards Sardinia.

Landing at Oristano ahead of both a massive storm on its tail and a Muslim army moving northwest from Cagliari, five tercios and 2,500 Genoese mercenaries were quickly unloaded and not given a moment's rest before being marched at double time to take the force sent by Murat Reis head-on. While the vast majority of his troops were able to turn on their heels and return to the safety of Cagliari, the sudden arrival and quick movement of 17,500 enemy soldiers sent Murat's defenses into disarray, while the 55 ships that unloaded at Oristano swung around to catch and disperse half of Murat's fleet at Cape Spartivento. Joined by the viceroy and the nearly 4,000 Sardinia militiamen he had mustered, the Spanish army - led by the viceroy of Catalonia and captain-general of Algiers, Luis de Requesens y Zúñiga, and none other than Fernando Álvarez de Toledo, the 3rd Duke of Alba - surrounded Cagliari and dug in. Having had set thousands of slaves to the work or repairing and improving the fortifications of Cagliari immediately after taking the city almost a year prior, Murat was confident in its defenses (and almost rightly so), and was almost certain that this siege would allow Murat to essentially entrap and possibly wear down this large Spanish army, keeping it from intervening in the more important warfare in Sicily and Naples. However, Murat underestimated the sense of urgency that seized the Spaniards, and lacked experience against the heavier warships that now encircled the Golfo di Cagliari. The galleons in particular frustrated the defenders: not very maneuverable compared to the sleek corsair galleys but with very thick hulls and packed to the brim with bronze cannons, able to riddle the harbor with salvo after salvo while unable to be penetrated by anything but the heaviest ordnance. A week and a half into the siege, Requesens - hearing that Spanish marines had landed within the city before a single hole had been punched in the ring wall - repositioned two tercios to stage a direct assault on what was deemed the weakest gate, costing hundreds of lives but forcing open Caglari's outer defenses. Escape by land or sea was impossible for the corsair garrison, and while the defenders fought street-to-street, Murat slit his own throat in the viceregal palace.

The new fleet of All Spain, assembled in force

The other 80 ships of the Spanish fleet trundled onwards along the Kabyle coast, stopping only to bombard the ports of Bugia, Jijel, Collo, Annaba, and Biserta. However, while Müezzinzade girded himself in anticipation, the Spanish Armada did not turn north eastwards towards Sicily. Instead it circled the Gulf of Tunis, establishing beachheads at Radès, La Marsa, and old Carthage in May of 1572. Conscious of the desperate nature of the situation and hoping to inspire his troops on the shores of Tunis and Italian subjects across the Straits of Sicily, Juan Pelayo himself - now approaching 56 years - had joined himself to this fleet and presented himself on the field, having left his eldest (and now only surviving) son Gabriel behind as regent. Alongside his trusted maestre de campo, Julián Romero de Ibarrola, the king of All Spain oversaw the disembarkation of 8 tercios numbering 24,000 men, with 4,000 light cavalry and 14,000 mercenaries, engineers, artillerymen, and priests.

As the Spanish army entrenched themselves around Tunis, Müezzinzade Ali Pasha ordered 25 of his vessels to link up at Nabeul with any ships the nearby Barbary princes could spare. An exhausted relief force ran from Beja and Kairouan, joining nearly 9,000 men at Fouchana, but unexpectedly entered within range of the southern wing of Spanish cannons, who turned away from the walls of Tunis the rain hell on the new arrivals. Struggling to maintain formation under artillery fire - and soon after arquebus fire as well - the cavalry vanguard had no choice but to split down the middle and retreat southwards as the hail of bullets and cannonballs caused their horses to run amok, exposing the foot infantry of this irregular relief army to a shattering charge by the mercenary heavy cavalry of Cosimo de' Medici. With the crippling summer heat endemic to the Maghreb fast approaching, the Turkish fleet - supplemented by another 20 ships - unloaded 4,000 troops on the Cape Bon peninsula and waited out the Spanish. With La Goletta falling to a Spanish assault and with Spanish engineers temporarily securing a tunnel beneath the walls of Tunis, the Turkish fleet chose to round Cape Bon and attempt to draw out a segment of the Spanish fleet into a disadvantageous position. Instead, the Spanish ships stuck close to the harbor of Tunis, and sudden, unseasonal winds pushed hard on the rear of the Turks. With their back to the shore at La Marsa, 15 of the Spanish ships were burned, sunk, or damaged beyond repair, but 18 of their opponents’ galleys were captured alone, with even more sunk or damaged. Tunis would fall only a week and a half after the arrival of the Spanish, and more than 15,000 Christian slaves within the city were liberated. After another week, Ibarrola would turn south to confront the growing army at Cape Bon, inflicting a crushing defeat at Hammamet in late June of 1572. With the nucleus of Islamic naval power in the Mediterranean in his hands, Juan Pelayo decided that Spain - and by extension Christian Europe - could no longer afford to see Tunis change hands with the enemy once again, and allowed his victorious troops to butcher and pillage with abandon. More than 30,000 inhabitants of Tunis were slaughtered, with thousands massacred in the surrounding countryside and by rampaging bands of jinetes throughout Cape Bon. The city and the peninsula were both gutted - among those who escaped death, nearly half were ejected either forcibly or voluntarily.

The tidal wave of blood wafted into the ports of the Sunni world as lurid accounts of monstrous Christians putting innumerable Muslims to the sword filtered in. Upon hearing the news, Müezzinzade Ali Pasha immediately ordered the execution of all 3,000 of his Spanish prisoners, and Piyale Pasha declared that not one more Spaniard would be offered quarter. The Kapudan Pasha withdrew his troops from sieges at Benevento and Campobasso, and began mustering for the march to Naples while Occhiali entered the Tyrrhenian Sea, killing or enslaving nearly all of the inhabitants of the Lipari Islands before carrying out raids on Sorrento, Capri, Castellamare di Stabia, Spineto, and Ischia. In Cagliari, Requesens began coordinating the Neapolitan counteroffensive and 4 tercios and mounted auxiliaries were placed under the command of the Duke of Alba and directed to Sicily, disembarking at Castellammare del Golfo, to the west of Palermo. Juan Pelayo's Sicilian plan was simple: unleash the Iron Duke on Sicily and let him do what he did best. After garrisoning the mostly freshly recruited Tercio de Jaén in Castellammare along with its mounted supplement, Alba took the three "Tercios Viejos" of Murcia, Toledo, and Cartagena and the remaining cavalry with him as he then pushed deep inland and set up shop in Caltanissetta. 9,000 infantry and 1,500 light cavalry was hardly a proper relief force when Ottoman-Barbary forces across the island numbered more than 40,000, but these three tercios had been requested specifically by the Duke of Alba in Cagliari, being filled with some of Castile's most seasoned veterans - some of whom had been serving under Alba for upwards of 20 years. Wasting no time, Alba immediately began ordering the harvest and apportionment of every stalk of grain throughout the island's interior not yet in reach of the Muslims, amassing it in Caltanissetta and a handful of storehouses in the hill country that were unlikely to be found without a map. These were harsh and disruptive measures, but soon the many Berber raiding parties that frequently left the abandoned coast to forage inland were returning empty handed and with their numbers diminished - many were not returning at all. Eventually the armies of Damat and Müezzinzade had to subsist solely on grain shipments from Tunis.

With no choice but to confront the smaller Spanish force, Damat Ibrahim Pasha cautiously marched inland with 22,000 troops to do away with the troublesome Duke of Alba. Finally engaging the Spanish near Enna, Damat engaged his 2,000 janissaries at the front. For the first time, the Spanish tercio and the Ottoman janissary - perhaps the two most fearsome units at the time - met on the field. Unfortunately for Ottoman renown, these particular tercios were commanded by what was also perhaps the most able Spanish commander in history. The janissaries nobly held their line, but were drawn too thin across the valley. With the Turkish sipahis and Berber horsemen cutting themselves to ribbons against the combined arquebus fire and stiff pike defense of the Tercios Viejos, Alba pushed in his reserves in excellent discipline, with not a single tercio square losing formation as it bowled over Damat’s front line. With the Turks trying to withdraw, Alba sprung his surprise: 500 light cavalry and 2,000 Sicilian irregulars descended on the retreating force from the hills to the east and bottled them up against the pursuing tercios. Damat escaped with his personal guard, but the Spanish and Sicilians had killed more than 7,000 while suffering only 2,400 dead, injured, or missing themselves. Losing more of his available soldiery in the following slaughter, confusion, and desertion, Damat limped back to Catania and braced for a Spanish siege. Alba did not have the necessary artillery to break down Turkish defenses, however, and instead continued to rake the Turks out relentlessly over the rough hills of Sicily. Moving to Butera to put pressure on Gela, Alba drew out Müezzinzade’s forces, held off another 14,000 from the rudimentary palisade the Spanish erected. This time another 8,000 Turks were killed or wounded, but the Spanish and Sicilians had endured 3,800 dead and wounded of their own. While his numbers had been bolstered by the local Sicilians (who had taken most of casualties), Alba’s army was now reaching critically low numbers, and had to withdraw back to Caltanissetta. Müezzinzade and Damat, however, could no longer sustain their contiguous control of the southern coast of Sicily, and opted to abandon the poorly defended port of Gela, which Alba then sacked and dismantled its fortifications.

Before the fall of Tunis, unusual circumstances had already begun to jeopardize the Ottoman invasion of Sicily. The Maltese Islands - home to the Hospitaller Knights of St John since the fall of Rhodes - had been raked over in previous years by Turkish corsairs, with a significant portion of their population enslaved each time and their fortifications ground down in bombardments, all to ensure the Knights would not pose a threat to the invasion eventually mounted from the ports of Tunisia. Failure to follow through with the complete seizure of Malta and its Grand Harbor would prove shortsighted, however, as would the Ottoman underestimation of the mettle of the Knights of St. John. Although reduced to a fleet of less than 30 galleys, the Hospitaller navy re-entered the scene in mid 1571 under the leadership of the unwavering Mathurin Romegas, who had made a name for himself as the thorn in the Turkish Sultan’s side in previous decades for his relentless crusading piracy in the Eastern Mediterranean. With a motley armada composed of galleys either purchased on credit in Genoa, seized in battle from corsair captains, or assembled in the Grand Harbor at short notice, Romegas had brought together a potent (albeit small) force in the space of a few months and right under Mehmet III's nose, abetted by the preoccupation with Southern Italy. Swinging forth with characteristic gusto, Romegas sacked Homt Souk on the isle of Djerba and garrisoned the abandoned fortifications, before turning northwards to evade a patrol from Tripoli. Deprived of most of their ships and fighting men, the ports of Sfax, Mahdia, Monastery, and Sousse were left vulnerable to consecutive lightning raids by the Knights of St. John, who also began to intercept supply convoys from Tripoli, Cyrenaica, and Egypt headed for Syracuse. Álvaro de Bazán, at the time gathering forces in Algiers to retake Cagliari, saw the advantage in a predatory fleet operating behind Ottoman lines and preying on its essential grain shipments, and scraped together another 15 galleys to send to Malta to assist in whatever way they could. Long considered a vicious slaver and brigand in the Islamic Mediterranean, Occhiali, Müezzinzade, Damat, and numerous other subordinates petitioned Piyale for permission to pursue Romegas personally and return with his head on a pike. After repulsing the garrison fleet of Tripoli near the Kerkennah Islands, Piyale strongly considered sending as many as 70 galleys to Tunis to smoke out Romegas and torch the Grand Harbor of Malta. However, after the loss of Tunis, the Turks could not divert enough troops to properly challenge the Spanish army in the region, and decided that a favorable truce could only be wrung out of the Spaniards if Naples could be sufficiently threatened, if not taken outright.

Descending on Campania Proper in August of 1572 with an army 33,000 strong, the 12,000 man Hispano-Neapolitan army was forced to give battle at Nola. Not expecting the Ottomans to arrive so soon, the Viceroy of Naples, Iñigo López de Mendoza y Mendoza, pushed the Christian army to hold the line against the bulk of the Ottoman army emerging from the valley extending from Avellino, but was taken by surprise when a 5,000 man janissary division attacked his exposed flank from the north, having emerged from the valley to the south of Caserta. Mendoza and his troops valiantly sustained their defense for nearly 8 hours, but despite endeavoring to fight to the last man, the Ottomans emerged victorious and the viceroy himself was cut down. As only 1,800 survivors poured into Naples after the battle of Nola, the city was now open to siege. However, time was running out for Piyale in more ways than one. As of February 2nd 1572, the Treaty of Zombor - which guaranteed 10 years of peace between the Ottomans and the Habsburgs - had officially expired. After a few months trepidatiously watching the Hungarian border and monitoring the situation in Southern Italy, Philipp II von Habsburg left his brother Johann Karl to handle affairs in Vienna and sent emergency summons to dozens of Christian princes to convene in Bologna. In October of 1572, Philipp II was joined - either in person or represented by emissaries - in Bologna by Emanuele de Avis-Trastamara, the Duke of Calabria and representative of the Spanish Crown, Marcantonio Colonna, the Duke of Tagliacozzo and Duke and Prince of Paliano, Thomas Howard, the Papal Legate to England, Alfonso II d'Este, the Duke of Ferrara, Modena, and Reggio, Francesco Ferdinando d’Ávalos d'Aquino, the marquis of Pescara and marquis of Vasto, Guglielmo Gonzaga, the Duke of Mantua, LMassimiliano II Sforza, the duke of Milan, Carlo de Borgia, the Duke of Romagna and Grand Duke of Tuscany, Francesco Maria II della Rovere, the son of the Duke of Urbino, Filiberto III, the Duke of Savoy, Giacomo Durazzo Grimaldi, the Doge of Genoa, Cardinal Charles de Bourbon, unofficially representing French interests, Alvise I Mocenigo, the Doge of Venice (quite surprisingly), and by Pope Pius V, elected after the death of Pope Pius IV in 1566. After less than 4 days in session, everyone gathered swore themselves unto a Holy League to protect Rome and to drive out the Turkish threat, and pledged whatever resources they were in power to relinquish. The princes of Christendom and their representatives assembled at Bologna were truly fortunate in having a pope like Pius V. Whereas Pope Paul IV had been consumed by his hatred of Spain and Pope Pius IV had been driven primarily by family interests, Pius V was willing to look past petty personal issues and inclinations of Italian patriotism. As a Dominican, Pius V was a pope with a monastic background - a rarity - and the intense spirituality and asceticism of his Dominican origins were manifest in the strength of his convictions and his unbending devotion to uniting the Catholic cause. Long known as a firebrand against political and fiscal corruption in Rome, Pope Pius V used his new authority and flung open the papal coffers, offering all funds available to the Holy League. With the Ottoman front unraveling in Sicily and developing in their favor at Naples, the conclusion of the Italian war remained completely unsure, and the hour of the fever pitch climax of this conflict - centuries in the making - was soon at hand.

Banner of the Holy League

Last edited:

I wanted to add that I took a bit of inspiration for this update from @Zulfurium and his TL "Their Cross To Bear"

Oh man, what an absolutely fantastic birthday gift, to have an update on your favourite timeline!!

Keep it up, man. The wait is painful but always 100% worth it.

Also... I tend to root for the Christians in every TL but I must admit that this entire paragraph was really hype.

Keep it up, man. The wait is painful but always 100% worth it.

Also... I tend to root for the Christians in every TL but I must admit that this entire paragraph was really hype.

This quote about the Duke of Alba too.Every raw resource and industrial infrastructure available to the Ottoman State had been vigorously utilized for nearly 8 years to prepare a mass invasion. Galleys, galiots, and troop ships had been endlessly assembled at the arsenals of Konstantiniyye, Alexandria, Tunis, and Tripoli, their oars manned with slaves from Ruthenia, Greece, Hungary, Croatia, Spain, the Caucasus, and, most importantly, Sicily and Naples. Iron, timber, and pitch from the Balkans, textiles and grain from Egypt and Tunisia, navigators and experienced seamen from the Maghreb and the Aegean Isles, horses, mules, and camels from Anatolia, Hejaz, and the Levant - all poured in to the ports, foundries, and rallying fields to fuel and equip the Ottoman war machine. Countless manpower from every corner was called upon or volunteered themselves - elite janissaries, Tatar horse archers, Syrian ghazis, Slavic irregulars, Turkish conscripts, and more - and spent months or even years trekking across the mountains and valleys of the Near East and the Balkan Peninsula to muster at the ports of the empire. Upon setting sail, these fleets and their supply convoys numbered nearly 500 ships in total. Apart from their human cargo, they carried millions of yards of cloth, canvas, and parchment, hundreds of thousands of iron ingots, arrows, arquebus balls, millet bread biscuits, and barrels of pitch, tens of thousands of tents, beasts of burden, battleaxes, scimitars, spears, firearms, and hundreds of roaring cannons to pulverize the Turkish army’s way through the Italian Peninsula.

Juan Pelayo's Sicilian plan was simple: unleash the Iron Duke on Sicily and let him do what he did best

You cram more work and material into one update than I do in twenty. While it is inconvenient to wait five to six months for an update, it certainly is worth it when it comes. Keep up the great work, @Torbald.

Threadmarks

View all 48 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

38. Ventos Divinos 39. The Great Turkish War - Part I: El Reino de África 40. The Great Turkish War - Part II: The One-Eyed Sultan 41. The Great Turkish War - Part III: Blood in the White Sea 42. The Great Turkish War - Part IV: Rûm 43. The Great Turkish War - Part V: Otranto 44. The Middle Sea Transformed 45. Ilhas de Ofir

Share: